Abstract

Rationale:

Pneumocystis jirovecii causes severe pneumonia in immunocompromised hosts. Human immunodeficiency virus infection, malignancy, solid organ or hematopoietic cell transplantation, and primary immune deficiency compose the risk factors for Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) in children, and PCP can be an initial clinical manifestation of primary immune deficiency.

Patient concerns:

A 5-month-old infant presented with cyanosis and tachypnea. He had no previous medical or birth history suggesting primary immune deficiency. He was diagnosed with interstitial pneumonia on admission.

Diagnoses:

He was diagnosed with PCP, and further evaluations revealed underlying X-linked hyper-IgM syndrome.

Interventions:

He was treated with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole for PCP, and eventually received allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for hyper-IgM syndrome.

Outcomes:

Twenty months have passed after transplantation without severe complications.

Lessons:

PCP should be considered in infants presenting with severe interstitial pneumonia even in the absence of evidence of immune deficiency. Primary immune deficiency should also be suspected in infants diagnosed with PCP.

Keywords: hyper-IgM syndrome, infant, Pneumocystis jirovecii

1. Introduction

In children, Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) was mostly reported as epidemics in premature and malnourished infants in the 1940s and 1950s.[1] After then, most cases of PCP developed in children with immunocompromised states, and patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) have comprised a majority of patients with PCP since the 1980s.[2] Accordingly, the suspicion and diagnosis of PCP in children without any evidence of an underlying immunocompromised state are not easy. Primary immune deficiency (PID), as well as HIV infection, malignancy, and transplantation, are known as risk factors for PCP,[3] and PCP can be an initial clinical manifestation of PID.[4–6]

We diagnosed a 5-month-old male infant presenting with cyanosis and interstitial pneumonia with PCP. Although he had no previous history consistent with PID, further evaluation revealed X-linked hyper-IgM (HIGM) syndrome, and he received hematopoietic cell transplantation for the underlying HIGM syndrome. This case report was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul St. Mary's Hospital (Approval No.: KC18ZESI0177). Written informed consent for publication was obtained from the patient's parent.

2. Case presentation

A 5-month-old male infant presented with cyanosis. His mother was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis 16 months before his birth. Pregnancy was identified at the gestational age of 2 months, and medical therapy for rheumatoid arthritis had been discontinued since then. The mother experienced improvement in symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis without medication, and the patient was born via Caesarean section at the gestational age of 39+6 weeks with a birth weight of 4.49 kg. He exhibited no medical problems at or after birth. Two weeks prior, fever, vomiting, and diarrhea developed, and he was treated for acute gastroenteritis at a primary clinic. However, he visited the emergency room and pediatric outpatient clinic of our hospital with persisting vomiting and diarrhea 9 and 6 days before, respectively. His vomiting and diarrhea had continued since then, and moreover, peripheral and central cyanosis accompanied. On admission, he was afebrile and exhibited no respiratory symptoms including cough, rhinorrhea, and sputum. Pulse oxymetry showed SpO2 of 45% in room air, which rose to 95% with oxygen supplied at 4 L/min.

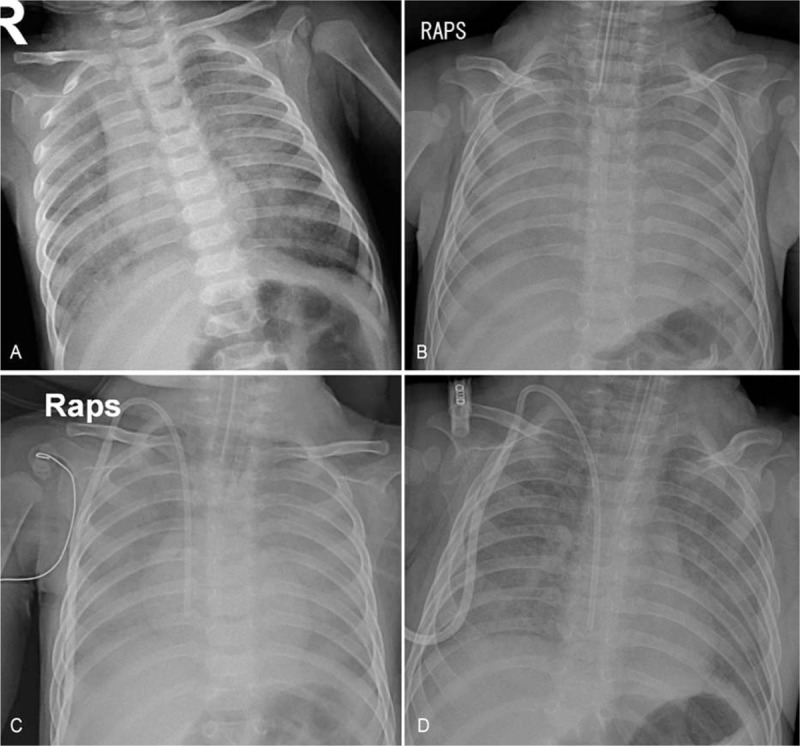

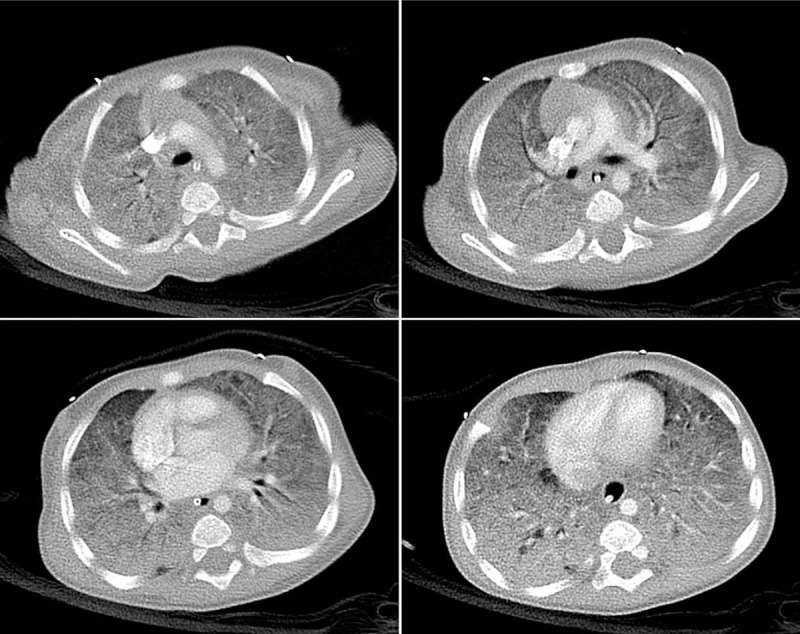

His vital signs were as follows: heart rate, 134 beats/min; respiratory rate, 49 breaths/min; and body temperature, 37.1°C. Physical examination revealed no accessory breathing sounds on chest auscultation and chest wall retractions despite tachypnea. Chest X-ray showed bilateral diffuse haziness without definite cardiomegaly (Fig. 1A). Echocardiography revealed an ejection fraction of 78.7% without any anatomical and functional abnormalities. Blood tests revealed a white blood cell count of 22,250/mm3, hemoglobin levels of 16.5 g/dL, platelet count of 536,000/mm3, and C-reactive protein levels <0.02 mg/dL without any abnormal findings in blood chemistry. We suspected interstitial lung disease of non-infectious causes or afebrile viral pneumonitis, and a multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for respiratory viruses was performed using a nasopharyngeal swab. Although there were no family and individual histories consistent with PID, a PCR test for Pneumocystis jirovecii was also performed using a nasal swab, considering interstitial pneumonitis accompanying severe hypoxemia without accessory breathing sounds. After admission, his respiratory rate increased to 60 to 90 breaths/min, and mechanical ventilator care was initiated on hospital day (HD) #2. Empirical intravenous trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX; 5 mg/kg of TMP thrice a day) treatment for possible PCP was also initiated on HD #2. Methylprednisolone (2 mg/kg twice a day) was also administered for possible interstitial pneumonitis of non-infectious causes. Chest computed tomography showed diffuse homogeneous opacity occupying alveolar spaces throughout the whole lung fields (Fig. 2). The multiplex PCR test for respiratory viruses revealed negative results for influenza virus, parainfluenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus, adenovirus, human metapneumovirus, rhinovirus, coronavirus, and human bocavirus. Bronchoscopy was performed on HD #3; however, any findings of definite airway inflammation and increased pulmonary secretion were not observed. The results of the PCR test for P. jirovecii performed on admission were reported as positive on the evening of HD #3. After then, negative culture results for bacteria, cytomegalovirus, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis were reported in bronchial washing fluid samples; cysts of P. jirovecii were observed on Gomori methenamine silver stains of bronchial washing fluids. Weaning of ventilator care and tapering of methylprednisolone doses were initiated on HDs #6 and #8, respectively. Chest X-ray findings showed improvement 2 weeks since initiating treatment (Fig. 1), and he was extubated on HD #23. Oxygen supply and methylprednisolone treatment were completed on HDs #28 and #29, respectively. A repeat PCR test for P. jirovecii showed a positive result 3 weeks after initiating TMP/SMX treatment. The PCR test showed a negative result 4 weeks after initiating treatment, and the TMP/SMX treatment was converted to prophylaxis (150 mg/m2/day of TMP, thrice a week on alternate days) on HD #29. He was discharged from the hospital on continuing TMP/SMX prophylaxis on HD #34.

Figure 1.

Chest X-rays showed (A) bilateral diffuse haziness on admission, and (B) aggravation of haziness with effacement of cardiac margin 1 week later. The diffuse haziness began to fade after 2 weeks of treatment (C), and (D) much improved 3 weeks later.

Figure 2.

Chest computed tomography showed diffuse and homogeneous opacification with air-bronchograms, which was prominent in the dependent portions of the whole lungs.

A lymphocyte subset test was performed on HD #3, and revealed the following results: CD3+ cells, 37.3%; CD4+ cells, 22.9%; CD8+ cells, 13.1%; CD19+ cells, 61.7%; and CD56+ cells, 0.6%. IgG (557 mg/dL) and IgM (74 mg/dL) levels were within normal limits; however, IgA and IgE levels could not be measured. Immunoglobulin levels measured 1 month after admission showed similar results. Genetic studies for HIGM syndrome were requested based on the repeated results of the immunologic tests. One month after discharge, a novel frameshift mutation on exon 1 of the CD40 ligand (CD40L) gene was identified using gene sequencing. The identical mutation was identified in his mother as a heterozygote, and the patient was eventually diagnosed with X-linked HIGM syndrome. TMP/SMX prophylaxis and intravenous immunoglobulin replacement therapy every 3 weeks was continued. He underwent unrelated, matched peripheral blood stem cell transplantation 8 months after the diagnosis of PCP, and 20 months have passed after transplantation without severe complications.

3. Discussion

Most cases of PCP in infancy were reported as epidemics in premature and malnourished infants around the time of World War II.[1,2] After then, in developed countries, PCP has occurred sporadically in immunocompromised children rather than epidemically in infants.[1,2] HIV infection has been regarded as an important risk factor for PCP; however, immunocompromised patients who are HIV-negative have recently occupied a greater proportion of patients with PCP than patients with HIV infection.[3] Although most immunocompromised children who are HIV-negative are those with hematologic malignancies or solid tumors and hematopoietic cell or solid-organ transplant recipients, children with PID are also at risk for PCP.[3] CD4+ T cells play an essential role in the host immune defense to P. jirovecii infection,[7] and therefore, T cell impairment rather than B cell or phagocytic impairment, is thought to be a risk factor for PCP among children with PID.[2] Severe combined immune deficiency, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, and HIGM syndrome are the most common PIDs among children with PCP.[3]

HIGM syndrome is caused by a defect in the CD40-CD40L signaling pathway.[8,9] It causes a limitation in immunoglobulin isotype switching in B cells, and therefore, normal or elevated IgM levels with low IgG, IgA, and IgE levels are observed.[8,9] Our patient showed normal IgG levels, which were thought to be due to maternal antibodies transferred across the placenta. The normal IgM levels and undetected IgA and IgE levels with an increased proportion of CD19+ cells raised the suspicion of HIGM syndrome. HIGM syndrome manifests as a T cell dysfunction rather than a B cell dysfunction, despite hypogammaglobulinemia, because most cases are caused by a mutation of the CD40L gene located at the X chromosome which encodes CD40L on the T cell surface.[8–11] Therefore, X-linked HIGM syndrome is the most frequent form of HIGM syndrome.[8,9] However, several other genes mutated and involved in CD40-CD40L signaling pathway or DNA repairing system in immunoglobulin isotype switching can cause HIGM syndrome, namely: CD40, activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AICDA), uracil-DNA glycosylase (UNG), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase catalytic delta (PIK3CD), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase regulatory subunit 1 alpha (PIK3R1), nuclear factor-kappa-B essential modulator (NEMO/IKKγ), inhibitor of kappa light chain gene enhancer in B cells, alpha (IκBα), nuclear factor kappa-B subunit 1 (NFKB1) genes participating in CD40-CD40L signaling pathway and post meiotic segregation increased 2 (PMS2), MutS Homolog 6 (MSH6), MutS Homolog 2 (MSH2), ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM), Nibrin/Nijmegen breakage syndrome 1 (NBS1/NBN) genes involved in DNA repairing system.[8,9] Most forms of these mutations are expressed through autosomal recessive inheritance, although autosomal dominant inheritance has also been reported.[8,9] Therefore, genetic evaluation should be performed in patients with HIGM syndrome phenotype to verify the exact disease mechanism and perform accurate genetic counseling.

Traditional therapies for HIGM syndrome include immunoglobulin replacement therapy, antibiotic prophylaxis for P. jirovecii infection, hygienic measures to prevent infection, and careful monitoring for other complications.[8,9] With these therapies, the median survival rate after diagnosis of HIGM syndrome was reported as 25 years.[12] However, hematopoietic cell transplantations (HCTs) have been performed in patients with HIGM syndrome to improve their prognoses since 1996.[9,12] Although the overall survival rate was not significantly improved in patients undergoing HCT compared to those receiving traditional therapies, the transplant outcome and overall survival rates tended to improve since 2006.[12] Mitsui-Sekinaka et al reported significantly higher overall survival in patients undergoing HCT since the 2000s than in those not undergoing HCT.[13] Among HCT recipients, children aged 5 years or younger showed higher survival than those aged 6 years or older.[13] Considering the improvement in HCT practice and supportive cares for HCT recipients, HCT can be regarded as a main therapy for HIGM syndrome, especially in young children.

About 90% of children with HIGM syndrome experience respiratory tract infection, and P. jirovecii has been the most common respiratory pathogen.[9–12] Especially, 43% of infants diagnosed with X-linked HIGM syndrome before 1 year of age initially presented with PCP.[11] Primary infection of P. jirovecii occurs during infancy and early childhood.[14] More than 80% of children acquire antibodies against P. jirovecii before 2 years of age, and about 20% of them seem to experience asymptomatic infection.[14] Because respiratory symptoms and signs show no significant difference between children who test positive and negative for P. jirovecii and are diagnosed with respiratory tract infection, except for the frequency of apnea,[14] clinical differentiation of P. jirovecii infection from respiratory tract infection due to other causes should be difficult. In particular, PCP is hardly suspected in children with pneumonia who have no evidence of an underlying immunocompromised state. However, pediatricians should consider that PCP can be an initial clinical presentation of PID,[4–6] and therefore, PCP should be suspected in infants with severe interstitial pneumonia accompanying normal breathing sounds when common viral and bacterial pathogens are not identified, even though the infants may show no evidence of immune deficiency. In addition, underlying PID should be evaluated in infants diagnosed with PCP using recently developed molecular genetic techniques.

In conclusion, we report an infant who presented with severe interstitial pneumonia and was diagnosed with PCP as the initial manifestation of underlying HIGM syndrome. PCP should be considered in infants presenting with severe interstitial pneumonia even in the absence of evidence of immune deficiency. PID should also be suspected in infants diagnosed with PCP to correct the underlying immunocompromised state fundamentally.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Seung Beom Han, Nack-Gyun Chung.

Data curation: Danbi Kim, Ju Ae Shin.

Supervision: Dae Chul Jeong.

Writing – original draft: Danbi Kim, Seung Beom Han.

Writing – review & editing: Nack-Gyun Chung, Dae Chul Jeong.

Seung Beom Han orcid: 0000-0002-1299-2137.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: HD = hospital day, HIGM = hyper-IgM, HIV = human immunodeficiency virus, PCP = Pneumocystis pneumonia, PCR = polymerase chain reaction, PID = primary immune deficiency, TMP/SMX = trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Goldman AS, Goldman LR, Goldman DA. What caused the epidemic of Pneumocystis pneumonia in European premature infants in the mid-20th century? Pediatrics 2005;115:e725–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Catherinot E, Lanternier F, Bougnoux ME, et al. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2010;24:107–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Saltzman RW, Albin S, Russo P, et al. Clinical conditions associated with PCP in children. Pediatr Pulmonol 2012;47:510–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Elenga N, Dulorme F, de Saint Basile G, et al. Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia revealing de novo mutation causing X-linked hyper-IgM syndrome in an infant male. The first case reported from French Guiana. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2012;34:528–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Heinold A, Hanebeck B, Daniel V, et al. Pitfalls of “hyper”-IgM syndrome: a new CD40 ligand mutation in the presence of low IgM levels. A case report and a critical review of the literature. Infection 2010;38:491–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Saulsbury FT, Bernstein MT, Winkelstein JA. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia as the presenting infection in congenital hypogammaglobulinemia. J Pediatr 1979;95:559–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Thomas CF, Jr, Limper AH. Current insights into the biology and pathogenesis of Pneumocystis pneumonia. Nat Rev Microbiol 2007;5:298–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Qamar N, Fuleihan RL. The hyper IgM syndromes. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2014;46:120–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Yazdani R, Fekrvand S, Shahkarami S, et al. The hyper IgM syndromes: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, diagnosis and management. Clin Immunol 2018;198:19–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Leven EA, Maffucci P, Ochs HD, et al. Hyper IgM syndrome: a report from the USIDNET registry. J Clin Immunol 2016;36:490–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Levy J, Espanol-Boren T, Thomas C, et al. Clinical spectrum of X-linked hyper-IgM syndrome. J Pediatr 1997;131:47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].de la Morena MT, Leonard D, Torgerson TR, et al. Long-term outcomes of 176 patients with X-linked hyper-IgM syndrome treated with or without hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017;139:1282–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Mitsui-Sekinaka K, Imai K, Sato H, et al. Clinical features and hematopoietic stem cell transplantations for CD40 ligand deficiency in Japan. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;136:1018–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Vargas SL, Hughes WT, Santolaya ME, et al. Search for primary infection by Pneumocystis carinii in a cohort of normal, healthy infants. Clin Infect Dis 2001;32:855–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]