Abstract

Background and Purpose

Recent landmark trials provided overwhelming evidence for effectiveness of endovascular stroke therapy (EST). Yet, the impact of these trials on clinical practice and effectiveness of EST among lower volume centers remains poorly characterized. Here, we determine population level patterns in EST performance in U.S. hospitals, and compare EST outcomes from higher versus lower volume centers.

Methods

Using validated diagnosis codes from data on all discharges from hospitals and Emergency Rooms in Florida (2006 – 2016) and the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) (2012 – 2016) we identified patients with acute ischemic stroke (AIS) treated with EST. Primary endpoint was good discharge outcome defined as discharge to home or acute rehabilitation facility. Multivariable regression adjusted for medical co-morbidities, IV tPA usage and annual hospital stroke volume were used to evaluate the likelihood of good outcome over time and by annual hospital EST volume.

Results

A total of 3890 patients (median age, 73 [61–82] years, 51% female) with EST were identified in the Florida cohort and 42505 (age 69 [58 – 79], 50% female) in the NIS. In both FL and the NIS, the number of hospitals performing EST increased continuously. Increasing numbers of EST procedures were performed at lower annual EST volume hospitals over the studied time period. In adjusted multivariate regression, there was a continuous increase in the likelihood of good outcomes among patients treated in hospitals with increasing annual EST procedures per year (OR, 1.1; 95 CI, 1.1–1.2 in FL and OR, 1.3; 95 CI, 1.2–1.4 in NIS).

Conclusions

Analysis of large population-level data of patients treated with EST from 2006–2016 demonstrated an increase in the number of centers performing EST, resulting in a greater number of procedures performed at lower volume centers. There was a positive association between EST volume and favorable discharge outcomes in EST-performing hospitals over time.

Keywords: Ischemic stroke, endovascular treatment, outcome, epidemiology

INTRODUCTION

Following the landmark clinical trials published in 2015, endovascular stroke therapy (EST) has been established as a key component of acute ischemic stroke (AIS) care1–5. These studies demonstrated that EST leads to dramatic improvements in patient outcomes in combination with medical management versus medical management alone. However, in the wake of these results, stroke systems of care around the globe are now faced with the daunting task of ensuring that patients with AIS have access to appropriate screening and therapy.

The evidence of benefit for EST that emerged from these trials was derived from treatments rendered almost exclusively at high volume stroke centers. However, since the publication and adoption of these findings into guidelines, it has become well-established that the likelihood of good neurologic outcome for these patients remains dependent on minimizing delays in treatment6. Even 15-minute delays in endovascular reperfusion have been associated with quantifiable decrements in clinical outcomes. As such, there has been an increase in demand for the procedure as well as calls for the dissemination of the treatment away from tertiary-care referral centers into the community, to avoid the costly delays associated with transferring patients7,8. On the other hand, transferring EST patients to higher volume centers has also been associated with reduced mortality9.

Given the need to structure stroke systems of care in the modern EST era, as well as the potential expansion of the procedure away from tertiary-care referral centers and into lower volume centers, understanding the trends in treatment patterns as well as outcomes in relation to treatment volumes is of vital importance. To date, little is known about real-world practice and outcomes of EST. In this study, we examined practice patterns of EST over a 10-year period in a large cohort, and evaluated the association between clinical outcomes and hospital treatment volumes.

METHODS

This article adheres to the American Heart Association Journals implementation of the Transparency and Openness Promotion Guidelines. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Study Design

We performed a retrospective cross-sectional study using data from two complementary cohorts. The first cohort consisted of all Emergency Department (ED) visits and inpatient discharges from nonfederal acute care hospitals in Florida (FL) from 2006 through 2016. The Florida Agency for Health Care Administration provides these data to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality for its Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Florida was chosen because it is a large, demographically and socioeconomically diverse state, with a mixture of urban and rural populations. In addition, Florida’s data allow for deidentified tracking of individual patients by a unique linkage variable across ED and inpatient encounters. Of note, in 2004 the Florida state legislature defined two types of stroke centers (Primary and Comprehensive) according to criteria set by the Joint Commission, and required all EMS providers to use triage assessment tools to evaluate, treat, and transport stroke patients to the most appropriate hospitals10.

In order to assess the generalizability of the findings from this state-wide cohort, we also examined a nation-wide cohort. The National Inpatient Sample (NIS) is the largest publically available inpatient health care database in the US. Beginning in 2012, the NIS approximates a 20% stratified sample of all discharges from US hospitals, including data on all patients, regardless of payer and the uninsured. At present 46 states plus the District of Columbia, are included11. In this study, NIS data from 2012 to 2016 were used. Whereas the FL state cohort allows for tracking of individual patients and as such, additional granularity, the NIS data are weighed to provide nationwide estimates. All analyses were conducted as per HCUP data use agreements. Analyses of deidentified and publicly available data did not warrant an institutional review of this study.

Study Population

To identify the study population, we used diagnoses and procedures codes from the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) system. For data from 2006 through the 3rd quarter of 2015, data were classified using the 9th Revision Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes, while data from the 4th quarter of 2015 and all of 2016 were classified using the 10th Revision Clinical Modification (ICD-10 CM) codes. Codes were derived from prior relevant literature for consistency and comparison12.

In both the FL and NIS, our study population consisted of all patients aged 18 years or older with a diagnosis of AIS who were treated with EST. AIS was defined using previously validated ICD-9 and ICD-10 coding algorithms13. For patients identified using ICD-9 coding, we used 433.x1, 434.x1, or 436 in any hospital discharge diagnosis code position without a primary hospital discharge diagnosis code for rehabilitation (V57) or any accompanying codes for trauma (800–804 or 850–854), intracerebral hemorrhage (431), or subarachnoid hemorrhage (430). For patients identified using ICD-10 coding, we used I61, I63 and I64. EST was defined using specific cerebral thrombectomy procedural codes (39.74 and 03CG3ZZ, ICD-9 and ICD-10, respectively), as was intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (IV tPA) administration (99.10 and 3E03317, ICD-9 and ICD-10, respectively).

In the FL cohort, we then cross-referenced each patient in our cohort that was treated with EST to identify any ED encounters within 1 day prior to the EST treatment. By doing so, we were able to identify patients that were treated with IV tPA at centers other than the EST-performing hospital and then transferred for the procedure, in a “drip and ship” paradigm. We also then tabulated the total number of patients transferred to receive EST at a different center. Note that this analysis was performed in the FL cohort but not the Nationwide sample, as the NIS datasets do not allow for tracking of individual patients across multiple encounters.

Exposure, Outcome and Covariates

Total numbers of EST treatments were tabulated for each hospital in both cohorts during the study period. A hospital was considered “EST-performing” if it performed one or more EST procedures within that calendar year. Annual thrombectomy volume was also analyzed by year of initiation of EST procedures. A composite score of comorbidities using the Charlson comorbidity index was calculated. This index is a validated approach widely used by health researchers to measure a patient’s overall burden of disease14,15. Other medical co-morbidities including hypertension and diabetes were defined using HCUP standardized definitions16.

The primary clinical outcome was patients’ discharge destination (i.e. disposition), which previous studies have shown to correlate with functional status in patients with stroke17. These data were derived from the HCUP meta-label DISPUNIFORM, which provides discharge disposition information on all patients included in the dataset. Good outcome was defined as discharge to home or acute rehabilitation hospital, and poor outcome as discharge to skilled nursing facility, hospice or in-hospital mortality. Secondary endpoints included hospital length of stay and in-hospital mortality. In the FL cohort, we also examined these endpoints in patients treated at EST-performing hospitals who did not receive EST, to evaluate the effect of hospital-specific factors on these outcomes. This analysis could not be performed in the NIS as only a sample of admissions per hospital are tracked.

Because there are multiple other factors that influence patient outcomes after stroke that are not captured in population-level clinical databases including availability of specialized stroke rehabilitation, nursing, neurosurgery, neuroimaging, and many other features, we also adjusted these analyses by hospital annual stroke volume, as higher annual volume centers are more likely to benefit from these advantages, and because this parameter has been shown to correspond with discharge outcomes18.

Statistical Analysis

Univariate analysis of categorical variables was performed using Fisher’s exact test. Analyses using the NIS data were performed using survey design methods, accounting for sampling weights11. Multivariate logistic regression analyses adjusting for age (in quartiles), sex, race, Charlson index and IV tPA usage were used to evaluate the association between year of treatment and annual EST volume on the primary and secondary clinical outcomes. Higher vs. lower volume hospitals were defined in several ways. First, higher volume centers were defined as centers performing greater than or equal to the median number of procedures annually, and lower volume centers as those performing fewer. Then, yearly EST treatment volume was examined as an ordinal variable by tens (1–10, 11–20, 21–30, 31–40, 41–50, >50). The Hosmer-Lemeshow test of goodness of fit was used in these regression models. Data from 2008 onwards were used in the logistic regression models because annual hospital EST volumes were low before this year. Results are presented as odds ratio (OR) with associated 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) or median (interquartile range [IQR]). Analyses were performed using StataMP 14 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX) and Prism 7 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA) statistical software.

RESULTS

Our study comprised 3,890 patients who underwent EST in our state-wide cohort and 42,505 in the NIS. Basic demographics between the two cohorts were comparable (Table I in the online-only Data Supplement), though the FL cohort was slightly older and had a greater percentage of Hispanic patients. Data from 56 hospitals performing EST between 2006 and 2016 in Florida were included, and 2,260 hospitals from 2012 to 2016 in the nation-wide cohort.

In the FL cohort as shown in Table 1, median age was 73 [61–82] years, 51% were women, and 61% were white. Across the entire cohort, 47% had hypertension, 27% had diabetes and the median Charlson comorbidity index was 3. Nearly half the patients were treated with IV tPA prior to EST. The median number of EST procedures per hospital per year was 24 (IQR, 12–45). Patients treated at higher volume centers (i.e., hospitals that performed greater than or equal to the median number of EST procedures annually) received IV tPA before EST less often (38% vs. 50%, p=<0.001 Fisher’s exact test) than patients treated at lower volume centers (i.e. hospitals that performed fewer than the median number of EST procedures annually). The Charlson comorbidity index was similar between the two groups.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics.

| All Patients (n=3890) |

Patients treated at Lower Annual Volume

Centers (> 24) (n=1974) |

Patients Treated at Higher Annual Volume

Centers (≤ 24) (n=1916) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (median [IQR]) | 73 [61 – 82] | 72 [60 – 81] | 73 [62 – 82] |

| Female Sex | 1997 (51%) | 984 (50%) | 1013 (53%) |

| Race | |||

| - White | 2311 (61%) | 1290 (66%) | 1021 (55%) |

| - Black | 612 (16%) | 305 (16%) | 307 (17%) |

| - Hispanic | 749 (20%) | 298 (15%) | 451 (24%) |

| IV tPA | 1704 (44%) | 983 (50%) | 721 (38%) |

| Comorbidities | |||

| - Hypertension | 1815 (47%) | 925 (47%) | 890 (47%) |

| - Smoking | 359 (9%) | 196 (10%) | 163 (9%) |

| - Dyslipidemia | 1017 (26%) | 487 (25%) | 530 (28%) |

| - Renal Failure | 318 (8%) | 159 (8%) | 159 (8%) |

| - Diabetes | 1056 (27%) | 521 (26%) | 535 (28%) |

| - Charlson Index | 3 [3–4] | 3 [3–4] | 3 [2–4] |

Data represented as median [IQR] or n(%). IQR: Interquartile range.

Trends in Hospital Volumes and EST – State-level Cohort

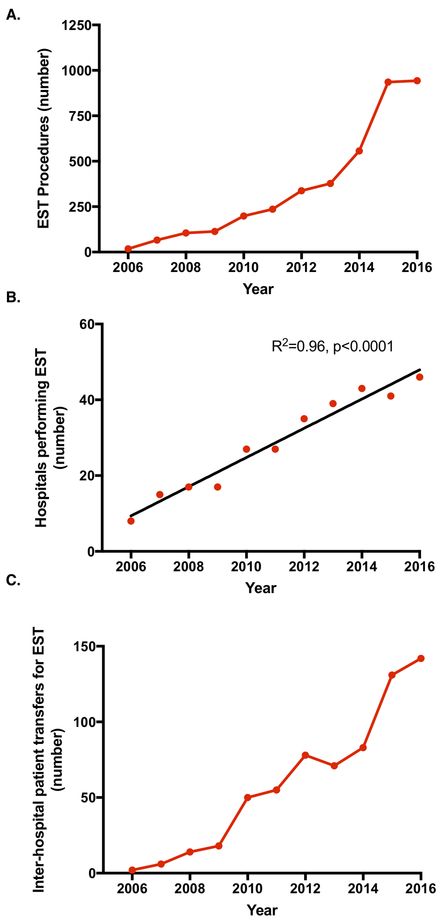

In FL, there was a continuous increase in the number of EST procedures performed annually from 2006–2016, aside from a large jump in 2015 (Figure 1A), which was followed by a plateau. We observed a corresponding increase in the number of hospitals performing EST over this time period, as shown in Figure 1B, with a 4-fold increase in number over the study period, and an average increase of approximately 4 hospitals per year. While the number of procedures plateaued between 2015 and 2016, the number of hospitals performing the procedure continued to increase. The median annual EST volume per EST-performing center increased over this time period, with 2 (IQR, 1–3]) in 2006 to 5 (IQR, 4–10) in 2011 to 9 (IQR, 3–14) in 2013 to 14 (IQR, 6–31) in 2016. There was also a steady increase in the number of patients transferred for EST, as shown in Figure 1C. The rate of change of patient transfers largely mirrored the rate of change of EST procedures. Most patients who were transferred for EST did not receive IV tPA prior to transfer (87%).

Figure 1.

Annual trends in EST procedures performed in Florida (2006 – 2016). (a) Total EST procedures performed by year. (b) Total number of hospitals performing at least 1 EST procedure by year. On average, the number of EST-capable hospitals increased by 4 per year. (c) Total number of patient transfers from one Emergency Department to another hospital for EST.

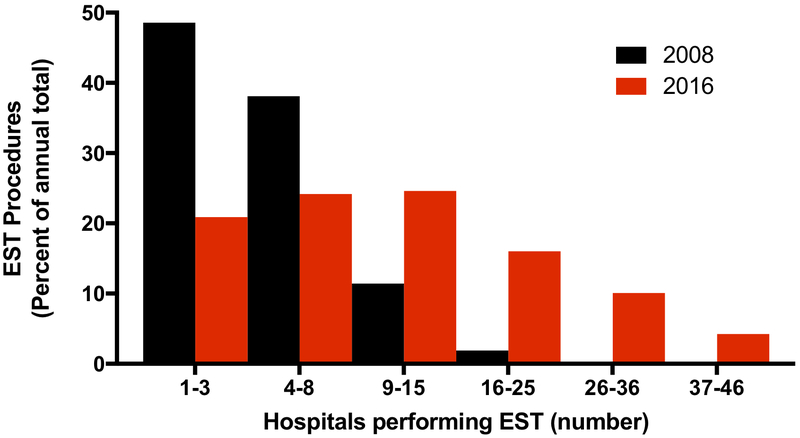

As shown in Figure 2, earlier in the FL cohort the majority of EST procedures were concentrated in a handful of hospitals, with 49% (51/105) of the procedures performed in 3 hospitals and 87% (91/105) performed across the top 8 hospitals in 2008. This figure presents the percentage of total annual EST procedures against the number of EST-performing hospitals in histogram bins, ordered by decreasing annual volume. By 2016, the number of hospitals performing EST increased and the distribution had shifted. In comparison, the top 3 hospitals performed 21% (197/943), and the top 8 hospitals 45% (425/943), in 2016. EST procedures were more evenly distributed across this larger number of EST-performing centers.

Figure 2.

Distribution of EST procedures in hospitals performing EST in Florida. Histogram depicting the percentage of annual total EST procedures versus total number of hospital divided into bins for 2008 and 2016. Hospitals were divided into bins by ranking of total number of annual EST procedures.

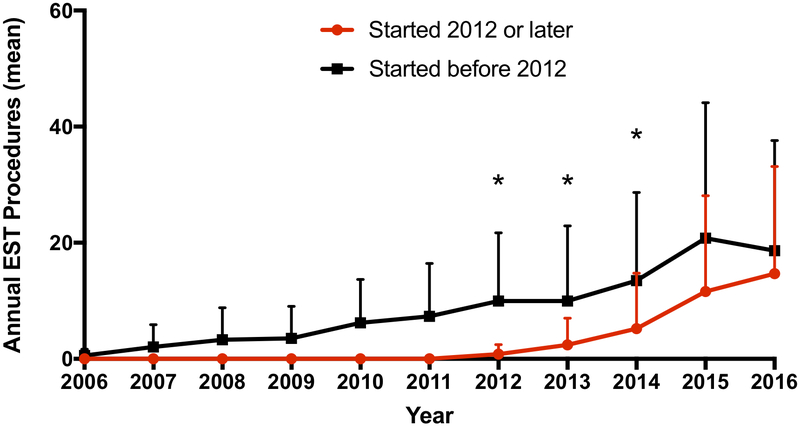

Because many of the centers performing EST later in the cohort were non-EST-performing centers earlier in the cohort, we studied the rate of growth of annual EST volume for centers that had been performing the procedure from the onset of the cohort versus those that began performing the treatment later in the cohort. As shown in Figure 3, in the FL cohort for both centers that started prior to 2012 as well as those that began in 2012 or later, the annual EST procedure volume increased. The rate of growth of annual EST volume was greater in centers that started more recently, and the difference in annual volume between these two types of EST-performing centers was no longer significant in 2015 and 2016. Of note, despite the overall increase in annual EST volume for EST-performing hospitals over the time course of the cohort, a substantial proportion of treatments continued to occur in lower volume centers. As shown in Figure I in the online-only Data Supplement, for the FL cohort in 2016 26% of procedures were performed at centers with fewer than 20 EST treatments per year. Of note, a very small percentage of patients that were transferred from one hospital to another came from a center that was also an EST-performing center (<1%).

Figure 3.

Growth of annual EST procedures by time of initial EST procedure. Mean (± SEM) annual EST procedures for hospitals that began performing EST procedures prior to 2012 and those that began in 2012 or later versus time.

Trends in Hospital Volumes and EST – National Inpatient Sample

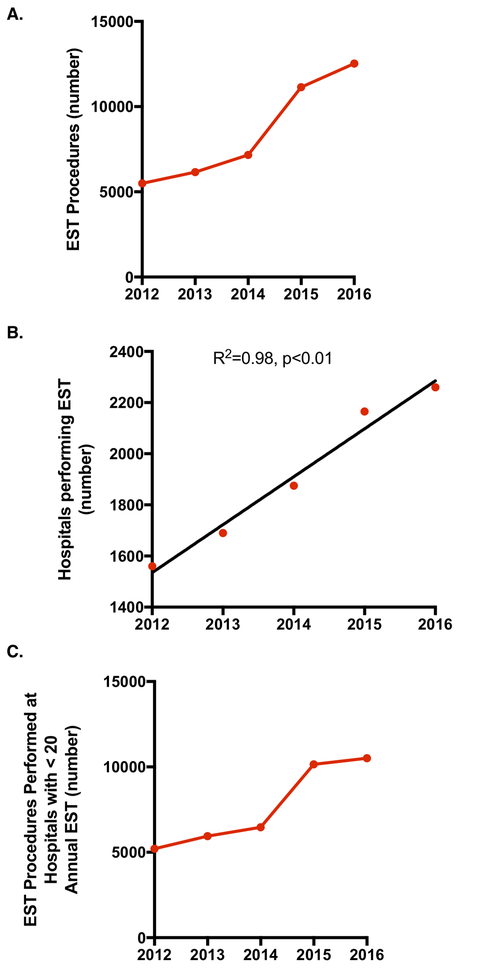

To assess the generalizability of the state-level cohort findings, we studied trends in EST procedures across a nation-wide sample. As shown in Figure 4, we observed a very comparable linear increase in the number of EST procedures performed, with a large jump in 2015 followed by a leveling off. Similarly, there was a increase in the number of hospitals performing EST, with an average increase of approximately 188 hospitals per year. In addition, while the number of procedures leveled off between 2015 and 2016, the number of hospitals performing the procedure continued to increase. Along with the increase in number of EST procedures was an increase in the number of procedures performed at hospitals with fewer than 20 annual treatments (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Annual trends in EST procedures performed in Nation-wide cohort (2012 – 2016). (a) Total EST procedures performed by year. (b) Total number of hospitals performing at least 1 EST procedure by year. On average, the number of EST-capable hospitals increased by 188 per year. (c) Total number of EST procedures performed at hospital performing fewer than 20 procedures per year.

Outcomes following EST

In multivariate regression analysis adjusted for IV tPA administration, age, sex, race, Charlson index and annual hospital stroke volume we observed a significant increase in the likelihood of good discharge outcomes over the 10-year period of our cohort. The likelihood of discharge to home or acute rehabilitation facility improved over time for patients treated with EST (OR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.1–1.2) in FL and in the NIS (OR, 1.2; 95 CI, 1.1–1.2). In the both cohorts, the likelihood of good clinical outcome was greater in patients who had been treated with IV tPA (OR, 1.3; 95 CI, 1.1–1.6) in FL and in the nation-wide cohort (OR, 1.3; 95 CI, 1.2–1.5). In addition, the likelihood of good discharge outcomes also improved with increasing annual EST procedural volume. As shown in Figure II in the online-only Data Supplement, there was a continuous increase in the likelihood of good discharge outcomes among patients treated in hospitals with increasing annual procedures per year (OR, 1.1; 95% CI, 1.1–1.2) in FL, after adjusting for IV tPA administration, age, sex, race, Charlson index and annual hospital stroke volume. These findings were maintained in the nation-wide cohort (OR, 1.3; 95% CI, 1.2–1.4). For AIS patients evaluated at EST-capable centers who were not treated with EST in the FL cohort, there was no effect on discharge outcomes by annual hospital EST volume (OR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.83–1.1).

In secondary outcome analysis, the likelihood of in-hospital mortality also decreased with increasing annual EST volume. In adjusted multivariate logistic regression, greater annual EST volume was associated with decreased likelihood of inpatient mortality for patients treated with EST in FL (OR, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.8–0.9) and in the nation-wide cohort (OR, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.7–0.9). For AIS patients who were not treated with EST, there was no significant effect on the likelihood of inpatient mortality by annual EST volume in FL (OR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.62–1.03). In adjusted linear regression, there was no effect of annual EST volume on total length of inpatient stay for patients treated with EST (coefficient 0.09; 95% CI, 0.3–0.5 in FL and coefficient −0.4; 95% CI, −0.8–0.2 in nation-wide cohort).

DISCUSSION

In this large population-level study of patients treated with EST from 2006 through 2016, we observed a linear increase in annual treatment rates over time, with a large jump in 2015 corresponding to the release of multiple, positive randomized clinical trials. This increase in procedural volume was matched by an increase in the number of centers performing EST, with a resulting shift in distribution of procedures across a substantially greater number of hospitals. Hospitals that began performing EST mid-way through the cohort in 2012 saw a rapid growth of procedural volume and had comparable annual treatment numbers to those that had been performing EST in 2006 by 2015. Procedural outcomes improved over time as well, which may have been related to improvements in EST-devices and techniques. We also found improved outcomes for treatments performed at hospitals with increasing annual volume.

Stroke systems of care across the globe are currently faced with the challenge of developing the best methods to triage patients with large vessel occlusions to ensure that eligible patients have access to EST19–21. A wide range of solutions have been proposed, with some supporting a massive expansion in the number of EST-capable hospitals and providers to increase the number of local and community centers that can provide these services22. Others have developed plans to concentrate procedural expertise in providers, but expand the number of centers supporting EST, by transporting the EST-capable physicians to the community hospitals, as opposed to transferring the patient23. Mobile stroke units have been suggested as another potential means of bringing the physician to the patient, and avoiding excess drip and ship time. Finally, some have argued for continuing to concentrate both hospital and proceduralist expertise in tertiary referral centers and transferring patients from the community to these hub hospitals or directly routing patients from the pre-hospital setting24. This argument is supported by data demonstrating reduced mortality in EST patients transferred to higher volume centers, relative to lower volume centers9. Determining which system of care works best may ultimately depend in a large part on local geographies and medical resource availability. However, data on “real world” treatment trends such as those presented here are important to inform these decisions.

It should also be noted that the data supporting improved clinical outcomes in patients treated with EST have almost exclusively been derived from higher volume centers with comprehensive AIS care [1–5]. While the distribution of EST to smaller centers may reduce time from onset to treatment, these centers frequently cannot match the Neuro-Imaging, Vascular Neurology, Neurosurgery and Rehabilitation capabilities of larger referral centers. As such, the efficacy of EST in lower volume or resource-restricted centers remains undetermined. Prior attempts at “real world” data have relied primarily from EST registries, which fail to address this key issue in AIS care for several reasons8. First, these data do not capture all EST procedures performed in a hospital, as enrolling centers are free to pick and choose the patients they enroll. This selection bias limits the generalizability of these clinical outcomes. In addition, often times only high-volume centers are given the opportunity to participate in these registries. Thus, outcomes from lower volume centers are not represented. This limitation has led to some healthcare systems, including the Ministry of Health of Brazil, to require a recapitulation of prior clinical trial findings in their specific settings prior to acceptance of their results25. Our findings corroborate the concept that the findings seen in the randomized EST trials may not be generalizable to every setting. Indeed, given our study’s findings of OR 1.1 (Florida) and 1.3 (Nationwide) for good outcome per 10 additional annual EST procedures, the question of whether EST is effective at lower volume centers can be raised. On the other hand, while the likelihood of good outcome at lower volume centers in our study was lower than those of higher volume centers, would these patients who were treated at lower volume centers have done better or worse had they been transferred to another hospital, and had their treatment delayed or not performed at all?

It should also be noted that over the time course of this study, newer EST devices, which allowed for more effective and safer thrombectomy were released, a chance which would render treatments prior to 2012 poorly representative of modern practice. To date, there have been few prior studies to evaluate volume-outcome relationships for EST in the modern era of EST. Previous studies include a retrospective review of nine centers (442 consecutive patients with EST) that showed lower time to treatment, higher reperfusion rates and better functional outcomes at follow up for patients treated in higher volume centers26. In another study using the NIS in 2008, annual EST was correlated with inpatient mortality27. However, in another analysis using NIS from 2008 to 2011, patients treated at lower EST volume hospitals were not associated with greater odds of inpatient mortality after adjusting for multiple confounders. In addition, similar trends of increased mortality have been observed for outcomes following IV tPA administration, as well as in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage28,29. In this study, we observed a continuous improvement in the rate of good outcomes with increasing annual EST hospital volume. This finding suggests improvements in patient selection, technical performance of EST and/or post-procedure care with neurocritical care and neuroscience nurses may justify concentrating EST care at specialized centers, and also demonstrates that prior studies examining older cohorts may not be relevant in current practice paradigms.

In this study we found lower rates of IV tPA usage amongst EST-treated patients at higher volume centers relative to lower volume centers. It should be noted that our data does not allow for adjustment by time-to-treatment. As such, this finding may be due to the fact that greater number of tPA-ineligible patients were evaluated and treated at higher volume centers, perhaps because of time of presentation relative to last known well time, or increased medical complexity. Our analysis demonstrated a significantly lower risk of post procedural ischemic/hemorrhagic complications or death following MT in patients who received IV tPA as compared to MT alone, though better outcomes with IV tPA administration may partly be derived from a shorter time to treatment, and thus a potentially lower core infarct size at baseline. Data on this topic have been mixed in the literature, and it is the subject of ongoing randomized clinical studies.

While improved EST outcomes at higher volume centers is logical and consistent with prior studies as discussed above, these findings should not be extrapolated to imply that all stroke systems of care should focus on concentrating EST treatments at only a few high volume centers rather than disseminating EST treatments more widely. In some regions, distance, cost and time make such transfers impractical. Further, although our analyses attempted to control for important variables affecting outcome, patients receiving EST at lower volume community hospitals may differ in important ways from those at higher volume centers, and in ways for which we are unable to adjust. As such, further data are needed to address this issue.

Our study has a number of limitations. As mentioned above, beyond annual EST volume, there are a number of other hospital characteristics including quality of Neuro-Imaging, critical care and nursing that affect outcomes following large vessel occlusion stroke. Here we attempt to partially adjust for these differences by controlling for annual stroke volume as larger stroke centers are more likely to benefit from these additional resources. However, because these factors are not directly measurable, we are not able to quantify the reasons behind the improved outcomes observed in patients treated in higher volume centers. In addition, the clinical benefit conferred by EST has been shown to be dependent on several factors including time from onset to recanalization, as well as occlusion location, degree of reperfusion, and extent of pre-procedural infarct to name a few. In this analysis, we are not able to account for these features. However, because the characteristics of patients with stroke presenting over the time course of our study are unlikely to have changed significantly, our finding of continuously improved outcomes over time would not be affected by this limitation, and could reflect improvements across a number of different areas including patient selection, treatment and post-procedure care. Further, additional outcomes measures including long-term disability as well as quality of life indicators are needed to provide a richer description of the patients’ post-stroke experience. While our analysis focused on discharge outcomes, these outcomes have been shown to correlate well with longer term functional outcomes17.

An evaluation of existing trends using population-based aggregate data is of paramount importance for designing future networks and policies for stroke care to develop optimal infrastructures to accommodate the demand created by novel endovascular therapeutics. We believe our study is the first to provide a long-term analysis of treatment trends in EST that extends to the modern EST era and suggests that patients treated with EST at higher-volume centers have better outcomes than those treated at lower volume centers. Further exploration of this relationship and the role of patient transfers with additional studies will be needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Disclosures

Dr. Blackburn reports funding from National Institutes of Health (K23 NS106054).

References

- 1.Saver JL, Goyal M, Bonafe A, Diener H- C, Levy EI, Pereira VM, et al. Stent-Retriever Thrombectomy after Intravenous t-PA vs. t-PA Alone in Stroke. N. Engl. J. Med 2015; 372:2285–2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berkhemer OA, Fransen PSS, Beumer D, van den Berg LA, Lingsma HF, Yoo AJ, et al. A Randomized Trial of Intraarterial Treatment for Acute Ischemic Stroke. N. Engl. J. Med 2015;372:11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell BCV, Mitchell PJ, Kleinig TJ, Dewey HM, Churilov L, Yassi N, et al. Endovascular Therapy for Ischemic Stroke with Perfusion-Imaging Selection. N. Engl. J. Med 2015;372:1009–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goyal M, Demchuk AM, Menon BK, Eesa M, Rempel JL, Thornton J, et al. Randomized Assessment of Rapid Endovascular Treatment of Ischemic Stroke. N. Engl. J. Med 2015;372:1019–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jovin TG, Chamorro A, Cobo E, de Miquel MA, Molina CA, Rovira A, et al. Thrombectomy within 8 Hours after Symptom Onset in Ischemic Stroke. N. Engl. J. Med 2015;372:2296–2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saver JL, Goyal M, van der Lugt A, Menon BK, Majoie CBLM, Dippel DW, et al. Time to Treatment With Endovascular Thrombectomy and Outcomes From Ischemic Stroke: A Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316:1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grotta JC, Lyden P, Brott T. Rethinking Training and Distribution of Vascular Neurology Interventionists in the Era of Thrombectomy. Stroke. 2017; 48:2313–2317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Froehler MT, Saver JL, Zaidat OO, Jahan R, Aziz-Sultan MA, Klucznik RP, et al. Interhospital Transfer Before Thrombectomy Is Associated With Delayed Treatment and Worse Outcome in the STRATIS Registry (Systematic Evaluation of Patients Treated With Neurothrombectomy Devices for Acute Ischemic Stroke). Circulation. 2017;136:2311–2321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rinaldo L, Brinjikji W, Rabinstein AA. Transfer to High-Volume Centers Associated With Reduced Mortality After Endovascular Treatment of Acute Stroke. Stroke [Internet]. 2017;48:1316–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.CDC. A SUMMARY OF PRIMARY STROKE CENTER POLICY IN THE UNITED STATES. https://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/pubs/docs/primary_stroke_center_report.pdf. Accessed December 25, 2018.

- 11.HCUP-US NIS Overview. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp. Accessed December 25, 2018.

- 12.Kamel H, Navi BB, Sriram N, Hovsepian DA, Devereux RB, Elkind MSV. Risk of a Thrombotic Event after the 6-Week Postpartum Period. N. Engl. J. Med 2014;370:1307–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tirschwell DL, Longstreth WT. Validating Administrative Data in Stroke Research; Stroke. 2002;33:2465–2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J. Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, Fushimi K, Graham P, Hider P, et al. Updating and Validating the Charlson Comorbidity Index and Score for Risk Adjustment in Hospital Discharge Abstracts Using Data From 6 Countries. Am. J. Epidemiol 2011;173:676–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.NIS Description of Data Elements. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/nisdde.jsp. Accessed December 25, 2018.

- 17.Kramer AM, Steiner JF, Schlenker RE, Eilertsen TB, Hrincevich CA, Tropea DA, et al. Outcomes and Costs After Hip Fracture and Stroke. A Comparison of Rehabilitation Settings. JAMA. 1997;277:396–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saposnik G, Baibergenova A, O’Donnell M, Hill MD, Kapral MK, Hachinski V, et al. Hospital volume and stroke outcome: Does it matter? Neurology. 2007;69:1142–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwamm LH. Optimizing Prehospital Triage for Patients With Stroke Involving Large Vessel Occlusion. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75:1467–1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Southerland AM, Johnston KC, Molina CA, Selim MH, Kamal N, Goyal M. Suspected Large Vessel Occlusion: Should Emergency Medical Services Transport to the Nearest Primary Stroke Center or Bypass to a Comprehensive Stroke Center With Endovascular Capabilities? Stroke. 2016;47:1965–1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vivanco-Hidalgo RM, Abilleira S, Salvat-Plana M, Ribera A, Gallofré G, Gallofré M. Innovation in Systems of Care in Acute Phase of Ischemic Stroke. The Experience of the Catalan Stroke Programme. Front. Neurol 2018;9:427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alberts MJ, Range J, Spencer W, Cantwell V, Hampel M. Availability of endovascular therapies for cerebrovascular disease at primary stroke centers. Interv. Neuroradiol 2017;23:64–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wei D, Oxley TJ, Nistal DA, Mascitelli JR, Wilson N, Stein L, et al. Mobile Interventional Stroke Teams Lead to Faster Treatment Times for Thrombectomy in Large Vessel Occlusion. Stroke. 2017;48:3295–3300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohamad NF, Hastrup S, Rasmussen M, Andersen MS, Johnsen SP, Andersen G, et al. Bypassing primary stroke centre reduces delay and improves outcomes for patients with large vessel occlusion. Eur. Stroke J 2016;1:85–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.EndoVascular Treatment With Stent-retriever and/or Thromboaspiration vs. Best Medical Therapy in Acute Ischemic Stroke - ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02216643. Accessed December 25, 2018.

- 26.Gupta R, Horev A, Nguyen T, Gandhi D, Wisco D, Glenn BA, et al. Higher volume endovascular stroke centers have faster times to treatment, higher reperfusion rates and higher rates of good clinical outcomes. J. Neurointerv. Surg 2013;5:294–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adamczyk P, Attenello F, Wen G, He S, Russin J, Sanossian N, et al. Mechanical thrombectomy in acute stroke: utilization variances and impact of procedural volume on inpatient mortality. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis 2013;22:1263–1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prabhakaran S, Fonarow GC, Smith EE, Liang L, Xian Y, Neely M, et al. Hospital Case Volume Is Associated With Mortality in Patients Hospitalized With Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Neurosurgery. 2014;75:500–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saver JL, Fonarow GC, Smith EE, Reeves MJ, Grau-Sepulveda MV, Pan W, et al. Time to Treatment With Intravenous Tissue Plasminogen Activator and Outcome From Acute Ischemic Stroke. JAMA. 2013;309:2480–2488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.