Abstract

In this article, we address three questions concerning the long-term effects of parenting-focused preventive interventions: 1) Do prevention programs promote effective parenting in families facing normative stressors as well as those facing frequent adversity? 2) Do parenting programs prevent children’s long-term problems? 3) Do changes in parenting mediate long-term effects of programs? We address these questions by summarizing evidence from 22 programs with randomized trials and followups of three years or longer. We describe in more detail two interventions for divorced and bereaved families, suggesting that they prevent a range of problems and promote a range of developmental competencies over a prolonged period. Program effects to strengthen parenting mediated many of these long-term outcomes.

Keywords: parenting programs, prevention, long-term effect

Developmental studies link optimal parenting with less frequent problems in children in a range of domains, including mental and physical health, substance use, and academic achievement (1–3). Effective parenting has also been associated with more optimal outcomes for children exposed to a range of adverse conditions, such as poverty and the divorce or death of parents (4, 5). However, questions have been raised about whether such evidence reflects a causal role of parenting or can be explained by the effects of other factors, such as shared genes or other environmental conditions (6). The question about the causal role of parenting has critical practical and theoretical implications. The most scientifically rigorous way to establish a causal role of parenting is to test whether strengthening parenting experimentally affects children’s outcomes positively over time (1, 7).

In this article, we update our earlier review (5) of the long-term effects from randomized trials of prevention-focused parenting programs by extending the time to three years after the intervention ended and including additional studies. We chose to extend the time period to three years to increase the likelihood of assessing outcomes that last across developmental periods. Our review includes 22 programs (described in Table S, available online) that had a component targeting parenting and a randomized comparison condition, demonstrated a significant effect on parenting at one or more assessments, and tested effects on children’s problems or competencies three or more years after the intervention ended. We addressed three questions: 1) Do prevention programs promote effective long-term parenting? 2) Do such programs reduce children’s long-term problems? 3) What are the pathways through which parenting mediates program effects on long-term outcomes? The programs focus on children across phases of development and ethnic groups, and include youth going through normal developmental transitions (e.g., transition to high school) as well as those experiencing serious adversities (e.g., poverty, parents’ mental illness, parents’ separation). All programs are considered prevention interventions (either universal, selective, or indicated) rather than treatment interventions for children who were experiencing clinical levels of mental health problems.

After addressing these three questions, we turn our focus to two parenting-focused prevention programs to illustrate how theory is used to design prevention parenting programs and how the evaluation of these programs tests the pathways that account for their long-term effects. We conclude the article by discussing the opportunities presented by research on the long-term effects of prevention-focused parenting programs for improving public health and increasing our understanding of developmental processes.

Defining Effective Parenting

Effective parenting includes an affectively positive parent-child relationship, effective discipline practices, advice and guidance, support of children’s skills to adapt to environmental demands (e.g., from school and peers), and discouragement of high-risk behaviors (e.g., substance use). The specific behaviors that constitute effective parenting change across development and, in many families, involve helping children adapt to extraordinary demands due to adversities (e.g., poverty, racism, violence, and stressful family situations) and succeed at normative developmental tasks (e.g., the transition to elementary or high school). Although parenting interventions are often part of a package that promotes other protective factors (e.g., children’s coping), this review focuses on the effects of program-induced changes in parenting.

Do Prevention Programs Promote Effective Parenting in the Long Term?

All of the 22 programs we reviewed reported significant effects to improve parenting at one assessment, and 10 found improvements in some aspect of parenting that lasted 3–15 years after the program ended. Programs reported strengthening a range of parenting behaviors, including increased positive interactions, effective discipline, open communication, problem solving, school involvement, monitoring and talking about high-risk behavior, as well as reducing conflict between parents and children and aversive interactions between parents and children.

Do Prevention Parenting Programs Reduce Long-Term Child Outcomes?

If parenting plays a causal role in children’s development, then promoting effective parenting should foster healthy outcomes and reduce pathological outcomes across all phases of development (1, 7). Twenty of the 22 programs we reviewed reported significant direct effects on outcomes from 3 to 15 years following participation. Significant long-term direct effects were found to reduce externalizing problems (12 programs), internalizing problems (7 programs), substance use/abuse (8 programs), and high-risk sexual behavior (7 programs), and to increase indicators of positive developmental competencies such as self-regulation/self-esteem (9 programs), health outcomes (4 programs), and academic success (4 programs). Consistent with prior evidence of the benefits of parenting interventions (8), 10 programs reported significant long-term direct effects on three or more outcomes. Only one program reported significant effects on parenting but failed to demonstrate either direct or indirect long-term effects on children’s outcomes.

Through What Pathways Does Parenting Mediate Program Effects on Long-Term Outcomes?

Inferences about the causal effect of parenting are stronger when the changes in parenting caused by the intervention are shown to account for (or mediate) program effects on subsequent outcomes (9). In fact, parenting was found to mediate long-term program effects on many domains of outcomes: mental health problems (externalizing, 7 programs; internalizing, 3 programs), substance use/abuse (6 programs), health outcomes (2 programs), sexual behavior (3 programs), academic performance (3 programs), and competence (3 programs). Seven programs reported that parenting mediated program effects on outcomes in more than one domain, such as externalizing and substance use (4 programs) and internalizing and externalizing problems (3 programs).

The results of these interventions support the different pathways through which we have previously proposed that parenting programs change long-term outcomes (5). One pathway consists of direct effects of parenting on long-term child outcomes. Four programs provided support for a direct parenting pathway. For example, an evaluation of the Bridges program for Hispanic youth in transition to high school found that the effects of the program to reduce conflict between parents and children at two years mediated program effects to reduce internalizing, externalizing, and substance use problems five years after the program ended (10). A second pathway involves cascading effects in which changes in parenting reduce children’s problems or promote children’s competencies in the short term, which in turn reduce a different domain of subsequent problems for children. For example, a family-focused preventive intervention with poor, rural, African American families (11) strengthened communication between parents and children, which led to youth internalizing parents’ norms and expectations about high-risk behavior, and this in turn mediated program effects to reduce high-risk sexual behavior and substance use six years later. A third, contextual effects pathway involves changes in parenting to reduce children’s exposure to high-risk situations or promote their exposure to prosocial contexts, which in turn reduce later problems. For example, the Family Check-Up, a brief, motivation-based parenting program, reduced conflict in families of youth in transition to high school, which reduced involvement with deviant peers, and this in turn mediated program effects to reduce externalizing problems up to seven years later (12).

Illustrative Randomized Trials: Promoting Effective Parenting After Divorce and Bereavement

We now present a closer look at two programs—the New Beginnings Program (NBP) and the Family Bereavement Program (FBP)—to illustrate how to design parenting programs based on parenting as a malleable protective factor, test program effects on parenting and children’s long-term outcomes, and assess pathways that mediate long-term program effects. Over the past three decades, we have conducted randomized trials of brief (10- to 12-group sessions) parenting programs for families who experienced divorce (13) and the death of a parent (14). Children in families who experience these disruptions are at increased risk for problems years later; effective parenting is a major protective factor that correlates with more optimal outcomes for children (15, 16). These trials tested experimentally the proposition that promoting effective parenting in families that experience these adversities reduces children’s long-term problems.

Program Effects on Parenting

Both the NBP and the FBP taught similar parenting skills designed to promote effective parenting, including increasing positive family interactions, actively listening to children’s problems and feelings, and engaging in clear and consistent strategies to reduce children’s misbehaviors and boost positive behaviors. They emphasized that parents practice the program skills with their children and figure out how to make these skills work in their families. They also focused on stressors specific to each transition (for the NBP, exposure to interparental conflict; for the FBP, parents’ grief). Both programs led to positive short-term changes in the quality of the relationship between parents and children, and in effective discipline as assessed by reports of many raters (parents and youth) as well as by observing objectively the behavior of parent-child interactions (e.g., positive affective tone; 16, 17). For both programs, positive effects on parenting were maintained six years after the program (for the FBP, d = .33 main effect; 18), with the effect of the NBP being larger for those who were at higher risk at the start of the program (d range of .23 −.34 across measures of parenting; 19). Supporting the programs’ emphasis on practicing skills, parents’ practice at home of program skills with their children mediated program effects to strengthen parenting (20).

Long-Term Effects on Children’s Outcomes

The long-term effects of the NBP on children’s outcomes were assessed six and 15 years after participation. At the six-year followup (when the youth were adolescents), the NBP significantly reduced diagnosed mental disorders by 37% (14.8% NBP versus 23.5% literature controls, Odds Ratio [OR] = 2.70) and the number of sexual partners of the youth (d = .37), and increased grade point average (GPA; d = .26). For youth who were at greater risk when they entered the program (i.e., those who had more externalizing problems and more stressful family environments; 21, 22), the NBP reduced externalizing problems, internalizing problems, and substance use, and increased competencies, including self-esteem, coping efficacy, educational goals, and job aspirations (13, 23). The effect sizes for the high-risk group ranged from d = .45-.58 (median = .52) for mental health problems and .20-.30 for drug and alcohol use; the effect size for competencies ranged from d = .27-.47 (mean = .35).

At the 15-year followup (when the youth were in emerging adulthood), the NBP reduced the incidence of internalizing disorders from adolescence to early adulthood by 69% (7.55% NBP versus 24.4% literature controls; OR =.26; 24). For males, it also reduced the number of substance use disorders from adolescence to emerging adulthood (d = .40), polydrug use (d = .55), and other drug use (d =.61) in the past year, and substance use problems (d = .50) in the past six months. Also, emerging adults in the NBP spent less time in jail and used fewer services for psychological problems than those in the control condition (25). The NBP also affected biological measures of stress regulation for older participants (26). Furthermore, for those who entered the program at high risk, the NBP led to more positive attitudes toward warm parenting and less positive attitudes toward harsh parenting, suggesting cross-generational benefits of the program (27).

In the six-year followup, the FBP reduced parents’, youth’s, and teachers’ reports of externalizing problems (d = .36) and diagnosed externalizing disorders (15.4% versus 27.4%, adjusted OR = .28) as well as teachers’ reports of internalizing problems (d = .46). The program also led to higher youth self-esteem, grades (for younger children), and educational aspirations (for children with fewer behavior problems at baseline; 20), and to less continuing distressing grief (d = .41; 28). The FBP reduced cortisol dysregulation significantly (29), indicating positive long-term effects of the program on the function of the HPA axis system.

Parenting as Mediator of Long-Term Program Effects on Children’s Outcomes

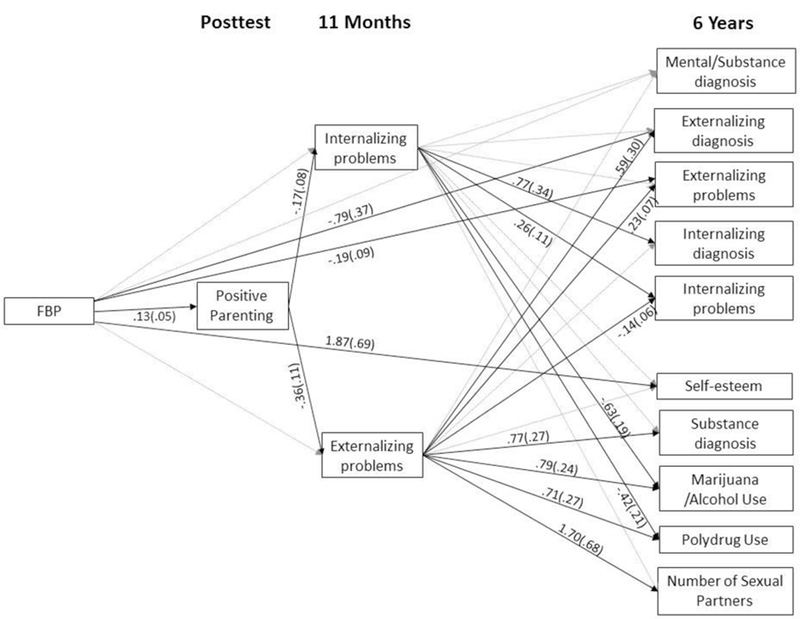

Three studies tested parenting as a mediator of long-term effects of the NBP. In one study (30), improvement in effective discipline at posttest mediated the program effect on GPA at the six-year followup. Also, improvement in the quality of the parent-child relationship at posttest mediated the NBP’s effect on the number of symptoms of mental disorders, externalizing problems, and internalizing problems for those at high risk at the start of the program. In a second study (23), improvements in the quality of the parent-child relationship at posttest mediated increases in children’s coping efficacy at the six-month followup and increases in coping efficacy and active coping at the six-year followup. In a third study (31), which supports a cascading effects model, improvements in parenting reduced children’s problems in the short term, and these, in turn, were associated with positive outcomes for children in the long term. The pathways of the effects of parenting differed for internalizing and externalizing problems. Program effects on parenting (i.e., mother-child relationship) at posttest were related to subsequent decreases in children’s internalizing problems (at the 3- and 6-month followups), which in turn were related to subsequent increases in self-esteem and decreases in symptoms of internalizing disorders in adolescence (at the six-year followup; see Figure 1). Changes in parenting (i.e., effective discipline) at posttest were associated with decreased externalizing problems at the 3- and 6-month followups, which in turn were related to decreases in symptoms of externalizing disorders and substance use, and improvements in GPA at the six-year followup.

Figure 1. Cascading pathways of the effects of the New Beginnings Program on child outcomes over six years.

Note: Solid lines represent significant path coefficients at p ≤ .05; dashed lines represent nonsignificant path coefficients. The direct effects between the NBP and all outcomes were included in the model, but only the significant paths are shown in the figure. M-C denotes the quality of the mother-child relationship. Not shown are baseline measure of parenting and baseline risk, which were included as control variables, and the correlations between the variables assessed at the same time point.

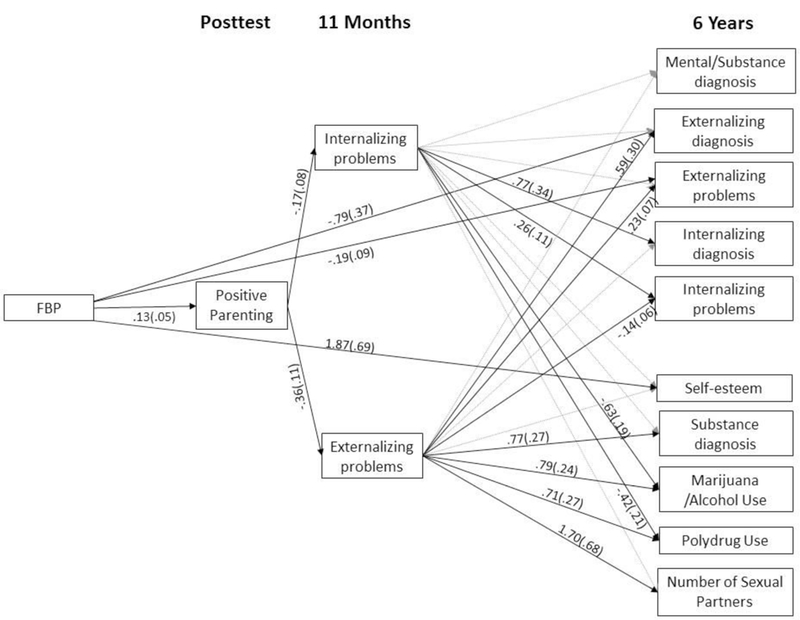

In a study of mediation of the long-term effects of the FBP, reductions in externalizing problems and cortisol dysregulation at the six-year followup were mediated through program effects to increase positive parenting and reduce negative events at posttest and at the 11-month followup (32). We re-analyzed the data to replicate the cascading pathways for the NBP (31). Parenting was defined by a composite of the quality of mother-child relationships and effective discipline in this analysis because these variables correlated at pretest (r = .90; 16). As shown in Figure 2, the FBP strengthened positive parenting at posttest, which in turn was associated with fewer internalizing and externalizing problems at the 11-month followup. Externalizing problems at the 11-month followup were associated positively with externalizing problems, externalizing disorder diagnosis, and substance use at the six-year followup. In addition, externalizing problems at the 11-month followup were linked significantly to high-risk sexual behavior at the six-year followup. Internalizing problems at 11months were associated with more frequent internalizing problems and internalizing disorders at six years. The mediation effects of the internalizing and externalizing pathways were significant (33).

Figure 2. Cascading pathways of the effects of the Family Bereavement Program on child outcomes over six years.

Note: Solid lines represent significant path coefficients at p ≤ . 05; dashed lines represent nonsignificant path coefficients. The direct effects between the FBP and all outcomes were included in the model, but only the significant paths are shown in the figure. Not shown in the graph are baseline measures of parenting and baseline risk, which were included as control variables. Not shown in the graphs are also the correlations between the variables assessed at the same time point. Regression coefficients were unstandardized with standard error in the parenthesis. The effect of FBP on 11-month followup internalizing problems and 6-year followup mental or substance use disorder diagnosis were moderated by baseline risk. For the 11-month followup of internalizing problems, youth with higher risk had lower internalizing problems in the FBP condition as compared with controls. For the 6-year outcomes, youth with lower baseline risk had lower mental health or substance use disorder diagnosis in the FBP compared to those in the control condition. The model accounted for clustering effects for children within families.

These results replicate the NBP’s finding of a significant mediation effect in which program-induced improvements in parenting disrupted the externalizing and internalizing problem pathways that led to later disorders. However, the effects of the FBP to reduce internalizing problems were associated with more frequent substance use six years later. A negative path between internalizing problems and substance use is consistent with previous reports that internalizing problems predict lower levels of problem behaviors and may reflect a lower likelihood that those with internalizing problems will engage in high-risk behavior or associate with deviant peers (34, 35). The negative relation in the FBP sample between externalizing problems at 11months and internalizing problems six years later is surprising and requires replication, but reinforces the need to understand possible unexpected effects of interventions across development.

Looking Ahead: Research To Promote the Public Health and Advance Understanding of Developmental Processes

Evidence of the long-term effects of prevention parenting programs provides a strong scientific foundation for research to develop systems to disseminate and implement such programs. In so doing, such programs can reduce the public-health burden of a range of mental health, substance abuse, and health problems. In the domain of mental health, promoting effective parenting may be the counterpart to efforts such as fluoridation, promoting a healthy diet, and underscoring the importance of physical exercise in the domains of dental and physical health. However, in using parenting programs as a public health strategy, we need to be aware that the trials reviewed in this article were conducted under controlled, experimental conditions. Several studies suggest that parenting programs are less effective when implemented as community-based services delivered at scale than when they are tested in tightly controlled conditions administered by the program developers (36, 37). Researchers need to translate these experimental programs into community-based prevention services and evaluate their effectiveness when delivered under natural conditions.

Evidence concerning pathways that mediate the effects of parenting programs on long-term outcomes presents important scientific opportunities to advance knowledge of the processes underlying healthy and pathological development. Studies report that changing many aspects of parenting (e.g., positive interactions, communication, discipline, monitoring, specific risk-reduction messages) mediated long-term effects on many problems. However, because the studies were conducted with very different populations (e.g., children experiencing different risk factors at different developmental periods), it is difficult to make broad generalizations about mediational pathways. Researchers need to assess what aspects of parenting can be promoted at what phase of development to affect which developmental outcomes. In several studies, changes in parenting mediated long-term outcomes through a cascading effect. For example, parenting effects on externalizing problems mediated program effects on many outcomes, including substance use, high-risk sex, and academic success six years later in both the NBP and the FBP trials. These studies demonstrate that the pathway from externalizing to many problem outcomes is malleable through experimentally induced changes in parenting, adding to prior passive longitudinal studies that found long-term relationships between earlier externalizing problems and this complex of outcomes (38).

Looking ahead, studies should test how promoting effective parenting affects more basic developmental processes that underlie these long-term effects. Such studies should probe many levels of understanding, including biological processes (e.g., functioning of the HPA axis), psychological processes (e.g., self-regulation), and social/contextual processes (e.g., bonding to prosocial and antisocial systems). Studies should also investigate the effects of parenting programs on parents’ own functioning (39) and the complex feedback loops among parents’ functioning, parenting, and children’s behavior. Such research should then inform the design of parenting programs that promote more effectively the well-being of children and youth.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The writing of this article was supported by grants from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (R01 DAO26874) and the National Institute of Mental Health (2R01 MH 049155-11A1), which are gratefully acknowledged.

Contributor Information

Irwin Sandler, Arizona State University.

Alexandra Ingram, Arizona State University.

Sharlene Wolchik, Arizona State University.

Jenn-Yun Tein, Arizona State University.

Emily Winslow, Arizona State University.

References

- 1.Collins WA, Maccoby EE, Steinberg L, Hetherington EM, & Bornstein MH (2000). Contemporary research on parenting: The case for nature and nurture. American Psychologist, 55, 218–232. 10.1037/0003-066X.55.2.218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, & Miller JY (1992). Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: Implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 64–105. 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Repetti RL, Taylor SE, & Seeman TE (2002). Risky families: Family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 330–366. 10.1037/0033-2909.128.2.330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grant KE, Compas BE, Thurm AE, McMahon SD, Gipson PY, Campbell AJ, Kroschock K, & Westerholm RI (2006). Stressors and child and adolescent psychopathology: Evidence of moderating and mediating effects. Clinical Psychology Review, 26, 257–283. 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sandler IN, Schoenfelder EN, Wolchik SA, & MacKinnon DP (2011). Long-term impact of prevention programs to promote effective parenting: Lasting effects but uncertain processes. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 299–329. 10.1146/annurev.psych.121208.131619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris JR (1998). The nurture assumption: Why children turn out the way they do New York, NY: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cicchetti D, & Hinshaw SP (2002). Editorial: Prevention and intervention science: Contributions to developmental theory. Development and Psychopathology, 14, 667–671. doi: 10.1017.S0954579402004017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hale DR, Fitzgerald-Yau N, & Viner RM (2014). A systematic review of effective interventions for reducing multiple health risk behaviors in adolescence. American Journal of Public Health, 104, 19–41. 10.2105/AJPH [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masten ASC, & Cicchetti D (2010). Developmental cascades. Development and Psychopathology, 22, 491–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jensen MR, Wong JJ, Gonzales NA, Dumka LE, Millsap R, & Coxe S (2014). Long-term effects of a universal family intervention: Mediation through parent-adolescent conflict. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 43, 415–427. 10.1080/15374416.2014.891228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murry VM, McNair LD, Myers SS, Chen YF, & Brody GH (2014). Intervention induced changes in perceptions of parenting and risk opportunities among rural African American youths. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23, 422–436. 10.1007/s10826-013-9714-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Ryzin MJ, & Dishion TJ (2012). The impact of a family-centered intervention on the ecology of adolescent antisocial behavior: Modeling developmental sequelae and trajectories during adolescence. Development and Psychopathology, 24, 1139–1155. 10.1017/S0954579412000582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolchik SA, Sandler I, Weiss L, & Winslow EB (2007). New Beginnings: An empirically-based program to help divorced mothers promote resilience in their children. Breismeister JM & Schaefer CE (Ed.), Handbook of parent training: Helping parents prevent and solve problem behaviors New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sandler IN, Wolchik SA, Ayers TS, Tein JY, & Luecken L (2013). Family Bereavement Program (FBP) approach to promoting resilience following the death of a parent. Family Science, 4, 87–94. 10.1080/19424620.2013.821763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sandler I, Wolchik S, Winslow E, Mahrer N, Moran J, & Weinstock D (2012). Quality of maternal and paternal parenting following separation and divorce. In Drozd KKL (Ed.), Parenting plan evaluations: Applied research for the family court (pp. 85–123). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sandler IN, Ayers TS, Wolchik SA, Tein JY, Kwok OM, Haine RA, … & Griffin WA (2003). The Family Bereavement Program: Efficacy evaluation of a theory-based prevention program for parentally bereaved children and adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 587–600. 10.1037/0022-006X.71.3.587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolchik SA, West SG, Sandler IN, Tein JY, Coatsworth D, Lengua L, … & Griffin WA (2000). An experimental evaluation of theory-based mother and mother–child programs for children of divorce. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 843–856. 10.1037/0022-006X.68.5.843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hagan MJ, Tein JY, Sandler IN, Wolchik SA, Ayers TS, & Luecken LJ (2012). Strengthening effective parenting practices over the long term: Effects of a preventive intervention for parentally bereaved families. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 41, 177–188. 10.1080/15374416.2012.651996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sigal AB, Wolchik SA, Tein JY, & Sandler IN (2012). Enhancing youth outcomes following parental divorce: A longitudinal study of the effects of the New Beginnings Program on educational and occupational goals. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 41, 150–165. 10.1080/15374416.2012.651992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schoenfelder EN, Tein JY, Wolchik S, & Sandler IN (2014). Effects of the Family Bereavement Program on academic outcomes, educational expectations and job aspirations 6 years later: The mediating role of parenting and youth mental health problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 1–13. 10.1007/s10802-014-9905-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dawson-McClure SR, Sandler IN, Wolchik SA, & Millsap RE (2004). Risk as a moderator of the effects of prevention programs for children from divorced families: A six-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 32, 175–190. 10.1023/B:JACP.0000019769.75578.79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tein JY, Sandler IN, Braver SL, & Wolchik SA (2013). Development of a brief parent-report risk index for children following parental divorce. Journal of Family Psychology, 27, 925–936. 10.1037/a0034571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Velez CE, Wolchik SA, Tein JY, & Sandler IN (2011). Protecting children from the consequences of divorce: A longitudinal study of the effects of parenting on children’s coping processes. Child Development, 82, 244–257. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01553.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wolchik SA, Sandler IN, Tein J-Y, Mahrer NE, Millsap RE, Winslow E, & Reed A (2013). Fifteen year follow-up of a randomized trial of a preventive intervention for divorced families: Effects on mental health and substance use outcomes in young adulthood. Journal of Clinical and Consulting Psychology, 81, 600–673. 10.1037/a0033235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herman PM, Mahrer NE, Wolchik SA, Jones S & Sandler IN (2014). Cost-benefit analysis of a preventive intervention for divorced families: Reduction in mental health and justice system service use costs 15 years later. Prevention Science, 1–11. 10.1007/s11121-014-0527-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luecken LJ, Hagan MJ, Mahrer NE, Wolchik SA, Sandler IN, & Tein J-Y (2014). Effects of a prevention program for divorced families on youth cortisol reactivity 15 years later. Psychology & Health. Advance online publication 10.1080/08870446.2014.983924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mahrer NE, Winslow E, Wolchik SA, Tein JY & Sandler IN (2014). Effects of a preventive parenting intervention for divorced families on the intergenerational transmission of parenting attitudes in young adult offspring. Child Development, 85, 2091–2105. 10.1111/cdev.12258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandler IN, Ma Y, Tein JY, Ayers TS, Wolchik S, Kennedy C, & Millsap R (2010). Long-term effects of the Family Bereavement Program on multiple indicators of grief in parentally bereaved children and adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78, 131–143. 10.1037/a0018393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luecken LJ, Hagan M, Sandler IN, Tein J-Y, Ayers T, & Wolchik SA (2010). Cortisol levels six-years after participation in the Family Bereavement Program. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 35, 785–789. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou Q, Sandler IN, Millsap RE, Wolchik SA, & Dawson-McClure SR (2008). Mother-child relationship quality and effective discipline as mediators of the 6-year effects of the New Beginnings Program for children from divorced families. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76, 579–594. 10.1037/0022-006X.76.4.579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McClain DB, Wolchik SA, Winslow E, Tein JY, Sandler IN, & Millsap RE (2010). Developmental cascade effects of the New Beginnings Program on adolescent adaptation outcomes. Development and Psychopathology, 22, 771–784. 10.1017/S09544759410000453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luecken LJ, Hagan MJ, Sandler IN, Tein JY, Ayers TS, & Wolchik SA (2014). Longitudinal mediators of a randomized prevention program effect on cortisol for youth from parentally bereaved families. Prevention Science, 15, 224–232. 10.1007/s11121-013-0385-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor AB, MacKinnon DP, & Tein JY (2007). Tests of the three-path mediated effect. Organizational Research Methods, 11, 241–269. 10.1177/1094428107300344 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rogosch FA, Oshri A, & Cicchetti D (2010). From child maltreatment to adolescent cannabis abuse and dependence: A developmental cascade model. Development and Psychopathology, 22, 883–897. 10.1017/S0954579410000520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burt KB, Obradovic J, Long JD, & Masten A (2008). The interplay of social competence and psychopathology over 20 years: Testing transactional and cascade models. Child Development, 79, 359–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eisner M, Nagin D, Ribeaud D & Malti T (2012). The effects of a universal parenting program for highly adherent parents: A propensity score matching approach. Prevention Science, 13, 252–266. 10.1007/s11121-011-0266-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gottfredson D, Kumpfer K, Polizzi-Fox D, Wilson D, Puryear V, Beatty P, & Vilmenay M (2006). The Strengthening Washington D.C. Families project: A randomized effectiveness trial of family-based prevention. Prevention Science, 7, 57–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zucker RA, Heitzeg MM, & Nigg JT (2011). Parsing the undercontrol-disinhibition pathway to substance use disorders: A multilevel developmental problem. Child Development Perspectives, 5, 248–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barlow J, Smailagic N, Huband N Roloff V, & Bennett C (2014). Group-based parent training programmes for improving parental psychological health. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 5 10.1002/14651858.CD002020.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.