Abstract

Objectives:

“Channel-linked” and “multi-band” front-end automatic gain control (AGC) were examined as alternatives to single-band, channel-unlinked AGC in simulated bilateral cochlear implant (CI) processing. In channel-linked AGC, the same gain control signal was applied to the input signals to both of the two CIs (“channels”). In multi-band AGC, gain control acted independently on each of a number of narrow frequency regions per channel.

Design:

Speech intelligibility performance was measured with a single target (to the left, at −15 or −30º) and a single, symmetrically-opposed masker (to the right) at a signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of −2 decibels. Binaural sentence intelligibility was measured as a function of whether channel linking was present and of the number of AGC bands. Analysis of variance was performed to assess condition effects on percent correct across the two spatial arrangements, both at a high and a low AGC threshold. Acoustic analysis was conducted to compare post-compressed better-ear SNR, interaural differences, and monaural within-band envelope levels across processing conditions.

Results:

Analyses of variance indicated significant main effects of both channel linking and number of bands at low threshold, and of channel linking at high threshold. These improvements were accompanied by several acoustic changes. Linked AGC produced a more favorable better-ear SNR and better preserved broadband ILD statistics, but did not reduce dynamic range as much as unlinked AGC. Multi-band AGC sometimes improved better-ear SNR statistics and always improved broadband ILD statistics whenever the AGC channels were unlinked. Multi-band AGC produced output envelope levels that were higher than single-band AGC.

Conclusions:

These results favor strategies that incorporate channel-linked AGC and multi-band AGC for bilateral CIs. Linked AGC aids speech intelligibility in spatially separated speech, but reduces the degree to which dynamic range is compressed. Combining multi-band and channel-linked AGC offsets the potential impact of diminished dynamic range with linked AGC without sacrificing the intelligibility gains observed with linked AGC.

SHORT SUMMARY

Channel-linked and multi-band automatic gain control (AGC) were explored as alternatives to single-band, channel-unlinked AGC in simulated bilateral cochlear implant processing. Speech intelligibility was measured with a spatially separated speech masker at a signal-to-noise ratio of −2 dB. Performance was assessed for two different AGC thresholds and two different spatial configurations. Statistical analyses showed that channel-linked AGC and multi-band AGC both improved performance. Acoustical analyses suggest a number of potential benefits of these alternative strategies.

I. INTRODUCTION

Speech recognition can be adversely affected by the presence of competing sources in everyday acoustical environments. Intelligibility depends on the number of sources (Hawley et al., 1999), their spatial configurations (Kidd et al., 2010), their degree of temporal (Best et al., 2011) and spectral (Best et al., 2013) overlap, and their stimulus levels relative to one another. It is particularly important to consider what types of masking are present. Background talkers mask speech targets through energetic and informational masking (i.e., Kidd et al, 2016).

The spatial separation of sound sources in the plane of azimuth plane can aid speech recognition. Between-talker differences in interaural time and level differences (ITDs and ILD) tend to provide increased release from masking (Marrone et al., 2008). Across-ear differences in signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) are also beneficial when they allow the listener to attend to the ear with the better SNR.

Normal hearing (NH) listeners can take advantage of interaural differences and better-ear SNR to improve speech intelligibility. The better-ear SNR benefit is particularly robust in speech reception involving sentences (Hawley et al., 1999; Marrone et al., 2008). By contrast, listeners with cochlear hearing loss do not experience the same degree of benefit as NH listeners from the presence of interaural cues (e.g., Moore, 1996). While those who pursue bilateral cochlear implantation may obtain some better-ear SNR benefits, their performance in binaural tasks does not match that of NH listeners (e.g., van Hoesel, 2012). A number of individual subject factors must be considered when evaluating the performances of bilateral cochlear implant (CI) users on binaural and spatial hearing tasks. Those include the nature of the hearing impairment and the amount of time post-implantation (e.g., Poon et al, 2009).

One general problem is that bilateral CI users tend not to receive as much benefit from binaural information as a whole as their NH listening counterparts. Some bilateral CI users have demonstrated some sensitivity to envelope ITDs (van Hoesel & Clark 1997; Laback et al., 2004; Poon et al., 2009), but their sensitivity to fine-structure cues like ITDs is typically poor (Shannon et al., 1995; Laback et al. 2004; Grantham et al., 2008; Brown and Bacon, 2010; Hancock et al., 2010), at least with current clinical processors. Some bilateral CI users have demonstrated relatively good sensitivity to ILDs (Laback et al., 2004; Grantham et al., 2008). The topics of improving the representation of ITDs (Riss et al., 2014; Kan et al., 2015; Monaghan and Seeber, 2016) and ILDs (Brown, 2018) have received considerable attention lately. However, users’ performance on speech tasks involving spatially distributed maskers has been far poorer than that of NH listeners (Kokkinakis & Pak, 2014). For example, speech reception thresholds (SRTs) in a cocktail party setting can be about 20 dB higher for bilateral CI users than for NH listeners (Loizou et al., 2009).

A number of signal-reception and signal-encoding related factors might be improved upon, so that bilateral CI users may achieve improved performance on binaural tasks. Problems include across-device differences in microphone type (Aronoff et al., 2011), timing disparities in left- and right-ear sampling clocks (Kan & Litovsky, 2015), interaural mismatch of electrode placement (Poon et al., 2009; Goupell et al., 2013b; Kan et al., 2013; Kan & Litovsky, 2015), and the worsening of interaural difference statistics by dynamic range processing (Seligman & Whitford, 1995; Byrne & Noble, 1998; Ricketts et al., 2006; Grantham et al., 2007; Dorman et al., 2014).

Dynamic range compression is an area of CI signal processing where improvements might be made. Wide ranges of levels in acoustic signals must be compressed in CIs to accommodate the narrow range that is available at the auditory nerve. This typically takes place through a series of steps (e.g., Dorman et al, 2014). Speech levels on one hand can vary on the order of 50 dB for a talker in everyday environments (Zeng et al., 2002), and baseline talker levels can further vary depending on the nature of the conversation and the amount and type of background noise. Furthermore, ILDs add to the dynamic range when this range is examined binaurally. The encodable dynamic range at the auditory nerve on the other hand has been reported to be as small as about 10–15 dB (Fu & Shannon, 1998; Zeng et al., 2002). This suggests the need for large amounts of amplitude compression for bilateral CI users. It remains unfortunately difficult to achieve such extensive dynamic range compression without degrading the incoming signals. The current study represents an attempt to address the degradation imposed by certain dynamic range processing schemes.

In CIs, dynamic range is often reduced through compression via front-end automatic gain control (AGC; Vaerenberg et al., 2014), back-end mapping (e.g., Khing et al., 2013; Brown, 2014), and/or other innovations like adaptive dynamic range optimization (ADRO) (James et al., 2002; Blamey, 2005). While front-end AGC is typically applied to the higher-intensity portions of input signals (Seligman & Whitford, 1995; Wiggins & Seeber, 2011), other stages of compression, back-end mapping in particular, reduce level differences for both low and high-intensity signals. Different amounts of compression are applied at the different stages. This varies across manufacturers (Vaerenberg et al., 2014), and is also affected by fitting procedures. In typical front-end AGC, input levels exceeding a specified AGC threshold are identified by a peak detector, then the amount of amplitude compression that is applied depends on a pre-determined input/output ratio. The amount of compression depends on the level of the peak detector which operates on windows of time of specified durations (Wiggins & Seeber, 2013). This is different from the back-end mapping systems that employ instantaneous sample-by-sample compression. Some front-end AGC systems employ peak detectors with attack and release time constants that follow faster, syllable-scale fluctuations (Seligman & Whitford, 1995; Boyle et al., 2009; Khing et al., 2013; Vaerenberg et al., 2014). These relatively short time constants allow desired output levels to be achieved after AGC even when the inputs levels fluctuate relatively rapidly. Others employ peak detectors with longer time constants which track slower changes in level, such as those that occur across different backgrounds (Seligman & Whitford 1995; Boyle et al., 2009; Khing et al., 2013; Vaerenberg et al., 2014). In some devices, fast-acting detectors work in parallel with slower-acting ones (e.g., Boyle et al., 2009). Front-end AGC is currently implemented in most devices; while it is currently implemented in the Cochlear Corp., Med-El and Advanced Bionics devices, this is not true for Neurelec devices (Vaerenberg et al., 2014) at this time.

Dynamic range processing imposes a number of challenges on the representation of ILDs, in particular. ILDs are distorted when front-end AGC is independent across the two devices, as is typical in modern-day bilateral CIs. When a single source is presented from off-midline for example, the mean ILD is reduced with independent front-end AGC (Byrne & Noble, 1998, Grantham et al., 2007). With current CI signal processing, gain control commonly acts on the broadband waveforms (e.g., Ricketts et al., 2006; Grantham et al., 2007; Dorman et al., 2014). When ILDs are distorted at a time point for one frequency region with broadband AGC, they are distorted for all the frequencies for that time point. This causes extensive ILD distortion when AGC is independent between the channels. The specific amount of change in the ILD statistics that is brought about by the distortion depends on signal parameters such as signal input level and ILD, and device parameters such as AGC threshold and compression ratio, parameters which have varied across previous studies addressing AGC using syllable-scale time constants (e.g., Boyle et al., 2009; Khing et al., 2013), and in the case of the AGC threshold, can depend on user performance (Vaerenberg et al., 2014). The problem of how best to present ILDs is a challenge for CI design in general and one that extends beyond front-end AGC design. Loudness growth functions with current mapping schemes, for example, do not yield optimal lateralization performance across a range of ILDs and stimulus levels (Goupell et al., 2013a). Current compression schemes distort the representation of interaural differences in bilateral hearing aids, as well as bilateral CIs (Brown et al, 2016).

One potential alternative strategy to conventional front-end AGC, borrowed from studies in the hearing aid literature, is to link the AGC processing across the channels. In one approach, the maximum peak detector signal is selected between the left and right channels at a time point. A gain control signal is derived from this peak detector, then applied equally to both channels, resulting in the least amount of gain (maximum amount of AGC) that was called for given the two individual peak detector signals (Wiggins & Seeber, 2013). One benefit of channel-linked AGC is that it improves the long-term “apparent” better-ear SNR (e.g., the SNR among the signals post signal processing rather than at the stage of the head-related transfer functions; see Wiggins and Seeber, 2013) relative to unlinked AGC for a wide range of spatial configurations with modulating sources. A second benefit is that it reduces the distortion of ILDs (Schwartz & Shinn-Cunningham, 2013; Wiggins & Seeber, 2013) via implant processing. ILDs are never distorted via linked AGC due to how the same gain control signals are always applied to the two channels in this strategy. In a spatial auditory attention task with speech maskers, performance thresholds for target/masker separation were found to be lower with linked than unlinked AGC in simulated hearing aid listening (Schwartz & Shinn-Cunningham, 2013). The authors attributed the improved performance to the better representation of ILD statistics with linked than unlinked AGC. While Wiggins and Seeber (2013) used a two-band strategy, Schwartz and Shinn-Cunningham (2013) used a 16-band strategy.

We reasoned that linked AGC might be a particularly useful strategy to attempt in bilateral CIs, given how relatively important the representation of ILDs might be for these listeners, compared to bilateral hearing aid users. While bilateral hearing aid users can rely on fine-structure ITDs as sources of binaural information, bilateral CI users have relatively limited access to these cues.

A drawback to channel linking as a strategy for bilateral device users however is that linked AGC results in a larger binaural range of output levels than unlinked AGC. This can be particularly problematic given how narrow the dynamic ranges tend to be at the auditory periphery for the users. This point is illustrated in the following example. When a source is presented from off-midline, the broadband level is lower at the far ear than at the near ear prior to AGC. Assume that the levels are reduced at the near ear as a result of front-end AGC. While the source at the far ear (where there is less level reduction than at the near ear) may be audible after unlinked AGC, the level of the source at that ear is reduced relatively more with linked than with unlinked AGC, due to the synchronization with the near ear. The reduced audibility that may result from the introduction of linked AGC may be potentially problematic, for a number of reasons. One problem for example is that speech perception might be affected directly. Another is that spatial perception might be distorted; when the far-ear signal level is reduced to inaudible (with linked AGC), the ILD might then be perceived as infinite instead of finite as could otherwise be the case (with unlinked AGC).

Whether or not the ultimate speech signals are audible for a bilateral CI user depends on two factors: 1), how the levels following the initial AGC stage and the frequency-decomposition steps in CIs relate to the CI’s input mapping ranges (i.e., Vaerenberg et al, 2014), and 2), how the levels following the mapping step relate to the lower end of the electrical dynamic range. The end result is that linking might affect the audibility of some of the speech material if there is not enough compression in the mapping step. While it might seem like an obvious solution to increase the input mapping range then increase the amount of compression in the mapping step, doing so may produce a situation in which the amount of compression is excessive. Speech intelligibility can suffer when the compression ratios are too high (Fu and Shannon, 1998). In light of the limited dynamic range associated with hearing loss, it is unknown whether linked AGC would actually be an effective strategy for bilateral device users in general, bilateral CI users in particular.

It might be possible to use multi-band front-end AGC to mitigate some of the problems that linking poses on dynamic range and audibility in bilateral CIs. In multi-band front-end AGC, separate gain control signals are computed within individual frequency bands, and AGC is applied independently to each band (e.g., James et al., 2002; Stone & Moore, 2003; Zeng, 2004; Blamey, 2005). Level changes are more narrowband-specific in multi-band AGC than in single-band AGC. With level-reducing single-band AGC for example if the energy of a speech signal is in a certain region, then another frequency region containing low but audible energy may be rendered inaudible after gain control processing. This does not happen in multi-band AGC. Given this advantage of multi-band AGC, using this as an alternative to single-band AGC could alleviate issues with audibility caused by an excessively large input mapping range with linked AGC. It is also worth noting that multi-band AGC might also be used as a strategy to offset the problem of how linking adds to dynamic range, for hearing aids as well as bilateral CIs.

Multi-band AGC has been widely studied in unilateral hearing aid (e.g., Plomp, 1988; Yund & Buckles, 1995; Moore et al., 1999; Moore et al, 2011; Strelcyk et al., 2013) and CI (Stone & Moore, 2003; Stone & Moore, 2004; Stone & Moore, 2007; Stone & Moore, 2008) applications. Masked speech intelligibility performance has been shown to improve with the number of bands at an aided ear for hearing aid users (Yund & Buckles, 1995), and the multi-band strategy has been used in conjunction with linked AGC in simulated hearing aid studies (Schwartz & Shinn-Cunningham, 2013).

There are many advantages of multi-band AGC. This strategy may better approximate the natural processing of the auditory system than single-band AGC (Lopez-Poveda et al., 2016). Multi-band AGC also allows for the parameters of AGC to be controlled in a band-specific way. The idea of using multiple bands to control for loudness has been explored extensively in hearing-aids (e.g., Launer and Moore, 2003) and CIs. One technology which utilizes a kind of multi-band compression is ADRO (James et al., 2002; Blamey, 2005), which uses slow compression (20 dB/s time constants) to control for output level on a band-by-band basis and which has led to numerous successful results in speech understanding (Blamey, 2005), including for bilateral CI users (Brockmeyer et al., 2011).

Like linked AGC however, multi-band front-end AGC also has drawbacks. One problem with multi-band AGC is that it decreases spectral and temporal contrasts in the monaural channels (Plomp, 1988; Stone & Moore, 2004; Stone & Moore, 2007; Stone & Moore, 2008). Multi-band AGC also introduces common modulations between the target and masker, which is problematic for vocoded listening applications in particular (e.g., Stone & Moore, 2008), in which the reliance on envelopes is increased. The extent to which the benefits outweigh the drawbacks (for device users, CI users in particular) depends on a number of factors including the degree of temporal fine-structure preservation, compression speed (Stone & Moore, 2003, 2004, 2008), compression ratio and the number of bands (Stone & Moore, 2004, 2008).

While extensive work has been performed to evaluate the effectiveness of multi-band front-end AGC in unilateral hearing aids and CIs, less work has been done on multi-band AGC with bilateral CIs or HAs (Moore et al, 2001; Brockmeyer et al., 2011; Schwartz & Shinn-Cunningham, 2013). Two sets of important questions have not been adequately addressed, to our knowledge. First, not enough is known about the effects of linking and of the number of bands of AGC on speech understanding for bilateral device users, when linking is assumed not to reduce audibility (the hearing-aid related studies addressing the effects of linking aside). Second, not enough is known about the effects of linking and of the number of bands on speech understanding for bilateral device users, when linking is assumed to reduce audibility. Multi-band AGC is particularly appealing for potential use in bilateral CIs, due to how increasing the number of bands offsets the dynamic range related issue that is encountered with linking (i.e., that while linking preserves ILDs, those preserved ILDs must also be taken into account when the range of envelope levels is examined binaurally). Whether or not multi-band AGC is actually advantageous therefore needs to be addressed with real or simulated bilateral CI users, with and without linking.

The purpose of this study was to explore the potential benefits of channel-linked AGC for speech intelligibility in simulated bilateral CI stimulation. Because dynamic range is a limitation for CI users, multi-band AGC was included as a possible method for offsetting how linked AGC does not reduce dynamic range as effectively as unlinked AGC. The effects of channel-linked AGC and multi-band AGC on speech intelligibility were measured with a spatially separated speech masker. Because the current study used NH listeners, there were no inherent limitations to input dynamic range. As a result of this factor especially, we did know whether we would observe benefits from multi-band processing. The multi-band AGC conditions were included nevertheless to assess any possible deleterious effects on performance.

The performance effects of linked and multi-band AGC were measured for two different spatial configurations (±15 or ±30°), in which the target and masker were symmetrical around midline. The spatial configuration was randomly selected from trial to trial to introduce uncertainty to the target location, while still keeping the number of conditions manageable.

Two AGC thresholds were used, one relatively high and the other lower. These two AGC thresholds were chosen to mimic the often-encountered real-life situations in which the AGC thresholds are fixed and the long-term average talker levels are varying, so that the effects of the AGC on the post-compression envelope statistics depend on the long-term average target and masker levels. The high AGC threshold condition was used to mimic the situation in which the long-term average target level is low enough relative to the AGC threshold, such that AGC would rarely be applied. We did not expect performance to be affected by the specific AGC condition when the AGC threshold was high as much as when it was low, for that reason. As such, we chose to perform statistical analyses separately for the two AGC thresholds. To gain a better understanding of the acoustic differences driving the performance effects, we also analyzed the percent-of-time AGC was engaged, better-ear SNR, broadband distribution of ILDs and envelope levels across conditions.

The current study used NH listeners and vocoder simulations to avoid introducing the variability associated with possible confounding individual subject factors like duration of implant use, processing strategy, neural survival, loudness balancing, and current spread. The vocoder approach we used was not without limitations, however. One is the introduction of zero-phase ITDs, delivered by the tonal carriers of the vocoder. While they are fixed at zero and thus do not co-vary with ILD, they would be expected to influence perceived location to some extent, likely reducing the perceived spatial separation between sound sources. There is also likely a relatively constant ITD delivered by the carriers of bilateral CIs, although it is unclear whether those ITDs would actually be usable for the rates typical for CI users. Also note that the vocoder that we used also did not simulate current spread.

II. METHOD

A. Participants

Seventeen NH participants took part in the experiment (16 females, 1 male, mean age = 20 years, range = 4 years). Because all had audiometric thresholds ≤ 20 dB HL at octave and half-octave frequencies between 125 and 8000 Hz, the limited availability of male participants was not deemed an issue. All participants had limited experience in psychoacoustic studies related to spatial hearing, and had no prior exposure to the speech stimuli used in the present study. All procedures were approved by the institutional review board at the University of Pittsburgh. The subjects received either monetary reimbursement or course credit for their participation.

B. Stimuli and signal processing

The target sentences were drawn from the CUNY corpus (Boothroyd et al., 1985), produced by a female talker. The masker sentences were drawn from the IEEE corpus (IEEE, 1969), produced by a different female talker. When the duration of a masker sentence was shorter than that of the concurrent target sentence, multiple masker sentences were concatenated. The raw target and masker sentences were scaled so that the initial overall level of the target would be 69 dB SPL (un-weighted), and the SNR would be −2 dB prior to any head-related transfer function (HRTF) processing.

The scaled target and masker sentences were each convolved with non-individualized (KEMAR) head-related impulse responses (HRIRs) (Gardner & Martin, 1995) from the 0º-elevation set. It is worth noting that the post-convolved levels were different than the pre-convolved/raw-sentence levels. Due to spectral differences between the sentence sets, the masker levels ended up lower than the target levels after the convolution step, even when they were the same before this step. For example, when 10 masker sentences were convolved with the HRIRs for the 0º azimuth/elevation location, the average overall level at a single ear after convolution was about 7.7 dB lower than the pre-convolution levels, while the same analysis on 10 target sentences showed a decrease of only about 2.5 dB. This means that when the pre-convolved SNR was −2 dB, the post-convolved SNR was about 3 dB.

Left/right-channel waveforms were then formed from the sum of the convolved target and masker. The target was always to the left of midline at −15º or −30º in azimuth, and the masker was always to the right at +15º or +30º. Target and masker locations were always symmetrical around midline.

The left/right channel target/masker combined waveforms were processed through a pre-emphasis filter. The pre-emphasis filter was applied to decrease the levels of the low frequencies more than the high frequencies (no energy change at the highest frequency) and better balance the intensity spectrum, as is done with standard CI processing. Although not technically needed for the current study given the NH status of the subject pool, we chose to simulate this aspect of CI processing, given that it might affect results with AGC. The slope was 6-dB per-octave and the cut-off was 50 Hz on the low end (Stone and Moore, 2003; Boyle et al., 2009; Vaerenberg et al., 2014).

After pre-emphasis filtering and before AGC, the stimuli were bandpass filtered with a contiguous series of 6th-order Butterworth filters (Souza & Rosen, 2009). The filter cut-off frequencies were logarithmically spaced between 200 Hz and 5.5 kHz. The low (Dorman et al., 2002; Boyle et al., 2009; Brown & Bacon, 2009) and high (Brown & Bacon, 2009) cut-offs either approximated or matched those used in previous studies. The number of bands in the filter bank was set to equal the number of bands at the AGC stage.

Automatic gain control was applied to one, three, or six frequency bands. The single-band condition was chosen because single-band AGC was also used in previous studies (Seligman & Whitford, 1995; Khing et al., 2013). In the single-band condition, AGC was applied to the broadband signal when levels were above the AGC threshold. In the multi-band conditions, AGC was applied independently to each of the frequency bands.

Automatic gain control was applied in the time domain to each of the bandpass-filtered outputs, as adapted from Wiggins and Seeber (2013). The gain control signal was determined using a peak detector algorithm (Kates, 2008, p. 233). Like other fast front-end AGC studies (e.g., Seligman & Whitford, 1995; Boyle et al., 2009; Khing et al., 2013), the attack and release times (2 ms and 60 ms respectively) were set to respond to syllable-scale fluctuations and corresponded with the time constants of the peak detector. Relatively fast time constants were chosen because the target stimuli were single sentences, and longer time constants are often designed for acoustic environments in which background levels change across multiple talkers. A high compression ratio of 12:1 was used. This ratio matches that employed by Boyle et al., (2009), but is lower than the infinite compression ratio used in some CI systems (Seligman & Whitford, 1995; Khing et al., 2013).

Automatic gain control thresholds used in previous studies have varied considerably (Boyle et al., 2009; Khing et al., 2013), and typically may be adjusted by the CI user in daily life. Two AGC thresholds were used in the present study. The low AGC threshold was 50 dB SPL (relative to the 69 dB SPL pre-HRIR signal level), and the high threshold was 65 dB SPL (again relative to 69 dB SPL). When AGC was applied to more than one band per channel, per-band AGC thresholds were adjusted for bandwidth (increasing by 3 dB with each doubling of bandwidth; see Table I). Therefore, for multi-band AGC, the reported “AGC threshold” in fact represented an average AGC threshold across all bands. Note that this averaged AGC threshold (for three and six-band AGC) was the same as the AGC threshold for single-band AGC. While this may or may not have led to equivalence across bands with respect to the percentage of time in which AGC was “active” (i.e., the percentage of time in which the level of at least one of the signals in a band or channel was sufficiently high enough in level to be affected by AGC activity; Fig 1), it did lead to equivalence with respect to the mean absolute AGC threshold.

Figure 1:

Percent-of-time AGC was engaged as a function of AGC condition, target/masker spatial arrangement and threshold. Note that this value reflects the percentage of time in which AGC activity affected the level of one of the signals, either at one of the bands or one of the two channels.

Following previous studies with simulated hearing aid listeners (e.g., Schwartz & Shinn-Cunningham, 2013; Wiggins & Seeber, 2013), AGC was either linked or unlinked across the channels. In channel-linked AGC, the minimum gain (i.e., at each time point, the gain control signal of either channel that called for the minimum amount of gain, or maximum compression) computed across left and right channels was always applied to both channels, for matched bands. In channel-unlinked AGC, the left- and right-channel gain control signals were computed and applied independently. In the multi-band conditions, output bands were summed following AGC, forming a single output for each channel.

The post-compressed signals were then passed through six-band sinusoidal vocoders (Shannon et al., 1995; Dorman et al., 1997). Pure-tone carriers were used rather than noise bands because they more accurately reproduce envelope time-frequency modulations than noise (Kates, 2011). The decision to use six bands was based on studies showing that vowel and sentence recognition with vocoded stimuli begin to reach asymptote at around six bands (Fu & Shannon, 1998; Stone & Moore, 2003). The input signals to the vocoder were first filtered into six logarithmically spaced bands between 200 and 5500 Hz. In the conditions with six AGC bands, the cutoff frequencies of the vocoder bands matched those used in the AGC stage. The envelopes were then extracted from each band via half-wave rectification and low-pass filtering at either 400 Hz or half the bandwidth, whichever was less, and used to modulate a sinusoidal carrier whose frequency was the arithmetic mean of the given band. The carriers were synchronous in phase with one another. This resulted in small, coherent instantaneous fine-structure ITDs. The problem of how to present fine-structure ITDs in a way that best simulates bilateral CI listening is challenging however. We did not see fine-structure ITD as a major factor with respect to the central questions of this study regarding how front-end AGC condition affects speech intelligibility, given how the original waveform fine structures were discarded, and given the predominant effect that AGC can have on ILDs, in particular. Nevertheless, it is important to note the presence of these ITDs, and even though they are not the focus of the current study, they may have influenced perception and, by extension, performance. In particular, it is conceivable that they may have reduced the perceptual space of listeners, artificially drawing perceived locations closer to midline. The outputs were then summed, and the root-mean-square of the output was equated with that of the pre-vocoded input. From these values, the summed outputs at both left and right sides were scaled by a single factor, so that the presentation level averaged across the ears for the NH listeners would always be comfortable (~60 dB SPL). No efforts were made to compensate for group delays for the individual bands in the band-pass filter stages, of either the AGC or the vocoder.

Signal processing was accomplished using Python and SciPy (Jones et al., 2001). Digital signals were converted to analog with an Echo Gina 3g sound card, using a 44.1 kHz sample rate and 16-bit quantization, and delivered to listeners with AKG K271 headphones.

C. Procedure

Sentence intelligibility was measured in a total of 24 conditions. The parameters were: linking (linked/unlinked), number of AGC bands (one, three, six), AGC threshold (low, high), and target/masker azimuth (±15º, ±30º). Upon each sentence presentation, subjects were asked to repeat aloud the target sentence as accurately as possible. The experimenter recorded the number of keywords correct. Feedback was not provided. No sentence (target or masker) was ever repeated twice to any of the listeners.

Prior to testing, the participants completed a practice block. This consisted of 20 target sentences (10 unprocessed and 10 vocoded) presented in quiet at 0º azimuth, followed by 60 vocoded sentences presented at −30º azimuth at an SNR of 10 dB. A masker was positioned at +30º.

For testing, the subjects were informed that the target talker would appear somewhere to the left of midline, and the masker somewhere to the right. The subjects were instructed to listen to the talker on the left. Ten target sentences representing fifty keywords were presented per condition. The condition order was randomized for each listener.

D. Analyses

We anticipated a priori possible effects of linked AGC and of number of bands in the low-, but not in the high-threshold conditions, and we were otherwise not interested in the effects of AGC threshold per se. As a result, separate within-subjects analyses of variance (ANOVA) were performed for each AGC threshold, to assess whether the number of bands and/or linking affected speech intelligibility, with spatial configuration also included as a main effect. At a given threshold, the main effects and interaction terms involving the number of bands and linking are discussed first, followed by those involving the spatial configuration.

Acoustical analyses were performed for a subset of stimuli to assess the effects of processing condition on percent-of-time of AGC activation, better-ear SNR, interaural differences and dynamic range. Sentences 20–29 from the target and the masker corpora were used. The same pairs of target and masker sentences were always analyzed for all processing conditions; there was no a priori reason to believe that acoustic data would vary across different sentence sets. The percentage-of-time in which AGC was “engaged” or “active” (Fig. 1) was computed as the percentage of time in which AGC affected the level of a signal in a band or channel. AGC was considered active at a time point when the AGC mechanism affected a signal at one of the bands or channels at that time point due the level of that signal being high enough relative to the compression threshold.

Better-ear SNR was calculated by computing simple whole-sentence target and masker RMS values at the output of the vocoder processing stage for each condition. ILD statistics were computed on the broadband targets and maskers, separately, in the ±15º and ±30º conditions. These statistics were computed from RMS values in 20 ms windows (no overlap) after vocoder processing. Histograms were computed with 200 bins between −15 and +15 dB, values which were chosen based on visual inspection. Note that the SNR and interaural difference statistics reflect broadband analyses. To simplify the reporting of ILD distortion, broadband ILDs were used, since reporting band-by-band ILD statistics would have resulted in a prohibitively large number of subplots.

To examine how processing condition affected dynamic range, envelope level histograms for vocoded target sentences were computed on a band-by-band basis in 20 ms windows (no overlap) (Zeng et al., 2002) for a limited set of conditions. Values were computed as dB SPL following calibration to the SPL output of the headphones used in the study. The analysis took into account the non-linear effects of AGC but did not take into account the linear scaling that took place for the experiment so that the outputs would be presented to NH listeners at comfortable levels. Histogram parameters (fifty equally-spaced bins between −50 and 55 dB SPL) were chosen based on visual inspection. 90th and 10th percentile values were computed for the two channels, and ranges were computed from these values as the maximum of the two 90th percentile values minus the minimum of the two 10th percentile values.

Note that when SNR, ILD and envelope level statistics were computed, the gain control signals per channel were derived based on the summed target and masker signals for that (left or right) channel, but then the gain (after linking, if applicable) was applied separately to target and masker (so that the target and masker signals could be tracked, separately).

III. RESULTS

A. Intelligibility effects

The four panels of Fig. 2 show mean sentence intelligibility as a function of processing condition. In each panel, percent keywords correct is plotted against number of AGC bands and channel-linking. Circles represent performance in channel-linked conditions; diamonds represent performance in the unlinked conditions. The panels are organized horizontally by spatial configuration and vertically by AGC threshold.

Figure 2:

Percent keywords correct as a function of AGC condition, target/masker spatial arrangement and threshold. Linked AGC data are shown in filled circles, and unlinked AGC data are shown in un-filled diamonds. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean (SEM).

The low-AGC threshold data are discussed first, the high-threshold data second. Following the description in the methods section, separate 3-factor within-subjects ANOVAs were performed at each threshold, the factors being channel linking (linked or unlinked), the number of bands (1, 3, or 6), and the spatial configuration (maskers at +/− 15 degrees or +/− 30 degrees). As described in the introduction (and in Fig. 1), gain control was not expected to be active nearly as often in the high AGC threshold conditions as in the low threshold conditions.

1. Low threshold

The performance scores at the low AGC threshold tended to be higher with linked AGC than with unlinked AGC (upper panels of Fig. 2). The results of a within-subjects 3-way ANOVA between linking, number of bands and spatial configuration at low threshold showed a significant main effect of channel-linking [F(1)=34.53, p<0.001], supporting this observation.

Performance also tended to improve with an increasing number of bands at low threshold (upper panels of Fig. 2); within-subjects 3-way ANOVA indicated a significant main effect of the number of bands [F(2)=7.414, p=0.002] at low threshold. The effect of multi-band AGC on the performance average was small, however. Along these lines, when pairwise Tukey comparisons with Bonferroni Corrections were run, none of the comparisons between numbers of bands showed significance in either the low compression threshold linked (p=0.561, p=0.998 and p=0.579) or low-threshold unlinked (p=0.154, p=0.724, and p=0.070) conditions, for band pairs 1–3, 3–6, and 1–6, respectively.

The two-way interaction between channel-linking and number of bands was not found to be statistically-significant [F(1,2)=1.423, p=0.2558] at the low AGC threshold. This result was not overly surprising when viewing the data plotted in Fig. 2; while it is clear that there was no co-variation in the effects of linking and bands at ±15º, the lack of co-variation is less obvious at ±30°.

A significant main effect of spatial configuration was also found at low threshold in the 3-way ANOVA [F(1)=56.02, p<0.001], indicating statistically significantly better performance when there was more spatial separation than less. None of the two-way interactions involving spatial configuration as a factor were found to be statistically-significant, including the terms between spatial configuration and linking [F(1,1)=p=0.504], between configuration and number of bands [F(1,2)=1.049, p=0.3619], and the three-way interaction [F(1,1,2)=0.522, p=0.598]. These results suggest that the underlying factors driving the performance benefits for linked AGC versus multi-band AGC were largely orthogonal.

2. High threshold

It can be observed from the data plotted in the lower panels of Fig. 2 that percent correct tended to be higher for linked than unlinked AGC, even at the high AGC threshold. The results of the within-subjects three-way ANOVA at high threshold indicated a significant main effect of channel-linking at high threshold [F(1)=16.51, p<0.001]. While the magnitude of this statistical effect was smaller than that found for the low-threshold conditions, the results suggest that channel-linking improved performance when threshold was high.

Despite a slight upward trend in the data as number of bands increase from 1 to 6, no significant main effect was found for number of bands at high threshold [F[2]=2.072; p=0.142] in the ANOVA.

No statistically-significant interaction effect was found between channel linking and number of bands [F(1,2)=2.588, p=0.091].

A significant main effect of spatial location was found [F(1)=33.73, p<0.001], with performance in the more spatially-separated configurations improved relative to the less spatially-separated configurations. No statistically-significant interaction terms involving spatial location were found at high threshold, however. This included the interactions between spatial configuration and linking [F(1,1)=0.666, p=0.4264], spatial configuration and the number of bands [F(1,2)=0.7431, p=0.4837], and the three-way interaction [F(1,1,2)=0.526, p=0.596]. These results indicate that the factor(s) that led to the spatial benefit did not co-vary with one another.

B. Better-ear apparent SNR effects

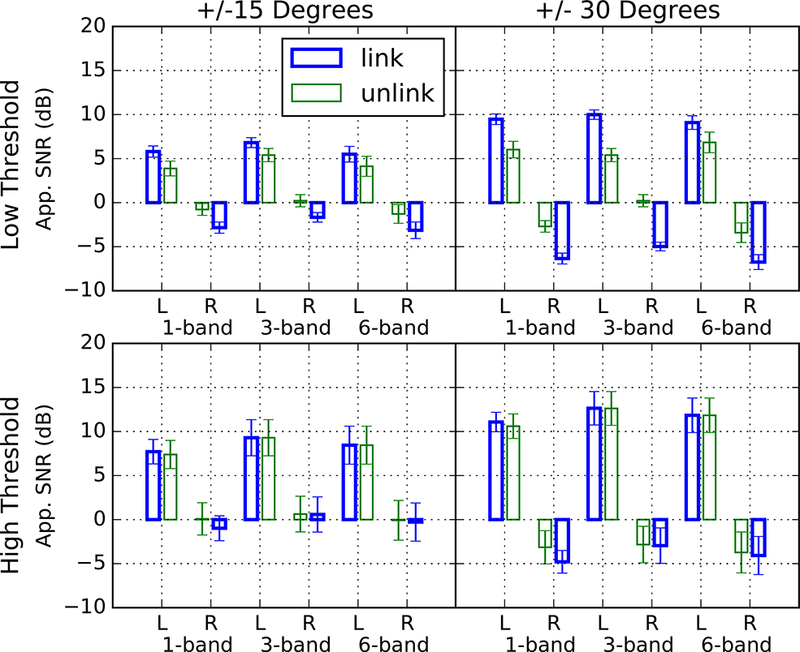

Fig. 3 shows long-term apparent SNRs at the left (ipsilateral to the target) and right (contralateral to the target) ears, as a function of AGC condition and target/masker spatial configuration.

Figure 3:

Apparent SNR statistics at the better (L) and poorer (R) ears, as a function of spatial arrangement and processing condition. Data for the ±15º condition are on the left, and those for the ±30º condition are on the right. Low threshold data are in the upper panels and high-threshold data are in the lower panels. SEM error bars represent variability across individually-computed SNR values.

1. Low threshold

As can be seen in Fig. 3, channel linking led to an overall mean increase in better-ear SNR of 2.1 dB across the low AGC threshold conditions. Linking had the largest effect in the one-band condition (mean increase of 2.7 dB), and smaller effects in the three-band (mean increase of 1.9 dB) and six-band conditions (mean increase of 1.8 dB) at this AGC threshold.

Similar effects of multi-band AGC on better-ear SNR were seen in the linked and unlinked conditions at low threshold. Relative to single band AGC, better ear SNR increased by 1.2 dB with three-band AGC and decreased by 1.1 dB with six-band AGC.

2. High threshold

There was very little effect of linking (0.1 dB on average) at the high AGC threshold. This was expected because gain control is engaged so infrequently at the high threshold used. Similar effects of multi-band AGC on better-ear SNR were seen in the linked and unlinked conditions. Relative to single band AGC, better-ear SNR increased by 1.8 dB with three-band AGC and decreased by 0.8 dB with six-band AGC.

C. Broad-band ILDs

Fig. 4 shows broadband ILD histograms as a function of AGC condition for the ±30º spatial arrangement (processing-condition effects were similar for the ±15º spatial arrangement).

Figure 4:

Broadband ILD histograms for target and masker in the ±30º degree spatial condition, as a function of AGC condition. Within each panel, histogram for target is on the right, and that for masker is on the left. The line for the target is twice as thick as that for the masker.

1. Low threshold

The ILD values for the two sources are more tightly distributed around the means for the sources in the linked conditions than in the unlinked conditions (Fig 4). Also, the mean absolute ILD values are greater in the linked conditions as compared to unlinked (Fig 4). When the histogram data for the linked AGC conditions are fit with normal distributions, the target means and standard deviations (μ±σ) were 7.2 ± 1.3 dB, 7.0 ± 1.3 dB and 7.1 ± 1.4 dB, for the 1-, 3-, and 6-band conditions, respectively.

Multi-band AGC had an apparent effect of reducing ILD variability at the low AGC threshold, but only in the unlinked conditions. This is shown across the panels in the second row of Fig. 4 by the increased prominence of a mode as the number of bands increases. This tendency was corroborated by the corresponding reduction in variability observed with increasing number of bands when the histogram data were fitted with normal distributions, which showed target means and standard deviations (μ±σ) in unlinked AGC and at low threshold to be 6.3 ± 4.6 dB, 5.9 ± 3.1 dB and 5.7 ± 2.7 dB for one, three and six bands, respectively.

2. High threshold

The ILD values for the two sources are relatively-tightly distributed around the mean in most of the linked and unlinked conditions, as expected, and visual inspection shows distributions that appear similar to those in the low-threshold linked conditions (top row of Fig. 4).

D. Envelope levels at low threshold

Fig. 5 illustrates the post-compressed levels of target speech in each of the six vocoder bands at the low AGC threshold in the ±30º spatial configuration. Envelope levels are plotted on the x-axis, and percent occurrence is plotted on the y-axis. Within each panel, values for the left (ipsilateral to target) ear are shown by the thick blue plot; those for the right (contralateral to target) ear are shown by the thin red plot.

Figure 5:

Target envelope level histograms for the single-band and six-band AGC conditions, for channel-linked AGC and channel-unlinked AGC, when the AGC threshold was low and arrangement was +−30º. Histograms are plotted for vocoder-stage envelopes. Histograms for one-band AGC are plotted in the upper panels, and those for six-band AGC are plotted in the lower panels. The histograms for the linked conditions are plotted directly above those for the unlinked conditions. Within each panel, histograms are plotted for the left ear (thick blue trace) and right ear (thin red trace). 10th and 90th percentile values indicated with the dashed lines, the 50th percentile values in the solid lines. Note that “Band 1” refers to the lowest-frequency band and “Band 6” the highest-frequency band.

The range of output target levels for linked AGC was not reduced to the extent that it was for unlinked AGC. This observation is supported by inspection of the 90th percentile/10th percentile range values (averaged across ears) presented in Table II for this condition. The 90th percentile/10th percentile ranges are higher both for the 1-band and 6-band conditions for linked (40.2; 44.9) than unlinked (37.7; 42.3). This suggests that linked AGC might be problematic with respect to dynamic range in that it can lead to poorer target audibility than unlinked AGC, at least for this condition.

While multi-band AGC (90/10 levels of 42.3; 44.9 for unlinked and linked) did not reduce dynamic range as much as single-band AGC (37.7; 40.2 90/10 levels), it led to higher output levels than single-band AGC. The 10th percentile values at the two ears for single-band AGC (−9.0, −8.3, −12.4, −12.1) were all lower in dB SPL than those for multi-band AGC (0.5, −6.7, −7.0, −9.3). This suggests that multi-band AGC might be effective in off-setting the problem encountered with linked AGC (compared to unlinked AGC) with respect to target inaudibility.

To summarize the acoustic findings, channel linking improved better-ear SNR and ILD statistics, but unfavorably increased target dynamic range. Multi-band AGC had mixed effects on better-ear SNR (3 bands led to a slight improvement relative to one band, 6 bands led to a slight decrement relative to 3 bands), favorably reduced ILD variability (but only in unlinked conditions), and led to more favorable target levels in both linked and unlinked AGC.

IV. DISCUSSION

This is the first known study that attempted to examine the effects of channel-linked and/or multi-band front-end AGC on masked speech intelligibility with bilateral CI users in mind. Fast time constants were used, which follows previous hearing-aid (e.g., Wiggins & Seeber, 2013) and CI studies (e.g., Seligman & Whitford, 1995; Boyle et al., 2009; Khing et al., 2013), and also allows front-end AGC peak detectors to respond to amplitude fluctuations on the approximate time scales on which the most common modulations in speech typically occur.

The current study found with simulated bilateral CI processing that channel-linked AGC significantly improved masked speech intelligibility at both low and high AGC thresholds when the target and masker were symmetrically-opposed. Multi-band AGC improved the performance when the AGC threshold was low, but not when it was high. Our results suggest that CI signal processing strategies that combine aspects of channel-linking and multi-band AGC using fast time constants are worthy of consideration as an alternative to single-band, channel-unlinked AGC for bilateral CI stimulation. Multi-band channel-linked AGC may in fact be more important for actual CI users than in our CI simulation, because we didn’t simulate the effects of inaudibility in our study.

It was hypothesized prior to this study that linked AGC might improve masked speech intelligibility compared to unlinked AGC, since it was known that dynamic range was not going to be a limiting factor given the NH of the participants. The potential impact of multi-band AGC was less certain. This strategy had the potential positives impacts of 1), limiting the dynamic range while still allowing the benefits of linking and 2), reducing ILD broadband distortion but the potential negative impacts of 1) flattening the intensity spectrum, thereby reducing spectral contrast, and 2), introducing common modulations between the target and maskers. Since the first potential positive impact was not a factor in the current study given that dynamic range was not a limiting factor for the NH listeners, the lack of a negative outcome with respect to multi-band AGC is considered a positive result. The potential effects of multi-band AGC for bilateral CI listeners remain unevaluated. Yet the current results suggest that further work is needed on linked AGC for real or simulated bilateral CI or bilateral hearing aid users.

A. Channel linking improved masked speech intelligibility performance for simulated bilateral CI listening

The channel-linked AGC strategy was borrowed from hearing aid studies (Wiggins & Seeber, 2013; Schwartz & Shinn-Cunningham, 2013). Recall that while Wiggins & Seeber (2013) tested the effectiveness of this strategy in two-band AGC, Schwartz & Shinn-Cunnigham (2013) did so for 16-band AGC. The effectiveness of this strategy was examined for simulated bilateral CI users in this study, for two reasons. First, it was expected to improve better-ear SNR in dual-source/dual-hemifield arrangements (Wiggins & Seeber, 2013). Second, it was known that it would preserve ILDs (Wiggins & Seeber, 2013; Schwartz & Shinn-Cunningham, 2013). The acoustic analysis revealed that linked AGC did, in fact, improve both better-ear SNR (Fig. 3) and broadband ILD statistics (Fig. 4) compared to unlinked AGC, at least in the spatial configurations used in the current study. It is not surprising given these acoustic outcomes that linked AGC also improved masked speech intelligibility compared to unlinked AGC in the current study. The performance improvements found with linked AGC were statistically significant regardless of whether the AGC threshold was low or high (Fig. 2). Up to 20 percentage-point improvements to speech intelligibility were found at the low threshold, and relatively large improvements were found at that threshold regardless of the number of bands. Also note that the interaction terms between linking and number-of-bands were not statistically-significant at either of the two thresholds. This suggests that linked AGC might be a viable strategy regardless of the number of processing bands in which it is implemented, within reason.

The results of this study suggest that linked AGC is worthy of consideration for bilateral CIs, despite the drawback that it did not reduce dynamic range as effectively as unlinked AGC (Fig. 5). Given that linked AGC also improved better-ear SNR and ILD statistics, the results suggest that those acoustical factors should be considered in bilateral CI design in general.

B. Multi-band AGC improved or did not change masked speech intelligibility performance for the simulated bilateral CI users

Recall that while multi-band AGC has been used in numerous studies in the hearing aid and CI literature, its study in a bilateral context has been limited. No past studies to our knowledge have tested the effects of the number of bands on speech intelligibility performance with speech maskers for real or simulated bilateral hearing aid or bilateral CI users, for example. Multi-band AGC was added to the present study for two reasons. First, it was suspected that it would preserve ILDs better than single-band AGC when AGC is unlinked. This suspicion was confirmed through the broadband ILD analysis plotted in Fig. 2. Second, it was thought that multi-band AGC would reduce dynamic range more effectively than single-band AGC due to its band-specific nature. To this point, observe that the 10th-percentile post-AGC target envelope levels were lower for single-band AGC than for multi-band AGC (Table II) in the low-threshold, ±30° condition, regardless of whether or not AGC was linked. Given these reasons, it appears that multi-band AGC may hold promise as a way of off-setting some of the harmful effects on dynamic range observed with linking.

It was not known however whether multi-band AGC would actually improve performance for simulated bilateral CI users. The advantages of multi-band AGC have to be weighed against the potentially harmful effects of multi-band AGC that have been found with simulated CI users (e.g., Stone & Moore, 2008). Specifically, multi-band AGC produces common modulations between competing sources, and increasing the number of bands also reduces spectro-temporal contrast (Stone & Moore, 2003; Stone & Moore, 2004; Stone & Moore, 2008), particularly when the time constants are fast (Plomp, 1988; Stone & Moore, 2007).

Speech intelligibility improved with multi-band AGC at the low AGC threshold, suggesting that some of the advantages found at this AGC threshold (ILD preservation when AGC is unlinked and improved SNR for some cases) outweighed the disadvantages. Equally importantly, it did not change with the number of bands at the high AGC threshold. Finally, it was not affected by the number of bands for any of the sub-conditions (linked or unlinked AGC) at low threshold. While increasing the number of bands in AGC was known to have produced improved performance for hearing aid users (Yund & Buckles, 1995), it was not known what would happen for bilateral CI users given the lack of known study on the effect of the number of bands for bilateral hearing aid users, and the problems pointed out in the Stone and Moore studies. It is encouraging that the drawbacks of multi-band AGC were not enough to engender performance declines for the multi-band strategy in the current study, even when the known potential advantages of multi-band AGC were expected to be minimal in this study.

No hard-limits were placed on output dynamic range following AGC and vocoding in this study. Multi-band AGC led to higher output levels than single band AGC, in the ±30º condition at low threshold at least. Given that no hard-limits were placed on output dynamic range following AGC and vocoding in this study, this suggests that multi-band AGC might be particularly favorable when the audible dynamic range is limited so that audibility becomes more of an issue. The audible dynamic range is limited for those with more severe losses in general, bilateral CI and hearing aid users, in particular.

It should be noted that the promising results found for multi-band AGC (i.e., that multi-band AGC did not hurt performance) were obtained with fast front-end time-constants. This result appears to contradict the argument that increasing the number of bands in AGC might be detrimental for bilateral device users when the time-constants are fast (Plomp, 1988; Stone & Moore, 2007). The current study’s result suggests that multi-band front-end AGC might be beneficial for bilateral CIs with a variety of time-constants, as relatively large bilateral benefits have already been found for bilateral CI users with multi-band ADRO using slower time constants (Brockmeyer et al., 2011). The study of a multi-band approach with both fast and slow time-constants is warranted given the need to incorporate elements of fast and slow compression into bilateral CIs (Seligman & Whitford, 1995; Boyle et al., 2009).

C. Contributions of acoustic factors to performance benefits

1. Linked AGC

The current study builds on two previous studies that had provided evidence that masked speech intelligibility might improve for simulated bilateral CI users with channel-linked front-end AGC when performance is tested with symmetrically-opposed interferers. That is, it was previously hypothesized that linking might lead to performance improvements in general either due to improved better-ear apparent SNR (Wiggins & Seeber, 2013) or to improved ILD preservation (Schwartz & Shinn-Cunningham, 2013). Linked-AGC led to improved apparent better-ear SNR and reduced broadband ILD variability in the current study, particularly when the AGC threshold was low.

While it was hoped that the speech intelligibility benefit that was found with linking could be attributed to a single factor, it was difficult to do so because the speech intelligibility improvements often co-varied with apparent better-ear SNR and ILD variability improvements. When comparing the low and high-threshold data, for example, speech intelligibility, better-ear SNR and ILD variability improvements with linking were all found to be more pronounced at the low AGC threshold than at high threshold. Also observe that these improvements all tended to be larger for the single-band condition than for the multi-band conditions when the AGC threshold was low.

It is worth noting an unexpected result in the speech intelligibility data when AGC was linked. Although the effect of bands was not statistically-significant at high threshold, a noticeable benefit was found for the three-band condition at the high AGC threshold. The better-ear SNR and broadband ILD variability statistics were not affected very much by linking in this condition. Given these results, it is possible that some relatively subtle ILD distortion effects (unexplained by broadband ILD statistics) might have been important in this condition. It might therefore be beneficial to measure perceived source widths in the different low and high AGC threshold conditions, to see how the widths relate to ILD variability statistics.

2. Multi-band AGC

While increasing the number of bands significantly affected performance at low threshold, strong evidence could not be found to disambiguate whether the effect was due to improved broadband ILD statistics or improved better-ear SNR statistics. The ILD statistics improved with increasing numbers of bands when AGC was unlinked. Better-ear SNR also tended to improve with number of bands. Both could have been factors for the reported speech intelligibility improvement.

There appears to have been weak evidence that reduced ILD distortion with multi-band AGC might have been important, however. Multi-band AGC led to significantly improved speech intelligibility when the AGC threshold was low (where ILD variability was highly affected by the number of bands in unlinked AGC) but not at high threshold (where ILD variability was less affected). The argument was strengthened by the qualitatively similar SNR improvements at the two thresholds for multi-band AGC.

3. Considerations with respect to compression speed and stimulus choice

The compression speed can impact the way in which instantaneous SNRs and ILDs are affected by front-end AGC, potentially interacting with factors like the attack and decay rates of the stimuli themselves. The problem of how unlinked AGC affects more objective judgments like perceived source width and more subjective judgments like movement, blurriness or split images is a complex one that might be dependent on the compression speech and stimulus choice, as well as the number of AGC bands. While work has been performed to assess the effects of front-end AGC on spatial perception for simulated hearing-aid users (Wiggins & Seeber, 2011; Wiggins & Seeber, 2012), little has been done to our knowledge to assess the effects of front-end AGC on these factors for simulated bilateral CI users.

D. Potential application to other target-masker arrangements for bilateral CI users

An important question still outstanding is whether the performance benefits found with linked or multi-band AGC are generalizable to other spatial arrangements. One important case is that in which the target and the masker originate from within the same frontal-hemifield. Note that the AGC effects are very different for this arrangement than the dual-hemifield arrangements used in the current study. First, while linked-AGC affects near-ear (the ear nearer the target) SNR in dual-hemifield arrangements, the effects on near-ear and far-ear SNR are not so pronounced in single-hemifield arrangements due to the lack of differential head-shadow effects in these arrangements. Second, note that the target ILD distortion patterns are quite different across the two types of arrangements. In dual-hemifield arrangements, unlinked AGC reduces target ILD when target is high but increases target ILD when masker is high, while in single-hemifield arrangements, unlinked AGC always reduces target ILD. Differing patterns of condition effects for linked and multi-band AGC might therefore be found across the single and dual frontal-hemifield arrangements with simulated bilateral CI users. Other important cases are those in which there are more than two sound sources, since the complexity of ILD distortion patterns with unlinked AGC increases with added sources (Schwartz and Shinn-Cunningham, 2013).

E. Generalizability across SNRs in dual-hemifield arrangements for bilateral CI users

It is not clear whether or not the benefits observed in the current study with linked or multi-band AGC would have generalized to other input SNRs. Of course, the effects of SNR are subject to floor and ceiling constraints of signal level, and the effects of those SNRs between floor and ceiling might be different for actual (Loizou et al., 2009) versus simulated bilateral CI users given that actual CI users are faced with a number of additional issues including current spread (Bierer, 2010).

Notwithstanding these issues, however, there are several reasons to expect linked AGC to improve performance over unlinked AGC independent of SNR. First, if better-ear apparent SNR is a factor for the linked AGC benefit, then the benefit should be relatively robust to SNR between ceiling and floor. When pilot simulations were conducted for the ±30º arrangement with single-band AGC at the low AGC threshold for single target and masker sentences for example, the SNR benefit with linked AGC changed over only about 2.5 dB (from 1.1 to 3.7 dB) when the SNR varied from 10 dB to −10 dB. Second, if ILD distortion is a factor, then it should be considered that linked AGC preserves ILDs at all SNRs. Finally, it can be assumed that multi-band AGC (given our experimental design) would always produce higher output levels than single-band AGC, regardless of SNR based on what is known about the acoustic effects of each of the processing conditions.

F. Audibility considerations for bilateral CI users

It was assumed in this study that the outputs of the front-end AGC and vocoding were always audible for the listeners. The audibility-assumption is not necessarily valid for bilateral CI users however given that their dynamic range is so limited (e.g, Fu & Shannon, 1998). Audibility might be an important factor for masked speech intelligibility and masked sound localization, both. The reason is that dynamic perceivable ILD changes might be produced with linked AGC when a modulated source like speech is low enough in overall level that the level at the contralateral ear moves above and below the audibility threshold, therefore potentially creating dynamic ILDs, varying between finite and ‘infinite’.

In a similar way, dynamic ILD changes can be elicited in unlinked AGC when the overall level of amplitude-modulated signals is high enough that the level in the ipsilateral ear moves above and below the front-end AGC threshold. In some respects, these two problems represent two sides of a coin. That is, while linking solves the front-end AGC/ILD distortion problem it adds to the inaudible-threshold problem.

The audibility problem could, in theory, be solved by increasing the input mapping range in CIs. Doing so however might not facilitate better speech understanding. Expanding the input mapping range to accommodate linking would require further increases in compression ratios and/or require very-fast compression time constants, which have been shown to have a negative effect on speech understanding (Fu & Shannon, 1998; Stone & Moore, 2003).

The current study was undertaken in part to begin to address the feasibility of multi-band processing as a way of alleviating the audibility problem, which is exacerbated by linked AGC. The results in this study motivate further investigation to better understand how linked and multi-band AGC affect speech intelligibility performance when output dynamic range is hard-limited. It is not known, for example, whether ILD preservation is more important near the front-end AGC threshold or the inaudible threshold. Innovative dynamic range compression strategies may be needed which both reduce ILD distortion relative to unlinked AGC but also compress to reduce dynamic range to avoid inaudibility issues.

G. Relevance for bilateral hearing aid users

While it had previously been established that channel linking could lead to speech intelligibility benefits for simulated bilateral hearing aid users, the results of the current study suggest that some caution is warranted with respect to potential outcomes for actual bilateral hearing aid users. Given that linked AGC did not reduce dynamic range as effectively as unlinked AGC for the spatial arrangements tested in this study, it is reasonable to think it might impose audibility problems for bilateral hearing aid users, particularly those with severe hearing losses for whom dynamic range is particularly limited (Peterson et al., 1990; Moore et al, 1992; Moore et al, 1999). Further study is therefore warranted on the effects of linked AGC for actual bilateral hearing-aid users, when the dynamic range is limited.

The effects of different gain algorithms in multi-band AGC have been studied in bilateral hearing aid users (Moore et al, 2001). This is no surprise, given how speech intelligibility performance has been shown to improve with the number of bands at an ear for hearing aid users (Yund & Buckles, 1995). Multi-band AGC has been used with linked AGC in simulated hearing aid users (Schwartz & Shinn-Cunningham, 2013), as well. Less clear however, is the extent to which increasing the number of bands in AGC would be more advantageous for speech intelligibility in a bilateral, rather than a unilateral context, for hearing aid users. Along these lines, no studies to our knowledge have investigated the multi-band strategy in bilateral hearing aids, specifically as a means of off-setting some of the issues that are encountered with linking. Further study is clearly warranted to establish the effects of increasing the number of bands in AGC for bilateral hearing aid users, in both linked and unlinked contexts. It might be interesting to do so, given how multi-band AGC improved speech intelligibility performance at low AGC threshold for the listeners in the current study, and did so as well in unilateral hearing aid contexts in the Yund & Buckles (1995) study. On one hand, ILD preservation (an advantage of multi-band AGC, when AGC is unlinked) might be less of a factor for bilateral hearing-aid users (for whom original fine-structure/ITD is better preserved) than bilateral CI users (Stone & Moore, 2007). On the other hand, multi-band AGC might be beneficial in off-setting some of the detrimental effects of linking for those listeners.

V. CONCLUSIONS

Conventional front-end AGC distorts ILDs when applied to broadband waveforms independently across devices. The present study addressed this problem by examining the effects of channel-linked AGC as an alternative to this strategy. Performance improvements were found for this alternative strategy in the simulated bilateral CI listening conditions of this study, at both a low and a high compression threshold. The acoustical data confirmed that both better-ear SNR and ILD statistics improved with linked AGC. The acoustical analysis however also demonstrated that linked AGC has harmful effects on output dynamic range for those with smaller dynamic ranges at the auditory periphery. The detrimental effects of linked AGC on dynamic range were largely mitigated by the use of multi-band AGC, a second alternative to single-band unlinked AGC. This strategy, like linked AGC, produced both performance benefits and improved ILD statistics in the acoustical analysis. While further study is needed to test the effects of linked AGC and multi-band AGC with other spatial arrangements and SNRs, there are reasons to expect the benefits to be relatively generalizable.

The acoustical and behavioral results of our study, when taken together, suggest that the combined effects of linked and multi-band front-end AGC should be studied in limited dynamic range listening, with real CI listeners in particular. Our favorable results for linking and multi-band AGC suggest that the optimal overall compression strategy (also incorporating elements like ADRO and back-end mapping) would include elements of both the linking and multi-band strategies. On a final note, observe that our results support that some combination of linked and multi-band AGC might also be beneficial for bilateral hearing aid users.

TABLE I:

Low and high compression thresholds for one-, three-, and six-band AGC. Thresholds are relative to 69 dB target and 71 dB masker, pre-processing.

| 1 band |

3 bands | 6 bands | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Threshold (dB) | Low | 50.0 | 45.2 | 50.0 | 55.5 | 44.0 | 46.4 | 48.8 | 51.2 | 53.6 | 56.0 |

| High | 65.0 | 60.2 | 65.0 | 70.5 | 59.0 | 60.4 | 63.8 | 66.2 | 68.6 | 71.0 | |

TABLE II:

10th and 90th percentile envelope levels at left and right ears (90th L/90th R/10th L/10th R)

| Band | 1-band unlink | 1-band link | 6-band unlink | 6-band link |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 14.8; 13.3; −1.5; −5.0 | 13.3; 11.1; −3.6;−3.5 | 21.1; 19.0; −19.3; 2.3 | 21.1; 19.0; −19.3; −22.1 |

| 2 | 20.9; 19.6; −6.1; −9.2 | 19.6; 16.6; −21.1; −24.2 | 28.5; 24.7; −14.4;−2.1 | 28.5; 24.6;−14.4; −17.6 |

| 3 | 26.2; 23.0; −17.1; −24.7 | 25.7; 20.1; −19.4; −25.0 | 35.6; 29.9; −14.3;−2.4 | 35.6; 29.6; −14.5;−20.3 |

| 4 | 34.5; 32.3; −3.4; −11.1 | 34.1; 29.1; −6.2; −12.5 | 40.0; 38.0; −0.9;−20.3 | 39.9; 35.1; −1.9; −7.6 |

| 5 | 41.2, 38.8; 5.1; −4.1 | 40.9; 33.5; 2.7; −4.5 | 45.9; 43.4; 6.8; −7.5 | 45.9; 38.6; 6.0; −1.7 |

| 6 | 34.3; 30.0; 4.1; −4.1 | 33.6; 25.8; −0.6; −9.8 | 42.8; 36.5; 3.0; 8–1.6 | 42.6; 34.2; 2.1; −7.0 |

| Mean | 28.7; 26.2; −9.0; −8.3 | 27.8; 24.4; −12.4;−12.1 | 35.6, 31.9; 0.5; −6.7 | 35.6; 30.2; −7.0, −9.3 |

| 90/10 Range (averaged across ears) | 37.7 | 40.2 | 42.3 | 44.9 |

VI. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Bernhard U. Seeber for providing the automatic gain control algorithm on which our implementation was based, and Joshua S. Stohl for his helpful feedback on this manuscript. We also thank Katrina Killian and Lauren Dubyne for their work in coordinating data collection. This work was supported by NIDCD (Brown R-01 DC008329) and University of Pittsburgh T-32 Training Grant (T32-DC011499).

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures/Conflicts of Interest:

The authors have no conflicts of interest or finance to disclose.

VII. REFERENCES

- Aronoff JM, Freed DJ, Fisher LM, et al. , (2011). The effect of different cochlear implant microphones on acoustic hearing individuals’ binaural benefits for speech perception in noise. Ear Hear., 32, 468–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best V, Mason CR, Kidd G (2011). Spatial release from masking in normally hearing and hearing-impaired listeners as a function of the temporal overlap of competing talkers. J. Acoust. Soc. Am, 129, 1616–1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierer J, (2010). Probing the electrode-neuron interface with focused cochlear implant stimulation. Trends Amplif., 14, 84–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blamey PJ, (2005). Adaptive dynamic range optimization (ADRO): a digital amplification strategy for hearing aids and cochlear implants. Trends Amplif., 9, 77–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boothroyd A, Hanin L, Hnath T. (1985). A sentence test of speech perception: reliability, set equivalence and short term learning. (Internal No. RCI 10) New York: Speech & Hearing Sciences Research Center, City University of New York. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle PJ, Büchner A, Stone MA, et al. , (2009). Comparison of dual-time-constant and fast-acting automatic gain control (AGC) systems in cochlear implants. Int. J. Audiol, 48, 211–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockmeyer AM, Potts LG, Brockmeyer A, (2011). Evaluation of different signal processing options in unilateral and bilateral cochlear freedom implant recipients using R-space background noise. J. Am. Acad. Audiol, 22, 65–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AD, Rodriguez FA, Portnuff CDF, et al. , (2016). Time-varying distortions of binaural information by bilateral hearing aids: effects of nonlinear frequency compression. Trends Hear., 20, 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CA (2014). Binaural enhancement for bilateral cochlear implant users. Ear Hear., 35, 580–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CA, Bacon SP (2009). Low-frequency speech cues and simulated electric-acoustic hearing. J. Acoust. Soc. Am, 125, 1658–1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CA, and Bacon SP (2010). “Fundamental frequency and speech intelligibility in background noise,” Hear Res, 266, 52–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CA (2018) Corrective binaural processing for bilateral cochlear implant patients. PLoS ONE 13, e0187965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne D, Noble W (1998). Optimizing sound localization with hearing AIDS. Trends Amplif., 3, 51–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorman MF, Loizou PC, Rainey D (1997). Speech intelligibility as a function of the number of channels of stimulation for signal processors using sine-wave and noise-band outputs. J. Acoust. Soc. Am, 102, 2403–2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorman MF, Loizou PC, Spahr AJ, et al. , (2002). A comparison of the speech understanding provided by acoustic models of fixed-channel and channel-picking signal processors for cochlear implants. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. JSLHR, 45, 783–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorman MF, Loiselle L, Stohl J, et al. , (2014). Interaural level differences and sound source localization for bilateral cochlear implant patients. Ear. Hear, 35, 633–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu QJ, Shannon RV (1998). Effects of amplitude nonlinearity on phoneme recognition by cochlear implant users and normal-hearing listeners. J. Acoust. Soc. Am, 104, 2570–2577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner B, and Martin K (1995). “HRTF measurements of a kemar, “J. Acoust. Soc. Am, 97, 3907–3908. [Google Scholar]

- Goupell MJ, Kan A, Litovsky RY (2013a). Mapping procedures can produce non-centered auditory images in bilateral cochlear implantees. J. Acoust. Soc. Am, 133, EL101–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goupell MJ, Stoelb C, Kan A, et al. , (2013b). Effect of mismatched place-of-stimulation on the salience of binaural cues in conditions that simulate bilateral cochlear-implant listening. J. Acoust. Soc. Am, 133, 2272–2287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grantham DW, Ashmead DH, Ricketts TA, et al. , (2007). Horizontal-plane localization of noise and speech signalsby postlingually deafened adults fitted with bilateral cochlear implants. Ear Hear., 28, 524–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]