Abstract

Purpose:

The legal landscape of cannabis availability and use in the U.S. is rapidly changing. As the heterogeneity of cannabis products and methods of use increases, more information is needed on how these changes affect use, especially in vulnerable populations such as youth.

Methods:

A national sample of adolescents aged 14–18 years (N=2630) were recruited online through advertisements displayed on Facebook and Instagram to complete a survey on cannabis. The survey assessed patterns of edible use, vaping, and smoking cannabis, and the associations among these administration routes and use of other substances.

Results:

The most frequent and consistent route of cannabis use was smoking (99% lifetime), with substantial numbers reporting vaping (44% lifetime) and edible use (61% lifetime). The majority of those who had experimented with multiple routes of cannabis administration continued to prefer smoking, and the most common pattern of initiation was smoking, followed by edibles and then vaping. In addition to cannabis use, adolescents reported high rates of nicotine use and substantial use of other substances. Adolescents who used more cannabis administration routes tended to also report higher frequency of other substances tried.

Conclusions:

Additional work is needed to determine whether the observed adolescent cannabis administration patterns are similar across different samples and sampling methods as well as how these trends change over time with extended exposure to new products and methods. The combined knowledge gained via diverse sampling strategies will have important implications for the development of regulatory policy and prevention and intervention efforts.

Keywords: cannabis, marijuana, administration methods, adolescent, youth, smoking, vaping, edibles, nicotine, tobacco

1. Introduction

Cannabis use in the United States (U.S.), particularly among youth, is rapidly changing due to a confluence of factors. More states are legalizing medical and recreational use, the potency of cannabis continues to increase, and the perceptions of harmfulness regarding cannabis use are decreasing among adult and youth populations 1–4 Novel devices and products used to administer cannabis, such as vaporizers and edibles, are also becoming increasingly available as dispensaries expand in legalized states5. Vaporizing (“vaping”) cannabis appears to be gaining popularity, as is vaping of other psychoactive substances, such as nicotine, which appears driven in part by consumer perception of vaping as a healthier, more discreet administration method compared to the traditional route of smoking 6–9. The implications of this evolving landscape of cannabis administration methods and products are relatively unknown, especially among youth and other vulnerable populations.

National surveillance systems, such as the Youth Risk Behavior Survey, have not traditionally assessed specific questions pertaining to administration of youth cannabis use, but have focused more on prospectively tracking frequency of general use. Just in 2017, the national surveillance system, Monitoring the Future Survey, expanded to incorporate a section on vaping, including separate prevalence questions on substances vaped (i.e., vaping cannabis, vaping flavors, and vaping nicotine)10. Reports in years past11 only asked about e-cigarette and vaporizer general use, and one question on the last substance vaped. Importantly, the cannabis section in the most recent report still focused on general frequency of use (any method), not including questions on a wider variety of administration methods, such as cannabis edibles.

Similarly, while not the standard, some state surveillance surveys have begun to collect data on more nuanced cannabis-related questions. The Healthy Kids Colorado Survey in 2015, for example, assessed such trends by asking how youth typically administer and obtain cannabis, in addition to the traditional frequency of use questions.12 The California Healthy Kids Survey just added questions on eating, drinking, and vaping cannabis in 2017–2018 (in addition to smoking)13. One pattern observed from the Healthy Kids Survey was that California youth who reported lifetime use of cannabis edibles were heavier overall cannabis users compared to adolescents who had never used cannabis edibles (among lifetime cannabis user)14. Other studies have leveraged social media platforms (e.g., Twitter, Facebook, Instagram) and focus groups to report on such topics as the profiles of adolescents that use cannabis edibles15, content of edible use tweets on Twitter16, and the relation between legal cannabis law provisions and adolescents’ use of multiple cannabis administration routes (i.e., edible use and vaping)17.

At this sensitive juncture of policy changes on cannabis legalization in the U.S., it is critical for policy makers to look to data on specific use patterns to inform regulatory efforts that aim to mitigate potential harms to youth and other vulnerable populations. Indeed, information on how and in what contexts youth administer cannabis is essential for the development of effective youth preventive and treatment programs for cannabis use. Previous reports have primarily focused on broad use patterns related to cannabis and thus have lacked specificity and investigation of nuanced trends. The goal of this study was to leverage social-media platforms (i.e., Facebook and Instagram) to assess a large, national sample of adolescents who had used cannabis to ask more fine-grained questions about cannabis use patterns 17–19 The survey assessed (1) rates, patterns, and characteristics related to cannabis administration methods of smoking, vaping, and edible use, (2) age of initiation and trends in other substance use, and (3) vaping typology and trends.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Participants and Recruitment

Adolescent cannabis users from all 50 U.S. states completed an online survey distributed through paid advertisements18 displayed on Facebook and Instagram from April 29th to May 18th, 201620. To target cannabis using adolescents, advertisements containing cannabis-related imagery and language were displayed to youth aged 14–18 years1 who had endorsed cannabis-related interests on their Facebook profile (e.g., High Times Magazine, NORML, etc.). Samples generated via Facebook advertising may be best viewed as targeted, non-probabilistic samples. Much in the same way that targeted samples from substance use disorder treatment centers provide important insights about youths’ behaviors, the goal of Facebook advertising is to collect samples that overrepresent those youth who are most at risk (i.e., those youth consuming cannabis frequently; see20 for an overview paper on this type of sampling method). A hyperlink embedded in the ad directed adolescents to the informed consent page hosted by a secure online data-acquisition platform (Qualtrics, Provo, UT). Youth who endorsed lifetime cannabis use were eligible for the study. No compensation was provided. Parental consent was waived due to the anonymity of the survey (no IP addresses/identifiable information were collected). Qualtrics data quality functions prevented multiple responses from a single individual, ensured that responses came from people and not internet bots, and excluded adolescents over 18 and under 14 years. Data quality checks also excluded participants who did not provide their education level and lifetime cannabis use. The distribution across the 50 states of the obtained sample closely corresponded to that of the total U.S. population distribution (Pearson’s r = 0.82)21. The survey required all items to be answered. Study methods and separate findings from a larger dataset (related to associations between legal cannabis laws and patterns of youth cannabis use) have previously been published17. All procedures were approved by Dartmouth College’s Institutional Review Board.

2.2. Survey and Analyses

The survey consisted of cannabis-related items that assessed use history, current use patterns, and reasons and preferences for each administration method with a particular focus on the route of vaping (see Appendix A for survey instrument). For example, adolescents were asked if they had ever used marijuana (pot, weed, herb) and given the reminder that marijuana could include things such as leaf and buds, and also extracts and concentrates. Specific questions about vaping included type of vaporizer used most frequently to vape marijuana, whether they owned or bought a vaporizer, and types of marijuana vaped. A limited set of questions targeted socio-demographic characteristics and use of other substances. The survey was designed by a team of scientists with expertise in cannabis and nicotine use. The final questionnaire was a product of several rounds of internal review and recommendations, as well as revisions prompted by feedback from practice versions

Descriptive statistics illustrated prevalence and frequency of cannabis use, administration methods used, types of vaporizer used, types of substances vaped, age of first use among the varying methods, etc. A test of analysis of variance and posthoc follow-up tests were computed to compare lifetime use of nine other drug classes (sum score ranging from 1–9; see Table 1 for list of drug classes) between the three groups of adolescents who had ever used one, two, or three methods of cannabis administration (sum score ranging from 1–3).

Table 1:

Participant Characteristics

| Total (n = 2630) | ||

|---|---|---|

| M (SD) or % | n | |

| Demographic Characteristics | ||

| Age | 16.36 (1.1) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 45.7 | 1201 |

| Female | 50.8 | 1337 |

| Transgender | 1.9 | 49 |

| Other | 1.6 | 43 |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian | 78.6 | 2067 |

| African-American | 3.4 | 89 |

| Hispanic | 13.5 | 355 |

| Othera | 4.5 | 119 |

| Education | ||

| 6–8th Grades | 11.3 | 296 |

| 9–10th Grades | 48.7 | 1280 |

| 11th–12th Grades | 35.6 | 936 |

| Started College | 4.5 | 118 |

| Substance Use | ||

| Cigarette Use | ||

| Lifetime Use | 72.7 | 1912 |

| Use in the Past 30 Daysb | 57.5 | 1100 |

| Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems Use | ||

| Lifetime Use | 70.6 | 1858 |

| Use in the Past 30 Daysc | 50.3 | 934 |

| Lifetime Other Drug Use | ||

| Alcohol | 90.6 | 2384 |

| Pain Killers (Vicodin, OxyContin, Hydrocodone, Percocet, Dilaudid, Heroin) | 39.2 | 1030 |

| “Study” Drugs (Adderall, Ritalin) | 37.5 | 985 |

| Hallucinogens (Shrooms, LSD, DMT) | 31.9 | 839 |

| Downers (Bennies, Valium, Klonipin, Ativan, Xanax) | 31.2 | 820 |

| Uppers (Cocaine, Amphetamine, Methamphetamine) | 19.8 | 522 |

| Molly or Ecstasy | 15.9 | 419 |

| Inhalants (Gasoline, Nitrous Oxide, Poppers, Whippets) | 12.7 | 334 |

Note:

This group represents adolescents who identified as American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander.

Among those adolescents who reported smoking cigarettes at least once in the past 30 days.

Among those adolescents who reported use of electronic nicotine delivery systems at least once in the past 30 days.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

The ads were displayed on 126,945 individuals’ digital devices, 5,480 (4%) clicked the ad and were directed to the survey. Thirty-three adolescents who did not consent and 210 who were not 14–18 years or provide their education level were excluded. Of those eligible, 3035 (58%) completed the entire survey and passed the data quality checks. Of those, 405 reported no lifetime use of cannabis. The final sample for the present analyses was therefore n=2,630. Table 1 provides demographics and substance use frequencies. These youths had a mean age of 16.4 (SD = 1.1), were in grade 6 through first year of college, were 51% female, and 79% Caucasian.

3.2. Trends in Methods of Cannabis Administration

3.2.1. Patterns of smoking, vaping, and edible use.

The majority of the sample reported lifetime cannabis use of more than 365 days (41%) or between 101–365 days (22%), with the remainder reporting 31–100 days (13%) and 1–30 days (22%). Almost all (99%) endorsed ever smoking cannabis (only 14 reported never smoking), 61% reported lifetime use of edibles, and 44% reported ever vaping cannabis.

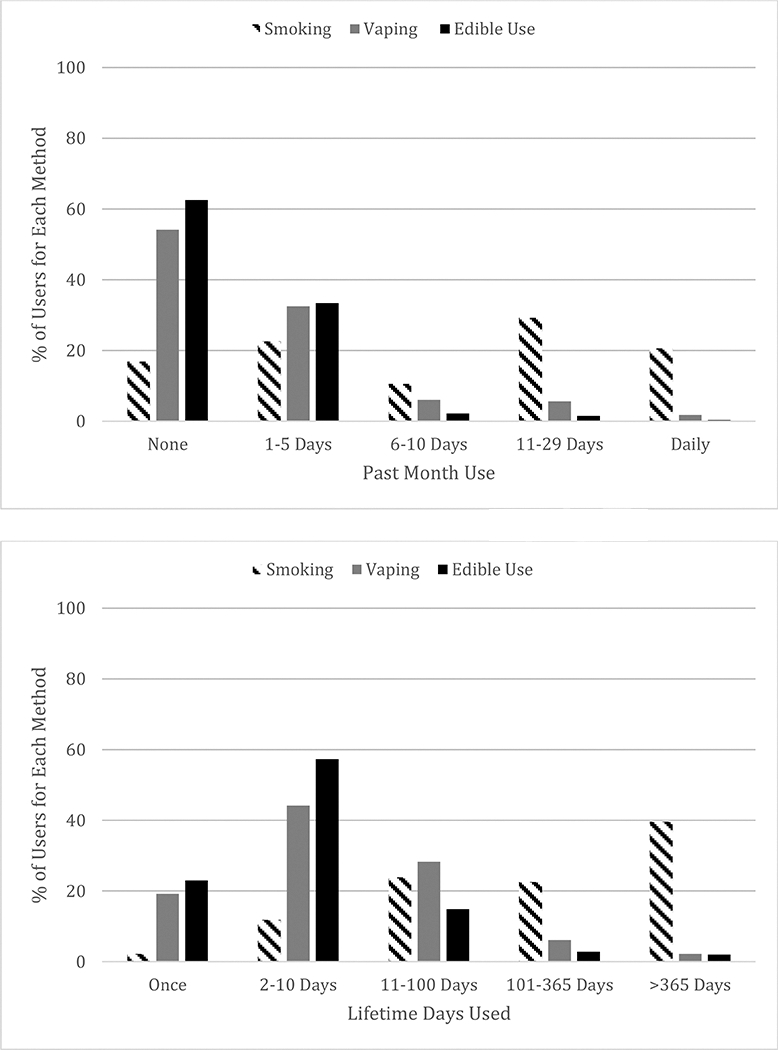

Lifetime and current frequencies of cannabis smoking, vaping, and edible use are displayed in Figure 1. The majority (62%) of cannabis smokers reported smoking more than 100-days in their lifetime, whereas the majority (63%) of those who had ever vaped cannabis reported 10 or fewer days of lifetime vaping, and the vast majority (80%) of those who had used edibles reported 10 or fewer days of edible use. Regarding past month use, 83% of lifetime smokers smoked cannabis during the past month, 46% of those who had vaped reported vaping cannabis in the last month, and 38% of those who had ever used edibles reported past month edible use. Thus, the sample consisted of mostly chronic users. These patterns suggest that adolescents who vaped cannabis or used edibles used these methods less regularly than those adolescents who smoked cannabis, which tended to be far more stable and frequent.

Figure 1.

Current (Past Month) and Lifetime Days Used among Adolescents who Smoke, Vape, or Use Cannabis Edibles Note: The graphs depict current and lifetime use patterns for those adolescents that endorsed ever cannabis smoking, vaping, and edible use. Smoking group represents all adolescents that have ever smoked cannabis, vaping group represents all adolescents that have ever vaped cannabis, and finally edible group represents all adolescents that have ever used cannabis edibles.

3.2.2. Transition and preference of cannabis administration methods.

The majority of adolescents (95%) reported smoking as the first method they used to administer cannabis, with only 3% reporting edible use and 1% reporting vaping as their first methods. For those who endorsed having used at least two of these methods to consume cannabis (n = 1780), 65% reported edibles as the second method they tried, and 29% reported vaping as their second method. Of those that endorsed all three methods (n = 958), 63% reported vaping as the third method they tried and 36% reported edibles as their third method. The majority (65%) of those who initiated edible use after smoking did so within a week to a year after first smoking cannabis. Similarly, the majority (64%) of those who initiated vaping did so within a week to a year after first smoking cannabis. Also, among those who reported using all three methods, most indicated preference for smoking (82%), followed by vaping (9%), and then edibles (8%). Last, the great majority of adolescents (94%) endorsed “no” when asked a yes/no question of “do you think marijuana is addictive.” These trends suggest that most adolescents initiated cannabis use via the route of smoking (and endorsed smoking as their preferred route), and then tried cannabis edibles or vaping cannabis. Additionally, the overwhelming majority of adolescents did not believe cannabis to be an addictive substance.

3.3. Age of Initiation and Other Substance Use

Next, we explored use patterns of cigarettes, electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS), and other substances (Table 1), and also the mean age of first use across the different cannabis administration methods and other substances (Table 2). The majority of adolescents endorsed lifetime use of nicotine, both in the form of ENDS (71%) and cigarettes (73%); half of lifetime ENDS-users reported ENDS use in the past 30-days, and 58% of lifetime cigarette users smoked cigarettes in the last 30-days. The majority of youth (91%) had ever used alcohol; subsequent to alcohol, pain killers (39%) and “study” drugs, such as Adderall or Ritalin (38%), were the other top substances ever used (Table 1). Younger ages of initiation for smoking cigarettes and smoking cannabis were reported, as were older ages of initiation for vaping cannabis. The first vape experience with nicotine and first vape experience with flavors occurred around the same age; the first use of cannabis edibles and first experience with vaping flavors also occurred around the same age (Table 2). Adolescents who reported use of more cannabis administration routes (ranging from 1–3) reported the greatest mean number of other drug use classes (ranging from 1–9); (3 routes: M= 3.8, 2 routes: M= 2.7, 1 route: M= 2.1) [F(2, 2627) = 182.34, p < .001]). Findings indicate that these cannabis-using adolescents reported high rates of nicotine use and also substantial use of other substances. Additionally, variability in youth’s methods of cannabis administration was associated with the number of other substances youth have tried.

Table 2:

Characteristics Regarding Age of First Use, Lifetime Vaping of Multiple Substances, First Substance Vaped, and Types of Substances Vaped

| M(SD) or % | n | |

|---|---|---|

| Age of First Usea | ||

| Smoking Cigarettes | 13.1 (2.5) | 1912 |

| Cannabis (Any Method) | 13.7 (1.8) | 2630 |

| Smoking Cannabis | 13.8 (1.9) | 2616 |

| Vaping Nicotine | 14.5 (1.5) | 1858 |

| Vaping Flavors | 14.7 (1.5) | 2147 |

| Cannabis Edibles | 14.9 (1.6) | 1596 |

| Vaping Cannabis | 15.3 (1.5) | 1156 |

| Lifetime Vaping of Multiple Substances Among Different Subgroups | ||

| Ever Vaped Combination of Flavor and Nicotine Among Those Who Had Vaped Flavorb | 55.5 | 2147 |

| Ever Vaped Combination of Flavor and Cannabis Among Those Who Had Vaped Flavor and Vaped Cannabisc | 20.1 | 1017 |

| Ever Vaped Combination of Nicotine and Cannabis Among Those Who Had Vaped Nicotined | 13.8 | 1858 |

| First Substance Vaped Among Those Who Had Ever Vaped Nicotinee | 883 | |

| Nicotine | 69.1 | |

| Cannabis | 26.7 | |

| Cannabis and Nicotine Mix | 4.2 | |

| First Substance Vaped Among Those Who Had Vaped Cannabis and Vaped Flavor c | 1017 | |

| Cannabis and Flavor Mix | 1.2 | |

| Nicotine | 7.2 | |

| Cannabis | 19.2 | |

| Nicotine and Flavor Mix | 25.7 | |

| Flavor | 40.1 | |

| Unknown | 6.7 | |

| Types of Cannabis Ever Vaped Among Those Who Had Vaped Cannabisf | 1156 | |

| Cannabis Plant Material | 74.1 | |

| Cannabis Concentrates | 68.2 | |

| E-liquids Containing Cannabis | 29.1 |

Note: N = 2630.

Among those adolescents who reported ever using each respective substance and method.

Among those adolescents who reported ever vaping flavor.

Among those adolescents who have ever vaped cannabis and vaped flavor.

Among those adolescents who reported ever vaping nicotine

Among those adolescents who have ever vaped cannabis and vaped nicotine.

Among those adolescents who have ever vaped cannabis.

3.4. Vaping Trends

3.4.1. Vaporizer typology and reasons for vaping cannabis.

Among those who reported ever vaping cannabis, the most commonly used vaping device was a pen vaporizer (58%) followed by portable (25%) and tabletop (6%) vaporizers. Cannabis plant material and concentrates were the forms of cannabis most commonly used for vaping, followed by e-liquids (see Table 2). Only about 25% (n = 291) of adolescents that had ever vaped owned their own vaping device. Among vaping device owners, 71% (n = 206) bought their vaporizer and reported obtaining their device from the following places: smoke/head shop (32%), friend/family members (30%), the internet (27%), dispensary (3%), gas station/convenience store (2%), or other (7%).

Reasons for vaping compared to smoking cannabis were evaluated among those who preferred vaping (n = 116) and those who preferred smoking (n = 1498)2. Among the group who preferred vaping, the majority of youth indicated that they favored vaping to smoking because it was more discreet (67%), healthier (66%), better tasting (53%), less harsh (64%), lower cost (60%), and had better effects (64%). Even among participants who indicated an overall preference for smoking versus vaping, the discretion of vaping was perceived as a benefit (56%).

3.4.2. First substance vaped and vaping mixed substances.

Next, we examined the chronology and patterns of vaping cannabis and other substances. With regards to vaping mixed substances, over half (56%) of adolescents who had ever vaped flavors reported mixing flavors with nicotine in their vaporizer device. Of that same group, most (40%) vaped flavors-only (no psychoactive substance mixed in) or flavors mixed with nicotine (26%) the first time they vaped, followed by cannabis alone (19%), nicotine only (7%), and flavor mixed with cannabis (1%). These patterns suggest that adolescents who have vaped flavors commonly vaped a mix of flavors with nicotine, and that this nicotine-flavor mixture is one of the more common substances these teens vaped initially, along with flavors-only and cannabis-only.

Of those adolescents who had lifetime experience with ENDS, only a small subgroup (14%) reported eve mixing nicotine and cannabis in their vaporizer device. Among those who had vaped both cannabis and flavors, 20% had mixed flavors with cannabis. Last, among the subgroup of adolescents who reported ever vaping cannabis and vaping nicotine, the majority of youth reported nicotine (69%) as their first vaped substance, followed by cannabis (27%) and mix of cannabis and nicotine (4%). These trends suggest that nicotine was the first substance vaped among most youth that have ever vaped cannabis and nicotine, and that vaping a mix of cannabis and other substances, such as flavors and nicotine, was rare among adolescents with various vaping experiences.

4. Discussion

Despite the growing availability of new cannabis administration methods, the majority of adolescents in this social-media recruited sample with a lifetime history of vaporization/edible use still preferred to smoke cannabis. Youth cannabis administration preferences manifested behaviorally in a pattern of smoking cannabis more frequently and consistently than vaping or using edibles, although a substantial number of youth had tried and continued to use those alternative routes. These findings are comparable to previous work with adult cannabis users that used similar social-media recruitment and survey questions 8, and also with results from state-level surveys with adolescent cannabis users12. Among the adolescents who had tried multiple administration methods, the great majority of adolescents in the current sample initiated cannabis use via smoking, and advanced to using edibles or vaping cannabis within a year of first smoking. Similar to work on heterogeneity in cannabis administration methods and heavy drug use22, those adolescents who had tried the most cannabis administration routes (all three modes vs. one and two modes) reported use of the greatest number of other drug classes. This could have important implications for identification of higher risk youth for intervention efforts.

The majority of this sample continued to prefer smoking cannabis even after experiencing the alternatives. Such findings were somewhat surprising as we expected that more youth might initiate cannabis use via vaping or edibles because of the increased availability of these methods and, specific to this sample, the perception of increased discretion (with reference to vaping). This preference for discretion is observed among adult cannabis users 7 and similar to that expressed by ENDS-using youth who prefer ENDS to cigarettes because they can be easily concealed from adults 23. Moreover, we anticipated that once youth tried vaping or edibles, they would be more likely to choose to use these routes more frequently and perhaps reduce smoking cannabis, yet to date such preferences for vaping have not yet resulted in major shifts away from smoking. The observed patterns could be indicative of continued easier access to the materials required to smoke cannabis compared to the other routes, or the preference of the effects of smoked cannabis, or multiple other factors. It will be important to continue to monitor these patterns of initiation and ongoing use as cannabis legalization progresses and new products and methods become more familiar and available in the U.S. and elsewhere.

As for vaping trends, adolescents obtained vaping devices most commonly from smoke/head shops, friends and family members, or the internet, and consistent with other studies on adolescent vaping behaviors,24 adolescents reported using cannabis plant material and concentrates in their vaping devices at similar rates. Use of highly potent cannabis concentrates may increase the probability of problematic cannabis use because these products can provide a more immediate and potent ‘high’ (greater reinforcing effects) than smoking cannabis, and possibly more substantial withdrawal and tolerance 25. Those crafting legislation or regulations related to legal cannabis might consider tight restrictions on both THC content in cannabis products in general, and on sales of vaping devices to avoid selling to minors (e.g., use of age verification systems26).

This sample of cannabis-using youth also reported high rates of nicotine use, both in the form of combustible cigarettes (73% lifetime, 58% past month) and ENDS (71% lifetime, 50% past month). These rates mirror the high rates of cannabis use reported by youth ENDS and cigarette users 27,28. Age of initiation reports for tobacco and cannabis in this study suggest earlier ages of initiation for smoking cigarettes and smoking cannabis, slightly older initiation ages for vaping nicotine, vaping flavors, and use of cannabis edibles, and later ages of initiation for vaping cannabis. Consistent with that progression, nicotine and flavors were frequently reported as the first substances vaped among groups with various substance use experiences. More fine-grained and prospective research is needed to more directly investigate the potential role that cigarette and ENDS use may play in the initiation of cannabis use through prospective assessment with children transitioning into adolescence and later into emerging adulthood. Additional work is also needed to disentangle the complex and likely bidirectional relationship of cannabis and nicotine co-use among youth, especially taking into consideration the varying routes of nicotine and cannabis administration (spliffs, blunts, combined in a pipe or vaporizer) and simultaneous administration of nicotine and cannabis29–31.

It is important to recognize the limitations of the current investigation. First, this study included self-identified adolescent cannabis users in the U.S. recruited through advertisements displayed on Facebook and Instagram. The results may not generalize to youth cannabis users who do not use Facebook and Instagram, or those who are not associated with cannabis interests on these platforms. Other social media platforms, such as Snapchat, could elicit different samples and may be more relevant to and representative of the adolescent population32. These types of platforms should be incorporated in future studies. Ethnic minorities were underrepresented in this sample, and youth from other countries were excluded from the sampling strategy. Targeting such groups in future studies would help inform if the patterns observed in the current study are similar across different ethnicities and nationalities. Second, the cross-sectional nature of the study does not allow for causal conclusions related to temporal patterns of substance initiation, and the report of age of initiation was limited by use of only yearly intervals and thus does not afford the precision of more specific indices of age. Last, this study assessed smoking, vaping, and edible use, but not other methods of use, such as transdermal products and other routes25,33.

Epidemiological evaluation of emerging trends of cannabis use among youth requires a multi-pronged approach using several types of sampling strategies to both detect new indicators of problematic behavior early as well as monitor how those behaviors evolve across time among differing populations. The current investigation and prior studies8,18,19,34 provide examples of how social media can be leveraged to efficiently, cost-effectively, and rapidly recruit and survey large samples of youth (or adults) across the U.S. who are using cannabis regularly. The current findings suggest that cannabis smoking remains the most common route of initiation and administration among adolescents, although substantial numbers of youth have tried and continue to vape and use edibles. Combining the knowledge gained via targeted samples generated from novel sampling platforms, such as those used in the current study, with probabilistic samples generated by surveys like Monitoring the Future and National Survey on Drug Use and Health, we will begin to be able to create more comprehensive pictures of the complicated set of interrelated forces affecting youth risk-taking behaviors.

Supplementary Material

Implication and Contribution.

This study contributes to the literature by leveraging social-media to survey a large sample of adolescent cannabis users. The most frequent and consistent route of cannabis use was smoking, although many reported vaping and edible use. Smoking remains the typical method of initiating cannabis, and also the preferred administration method.

Acknowledgments

Research supported by the National Institute of Drug Abuse [T32DA037202; P30DA029926; R01DA032243; R01DA01518]

Abbreviations

- (U.S.)

United States

- (ENDS)

Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems

Footnotes

This age range was selected to primarily represent middle and high school students using cannabis; the lower age cutoff was determined by the Institutional Review Board and the higher age cutoff was chosen to capture most adolescents in high school, with the understanding that some first-year college students and high school graduates may participate.

Chi Square analyses comparing the groups who preferred vaping cannabis to those who preferred smoking cannabis on the reasons they favored vaping to smoking were all statistically significant across the six categories (i.e., healthier, better tasting, less harsh, lower cost, better effects, p < .001; more discreet, p = .022.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Appendix A contains the contents of the Administration of Cannabis and Other Substances Survey. The Appendix also provides information on the branching logic used throughout the survey.

References

- 1.ElSohly MA, Mehmedic Z, Foster S, Gon C, Chandra S, Church JC. Changes in Cannabis Potency Over the Last 2 Decades (1995–2014): Analysis of Current Data in the United States. Biol Psychiatry 2016; 79 (7):613–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Meich RA, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2016: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okaneku J, Vearrier D, McKeever RG, LaSala GS, Greenberg MI. Change in perceived risk associated with marijuana use in the United States from 2002 to 2012. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2015; 53 (3):151–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pacek LR, Mauro PM, Martins SS. Perceived risk of regular cannabis use in the United States from 2002 to 2012: differences by sex, age, and race/ethnicity. Drug Alcohol Depend 2015; 149:232–244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Unit RMHSI. The Legalization of Marijuana in Colorado: The Impact October 2017. 2017.

- 6.Etter JF. Electronic cigarettes and cannabis: an exploratory study. Eur Addict Res 2015; 21 (3):124–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malouff JM, Rooke SE, Copeland J. Experiences of marijuana-vaporizer users. Subst Abus 2014; 35 (2):127–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee DC, Crosier BS, Borodovsky JT, Sargent JD, Budney AJ. Online survey characterizing vaporizer use among cannabis users. Drug Alcohol Depend 2016; 159:227–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh T, Arrazola RA, Corey CG, Husten CG, Neff LJ, Homa DM, et al. Tobacco Use Among Middle and High School Students--United States, 2011–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016; 65 (14):361–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnston LDM RA, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Patrick ME, Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use: 1975–2017: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnston L, O’Malley P, Miech R, Bachman J, Schulenberg E. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2015: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Environment CDoPH Marijuana Use Among Youth in Colorado. Healthy Kids Colorado Survey2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Education CDo. California Healthy Kids Survey; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friese B, Slater MD, Battle RS. Use of Marijuana Edibles by Adolescents in California. J Prim Prev 2017; 38 (3):279–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friese B, Slater MD, Annechino R, Battle RS. Teen Use of Marijuana Edibles: A Focus Group Study of an Emerging Issue. J Prim Prev 2016; 37 (3):303–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cavazos-Rehg PA, Zewdie K, Krauss MJ, Sowles SJ. “No High Like a Brownie High”: A Content Analysis of Edible Marijuana Tweets. Am J Health Promot 2018; 32 (4):880–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borodovsky JT, Lee DC, Crosier BS, Gabrielli JL, Sargent JD, Budney AJ. U.S. cannabis legalization and use of vaping and edible products among youth. Drug Alcohol Depend 2017; 177:299–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramo DE, Rodriguez TM, Chavez K, Sommer MJ, Prochaska JJ. Facebook Recruitment of Young Adult Smokers for a Cessation Trial: Methods, Metrics, and Lessons Learned. Internet Interv 2014; 1 (2): 58–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thornton LK, Harris K, Baker AL, Johnson M, Kay-Lambkin FJ. Recruiting for addiction research via Facebook. Drug Alcohol Rev 2016; 35 (4):494–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borodovsky JT, Marsch LA, Budney AJ. Studying cannabis use behaviors with Facebook and web surveys: methods and insights. Journal of Medical Internet Research In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Division USCBP. Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015 2016.

- 22.Baggio S, Deline S, Studer J, Mohler-Kuo M, Daeppen JB, Gmel G. Routes of administration of cannabis used for nonmedical purposes and associations with patterns of drug use. J Adolesc Health 2014; 54 (2):235–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kong G, Morean ME, Cavallo DA, Camenga DR, Krishnan-Sarin S. Reasons for Electronic Cigarette Experimentation and Discontinuation Among Adolescents and Young Adults. Nicotine Tob Res 2015; 17 (7):847–854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morean ME, Kong G, Camenga DR, Cavallo DA, Krishnan-Sarin S. High School Students’ Use of Electronic Cigarettes to Vaporize Cannabis. Pediatrics 2015; 136 (4):611–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loflin M, Earleywine M. A new method of cannabis ingestion: the dangers of dabs? Addict Behav 2014; 39 (10):1430–1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roodbeen RT, Schelleman-Offermans K, Lemmens PH. Alcohol and Tobacco Sales to Underage Buyers in Dutch Supermarkets: Can the Use of Age Verification Systems Increase Seller’s Compliance? J Adolesc Health 2016; 58 (6):672–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Demissie Z, Everett Jones S, Clayton HB, King BA. Adolescent Risk Behaviors and Use of Electronic Vapor Products and Cigarettes. Pediatrics 2017; 139 (2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Conway KP, Green VR, Kasza KA, Silveira ML, Borek N, Kimmel HL, et al. Co-occurrence of tobacco product use, substance use, and mental health problems among youth: Findings from wave 1 (2013–2014) of the population assessment of tobacco and health (PATH) study. Addict Behav 2018; 76:208–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eggers ME, Lee YO, Jackson K, Wiley JL, Porter L, Nonnemaker JM. Youth use of electronic vapor products and blunts for administering cannabis. Addict Behav 2017; 70:79–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schauer GL, Rosenberry ZR, Peters EN. Marijuana and tobacco co-administration in blunts, spliffs, and mulled cigarettes: A systematic literature review. Addict Behav 2017; 64:200–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schauer GL, Peters EN. Correlates and trends in youth co-use of marijuana and tobacco in the United States, 2005–2014. Drug Alcohol Depend 2018; 185:238–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor J What To Expect When You Start Advertising On Snapchat. Forbes CommunityVoice: Forbes; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raber JC, Elzinga S, Kaplan C. Understanding dabs: contamination concerns of cannabis concentrates and cannabinoid transfer during the act of dabbing. J Toxicol Sci 2015; 40 (6):797–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Borodovsky JT, Crosier BS, Lee DC, Sargent JD, Budney AJ. Smoking, vaping, eating: Is legalization impacting the way people use cannabis? Int J Drug Policy 2016; 36:141–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.