The recent debt crisis and the subsequent compromise to raise the debt ceiling may have particular salience for health care providers over the next decade. In particular, Congress empaneled a 12-member super-committee (6 Republicans and 6 Democrats) charged with finding an additional $1.5 trillion in debt savings over a ten-year period. Given the magnitude of their charter, a logical target of reform is the Medicare program, which by itself accounts for about 15 percent of Federal spending and more of its projected growth.

To assess the potential savings from further Medicare reform, it is necessary to immerse oneself in the nuances of federal spending calculations. Medicare savings are judged against a “current law” baseline, which is intended to capture what spending would be if no legislative changes were enacted. The savings are calculated as the net difference between projected spending with new legislation and the current law baseline. Because the existing CBO baseline shows a rise in spending (about 5.5 percent per year between 2011 and 2021),1 savings can be realized without reducing total Medicare spending below current levels. All that is required is that spending grow more slowly with the new legislation.

The projections of the baseline and computation of the savings under new legislation are known as scoring, which is conducted independently by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS, Office of the Actuary) and the CBO. The super committee will use the CBO score. Scoring relies heavily on published literature, consultations with external experts, and professional judgement. It reflects the best available estimate of savings, rather than assertions that savings will occur or beliefs that new policies are worthwhile.

Given past disappointments from both public and private initiatives that seemed promising–but whose savings did not materialize–this approach seems reasonable. For example, results from the Medicare Health Support programs were disappointing and initial enthusiasm about savings associated with the Physicians Group Practice demonstration has been dampened by concerns that the findings reflect changes in coding practices as opposed to changes in delivery of care.2 Although some demonstration programs, such as the one that bundled payments for some episodes of cardiac care, have achieved savings, caution is clearly warranted.3

It is also important to note that scoring reflects federal spending, not total spending (which includes what beneficiaries pay). So initiatives that shift costs from the Medicare program to beneficiaries will be scored as generating savings–even if total health care spending, including out-of-pocket payments by Medicare beneficiaries, is unchanged.

Moreover, the current baseline–against which savings are judged–already takes into account features of current law that are assumed to keep projected spending growth well below the historic trends. Most notable of these features is the scheduled cuts to physician fees called for by the sustainable growth rate (SGR) system. This system established a target for physician spending and requires fees to be cut if the target is exceeded. Because Congress has repeatedly delayed fee cuts, the gap between the target and spending has grown, resulting in a baseline that includes about a 30 percent reduction in physician fees in 2012. CBO scoring suggests that the cost for freezing physician fees instead of cutting them would be about $300 billion over 10 years. Thus, if physician fees do not fall, proposed Medicare reforms must cut at least $300 billion over the next decade before they will even be scored as saving a dime.

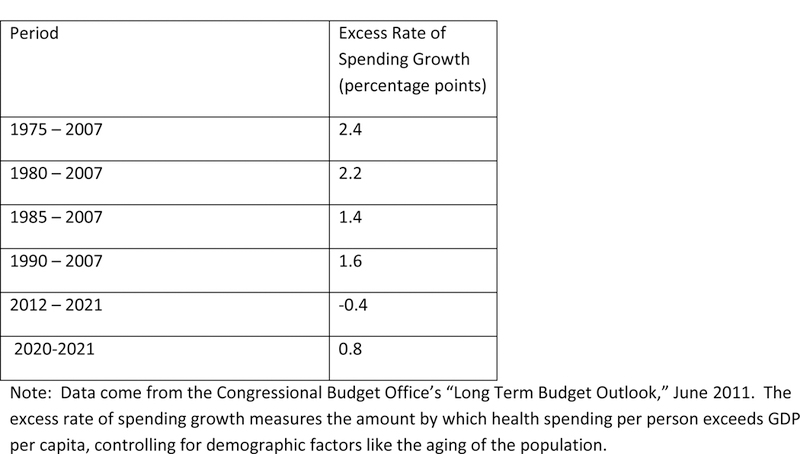

Clearly our ability to reduce spending below baseline depends on the drivers of Medicare spending growth, which include both changes in the number of Medicare beneficiaries and increases in spending per beneficiary. In the past, spending per beneficiary was the major driver of spending growth, rising much more rapidly than the number of beneficiaries. But going forward, demographics, including the influx of baby boomers into Medicare, will figure more prominently, while the role of excess spending growth -- defined as the difference in age- and sex- adjusted spending growth per beneficiary and per capita growth of the gross domestic product (GDP) -- will diminish. Because of the fee cuts expected from the SGR and Affordable Care Act, the current CBO baseline projection anticipates average per beneficiary spending growth for the next 10 years of .4 percentage points below GDP growth per capita (Figure 1). Such a low excess growth rate is unprecedented. Even in 2020, after the period of foreseen SGR cuts, excess spending growth will be well below historic average, thanks to ACA-specified cuts.

Figure 1.

Growth and projected growth in per capita Medicare spending in excess of economic growth

Certainly there are ways to reduce Medicare program spending per beneficiary. The ACA includes many provisions–including experiments with payment reform, such as accountable care organization initiatives that may eliminate some inefficiency. But some savings associated with these programs are already captured in the baseline, and evidence of sustained savings from these reforms is scant. Ultimately these programs may be successful in controlling spending, but the scoring will not reflect such savings until the evidence is stronger, and it is the scoring that matters for policy. Thus, although there are undoubtedly ways to find savings without shifting costs to beneficiaries, including further fee cuts to providers beyond those specified in the ACA, the magnitude of such savings — when officially scored — is likely to fall short of the $300 billion associated with replacing the SGR cuts with a freeze on physician fees.

An alternative is to reduce the deficit by shifting costs to beneficiaries. This can be done by converting Medicare to a premium support system, changing the eligibility requirements for Medicare (e.g., raising the eligibility age from 65 to 67), charging higher premiums (perhaps only to more affluent beneficiaries), or increasing what beneficiaries pay out of pocket for services.

Proponents of a market-based solution will note that premium support or increases in cost sharing at the point of service are not merely cost shifts. They provide incentives to beneficiaries to lower total spending. But their ability to do so is a matter of great controversy. Markets require educated, active consumers – a characterization that may not apply to enough Medicare beneficiaries. Moreover, the ability of consumers to control spending once their incentives change depends on provider market power. In many regions, providers are so consolidated that the effects of greater consumerism would probably be modest. Finally, any program that shifts costs to beneficiaries has the potential to exacerbate disparities in access to care or discourage the use of high-value services. Various stakeholders view that with varying degrees of alarm. Principles of value-based insurance design, in which copayment amounts are aligned with value (clinical benefit per dollar spent) of health care services, might mitigate that concern, but such an approach might be hard to implement in a Medicare population.

The shift in the driver of baseline spending growth away from increases in spending per beneficiary toward demographic changes has important policy implications. First, our efforts to contain total spending should focus on meeting the ambitious projections for baseline per-beneficiary spending growth, rather than aiming to derive significant savings from even lower per-beneficiary spending growth. The ACA baseline, if we can achieve it, would be an unprecedented slowdown in Medicare spending per beneficiary. And even if we succeed, total Medicare spending (program spending plus beneficiary share) as a proportion of our national economy will still rise with the influx of Baby Boomers.

Second, assuming that savings from other parts of the budget will be used to reduce the deficit, the policy question becomes how much to raise taxes to finance the demographic trend, how much to cut provider fees, and how much to shift costs (or the responsibility for controlling costs) to beneficiaries. These are not comfortable realities, but they must be addressed.

Footnotes

March 2011 Medicare Baseline. (http://www.cbo.gov/budget/factsheets/2011b/medicare.pdf.)

Report to the Congress: improving incentives in the Medicare program. Washington, DC: Medicare Payment Advisory Committee, June 2009. (http://www.medpac.gov/documents/jun09_entirereport.pdf.)

Liu CF, Subramanian S, Cromwell J. Impact of global bundled payments on hospital costs of coronary artery bypass grafting.J Health Care Finance 2001;27:39–54.

Contributor Information

Michael Chernew, Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Dana Goldman, Leonard D. Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics, University of Southern California, Los Angeles; and the RAND Corporation.

Sarah Axeen, Leonard D. Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics, University of Southern California, Los Angeles.