Abstract

Background

To determine the relation between daily glycemic fluturation and the intestinal mucosal barrier dysfunction in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

Methods

Totally 66 patients with T2DM were enrolled, 33 healthy volunteers were also recruited according to the enrolled patients’ gender and age in a ratio of 2: 1. Patients were bisected by the median of endotoxins level into low(< 12.31 μ/l, n = 33) and high(≥12.31 μ/l, n = 33) blood endotoxin groups. Clinical data and blood glucose fluctuations were compared between groups. Multivariate regression analysis was used to determine the independent factors affecting the intestinal mucosal barrier.

Results

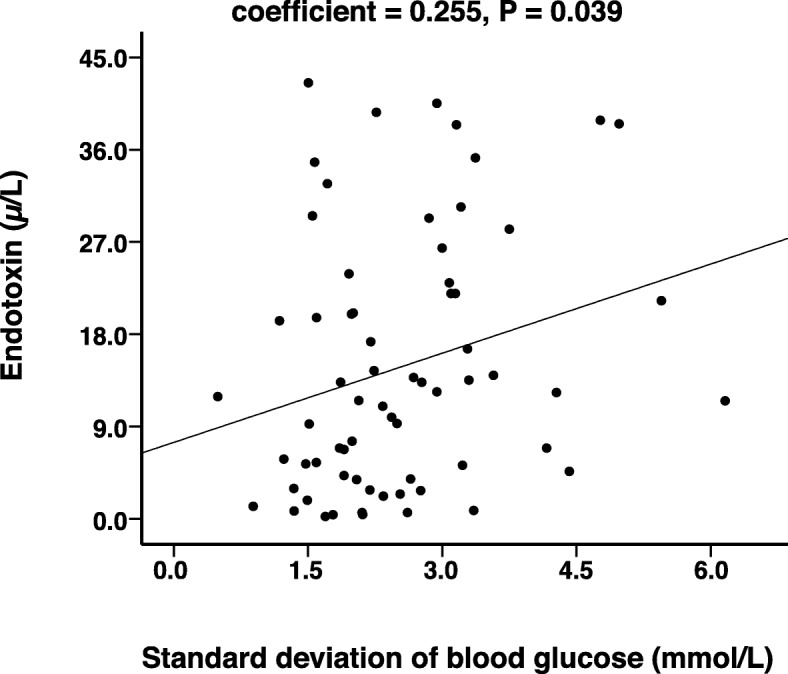

Serum endotoxin [12.1 (4.2~22.0) vs 3.2 (1.3~6.0), P < 0.001] and fasting blood glucose levels [9.8 ± 3.6 vs 5.4 ± 0.7, P < 0.001] were significantly higher in patients with T2DM than the control group. The standard deviation of blood glucose (SDBG) within 1 day [2.9 (2.0~3.3) vs. 2.1 (1.6~2.5), P = 0.012] and the largest amplitude of glycemic excursions (LAGE) [7.5 (5.4~8.9) vs. 5.9 (4.3~7.4), P = 0.034] were higher in the high endotoxin group than in the low endotoxin group. A multiple linear stepwise regression revealed a positive correlation between SDBG with endotoxin (standard partial regression coefficient = 0.255, P = 0.039).

Conclusions

T2DM patients who incapable of maintaining stable blood glucose level are at a higher risk to associated with intestinal mucosal barrier injury.

Keywords: Type 2 diabetes mellitus, Intestinal mucosal barrier, Endotoxin, Blood glucose volatility, Intestinal permeability

Background

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a long-term metabolic disorder caused by both genetic and environmental factors. The defects in insulin secretion or function (or both) can cause disorder in carbohydrates, proteins, fats, electrolytes, and water metabolism [1–3]. It is clinically characterized by chronic persistent hyperglycemia and high volatility. T2DM patients also tend to be associated with a series of chronic complications, such as nerve, blood vessel and gastrointestinal tract defects including intestinal mucosal barrier damage, seriously affecting the life quality [4, 5]. According to the latest statistics from the National Vital Statistics System, diabetes is the seventh of the top ten causes of death in the United States in 2016 [6].

The intestine is an important organ that should not be omitted during the treatment of DM [7–9]. The intestinal mucosal barrier prevents the translocation of bacteria and endotoxins into blood and lymph circulatory systems under normal physiological conditions. Dysregulation of intestinal mucosal barrier function would increase the permeability to the intestinal pathogens and endotoxins, which cause infection or inflammation [10, 11]. Previous studies suggested that the low-grade inflammatory state of patients with T2DM was possibily related to intestinal endotoxin [12, 13]. On the other hand, disorder of intestinal microflora composition is associated with the intestinal mucosal barrier damages [14, 15], which leads to nonspecific inflammatory, and in turn aggravates insulin resistance and T2DM metabolism disorders through the NF-κB pathway and JNK signal transduction pathway [16–18]. Therefore, the intestinal mucosal barrier function of patients with T2DM should be carefully monitored.

Currently, levels of the serum D-lactic acid, diamine oxidase (DAO), and endotoxin, which reflect the permeability of intestinal mucosa and bacterial translocation, are used to determine the intestinal mucosal barrier function in clinical practice [19, 20]. For patients with T2DM, glycemic monitoring (including short- and long-term blood glucose level fluctuations, as well as average blood glucose levels) is substantial. Studies have shown that persistent hyperglycemia can lead to intestinal mucosal barrier damage [5], however, the relationship between fluctuation of blood glucose level and intestinal mucosal barrier damage remains unclear. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the relationship between glycemic control and intestinal mucosal barrier dysfunction in patients with T2DM.

Methods

Subjects

We recruited 66 patients diagnosed with T2DM from September 2017 to June 2018. All patients included in the study met the diagnostic criteria of the 2018 AACE/ACE Consensus Statement: Comprehensive Management of T2DM [21]. And their eating pattern were controlled according to the suggestion of ‘Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes’ in 2014 [22]. The control group was composed of 33 healthy volunteers who were recruited in a 2:1 ratio according to the patients’ sex and age. All subjects with digestive diseases, chronic malnutrition, malignant tumors, and intestinal infections which can inhibit the intestinal mucosal barrier function within 2 weeks were excluded.

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Review Board of Jiading District Central Hospital (2017-ZD-03). All subjects were anonymized. All subjects signed informed consent form.

Study methods

For all subjects included, the fasting venous blood sample was collected, the fasting blood glucose was examined, and the functionality of intestinal mucosal barrier of subjects were determined by the serum D-lactic acid, DAO, and endotoxin. Patients with T2DM were further divided into the low-value group (< 12.31u/l, n = 33) and high-value group (≥12.31u/l, n = 33) based on the median endotoxin levels. For the patients with T2DM, clinical characteristic were collected [DM duration, body mass index (BMI), history of hypertension, use of drugs (such as insulin and metformin etc.), smoking history, and family history of DM]. The abnormal fasting blood glucose, 2 h blood glucose level after breakfast, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), and glycated albumin (GA) of patients were also examined at the first day of enrollment. The daily blood glucose level (before breakfast (A), 2 h after breakfast (B), before lunch (C), 2 h after lunch (D), before dinner (E), 2 h after dinner (F), and before sleep (G)) was monitered by active blood glucose meter (Accu-Chek®, Germany) using the finger capillary blood samples. Short-term glycemic excursions, including the magnitude of postprandial glucose excursion (PPGE), the largest amplitude of glycemic excursions (LAGE), and the standard deviation of blood glucose (SDBG) within 1 day were calculated by:

PPGE = ;

LAGE = D (maximum glycemic value) - A (minimum glycemic value);

SDBG =;

X (glycemic average within 1 day) = .

Functionality of the intestinal mucosal barrier

The functionality of the intestinal mucosal barrier was determined using the DAO/lactic acid/bacterial endotoxin combined test kit (enzymatic method; Beijing Zhongsheng Jinyu Diagnostic Technology Co., Ltd.), supporting by the JY-DLT intestinal barrier function biochemical indicator analysis system. The experiments were undergone according to the protocols suggested by the manufacturer and conducted within 4 h after serum extraction.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done using the SPSS 19.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Normally distributed data were expressed in mean ± standard deviations (SD) and compared using Student’s t test; otherwise was indicated as Median (Q1~Q3) and compared using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test. Numerical data were expressed in frequency and compared using χ2 test. Multiple logistic regression was conducted to identify the factors that influenced the functionality of intestinal mucosal barrier. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The serum endotoxin [12.1(4.2~22.0) vs 3.2(1.3~6.0), P < 0.001] and FPG [(9.8 ± 3.6) vs (5.4 ± 0.7), P < 0.001] in patients with T2DM were significantly higher than those in the control group. No significant difference was observed in DAO and D-lactic acid (Table 1).

Table 1.

Background characteristics of particippants

| Control groups (n = 33) | T2DM (n = 66) | Statistics | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male [n(%)] | 19 (57.6) | 38 (57.6) | – | 1.000 |

| Age [(Mean ± SD), years] | 61.2 ± 9.6 | 60.9 ± 11.8 | t = 0.121 | 0.904 |

| BMI [(Mean ± SD), Kg/M2] | 26.5 ± 5.8 | 25.1 ± 3.9 | t = 1.417 | 0.160 |

| Smoking [n(%)] | 13 (39.4) | 16 (24.2) | x2 = 2.438 | 0.118 |

| Hypertension [n(%)] | 16 (48.5) | 40 (60.6) | x2 = 1.316 | 0.251 |

| Diabetes history [(Mean ± SD), years] | NA | 6.0 (1–14) | – | – |

| Diabetic complication [n(%)] | NA | 31 (46.9) | – | – |

| Medications [n(%)] | ||||

| Insulin | NA | 21 (31.8) | – | – |

| Metformin | NA | 32 (48.5) | – | – |

| α-glucosidase inhibitor | NA | 29 (43.9) | – | – |

| sulfonylureas | NA | 9 (13.6) | – | – |

| glinide | NA | 5 (7.6) | – | – |

| DPP-4 inhibitor | NA | 1 (1.5) | – | – |

| Laboratory data | ||||

| HbAlc [M(Q1~Q3), %] | 5.2 (4.9~5.6) | 9.3 (7.4~11.0) | z = −7.340 | < 0.001 |

| GA [M(Q1~Q3), %] | 14.1 (13.3~14.8) | 23.5 (19.4~28.5) | z = −6.751 | < 0.001 |

| Creatinine [M(Q1~Q3), μmol/L] | 76 (64.5~83) | 65 (54.5~80) | z = −1.620 | 0.105 |

| GFR [M(Q1~Q3), ml/min] | 90.3 (83.7~98.8) | 94.9 (78.1~104.1) | z = − 0.672 | 0.502 |

| hs-CRP [M(Q1~Q3), ng/L] | 3 (1.5~6.7) | 3.5 (1.2~18.9) | z = −0.801 | 0.423 |

| Index of the intestinal mucosal barrier | ||||

| DAO [M(Q1~Q3), u/l] | 6.7 (5.4~9.3) | 5.9 (4.1~9.6) | z = −1.413 | 0.158 |

| D-lactic acid [M(Q1~Q3), mg/l] | 49.0 (43.1~53.3) | 47.0 (37.2~54.8) | z = −0.572 | 0.567 |

| Endotoxins [M(Q1~Q3), μ/l] | 3.2 (1.3~6.0) | 12.1 (4.2~22.0) | z = −4.315 | < 0.001 |

| FPG[(Mean ± SD), mmol/l] | 5.4 ± 0.7 | 9.8 ± 3.6 | t = −9.070 | < 0.001 |

HbAlc Glycosylated hemoglobin, GA glycated albumin, GFR Glomerular filtration rate, DAO diamine oxidase, hs-CRP high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, FPG:Fasting Plasma Glucose

Clinical charateristics comparation between high- and low-endotoxin groups

The SDBG [2.9(2.0~3.3) vs 2.1(1.6~2.5), P = 0.012] and LAGE [7.5(5.4~8.9) vs 5.9(4.3~7.4), P = 0.034] in the high endotoxin group were higher than those in the low endotoxin group. No significant difference was observed in the other indicators (all P > 0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Between the two groups of clinical data and glucose control comparison

| Low groups (< 12.31u/l, n = 33) | High groups (12.31 ≥ u/l, n = 33) | Statistics | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male [n(%)] | 16 (48.5) | 22 (66.7) | x2 = 2.233 | 0.135 |

| Age [(Mean ± SD), years] | 62.3 ± 11.1 | 59.5 ± 12.5 | t = 0.990 | 0.326 |

| Hypertension [n(%)] | 21 (63.6) | 19 (57.6) | x2 = 0.254 | 0.614 |

| Smoking [n(%)] | 5 (15.2) | 11 (33.3) | x2 = 2.970 | 0.085 |

| Positive family history [n(%)] | 7 (21.2) | 7 (21.2) | – | 1.000 |

| BMI [(Mean ± SD), Kg/M2] | 25.0 ± 4.4 | 25.2 ± 3.4 | t = − 0.176 | 0.861 |

| Diabetes history [(Mean ± SD), mouth] | 9.0 (2~15.5) | 5.0 (1.0~10.0) | z = −1.649 | 0.099 |

| hs-CRP [M(Q1~Q3), mmol/l] | 2.1 (0.5~6.6) | 1.8 (0.5~6.7) | z = −0.250 | 0.802 |

| Medications [n(%)] | ||||

| Insulin | 11.0 (33.3) | 10.0 (30.3) | x2 = 0.070 | 0.792 |

| Metformin | 17.0 (51.5) | 15.0 (45.5) | x2 = 0.243 | 0.622 |

| α-glucosidase inhibitor | 12.0 (36.4) | 17.0 (51.5) | x2 = 1.538 | 0.215 |

| Sulfonylureas | 2.0 (6.1) | 7.0 (21.2) | – | 0.149 |

| Glinide | 1.0 (3.0) | 4.0 (12.1) | – | 0.355 |

| DPP-4 inhibitor | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.0) | – | 1.000 |

| Glucose control data | ||||

| FPG [M(Q1~Q3), mmol/l] | 8.6 (6.8~12.9) | 8.8 (7.5~11.1) | z = − 0.023 | 0.982 |

| 2h PBG [M(Q1~Q3), mmol/l] | 12.8 (10.6~18.1) | 17.0 (15.2~20.8) | z = − 1.858 | 0.063 |

| DGA [M(Q1~Q3), mmol/l] | 11.0 (9.0~15.0) | 11.9 (10.1~13.7) | z = − 0.301 | 0.763 |

| HbAlc [M(Q1~Q3), %] | 9.2 (8.2~10.5) | 8.2 (8.2~9.4) | z = − 1.320 | 0.187 |

| GA [M(Q1~Q3), %] | 23.3 (19.3~27.2) | 25.8 (20.0~36.3) | z = − 1.247 | 0.212 |

| Glucose fluctuations of Short-term | ||||

| SDBG [M(Q1~Q3), mmol/l] | 2.1 (1.6~2.5) | 2.9 (2.0~3.3) | z = − 2.520 | 0.012 |

| PPGE [M(Q1~Q3), mmol/l] | 2.8 (1.8~3.1) | 2.2 (1.9~3.8) | z = − 0.917 | 0.359 |

| LAGE [M(Q1~Q3), mmol/l] | 5.9 (4.3~7.4) | 7.5 (5.4~8.9) | z = − 2.123 | 0.034 |

| SDBG < 2.0 mmol/l [n(%)] | 15.0 (45.5) | 9.0 (27.3) | x2 = 2.357 | 0.125 |

| PPGE < 2.2 mmol/l [n(%)] | 15.0 (45.5) | 11.0 (33.3) | x2 = 1.015 | 0.314 |

| LAGE< 4.4 mmol/l [n(%)] | 9.0 (27.3) | 4.0 (12.1) | x2 = 2.395 | 0.122 |

DGA Daily glucose average,FPG:Fasting Plasma Glucose, PBG:Postprandial Blood Glucose, SDBG Standard Deviation Of Blood Glucose, PPGE Postprandial Glucose Excursion, LAGE Largest amplitude of glycemic excursions, BMI Body Mass Index, HbAlc Glycosylated hemoglobin, GA glycated albumin, hs-CRP high-sensitivity C-reactive protein

Regression analysis

Multivariable linear regression analysis showed that after adjusting for gender, age, and LAGE, SDBG was positively correlated with endotoxin independently (standard partial regression coefficient = 0.255, P = 0.039). The scatter-plot is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Scatter plot of the correlation between endotoxin and SDBG. SDBG: Standard Deviation Of Blood Glucose

Discussion

Previous reports exhibited that patients with T2DM are more susceptible to intestinal mucosal barrier dysfunction [23, 24], however factors remains to be investigated. In this study, T2DM patients with higher daily blood glucose fluctuation tended to have a higher serum endotoxin level, which indicates the function of the intestinal mucosal barrier was possibly compromised.

In this study patients with T2DM and high SDBG were associated with higher serum endotoxin level; meanwhile there was no significant change in serum DAO and D-lactic acid levels. Diamine oxidase (DAO) is an enzyme mainly produced in the small intestine involved in the histamine metabolism [25, 26]. Recent studies showed that a established first-line treatment for patients in T2DM, metformin, inhibits DAO activity [27]. Such inhabitation possibly compensate the increased DAO due to the dysfunction of intestinal mucosal barrier. D-lactate is a bydroxycarboxylic acid produced by bacterial fermentation [28, 29]. Studies revealed that the gut microbiome composition is altered for T2DM patients treated with metformin [30], in which possibly explain the inconsistent result in serum D-lactate and endotoxin level.

Endotoxins, also known as Lipopolysaccharides (LPS), are large molecules found in the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria. The increase in LPS is associated with bacterial translocation due to the impairment of intestinal epithelial cell [31]. The increase in endotoxins of T2DM patients are probably result from the change in gut microbial composition, epithelial cell impairment, responses to inflammatory mediators or secondary action of endotoxins [31–34]. A resent study on mice suggested that fluctuant hyperglycemia had more potential to cause oxidative stress and inflammation, and eventually endothelial dysfunction [35]. In this study, although the amplitude of blood glucose fluctuation of patients are much less than that of mouse model (2.1/2.9 mmol/l vs ~ 15 mmol/l), the SDBG is still an independent factor positively correlated to the serum LPS level. In addition, blood glucose fluctuations are associated with ketoacidosis in patients with DM, and also an independent risk factors for the progression of atherosclerosis [4, 36]. These pevious reports, combined with this study, further indicate the importance of blood glucose stabilization to health.

Previous studies revealed that T2DM patients are more probably associated with higher LPS, in which long-term hyperglycemia in these patients is one of the causes of intestinal mucosal barrier damage [37]. The compromised mucosal barrier could be a potential cause of the large blood glucose fluctuartion. In this study, however, no sign of inflammatory damage of intestinal mucosa was observed as the CRP level of patients are at normal level.

Multivariable linear regression analysis revealed that the amplitude of blood glucose fluctuations was an independent risk factor of increased intestinal permeability. The blood glucose fluctuation compromise the intestinal permeability in several possible ways: (1) Increased blood glucose fluctuations affect the integrity of the intestinal epithelial cells and the contact structure between cells [38]. (2) Abnormal metabolic pathways caused by fluctuations in blood glucose lead to increased inflammatory factors and stimulate intestinal mucosa [38]. (3) Function of liver is compromised due to the flucturation, thereby preventing timely and effective removal of endotoxins.

The positively correlation between intestinal mucosal barrier damage and SDBG indicates that clinicans/ T2DM patients should carefully maintain stable blood glucose level. Subsequent studies should be done to confirm our findings by increasing the sample size. Although DAO, D-lactic acid, and endotoxin can be used as indicators of the intestinal mucosal barrier status, the impairment mechanism of intestinal mucosal barrier remains to be clearly elucidated. Factors such as intestinal microenvironment affected by medication and immunity of patients should be further investigated.

Conclusions

In summary, impairment of the intestinal mucosal barrier function, characterized by impaired intestinal permeability, may occur in patients with T2DM with large SDBG. Clinical attention should be focused on monitoring and controlling blood glucose fluctuations in patients with T2DM.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The work was supported by grants from Shanghai Municipal Jiading District Natural Science Foundation (2015–023), Foundation of the Public Health Bureau of Jiading (2017-KY-06) and New Key Subjects of Jiading District (2017-ZD-03).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- DAO

Diamine oxidase

- DGA

Daily glucose average

- FPG

Fasting Plasma Glucose

- GA

glycated albumin

- HbA1c

Glycosylated hemoglobin

- hs-CRP

High-sensitivity C-reactive protein

- LAGE

Largest amplitude of glycemic excursions

- PBG

Postprandial Blood Glucose

- PPGE

Postprandial glucose excursion

- SDBG

Standard Deviation Of Blood Glucose

- T2DM

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

Authors’ contributions

SL and AL assisted with data analysis, interpretation, and drafting of the manuscript. WF and SJ assisted with study design, statistical analysis and drafting of the manuscript. XH, YX and YD contributed to measuring samples in this study. SJ and XW contributed to data interpretation and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors planned the study design, contributed to the interpretation of the data, and drafted and approved the submitted manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanghai Jiading District Central Hospital, and the acquisition of specimens from all cases was performed with the consent of the patient.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jie Sun, Phone: 00862167073160, Email: jzx117@126.com.

Fei Wang, Phone: 00862167073176, Email: chazwf@163.com.

References

- 1.Yang W, Lu J, Weng J, et al. Prevalence of diabetes among men and women in China. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1090–1101. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malo MS. A high level of intestinal alkaline phosphatase is protective against type 2 diabetes mellitus irrespective of obesity. EBioMedicine. 2015;2:2016–2023. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sato J, Kanazawa A, Ikeda F, et al. Gut dysbiosis and detection of "live gut bacteria" in blood of Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(8):2343–2350. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao H, Li Z, Tian G, et al. Effects of traditional Chinese medicine on rats with type II diabetes induced by high-fat diet and streptozotocin: a urine metabonomic study. Afr Health Sci. 2013;13:673–681. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v13i3.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thaiss CA, Levy M, Grosheva I, et al. Hyperglycemia drives intestinal barrier dysfunction and risk for enteric infection. Science. 2018;359(6382):1376–83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Heron M. Deaths: Leading Causes for 2016. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2018;67(6):1–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayes MT, Foo J, Besic V, et al. Is intestinal gluconeogenesis a key factor in the early changes in glucose homeostasis following gastric bypass? Obes Surg. 2011;21:759–762. doi: 10.1007/s11695-011-0380-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li B1, Zhou X, Wu J, et al. From gut changes to type 2 diabetes remission after gastric bypass surgeries. Front Med. 2013;7:191–200. doi: 10.1007/s11684-013-0258-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koliaki C, Liatis S, le Roux CW, et al. The role of bariatric surgery to treat diabetes: current challenges and perspectives. BMC Endocr Disord. 2017;17(1):50. doi: 10.1186/s12902-017-0202-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scaldaferri F, Pizzoferrato M, Gerardi V, et al. The gut barrier: new acquisitions and therapeutic approaches. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46(Suppl):S12–S17. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31826ae849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang X, Gao XC, Liu J, et al. Effect of EPEC endotoxin and bifidobacteria on intestinal barrier function through modulation of toll-like receptor 2 and toll-like receptor 4 expression in intestinal epithelial cell-18. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(26):4744–4751. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i26.4744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Attas OS, Al-Daghri NM, Al-Rubeaan K, et al. Changes in endotoxin levels in T2DM subjects on anti-diabetic therapies. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2009;15:8–20. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-8-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Creely SJ, McTernan PG, Kusminski CM, et al. Lipopolysaccharide activates an innate immune system response in human adipose tissue in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292(3):E740–E747. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00302.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lozupone CA, Stombaugh JI, Gordon JI, et al. Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature. 2012;489:220–230. doi: 10.1038/nature11550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Genton L, Cani PD, Schrenzel J. Alterations of gut barrier and gut microbiota in food restriction, food deprivation and protein-energy wasting. Clinl Nutr. 2015;34:341–349. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cyphert TJ, Morris RT, House LM et al. NF-κB-dependent airway inflammation triggers systemic insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2015;309:R1144–R1152. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00442.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaĭdashev IP. NF-kB activation as a molecular basis of pathological process by metabolic syndrome. Fiziol Zh. 2012;58:93–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferdaoussi M, Abdelli S, Yang JY, et al. Exendin-4 protects beta-cells from interleukin-1 beta-induced apoptosis by interfering with the c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase pathway. Diabetes. 2008;57:1205–1215. doi: 10.2337/db07-1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu J, Liu Z, Zhan W, et al. Recombinant TsP53 modulates intestinal epithelial barrier integrity via upregulation of ZO-1 in LPS-induced septic mice. Mol Med Rep. 2018;17(1):1212–1218. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.7946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao X, Miao R, Tao Y, et al. Effect of montmorillonite powder on intestinal mucosal barrier in children with abdominal Henoch-Schonlein purpura: a randomized controlled study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97(39):e12577. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000012577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garber AJ, Abrahamson MJ, Barzilay JI, et al. Consensus statement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of endocrinology on the comprehensive type 2 diabetes management algorithm-2018 executive summary. Endocr Pract. 2018;24:91–120. doi: 10.4158/CS-2017-0153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes--2014. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(Suppl 1):S14–80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Zhong H, Yuan Y, Xie W, et al. Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Is Associated with More Serious Small Intestinal Mucosal Injuries. PLoS ONE. 11(9):e0162354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Horton F, Wright J, Smith L, et al. Short Report: Pathophysiology Increased intestinal permeability to oral chromium (51Cr)-EDTA in human Type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2014;31:559–563. doi: 10.1111/dme.12360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao L, Luo L, Jia W, et al. Serum diamine oxidase as a hemorrhagic shock biomarker in a rabbit model. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e102285. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bragg LE, Thompson JS, West WW. Intestinal diamine oxidase levels reflect ischemic injury. J Surg Res. 1991;50(3):228–233. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(91)90183-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yee SW, Lin L, Merski M, et al. Prediction and validation of enzyme and transporter off-targets for metformin. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2015;42(5):463–475. doi: 10.1007/s10928-015-9436-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Demircan M, Cetin S, Uguralp S, et al. Plasma D-lactic acid level: a useful marker to distinguish perforated from acute simple appendicitis. Asian J Surg. 2004;27(4):303–305. doi: 10.1016/S1015-9584(09)60056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun XQ, Fu XB, Zhang R, et al. Relationship between plasma D(−)-lactate and intestinal damage after severe injuries in rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7(4):555–558. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i4.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCreight LJ, Bailey CJ, Pearson ER. Metformin and the gastrointestinal tract. Diabetologia. 2016;59(3):426–435. doi: 10.1007/s00125-015-3844-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cavaillon JM. Exotoxins and endotoxins: inducers of inflammatory cytokines. Toxicon. 2018;149:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2017.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu X, Ma C, Han L, et al. Molecular characterisation of the faecal microbiota in patients with type II diabetes. Curr Microbiol. 2010;61:69–78. doi: 10.1007/s00284-010-9582-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cani PD, Amar J, Iglesias MA, et al. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2007;56:1761–1772. doi: 10.2337/db06-1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Al-Obaide MAI, Singh R, Datta P, et al. Gut Microbiota-Dependent Trimethylamine-N-oxide and Serum Biomarkers in Patients with T2DM and Advanced CKD. J Clin Med. 2017;6(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Wu N, Shen H, Liu H, et al. Acute blood glucose fluctuation enhances rat aorta endothelial cell apoptosis, oxidative stress and pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in vivo. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2016;15:109. doi: 10.1186/s12933-016-0427-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martín-Timón I, Sevillano-Collantes C, Segura-Galindo A, et al. Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease: have all risk factors the same strength? World J Diabetes. 2014;5:444–470. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v5.i4.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jayashree B, Bibin YS, Prabhu D, et al. Increased circulatory levels of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and zonulin signify novel biomarkers of proinflammation in patients with type 2 diabetes. Mol Cell Biochem. 2014;388(1–2):203–210. doi: 10.1007/s11010-013-1911-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oliveira RB, Canuto LP, Collares-Buzato CB. Intestinal luminal content from high-fat-fed prediabetic mice changes epithelial barrier function in vitro. Life Sci. 2019;216:10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2018.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.