Overview

Introduction

A combined procedure including open reduction, femoral shortening osteotomy, and an acetabular procedure is often necessary to obtain a desirable result in children of walking age who have a high-riding hip dislocation.

Step 1: Surgical Approach

A careful approach to the femoral head and acetabulum is required to avoid injury to nerves, vessels, and cartilage.

Step 2: Explore the Hip Joint

Make sure to find the true acetabulum and remove all obstacles to femoral head reduction.

Step 3: Femoral Head Reducibility

Check the reducibility of the femoral head in different positions through a full range of hip motion.

Step 4: First Femoral Osteotomy

Expose the proximal part of the femur subperiosteally and make necessary markers for determining the amount of shortening and rotation at the time of osteotomy.

Step 5: Hip Joint Stability

Check femoral head reduction stability with the proximal end of the osteotomized femur.

Step 6: Femoral Shortening

Decide the amount of shortening and rotation for the best femoral head reduction.

Step 7: Pemberton Acetabuloplasty

In cases with a dysplastic acetabulum and inadequate femoral head coverage after reduction, perform a Pemberton osteotomy.

Step 8: Postoperative Management

Apply a hip spica cast, which the patient wears for six weeks; then switch to a hip abduction brace.

Results

The patient shown in Figures 26 through 29 and Video 5 was a three-year and six-month-old girl with bilateral developmental dysplasia of the hip that was discovered late (Figs. 26 and 27).

Introduction

A combined procedure including open reduction, femoral shortening osteotomy, and an acetabular procedure is often necessary to obtain a desirable result in children of walking age who have a high-riding hip dislocation. Since Klisić and Jancović1,2 first introduced the procedure, femoral shortening has been performed as an adjunct in the open reduction of developmental dysplasia of the hip in older children. In 1984, Schoenecker and Strecker3 reported that the rate of stable reductions and satisfactory clinical and radiographic results in children treated with open reduction and femoral shortening was higher than the rate following treatment that included preoperative skeletal traction. Subsequently, a number of favorable results were reported for older children treated with a single-stage combined procedure4-9.

With increasing experience with this treatment modality, the upper age limit for use of this approach to treat late-diagnosed developmental dysplasia of the hip has been extended, and the procedure has been performed even in children older than eight years of age10,11. Gholve et al. predicted that open reduction without concurrent femoral shortening would most likely require a secondary procedure12. Sankar et al. reported the threshold at which femoral osteotomy is required for high dislocation in patients with developmental dysplasia of the hip to be vertical displacement of the proximal part of the femur that is >30% of the pelvic width13. In addition, it is important to determine the necessity for, and amount of, femoral shortening for each individual according to the soft-tissue tension during the operation. In special instances, such as teratologic dislocation or syndromic developmental dysplasia of the hip, femoral shortening osteotomy often is necessary even in children younger than two years of age14.

In our series, patients with bilateral developmental dysplasia of the hip were significantly older at the time of surgery (mean age, thirty-four months) and had a significantly higher Tönnis grade than patients with unilateral dysplasia15. These findings suggest a tendency for patients with bilateral developmental dysplasia of the hip to be more likely to undergo a combined procedure including femoral shortening. The combined procedure with femoral shortening, although technically demanding, helps prevent excessive force that hinders concentric reduction and decreases the risk of complications related to open reduction, especially redislocation and osteonecrosis, that are common in older children. For patients with late-diagnosed bilateral developmental dysplasia of the hip, an asymmetrical result can be problematic, as it was in our reported series15.

Our one-stage combined surgical procedure for the treatment of high dislocation in patients with developmental dysplasia of the hip is performed with the following steps.

Step 1: Surgical Approach

A careful approach to the femoral head and acetabulum is required to avoid injury to nerves, vessels, and cartilage.

Place the patient in a supine position with a towel roll under the buttock and one under the back to tilt up the side on which the operation is to be performed.

Make an anterior ilioinguinal incision that is not directly on the iliac crest (Fig. 1).

Identify the muscle interval between the sartorius and tensor fascia femoris muscles.

Find the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve and protect it with gentle traction medially.

Outline the iliac crest incision (Fig. 2) and incise the iliac apophysis exactly in the midline (Fig. 3). Elevate the iliac apophyseal cartilage and periosteum from each half of the iliac wing with an elevator.

Expose the anterior inferior iliac spine by elevating the periosteum with the hip abductor muscles from the outer cortex of the ilium until the anterior inferior iliac spine is clearly identified.

Identify the tendon of the straight head of the rectus femoris muscle at its origin on the anterior inferior iliac spine. Transect the rectus femoris tendon close to the anterior inferior iliac spine, but leave a short stump for later tendon reattachment (Fig. 4).

Protect and preserve the ascending branch of the anterior femoral circumflex artery, which may be visible in the surgical field at this time.

Bluntly dissect the iliacus muscle belly medial to the ilium and identify the psoas tendon.

Release the tendinous part of the iliopsoas muscle (Fig. 5) at the pelvic rim. Be careful of the femoral neurovascular bundle, which is located immediately medial and anterior to the psoas muscle. The femoral neurovascular bundle can be retracted and protected with a blunt retractor.

Fig. 1.

Markers for skin incisions. ASIS = anterior superior iliac spine.

Fig. 2.

Marker for iliac crest incision. ASIS = anterior superior iliac spine.

Fig. 3.

Iliac crest incision.

Fig. 4.

Straight head of rectus femoris.

Fig. 5.

Iliopsoas tendon.

Step 2: Explore the Hip Joint

Make sure to find the true acetabulum and remove all obstacles to femoral head reduction.

Identify the acetabulum-hip capsule junction. If the femoral head is dislocated, the edge of the acetabulum can be difficult to identify.

Dissect the soft tissue overlying the capsule, including the reflected head of the rectus femoris and abductor muscles and then identify the margin of the joint capsule at the acetabular rim.

Perform a T-shaped capsulotomy near the acetabular rim, including the upper and lower margins of the hip capsule. Make the stem of the T-shaped capsulotomy parallel to the femoral neck and slightly superior to avoid a small inferior capsular flap that can be a hindrance in capsulorrhaphy (Fig. 6).

Identify the ligamentum teres, which is attached to the femoral head (Fig. 7). Transect the ligamentum teres sharply close to the femoral head.

Trace the distal part of the ligamentum teres to the acetabulum (Fig. 8). Remove all of the fibrofatty tissue (pulvinar tissue) from the true acetabulum.

Identify and palpate the tension of the transverse acetabular ligament at the inferior edge of the acetabulum with a finger before releasing it with scissors. Recheck to ensure that there is no tension of the transverse acetabular ligament after release, as remaining transverse acetabular ligament can impede complete reduction of the femoral head.

Fig. 6.

Marker for capsular incision.

Fig. 7.

Ligamentum teres isolated.

Fig. 8.

Ligamentum teres divided, and traced down to the joint.

Step 3: Femoral Head Reducibility

Check the reducibility of the femoral head in different positions through a full range of hip motion.

Attempt to reduce the femoral head with traction and check the soft-tissue tension.

If the femoral head is reducible, place it into the acetabulum under direct vision and test the hip stability in a neutral position as well as in abduction and internal rotation by pushing the femoral head in a cephalad direction.

If the hip is unstable in a neutral position but is stable in abduction and internal rotation, a Pemberton acetabuloplasty is indicated.

When the femoral head is not reducible (Fig. 9, Video 1) or is under great tension when reduced, a femoral shortening osteotomy should be performed.

Fig. 9.

The femoral head is not reducible.

Video 1.

The femoral head is not reducible.

Step 4: First Femoral Osteotomy

Expose the proximal part of the femur subperiosteally and make necessary markers for determining the amount of shortening and rotation at the time of osteotomy.

Start the second incision from the lower tip of the greater trochanter and extend it distally. The length of the incision, usually about 5 to 6 cm, depends on the length of the implant used for fixation of the osteotomy site and the amount of shortening of the proximal part of the femur that is required (Fig. 1).

Expose the femoral shaft by splitting the tensor fasciae latae and elevate the vastus lateralis off the lateral intermuscular septum, coagulating perforating branches of profundus femoris vessel as needed.

Expose the greater trochanter base; make an L-shaped incision at the proximal origin of the vastus lateralis muscle (Fig. 10).

Cut and elevate the periosteum longitudinally, and insert Chandler retractors under the subperiosteal space to expose the femoral shaft.

Insert a Steinmann pin into the femoral neck perpendicular to the femoral shaft just below the greater trochanteric apophysis under fluoroscopic guidance. This pin will serve as a joystick for checking the femoral head position.

Insert a second Steinmann pin in the projected distal femoral segment in the same rotation plane and perpendicular to the shaft of the femur for rotational guidance (Figs. 11, 12, and 13).

Make a transverse mark with an oscillating saw on the femoral shaft at the lower level of the lesser trochanter under fluoroscopic guidance as a marker of the osteotomy site (Fig. 14).

Make another longitudinal mark on the anterior aspect of the proximal part of the shaft as an additional orientation marker for femoral rotation (Fig. 15).

Using a four-hole DCP (dynamic compression plate) as a template, make two predrilled holes at the proximal end for better fixation alignment later (Fig. 16).

Divide the bone with an oscillating saw at the previously marked site (Fig. 17). Make sure that the periosteum is well stripped so that you can manipulate the femoral head position with the proximal Steinmann pin as a joystick.

Fig. 10.

Marker for vastus lateralis incision.

Fig. 11.

Parallel pins inserted for rotational orientation.

Fig. 12.

Parallel pins viewed from caudally.

Fig. 13.

C-arm view showing two pins in parallel position.

Fig. 14.

Marking of the osteotomy site under c-arm fluoroscopy.

Fig. 15.

Additional rotation marker.

Fig. 16.

With use of the plate as a template, two proximal predrilled holes are made.

Fig. 17.

The femur is cut with an oscillating saw at the predetermined marker.

Step 5: Hip Joint Stability

Check femoral head reduction stability with the proximal end of the osteotomized femur.

Manipulate the proximal Steinmann pin to reduce the femoral head under direct vision (Video 2).

Check the coverage of the femoral head and the stability of the reduction and assess the necessity for rotational osteotomy and pelvic osteotomy (Video 3). If the femoral head cannot be reduced in a stable manner or the reduction cannot be maintained unless the proximal fragment is in internal rotation and/or abduction, an additional proximal femoral derotational osteotomy and/or varus osteotomy should be considered.

Once the optimal position is achieved, have the assistant hold the femoral head in an optimum position by holding the proximal Steinmann pin (Fig. 18) and return to the femoral shaft exposure.

Fig. 18.

With use of the proximal Steinmann pin as a joystick, the femoral head is reduced.

Video 2.

After femoral osteotomy, the femoral head is reducible in internal rotation.

Video 3.

The femoral head becomes unstable with external rotation.

Step 6: Femoral Shortening

Decide the amount of shortening and rotation for the best femoral head reduction.

Estimate the amount of shortening from the preoperative standing pelvic anteroposterior radiograph, and measure the amount of step-off at the broken Shenton line. The amount of shortening depends on the height of the dislocation; generally, 1 to 2 cm is required for neglected developmental dysplasia of the hip in a patient between three and five years old and 2 to 3 cm is required for patients between five and eight years old.

Holding the knee in neutral position with gentle tension, in correct rotational axis and angulation, measure the amount of overlapping. The length of overlapping of the bone ends is the amount of femoral shortening required (Figs. 19 and 20).

Resect the shortening section from the proximal end of the distal fragment of the femur (Fig. 21).

Reduce the femoral head into the acetabulum again, using the Steinmann pin as a joystick.

Bring both ends of the femoral shaft together with the femoral head held in a reduced position by the assistant.

Apply a precontoured four-hole DCP or locking plate on the reduced fragments with two holes on the proximal fragment and two holes on the distal fragment.

Insert the proximal-fragment screws into the predrilled holes first.

Use a reduction clamp to hold the distal segment and the plate in the desirable position.

Check the stability of the hip joint under direct vision, or with fluoroscopy if necessary, through the hip range of motion.

Insert the distal-fragment screws and complete the internal fixation in ideal position. At this time, the amount of rotation can be seen from the relative rotation of two Steinmann pins viewed from caudally (Fig. 22). Do not place the distal fragment in excessive external rotation if an acetabular procedure is contemplated. The resected segment from the shortening was approximately 1.2 cm (Fig. 23) in our demonstrated case.

Fig. 19.

The amount of overlapping while the femoral head is in the reduced position is the amount of femoral shortening required.

Fig. 20.

C-arm view showed the amount of shortening required while the femoral head is in a reduced position.

Fig. 21.

The fragment is removed from the proximal end of the distal fragment.

Fig. 22.

The divergence of two Steinmann pins indicates the amount of external rotation (30° in this case) of the distal osteotomy fragment.

Fig. 23.

The fragment, of about 1.2 cm, removed for shortening.

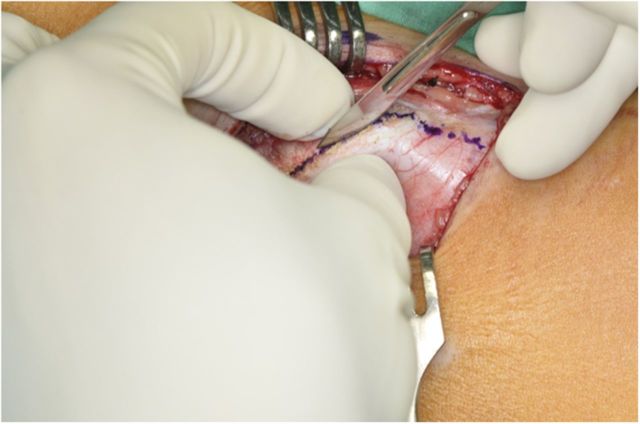

Step 7: Pemberton Acetabuloplasty

In cases with a dysplastic acetabulum and inadequate femoral head coverage after reduction, perform a Pemberton osteotomy.

Details of the Pemberton procedure are described in our previous article16.

The Pemberton procedure was performed in the patient seen in Figures 24 and 25 and Video 4. It provided good femoral head reduction and coverage. The final c-arm view confirmed this finding (Fig. 25).

Close the femoral wound first and have a last look at the hip joint before closing the capsulotomy.

Repair the hip capsule by bringing two lateral flaps close to the acetabulum with tension and under the acetabular flap in a vest-over-pants fashion using number-1 Vicryl (polyglactin) sutures. Have all sutures placed before tying the knots. It is not necessary to resect the redundant capsule.

Repair the tendon of the straight head of the rectus femoris muscle to the anterior inferior iliac spine.

Suture the iliac apophysis over the iliac wing and close the wound.

Fig. 24.

After the Pemberton procedure, the femoral head is in stable position.

Fig. 25.

C-arm view demonstrating a well-reduced hip.

Video 4.

After Pemberton osteotomy, the femoral head is stable with rotation.

Step 8: Postoperative Management

Apply a hip spica cast, which the patient wears for six week; then switch to a hip abduction brace.

Apply a one and a half hip spica cast with the hip in 30° of abduction, 20° of flexion, and neutral to 10° of internal rotation.

Remove the spica cast at six weeks. A hip abduction brace is then used full-time for six weeks and at night for an additional three months.

Results

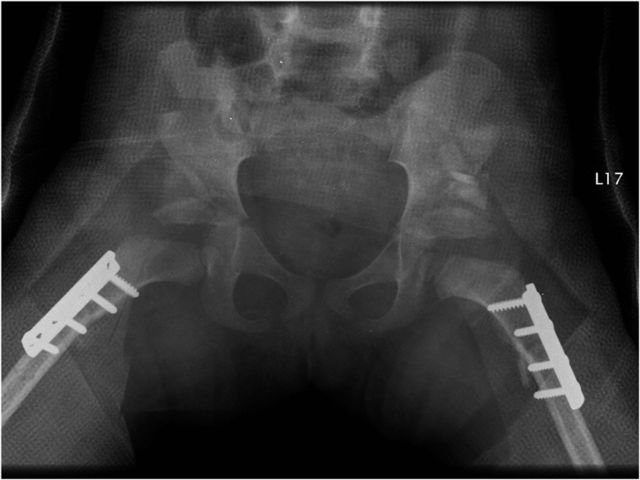

The patient shown in Figures 26 through 29 and Video 5 was a three-year and six-month-old girl with bilateral developmental dysplasia of the hip that was discovered late (Figs. 26 and 27). The three-dimensional computed tomography (CT) scan in 360° of rotation showed a high posterior dislocation (Video 5). The postoperative radiograph revealed good femoral head reduction in a stable position (Fig. 28). The patient subsequently had the same procedure on the left side under a subsequent anesthesia (Fig. 29).

Fig. 26.

Figs. 26 through 29 Illustrative case (also see Video 5). Fig. 26 Standing anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis of a three-year and six-month-old girl with bilateral high dislocation of the hip.

Fig. 29.

Postoperative anteroposterior pelvic radiograph made with the patient wearing a cast after the same procedure on the other side.

Fig. 27.

Bilateral frog-leg lateral pelvic radiograph demonstrating the same high bilateral dislocation with acetabular dysplasia.

Fig. 28.

Postoperative anteroposterior pelvic radiograph made with the patient wearing a cast shows the right femoral head in good position with adequate acetabular coverage. Note that the femoral head often appears in an inferior position immediately postoperatively but will gradually move cephalad to a normal position with time.

Video 5.

Three-dimensional CT scan in 360° of rotation showing high posterior bilateral hip dislocation in the patient shown in Figures 26 through 29.

Figures 30 through 34 show a case with long-term follow-up. The girl presented at the age of three years and three months with bilateral high posterior hip dislocation (Fig. 30). Initially she underwent the index procedure on the right hip (Fig. 31) and then had the left hip procedure three months later (Fig. 32). The nine-month follow-up radiographs showed both hips to be well located (Fig. 33). At ten years postoperatively, when the patient was thirteen years and three months old, the standing pelvic radiograph showed good joint congruity with well-located femoral heads (Fig. 34).

Fig. 30.

Figs. 30 through 34 Illustrative case with long-term follow-up. Fig. 30 Anteroposterior pelvic radiograph of a three-year and three-month-old girl with bilateral high-riding hip dislocation.

Fig. 34.

At ten years postoperatively, both hips were congruent and well located as seen on this anteroposterior pelvic radiograph.

Fig. 31.

Anteroposterior pelvic radiograph following the combined procedure on the right hip.

Fig. 32.

Anteroposterior pelvic radiograph following the combined procedure on the left hip.

Fig. 33.

Anteroposterior pelvic radiograph nine months following the bilateral procedure.

What to Watch For

Indications

The initial treatment for a patient with developmental dysplasia of the hip who is older than three years of age

High teratological or syndromic dislocation even in patients of younger age

Previous failed treatment of a high dislocation or angular/rotational deformities in a patient with developmental dysplasia of the hip

Contraindications

Active infection around the hip area

Severely deformed femoral head as seen radiographically

Small acetabular volume

Closed triradiate cartilage

Pitfalls & Challenges

Determining the amount of shortening

Determining the amount of rotation and/or angular osteotomy

Bone graft dislodgement

Premature triradiate cartilage closure

Excessive Pemberton osteotomy correction may result in osteonecrosis of the femoral head and possibly femoral acetabular impingement in the future.

Clinical Comments

The amount of shortening is important. It should be the right amount to decrease the pressure following reduction, as too much shortening may lead to a lax or less stable hip reduction.

Do not use excessive femoral derotation, as it is preferred to have the pelvic osteotomy compensate for the remainder of the rotational realignment needed.

Usually, a four to five-hole DCP is sufficient for osteotomy site fixation after shortening or derotation. However, if angular correction is required, a locking plate is preferred for fixation.

In the Pemberton osteotomy, internal fixation with Kirschner wires is required if the bone graft is not stable after placement or if the bone is too soft.

Based on an original article: J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013 Jun 19;95(12):1081-6.

Disclosure: None of the authors received payments or services, either directly or indirectly (i.e., via his or her institution), from a third party in support of any aspect of this work. None of the authors, or their institution(s), have had any financial relationship, in the thirty-six months prior to submission of this work, with any entity in the biomedical arena that could be perceived to influence or have the potential to influence what is written in this work. Also, no author has had any other relationships, or has engaged in any other activities, that could be perceived to influence or have the potential to influence what is written in this work. The complete Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest submitted by authors are always provided with the online version of the article.

References

- 1. Klisić P Janković L. Combined procedure of open reduction and shortening of the femur in treatment of congenital dislocation of the hips in older children. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1976 Sep;(119):60-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Klisić P Janković L Basara V. Long-term results of combined operative reduction of the hip in older children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1988 Sep-Oct;8(5):532-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schoenecker PL Strecker WB. Congenital dislocation of the hip in children. Comparison of the effects of femoral shortening and of skeletal traction in treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984 Jan;66(1):21-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shih CH Shih HN. One-stage combined operation of congenital dislocation of the hips in older children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1988 Sep-Oct;8(5):535-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Galpin RD Roach JW Wenger DR Herring JA Birch JG. One-stage treatment of congenital dislocation of the hip in older children, including femoral shortening. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989 Jun;71(5):734-41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vedantam R Capelli AM Schoenecker PL. Pemberton osteotomy for the treatment of developmental dysplasia of the hip in older children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1998 Mar-Apr;18(2):254-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wada A Fujii T Takamura K Yanagida H Taketa M Nakamura T. Pemberton osteotomy for developmental dysplasia of the hip in older children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2003 Jul-Aug;23(4):508-13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Forlin E Munhoz da Cunha LA Figueiredo DC. Treatment of developmental dysplasia of the hip after walking age with open reduction, femoral shortening, and acetabular osteotomy. Orthop Clin North Am. 2006 Apr;37(2):149-60: vi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Subasi M Arslan H Cebesoy O Buyukbebeci O Kapukaya A. Outcome in unilateral or bilateral DDH treated with one-stage combined procedure. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008 Apr;466(4):830-6. Epub 2008 Feb 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. El-Tayeby HM. One-stage hip reconstruction in late neglected developmental dysplasia of the hip presenting in children above 8 years of age. J Child Orthop. 2009 Feb;3(1):11-20. Epub 2008 Sep 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bhuyan BK. Outcome of one-stage treatment of developmental dysplasia of hip in older children. Indian J Orthop. 2012 Sep;46(5):548-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gholve PA Flynn JM Garner MR Millis MB Kim YJ. Predictors for secondary procedures in walking DDH. J Pediatr Orthop. 2012 Apr-May;32(3):282-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sankar WN Tang EY Moseley CF. Predictors of the need for femoral shortening osteotomy during open treatment of developmental dislocation of the hip. J Pediatr Orthop. 2009 Dec;29(8):868-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wenger DR Lee CS Kolman B. Derotational femoral shortening for developmental dislocation of the hip: special indications and results in the child younger than 2 years. J Pediatr Orthop. 1995 Nov-Dec;15(6):768-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang T-M Wu K-W Shih S-F Huang S-C Kuo KN. Outcomes of open reduction for developmental dysplasia of the hip: does bilateral dysplasia have a poorer outcome? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013 Jun 19;95(12):1081-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Huang S-C Wang T-M Wu K-W Fang C-F Kuo KN. Pemberton osteotomy for acetabular dysplasia. JBJS Essential Surg Tech. 2011 Jun 1;94(1):1-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]