Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

Despite documented effectiveness of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), PrEP uptake remains low among men who have sex with men (MSM), the population bearing the highest HIV burden in the U.S.

OBJECTIVES:

To elicit MSM stakeholder preferences in order to inform program development aimed at improving uptake of PrEP.

METHODS:

554 MSM were recruited through social networking applications to complete a stated preference [choice-based conjoint (CBC)] survey. Respondents completed 14 choice tasks presenting experimentally-varied combinations of five attributes related to PrEP administration (dosing frequency, dispensing venue, prescription practices, adherence support, and costs). Latent class analysis was used to estimate the relative importance of each attribute and preferences across seven possible PrEP delivery programs.

RESULTS:

Preferences clustered into five groups. PrEP affordability was the most influential attribute across groups, followed by dosing strategy. Only one group liked daily and on-demand PrEP equally (n=74) while the other four groups disliked the on-demand intermittent option. Monthly injectable PrEP is preferred by two (n=210) out of the five groups, including young MSM. Two groups (n=267) were willing to take PrEP across all the hypothetical programs. One group (n=183) almost exclusively considered costs in their decision making. Participants in the most racially diverse among groups (n= 88) had very low level of interest in PrEP initiation.

CONCLUSION:

Our data suggest that PrEP uptake will be maximized by making daily PrEP affordable to MSM and streamlining PrEP consultation visits for young MSM. Young MSM should be prioritized for injectable PrEP when it becomes available. A successful PrEP program will spend resources on removing structural barriers to PrEP access and educating MSM of color, and will emphasize protection of privacy to maximize uptake among rural/suburban MSM.

Although men who have sex with men (MSM) comprise only 2% of the U.S. population (Purcell et al., 2012) they account for 78% of new HIV infections in men and 63% in all population groups (CDC, 2012, 2016). Biomedical HIV prevention (Truvada™) was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2012 based on the compelling data from several major studies (Baeten et al., 2012; Choopanya et al., 2013; Grant et al., 2010; Thigpen et al., 2012) and confirmed in a systematic review (Fonner et al., 2016) demonstrating that pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) reduces the risk of HIV infection by as much as 92% (Holmes, 2012).

While initial demand for PrEP following FDA approval was low, a sharp increase (as high as 332%) has since been observed in some settings (Bush, Ng, Magnuson, Piontkowsky, & Giler, 2015). Despite the increase in patient demand, the availability of PrEP has not been sufficiently scaled. According to the CDC, more that 1.25 million Americans are candidates for PrEP (Smith et al., 2015). However, only 49,158 people or about 4% of targeted population are using this prevention method (Bush et al., 2016).

Studies have sought to explain the exceedingly low PrEP uptake in the US. Misperceived low demand for PrEP (Saberi et al., 2012), poor access to health insurance (Horberg & Raymond, 2013) or a health provider (Eaton et al., 2014), lack of comfort talking to a provider about PrEP (Mayer et al., 2016), lack of provider knowledge or willingness to prescribe PrEP (Tellalian, Maznavi, Bredeek, & Hardy, 2013), and concerns about risk compensation (Golub, Kowalczyk, Weinberger, & Parsons, 2010), HIV resistance (Hurt, Eron, & Cohen, 2011), adherence (Van der Straten, Van Damme, Haberer, & Bangsberg, 2012), or costs (Juusola, Brandeau, Owens, & Bendavid, 2012) are thought to influence recommendation and use of PrEP. These studies show that while uptake can be high in settings where provider and cost factors are removed (as in demonstration projects), demand and barriers in real world settings may be more heterogeneous.

There is, thus, an urgent need to improve PrEP delivery. Programs are more likely to succeed when they consider the end users’ preferences. The objective of this study was to understand how MSM value specific attributes related to PrEP programs and to estimate preference for a range of possible delivery programs. We assume that stakeholders’ ratings of the relative attractiveness of competing attributes can inform the development of PrEP programs most likely to succeed among specific segments of MSM.

Methods

Using social networking applications, we gathered data from a convenience sample of 554 participants recruited between May – August 2015 by randomly selecting App users. Their profiles are displayed on a grid of four photos in each row. We used a randomization number chart displaying numbers from one to four to match the App’s display. A standardized script was used to message 1000 selected App users. Interested participants received a link to the survey, where eligibility was assessed and included: self-identifying as MSM, 21 years of age, self-reported HIV negative status, and no previous PrEP experience. Eligible participants used ‘click to consent’ procedure. Participants were not compensated financially. The study was approved by the Duquesne University Institutional Review Board.

A choice-based conjoint (CBC) survey to ascertain preferences for PrEP delivery programs was developed based on a review of the literature (30 studies on PrEP acceptability as identified in the review article by Young & McDaid, 2014) and in-depth discussions with multiple stakeholders. Five different PrEP delivery program attributes were included with each having three levels: 1) dosing frequency1 2) dispensing venue2 3) prescription practices3 4) adherence support4 and 5) costs.5 The survey was piloted on 10 people to ensure attribute levels were understood, relevant, and logical when combined to create a PrEP program.

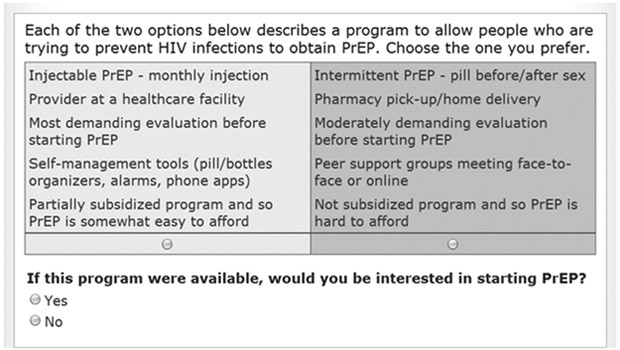

The survey was designed using Sawtooth Software, SSI Web 8.0. Preferences for hypothetical PrEP programs were solicited by asking participants to complete 14 choice tasks presenting experimentally-varied combinations of the study’s attribute levels. These CBC tasks required participants to make series of trade-offs between the levels of the study’s five attributes. Each CBC exercise included a ‘None’ option (see figure 1). The ‘None’ option is often used in market simulations to estimate the proportion of respondents that would not choose any of the simulated product concepts. Sawtooth Software’s experimental design module generated 650 different versions of the survey according to three principles: (1) each attribute level appeared only once in each choice task; (2) across choice tasks, each attribute level appeared as close to an equal number of times as possible; and (3) attribute levels were chosen independently of each other. The standard error for each level was 0.02 and the efficiencies reported were all 1.000.

Figure 1 –

Example of Choice-Based Conjoint Task

We also collected the following demographic data – age, employment, education level, Hispanic ethnicity, race, screening for depression using the PHQ-2 (Löwe, Kroenke, & Gräfe, 2005), geographical region (Midwest, Northeast, Southeast, Southwest, West), and location type (rural, suburban, urban).

Analysis

We used the Sawtooth Software Web v.8.2 to design and administer the survey and Sawtooth’s Software’s Latent Class v4 to estimate part worth utilities for each segment (Sawtooth Library). Part-worth utility is the value respondents attach to a specific level of a particular attribute. Class solutions were replicated five times from random starting seeds. A five-group solution was chosen based on Akaike’s information criterion. Utilities were entered in SAS software, version 8.2 and merged with the respondents’ characteristics. We calculated the percentage of importance that respondents assigned to each attribute by dividing the range of utilities for each attribute by the sum of the ranges and multiplying by 100 (Huber, Orme, & Miller, 2007; Orme, 2010). Relative importance reflects the influence of each attribute on subjects’ decision making.

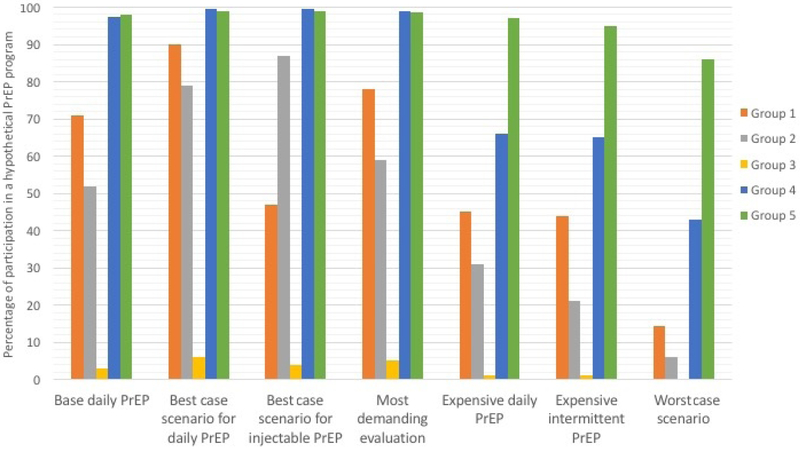

We used Sawtooth Software Market Research Tools (SMRT) to estimate preferences separately for seven hypothetical options versus no PrEP (None). The options are described in Figure 2. SMRT is a platform which enables investigators to perform simulations in order to predict preferences for specified products based on the utilities obtained during the conjoint analysis survey. In this study, treatment preferences were generated using the randomized first choice model in which utilities are summed across the levels corresponding to each option and then exponentiated and rescaled so that they sum to 100. This model assumes that subjects prefer the option with the highest utility. The randomized first choice model accounts for the error in the point estimates of the utilities as well as the variation in each respondent’s total utility for each option. This model has been shown to have better predictive ability than other models (Huber et al., 2007). Further details are available in the Sawtooth technical library (Sawtooth Library).

Figure 2 –

Preferences for possible PrEP programs

Possible PrEP Delivery Programs

1. Base daily PrEP: daily pill, prescribed by medical provider, moderately demanding evaluation, self-management tools for adherence, moderately easy to afford PrEP

2. Best Case scenario for daily PrEP: daily pill, available by pharmacy pick up, least demanding evaluation, self-management tools for adherence, easy to afford PrEP

3. Best Case scenario for injectable PrEP: monthly injections, available by pharmacy pick up, least demanding evaluation, self-management tools for adherence, easy to afford PrEP

4. Most demanding evaluation: daily pill, prescribed by medical provider, most demanding evaluation, self-management tools for adherence, easy to afford PrEP

5. Expensive daily PrEP: daily pill, available by pharmacy pick up, least demanding evaluation, self-management tools, hard to afford PrEP

6. Expensive intermittent PrEP: pill before/after sex, available by pharmacy pick up, least demanding evaluation, self-management tools for adherence, hard to afford PrEP

7. Worst Case scenario: pill before/after sex, prescribed by medical provider, most demanding evaluation, peer-support groups for adherence, hard to afford PrEP

Participants’ preferences clustered into five segments. Using this model, we were able to predict the percentage of participants in each segment who would choose hypothetical PrEP program (PrEP participation rates). This approach assumes that each participant chooses the option with the highest composite utility adjusting for both attribute and program variability.

Results

Participants

The characteristics of the 554 participants, stratified by patient segmentation group, are described in Table 1. Overall, the median age was 40 years (range = 21–53 years). Subjects were primarily white (87.4%), college-educated or higher (63.5%) and employed full-time (72.4%). The majority of respondents lived in an urban area (67%) and the geographical distribution of the sample lived in the Midwest (18.2%), Northeast (21.1%), Southeast (16.4%), Southwest (16.1%), and West (28.2%). 43% have previously heard of PrEP, and over a third (37%) of participants screened positive for depression.

Table 1–

Demographic characteristics

| Total (n=554) |

Group 1 (n=73) |

Group 2 (n=126) |

Group 3 (n=88) |

Group 4 (n=183) |

Group 5 (n=84) |

F/χ2

(p- value) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 39.9 (11.1) | 41.2 (9.9) | 38.0 (10.2) | 40.4 (11.4) | 40.2 (11.5) | 40.9 (12.4) | 0.18 |

| Employment | 0.21 | ||||||

| Full Time | 401 (72.4%) | 57 (78.1%) | 91 (72.2%) | 65 (73.9%) | 131 (71.6%) | 57 (67.9%) | |

| Part Time | 64 (11.5%) | 9 (12.3%) | 14 (11.1%) | 12 (13.6%) | 17 (9.3%) | 12 (14.3%) | |

| Retired/ on Social Security | 26 (4.7%) | 4 (2.7%) | 1 (2.4%) | 4 (4.6%) | 9 (4.9%) | 8 (9.6%) | |

| Currently a student | 69 (12.4%) | 6 (8.2%) | 30 (23.8%) | 9 (10.2%) | 13 (7.1%) | 11 (13.1%) | |

| Self- Employed | 87 (15.7%) | 10 (13.7%) | 18 (14.3%) | 13 (14.8%) | 29 (15.9%) | 17 (20.2%) | |

| Unemployed | 22 (4.0%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (4.0%) | 5 (5.7%) | 8 (4.4%) | 4 (4.8%) | |

| Education Level | 0.63 | ||||||

| High school | 33 (6%) | 3 (4.1%) | 5 (4%) | 5 (5.7%) | 13 (7.2%) | 7 (8.3%) | |

| Associate degree | 170 (30.7%) | 31 (42.5%) | 32 (25.4%) | 28 (31.8%) | 55 (30%) | 24 (28.6%) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 161 (29.1%) | 13 (17.8%) | 47 (37.3%) | 24 (27.3%) | 53 (29.0%) | 24 (28.6%) | |

| Post-graduate education | 152 (27.5%) | 19 (26%) | 32 (25.4%) | 26 (29.5%) | 52 (28.5%) | 23 (27.4%) | |

| Ph.D., J.D., M.D. | 38 (6.9%) | 7 (9.6%) | 10 (7.9%) | 5 (5.7%) | 10 (5.5%) | 6 (7.1%) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.29 | ||||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 78 (14.1%) | 10 (13.7%) | 14 (11.1%) | 29 (32.9%) | 16 (9.8%) | 9 (10.7%) | |

| Non-Hispanic or Latino | 476 (85.9%) | 63 (86.3%) | 112 (88.9%) | 59 (67.1%) | 167 (91.2%) | 75 (89.3%) | |

| Race | 0.1 | ||||||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 10 (1.8%) | 4 (5.5%) | 2 (1.6%) | 1 (1.1%) | 2 (1.1%) | 1 (1.2%) | |

| Asian | 19 (3.4%) | 1 (1.4%) | 6 (4.8%) | 2 (2.4%) | 7 (3.8%) | 3 (3.6%) | |

| Black or African American | 41 (7.4%) | 5 (6.9%) | 10 (7.9%) | 13 (14.7%) | 9 (7.1%) | 4 (4.8%) | |

| White | 484 (87.4%) | 64 (86.3%) | 109 (85.7%) | 72 (81.8%) | 162 (88.0%) | 77 (90.5%) | |

| Importance of religion | 0.95 | ||||||

| High | 65 (11.8%) | 8 (11%) | 13 (10.3%) | 11 (12.5%) | 24 (13.2%) | 10 (12.0%) | |

| Moderate | 118 (21.1%) | 17 (23.3%) | 27 (21.5%) | 20 (22.7%) | 37 (20.2%) | 16 (19%) | |

| Low | 158 (28.6%) | 24 (32.9%) | 36 (28.6%) | 29 (33%) | 47 (25.7%) | 22 (26.2%) | |

| None | 213 (38.5%) | 24 (32.9%) | 50 (39.7%) | 28 (31.8%) | 75 (41.0%) | 36 (42.9%) | |

| Depression | 0.68 | ||||||

| PHQ-2 composite | 208 (37.5%) | 27 (36.9%) | 42 (33.3%) | 34 (38.6%) | 69 (37.7%) | 36 (42.8%) | |

| Region | 0.18 | ||||||

| Midwest | 101 (18.2%) | 14 (19.2%) | 22 (17.5%) | 14 (15.9%) | 38 (20.8%) | 13 (15.5%) | |

| Northeast | 117 (21.1%) | 16 (21.9%) | 21 (16.6%) | 26 (29.6%) | 43 (23.5%) | 12 (14.3%) | |

| Southeast | 91 (16.4%) | 10 (13.7%) | 22 (17.5%) | 10 (11.4%) | 24 (13.7%) | 25 (29.8%) | |

| Southwest | 89 (16.1%) | 10 (13.7%) | 21 (16.6%) | 16 (18.2%) | 32 (16.9%) | 12 (14.3%) | |

| West | 156 (28.2%) | 23 (31.5%) | 40 (31.8%) | 22 (25.0%) | 46 (25.1%) | 22 (26.2%) | |

| Location | 0.55 | ||||||

| Rural | 22 (3.9%) | 1 (1.4%) | 6 (4.8%) | 4 (4.5%) | 7 (3.8%) | 4 (4.9%) | |

| Suburban | 161 (29.1%) | 17 (23.3%) | 30 (23.8%) | 19 (21.6%) | 59 (32.2%) | 36 (42.8%) | |

| Urban | 371 (67.0%) | 55 (75.3%) | 90 (71.4%) | 65 (73.9%) | 117 (63.9%) | 44 (52.3%) |

There were no statistically significant differences between demographic characteristic of groups. It is worth mentioning that MSM in Group 3 were more likely to identify as Hispanic (32.9%) or African American (14.7%). MSM in Group 2 were more likely to be students (quarter of the group membership and almost half of the total number of student participants). Finally, almost half of the MSM in Group 5 (47.7%) lived in rural or suburban areas.

Relative Importance and Part-Worth Utilities

Subjects’ relative importance of the attributes and part-worth utilities of each level for each attribute are shown in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. Cost was the most important attribute in each of the five groups. Group 1 members (n=73, 13.4%), were strongly and equally influenced by two factors – affordability of PrEP and dosing frequency. Individuals in this group had equal preference for either daily pill or on-demand intermittent pills while strongly opposing the option of long-lasting injectable PrEP (Table 3). Costs and dosing frequency were also the two most important attributes for participants in Group 2 (n = 126, 22.9%), the second largest segment. In contrast to members of Group 1, however, cost was twice as important as dosing frequency, and members of Group 2 preferred long-lasting injectable PrEP. Subjects in Group 3 (n= 88, 15.8%), were somewhat less impacted by dosing frequency and more influenced by cost, compared to Groups 1 and 2. Subjects in Group 4 (n= 183, 31.7%), the largest segment, almost exclusively considered costs in their decision making. Finally, members of Group 5 (n= 84, 16.2%), while also most impacted by cost, were more likely to consider the type of dispensing venue and adherence support compared to the other groups.

Table 2 –

Relative importance of each aspect of an optimized PrEP Program for Each Segmentation Group

| Characteristic of the PrEP delivery program |

Total | Segmentation Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 (n=73) |

Group 2 (n=126) |

Group 3 (n=88) |

Group 4 (n=183) |

Group 5 (n=84) |

||

| Dosing frequency (%) | 17 | 36.5 | 22.6 | 18.2 | 1.8 | 23 |

| Dispensing Venue (%) | 8 | 7.7 | 8.4 | 4.9 | 5.3 | 19.4 |

| Initial Visit (%) | 9 | 6.8 | 12.5 | 5.1 | 6.4 | 10.6 |

| Adherence Support (%) | 10 | 10.5 | 9.4 | 11.8 | 8.4 | 15.2 |

| Affordability (%) | 56 | 38.5 | 47.1 | 60 | 78.1 | 31.8 |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

Table 3 –

Part Worth Utilities (zero-centered values)*

| Group 1 (n=73) |

Group 2 (n=126) |

Group 3 (n=88) |

Group 4 (n=183) |

Group 5 (n=84) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dosing Frequency | |||||

| Daily PrEP - pill once a day | 65.84 | −2.27 | 45.78 | 0.78 | 35.07 |

| Intermittent PrEP – pill before/after sex | 63.55 | −59.82 | −1.35 | −1.15 | −81.84 |

| Injectable PrEP - monthly injection | −129.4 | 62.09 | −44.42 | 0.37 | 46.76 |

| Dispensing Venue | |||||

| Provider at a healthcare facility | −15.36 | −14.09 | −13.65 | −16.07 | −18.11 |

| Agency that works in LGBT health/HIV prevention | −6.45 | −12.97 | 3.36 | 7.59 | −45.61 |

| Pharmacy pick-up/home delivery | 21.82 | 27.07 | 10.29 | 8.48 | 63.73 |

| Initial Visit | |||||

| Least demanding evaluation before starting PrEP | 14.38 | 28.85 | 15.09 | 2.48 | 33.11 |

| Moderately demanding evaluation before starting PrEP | 3.01 | 5.51 | −5.93 | 14.77 | −10.29 |

| Most demanding evaluation before starting PrEP | −17.39 | −34.35 | −9.15 | −17.26 | −22.81 |

| Adherence Support | |||||

| Self-management tools (pill/bottles organizers, alarms, phone apps) | 27.72 | 20.02 | 13.71 | 17.93 | 15.11 |

| Peer support groups meeting face-to-face or online | −24.17 | −25.12 | −36.47 | −22.05 | −48.33 |

| Text messages or phone reminders from your provider | −3.55 | 5.09 | 22.75 | 4.57 | 33.23 |

| Affordability | |||||

| Well subsidized program and so PrEP is easy to afford | 78.02 | 100.22 | 129.18 | 175.29 | 40.24 |

| Partially subsidized program and so PrEP is somewhat easy to afford | 27.83 | 28.09 | 43.98 | 50.44 | 42.15 |

| Not subsidized program and so PrEP is hard to afford | −105.85 | −128.32 | −173.17 | −225.74 | −82.39 |

| Not willing to take PrEP under any scenario | 43.79 | 39.73 | 719.75 | −249.6 | −724.07 |

Legend: LGBT: lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender; PrEP: pre-exposure prophylaxis

Interpretation: negative values imply negative preferences for the program attribute and the magnitude of the preference is associated with the strength

Preferences for PrEP Programs

In addition to making a set of trade-offs between two hypothetical programs, each participant had to answer yes/no to the following question: “If this program were available, would you be interested in starting PrEP?” (Figure 1). Members of Groups 1 and 2 chose ‘None’ for 56% and 51% of the choice tasks, respectively. Subjects in Group 3 chose the ‘None’ option 91% of the time, indicating their lack of interest in PrEP regardless of the program presented. Subjects in Group 4 chose ‘None’ 29% of the time and those in Group 5 chose ‘None’ 7% of the time indicating that members of both of these groups were highly interested in PrEP and that members of Group 5 would opt for PrEP regardless of the specific characteristics of the program. Preferences for PrEP across possible programs are illustrated in Figure 2. Preferences reflect interest in PrEP described in the preceding paragraph with members of Groups 1 and 2 being more sensitive to changes in programs, compared to those in Groups 4 and 5, most of whom were willing to take PrEP under all but the Worst-Case scenario. In the Base Case, i.e. the scenario that most resembles the current state of PrEP delivery6, the overall uptake rate was 69%. As expected, the Best-Case Pill program maximizes the number of subjects willing to start PrEP. Under this scenario7, a larger number of subjects in Groups 1 and 2 are willing to use PrEP compared to the current programs. Offering PrEP by injection attracts a small increase in subjects from Group 2 only (Best Case Injectable). Expensive, non-subsidized programs, result in a substantial decrease in the numbers of subjects willing to take PrEP across Groups 2 through 4 and a small decrease in members of Group 5. Enabling PrEP to be used on-demand (Expensive Intermittent Pill) did not offset the barrier imposed by cost. Requiring visits to a provider and a demanding a thorough evaluation (Demanding Evaluation) prior to starting PrEP decreased willingness among members in Groups 1 and 2 despite the program being well-subsidized. The overall uptake rate under the Worst-Case scenario for daily PrEP8 drops to 30%. Under these conditions, a majority willing to use PrEP are found in Group 5 only.

Discussion

Overall, we found high levels of interest in PrEP by MSM, with 79% of respondents being willing to start PrEP under the Best-Case scenario.9 Our data suggest that the most important factor to consider when designing PrEP programs is out-of-pocket costs. While subjects varied in the importance they attached to other attributes, affordability was the most influential programmatic attribute across all five groups.

While the high cost of PrEP is covered by Medicaid and most private insurances, one may still expect monthly co-payments as high as 20–50% of the total cost (potentially augmented by the Gilead assistance program) (Smith, Van Handel, & Huggins, 2017). Patients’ preference for PrEP decreases significantly with the increase in cost of Truvada from 79% when PrEP is easy to afford, to 69% when PrEP is moderately affordable, to 50% when PrEP is expensive. Young MSM (Group 2), the demographic with the greatest percentage increase (26%) in HIV incidence, are very sensitive to changes in PrEP cost. Their participation rates drop from 79% to 52% when PrEP becomes moderately affordable, to 31% when PrEP is expensive. Even when PrEP is expensive, however, half of total MSM participating in this study remain interested and would initiate it. While on-demand PrEP may appear as the best strategy when finances are burdensome, its uptake is not higher compared to the daily PrEP option (46% vs 50%).

On-demand intermittent PrEP reduces HIV incidence by 86% yet our data suggest that daily PrEP is the dosing strategy preferred by most MSM. Only one group (Group 1) had an equal preference for daily or on-demand intermittent PrEP. All other groups either slightly (Group 3 and 4) or very strongly disliked (Group 2 and 5) on-demand relative to daily PrEP. These preferences are in line with the literature on choices between daily and on-demand dosing for other types of treatment such as tadalafil to treat erectile dysfunction (Costa, Grivel, & Gehchan, 2009). This preference remains constant for choices between daily and injectable PrEP. Under optimal conditions, a slightly higher number of participants are willing to use daily PrEP, compared to lower uptake rates for monthly injectable PrEP. The lower participation in injectable PrEP is best explained by loss of members from Group 1 who strongly dislike injectable PrEP, compensated by moderate gains of members from Groups 2 and 5 who have a strong preference for monthly injectable dosing. Those preferring injectable PrEP (Groups 2 and 5) are overall younger and better educated. This pattern is similar to that from the contraception literature where younger women preferred injectable, long-acting contraception over daily pills (Kavanaugh, Jerman, & Finer, 2015).

MSM in Group 5 were highly interested in PrEP. However, they preferred more comprehensive PrEP services, including more privacy in adherence approaches and interaction with clinicians. In order to understand these preferences, we looked at the demographic characteristics of this group. While not statistically significant, it is worth noting that one third of this group lived in Southeast and almost half of the members lived and rural and suburban areas. Rural and suburban MSM often have to deal with challenges that complicate implementation of PrEP programs like limited access to healthcare services, disclosure concerns common in close-knit communities, and stigma resultant from having to discuss sexuality (CDC, 2016). Our results may suggest that ensuring privacy in PrEP access and use should be essential elements of a PrEP program targeting suburban and rural areas. Study participants living in these areas strongly prefer to receive PrEP from a pharmacy and receive phone or text reminders from a provider to maintain adherence.

Group 3 members had very low interest in PrEP across all scenarios, suggesting that members of this Group are not willing to use PrEP for reasons unrelated to access. While race and ethnicity were not statistically significant across all groups, it is important to note that Group 3 was more racially diverse than any other group. One third of this group identified themselves as Hispanic and 15% of the group were African American. These are the demographics where HIV infections are on the rise. While it is difficult to define one reason why these groups are unwilling to consider PrEP for prevention, it is likely to be at least in part due to stigma, mistrust, lack of access, and lack of awareness (Khanna et al., 2016). Our research points to the importance of further outreach and education about PrEP for African-American and Latino men.

Our data suggest that PrEP programs likely to have the biggest impact are ones that are perceived to be affordable. Uptake can be further increased by continuing to promote daily PrEP, facilitating PrEP access and delivery, and reducing burdensome clinical visits, especially in younger MSM. Studies suggest that long-acting injectable PrEP will be preferred by young MSM (Meyers et al., 2014; Parsons, Rendina, Whitfield, & Grov, 2016). While the results of our study cannot be conclusive in this regard, we noted the tendency among younger participants (group 2) to prefer injectable PrEP. Therefore, this population can be prioritized for long-acting injectable PrEP when it becomes available. An effective PrEP program will spend resources on removing structural barriers in access and educating racial/ethnic minority MSM about PrEP, will offer a variety of adherence promotion strategies to urban MSM, and provide adherence support in form of text messages or phone calls to minority populations and MSM living in rural areas. Programs for MSM living in rural and suburban areas should also emphasize protection of privacy to maximize uptake.

Limitations:

First, as with other studies using simulated scenarios, stated preferences may not reflect the actual decision-making process in a real-world setting. Second, the sampling method employed in our study may have led to the possible introduction of sampling bias. Third, because of the variability in the impact of specific cost estimates (for instance, a $25 copay for some is easy to afford, whereas for others it may be prohibitive), we opted to use levels of cost that would be meaningful across a heterogeneous population. The levels were standardized by providing a specific definition for each level: “Easily affordable means that there is no need to make changes in your budget to pay for your monthly dose of PrEP. Moderately affordable means that some changes in your budget are needed to be able to pay for your monthly dose of PrEP. Hard to afford means that significant changes in your budget are needed to be able to pay for your monthly dose of PrEP.” Fourth, we chose to omit efficacy and safety-related attributes of PrEP, focusing mostly on program delivery. Fifth, as the research on long-lasting injectable PrEP is still ongoing, the specifications of injectable PrEP are not yet available and may range from injections every month to 3 months. The shorter injection time may impact acceptability. Finally, this study has been conducted in 2015. PrEP related knowledge, public perception, and preferences may have changed since that time.

This study had two goals – to determine a combination of PrEP program features that will optimize uptake among MSM and to describe segments of MSM population with homogeneous preferences. We found that uptake most likely to be successful when PrEP is affordable, when recommendation for dosing strategy are presented as a continuum of flexible and changeable choices over time, when users can choose their preferred types of adherence support, and when the stress of the PrEP initiation visit is accounted for and addressed by a provider. Most importantly, the results highlight the need to ensure that PrEP is “easily affordable”.

*.

Financial support for this study was provided in part by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (K24 DA017072, Altice) and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (AR060231–05, Fraenkel). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The funding agreement ensured the authors’ independence in designing the study, interpreting the data, writing, and publishing the report.

Footnotes

pill taken once a day, intermittent PrEP, long-lasting injectable PrEP

provider at a healthcare facility/sexually transmitted infections (STI) clinic, agency that works in lesbian-gay-bisexual-transgendered (LGBT) health/HIV prevention, pharmacy pick-up/home delivery

less demanding evaluation defined as HIV test + kidney function test, moderately demanding evaluation defined as HIV test + kidney function test + full STI panel, most demanding evaluation defined as HIV test + kidney function test + full STI panel + safer sex counseling

self-management tools, peer support groups, text messages/interactive voice response messages

PrEP program is well-subsidized and easily affordable, partially subsidized and moderately affordable, not subsidized and difficult to afford

Daily PrEP, provider at a healthcare facility, moderately demanding evaluation, self-management tools, moderately easy to afford PrEP.

Pill once a day picked up from a pharmacy, least demanding evaluation, self-management adherence tools, easy to afford.

Pill once a day provided by a doctor, most-demanding evaluation, peer support to facilitate adherence, and difficult to afford PrEP.

Affordable daily pill available within a pharmacy, with minimal testing and use of self-management adherence tools

Contributor Information

Alex Dubov, Yale Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS, 135 College Street, Suite 200, New Haven, CT, 06510-2483, Phone: (404)914-7231, oleksandr.dubov@yale.edu.

Adedotun Ogunbajo, Yale University School of Public Health, Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, 60 College Street, New Haven, CT 06510, adedotun.ogunbajo@yale.edu.

Frederick L. Altice, Director of Clinical and Community Research, Yale University School of Medicine, Section of Infectious Diseases, AIDS Program, 135 College Street, Suite 323, New Haven, CT 06510-2283, Phone: (203)737-2883, frederick.altice@yale.edu.

Liana Fraenkel, Yale University School of Medicine, Section of Rheumatology, PO Box 208031, 300 Cedar Street, TAC Bldg., New Haven, CT 06520-8031, Phone: (203) 932-5711 ×5914, liana.fraenkel@yale.edu.

Bibliography

- Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, Mugo NR, Campbell JD, Wangisi J, ... & Ronald A (2012). Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. New England Journal of Medicine, 367(5), 399–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush S, Magnuson D, Rawlings MK, Hawkins T, McCallister S, & Mera Giler R (2016). Racial characteristics of FTC/TDF for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) users in the US. ASM Microbe/ICAAC. [Google Scholar]

- Bush S, Bush S, Ng L, Magnuson D, Piontkowsky D, & Mera Giler R (2015, June). Significant uptake of Truvada for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) utilization in the US in late 2014–1Q 2015. In IAPAC Treatment, Prevention, and Adherence Conference (pp. 28–30). [Google Scholar]

- Choopanya K, Martin M, Suntharasamai P, Sangkum U, Mock PA, Leethochawalit M, ... & Chuachoowong R (2013). Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV infection in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand (the Bangkok Tenofovir Study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. The Lancet, 381(9883), 2083–2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2012). Vital signs: HIV infection, testing, and risk behaviors among youths-United States. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 61(47), 971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2016). HIV Surveillance Report: Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2011. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2016, March). Lifetime risk of HIV diagnosis in the United States. In 2016 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (Vol. 7). [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2016). HIV in the Southern United States. Issue Brief. [Google Scholar]

- Costa P, Grivel T, & Gehchan N (2009). Tadalafil once daily in the management of erectile dysfunction: patient and partner perspectives. Patient preference and adherence, 3, 105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton LA, Driffin DD, Smith H, Conway-Washington C, White D, & Cherry C (2014). Psychosocial factors related to willingness to use pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention among Black men who have sex with men attending a community event. Sexual health, 11(3), 244–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonner VA, Dalglish SL, Kennedy CE, Baggaley R, O’Reilly KR, Koechlin FM, Rodolph M, Hodges-Mameletzis I, … Grant RM (2016). Effectiveness and safety of oral HIV preexposure prophylaxis for all populations. AIDS (London, England), 30(12), 1973–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub SA, Kowalczyk W, Weinberger CL, & Parsons JT (2010). Preexposure prophylaxis and predicted condom use among high-risk men who have sex with men. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999), 54(5), 548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu AY, Vargas L, ... & Montoya-Herrera O (2010). Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. New England Journal of Medicine, 363(27), 2587–2599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes D (2012). FDA paves the way for pre-exposure HIV prophylaxis. The Lancet, 380(9839), 325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horberg M, & Raymond B (2013). Financial policy issues for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis: cost and access to insurance. American journal of preventive medicine, 44(1), S125–S128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber J, Orme B, & Miller R (2007). The value of choice simulators Conjoint measurement. Springer, New York, 347–362. [Google Scholar]

- Hurt CB, Eron JJ Jr, & Cohen MS (2011). Pre-exposure prophylaxis and antiretroviral resistance: HIV prevention at a cost? Clinical Infectious Diseases, 53(12), 1265–1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juusola JL, Brandeau ML, Owens DK, & Bendavid E (2012). The cost-effectiveness of preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention in the United States in men who have sex with men. Annals of internal medicine, 156(8), 541–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanaugh ML, Jerman J, & Finer LB (2015). Changes in use of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods among US women, 2009–2012. Obstetrics and gynecology, 126(5), 917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna AS, Michaels S, Skaathun B, Morgan E, Green K, Young L, & Schneider JA (2016). Preexposure prophylaxis awareness and use in a population-based sample of young black men who have sex with men. JAMA internal medicine, 176(1), 136–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawtooth Library. Retrieved from https://www.sawtoothsoftware.com/help/issues/ssiweb/online_help/index.html?hid_smrt_randomizedfirstchoice.htm

- Löwe B, Kroenke K, & Gräfe K (2005). Detecting and monitoring depression with a two-item questionnaire (PHQ-2). Journal of psychosomatic research, 58(2), 163–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer KH, Oldenburg CE, Novak DS, Elsesser SA, Krakower DS, & Mimiaga MJ (2016). Early adopters: Correlates of HIV chemoprophylaxis use in recent online samples of US men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior, 20(7), 1489–1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers K, Rodriguez K, Moeller RW, Gratch I, Markowitz M, & Halkitis PN (2014). High interest in a long-acting injectable formulation of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV in young men who have sex with men in NYC: a P18 cohort substudy. PloS One, 9(12), e114700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orme BK (2010). Getting started with conjoint analysis: strategies for product design and pricing research: Research Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, Rendina HJ, Whitfield TH, & Grov C (2016). Familiarity with and preferences for oral and long-acting injectable HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in a national sample of gay and bisexual men in the US. AIDS and Behavior, 20(7), 1390–1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell DW, Johnson CH, Lansky A, Prejean J, Stein R, Denning P, . . . Crepaz N (2012). Suppl 1: Estimating the population size of men who have sex with men in the United States to obtain HIV and syphilis rates. The open AIDS journal, 6, 98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saberi P, Gamarel KE, Neilands TB, Comfort M, Sheon N, Darbes LA, & Johnson MO (2012). Ambiguity, ambivalence, and apprehensions of taking HIV-1 pre-exposure prophylaxis among male couples in San Francisco: a mixed methods study. PloS one, 7(11), e50061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DK, Van Handel M, Wolitski RJ, Stryker JE, Hall HI, Prejean J, . . . Valleroy LA (2015). Vital signs: estimated percentages and numbers of adults with indications for preexposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV acquisition—United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 64(46), 1291–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DK, Van Handel M, & Huggins R (2017). Estimated coverage to address financial barriers to HIV preexposure prophylaxis among persons with indications for its use, United States, 2015. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 76(5), 465–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tellalian D, Maznavi K, Bredeek UF, & Hardy WD (2013). Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV infection: results of a survey of HIV healthcare providers evaluating their knowledge, attitudes, and prescribing practices. AIDS patient care and STDs, 27(10), 553–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, Smith DK, Rose CE, Segolodi TM, . . . Chillag KL (2012). Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana. New England Journal of Medicine, 367(5), 423–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Straten A, Van Damme L, Haberer JE, & Bangsberg DR (2012). Unraveling the divergent results of pre-exposure prophylaxis trials for HIV prevention. Aids, 26(7), F13–F19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young I, & McDaid L (2014). How acceptable are antiretrovirals for the prevention of sexually transmitted HIV?: A review of research on the acceptability of oral pre-exposure prophylaxis and treatment as prevention. AIDS and Behavior, 18(2), 195–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]