Abstract

Discrimination is a pervasive stressor among African-American adults. Social support is an important protective factor for psychological distress, especially among minority populations. Although a number of studies have examined social support in relation to discrimination, little research has examined how social support may serve as an important protective factor against both physical and psychological symptoms related to overall psychological distress within this group. The current study examined social support as a moderator of the relationship between discrimination and overall psychological distress as measured by the Brief Symptom Inventory among a community sample of 122 African-American church-going adults. Results indicated that social support buffered the associations of discrimination and overall psychological distress (p<.0001) in expected directions. Findings highlight the importance of cultivating strong social relationships to attenuate the effects of this social determinant on mental health disparities among this group.

Keywords: Psychological distress, social support, discrimination, African Americans, resilience

1. Introduction

In a 2017 nationally representative probability survey of over 800 African-American adults, an overwhelming majority (92%) perceived they had been discriminated against both at an institutional and a personal level due to their race (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation [RWJF], 2017). Thus, racial discrimination, which has been defined as unfair treatment as a result of an individual’s race/ethnicity (Ong, Fuller-Rowell, & Burrow, 2009), is a common stressor experienced by many African Americans. In fact, African Americans report facing the most discrimination of any minority population (Albert et al., 2008; Bhui et al., 2005; Kessler, Mickelson, & Williams, 1999), and a majority of African-American adults indicate they have encountered some form of day-to-day discrimination on a regular basis (e.g., “often” or an average of 3.5 discriminatory events across the two week study period; Kessler et al., 1999; Ong et al., 2009).

African-American adults experience discrimination in a multitude of domains including but not limited to: educational settings (Prelow, Mosher, & Bowman, 2006), in the workplace (Deitch, Barsky, Butz, Chan, & et al., 2003), while searching for housing (Galster & Carr, 1991), in interactions with law enforcement (Brunson, 2007; RWJF, 2017), and in medical settings (Burgess, Ding, Hargreaves, Ryn, & Phelan, 2008; Smedley, Stith, & Nelson, 2003). Although African-American men are more likely to report more experiences of discrimination compared to women (Albert et al., 2008; Sims et al., 2012), African-American women may be more likely to rate experiences of discrimination as being more stressful than men (Sims et al., 2012). Younger African Americans are likely to perceive the most discrimination, with older groups perceiving less discrimination (Albert et al., 2008; Kessler et al., 1999; D. C. Watkins, Hudson, Howard Caldwell, Siefert, & Jackson, 2010). Furthermore, incidences of discrimination against African Americans occur at all socioeconomic status levels (RWJF, 2017). In fact, research has demonstrated that African Americans who are higher income earners report experiencing the most discrimination (Albert et al., 2008; Borrell et al., 2007).

Perhaps as a consequence of exposure to chronic race-related stressors such as discrimination, African Americans face more negative physical and mental health outcomes than individuals of other races. Rates of hypertension, diabetes, and stroke risk are disproportionately high among African-American adults (Benjamin et al., 2017; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2015). Moreover, despite significant advances in medical technology, African Americans have a substantially higher risk of early mortality relative to Whites (Cunningham et al., 2017; Murphy, Xu, Kochanek, Curtin, & Arias, 2017). Perceived racism/discrimination has been linked to increased psychological distress (Pieterse, Todd, Neville, & Carter, 2012; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2016), greater depressive symptoms (Brondolo et al., 2008; Cuevas et al., 2013; Schulz et al., 2006) and lower life satisfaction (Ayalon & Gum, 2011) among African Americans. In general, perceived discrimination has been associated with negative mental health outcomes more consistently than physical health outcomes (Chae, Lincoln, & Jackson, 2011; Davis, Liu, Quarells, & Din-Dzietharn, 2005; Nancy Krieger, Kosheleva, Waterman, Chen, & Koenen, 2011; Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009; Williams, Neighbors, & Jackson, 2003). Thus, it is important to examine possible psychosocial factors that may help to mitigate mental health effects stemming from discrimination directed toward African-American adults.

Extant literature has suggested that an important psychosocial factor to investigate in relation to discriminatory effects on mental health is social support. Social support theory hypothesizes that the supportive actions of others (e.g., behavioral assistance, advice provision), or the perceived availability of support helps to alleviate negative health effects due to stress (Lakey & Cohen, 2000). Furthermore, in their meta-analytic review of perceived discrimination on health, Pascoe and Smart Richman (2009) indicated that social support may function as a buffer between discrimination and psychological distress “by enabling an individual to challenge the validity of discriminatory events and reduce negative feelings about the self, thereby reducing the chance that discriminatory experiences will exert an enduring impact on mental health outcomes” (p. 533). Research has found that many racial/ethnic minorities in the U.S. (e.g., Hispanics and Asian Americans), particularly those from collectivistic cultures, may utilize social support to lessen psychological distress caused by frequent discrimination (Finch & Vega, 2003; Mossakowski & Zhang, 2014; Mulvaney-Day, Alegria, & Sribney, 2007), since collectivistic cultures value close relationships with family, friends, and community more so than individualistic cultures (Markus & Kitayama, 1999, 2001). As African-American culture has been deemed to be collectivistic in nature (Carson, 2009; Coon & Kemmelmeier, 2001; Obasi, Flores, & James-Myers, 2009; Obasi & Leong, 2010), it stands to reason that African Americans may depend on social support to mollify the psychological effects caused by discrimination.

To our knowledge, only a handful of studies have examined social support in relation to discrimination and mental health among African-American populations (Ajrouch, Reisine, Lim, Sohn, & Ismail, 2010; Odafe, Salami, & Walker, 2017; Prelow et al., 2006). The extant research in the area has primarily focused on lower income African-American samples such as urban African-American women living in underprivileged neighborhoods (Ajrouch et al., 2010) and African-American college students (Prelow et al., 2006). However, as previously indicated, income may play a role in perceived discrimination such that African Americans in higher income brackets perceive greater levels of discrimination (Albert et al., 2008; Borrell et al., 2007). Additionally, although the literature has yet to explore the buffering effects of social support in relation to discrimination and psychological distress among religious African Americans, a descriptive study found that African Americans give and receive more social support within a church setting than outside a church setting relative to other racial groups (Krause, 2016). Moreover, African Americans overall are more religious than those of other race/ethnicities, with over half of this population attending services weekly (Pew Research Center, 2009). Therefore, it may be important to examine how social support functions in alleviating race-related psychological effects of discrimination among a church-going African American population.

The current research seeks to bridge the above gaps in the literature by investigating social support as a critical buffer in mitigating the negative mental health outcomes due to race-based discrimination by examining the associations between social support, discrimination, and psychological distress among a church-going, middle income sample of African-American adults. Based on the prior literature, we expected significant main effects for discrimination and social support in predicting psychological distress such that experiencing discrimination would be positively associated with psychological distress (H1; Albert et al., 2008; Kessler et al., 1999; Sims et al., 2012) whereas social support would be negatively associated with psychological distress (H2; Ajrouch et al., 2010; Odafe et al., 2017; Prelow et al., 2006). We also expected that social support would moderate the association between discrimination and psychological distress, such that those who perceived they had higher levels of social support would experience much less psychological distress, even at higher levels of discrimination, than those lacking in social support (H3).

2. Method

2.1. Participants and procedures

Participants consisted of a convenience sample of African American adults recruited from a large church (>10,000 members) in Houston, Texas. Several research studies were previously conducted in cooperation with church leadership at this site (Advani et al., 2014; Hernandez, Reitzel, Wetter, & McNeill, 2014; Mama et al., 2016; Maness, Reitzel, Watkins, & McNeill, 2016; Nguyen et al., 2017; Reitzel et al., 2016; Reitzel et al., 2014; Watkins, Reitzel, Wetter, & McNeill, 2015). Recruitment was accomplished via email solicitation of previous research participants and through word of mouth. The email described a study was being conducted on stress and health among African-American adults and provided contact information for how to contact the investigator’s lab in order to participate in the study. Interested individuals who called the lab were prescreened for eligibility by phone. Eligibility criteria included: 1) adults ages 18 years and over; 2) self-identified African-American race; 3) willingness to provide valid contact information; and 4) willingness to comply with the described study protocol, which included two in-person visits to the church (of which only the first study visit is relevant to the current study). Interested and eligible individuals were then scheduled for a date and time to be screened in-person, provide informed consent for participation, enroll in the study, and complete the study survey. All of these procedures took place in a dedicated study room at the church. Based on funding, the study was limited to 124 participants.

Participants completed the study survey on a laptop computer and the questions were read aloud through headphones. Participants were compensated up to $100 in department store gift cards for the completion of all study procedures. Study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the primary (University of Houston) and collaborating (University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center) institutions and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Participant characteristics

Self-reported sociodemographic characteristics for this study included sex, age, and income. Perceived stress was self-reported using a 4-item measure that included items such as: “In the last week, how often have you felt difficulties were piling up so high that you could not overcome them?” (Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983). Physical health was measured via a single, self-rated health item (“In general, would you say that your health is… ?”) where 1=fair or poor and 2=excellent, good, or very good (Ware & Gandek, 1998).

2.2.2. Discrimination

The Everyday Discrimination Scale (Williams, Yan, Jackson, & Anderson, 1997) was used to assess perceived discrimination. This 9-item measure queries: “In your day-to-day life how often have any of the following things happened to you based on your race/ethnicity or skin color?” with items including “You are treated with less respect than other people,” “People act as if they think you are not smart,” and “You are threatened or harassed.” Options for each item were as follows: 0=almost every day, 1=at least once a week, 2=a few times a month, 3=a few times a year, 4=less than once a year, and 5=never. Previous validation studies have indicated the scale reliably yields a single principal factor (Clark, Coleman, & Novak, 2004; Kessler et al., 1999; Krieger, Smith, Naishadham, Hartman, & Barbeau, 2005). Responses were reverse scored and summed with a potential range of 0 to 40, where higher scores were indicative of greater perceived discrimination. Cronbach’s alpha in this sample was 0.90.

2.2.3. Psychological distress

The Global Severity Index (GSI) from the 53-item Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI; Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1983) was used in the current study as an indicator of psychological distress. Respondents ranked each feeling item (e.g. “your feelings are easily hurt”) and item responses range from 0=not at all, 1 = a little bit, 2 = moderately, 3 = quite a bit, and 4 = extremely. Higher scores were associated with greater psychological distress. Responses were summed (no missing data), with a potential range of 0 to 212. Cronbach’s alpha for the BSI GSI in this sample was 0.98.

2.2.4. Social support

The 12-item International Support Evaluation List (ISEL; Cohen & Hoberman, 1983) was used to assess social support. The ISEL measures the perceived availability of social support across a variety of situations including appraisal, belonging, and tangible support. Although the ISEL can used to assess the these individual dimensions of social support, validation studies have indicated that it is also possible to sum the items to create a global, first-order cumulative social support score, which was used herein (ISEL total; e.g., Cohen, McGowan, Fooskas, & Rose, 1984; Merz et al., 2014). Six negatively-worded items were reverse scored such as, “I feel that there is no one I can share my most private worries and fears with,” “I don’t often get invited to do things with others,” and “If a family crisis arose, it would be difficult to find someone who could give me good advice about how to handle it.” Response options for each item were as follows: 1=definitely false, 2=probably false, 3=probably true, and 4=definitely true. Total ISEL score could range from 12 to 48, with higher scores indicative of greater social support. The Cronbach’s alpha for the ISEL total in this sample was 0.88.

2.3. Statistical analyses

The descriptive statistics of participant characteristics were examined and intercorrelations of study variables were assessed. We controlled for sex, due to the previous findings indicating that African-American women are more likely to rate experiences of discrimination as being more stressful than men (Sims et al., 2012). We also controlled for age, because of research suggesting that African Americans may perceive less discrimination as they grow older (Albert et al., 2008; Kessler et al., 1999; Watkins et al., 2010).Self-rated health and perceived stress were included as covariates based on prior literature linking discrimination to these constructs (e.g., Cuevas et al., 2013). To examine the independent contributions of each set of factors on psychological distress, linear regressions were built in a hierarchical fashion consisting of three steps where independent variables were sequentially added and retained: 1) participant characteristics of age, sex, perceived stress, and self-rated health (Step 1); 2) the addition of discrimination and social support into the model (Step 2); and 3) the previous predictors and the interaction term of discrimination and social support (Step 3). After each step, the increase in total explained outcome variance (ΔR2adj) was computed. This approach highlights the unique contribution of the predictors entered in at each step of the model by examining the change in the variance of the outcome variable after the addition of new predictors. Continuous variables were mean-centered, and the distribution of residuals of the outcome variable were examined to ensure their normality.

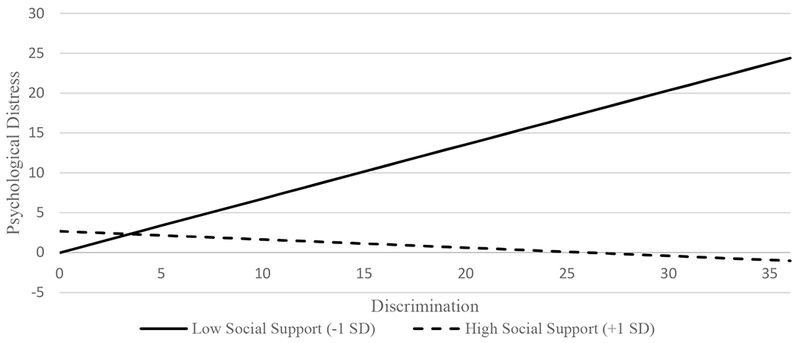

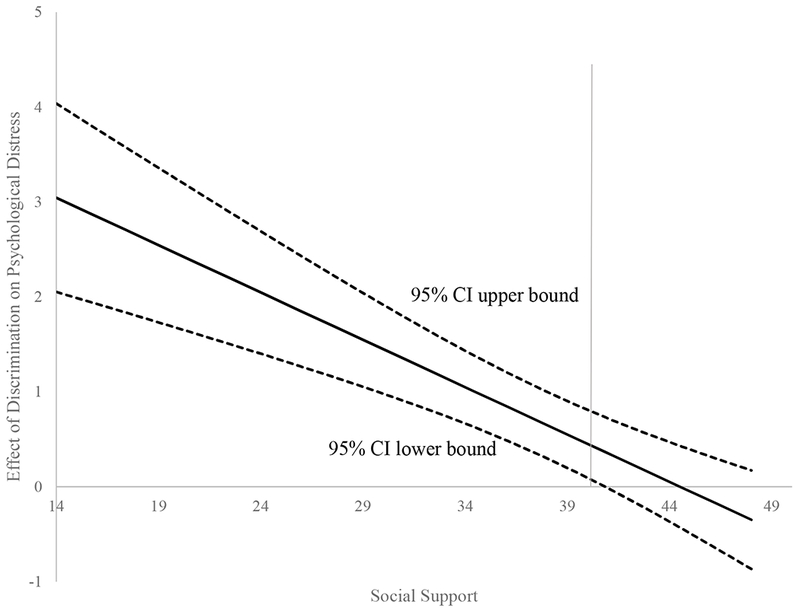

The interactive effect was plotted using a pick-a-point approach. The values of one standard deviation above and below the mean of the moderator were calculated to represent higher and lower levels of social support. The parameter estimates yielded from the hierarchical linear regression analyses were used to obtain the predicted values of psychological distress. In addition, the Johnson-Neyman technique (Johnson & Neyman, 1936) was used to probe the significant interaction within the observed range of values of the moderator. Unlike the common pick-a-point approach which selects representative values (e.g., low, medium, and high) of the moderator variables, the Johnson-Neyman method works backwards to find regions of significance, and derives a point estimate along the continuum of the moderator (social support) at which the effect of independent variable transitions from being statistically significant from zero to non-significant (Bauer & Curran, 2005; Hayes & Matthes, 2009). The significance level was set atp < 0.05. All the analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, 2013).

3. Results

3.1. Participant characteristics

Table 1 displays the participant characteristics and the correlations between the primary study variables. Females comprised 79% of the 124 African-American participants in the sample. The average age was 49.02 ± 11.47 years (range: 19-75). With regard to income, 58.1% of the sample reported > $42,000 annually (not in Table 1). The total score for everyday discrimination was 9.78 ± 7.62 out of a possible range of 0 to 40. The average psychological distress reported by this sample was 6.94 ±19.07 with an actual range of scores from 0 to 133 (out of the possible range of 0 to 212). Average endorsed social support was on the higher end of the spectrum (41.12 ±6.67) out of a possible range of 12 to 48. Psychological distress was significantly negatively correlated with age (r = −0.22) and social support (r = −0.43), but significantly positively correlated with discrimination (r = 0.46) and perceived stress (r = 0.58). Discrimination was significantly negatively correlated with social support (r = −0.35).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics and correlations between study variables (N=124).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | M (or n) | SD (or %) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sex (% female) | 1 | −0.12 | 0.15 | −0.05 | −0.12 | 0.13 | 0.09 | (98) | (79.03) |

| 2. Age | 1 | −0.22* | 0.05 | −0.17 | 0.04 | −0.22* | 49.02 | 11.47 | |

| 3. Perceived Stress Scale | 1 | −0.27** | 0.35*** | −0.47*** | 0.58*** | 4.79 | 3.08 | ||

| 4. Self-rated Health (% excellent/very good/good health) | 1 | −0.01 | 0.08 | −0.13 | (95) | (76.61) | |||

| 5. Every Day Discrimination | 1 | −0.35*** | 0 46*** | 9.78 | 7.62 | ||||

| 6. Social Support | 1 | −0.43*** | 41.12 | 6.67 | |||||

| 7. Psychological Distress | 1 | 6.94 | 19.07 |

Note.

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001.

Discrimination was measured with Every Day Discrimination, social support was measured with the total score on the International Support Evaluation List, perceived stress was measured with the 4-item Perceived Stress Scale, and Psychological Distress was measured with the Global Severity Index of the Brief Symptom Inventory.

3.2. Main analyses

Participants whose psychological distress score was 3 standard deviations above or below the mean were excluded from the main analyses resulting in an analytic sample size of 122. Sex, age, perceived stress, and self-rated health were simultaneously entered in the equation for the hierarchical multiple linear regression model at Step 1, but only perceived stress emerged as a significant positive predictor (B= 1.81, p < 0.001) of psychological distress (R2adj = 0.22, F(4, 117) = 9.3, p < 0.0001). Step 2 of the regression model included the control variables from Step 1 (age, sex, perceived stress, and self-rated health) along with discrimination and social support and yielded an R2adj = 0.33 (F(6, 115) =10.9, p < 0.0001). The results of the main effects for discrimination (H1) and social support (H2) were supported. As expected, discrimination was significantly positively associated with psychological distress (B = 0.37, p = 0.0025) whereas social support was significantly negatively associated with psychological distress (B = −0.397, p =0.0049). Moreover, the variance accounted for in terms of psychological distress increased significantly (Δ R2adj = 0.114, F(2, 115) = 10.94, p < 0.0001). In Step 3, the interaction between discrimination and social support was entered as an additional predictor in the complete model which yielded an R2adj of 0.47 (F(7, 114) = 16.05, p < 0.0001). As anticipated, the interaction term of discrimination and social support was significant (B = −0.07, p < 0.001) lending support to H3. Furthermore, the change in R2adj, Δ R2adj = 0.14, was statistically significant (F(1, 114) = 30.28, p < 0.001). See Table 2. The distribution of the residuals was acceptable and was not highly skewed.

Table 2.

Hierarchical multiple regression model testing the interaction of discrimination and social support on psychological distress (n=122).

| B | p | R2adj | ΔR2adj | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Sex | −0.327 | 0.876 | 0.215 | |

| Age | −0.039 | 0.610 | |||

| Perceived Stress | 1.807 | 0.610 | |||

| Self-rated Health | 0.211 | 0.920 | |||

| Step 2 | Discrimination | 0.370 | 0.003 | 0.329 | 0.114*** |

| Social Support | −0.397 | 0.005 | |||

| Step 3 | Discrimination*Social Support | −0.066 | <.0001 | 0.465 | 0.136*** |

Note.

p<0.001.

Discrimination was measured with Every Day Discrimination, social support was measured with the total score on the International Support Evaluation List, perceived stress was measured with the 4-item Perceived Stress Scale, and Psychological Distress was measured with the Global Severity Index of the Brief Symptom Inventory.

Figure 1 demonstrates the interaction between social support and discrimination in predicting psychological distress. The interaction is visually evident and the simple slopes analyses showed a significant relationship between discrimination and psychological distress for lower levels of social support (B = 0.64, p < 0.001) but not for higher levels of social support (B = −0.22, p = 0.16). Figure 2 provides the results of the Johnson-Neyman technique with a plot illustrating a 95% Confidence Interval of the conditional effect of discrimination on psychological distress for observed sample values of social support. The significant transition point for social support (not mean centered) was 40.86. The confidence intervals for the simple slopes did not include zero for values of social support below 40.86, indicating the effect of discrimination on psychological distress was significantly different from zero for values of social support below this transition point (34.68% of the sample).

Figure 1.

Simple slopes of the model relating psychological distress to discrimination, social support, and their interaction.

Figure 2.

Plot illustrating 95% Confidence Interval of the Conditional Effect of Discrimination on Psychological Distress for Observed Sample Values of Social Support.

4. Discussion

The current research contributes to the growing body of literature by providing evidence that social support may serve an important protective function against both physical and psychological symptoms related to overall psychological distress as associated with discrimination among a church-going, middle income sample of African-American adults. Discrimination is a common and potentially regular stressor experienced by African Americans (Davis et al., 2005; Krieger et al., 2011) an is associated with poorer physical (Krieger & Sidney, 1996; Mays, Cochran, & Barnes, 2007; Smelser, Wilson, & Mitchell, 2001; Taylor, Repetti, & Seeman, 1997) and psychological health outcomes (Pieterse et al., 2012; USDHHS, 2016). For these reasons, the level of social support that an individual perceives is an important indicator of their potential resiliency in the face of discrimination experiences that continue to unjustly plague African-American adults. Although not directly examined in this work, results may also suggest the potential benefit of seeking increased social support when coping with discriminatory events as a method of mitigating psychological distress. Future research should examine this possibility within prospective research designs.

In the present sample, consistent with extent literature, we found a significant, positive main effect for discrimination (B= 0.37, p <.01) in predicting psychological distress such that participants who experienced more discrimination reported more psychological distress (Chae et al., 2011; Davis et al., 2005; Krieger et al., 2011; Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009; Williams et al., 2003). Moreover, we found a significant, negative main effect for social support (B=−0.397, p <.01) indicating that participants who received social support were more likely to report lower levels of psychological distress, which is also consistent with previous research (Ajrouch et al., 2010; Odafe et al., 2017; Prelow et al., 2006). Finally, the addition of the interaction of social support with discrimination significantly increased the variance in psychological distress explained and accounted for by about 14%. Thus, results provide strong evidence of the moderating effect of social support on the relationship between discrimination and overall psychological distress among this sample, which was unique in the extant literature based on its composition of largely middle income and church-going adults. Individuals higher in social support reported lower psychological distress, regardless of their levels of discrimination; conversely, individuals with lower social support who reported higher levels of perceived discrimination appeared to experience much more psychological distress. This finding is important as psychological distress is associated with numerous negative outcomes, including cardiovascular events (Hamer, Molloy, & Stamatakis, 2008), decreased help-seeking behavior (Obasi & Leong, 2009), and premature mortality (Lazzarino, Hamer, Stamatakis, & Steptoe, 2013) among African-American adults.

The implications of the current results include that clinicians providing interventions for African-American individuals struggling with psychological distress should assess the role of both discrimination as well as perceived social support. When lower perceived social support is an issue, appropriate interventions or recommendations should be made to increase such support, which may even include a targeted focus on strategies to enhance the most impactful or potentially deficient support (e.g., tangible aid, emotional availability). Although to our knowledge social support interventions have yet to target African-American populations (healthy or otherwise), social support has been found to have a palliative effect among African American diabetics (Ford, Tilley, & McDonald, 1998a, 1998b) and African Americans with cancer (Hamilton & Sandelowski, 2004; Thompson et al., 2017).

There are many aspects of this sample that should be considered in interpreting these results. First, the current sample comprised African-American adults of relatively high income (e.g., 58.1% of the sample reported an annual household income of $42,001 and above with 16.1% indicating a household income of $84,000 or more). Given that previous literature suggests that discrimination might be greater among African Americans earning higher incomes (Albert et al., 2008; Borrell et al., 2007), this was an important sample within which to examine the moderating role of social support on the associations of discrimination and distress. Post-hoc analyses controlling for variances in income within our sample, however, yielded virtually identical coefficients and significance levels as those presented in our results. Second, a minority of participants reported experiencing discrimination at least a few times a month, if not every day. Conversely, a majority of participants reported experiencing discrimination a few times a year or less than once a year. This is similar to extant literature indicating that African Americans endorse experiencing discrimination a few times a year (Ajrouch et al., 2010; Kendzor et al., 2014; Lewis, Aiello, Leurgans, Kelly, & Barnes, 2010; Tomfohr, Cooper, Mills, Nelesen, & Dimsdale, 2010), but somewhat unexpected given that higher income earners may experience more frequent experiences with discrimination (Albert et al., 2008; Borrell et al., 2007).

The fact that the current population was church-going may help to explain the lower reports of perceived discrimination, as church-going populations who frequently practice their religious beliefs tend to report greater meaning in life (Berthold & Ruch, 2014) as well as lower levels of depression (Huang, Hsu, & Chen, 2011) and anxiety (Ellison, Burdette, & Hill, 2009). It is also notable that participants reported, on average, higher levels of social support, and which may possibly be reflective of church affiliation since previous literature has found that church goers often derive their levels of social support from within their congregation (Krause, 2016). Although the current study did not assess this directly, it may be possible that deferring to a higher power may allow African Americans to cognitively reappraise race-related stressors like discrimination, thereby lessening associated psychological distress. In addition, it might be possible that being a part of an organized religion strengthens relationships between congregation members; thus, church-going African Americans may feel more supported and cognitively reappraise discriminatory events through their social support lens. As African Americans are more likely to self-identify as religious, as compared to other populations (Campbell et al., 2007), future research should be conducted to better elucidate the role in which religiosity or religious affiliation plays on the relationship between discrimination and psychological distress among this group.

Several limitations should be considered in light of the current study’s strengths. One possible limitation is the use of an adult sample from a single church in Texas. This convenience sample may limit generalizability of the results to African-American individuals outside of the region, those who are non-church-going, or those ascribing to another religion or parish. However, given the strong association between social support and church attendance (Giger, Appel, Davidhizar, & Davis, 2008; Krause, 2016), insight into the role that social support plays in the relationship between discrimination and psychological distress among this group provides a unique contribution to extant research. Another limitation of the current work stems from its cross-sectional nature, which limits the ability to draw definitive conclusions regarding the role of social support as a buffer of the relationship between discrimination and psychological distress over time, the role of the church in social support, etc. Future studies should explore these relationships longitudinally and examine interactions of age, discrimination, and social support over time as it relates to psychological distress. Finally, the sample was largely middle-aged and predominantly women. While age and sex were controlled for in analyses, social support manifests differently for varying ages and sexes (Eagly, 1987; Scholz, Kliegel, Luszczynska, & Knoll, 2012). Further examination of this topic might compare differences between sexes or various age ranges to learn more about the role that each factor plays in the relationship between social support, discrimination, and psychological distress.

5. Conclusion

The current research contributes to understanding of the potential role of social support in psychological well-being and resiliency among a population at high risk of experiencing racially-motivated discriminatory events. Potentially as a result of this and other stressors, approximately 20% of African-American adults report serious psychological distress levels more than Whites adults (USDHHS, 2016). However, despite the fact that African Americans may experience more psychological distress than other racial groups, only about 25% of African Americans seek treatment for mental health issues as compared to 40% of Whites (National Alliance on Mental Illness, 2015). Community and family stigma further contribute to the underutilization of mental healthcare services among African Americans. For instance, in a qualitative study of 34 African Americans, 76% indicated that the cultural stigma surrounding mental illness prevented them from seeking mental healthcare. Moreover, 35% of respondents associated diagnoses with even mild mental health issues (e.g., minor depression) with “being crazy”, and 24% believed that seeking mental healthcare would reflect poorly on their family’s ability to handle problems internally (Alvidrez, Snowden, & Kaiser, 2008). Thus, within the context of cultural mores against seeking support through means of formal treatment, recognition of the potential benefits of support garnered through church affiliation is potentially significant.

Based on the current research, clinicians, mental health care professionals, and/or community groups should consider promoting strong social relationships and ties among African-American adults as a means to cope with racially-based discrimination events. This would be beneficial in that it provides a culturally compatible, and potentially low-cost opportunity to attenuate the effects of discrimination on mental health and promote overall wellness among this group. Prior research among African-American adults has shown social support is associated with increased optimism (Seawell, Cutrona, & Russell, 2014), fewer depressive symptoms over one’s lifetime (Lincoln, Chatters, & Taylor, 2005), and increased resiliency in times of stress (Brown, 2008). By fostering social support within African-American communities and community settings such as church congregations, the negative impacts of discrimination can be attenuated; therefore, promoting social support may help to reduce the severity of the mental health disparities experienced by this group.

Highlights:

Everyday discrimination was positively associated with psychological distress.

Social support buffered the impact of discrimination on psychological distress.

Social support may provide resilience against mental health disparities.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the research staff at the University of Houston who assisted with implementation of the project including Alison Shellman, Hannah LeBlanc, Sarah Childress, Hui-Ling “Michelle” Chang, Alexis Moisiuc, Daniel Kish, and Erin “Charli” Washington. Finally, we especially want to thank the church leadership (who approved the study and provided a devoted room for data collection) and the participants (whose contributions made this study possible).

Funding Sources

This project was supported by institutional funding from the University of Houston and the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (to LR Reitzel) and the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health through The University of Texas MD Anderson’s Cancer Center Support Grant (CA016672). Recruitment was achieved with the assistance of Project CHURCH (Creating a Higher Understanding of cancer Research and Community Health) staff who were partially supported by the Duncan Family Institute through the Center for Community-Engaged Translational Research. Manuscript authorship was further supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse through R01 DA034739 (to EM Obasi), the National Cancer Institute through P20 CA221697 (to LR Reitzel) and P20 CA221696 (to LH McNeill), and the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism through K99 AA025394 (to M-LN Steers). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the project supporters.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Competing Financial Interests

Authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Advani PS, Reitzel LR, Nguyen NT, Fisher FD, Savoy EJ, Cuevas AG, … McNeill LH (2014). Financial strain and cancer risk behaviors among African Americans. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention, 23(6), 967–975. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajrouch KJ, Reisine S, Lim S, Sohn W, & Ismail A (2010). Perceived everyday discrimination and psychological distress: Does social support matter? Ethnicity &Health, 15(4), 417–434. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2010.484050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert MA, Ravenell J, Glynn RJ, Khera A, Halevy N, & de Lemos JA (2008). Cardiovascular risk indicators and perceived race/ethnic discrimination in the Dallas Heart Study. American Heart Journal, 156(6), 1103–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.07.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvidrez JP, Snowden LRP, & Kaiser DML (2008). The experience of stigma among Black mental health consumers. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 19(3), 874–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayalon L, & Gum AM (2011). The relationships between major lifetime discrimination, everyday discrimination, and mental health in three racial and ethnic groups of older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 15(5), 587–594. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2010.543664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer DJ, & Curran PJ (2005). Probing Interactions in Fixed and Multilevel Regression: Inferential and Graphical Techniques. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 40(3), 373–400. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr4003_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Das SR, Deo R, … Muntner P (2017). Heart disease and stroke statistics-2017 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Journal of the American Heart Association, 735(10), 146–603. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berthold A, & Ruch W (2014). Satisfaction with life and character strengths of non-religious and religious people: it’s practicing one’s religion that makes the difference. Frontiers in Psychology, 5(876). doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhui K, Stansfeld S, McKenzie K, Karlsen S, Nazroo J, & Welch S (2005). Racial/Ethnic discrimination and common mental disorders among workers: Findings from the EMPIRIC study of ethnic minority groups in the United Kingdom. American Journal of Public Health, 95(3), 496–501. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.033274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrell LN, Jacobs JDR, Williams DR, Pletcher MJ, Houston TK, & Kiefe CI (2007). Self-reported racial discrimination and substance use in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Adults study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 766(9), 1068–1079. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brondolo E, Brady N, Thompson S, Tobin JN, Cassells A, Sweeney M, … Contrada RJ (2008). Perceived racism and negative affect: Analyses of trait and state measures of affect in a community sample. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 27(2), 150–173. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2008.27.2.150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DL (2008). African American resiliency: Examining racial socialization and social support as protective factors. Journal of Black Psychology, 34(1), 32–48. doi: 10.1177/0095798407310538 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brunson RK (2007). “Police don’t like Black people”: African-American young men’s accumulated police experiences. Criminology & Public Policy, 6(1), 71–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9133.2007.00423.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess DJP, Ding Y, Hargreaves M, van Ryn M, & Phelan S(2008). The association between perceived discrimination and underutilization of needed medical and mental health care in a multi-ethnic community sample. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 19(3), 894–911. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell MK, Hudson MA, Resnicow K, Blakeney N, Paxton A, & Baskin M (2007). Church-based health promotion interventions: Evidence and lessons learned. Annual Review of Public Health, 28(1), 213–234. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson LR (2009). “I am because we are:” Collectivism as a foundational characteristic of African American college student identity and academic achievement. Social Psychology of Education, 12(3), 327–344. doi: 10.1007/s11218-009-9090-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015). Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Data, from https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/2015/summary_matrix_15_version12.html Accessed on 10/18/18.

- Chae DH, Lincoln KD, & Jackson JS (2011). Discrimination, attribution, and racial group identification: Implications for psychological distress among Black Americans in the National Survey of American Life (2001–2003). American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 81(4), 498–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2011.01122.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Coleman AP, & Novak JD (2004). Brief report: Initial psychometric properties of the everyday discrimination scale in black adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 27(3), 363–368. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen LH, McGowan J, Fooskas S, & Rose S (1984). Positive life events and social support and the relationship between life stress and psychological disorder. American Journal of Community Psychology, 12(5), 567–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, & Hoberman HM (1983). Positive events and social supports as buffers of life change stress. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 13(2), 99–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1983.tb02325.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, & Mermelstein R (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396. doi: 10.2307/2136404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coon HM, & Kemmelmeier M (2001). Cultural orientations in the United States: (Re)Examining differences among ethnic groups. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32(3), 348–364. doi: 10.1177/0022022101032003006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas AG, Reitzel LR, Cao Y, Nguyen N, Wetter DW, Adams CE, … McNeill LH (2013). Mediators of discrimination and self-rated health among African Americans. American Journal of Health Behavior, 37(6), 745–754. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.37.6.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham TJ, Croft JB, Liu Y, Lu H, Eke PI, & Ciles WH (2017). Vital signs: Racial disparities in age-specific mortality among Blacks or African Americans — United States, 1999–2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 66(17), 444–456. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6617e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis SK, Liu Y, Quarells RC, & Din-Dzietharn R (2005). Stress-related racial discrimination and hypertension likelihood in a population-based sample of African Americans: the Metro Atlanta Heart Disease Study. Ethnicity & Disease, 15(4), 585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deitch EA, Barsky A, Butz RM, Chan S, & et al. (2003). Subtle yet significant: The existence and impact of everyday racial discrimination in the workplace. Human Relations, 56(11), 1299–1324. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, & Melisaratos N (1983). The Brief Symptom Inventory: An introductory report. Psychological Medicine, 13(3), 595–605. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700048017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagly AH (1987). Sex differences in social behavior: a social-role interpretation. Hillsdale, N.J.: L. Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, Burdette AM, & Hill TD (2009). Blessed assurance: Religion, anxiety, and tranquility among US adults. Social Science Research, 38(3), 656–667. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2009.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch BK, & Vega WA (2003). Acculturation stress, social support, and self-rated health among Latinos in California. Journal of Immigrant Health, 5(3), 109–117. doi: 10.1023/a:1023987717921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford ME, Tilley BC, & McDonald PE (1998a). Social support among African-American adults with diabetes, Part 1: Theoretical framework. Journal of the National Medical Association, 90(6), 361–365. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford ME, Tilley BC, & McDonald PE (1998b). Social support among African-American adults with diabetes, Part 2: A review. Journal of the National Medical Association, 90(7), 425–432. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galster GC, & Carr JH (1991). Housing discrimination and urban poverty of African-Americans. Journal of Housing Research, 2(2), 87–123. [Google Scholar]

- Giger JN, Appel SJ, Davidhizar R, & Davis C (2008). Church and spirituality in the lives of the African American community. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 19(4), 375–383. doi: 10.1177/1043659608322502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamer M, Molloy GJ, & Stamatakis E (2008). Psychological distress as a risk factor for cardiovascular events: Pathophysiological and behavioral mechanisms. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 52(25), 2156–2162. doi: 10.1016/jjacc.2008.08.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JB, & Sandelowski M (2004). Types of social support in African Americans with cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 31(4), 792–800. doi: 10.1188/04.onf.792-800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF, & Matthes J (2009). Computational procedures for probing interactions in OLS and logistic regression: SPSS and SAS implementations. Behavior Research Methods, 41(3), 924–936. doi: 10.3758/brm.41.3.924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez DC, Reitzel LR, Wetter DW, & McNeill LH (2014). Social support and cardiovascular risk factors among Black adults. Ethnicity & Disease, 24(4), 444–450. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C-Y, Hsu M-C, & Chen T-J (2011). An exploratory study of religious involvement as a moderator between anxiety, depressive symptoms and quality of life outcomes of older adults. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21(5-6), 609–619. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03412.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PO, & Neyman J (1936). Tests of certain linear hypotheses and their application to some educational problems. Statistical Research Memoirs, 1, 57–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kendzor DE, Businelle MS, Reitzel LR, Rios DM, Scheuermann TS, Pulvers K, & Ahluwalia JS (2014). Everyday discrimination is associated with nicotine dependence among African American, Latino, and White smokers. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 16(6), 633–640. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, & Williams DR (1999). The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 40(3), 208–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N (2016). Assessing supportive social exchanges inside and outside religious institutions: Exploring variations among Whites, Hispanics, and Blacks. Social Indicators Research, 128(1), 131–146. doi: 10.1007/s11205-015-1022-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, Kosheleva A, Waterman PD, Chen JT, & Koenen K (2011). Racial discrimination, psychological distress, and self-rated health among US-Born and Foreign-Born Black Americans. American Journal of Public Health, 101(9), 1704–1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, & Sidney S (1996). Racial discrimination and blood pressure: The CARDIA Study of young black and white adults. American Journal of Public Health, 86(10), 1370–1378. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.10.1370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, Smith K, Naishadham D, Hartman C, & Barbeau EM (2005). Experiences of discrimination: Validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Social Science & Medicine, 61(7), 1576–1596. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakey B, & Cohen S (2000). Social support and theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lazzarino AI, Hamer M, Stamatakis E, & Steptoe A (2013). Low socioeconomic status and psychological distress as synergistic predictors of mortality from stroke and coronary heart disease. Psychosomatic Medicine, 75(3), 311–316. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182898e6d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis TT, Aiello AE, Leurgans S, Kelly J, & Barnes LL (2010). Self-reported experiences of everyday discrimination are associated with elevated C-reactive protein levels in older African-American adults. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 24(3), 438–443. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.11.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, Chatters LM, & Taylor RJ (2005). Social support, traumatic events, and depressive symptoms among African Americans. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(3), 754–766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mama SK, Li Y, Basen-Engquist K, Lee RE, Thompson D, Wetter DW, … McNeill LH (2016). Psychosocial mechanisms linking the social environment to mental health in African Americans. PLoS ONE, 11(4), e0154035. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maness SB, Reitzel LR, Watkins KL, & McNeill LH (2016). HPV awareness, knowledge and vaccination attitudes among church-going African-American women. American Journal of Health Behavior, 40(6), 771–778. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.40.6.9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR, & Kitayama S (1999). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation In Baumeister RF (Ed.), The self in social psychology. (pp. 339–371). New York, NY, US: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR, & Kitayama S (2001). The cultural construction of self and emotion: Implications for social behavior In Parrott WG (Ed.), Emotions in social psychology: Essential readings. (pp. 119–137). New York, NY, US: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mays VM, Cochran SD, & Barnes NW (2007). Race, race-based discrimination, and health outcomes among African Americans. Annual Review of Psychology, 55(1), 201–225. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merz EL, Roesch SC, Malcarne VL, Penedo FJ, Llabre MM, Weitzman OB, … Gallo LC (2014). Validation of Interpersonal Support Evaluation List-12 (ISEL-12) scores among English- and Spanish-Speaking Hispanics/Latinos from the HCHS/SOL Sociocultural Ancillary Study. Psychological Assessment, 26(2), 384–394. doi: 10.1037/a0035248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossakowski KN, & Zhang W (2014). Does social support buffer the stress of discrimination and reduce psychological distress among Asian Americans? Social Psychology Quarterly, 77(3), 273–295. [Google Scholar]

- Mulvaney-Day NE, Alegria M, & Sribney W (2007). Social cohesion, social support, and health among Latinos in the United States. Social Science & Medicine, 64(2), 477–495. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD, Curtin SC, & Arias E (2017). Deaths: Final data for 2015. National Vital Statistics Reports, 66(6), 1–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance on Mental Illness. (2015). African American Mental Health, from https://www.nami.org/Find-Support/Diverse-Communities/African-American-Mental-Health Accessed on 10/18/18.

- Nguyen NT, Savoy EJ, Reitzel LR, Nguyen M-AH, Wetter DW, Reese-Smith J, & McNeill LH (2017). Diet, alcohol use, and colorectal cancer screening among Black church-goers. Health Behavior and Policy Review, 4(2), 118–128. doi: 10.14485/hbpr.4.2.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obasi EM, Flores LY, & James-Myers L (2009). Construction and initial validation of the Worldview Analysis Scale (WAS). Journal of Black Studies, 39(6), 937–961. doi: 10.1177/0021934707305411 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Obasi EM, & Leong FTL (2009). Psychological distress, acculturation, and mental health-seeking attitudes among people of African descent in the United States: A preliminary investigation. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56(2), 227–238. doi: 10.1037/a0014865 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Obasi EM, & Leong FTL (2010). Construction and validation of the Measurement of Acculturation Strategies for People of African Descent (MASPAD). Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16(4), 526–539. doi: 10.1037/a0021374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odafe MO, Salami TK, & Walker RL (2017). Race-related stress and hopelessness in community-based African American adults: Moderating role of social support. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 23(4), 561–569. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, Fuller-Rowell T, & Burrow AL (2009). Racial discrimination and the stress process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(6), 1259–1271. doi: 10.1037/a0015335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe EA, & Smart Richman L (2009). Perceived discrimination and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 135(4), 531–554. doi: 10.1037/a0016059; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. (2009). A religious portrait of African-Americans. Available from http://www.pewforum.org/2009/01/30/a-religious-portrait-of-african-americans/ Accessed on 10/18/18.

- Pieterse AL, Todd NR, Neville HA, & Carter RT (2012). Perceived racism and mental health among Black American adults: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 59(1), 1–9. doi: 10.1037/a0026208; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prelow HM, Mosher CE, & Bowman MA (2006). Perceived racial discrimination, social support, and psychological adjustment among African American college students. Journal of Black Psychology, 32(4), 442–454. doi: 10.1177/0095798406292677 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reitzel LR, Hiroe O, Hernandez DC, Regan SD, McNeill LH, & Obasi EM (2016). The built food environment and dietary intake among African-American adults. American Journal of Health Behavior, 40(1), 3–11. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.40.1.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitzel LR, Regan SD, Nga N, Cromley EK, Strong LL, Wetter DW, & McNeill LH (2014). Density and proximity of fast food restaurants and body mass index among African Americans. American Journal of Public Health, 704(1), 110–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. (2017). Discrimination in America: Experiences and views of African Americans, from https://www.rwif.org/en/library/research/2017/10/discrimination-in-america--experiences-and-views.html Accessed on 10/18/18.

- SAS Institute. (2013). SAS documentation (Version 9.4). Cary, NC: SAS Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Scholz U, Kliegel M, Luszczynska A, & Knoll N (2012). Associations between received social support and positive and negative affect: evidence for age differences from a daily-diary study. European Journal of Ageing, 9(4), 361–371. doi: 10.1007/s10433-012-0236-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz AJ, Israel BA, Gravlee CC, Mentz G, Williams DR, & Rowe Z (2006). Discrimination, symptoms of depression, and self-rated health Among African American women in Detroit: Results from a longitudinal analysis. American Journal of Public Health, 96(7), 1265–1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seawell AH, Cutrona CE, & Russell DW (2014). The effects of general social support and social support for racial discrimination on African American women’s well-being. Journal of Black Psychology, 40(1), 3–26. doi: 10.1177/0095798412469227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims M, Diez-Roux AV, Dudley A, Gebreab S, Wyatt SB, Bruce MA, … Taylor HA (2012). Perceived discrimination and hypertension among African Americans in the Jackson Heart Study. American Journal of Public Health, 102(S2), S258–S265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, & Nelson AR (2003). Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care Washington D.C.: National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smelser NJ, Wilson WJ, & Mitchell F (2001). America Becoming: Racial Trends and Their Consequences (Vol. 1). Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 10.17226/9599 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Repetti RL, & Seeman T (1997). Health psychology: What is an unhealthy environment and how does it get under the skin? Annual Review of Psychology, 48, 411–447. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson T, Perez M, Kreuter M, Margenthaler J, Colditz G, & Jeffe DB (2017). Perceived social support in African American breast cancer patients: Predictors and effects. Social Science & Medicine, 192, 134–142. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.09.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomfohr L, Cooper DC, Mills PJ, Nelesen RA, & Dimsdale JE (2010). Everyday discrimination and nocturnal blood pressure dipping in Black and White Americans. Psychosomatic Medicine, 72(3), 266–272. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181d0d8b2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Minority Mental Health. (2016). Mental health and African Americans, from https://www.minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/content.aspx?lvl=3&lvlID=9&ID=6474 Accessed on 10/18/18.

- Ware JE Jr., & Gandek B (1998). Overview of the SF-36 Health Survey and the International Quality of Life Assessment (IQOLA) Project. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 57(11), 903–912. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00081-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins DC, Hudson DL, Howard Caldwell C, Siefert K, & Jackson JS (2010). Discrimination, mastery, and depressive symptoms among African American men. Research on Social Work Practice, 27(3), 269–277. doi: 10.1177/1049731510385470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins KL, Reitzel LR, Wetter DW, & McNeill LH (2015). HPV Awareness, knowledge and attitudes among older African-American women. American Journal of Health Behavior, 39(2), 205–211. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.39.2.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Neighbors HW, & Jackson JS (2003). Racial/Ethnic discrimination and health: Findings from community studies. American Journal of Public Health, 93(2), 200–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Yan Y, Jackson JS, & Anderson NB (1997). Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology, 2(3), 335–351. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]