Abstract

BNIP3 is an atypical BH3-only member of the Bcl-2 family with pro-death, pro-autophagic, and cytoprotective functions, depending on the type of stress and cellular context. Recently, we demonstrated that BNIP3 stimulates the migration of epidermal keratinocytes under hypoxia. In the present study found that autophagy and BNIP3 expression were concomitantly elevated in the migrating epidermis during wound healing in a hypoxia-dependent manner. Inhibition of autophagy through lysosome-specific chemicals (CQ and BafA1) or Atg5-targeted small-interfering RNAs greatly attenuated the hypoxia-induced cell migration, and knockdown of BNIP3 in keratinocytes significantly suppressed hypoxia-induced autophagy activation and cell migration, suggesting a positive role of BNIP3-induced autophagy in keratinocyte migration. Furthermore, these results indicated that the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by hypoxia triggered the activation of p38 and JNK mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) in human immortalized keratinocyte HaCaT cells. In turn, activated p38 and JNK MAPK mediated the activation of BNIP3-induced autophagy and the enhancement of keratinocyte migration. These data revealed a previously unknown mechanism that BNIP3-induced autophagy occurs through hypoxia-induced ROS-mediated p38 and JNK MAPK activation and supports the migration of epidermal keratinocytes during wound healing.

Subject terms: Collective cell migration, Macroautophagy

Introduction

Wound healing is a complex multistep process involving three partially overlapping phases as follows: inflammation, re-epithelialization, and tissue remodeling. During re-epithelialization, epidermal keratinocytes migrate into the wound site, proliferate, and differentiate to reconstruct the epidermal barrier1. Defects in keratinocyte migration usually result in unsatisfied wound repair2,3. It has been implicated that wound-induced hypoxia promotes keratinocyte motility and enhances keratinocyte migration4,5, while the underlying mechanisms remain largely unclear.

BNIP3 (Bcl-2 and adenovirus E1B 19-kDa interacting protein 3) is a single transmembrane protein that is mainly located in the outer membrane of mitochondria. Previously, we determined that BNIP3 is upregulated by hypoxic exposure and plays a critical role in hypoxia-induced keratinocyte motility and migration6. Others have elucidated that BNIP3 significantly triggers cell autophagy in hypoxic cardiomyocytes7 and that autophagy clearly promotes cell migration in some cases8. Thus, we speculated that autophagy induced by BNIP3 might serve a pro-migratory function.

Macroautophagy (hereafter referred to as autophagy) was initially described based on its ultrastructural features of double-membraned structures that surround the cytoplasm and organelles in cells, which are known as autophagosomes9. Many studies have reported that autophagy is involved in cell migration. However, whether autophagy leads to the enhancement or impairment of cell migration is controversial. The induction of autophagy has a pro-migratory effect in some conditions, whereas it is associated with the inhibition of cell migration in other conditions10,11. Recently, the induction of autophagy by BNIP3 has been demonstrated to be essential for the differentiation of keratinocytes and the protection of keratinocytes from UVB-induced apoptosis12,13, whereas the role of BNIP3-induced autophagy in keratinocytes during wound healing remains unclear.

Although BNIP3 is known to be highly upregulated under hypoxia through the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1), the HIF-1-independent mechanisms and posttranscriptional mechanisms are also crucial for BNIP3 expression in different cells and tissues14–17. Hypoxia is well established to stimulate several signaling pathways, including the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), HIF-1, and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways. MAPK is an evolutionary conserved serine/threonine protein kinase playing an important role in fundamental cellular processes, such as proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, survival, and migration18. The extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and p38 kinase pathways are the three components of the MAPK pathway in mammals. The ERK pathway is primarily activated by growth factors, such as epidermal growth factor, whereas the JNK and p38 signaling pathways are activated by various stress stimuli, including hypoxia, UVB radiation, and inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α19,20. Additionally, hypoxia has been shown to cause the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which are also involved in activating MAPK signaling pathways21.

The present study investigated the molecular mechanisms by which BNIP3 acts as a pro-migratory factor in response to hypoxia during wound healing. The present data demonstrated that ROS accumulation mediated by hypoxia exposure triggered the activation of p38 and JNK MAPK in human immortalized keratinocyte HaCaT cells, in turn upregulating BNIP3-induced autophagy. Moreover, the present results also indicated that autophagy inhibition significantly impairs hypoxia-induced keratinocyte migration. These data revealed a previously unknown mechanism that BNIP3-induced autophagy occurs through hypoxia-induced ROS-mediated p38 and JNK MAPK activation and supports the migration of epidermal keratinocytes during wound healing.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health (NIH Pub. No. 85–23, revised 1996) and approved by the Animal Experiment Ethics Committee of the Third Military Medical University in Chongqing, China.

In vivo wound closure assay

For wounding experiments, 8- to 12-week-old male/female C57BL/6 mice were anesthetized through intraperitoneal administration of sodium pentobarbital, and full-thickness wounds were made on the mid-dorsal skin with 5-mm disposable biopsy punches. For immunofluorescence staining, skins were harvested 5, 10 or 15 days post wounding and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. The frozen sections were used to detect the expression of BNIP3, LC3, and Atg5.

Cells and mouse skin organ culture

Human immortalized keratinocyte HaCaT cells were obtained from the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing, China. Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (SH30809, HyClone) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (10100139, Gibco), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Beyotime, China). Cells were incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2, and 95% humidity. Skin organ culture was performed as previously described22,23. Skin specimens were prepared from the dorsal skin of newborn C57BL/6 mice (postnatal day 1–3) and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified MEM (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS: Gibco, NY, USA), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Beyotime, China).

Hypoxia exposure

Hypoxic conditions of 2% O2, 5% CO2 and 93% N2 were created by a constant flow of nitrogen using a Forma Series II Water Jacket CO2 incubator (model: 3131; Thermo Scientific), which maintained a precise culturing environment (37 °C) and desired O2 level. A p38 inhibitor (SB203580, Invitrogen, 5 μM), JNK inhibitor (SP600125, Beyotime, 5 μM), and an antioxidant (NAC, Sigma-Aldrich, 5 mM) were respectively added to the cultures and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min before hypoxic treatment. Other reagents used in the present study included actinomycin D (ACTD; AA007, Genview), bafilomycin A1 (BafA1; B1793, Sigma), and chloroquine (CQ; C6628, Sigma).

Western blot analysis

Whole cell extracts and mouse skin specimens were prepared using RIPA lysis buffer (P0013, Beyotime) and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. Supernatants were collected, and protein concentrations were detected using the Bradford Protein Quantification Kit (500-0205, Bio-Rad Laboratories). Protein samples were loaded and separated by SDS-PAGE, then transferred to PVDF membrane (Millipore). Membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with specific primary antibodies. Membranes were then incubated with secondary antibodies and visualized using ChemiDoc XRS System (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The following primary antibodies were used for Western blot: BNIP3 (ab109362, Abcam), LC3B (L7543, Sigma), P62 (88588, Cell Signaling Technology), Atg5 (12994, Cell Signaling Technology), p38 (8690, Cell Signaling Technology), p-p38 (4511, Cell Signaling Technology), JNK (sc-7345, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), p-JNK (sc-293136, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Atg7 (8558, Cell Signaling Technology), Atg16L1 (8089, Cell Signaling Technology), Beclin-1 (3495, Cell Signaling Technology), p-ULK1 (5869, Cell Signaling Technology), ULK1 (8054, Cell Signaling Technology) and GAPDH (HRP-60004, Proteintech).

Immunoprecipitation (IP)

To investigate the protein interaction between BNIP3 and LC3, whole-cell extracts or wound specimens were prepared in lysis buffer for Western blot and IP (Beyotime, P0013) and centrifuged at 14,000 g for 15 min. The supernatants were incubated with 2 μg of anti-BNIP3 (ab10433, Abcam), anti-LC3B (L7543, Sigma) for 8 h at 4 °C, and then precipitated with Protein A/G Plus-Agarose (Santa Cruz) overnight at 4 °C. Total and binding proteins were detected by Western blotting.

ROS detection

ROS levels were measured with a fluorescence microscope using the redox-sensitive fluorescent dye, dihydroethidium (DHE; D7008, Sigma-Aldrich). Frozen skin sections and HaCaT cells were incubated with DHE (5 μM) at 37 °C for 20 min, washed twice with PBS to remove extra dye, and then observed and imaged under a fluorescence microscope. The fluorescence intensity of HaCaT cells was detected using a microplate reader with an excitation wavelength of 510 nm and an emission wavelength of 600 nm for DHE.

Transmission electron microscopy

HaCaT keratinocytes were harvested and immediately fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde overnight at 4 °C and postfixed with 2% osmium tetroxide for 1 h at 37 °C. After generating sections, samples were stained with lead citrate and uranyl acetate, and they were then observed under a transmission electron microscope (JEM-1400PLUS, Japan)24.

Lentivirus infection and siRNA transfection

For stable cell line construction, lentivirus vectors containing shRNA against human BNIP3 or scrambled shRNA were constructed. Lentiviruses were generated by the GeneChem Company (Shanghai, China) and used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Knockdown of BNIP3 was confirmed by immunoblotting. For RNA interference, cells were transfected with small interfering siRNAs specific for human Atg5 and HIF-1α, or the corresponding scramble siRNA using Lipofectamine 2000 (11668027, Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. siRNAs were purchased from GenePharma Company (Shanghai, China).

Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation was determined using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8, Beyotime, China) as previously described25. HaCaT cells were seeded at 2 × 103/well in 96-well plates in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS. Plates were pre-incubated for 24 h in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37 °C before CCK-8 solution (10 μL) was added to each well of the plate. Plates were then incubated for 1 h, and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Thermo, USA).

Immunofluorescence staining

After treatment, samples (cells cultured on glass coverslips and frozen mouse skin sections) were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min after being rinsed twice with PBS. Samples were then incubated with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight, washed three times with PBS, and then stained with fluorescent secondary antibodies at 37 °C for 1 h. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (HyClone, USA) before imaging. Images were acquired using a Leica Confocal Microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). The following primary antibodies were used: BNIP3 (Abcam, ab109362), BNIP3 (Abcam, ab10433), LC3B (L7543, Sigma), and Atg5 (12994, Cell Signaling Technology). The following secondary antibodies were used: Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen, A32731 rabbit) and Alexa Fluor 555 (Invitrogen, A32732 rabbit).

Wound-healing assay

Monolayers of cells plated in 12-well plates were wounded by a 10-μL plastic pipette tip after being incubated at 37 °C for 2 h with mitomycin-C (S8146, Selleck, final concentration: 5 μg/mL) to inhibit cell proliferation, and the wells were then rinsed with medium to remove any cell debris. The wound-healing process was monitored with an inverted light microscope (Olympus, Japan). The cell migratory capacity was defined as the wound-closure rate (%), which was analyzed using NIH ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/).

Single-cell motility assay and quantitative analysis

HaCaT keratinocytes were seeded into 24-well plates at a density of 0.5 × 104/cm2 in RPMI 1640 medium. Time-lapse imaging was then performed with a Zeiss imaging system (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Jena, Germany), which was equipped with a CO2- and temperature-controlled chamber. Images were acquired every 3 min for 3 h. Cellular trajectories were obtained by tracing the position of the cell nucleus at frame intervals of 6 min using NIH ImageJ software, and the trajectory speed (μm/min) of each cell was defined as the total length (μm) of the trajectories divided by time (min), which reflected cell motility.

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as mean ± SEM unless otherwise stated. Comparisons between two groups were performed using a two-tailed unpaired t-test. Statistical significance among three or more groups was estimated by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

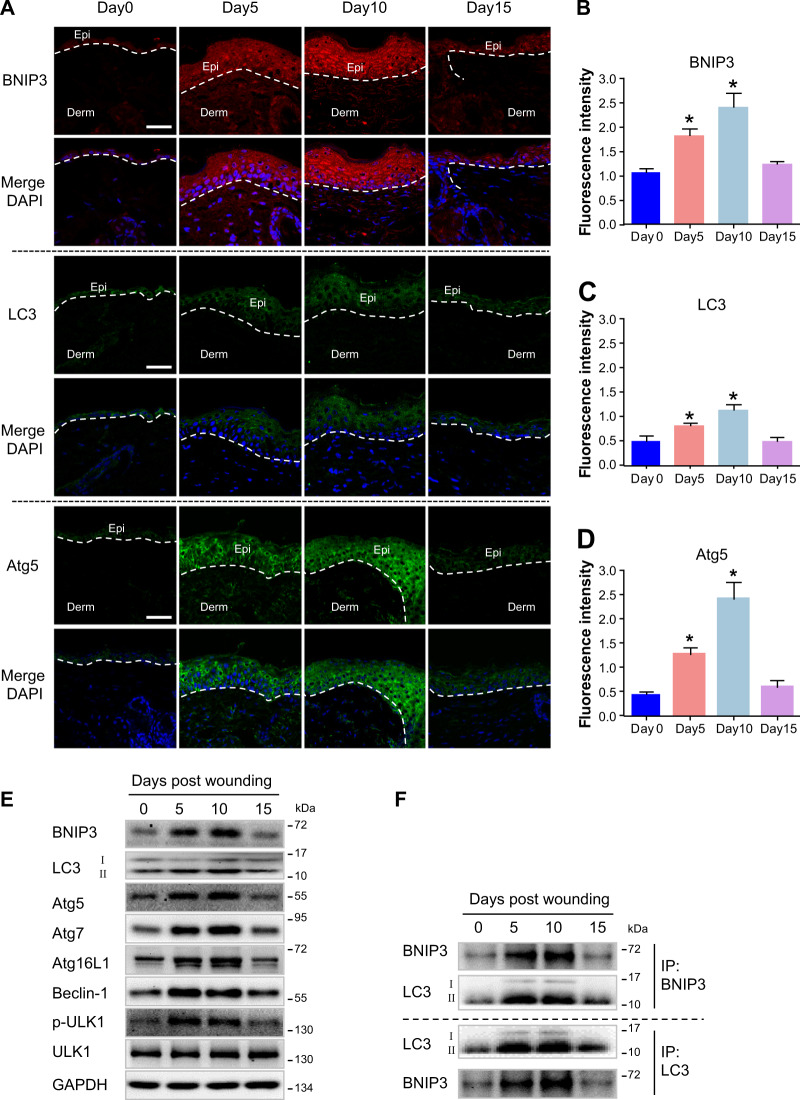

Autophagy is involved in epidermal migration during wound healing

As previously demonstrated BNIP3 is upregulated and has pro-migratory effects on mouse epidermal keratinocytes upon hypoxic conditions in vitro6. Additionally, BNIP3, as a potent inducer of autophagy, is expressed in human skin epidermis and is also sufficient to promote keratinocyte differentiation through induction of autophagy12. To reveal the potential role of BNIP3 in keratinocyte migration during epidermal wound healing in vivo, expression patterns of key autophagy markers, including BNIP3, LC3, and autophagy-related protein 5 (Atg5), in the mouse skin were visualized using confocal microscopy (Fig. 1a–d). Following wounding, BNIP3, LC3, and Atg5 were markedly upregulated in migrating epidermis (day 5). Epidermal BNIP3, LC3, and Atg5 were still upregulated when the wound was close to re-epithelialization (day 10), and they decreased to levels comparable to that observed in normal skin epidermis when re-epithelialization was fully completed (day 15).

Fig. 1. Upregulation of BNIP3 and activation of autophagy in epidermis during wound healing.

a Immunofluorescence staining of BNIP3, LC3, and Atg5 in normal unwounded skin (day 0) and in day 5, day 10, and day 15 wounded sections obtained from C57BL/6 mice showing upregulation of BNIP3 and activation of autophagy in migrating epidermis during normal wound re-epithelialization. Wounds were close to re-epithelialization on day 10 and fully re-epithelialized on day 15. Nuclei were stained with 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, blue). Scale bar = 50 μm. Epi epidermis, Derm dermis. Narrow dotted line indicates the interface between epidermis and dermis or leading edge of migrating epidermis (day 5 and day 10). b–d Graphs indicate the relative fluorescence intensities as determined by ImageJ software. The results are represented by the mean ± SEM (n = 3). e The indicated wound specimens were lysed in lysis buffer and utilized for the detection of LC3, Atg5, Atg7, Atg16L1, Beclin-1, p-ULK1, and BNIP3. f The indicated wound specimens were lysed in lysis buffer and immunoprecipitated with anti-BNIP3 or anti-LC3 antibodies followed by immunoblotting with anti-LC3 or anti-BNIP3 antibody. *P < 0.05 vs. day 0 group

Western blot analysis demonstrated significant increases of autophagy-related proteins, including LC3, Atg5, Atg7, Atg16L1, Beclin-1, p-ULK1, and BNIP3, in the epidermis during wound healing (Fig. 1e and Fig. S5A). The upregulation of autophagy in migrating epidermis suggested that a higher level of autophagy is required for normal wound re-epithelialization. Furthermore, the interaction between LC3 and BNIP3 was assessed using a co-immunoprecipitation assay. An interaction between BNIP3 and LC3 was found in the epidermis, and it was remarkably elevated during wound healing (Fig. 1f and Fig. S5B). Together, these observations indicated a role of BNIP3-regulated autophagy during re-epithelialization.

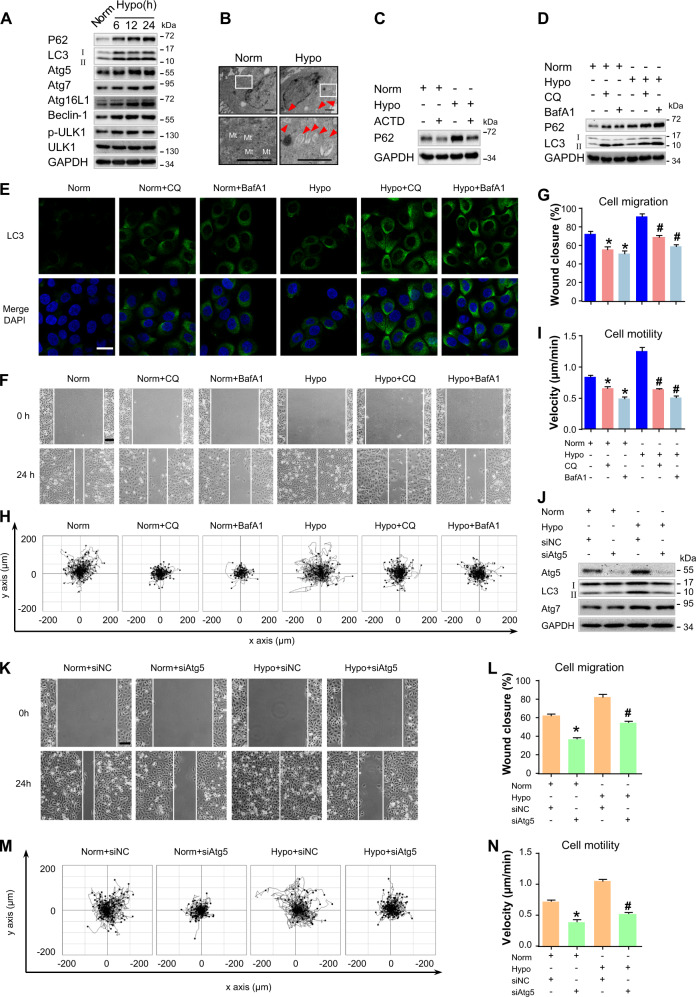

Autophagy is activated in hypoxic keratinocytes and is required for cell migration

A previous study has reported the hypoxic microenvironment in the wound edge at the early stage after wounding25. Then, the effect of hypoxia on autophagy in skin was investigated. HaCaT keratinocytes were exposed to normoxic conditions of 20% O2 or hypoxic conditions of 2% O2, and the expressions of LC3, p62, Atg5, Atg7, Atg16L1, Beclin-1, and p-ULK1 were then analyzed via western blotting. Hypoxia-elevated expressions of these autophagy-related proteins in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 2a and Fig. S6A). To further investigate the effects of hypoxia on autophagy, transmission electron microscopy was utilized. A greater number of double-membrane vesicles accumulated in hypoxic HaCaT keratinocytes compared to the control group (Fig. 2b). These results suggested an increased level of autophagy in hypoxic keratinocytes.

Fig. 2. Autophagy is activated in hypoxic keratinocytes and is required for cell migration.

a HaCaT cells were exposed to hypoxia (2%) and incubated for the indicated times, and total proteins were harvested for detection of autophagy markers (LC3, P62, Atg5, Atg7, Atg16L1, Beclin-1, and p-ULK1) via Western blotting. GAPDH was used as the loading control. b HaCaT cells were exposed to hypoxia (2%) for 6 h and were observed for autophagosomes using transmission electron microscopy. Representative micrographs are shown. The boxed areas represent higher magnification to illustrate details. Red arrows indicate autophagy vacuoles. Scale bar = 1 μm. Mt mitochondria. c HaCaT cells were treated with actinomycin D (ACTD, 5 nM) for 1 h to inhibit transcription and then incubated for 6 h under normoxic or hypoxic conditions. GAPDH was used as the loading control. d–i HaCaT cells were exposed to hypoxia (2%) and incubated for 6 h. Autophagy inhibitors, namely, chloroquine (CQ, 10 μM) and Bafilomycin A1 (BafA1, 10 nM), were added 1 h prior to hypoxia exposure. The extracted proteins were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies (d). e Fluorescence staining of LC3 expression (green) in the indicated HaCaT cells. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Wound-healing assays (f, g) and single-cell motility assays (h, i) were performed to test the effects of autophagy inhibitors on keratinocyte migration. Representative images of wound healing, including keratinocyte trajectories. Scale bar = 100 μm. Quantitative results are represented by the mean ± SEM (n = 3). *P < 0.05 vs. the Norm group, and #P < 0.05 vs. the Hypo group. j Western blotting was used to analyze Atg5, Atg7, and LC3 expression in HaCaT cells treated with 100 nM Atg5 siRNA (siAtg5) or siRNA-negative control (siNC) under indicated conditions. GAPDH was used as the loading control. The effects of Atg5 siRNA on keratinocyte migration were also determined by wound-healing assays (k, l) and single-cell motility (m, n) assays. Representative images of wound healing, including keratinocyte trajectories. Scale bar = 100 μm. Quantitative results are represented by the mean ± SEM (n = 3). *P < 0.05 vs. the Norm group, and #P < 0.05 vs. the Hypo group. Norm normoxia, Hypo hypoxia

P62 generally localizes to membranes of autophagosomes and is cleared by autophagy. The accumulation of p62 results from impaired autophagy in a series of cancers26. However, recent studies have shown that p62 level may be transcriptionally regulated26,27. To determine if hypoxia induction of p62 requires active transcription, HaCaT keratinocytes were pretreated with actinomycin D (ACTD, an inhibitor of mRNA synthesis28) for 1 h followed by hypoxic treatment for 6 h. ACTD completely blocked the increase of hypoxia-induced p62 expression (Fig. 2c and Fig. S6B), suggesting that initial increase in p62 levels requires the activation of transcriptional machinery under hypoxia.

To further determine if hypoxia induces autophagic flux, HaCaT keratinocytes exposed to normoxic or hypoxic conditions were treated with a lysosomal inhibitor (chloroquine, CQ; 10 μM) or bafilomycin A1 (BafA1, 10 nM). CQ primarily functions by causing an increase in lysosomal pH, which inhibits the activity of degradative enzymes and consequently leads to accumulation of vesicular organelles in the cytoplasm, thus blocking autophagy11,29. BafA1, a chemical inhibitor of vacuolar H + ATPase, blocks lysosomal acidification, and consequently inhibits autophagy9. The LC3-II levels in CQ- and BafA1-treated cells were significantly higher in hypoxic conditions compared to normoxic conditions (Fig. 2d and Fig. S6C). Moreover, treatment with CQ and BafA1 resulted in a significant increase of LC3 puncta in hypoxic keratinocytes (Fig. 2e), thereby reflecting an increase in autophagic flux in hypoxia.

Based on the results above, the role of autophagy in the regulation of keratinocyte migration was investigated. A significant wound gap remained in keratinocytes treated with CQ (10 μM) or BafA1 (10 nM), whereas the wound was almost completely healed in the control group (Fig. 2f, g). Similarly, CQ or BafA1 treatment markedly decreased the velocity of cell movement (Fig. 2h, i, Movie 1). Moreover, CQ (10 μM) and BafA1 (10 nM) significantly inhibited cell proliferation (Fig. S1A). To rule out the nonspecific effects of chemicals and further confirm the present results, cells were transfected with siRNA targeting Atg5 to specifically suppress autophagy. As compared to HaCaT keratinocytes treated with siRNA-negative control (siNC), HaCaT keratinocytes treated with Atg5 siRNA (siAtg5) showed significant decreased Atg5 expression, which inhibited LC3-II expression. No significant change of Atg7 expression upon Atg5 silencing was observed, although Atg7 was upregulated under hypoxia (Fig. 2j and Fig. S6D). Respectively, the wound-healing assay and the single-cell motility assay results (Fig. 2k–n, Movie 2) showed the inhibition of cell migration and motility upon Atg5 siRNA treatment without affecting cell proliferation (Fig. S1B). Overall, these results supported the hypothesis that autophagy acts as an important regulator of keratinocyte migration.

BNIP3 promotes keratinocyte migration through the regulation of autophagy

Our previous results have shown that BNIP3 plays an important role in mouse keratinocyte migration under hypoxic conditions6. The potential role of autophagy in BNIP3-regulated keratinocyte migration under hypoxia was investigated by knocking down BNIP3 by small hairpin RNA (shRNA). BNIP3 expression was significantly decreased compared to control empty vector-transduced cells (Fig. 3a). The hypoxia-induced LC3-I conversion into LC3-II was significantly reduced in BNIP3-deficient cells (Fig. 3a and Fig. S7A). As shown in Fig. 3b, hypoxic keratinocytes exhibited a notable increase in the colocalization between LC3-positive autophagosomes and BNIP3 compared to normoxic cells. Loss of BNIP3 significantly abrogated the formation of autophagosomes and the overlapping of LC3 and BNIP3 under hypoxia, thereby indicating the induction of autophagy by BNIP3 in hypoxic keratinocytes.

Fig. 3. BNIP3 promotes keratinocyte migration through regulation of autophagy.

The shBNIP3 stably transfected HaCaT cells and control cells (shNC) were established using lentiviruses. a BNIP3 and LC3 expression levels in the stably transfected HaCaT cells were detected by Western blotting. GAPDH was used as the loading control. b Costaining of LC3 (green) and BNIP3 (red) in HaCaT cells was visualized via confocal microscopy. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar = 25 μm. Single-cell motility assays (c, d) and wound-healing assays (e, f) were performed using the indicated cells. Representative images of wound healing, including keratinocyte trajectories. Scale bar = 100 μm. The results of the quantitative analysis are represented by the mean ± SEM (n = 3). *P < 0.05 vs. Norm group, #P < 0.05 vs. the Hypo group

As expected, no significant changes in normoxic HaCaT keratinocyte migration (Fig. S2A-D, Movie 3) and cell proliferation (Fig. S2E) were noted in BNIP3-deficient cells, which agreed with previous findings in mouse primary keratinocytes6. In addition, loss of BNIP3 greatly impaired hypoxia-enhanced cell motility and migration (Fig. 3c–f, Movie 4). Together, these findings supported the view that autophagy is positively involved in BNIP3-regulated keratinocyte migration under hypoxia.

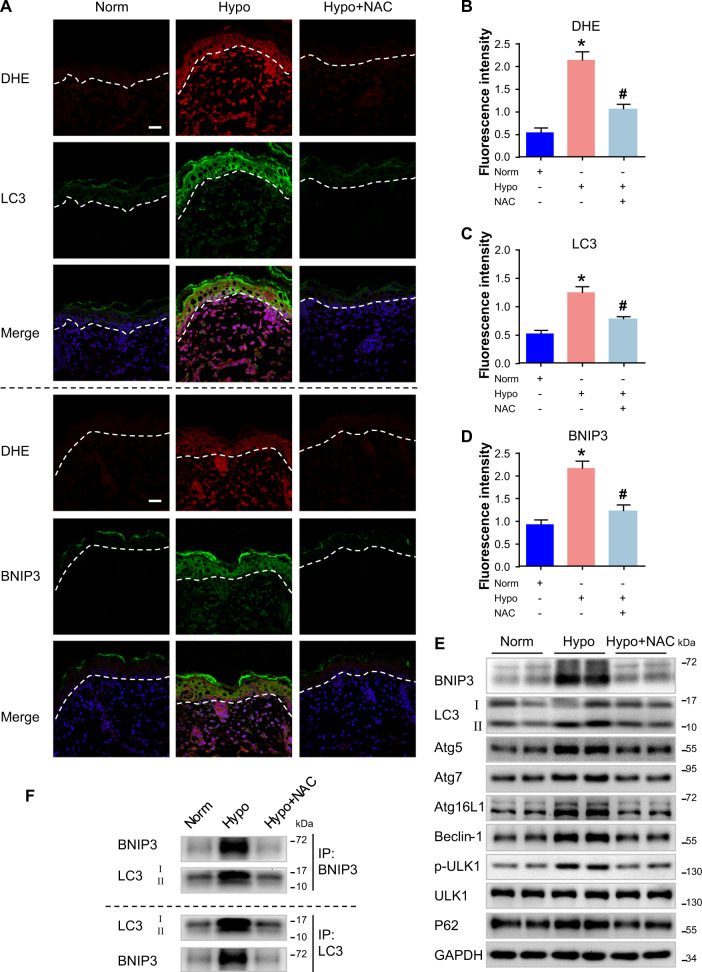

Increased ROS production induced by hypoxia drives epidermal BNIP3 expression in vivo

Wound-induced early production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) is a key regulator of wound healing30. At the early stage after wounding, the wound edge is in a hypoxic state. Thus, the wound-induced increase of ROS might be triggered by a hypoxic microenvironment. To determine if early wound-induced ROS mediates BNIP3 expression and autophagy at the wound, ROS accumulation at wound edge was analyzed by staining using the redox-sensitive fluorescent dye, dihydroethidium (DHE) (Fig. S3). Following wounding, ROS accumulation markedly increased in migrating epidermis at the wound edge (day 5 and day 10), and it decreased to the levels observed in normal skin epidermis when re-epithelialization was fully completed (day 15). The changes of ROS accumulation during wound healing were consistent with that of BNIP3 expression at the wound edge (Fig. 1a, b).

To mimic the hypoxic microenvironment at the wound edge, an in vitro culture model of skin from newborn C57BL/6 mice was generated. Importantly, hypoxia triggered the production of ROS in hypoxic epidermis (Fig. 4a, b). Hypoxia exposure enhanced the formation of autophagosomes in the epidermis as detected by increased LC3 puncta (Fig. 4a–c) and upregulated LC3-II expression (Fig. 4e), which were both attenuated by the addition of the antioxidant, N-acetylcysteine (NAC). Similarly, NAC treatment significantly inhibited hypoxia-induced accumulation of BNIP3 (Fig. 4a–e) and other autophagy-related proteins, including p62, Atg5, Atg7, Atg16L1, Beclin-1, and p-ULK1 (Fig. 4e and Fig. S7B), in the epidermis. These observations suggested that ROS also regulate epidermal autophagy.

Fig. 4. Increased ROS production induced by hypoxia drives epidermal BNIP3 expression in vivo.

Skin specimens from the dorsal coat of newborn mice were cultured in 6-well plates and exposed to hypoxia (2% O2) for 6 h. The N-acetylcysteine (NAC) antioxidant was added 1 h before hypoxia exposure. a After organ culture, skin sections were processed for costaining of dihydroethidine (DHE) and LC3 or BNIP3. Blue signals (DAPI) indicate nuclear staining. Dotted line indicates the boundary between the epidermis and dermis. Scale bars = 25 μm. b–d Graphs indicate the relative fluorescence intensities as determined by ImageJ software. The results are represented by the mean ± SEM (n = 3). *P < 0.05 vs. Norm group, and #P < 0.05 vs. Hypo group. e Western blots were performed to analyze the expression of BNIP3, LC3, P62, Atg5, Atg7, Atg16L1, Beclin-1, and p-ULK1 in cultured skin when subjected to NAC under hypoxia. Representative bands of two samples in each group are shown. GAPDH was used as the loading control. f The indicated cultured skins were lysed in lysis buffer and then immunoprecipitated with anti-BNIP3 or anti-LC3 antibodies followed by immunoblotting with anti-LC3 or anti-BNIP3 antibody

Furthermore, to investigate the role of BNIP3 in the regulation of autophagy in hypoxic epidermis, a co-immunoprecipitation assay was used to analyze the binding effect of BNIP3 with LC3. A strong interaction between BNIP3 and LC3 was found in the hypoxic epidermis, and the addition of NAC remarkably inhibited this interaction (Fig. 4f). Collectively, these results indicated that ROS production induced by hypoxia drives BNIP3 expression and autophagic activity in the epidermis.

BNIP3 upregulation is related to ROS production under hypoxia in vitro

To further confirm the above results, the potential effect of ROS accumulation on epidermal BNIP3 expression in vitro was determined by incubating HaCaT keratinocytes with NAC (5 mM) before hypoxia exposure (2% O2). As expected, NAC significantly attenuated the accumulation of ROS in hypoxic cells (Fig. 5a, b). Notably, western blot analysis and immunofluorescence staining revealed that hypoxia-enhanced BNIP3 expression was impaired upon NAC treatment (Fig. 5c, d and Fig. S8A), which was concomitant with the disturbed autophagosome formation under hypoxia as indicated by downregulation of LC3-II expression (Fig. 5c and Fig. S8A) and decreased LC3 puncta (Fig. 5e). Furthermore, the wound-healing assay and single-cell motility assay demonstrated that addition of NAC markedly reduced the migration and motility of HaCaT keratinocytes (Fig. 5f–h, Movie 5). As shown in Fig. S1C, cell proliferation remained unaffected by NAC under hypoxic conditions, suggesting that ROS plays a positive role in regulating cell migratory capacities, which was in line with a previous report31. Moreover, hypoxia-enhanced phosphorylation of p38 and JNK was downregulated upon NAC treatment (Fig. 5c), which was concomitant with the changes in cellular behavior mentioned above. Taken together with the results shown in Fig. 4, these findings suggested that hypoxia exposure results in ROS accumulation, which stimulates BNIP3 expression in keratinocytes. In addition, these data demonstrated that ROS also regulate p38 and JNK MAPK in keratinocytes.

Fig. 5. BNIP3 upregulation is related to ROS production under hypoxia in vitro.

HaCaT cells were subjected to hypoxia for 6 h. NAC was added 1 h before hypoxia exposure. a After hypoxia exposure, HaCaT cells were processed for immunostaining of DHE. Blue signals (DAPI) indicate nuclear staining, and representative images are shown. Scale bar = 100 μm. b Graphs indicate the relative fluorescence intensities in a as determined by ImageJ software. The results are represented by the mean ± SEM (n = 3). *P < 0.05 vs. Norm group, and #P < 0.05 vs. Hypo group. c Western blots were performed to analyze the expression of BNIP3 and LC3 as well as activities of p38/MAPK and JNK/MAPK in HaCaT cells subjected to NAC under hypoxia. HIF-1α was used as an indicator of hypoxia. GAPDH was used as the loading control. Immunostaining of BNIP3 (d) and LC3 (e) in indicated HaCaT cells. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Scale bar = 25 μm. f–h Wound-healing assays and single-cell motility assays were performed using indicated cells. Representative images of wound healing, including keratinocyte trajectories. Scale bar = 100 μm. The results of the quantitative analysis are represented by the mean ± SEM (n = 3). *P < 0.05 vs. Norm group, and #P < 0.05 vs. the Hypo group

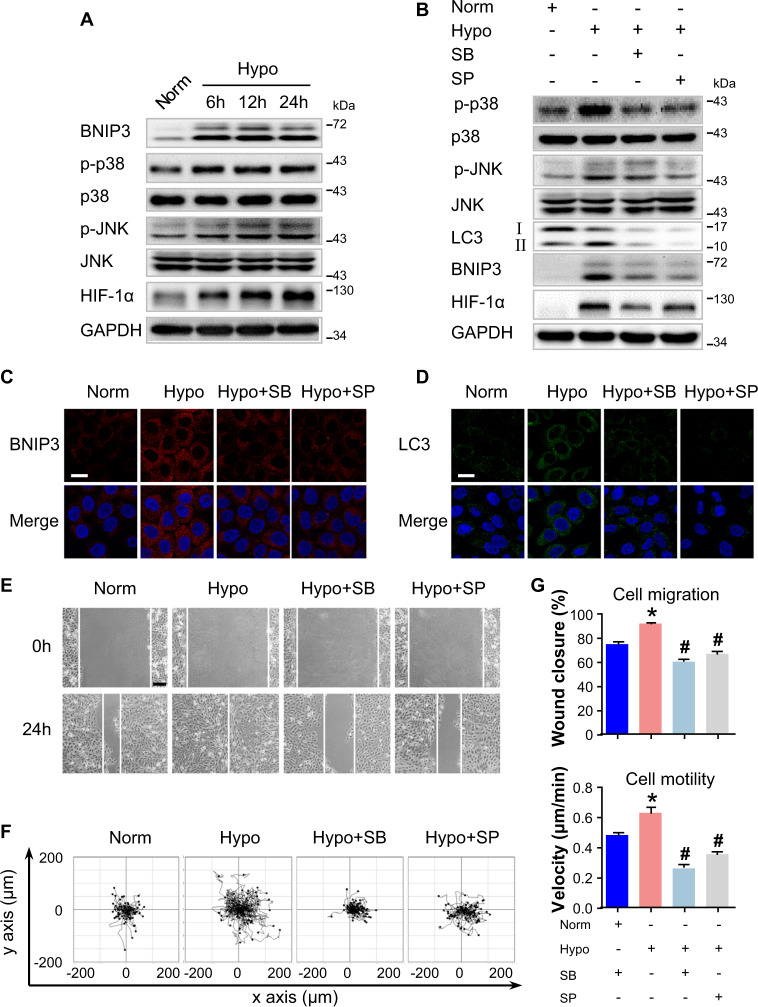

BNIP3 expression is regulated by p38 and JNK MAPK under hypoxia

As was reported previously that p38 and JNK MAPK signaling pathway were responsible for cell migration32,33, we studied the phosphorylation of p38 and JNK in hypoxic keratinocytes. As shown in Fig. 6a and Fig. S8B, western blot analysis showed that levels of p38 and JNK phosphorylation significantly increased in HaCaT keratinocytes upon hypoxia exposure. These results indicated that hypoxia activates the p38 and JNK MAPK signaling in keratinocytes. Previous studies have reported that BNIP3 expression is regulated by the MAPK signaling under different cellular contexts13,34. Therefore, to determine if the increased BNIP3 expression observed in keratinocytes upon hypoxia is mediated by p38 and JNK, HaCaT keratinocytes were incubated with the specific MAPK inhibitors, SB203580 (SB, a p38 inhibitor, 5 μM) and SP600125 (SP, a JNK inhibitor, 5 μM), followed by hypoxic treatment and then Western blot analysis. Both SB and SP significantly reduced the hypoxia-induced BNIP3 expression, concomitant with LC3-II downregulation and decreased LC3 puncta (Fig. 6b–d, and Fig. S8C), suggesting that p38 and JNK have a crucial role in BNIP3 expression and the regulation of autophagy in hypoxic keratinocytes. In addition, the scratched wound-healing assay and the single-cell motility assay showed a notable decrease in hypoxia-induced cell migration and motility when keratinocytes were treated with the above specific MAPK inhibitors (Fig. 6e–g, Movie 6). As shown in Fig. S1D, cell proliferation remained unaffected by MAPK inhibitors without hypoxic treatment, suggesting that hypoxia-induced BNIP3 expression mediated by p38 and JNK MAPK is important for cell migration upon hypoxia. Furthermore, SP, the JNK inhibitor, inhibited not only the JNK MAPK signaling as detected by the downregulation of its phosphorylation level but also the p38 MAPK signaling (Fig. 6b). These data suggested that JNK MAPK regulates and cooperates with p38 MAPK to elevate BNIP3 expression in response to hypoxic treatment.

Fig. 6. BNIP3 expression is regulated by p38 and JNK under hypoxia.

a HaCaT cells were exposed to hypoxia (2%) and incubated for the indicated times, and total proteins were harvested for detection of the expression of BNIP3 and the activities of p38/MAPK and JNK/MAPK. HIF-1α was used as an indicator of hypoxia. GAPDH was used as the loading control. b–e HaCaT cells were exposed to hypoxia (2%) for 6 h. The SB203580 (SB, 5 μM) and SP600125 (SP, 5 μM) MAPK inhibitors were added 1 h before hypoxia exposure. b The extracted proteins were then immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. HIF-1α was used as an indicator of hypoxia. GAPDH was used as the loading control. Fluorescence staining of BNIP3 (c), and LC3 expression (d) in HaCaT cells are shown. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Scale bar = 25 μm. e Wound-healing assays and f single-cell motility assays were performed using the indicated cells. Representative images of wound healing, including keratinocyte trajectories. Scale bar = 100 μm. The results of quantitative analysis (g) are represented by the mean ± SEM (n = 3). *P < 0.05 vs. Norm group, and #P < 0.05 vs. Hypo group

Discussion

BNIP3 is a pro-apoptotic atypical BH3-only protein that has been reported to induce apoptosis, necrosis, or autophagy depending on the cellular context35. We have previously determined that BNIP3 is important in the re-epithelialization step during wound healing. BNIP3 silencing markedly impairs mouse epidermal cell migration under hypoxia in vitro6. Others have demonstrated that aberrant BNIP3 expression promotes tumor invasion and metastasis in various epithelial cancers36–38. Despite the evident role of BNIP3 in cell migration, the underlying mechanisms in which BNIP3 regulates cell migration are still largely unknown.

The present study demonstrated that expression levels of BNIP3 and other hallmarks of autophagy were significantly elevated in migrating epidermis. Moreover, the interaction between BNIP3 and LC3 was remarkably elevated during wound healing. These observations indicated the potential role of BNIP3 in autophagy regulation during wound healing. Generally, hypoxia occurs immediately after wounding and is triggered by vascular disruption and increased oxygen consumption at the wound edge. Thus, the migrating epidermis is in a hypoxic microenvironment, which may lead to the upregulation of BNIP3 and autophagy. Further results demonstrated that hypoxia exposure markedly stimulated autophagy and BNIP3 expression as well as the colocalization of BNIP3 and LC3 in human HaCaT keratinocytes. Inhibition of keratinocyte autophagy greatly attenuated the hypoxia-induced cell migration, suggesting the positive role of autophagy in cell migration. Furthermore, silencing of BNIP3 significantly impaired hypoxia-enhanced cell autophagy, motility, and migration similar to its role in mouse epidermal cells6. Thus, the significant impairment of cell migration and motility following autophagy inhibition indicated that BNIP3-induced autophagy is indispensable for cell migration and motility. These findings provided the first link between BNIP3-induced autophagy and keratinocyte migration, which is crucial for the reformation of the epidermal barrier after wounding.

Growing evidence has suggested that autophagy plays an important role in cell in various physiological and pathophysiological situations. The present data demonstrated that BNIP3-induced autophagy stimulates keratinocyte migration in two different migration assays, namely, the wound-healing assay and the single-cell motility assay. However, the mechanisms underlying how BNIP3-induced autophagy promotes hypoxia-induced keratinocyte migration are still unknown. Autophagy, as an important nonselective degradation machinery, regulates focal adhesion disassembly, β1 integrin membrane recycling, and acquisition of mesenchymal markers, which are crucial for cell migration8,10,11,39,40. Mitochondria are a potential target of hypoxia-induced autophagy, and the dynamics of mitochondria define the energy supply to reorganize the cytoskeleton and sustain cell movement41. BNIP3 is engaged in mitophagy (one of the components of selective autophagy) via the interaction of mitochondria with autophagosome ATG8 proteins (LC3 and GABARAP)42. Recently, BNIP3 has been shown to mediatemitophagy during keratinocyte differentiation12. Ablation of BNIP3 induces the reduction of lamellipodia and filopodia formation as well as the migratory capacity of melanoma cells43. Moreover, silencing of Cadherin-6, which is a BNIP3 interactor in thyroid cancer cells, causes a profound reorganization of cytoskeleton with a marked reduction of cell surface protrusions and reversion of the epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) phenotype44. These data suggest that BNIP3 may regulate hypoxia-induced keratinocyte migration through a nonselective or selective autophagy-dependent manner. Therefore, it would be interesting to determine if the nonselective and selective forms of autophagy have complementary roles during cell migration. Further analysis will be required to confirm this hypothesis.

ROS activate several signal transduction cascades and have been implicated as important mediators of hypoxia45. The present study investigated the role of ROS in BNIP3 expression. In line with prior reports, the present findings indicated that ROS accumulate in the wound edge30. An ex vivo skin culture model with hypoxia treatment to mimic the wound-induced hypoxic microenvironment demonstrated increased ROS production, BNIP3 expression, autophagy activation and interaction between BNIP3 and LC3 in the skin model, which were all abrogated by the addition of NAC. These data demonstrated the positive role of ROS in BNIP3 expression and autophagy activation, and this role was further confirmed using hypoxic HaCaT keratinocytes. Moreover, ROS accumulation facilitated hypoxia-induced keratinocyte migration but had no effect on cell proliferation. These results agreed with similar reported cases in which early production of ROS at the leading edge of the wound integrates early wound signals for efficient wound repair46,47. These findings highlighted the importance of early signaling events, including ROS accumulation, during wound repair.

To determine the downstream mechanisms by which ROS mediates the effect of BNIP3 on autophagy and keratinocyte migration, the potential involvement of the MAPK signaling pathway was assessed. Notably, the addition of NAC attenuated the hypoxia-induced activation of p38 and JNK signaling. In addition, a marked reduction of hypoxia-induced BNIP3 expression was found with a concomitant inhibition of autophagy activation and cell migration in hypoxic keratinocytes treated with the specific MAPK inhibitors, SB203580 and SP600125. The present data implied that hypoxia-elevated BNIP3 expression and autophagy activation are triggered by ROS accumulation in a MAPK-dependent pathway. However, the mechanism that facilitates MAPK pathways to regulate BNIP3 expression in hypoxic keratinocytes is currently unknown. BNIP3 expression is mainly regulated by hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α), which is a major transcription factor in hypoxia and controls the expression of a series of genes35. Consistent with previous reports, the present study found that HIF-1α pathway was activated when ROS upregulated BNIP3 expression in hypoxic keratinocytes and that the addition of MAPK inhibitors reversed the hypoxia-induced activation of HIF-1. Moreover, suppression of HIF-1α pathway by small-interfering RNAs significantly inhibited hypoxia-induced BNIP3 expression. Because the HIF-1α pathway can be regulated by MAPK signaling, we speculate that it acts as a mediator of ROS-mediated MAPK signaling in the regulation of BNIP3 expression. Moreover, several studies have reported HIF-1α−independent mechanisms for the regulation of BNIP3 expression. For instance, BNIP3 expression is regulated by forkhead box (FOX)O transcription factor, which has been reported to be activated by the p38 and JNK pathway14,16,48. Further mechanistic analyses will be required to address these issues in keratinocytes in response to hypoxia exposure.

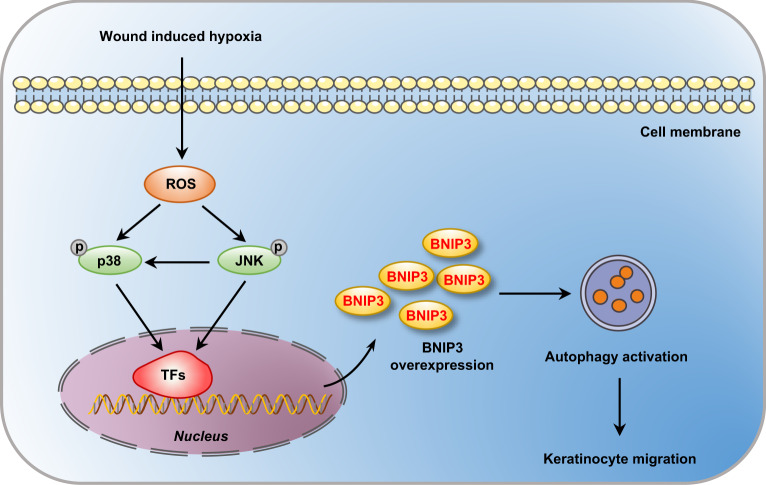

The present findings revealed that BNIP3-induced autophagy occurs via hypoxia-stimulated ROS-mediated activation of p38 and JNK MAPK signaling and that it is critical for the migration of keratinocytes during wound repair (Fig. 7). These findings provide new insights into the functions of BNIP3 in epidermal wound healing, and these data highlight potential targets for therapeutic interventions.

Fig. 7. Schematic illustrating that BNIP3 promotes keratinocyte migration through autophagy activation.

Wound-induced hypoxia in the wound margin stimulates the accumulation of ROS, which in turn increases the phosphorylation of p38 and JNK MAP kinase. Activated MAP kinases promote the upregulation of transcription factor (TF) signaling, such as HIF-1α and FOXO, elevating the expression of BNIP3 and resulting in the induction of autophagy. Further, autophagy is required for the migration of keratinocytes

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The present work was supported by the State Key Development Program for Basic Research of China (2017YFC1103302), the Key Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (81430042), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NO. 81601683).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by J. Martinez

This article has been retracted. Please see the retraction notice for more detail: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-024-06709-3

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

5/6/2024

This article has been retracted. Please see the Retraction Notice for more detail: 10.1038/s41419-024-06709-3

Change history

4/1/2019

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41419-019-1533-1

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at (10.1038/s41419-019-1473-9).

References

- 1.Ruthenborg RJ, Ban JJ, Wazir A, Takeda N, Kim JW. Regulation of wound healing and fibrosis by hypoxia and hypoxia-inducible factor-1. Mol. Cells. 2014;37:637–643. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2014.0150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guo S, Dipietro LA. Factors affecting wound healing. J. Dent. Res. 2010;89:219–229. doi: 10.1177/0022034509359125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Velnar T, Bailey T, Smrkolj V. The wound healing process: an overview of the cellular and molecular mechanisms. J. Int. Med. Res. 2009;37:1528–1542. doi: 10.1177/147323000903700531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodriguez PG, Felix FN, Woodley DT, Shim EK. The role of oxygen in wound healing: a review of the literature. Dermatol. Surg. 2008;34:1159–1169. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.34254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Toole EA, van Koningsveld R, Chen M, Woodley DT. Hypoxia induces epidermal keratinocyte matrix metalloproteinase-9 secretion via the protein kinase C pathway. J. Cell. Physiol. 2008;214:47–55. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang J, et al. BNIP3 promotes the motility and migration of keratinocyte under hypoxia. Exp. Dermatol. 2017;26:416–422. doi: 10.1111/exd.13248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamacher-Brady, A. et al. Response to myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury involves Bnip3 and autophagy. Cell Death Differ.14, 146–157 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Kenific CM, Wittmann T. Autophagy in adhesion and migration. J. Cell Sci. 2016;129:3685–3693. doi: 10.1242/jcs.188490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maiuri MC, Zalckvar E, Kimchi A, Kroemer G. Self-eating and self-killing: crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:741–752. doi: 10.1038/nrm2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun T, Jiao L, Wang Y, Yu Y, Ming L. SIRT1 induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition by promoting autophagic degradation of E-cadherin in melanoma cells. Cell death Dis. 2018;9:136. doi: 10.1038/s41419-017-0167-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharifi MN, et al. Autophagy promotes focal adhesion disassembly and cell motility of metastatic tumor cells through the direct interaction of paxillin with LC3. Cell Rep. 2016;15:1660–1672. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.04.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moriyama M, et al. BNIP3 plays crucial roles in the differentiation and maintenance of epidermal keratinocytes. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2014;134:1627–1635. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moriyama M, et al. BNIP3 upregulation via stimulation of ERK and JNK activity is required for the protection of keratinocytes from UVB-induced apoptosis. Cell death Dis. 2017;8:e2576. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin A, et al. The FoxO-BNIP3 axis exerts a unique regulation of mTORC1 and cell survival under energy stress. Oncogene. 2014;33:3183–3194. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang EY, et al. p53 mediates autophagy and cell death by a mechanism contingent on Bnip3. Hypertension. 2013;62:70–77. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chaanine AH, et al. JNK modulates FOXO3a for the expression of the mitochondrial death and mitophagy marker BNIP3 in pathological hypertrophy and in heart failure. Cell death Dis. 2012;3:265. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2012.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalas, W., Swiderek, E., Rapak, A., Kopij, M., Rak, J. & Strzadala, L. H-ras up-regulates expression of BNIP3. Anticancer Res.31, 2869–2875 (2011). [PubMed]

- 18.Atay O, Skotheim JM. Spatial and temporal signal processing and decision making by MAPK pathways. J. Cell Biol. 2017;216:317–330. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201609124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peluso I., Yarla N. S., Ambra R., Pastore G., Perry G. MAPK signalling pathway in cancers: Olive products as cancer preventive and therapeutic agents. Semin. cancer biol. 2017. pii: S1044-579X(17)30165-7. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2017.09.002. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Munshi A, Ramesh R. Mitogen-activated protein kinases and their role in radiation response. Genes Cancer. 2013;4:401–408. doi: 10.1177/1947601913485414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim EK, Choi EJ. Compromised MAPK signaling in human diseases: an update. Arch. Toxicol. 2015;89:867–882. doi: 10.1007/s00204-015-1472-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kashiwagi M, Kuroki T, Huh N. Specific inhibition of hair follicle formation by epidermal growth factor in an organ culture of developing mouse skin. Dev Biol.189, 22–32 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Moriyama M, Osawa M, Mak SS, Ohtsuka T, Yamamoto N, Han H, et al. Notch signaling via Hes1 transcription factor maintains survival of melanoblasts and melanocyte stem cells. J. Cell Biol.173, 333–339 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Huang Y, Zhou J, Luo S, Wang Y, He J, Luo P, et al. Identification of a fluorescent small-molecule enhancer for therapeutic autophagy in colorectal cancer by targeting mitochondrial protein translocase TIM44. Gut.67, 307–319 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Tang D, et al. Notch1 signaling contributes to hypoxia-induced high expression of integrin beta1 in keratinocyte migration. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:43926. doi: 10.1038/srep43926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang J, Yang Z, Dong J. P62: An emerging oncotarget for osteolytic metastasis. J. Bone Oncol. 2016;5:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jbo.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duran A, et al. The signaling adaptor p62 is an important NF-κB mediator in tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:343–354. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu JX, Zhang DG, Zheng JN, Pei DS. Rap2a is a novel target gene of p53 and regulates cancer cell migration and invasion. Cell. Signal. 2015;27:1198–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2015.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pasquier B. Autophagy inhibitors. Cell. Mol. life Sci. 2016;73:985–1001. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-2104-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.LeBert D., Squirrell J. M. Damage-induced reactive oxygen species regulate vimentin and dynamic collagen-based projections to mediate wound repair. Elife. 7, 1–26, pii: e30703. (2018). 10.7554/eLife.30703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Guo X, et al. The galvanotactic migration of keratinocytes is enhanced by hypoxic preconditioning. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:10289. doi: 10.1038/srep10289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang X, et al. Hypoxia regulates CD9-mediated keratinocyte migration via the P38/MAPK pathway. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:6304. doi: 10.1038/srep06304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang J, et al. CD9 is critical for cutaneous wound healing through JNK signaling. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2012;132:226–236. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang B, et al. BNIP3 upregulation by ERK and JNK mediates cadmium-induced necrosis in neuronal cells. Toxicol. Sci. 2014;140:393–402. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfu091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang J, Ney PA. Role of BNIP3 and NIX in cell death, autophagy, and mitophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:939–946. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thongchot S, et al. High expression of HIF-1alpha, BNIP3 and PI3KC3: hypoxia-induced autophagy predicts cholangiocarcinoma survival and metastasis. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2014;15:5873–5878. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.14.5873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Giatromanolaki A, et al. BNIP3 expression is linked with hypoxia-regulated protein expression and with poor prognosis innonsmall cell lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004;10:5566–5571. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vijayalingam S, et al. Overexpression of BH3-only protein BNIP3 leads to enhanced tumor growth. Genes cancer. 2010;1:964–971. doi: 10.1177/1947601910386110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu H, Ma Y, He HW, Zhao WL, Shao RG. SPHK1 (sphingosine kinase 1) induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition by promoting the autophagy-linked lysosomal degradation of CDH1/E-cadherin in hepatoma cells. Autophagy. 2017;13:900–913. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2017.1291479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tuloup-Minguez V, et al. Autophagy modulates cell migration and beta1 integrin membrane recycling. Cell Cycle. 2013;12:3317–3328. doi: 10.4161/cc.26298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gugnoni M, Sancisi V, Manzotti G, Gandolfi G, Ciarrocchi A. Autophagy and epithelial-mesenchymal transition: an intricate interplay in cancer. Cell death Dis. 2016;7:e2520. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Quinsay MN, Thomas RL, Lee Y, Gustafsson AringB. Bnip3-mediated mitochondrial autophagy is independent of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Autophagy. 2010;6:855–862. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.7.13005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maes H, et al. BNIP3 supports melanoma cell migration and vasculogenic mimicry by orchestrating the actin cytoskeleton. Cell death Dis. 2014;5:e1127. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gugnoni M, et al. Cadherin-6 promotes EMT and cancer metastasis by restraining autophagy. Oncogene. 2017;36:667–677. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith KA, Waypa GB, Schumacker PT. Redox signaling during hypoxia in mammalian cells. Redox Biol. 2017;13:228–234. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Love NR, et al. Amputation-induced reactive oxygen species are required for successful Xenopus tadpole tail regeneration. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013;15:222. doi: 10.1038/ncb2659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gauron C, et al. Sustained production of ROS triggers compensatory proliferation and is required for regeneration to proceed. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:2084. doi: 10.1038/srep02084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou Y. Y., Li Y., Jiang W. Q. & Zhou L. F. MAPK/JNK signalling: a potential autophagy regulation pathway. Biosci. Rep. 35, pii: e00199 (2015). 10.1042/BSR20140141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.