Abstract

Trust is an essential component of successful cooperative endeavours. The global health response to the 2014–2016 West Africa Ebola outbreak confronted historically tenuous regional relationships of trust. Challenging sociopolitical contexts and initially inappropriate communication strategies impeded trustworthy relationships between communities and responders during the epidemic. Social scientists affiliated with the Ebola 100-Institut Pasteur project interviewed approximately 160 local, national and international responders holding a wide variety of roles during the epidemic. Focusing on responder’s experiences of communities’ trust during the epidemic, this qualitative study identifies and explores social techniques for effective emergency response. The response required individuals with diverse knowledges and experiences. Responders’ included on-the-ground social mobilisers, health workers and clinicians, government officials, ambulance drivers, contact tracers and many more. We find that trust was fostered through open, transparent and reflexive communication that was adaptive and accountable to community-led response efforts and to real-time priorities. We expand on these findings to identify ‘technologies of trust’ that can be used to promote actively legitimate trustworthy relationships. Responders engaged the social technologies of openness (a willingness and genuine effort to incorporate multiple perspectives), reflexivity (flexibly responsive to context and ongoing dialogue) and accountability (taking responsibility for local contexts and consequences) to facilitate relations of trust. Technologies of trust contribute to the development of a framework of practical techniques to improve the acceptance and effectiveness of future emergency response strategies

Keywords: qualitative study, health policy, prevention strategies, viral haemorrhagic fevers, health services research

Key questions.

What is already known?

Rumours, suspicions and mistrust during the 2014–2016 West Africa Ebola outbreak challenged effective emergency response.

What are the new findings?

Practical ways to address mistrust during the West African Ebola outbreak.

Trustworthiness between communities and responders was achieved through openness, reflexivity and accountability.

These three social technologies of trust, adapted to real-time on-the-ground priorities, operating in tandem to foster trust.

What do the new findings imply?

Recognising and engaging technologies of trust, such as openness, reflexivity and accountability, can strengthen effectiveness of emergency response.

We propose a framework for social technologies of trust for future epidemic response strategies.

Introduction: Trust as a social technology

The 2014–2016 West Africa Ebola outbreak remains the deadliest to date, killing more than 11 300 people in Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia.1 Response efforts challenged already tenuous regional relationships of trust, amplified by both the geographic distance and long-standing social distance between affected rural communities and those developing official response recommendations in urban areas.2–4

Amid fear and uncertainty, and with a reported case fatality rate of 70%,5 local, national and international responders dropped everything to assist in the epidemic. From a wide range of backgrounds and experience, ‘responders’ included social mobilisers, doctors, nurses, scientists, psychosocial counsellors, government officials, epidemiologists, health workers, ambulance drivers, burial teams, anthropologists and more.

Responders arrived on the ground to scarce resources and historically rooted political instabilities that strained their best efforts. Communities questioned the trustworthiness of government messaging surrounding Ebola transmission.6–10 Healthcare workers themselves lost trust in the safety of their workplace as coworkers died.6 Active distrust flourished as contradictions between public health messages and what was observed multiplied.9

Responders navigated a complex web of mistrust between lay people and health professionals, and among all affected by the outbreak.6 9 Trustworthy communication was challenged by complex competing explanatory models of official responders and community members.6 Biomedical explanations to change behaviour were often neither contextually appropriate nor effective. Instead, they served to divide those developing standardised response protocols from those expected to follow them.11 Prioritising ‘people’s trust in the information source, mode of communication, and consistency of messages’ for acceptance of public health messages was recommended.12 Moreover, strategies that involved listening to and engaging communities and incorporating their suggestions proved more fruitful than externally formulated approaches.6

Difficulties in establishing and maintaining trusting relationships during the response pivot on the inextricable influence of sociopolitical and colonial histories.2–4 6 Comparing experiences of social resistance in Sierra Leone and Guinea, Wilkinson and Fairhead emphasise the importance of assessing these political-trust configurations when planning response interventions.13 Citizens in all three countries were sceptical of official response efforts, especially interventions spearheaded by their national governments.7

Rampant rumours throughout the outbreak reflected the politicised nature of resistance, filling gaps when details were withheld or unclear.13 A history of posting outsiders to Guinea’s remote forest region contributed to rumours of Ebola’s appearance as intentional ethnocide.6 Indeed, sending outsiders to the forest region met overt resistance, most infamously the murder of several health workers in Womey.6

Unpacking these structural inequalities helps in understanding the ‘symbolism of the messenger’ and to identifying allies who are trusted by a wide variety of community members.13 Several scholars emphasise the influence of religious leaders,14–16 though caution against a purely prescriptive notion of trusted individuals:

In no setting can leaders or fault lines be assumed. Instead historically and anthropologically informed enquiries, which proved successful even in the most troubled parts of Guinea, need to be conducted to identify salient local politics before intervening, and with interventions proceeding with these sensitivities in mind.13

As the outbreak continued, global health leaders came to recognise that epidemic response requires a combination of strategies beyond the biomedical.17 18 Even routine interventions such as vaccine delivery require strategies that earn people’s legitimate trust through commitments with local communities knowledgeable of on-the-ground realities and emerging events.19

Trust plays a central role in all human relationships,20–26 reinforcing accountability and acting as a ‘social glue’.24 Without some level of trust, ‘everyday activities…would be very challenging’.22 Onora O’Neill describes this active engagement of individuals wanting to place trust ‘where it is deserved’ as ‘trustworthiness’.27 Trustworthiness, then, requires some evidence of honesty and reliability in a given claim. What makes the messenger worthy of trust?

During the Ebola crisis, what practices made some relationships more genuinely trustworthy than others?28 What techniques worked to create an avenue for effective emergency response?

In the early part of the 20th century Marcel Mauss defined technology as the dedicated study of techniques.29 Focusing on the social nature of technology rather than the term’s mechanistic connotations, for Mauss techniques are situated in the social realm as ‘tactic[s] for living, thinking, and striving in common; they are above all a means and medium for the production and reproduction of social life’.30 Techniques presuppose and generate knowledge; the practical enactment of a technique encompasses continual learning and adapting.31

Michel de Certeau expanded on the tactical application of social technologies as calculated actions in everyday social life. Distinguished from tactics, strategies are typically seen as tools for elites while tactics can be carried out by those outside of powerful loci. Locals and nationals operating within hegemonic colonial regimes, for example, might tactically position themselves to make use of ‘chance offerings of the moment’.32

Drawing on Mauss and de Certeau, the empirical evidence from anthropologists in the field during the crisis, and semistructured qualitative interviews with demographically diverse responders involved in the West Africa Ebola outbreak, we explore observable techniques that were performed by responders to generate trustworthy relationships. We identify and examine what made some relationships more genuinely trustworthy than others in data collected for the Ebola 100-Institut Pasteur (E100-IP) project, an initiative to collect and archive narratives of the West Africa Ebola epidemic. Our findings demonstrate that responders performed a variety of techniques that implemented trustworthiness on the ground during the West Africa response. From this empirical evidence, we propose a framework for social technologies of trust that may be incorporated into future epidemic response strategies.

Methods

This article draws on in-depth qualitative secondary analysis of interviews conducted as part of the E100-IP project. Informed by medical anthropology theory and methodologies, the project aimed to formally document responder experiences and make these data permanently available for researchers, policymakers and other interested parties in a free, open-access, online archive (Abramowitz, in submission).33

Thirty-two social scientists conducted 159 hour-long interviews with responders to the West Africa Ebola epidemic between May 2015 and June 2016 (Abramowitz, in submission). Approximately 100 E100 interviews with a diverse range of humanitarian and biomedical responders were collected by volunteers, and another 59 interviews focusing exclusively on biomedical responders sponsored by IP were conducted by two anthropologists. All interviewers had previous qualitative research experience and underwent a standardised training process to ensure data collection occurred within a consistent ethical and procedural framework. A flexible and adaptive interview structure was developed to accommodate the geographically and socially diverse responders. These open-ended interview frames allowed interviewers to pursue each responder’s unique narratives and experiences as they arose, providing insights into the complex sociopolitical dynamics of the outbreak.

Participants were recruited through snowball sampling, starting from E100-IP researchers’ familiarity with those involved in the response and of attendees at several international conferences. The interviews were not translated or cleaned prior to transcription. Ethics review took place in North America, Europe and West Africa according to the affiliations of those involved. All interviews met the Tri-Council Policy Statement 2 definition of minimal risk for informed consent and research activities.34

We received E100-IP interview data on transcription and final confirmation of informed consent. Between May and November 2017, seventy-one transcripts in total became available: 36 collected through E100, and 35 collected through IP. Using NVivo V.12 qualitative analysis software, we thematically coded data on arrival for the experiences and decision-making processes of responders (eg, first encounter with Ebola, trusted sources of information during the response, impression of lay populations and other responders). The themes from this analysis informed the coding of the E100 sample (n=36); any themes initially missed were inductively coded during second review.

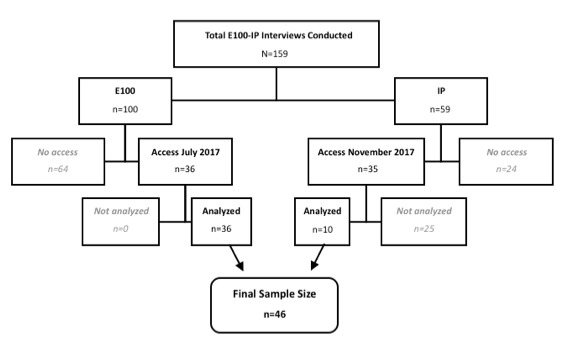

No new themes appeared after the 33rd E100 interview. Of the E100 sample, most responders were posted to one country (Sierra Leone, 14; Liberia, 11; Guinea, 3), 6 worked in more than one country and 2 worked in all three. Rather than coding the entirety of the IP sample on its arrival in November 2017, we instead aimed for demographic variability. Since the E100 interviews featured few responders to Guinea (5), we purposively sampled the IP interviews (n=35) for responders in Guinea (n=10), resulting in a final sample of 46 interviews (figure 1). Thirty-seven of these interviews were conducted in English, eight in French and one in German.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of sample sources from Ebola 100-Institut Pasteur (E100-IP) data set.

This analysis produced 185 thematic codes which were explored along several comparative axes including the responder’s country of involvement, type of response role and permanent residence (international, national or local) to identify consistencies and contrasts with the overall coding frequency. These results were synthesised into nine broad emergent themes (Box 1). This article focuses on the emergent theme of ‘trust/mistrust’ which was empirically based on the patterns in all data co-coded with ‘mistrust’, ‘trusted voice’ or ‘trusted source of information’ (online supplementary file).

Box 1. Emergent themes.

Navigating social and geographic landscapes.

Community engagement.

Emotional context.

Expertise/knowledge.

Responding from the ground up.

Dialogic response efforts.

Trust/mistrust.

Intranational tension.

Conducting clinical trial research in a response setting.

bmjgh-2018-001272supp001.pdf (103KB, pdf)

Interviewee demographics are listed in table 1. Below, we denote the participant’s permanent residence (international, national, local), organisational response role and country in which they worked. We categorised response roles as follows:

Table 1.

Interviewee identifiers and demographic overview

| Permanent residence (n) | Organisation type (n) | Country of response (n) |

| International (28) | Humanitarian aid (15) | Guinea (3) |

| Liberia (1) | ||

| Sierra Leone (1) | ||

| Sierra Leone and Guinea (1) | ||

| Sierra Leone and Liberia (2) | ||

| Confidential* (7) | ||

| Healthcare and biomedical (6) | Liberia (1) | |

| Sierra Leone (2) | ||

| Confidential (3) | ||

| International institution (4) | Liberia (1) | |

| Sierra Leone (1) | ||

| Sierra Leone, Guinea, Liberia (1) | ||

| Confidential (1) | ||

| Small-scale organisations (2) | Sierra Leone (1) | |

| Confidential (1) | ||

| Government (1) | Confidential (1) | |

| Local (10) | Psychosocial support (5) | Liberia (2) |

| Sierra Leone (2) | ||

| Confidential (1) | ||

| Humanitarian aid (3) | Confidential (3) | |

| Small-scale organisations (2) | Liberia (1) | |

| Confidential (1) | ||

| National (8) | Government (4) | Guinea (1) |

| Confidential (3) | ||

| Humanitarian aid (2) | Confidential (2) | |

| Healthcare and biomedical (2) | Guinea (1) | |

| Confidential (1) |

*Responders requested confidentiality.

Humanitarian aid (n=20), for example, WHO, UNICEF and other United Nations agencies.

Healthcare and biomedical response (n=8), for example, Médicins Sans Frontières clinicians, clinical trial scientists and other formal health-related roles.

Government (n=5), for example, health ministers, those involved in official national response efforts.

Psychosocial support (n=5), for example, counsellors and directors of psychosocial organisations.

International institution (n=4), for example, those primarily affiliated with an academic institution rather than a non-governmental organisation (NGO).

Small-scale organisations (n=4), for example, organisations with less than 100 personnel.

Results

Our results centre on responders’ experiences building genuine trustworthy relationships. Trustworthiness was achieved through social techniques (conscious and unconscious tactics) of working closely and transparently with communities to develop what we call here ‘social technologies of trust’ that focused on principles and practices of openness, reflexivity and accountability.

Openness

In considering public participation in the regulation of health technologies, Graham and Jones define openness as engagement with and a willingness to incorporate multiple perspectives.35 In this sense, openness becomes an orientation towards collaboration that is ‘two-way, where information flows in multiple directions through engaged exchange and discussion’35 (p 341).

In our data, engaging openness as a social technology proved to be a key component of trustworthy relationships. For example, a Guinean government researcher valued the relative transparency of one particular clinical study team, appreciating that ‘all the documents were on my desk in front of me’ to work with and comment on. These actions resulted in a relationship of ongoing exchange and interaction, where the researcher and clinical trial investigator developed a friendship, borrowed belongings and discussed study proceedings freely.

Openness also played out between Ebola patients’ families and staff at Ebola treatment centres (ETC). After their initial failure to dispel rumours about stolen family members whose bodies, blood and bones were being sold in Europe, along with other violent misunderstandings circulating at the time,6 some ETCs installed plastic sheeting to reassure families and patients and allow them to see one another (International humanitarian responder). Further, healthcare providers began fostering trust, countering existing suspicions by engaging families in the Ebola diagnostic process:

I would just basically walk [families] through the first assay and then the second one and show them the visual results. And when you see this curve, that either stays flat or is negative, or goes up and is positive, or you would see the wells after the ELISA which are bright green if it’s positive or blank when it’s negative. They really started to believe, and they trusted us because we were completely open and honest about what we were seeing. [emphasis added] (International virologist in Sierra Leone)

Some ETCs encouraged staff to go into communities to interact and establish relationships with their patients’ families, cultivating an ongoing open exchange:

We’d take photographs of the patient, if they were well enough…say ‘This is where they are, this is what they’ve got, we’re waiting for the results’…if the families weren’t in quarantine…then we would encourage them to come spend as much time as they wanted in the ETC…[we also] give them our hotline telephone number and they could phone in at any time…through the progress of the patient, keep them up to date with what’s happening. (International nurse)

Since there are value decisions surrounding what will be made open, how, by and for whom, openness demands constant ‘articulations of what is valuable and what relationships exist to generate, ensure and reinforce such value’.36 37 We caution then that techniques of openness are neither inherently positive nor negative. Openness can, however, create avenues for establishing trustworthy relationships in an epidemic context, especially when found in tandem with accountability and reflexivity.35 In the case of the West African Ebola response, our findings indicate that openness was particularly valued when its application was relevant, socially contextualised and adaptive to the continually changing nature of epidemic response needs. Consequently, openness often orbited and intersected with reflexivity.

Reflexivity

Reflexivity provides a space for creating and sustaining a dialogue between those with conflicting knowledge systems. In this space, a plurality of potential standpoints and explanatory models can be recognised and encouraged to coexist.35 From this analytic perspective, reflexivity is conveyed, ‘not through a predetermined kit of approaches from which they can draw ‘the perfect tool’, but rather, by assessing each case according to the best way to deal with its particularities’.35

Trustworthy response efforts address these ‘particularities’. In Liberia, one international institution found a way to bridge the disconnect between official response policies and the priorities of those affected by adapting community toolkits originally designed for HIV prevention to accommodate the Ebola outbreak:

[It became] very clear that Ebola was not the primary issue in most of these communities. So we had to then, as we’re going through the training, modify and adapt and give people a much more flexible version, you know like, ‘Here’s the Ebola Facilitator’s Guide, but actually you’re probably gonna want to talk about other issues like routine immunization or you know, malaria, or whatever.’ So creating a… partner guide that enabled the facilitators [to address] whatever worthy identified needs [arose] in the community. (International academic with experience in Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea)

Other responders exhibited reflexivity by shifting their communication strategies from top-down to bottom-up, adopting reciprocal approaches that established and respectfully encouraged constant feedback from people on the ground in affected communities. Rather than providing a standardised message, an international medical responder working in Sierra Leone recalled the importance of engaging local leaders in conversation:

I think that they were really listening, and they wanted to know what can we do to prevent it and how can we incorporate the advices that I gave into their daily life…of course many things that can be difficult when you have these cultural differences, so when I told them that they should avoid touching other people then there was one of the chiefs asking, ‘What do I do then when I have,’ I don’t know how many it was, ‘8 wives and they all wanted to be satisfied?’ so it was really for me, also, an eye opener. (International physician working in Sierra Leone)

In return, this physician addressed the leaders’ questions and concerns and provided tools, such as photos of the virus itself, to complement biomedical descriptions of Ebola to communities in their own words. She emphasised that ‘these two hour meetings with the community made a bigger impact than the work I did at the hospital,’ describing their improved communication as a product of increased ‘understanding of each other’.

Effective solutions often involved looking beyond standardised recommendations and reflexively engaged affected individuals in an ongoing exchange of information and experiences:

Everything we learned during the Ebola response we learned in the field, in the face of death and crisis. The messages you see were created, crossed-out, taken up, and tested in the field. If it didn’t work, we’d re-examine and move forward [with a better solution]. (National government laboratory technician)

This sentiment was echoed by an international responder’s encounter with a Sierra Leonean-led ETC that found ways to maintain a safe touch policy despite official recommendations to avoid touch between all individuals. The medical and interpersonal success of this choice demonstrates the importance of reflexivity to responding to priorities on the ground. Lack of touch was extremely isolating for staff and patients in an already intense environment. The relationships between all involved benefitted from the ETC’s commitment to care.

The common perception expressed by a local humanitarian responder that everything was ‘learned by doing’ reinforced the notion that learning happens best in practice, on the ground, rather than in far-off international boardrooms. Constantly restrategising messages with direct feedback and input from communities was vital. In fact, communication was more effective once ‘we started visiting the people, going into the community, getting people to lead the fight themselves’ (Local humanitarian responder).

Accountability

Accountability involves ‘accepting responsibility for the consequences of decisions’35 (p 339). According to an international humanitarian responder, this technology to establish trust necessitates a ‘feedback loop’ between all potential actors to facilitate their plural needs being addressed. When formal response strategies, such as contact tracing or resource distribution, failed to include local knowledge38 or were deemed untrustworthy, our data show responders often actively took intervention on as their responsibility, they felt and acted on a responsibility to respond using local advice in a timely way to address emergent priorities on the ground.

For example, two responders, a national social anthropologist and an international virologist, were concerned that food was not being properly delivered by the responsible parties. The national responder suspected corruption of the ‘middle man’ in the food delivery chain:

When the response first broke out, one [of] the hardest hit areas was my hometown…at that time it was really chaotic. People were going for days without food under quarantine. And I remember…the quarantine manager saying you know, they are raising the funds from [city] and I’m thinking ‘well how is that possible when they have just given money to the people to help out?’ So I then started buying food out of my own pockets using my own money and delivering this food directly to the quarantine homes. Because I was concerned using the middle man that’s why the food wasn’t getting to the people because there was a lot of rumours about people diverting the food for their own use. (National social anthropologist working for a humanitarian organisation)

Demonstrating accountability to her hometown, this responder removed the ‘middle man’ and took responsibility for food delivery, ensuring the needs of those in quarantine were met.

The international virologist also began a food delivery service, although with a slightly different motivation. Rather than corruption, this responder was frustrated with the poor prioritisation of needs on the ground by those distributing resources from the city centres:

[City 1] was focusing on small non-essential things. What shocked me was maybe the hours of conversation they had about hand sanitizer…well, we need ambulances, we need doctors, we need medicine, we need fuel to make the generators run…We need like, y’know, food for the patients! I had to call my expat friends in [City 2] that, starting tonight, we don’t have any food to feed 30 patients in [City 2] and 30 patients in [City 3]! That was early/mid-June [2014] …they got together and they gave 1000 euros and they set up like a couple of cooks, and we started giving all these patients daily free meals! Just a couple of expat kids, right. And then after three weeks, oh! Well suddenly [International Organization] came in. Which was great and amazing…but why in the hell did it take that long? And why did [International Organization] come in because of a couple of emails that I sent to [City 1]—like how on earth were they not requisitioned immediately by the [City 1] National Task Force meetings. (International virologist in Sierra Leone)

Thus, when formal strategies were disconnected from priorities on the ground, ‘just a couple of expat kids’ stepped up and made themselves accountable to ensure their community’s needs were adequately met. Similar circumstances sparked a community initiative run entirely by volunteers who provided care for Ebola orphans and ensured they could still go to school (Local programme manager for a religious humanitarian organisation). Other examples of such techniques included communities screening themselves for Ebola and sending their children to volunteer for Ebola hotlines (International director of a humanitarian organisation; National social anthropologist for a humanitarian organisation; International virologist in Sierra Leone).

Moving beyond acts of accepting or taking responsibility, responders demonstrated that techniques of accountability prioritise long-term commitments and community care. For instance, engaging as a member of the community and interacting on a day-to-day basis outside of the context of the ETC or vaccine trial influenced perceived levels of trustworthiness (National Guinean regional response coordinator). Trustworthiness of these microlevel day-to-day interactions has long been recognised in religious communities:

Religious structures, especially in that affected area, still are given much credibility and respect. The messages we were able to pass through our community mobilization and education efforts were heard and accepted because they also saw the other kinds of caring work that was being done by the church. [emphasis added] (International director of a religious humanitarian organisation working in Sierra Leone and Liberia)

Expanding on our notion of accountability, caring relationships are important components of trust in secular response. For instance, a Liberian responder working for a local women’s group described the importance of consistency and investment in the community’s well-being as key to the community’s trust in the group: ‘currently we were there for them, after the quarantine we also are there for them. So, they trust us’. An international nurse valued the cohesiveness of a locally staffed ETC. She contrasted this to an ETC staffed by a team of international volunteers, who ‘would come and do six to eight weeks, but they weren’t a team’. These responders emphasised the importance of being accountable beyond Ebola—by focusing primarily on providing care, rather than on providing interventions, their messages were more likely to be accepted.

People took responsibility for others and became accountable through caring for one another, regardless of previous formal training:

…people were utterly dying, because healthcare was so scarce…half of us were afraid to touch them…Most hospitals were closed, so they brought in something they called a home care, that is, you go take care of Ebola patients or any other sickness…I really enjoyed that part, where people would care for their sick relatives with health care and try and conquer a disease…, it’s really effective because everybody started doing it, even if you are not a healthcare professional, once you do it, learn it, you can take care of people. The lady who brought that idea, she took care of more than twenty patients with Ebola, and she was not even a [healthcare] professional…she was a social worker. [emphasis added] (Local research assistant for a humanitarian organisation)

A Liberian women’s group led a similar initiative called ‘room care’ that involved training women to take care of their family members at home during the peak of the outbreak. A local woman working for this group regarded room care as their most effective effort as trainees shared their knowledge, leading to an increase in hand washing in the wider community.

Similarly, training people to perform safe burials promoted feelings of cohesiveness and trust when these communal rituals helped to ‘get rid of their tragic memories and ease pain…by restoring peace in the community’ (Local executive director of a Sierra Leonean psychosocial organisation).

Trustworthy, meaningful contributions to epidemic response came from a wide variety of actors; accountable response took many forms, including commitment to training and training the trainers, and being willing to care for those in need.

Discussion

Our focus on technologies of trust provides a platform to reframe perceptions of both the intentions and abilities of emergency response, thereby improving the level of trust in the intervention. These technologies are not mutually exclusive; openness, reflexivity and accountability achieve legitimacy together as a constellation employed fluidly in what Bijker and colleagues call ‘trust in tandem’.20

Through examination of a plurality of social technologies and their interplay, we highlight Mauss’ holistic observation of ‘how techniques, objects, and activities function together in a manner that is both efficient and meaningful’.29 They exist in constant, fluid exchange and are oriented towards building relationships, not one-off encounters. This requires a level of investment and genuine interest in encouraging relationships, to which responders at all levels need to be held accountable.

The added value of a diversity of techniques proposed by Mauss39 (p 52) is demonstrated by the multiple tactics carried out by Ebola responders to form trustworthy relationships. Nevertheless, during the epidemic some techniques proved more appropriate and effective than others. Responders benefited from orienting towards more trustworthy relationships incorporating these technologies: openness, reflexivity and accountability.

With the everyday uncertainties of Ebola - where even powerful elites found themselves in unfamiliar situations with limited resources - previous strategies, such as those for food distribution, proved ineffective. Instead, successful response involved flexibly employing techniques on the ground: a social capacity to tactically adapt to ever-changing circumstances,32 and a commitment to care that extended beyond the emergency context.40

The technologies of trust demonstrated here provide empirical evidence for trustworthiness that was lacking in the disconnected, one-size-fits-all messaging that failed to account for the complex realities and priorities experienced locally. For instance, the openness shown by some responders, their reflexive engagement in communities and accountability for more compassionate and social-contextualised engagement provided tangible justification that their messages, institutions and interventions could be trusted. Those who acted in ways that were non-transparent, non-reflexive or lacked accountability were not considered trustworthy. Technologies of trust are the tools for a logic of care that involves a multiplicity of actors sharing the work of ‘persistent tinkering in a world full of complex ambivalence and shifting tensions’40 (p 14).

Since technologies both require and create knowledge,41 previous studies of the importance of cultural context and meaningful community engagement are necessary to situate these technologies of trust. In practice, successful technologies of trust are implemented with careful consideration of the current context and a willingness to engage widely and adapt with the ever-evolving nature of an emergency response.

We caution that this should not be interpreted as a singularly hopeful orientation. Barriers to trust could likewise be conceptually developed as techniques of mistrust (eg, interventions inconsistent with practical needs and concerns). Articulating what has failed in the past, however, is only useful if mistakes are not repeated. It does not inherently provide any direction of what will work in the future. By conceptualising the technologies that facilitate trust, we can better articulate their practical importance into policy recommendations on a macroscale and foster face-to-face microinteractions that are empathetic, relevant and well received.

There are limitations to this study. The E100 interviewers were a diverse group of graduate students, junior, senior and emeritus faculty, and NGO workers who were available and willing to engage in this project. Thus, interviewers had varying levels of experience which affected the quality of probing, ability to follow-up and the depth of the interview. Our secondary analysis of other researcher’s interviews distanced us from the actual context. The interview guides were deliberately broad. Trustworthiness was not directly addressed in the interview guide but rather emerged from the interview data. Nonetheless, we suggest that valuable generalisations can be made from these data about the importance of trusting relationships in emergency health response.

Conclusion

Our study documents the role of trust in establishing effective relationships in epidemic response that emerged from a qualitative analysis of 46 interviews with local, national and international responders in Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia to the West African Ebola outbreak. Elucidating the tactical techniques that facilitated active trust on the ground helped identify overarching technologies of trust that can be employed strategically in the long term.

As we write, the Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo has killed more than 290 people and proves difficult to contain with violent attacks at sites of intervention.42 In some communities, ‘the disease can seem less frightening than these other, long-standing threats’.43 Fear and a general mistrust of both the health system and outsiders lead Congolese Ebola sufferers to withhold from sharing their contacts with responders. These tensions directly hinder response efforts as more than two-thirds of Ebola cases continue to appear outside known transmission chains.43 Controlling the recent outbreak in the eastern Congo perhaps poses an even greater threat than occurred, for example, in Womey, with rumours igniting distrust, exacerbated by organised militant groups.44 45 We propose our framework for genuine engagement involving technologies of trust that embraces the principles and practices of openness, reflexivity and accountability to provide a useful tool for both understanding and improving future epidemic response.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Stephanie M Topp

Contributors: MJR and JEG conceived the study, carried out the analysis and wrote the first draft. TGV contributed to the analysis and writing.

Funding: This research was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Grant PJT-148908, Global Vaccine Logics, and would not have been possible without the dedicated work of the Ebola 100 volunteers who contributed to the interviews collected as part of the Ebola 100-Institut Pasteur project, established by Dr Sharon Abramowitz and TGV. The Institut Pasteur project received support from the Institut Pasteur Ebola Task Force.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Centre for Disease Control and Infections Years of Ebola virus disease outbreaks. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/history/chronology.html [Accessed Jun 2018].

- 2. Goguen A, Bolten C. Ebola through a glass, darkly: ways of knowing the state and each other. Anthropol Q 2017;90:423–49. 10.1353/anq.2017.0025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Faye SL. L’‘exceptionnalité’ d’Ebola et les ‘réticences’ populaires en Guinée-Conakry. Réflexions partir d’une approche d’anthropologie symétrique [The ‘Exceptionality’ of Ebola and Popular ‘Reticence’ in Guinea-Conakry. Reflections from a Symmetrical Anthropology Approach]. Anthropologie & Santé 2015;11. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lamboray JL, Sherlaw W. Ebola, question de confiance [Ebola, a matter of trust]. Santé Publique 2016;28:123–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. WHO Ebola Response Team, Aylward B, Barboza P, et al. . Ebola virus disease in West Africa--the first 9 months of the epidemic and forward projections. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1481–95. 10.1056/NEJMoa1411100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Anoko JN, 2014. Communication with rebellious communities during an outbreak of Ebola virus disease in Guinea: an anthropological approach. Available: https://www.acaps.org/sites/acaps/files/key-documents/files/anoko_communication_with_rebellious_communities_during_an_outbreak.pdf [Accessed Jul 2018].

- 7. Chandler C, Fairhead J, Kelly A, et al. . Ebola: limitations of correcting misinformation. The Lancet 2015;385:1275–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62382-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ozawa S, Stack ML. Public trust and vaccine acceptance--international perspectives. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2013;9:1774–8. 10.4161/hv.24961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Blair RA, Morse BS, Tsai LL. Public health and public trust: survey evidence from the Ebola virus disease epidemic in Liberia. Soc Sci Med 2017;172:89–97. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lori JR, Munro-Kramer ML, Shifman J, et al. . Patient satisfaction with maternity waiting homes in Liberia: a case study during the Ebola outbreak. J Midwifery Womens Health 2017;62:163–71. 10.1111/jmwh.12600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schroven A, 2016. How can the health systems of Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia be improved? open space conferences report. Available: http://health.bmz.de/events/News/Guineas_Liberias_and_Sierra_Leones_health_systems/OpenSpaceConferences_GN-LR-SL_2016_e.pdf [Accessed May 2018].

- 12. Schwerdtle P, De Clerck V, Plummer V. Survivors' perceptions of public health messages during an Ebola crisis in Liberia and Sierra Leone: an exploratory study. Nurs Health Sci 2017;19:492–7. 10.1111/nhs.12372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wilkinson A, Fairhead J. Comparison of social resistance to Ebola response in Sierra Leone and guinea suggests explanations lie in political configurations not culture. Crit Public Health 2017;27:14–27. 10.1080/09581596.2016.1252034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jalloh MF, Bunnell R, Robinson S, et al. . Assessments of Ebola knowledge, attitudes and practices in Forécariah, Guinea and Kambia, Sierra Leone, July–August 2015. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2017;372 10.1098/rstb.2016.0304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Marshall K. Roles of religious actors in the West African Ebola response. Dev Pract 2017;27:622–33. 10.1080/09614524.2017.1327573 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Peiffer-Smadja N, Ouedraogo R, D'Ortenzio E, et al. . Vaccination and blood sampling acceptability during Ramadan fasting month: a cross-sectional study in Conakry, guinea. Vaccine 2017;35:2569–74. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.03.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ross AG, The BMJ Opinion , 2017. Vaccination alone will not halt the next global pandemic. Available: http://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2017/06/09/allen-ross-vaccination-alone-will-not-halt-the-next-global-pandemic/ [Accessed Jun 2018]. 10.1136/bmj.j2864 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18. WHO Social science: Revolutionizing emergency response. Available: http://www.who.int/risk-communication/social-science-interventions/en/ [Accessed Jun 2018].

- 19. Graham JE, Lees S, Le Marcis F, et al. . Prepared for the ‘unexpected’? Lessons from the 2014–2016 Ebola epidemic in West Africa on integrating emergent theory designs into outbreak response. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3:e000990–3. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bijker EM, Sauerwein RW, Bijker WE. Controlled human malaria infection trials: how tandems of trust and control construct scientific knowledge. Soc Stud Sci 2016;46:56–86. 10.1177/0306312715619784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Collins HM. Gravity’s Shadow: The Search for Gravitational Waves. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dingemans E, Van Ingen E. Does religion breed trust? A cross-national study of the effects of religious involvement, religious faith, and religious context on social trust. J Sci Study Relig 2015;54:739–55. 10.1111/jssr.12217 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Earle TC. Trust in risk management: a model-based review of empirical research. Risk Anal 2010;30:541–74. 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2010.01398.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Govier T. Social trust and human communities. Montreal, QC: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ozawa S, Paina L, Qiu M. Exploring pathways for building trust in vaccination and strengthening health system resilience. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16(Suppl 7). 10.1186/s12913-016-1867-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shapin S. A Social History of Truth: Civility and Science in Seventeenth-Century England. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. O’Neill O. Trust, trustworthiness, and accountability : Morris N, Vines D, Capital failure: rebuilding trust in financial services. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014: 172–92. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bourdieu P Outline of a theory of practice. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mauss M. Techniques and Technology : Schlanger N, Techniques, technology, and civilization. New York, NY: Berghan Books, 2006: 147–54. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schlanger N. Introduction : Schlanger N, Techniques, technology, and civilization. New York, NY: Berghan Books, 2006: 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mauss M. Debate on the Origins of Human Technology : Schlanger N, Techniques, technology, and civilization. New York, NY: Berghan Books, 2006: 55–6. [Google Scholar]

- 32. de Certeau M. The practice of everyday life: “making do”: uses and tactics : Spiegel GM, Practicing history: new directions in historical writing after the linguistic turn. New York, NY: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, 2004: 213–23. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Graham JE, Abramowitz S, Thiongane O, et al. . Enhancing detection and response for future interventions: building sustainable community-based capacity through experiences of mobile lab and clinical trial interventions. Refereed poster presented at 3 separate scholarly conferences, including. Halifax: IWK Global Health Conference, 2017, 17 January. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Government of Canada , 2014. Chapter 2 - Scope and Approach, Section B: Approach to Research Ethics Board Review, Concepts of Risks and Potential Benefits. In: TCPS 2: Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans. Available: http://www.pre.ethics.gc.ca/eng/policy-politique/initiatives/tcps2-eptc2/chapter2-chapitre2/ch2_en [Accessed Jun 2018].

- 35. Graham JE, Jones M. Just evidence: Opening health knowledge to a parliament of evidence : MacDonald BH, Soomai SS, De Santo EM, et al., Science, information, and policy interface for effective coastal and Ocean management. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2016: 325–49. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Levin N, Leonelli S. How does one “open” science? Questions of value in biological research. Sci Technol Human Values 2017;42:280–305. 10.1177/0162243916672071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Birch K. Rethinking value in the bio-economy: finance, assetization, and the management of value. Sci Technol Human Values 2017;42:460–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Richards P. Ebola: How a people’s science helped end an epidemic. London: Zed Books, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mauss M. The Divisions of Sociology : Schlanger N, Techniques, technology, and civilization. New York: Berghan Books, 2006: 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mol A, Moser I, Pols J, Care in practice: On tinkering in clinics, homes and farms (Vol 8). Bielefeld: Verlag, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mauss M. Techniques of the Body : Schlanger N, Techniques, technology, and civilization. New York, NY: Berghan Books, 2006: 75–96. [Google Scholar]

- 42. World Health Organization Ebola situation reports: Democratic Republic of the Congo. Available: https://www.who.int/ebola/situation-reports/drc-2018/en/ [Accessed Dec 2018].

- 43. Maxmen A. Ebola detectives race to identify hidden sources of infection as outbreak spreads. Nature 2018;564:175 https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-07618-0 10.1038/d41586-018-07618-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Belluz J, 2018. The risk of Ebola spreading beyond the Democratic Republic of Congo is “very high.”. Available: https://www.vox.com/2018/9/25/17903092/drc-ebola-outbreak-war-kivu [Accessed Oct 2018].

- 45. Wazwaz N. Congo Rebels Kill 15, Threaten Ebola Containment Efforts Again. NPR. Available: https://www.npr.org/2018/10/21/659297776/congo-rebels-kill-15-threaten-ebola-containment-efforts-again [Accessed Oct 2018].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjgh-2018-001272supp001.pdf (103KB, pdf)