Abstract

Background:

This study was undertaken to determine if a clinically relevant drug-drug interaction occurred between ibuprofen and lumacaftor/ivacaftor.

Methods:

Peak ibuprofen plasma concentrations were measured prior to and after lumacaftor/ivacaftor initiation. A Wilcoxon signed rank sum test was used to compare the values.

Results:

Nine patients were included in the final analysis. Peak ibuprofen plasma concentrations decreased an average of 36.4 mcg/mL after initiation of lumacaftor/ivacaftor with a relative reduction of 41.7%. The average peak plasma concentration was 84.2 mcg/mL (SD = 10.9) prior to lumacaftor/ivacaftor initiation and 47.9 mcg/mL (SD = 16.4) following initiation (P = 0.0039). Peak concentrations occurred at an average of 100 min (SD = 30) and 107 min (SD = 40) prior to and following lumacaftor/ivacaftor initiation, respectively.

Conclusions:

We suggest a clinically relevant drug-drug interaction exists between ibuprofen and lumacaftor/ivacaftor. Lumacaftor may cause subtherapeutic ibuprofen plasma concentrations due to the induction of CYP enzymes and increased metabolism of ibuprofen. Based on this analysis, we have modified our use of ibuprofen in several patients after evaluation of this drug-drug interaction.

Keywords: cystic fibrosis, drug interactions, pharmacology

1 |. BACKGROUND

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a genetic disorder that results from a defect in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein. This defect impairs the transport of chloride ions and water across the cell membrane, leading to a buildup of thick mucus throughout several organ systems including the lungs, pancreas, liver, and reproductive system. There are many treatments for CF, most of which are designed to maintain lung function, prevent progression of disease, and alleviate symptoms. Currently, the CF Foundation recommends that individuals with CF, between 6 and 17 years of age, with an FEV1 ≥60% predicted, receive chronic oral ibuprofen at doses that produce a peak plasma concentration of 50–100 mcg/mL.1 This recommendation is based on literature by Konstan et al, which showed that high doses of ibuprofen significantly slowed the progression of lung disease when used in conjunction with pharmacokinetic monitoring.2,3

Currently, our center initiates high-dose ibuprofen therapy around 6 years of age. Patients are prescribed a single dose of ibuprofen within the range of 20–25 mg/kg (rounded to nearest tablet strength). They receive a supervised dose during their clinic visit with serial plasma draws at 1, 2, and 3 h post-dose. Patients are instructed to not initiate high-dose ibuprofen therapy at home until therapeutic drug monitoring levels return within the therapeutic range and are deemed appropriate.

As a breakthrough to currently available therapies, the first CFTR modulating drug was approved on January 31, 2012. Ivacaftor (Kalydeco®, Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated, Boston, MA) proved to be effective at treating the underlying cause of CF at the cellular level. On July 2, 2015, a second CFTR modulator, lumacaftor/ivacaftor (Orkambi®, Vertex Pharmaceuticals lncorporated), was approved for CF patients age 12 years and older with two copies of F508del. This was later expanded to patients age 6 years and older on September 28, 2016.

In vitro data suggest that lumacaftor acts as a strong inducer of CYP3A4 enzymes.4 These data also propose potential induction of CYP2B6, CYP2C8, CYP2C9, and CYP2C19 enzymes and inhibition of CYP2C8 and CYP2C9 enzymes. Several of these enzymes play a role in the metabolism of ibuprofen, suggesting that concomitant use of these medications could potentially alter plasma ibuprofen concentrations. This interaction is also proposed in a recent article discussing therapeutic implications of drug-drug interactions in CF.5 As mentioned in the prescribing information, data exist suggesting both induction and inhibition of enzymes; therefore, our study focused solely on the effect of lumacaftor/ivacaftor on the CYP450 substrate, ibuprofen.4 However, to our knowledge, this is one of the first published case series reporting on clinical data of an interaction between ibuprofen and lumacaftor/ivacaftor.

The primary objective of this study was to determine if a clinically relevant drug-drug interaction occurred between ibuprofen and lumacaftor/ivacaftor. This was accomplished by comparing the highest ibuprofen plasma concentrations prior to and after initiation of lumacaftor/ivacaftor.

2 |. METHODS

This study was approved by the University of Iowa Institutional Review Board. We reviewed the electronic medical records of all CF patients up to age 18 years at the Pediatric Cystic Fibrosis Center located within the University of Iowa Stead Family Children’s Hospital, Iowa City, IA from July 2, 2015 until September 30, 2017. To be included in this study, patients were required to have a diagnosis of CF and have concomitant use of lumacaftor/ivacaftor and high-dose ibuprofen. The following information along with patient demographic data was collected from the electronic medical record for patients who met the criteria set forth above: ibuprofen dose, weight, ibuprofen plasma concentrations, date of ibuprofen kinetics before and after lumacaftor/ivacaftor initiation, date of lumacaftor/ivacaftor initiation, liver function tests, and serum creatinine. Concomitant medications were also reviewed for other possible drug-drug interactions that may confound results. Ibuprofen dosing was initially prescribed to achieve plasma concentrations of 50–100 mcg/mL with ibuprofen concentrations drawn per protocol as part of routine clinic care. Ibuprofen plasma concentrations were obtained through ARUP Laboratories (University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT). One lab result was obtained at an alternative facility that was closer to the patient’s home. Exact generic formulation used for each patient was unknown and may not have been consistent for each time period.

A Wilcoxon signed rank sum test was used to compare the mean ibuprofen concentrations before and after starting lumacaftor/ ivacaftor. The analysis was conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3 |. RESULTS

Ten patients met the inclusion criteria for this analysis; however, one patient was excluded due to use of rifampin prior to the ibuprofen therapeutic drug monitoring levels. The proportion of males and females was approximately equal (males = 56%) and the mean age of lumacaftor/ivacaftor initiation was 11.7 years (age range: 9–15 years). There was no identifiable presence of liver or kidney disease in any of the included patients. Additional demographic data can be found in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Demographics

| Pre-lumacaftor/ivacaftor | Post-lumacaftor/ivacaftor | |

|---|---|---|

| Peak ibuprofen plasma concentration(mcg/mL), mean (SD) | 84.2 (10.9) | 47.9 (16.4) |

| Average weight-based ibuprofen dose (mg/kg), mean (SD) | 23.2 (1.8) | 23.0 (1.2) |

| Average absolute ibuprofen dose (mg), mean (SD) | 744.4 (245.5) | 966.7 (300.0) |

| Average AST/ALTa, mean (SD) | 1.3 (0.4) | 1.5 (0.3) |

| Average serum creatinineb(mg/dL), mean (SD) | 0.5 (0.1) | 0.5 (0.1) |

| Average age of pharmacokinetics (years), mean (SD) | 9.7 (2.2) | 12.2 (2.0) |

| Average time from/to most recent ibuprofen kinetics (months), mean (SD) | 23.7 (16.6) | 6.4 (2.5) |

| Average age at start of lumacaftor/ivacaftor (years), mean (SD) | 11.7 (2.0) | |

| Gender, male (%) | 56 |

SD, standard deviation; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase.

Liver function tests were not available for all patients; therefore, only five patients were included in this subset.

Serum creatinine levels were not available for all patients; therefore, only seven patients were included in the pre-lumacaftor/ivacaftorsubset and six in the post-lumacaftor/ivacaftor subset.

Of the included patients, the average dose per weight of ibuprofen was 23.2 mg/kg (standard deviation [SD] = 1.8) prior to initiation of lumacaftor/ivacaftor and 23.0 mg/kg (SD = 1.2) following initiation. Absolute doses ranged from 500 mg to 1400 mg twice daily, with a mean dose of 744 mg prior to initiation and 967 mg following initiation. Ibuprofen plasma concentrations were drawn an average of 24 months prior to lumacaftor/ivacaftor initiation and repeated approximately 6 months following initiation.

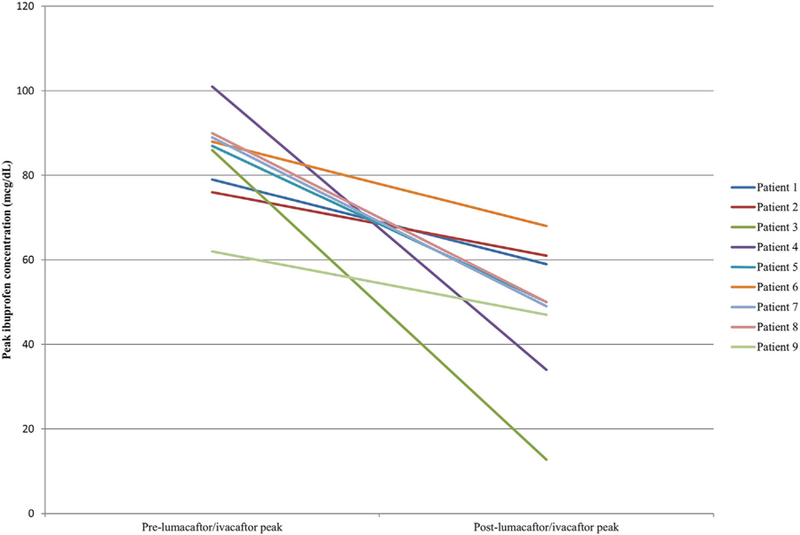

Of the three ibuprofen concentrations obtained for each patient, the highest level was recorded as the peak concentration. The time at which this peak concentration occurred was noted to be the time at peak concentration. The average peak plasma concentration was 84.2 mcg/ mL (SD = 10.9) prior to lumacaftor/ivacaftor initiation and 47.9 mcg/mL (SD = 16.4) following initiation (P = 0.0039). Peak concentrations occurred at an average of 100 min (SD = 30) and 107 min (SD = 40) prior to and following lumacaftor/ivacaftor initiation, respectively. Each patient included in the analysis showed a decrease in peak concentration following drug initiation, which is further illustrated in Table 2 and Figure 1. The average absolute reduction in plasma peak concentration was 36.4 mcg/mL with a relative reduction of 41.7%.

TABLE 2.

Peak ibuprofen plasma kinetics pre- and post-lumacaftor/ivacaftor initiation

| Patient | Lumacaftor/ ivacaftor status | Age (years) | Dose (mg) | Weight (kg) | Weight- based dose (mg/kg) | Time to peak ibuprofen plasma concentration (minutes) | Peak ibuprofen plasma concentration (mcg/mL) | Absolute change in peak ibuprofen plasma concentrations (mcg/mL) | Relative change in peak ibuprofen plasma concentrations (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pre | 8.1 | 500 | 21.3 | 23.5 | 120 | 79 | −20.0 | −25.3 |

| Post | 10.2 | 600 | 24.9 | 24.1 | 120 | 59 | |||

| 2 | Pre | 11.5 | 800 | 36.6 | 21.9 | 120 | 76 | −15.0 | −19.7 |

| Post | 13.5 | 1000 | 46.6 | 21.5 | 120 | 61 | |||

| 3 | Pre | 8.8 | 800 | 31.8 | 25.2 | 120 | 86 | −73.3 | −85.2 |

| Post | 13.0 | 1000 | 44.4 | 22.5 | 180 | 12.7 | |||

| 4 | Pre | 8.2 | 500 | 23.4 | 21.4 | 60 | 101 | −67.0 | −66.3 |

| Post | 9.5 | 600 | 26.6 | 22.6 | 120 | 34 | |||

| 5 | Pre | 11.5 | 800 | 32.2 | 24.8 | 60 | 87 | −37.0 | −42.5 |

| Post | 12.6 | 1000 | 43.0 | 23.3 | 60 | 50 | |||

| 6 | Pre | 10.9 | 1000 | 47.2 | 21.2 | 120 | 88 | −20.0 | −22.7 |

| Post | 12.3 | 1400 | 58.6 | 23.9 | 60 | 68 | |||

| 7 | Pre | 13.5 | 1200 | 57.8 | 20.8 | 120 | 89 | −40.0 | −44.9 |

| Post | 15.5 | 1400 | 66.2 | 21.1 | 120 | 49 | |||

| 8 | Pre | 8.2 | 600 | 24.3 | 24.7 | 60 | 90 | −40.0 | −44.4 |

| Post | 13.4 | 1000 | 43.7 | 22.9 | 120 | 50 | |||

| 9 | Pre | 6.6 | 500 | 20.0 | 25.0 | 120 | 62 | −15.0 | −24.2 |

| Post | 10 | 700 | 24.7 | 28.3 | 60 | 47 | |||

| Average | Pre | 9.7 | 744 | 32.7 | 23.2 | 100 | 84.2 | −36.4 | −41.7 |

| Post | 12.2 | 967 | 42.5 | 23.0 | 107 | 47.9 |

FIGURE 1.

Ibuprofen concentrations before and after lumacaftor/ivacaftor initiation (each patient shown in a different shade of grayscale)

4 |. DISCUSSION

Current literature and recommendations continue to support the use of high-dose ibuprofen in pediatric CF patients. However, new therapies have suggested potential drug-drug interactions, posing a question regarding the clinical significance of these interactions. In this study, we evaluated plasma ibuprofen concentrations obtained through therapeutic drug monitoring before and after initiation of lumacaftor/ivacaftor. Over the 27-month period, all nine patients had lower peak ibuprofen concentrations following initiation of the CFTR modulator and nearly half had subtherapeutic concentrations. One possible rationale for this occurrence is the induction of CYP enzymes by lumacaftor, resulting in faster metabolism and lower plasma concentrations of the ibuprofen substrate.4 An abstract observing this drug-drug interaction was also presented at the 2017 North American Cystic Fibrosis Conference and showed similar results, including a reduction in peak ibuprofen concentrations following initiation of lumacaftor/ivacaftor.6

As noted, one patient was excluded from the analysis due to use of rifampin, another well-known CYP inducer, up until 2 weeks prior to ibuprofen therapeutic drug monitoring. This was the only instance that showed a lower ibuprofen peak plasma concentration within the pre-lumacaftor/ivacaftor phase. This pattern is likely explained by the strong enzyme induction exerted by rifampin.

An additional three patients (not included in the analysis) had therapeutic drug monitoring levels drawn only after lumacaftor/ ivacaftor initiation. All three of these patients’ peak concentrations were subtherapeutic, with the peak concentration averaging 41.7 mcg/mL. These patients received an average dose per weight of 22.6 mg/kg with an absolute dose range of 500–600 mg twice daily.

There are several limitations to this study. First, it was a retrospective chart review with a small sample size. Second, each patient was responsible for bringing in their own dose of ibuprofen to clinic; therefore, exact generic and actual bioavailability was variable and could have impacted pharmacokinetic parameters between the time periods. Additionally, timing of repeat ibuprofen pharmacokinetics in regards to lumacaftor/ivacaftor initiation was not consistent between patients and may have imposed an additional variable into the assessment. It is important to note that, while ibuprofen dosing regimens may have been further optimized at future visits, the intensive process of retesting levels at a subsequent visit was often declined by providers and/or patients due to the time involved. Lastly, blood samples were not routinely tested for all data collection points (i.e., liver and kidney function). However, absence of hepatic and renal dysfunction was confirmed through review of the electronic medical record.

In conclusion, our data suggest a clinically relevant drug-drug interaction exists between ibuprofen and lumacaftor/ivacaftor. This is clinically important as current literature and recommendations support the use of both medications in the pediatric CF patient. While there are no head-to-head trials comparing these therapies and their effect on lung function, our center feels that the long-term safety and efficacy as well as ease of administration and dosing favors the CFTR modulators. With this new information, we have discontinued ibuprofen in several patients due to subtherapeutic ibuprofen concentrations and lack of desire to complete repeat testing. We propose using caution with concomitant use of ibuprofen and lumacaftor/ivacaftor following the analysis of these data as the current results demonstrate that lumacaftor induces the metabolism of ibuprofen, resulting in subtherapeutic concentrations. If concomitant use is desired, we recommend repeating ibuprofen pharmacokinetics following lumacaftor/ivacaftor initiation and adjusting the dose of ibuprofen, if necessary.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Flume PA, O’sullivan BP, Robinson KA, et al. Cystic fibrosis pulmonary guidelines: chronic medications for maintenance of lung health. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:957–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Konstan MW, Byard PJ, Hoppel CL, Davis PB. Effect of high-dose ibuprofen in patients with cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med 1995;332:848–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Konstan MW, Hoppel CL, Chai B, Davis PB. Ibuprofen in children with cystic fibrosis: pharmacokinetics and adverse effects. J Pediatr 1991;118:956–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated. Orkambi [package insert] Boston, MA: Vertex Pharmaceuticals Incorporated; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jordan CL, Noah TL, Henry MM. Therapeutic challenges posed by critical drug-drug interactions in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 2016;51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roesch E, Lee J, Konstan M. Effect of lumacaftor/ivacaftor on the pharmacokinetics of ibuprofen in CF. Pediatr Pulmonol 2017;52. [Google Scholar]