Abstract

Rationale:

Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma (IVLBCL) is a type of malignant lymphoma in which neoplastic B cells proliferate selectively within the lumina of small- and medium-sized vessels. Patients with IVLBCL frequently develop neurological manifestations during their disease course. Patients are known to often develop various neurological manifestations, but there are only a few reports of IVLBCL whose initial symptoms are deafness and/or disequilibrium.

Patient concerns:

A 66-year-old Japanese man was provisionally diagnosed with sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Administration of prednisolone did not improve his symptoms, and then he experienced amaurosis fugax. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed multiple brain infarcts, so he was administered antithrombotic drugs. Nevertheless, he experienced recurrent strokes, became irritable, and had visual hallucinations. He was emergently admitted to our hospital with disturbance of consciousness.

Diagnosis:

Blood tests showed elevation of lactose dehydrogenase and soluble interleukin-2 receptor. Cranial MR diffusion-weighted imaging showed multiple lesions bilaterally in the cerebral white matter and cortex, posterior limbs of the internal capsule, and cerebellar hemispheres, which were hypointense on apparent diffusion coefficient maps. Hyperintense lesions were detected bilaterally in the cerebral white matter and basal ganglia on both T2-weighted imaging and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery imaging. Contrast-enhanced brain MRI demonstrated contrast-enhancing high-signal lesions along the cerebral cortex. Brain biopsy revealed a diagnosis of IVLBCL.

Interventions:

The patient could not receive chemotherapy because of his poor general condition. Therefore, we administered high-dose methylprednisolone (mPSL) pulse therapy.

Outcomes:

There was little improvement in consciousness levels after the high-dose mPSL pulse therapy. On the forty-ninth day of hospitalization, he was transferred to another hospital to receive supportive care.

Lessons:

IVLBCL should be regarded as an important differential diagnosis of hearing loss and dizziness. Most importantly, if the symptoms are fluctuant and steroid therapy is not effective, biopsy should be considered as early as possible.

Keywords: brain infarction, dizziness, hearing loss, intravascular large B-cell lymphoma

1. Introduction

Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma (IVLBCL) is a type of malignant lymphoma in which neoplastic B cells proliferate selectively within the lumina of small- and medium-sized vessels, without the involvement of adjacent parenchymal tissue.[1] The incidence of IVLBCL is estimated to be less than 1 person per million.[2] The disease occurs slightly more frequently in men, and most often in the advanced age.[2] IVLBCL usually presents with central nervous system and dermatological lesions in Western countries or with hemophagocytic syndrome in Asian countries, mainly in Japan.[1] Since the progression of the disease is aggressive and rapid, and the prognosis is lethal when the diagnosis and therapy are delayed, early diagnosis is crucial; however, there is not good blood- or CSF-biomarker, and the appearance of MRI findings is not specific. Raising IVLBCL as a differential diagnosis is critically important against nonspecific symptoms. Patients frequently develop neurological manifestations during their disease course, such as encephalopathy, seizure, myelopathy, radiculopathy, or neuropathy.[3] However, there are only a few reports of IVLBCL whose initial symptoms are deafness and/or disequilibrium. Here, we report on a patient with IVLBCL presenting with hearing loss and dizziness.

2. Case presentation

A 66-year-old Japanese man developed hearing loss in the left ear. Five months later, he felt his ear blocked, and he realized tinnitus and dizziness. He consulted an otolaryngologist and was diagnosed with peripheral vertigo. Betahistine mesilate was administered for his symptoms, but no improvement was observed. He consulted another otolaryngologist and was tentatively diagnosed with sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Ten days of intravenous prednisolone partially improved his dizziness, but hearing loss and tinnitus continued. About two months later, he showed transient visual obscuration in the right side, so he saw a neurosurgeon who emergently performed brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). He was diagnosed with amaurosis fugax and cardiac embolisms and was started on apixaban. One month later, his hearing loss in both ears and dizziness worsened. Administration of prednisolone did not relieve his symptoms, and he could not walk without a walker. In brain MRIs, there were several new cerebral infarcts. He became irritated, started to talk and behave illogically, and had visual hallucinations. He repeatedly fell down and could not hold onto anything. One year after the emergence of the initial symptoms, he was admitted to our hospital because of disturbance of consciousness.

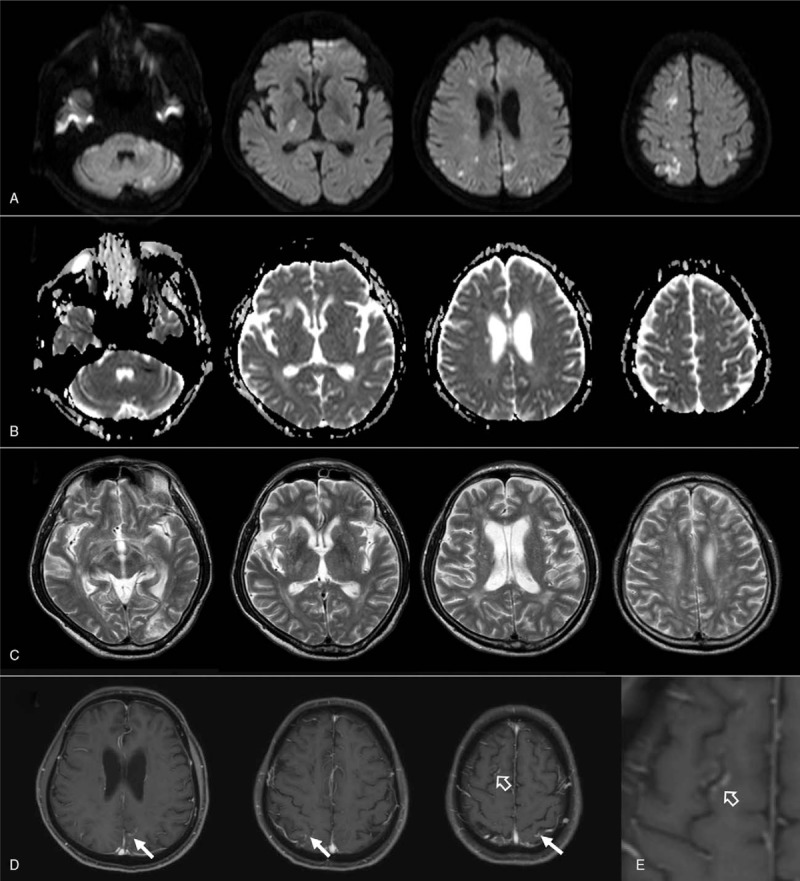

His past medical history included treated hypertension and hyperuricemia. Our physical examination revealed a body temperature of 37.3°C, blood pressure of 118/93 mm Hg, pulse rate of 108/min, respiration rate of 19/min, and peripheral oxygen saturation of 100% with a 3 L/min oxygen mask. His conscious level on arrival was E1V1M5 on the Glasgow Coma Scale. General physical examination results were normal; however, neurological examination revealed a positive doll's eye phenomenon, muscle weakness in the lower extremities, and exaggerated tendon reflexes in all four extremities. No neck stiffness was found, and otoacoustic emissions were compatible with both sensorineural hearing loss. The number of white blood cells was 10,100/μL, and C-reactive protein was 5.59 mg/dL. The patient's blood urea nitrogen was 47.0 mg/dL, creatinine 1.81 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase 41 IU/L, lactase dehydrogenase 267 IU/L, fibrinogen 619.6 mg/dL, and D-dimer 2.0 μg/mL. Serum-soluble interleukin-2 receptor (s-IL2R) was 1290 U/mL, whereas carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9), and prostate-specific antigen were not elevated. Serum lactic acid and pyruvic acid were within normal limits. The patient's thyroid function was normal, and antinuclear, anti-Sjögren's-syndrome (SS)-related antigen A, anti-SSB, proteinase 3-anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic, and myeloperoxidase-anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies were not detected. Syphilis, hepatitis, and HIV serologies were negative. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis showed the following: opening pressure of 160 mm H2O, 3 cells/μL (90% mononuclear, 10% polymorphonuclear), total protein of 85 mg/dL, glucose 71 mg/dL (124 mg/dL in the serum), CEA <0.2 ng/mL, CA19-9 <0.6 U/mL, angiotensin converting enzyme <1.0 U/mL, s-IL2R 60 U/mL, beta 2-microglobulin 3.3 mg/L; neither cytology nor comprehensive microbiological studies showed positive results. Holter electrocardiogram showed no atrial fibrillation, and there were no abnormalities in chest X-ray and transthoracic cardiac ultrasonography. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography showed no malignancies. Cranial MRI revealed hyperintense bilateral lesions in the cerebral white matter and cortex, suggesting multiple watershed infarctions, while diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) showed lesions in the posterior limbs of the internal capsule and cerebellar hemispheres (Fig. 1A). Reduction in signals at those lesions was seen on apparent diffusion coefficient maps (Fig. 1B). There were multiple hyperintense lesions bilaterally in the cerebral white matter and basal ganglia on both T2-weighted (Fig. 1C) and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery imaging (not shown). Magnetic resonance angiography results were normal. Contrast-enhanced brain MRI, performed on the thirteenth day of hospitalization, revealed contrast-enhancing high-signal lesions along the cortex at the level of the right frontal lobe, which were hyperintense on DWI, as well as bilaterally in the parietal lobe and in the left parieto-occipital region (Fig. 1D and E; arrows and open arrows).

Figure 1.

Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance (MR) images on the admission day (A–C) and on the thirteenth day (D–E) of hospitalization. (A) Diffusion-weighted images, showing multiple high-intensity lesions in bilateral cerebral white matter and cortex, posterior limbs of the internal capsule, and cerebellar hemispheres. (B) Apparent diffusion coefficient maps. (C) T2-weighted MR images demonstrating multiple high-intensity areas in bilateral cerebral white matter and basal ganglia. (D and E) Gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted MR images on the thirteenth day of hospitalization showing contrast-enhancing high-signal areas along the cortex in regions of the right frontal lobe (open arrow in D), bilateral parietal lobe, and left parieto-occipital region (arrows in D). The lesion at the right frontal lobe is magnified and demonstrated in (E).

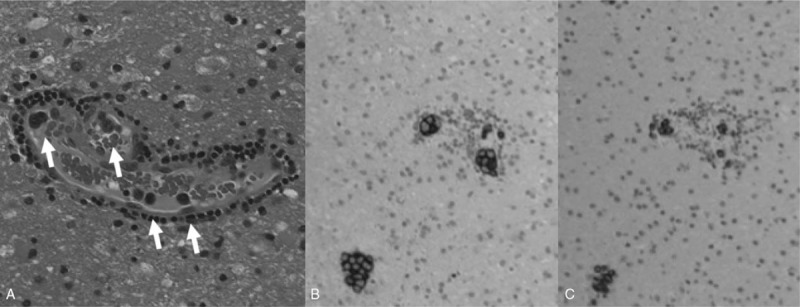

Based on the patient's clinical course, laboratory data, and neuroimaging results, we suspected intravascular lymphoma; however, skin biopsy did not confirm this diagnosis. On the twenty-eighth day of hospitalization, we performed cerebral biopsy of the right frontal lesion. Histopathological examination revealed proliferation of large atypical lymphoid cells in the vessels (Fig. 2A; arrows). Immunohistochemical analysis showed that the neoplastic cells were positive for CD20 (Fig. 2B) and CD79a (Fig. 2C) antigens, B-cell lymphoma 6, multiple myeloma-1, and Ki67 (not shown), thus leading to a diagnosis of IVLBCL.

Figure 2.

Histopathology of the biopsy brain specimen. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin staining showing intravascular proliferation of neoplastic lymphoid cells (arrows). (B) CD20 and (C) CD79a staining. Original magnifications: A, ×200; B and C, ×100.

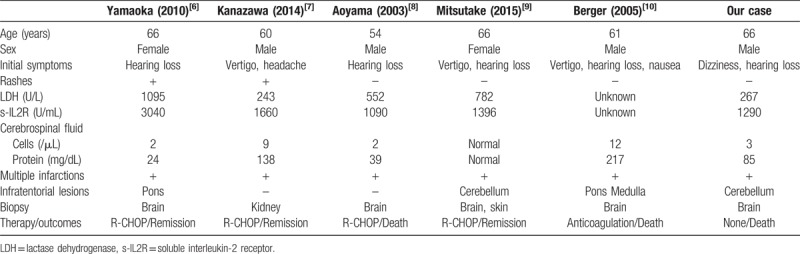

We administered high-dose methylprednisolone pulse therapy (1 g/day, for 3 days), but little improvement of consciousness disturbance was observed. We consulted the department of hematology considering the possibility of chemotherapy, but this was not indicated because of the patient's poor general status. On the forty-ninth day of hospitalization, he was transferred to another hospital to receive the best supportive care. Three days later, he died. The summary is shown in the Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of previously reported cases and ours.

The ethical approval was not necessary because this was a case report. The patient's family provided informed consent for the publication of his clinical data.

3. Discussion

We report the case of a patient with initial symptoms of recurrent hearing loss and dizziness, who developed multiple strokes of unknown origin and required brain biopsy to establish a diagnosis of IVLBCL. Our case resembles that reported in Western countries as the patient did not show cutaneous lesions. Glass et al. reported that over 60% of patients with IVLBCL develop neurological symptoms during their disease course; 76% develop progressive and multifocal cerebrovascular disorder; 38% myelopathy and radiculopathy; 27% subacute encephalopathy; 21% cranial nerve dysfunction; and 5% develop neuropathy.[2] Unfortunately, none of these symptoms is specific to IVLBCL, thus making diagnosis laborious. R-CHOP chemotherapy, which employs rituximab, cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunomycin, vincristine, and prednisolone, can extend life prognosis[1]; therefore, it is essential to diagnose the disease properly in the early stage and distinguish it from cerebral infarction. Tissue biopsy is necessary to diagnose IVLBCL; skin, bone marrow, muscles, peripheral nerves, and brain should be selected for the biopsy. In particular, skin biopsy should be considered first, since it is less invasive than biopsy of other tissues. Nonetheless, many past cases required brain biopsy for the diagnosis of IVLBCL.[4]

Our case was not typical of the disease since the bilateral symptoms fluctuated and he experienced repeated dizzy spells. Only 1.7% of cases of sudden sensorineural hearing loss are reported to show bilateral symptoms,[5] which usually do not fluctuate. As shown in the Table 1, some studies have also reported patients with deafness, dizziness, or both as the initial symptoms.[6–10] Hearing loss was found bilaterally in 3 patients and even unilaterally in 2 patients. In all cases, including ours, multiple lesions were found in the supratentorial region. In some cases, lesions were observed in the brain stem or cerebellum by MRI, but in others, like in our case, no such lesions were found. We propose that the sudden deafness in our patient was caused by infarction of the proper cochlear artery, and that dizziness was caused by the propagation of the occlusion proximally to the level of the labyrinthine artery or the anterior inferior cerebellar artery, although it is difficult to prove this by imaging studies. In 3 patients, brain biopsy was necessary for diagnosis (Table 1).[6,8,10] In contrast, remission was achieved with R-CHOP therapy in 3 cases, and 2 patients died during the course of the chemotherapy.[8,10] In our case, however, when the diagnosis of IVLBCL was confirmed, the patient could not receive R-CHOP therapy because of his poor condition.

4. Conclusion

IVLBCL is a rare but critical cause for hearing loss and dizziness and should be considered as a diagnosis, particularly when the clinical course of the patient is not typical for sudden sensorineural hearing loss and when recurrent strokes occur. Our report highlights the diagnostic role of cerebral biopsy, since skin biopsy, although less invasive, does not always lead to correct diagnosis. Prevalence of IVLBCL among the patients presenting a deafness and dizziness should be clarified.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Editage for English proofreading.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Yasushi Tomidokoro.

Funding acquisition: Yasushi Tomidokoro.

Investigation: Zenshi Miyake, Takao Tsurubuchi, Akira Matsumura, Noriaki Sakamoto, Masayuki Noguchi.

Resources: Yasushi Tomidokoro.

Supervision: Akira Matsumura, Masayuki Noguchi, Akira Tamaoka.

Writing – original draft: Zenshi Miyake.

Writing – review & editing: Yasushi Tomidokoro, Takao Tsurubuchi, Noriaki Sakamoto.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CA19-9 = carbohydrate antigen 19-9, CEA = carcinoembryonic antigen, DWI = diffusion-weighted imaging, IVLBCL = intravascular large B-cell lymphoma, MRI = magnetic resonance imaging, s-IL2R = soluble interleukin-2 receptor.

This work was partially supported by JSPS KAKENHI, Grant Number JP16K15476.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Ponzoni M, Ferreri AJ, Campo E, et al. Definition, diagnosis, and management of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: proposals and perspectives from an international consensus meeting. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:3168–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Orwat DE, Batalis NI. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2012;136:333–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Glass J, Hochberg FH, Miller DC. Intravascular lymphomatosis. A systemic disease with neurologic manifestations. Cancer 1993;71:3156–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Brunet V, Marouan S, Routy JP, et al. Retrospective study of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma cases diagnosed in Quebec: a retrospective study of 29 case reports. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e5985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Fetterman BL, Luxford WM, Saunders JE, et al. Sudden bilateral sensorineural hearing loss. Laryngoscope 1996;106:1347–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Yamaoka Y, Izutsu K, Itoh A, et al. A case of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma with a variety of neurological disorders and skin lesion diagnosed by brain biopsy. Jpn J Stroke 2010;32:406–12. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kanazawa Y, Hagiwara N, Matsuo R, et al. [Case of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma (IVLBCL) with central nervous system symptoms diagnosed by renal biopsy]. Rinsho Shinkeigaku 2014;54:484–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Aoyama M, Aoki T, Matsuura Y, et al. [Dramatic but temporary improvements in a case of CNS intravascular malignant lymphomatosis]. Rinsho Shinkeigaku 2003;43:6–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Mitsutake A, Kanemoto T, Suzuki Y, et al. [A case of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma that presented with recurrent multiple cerebral infarctions and followed an indolent course]. Rinsho Shinkeigaku 2015;55:101–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Berger JR, Jones R, Wilson D. Intravascular lymphomatosis presenting with sudden hearing loss. J Neurol Sci 2005;232:105–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]