Abstract

Background and aims:

Few factors have been identified that can be used to predict response of patients with eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) to topical steroid treatment. We aimed to determine whether baseline clinical, endoscopic, histologic, and molecular features of EoE can be used to predict histologic response.

Methods:

We collected data from 97 patients with EoE, from 2009 through 2015, treated with a topical steroid for 8 weeks; 59 patients had a histologic response to treatment. Baseline clinicopathologic features and gene expression patterns were compared between patients with a histologic response to treatment (<15 eos/hpf) and non-responders (≥15 eos/hpf). We performed sensitivity analyses for alternative histologic response definitions. Multivariate logistic regression was performed to identify predictive factors associated with response to therapy, which were assessed with area under the receiver operator characteristic (AUROC) curves.

Results:

Baseline dilation was the only independent predictor of non-response (odds ratio [OR], 0.30; 95% CI, 0.10–0.89). When an alternate response (<1 eos/hpf) and non-response (<50% decrease in baseline eos/hpf) definition was used, independent predictors of response status were age (OR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.02–1.14), food allergies ( OR, 12.95; 95% CI, 2.20–76.15), baseline dilation (OR, 0.17; 95% CI, 0.03–0.88), edema or de creased vascularity (OR, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.04–1.03), and hiatal hernia (OR, 0.07; 95% CI, 0. 01–0.66). Using these 5 factors, we developed a predictive model that discriminated complete responders from non-responders with an AUROC of 0.88. Baseline gene expression patterns were not associated with treatment response and did not change with different histologic response thresholds.

Conclusions:

In an analysis of 97 patients with EoE, we found dilation to be the only baseline factor associated with non-response to steroid treatment (<15 eos/hpf). However, a model comprising five clinical, endoscopic, and histologic factors identified patients with a complete response (<1 eos/hpf). A baseline gene expression panel was not predictive of treatment response at any threshold.

Keywords: mRNA, biomarker, budesonide, fluticasone

INTRODUCTION

Topical corticosteroids are a commonly used pharmacologic therapy for the management of eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE).1, 2 Both swallowed fluticasone and budesonide have been shown to be effective in decreasing esophageal eosinophilia;3 however, symptom response has been more heterogeneous.4–7 Even in terms of histologic response, some studies have shown that nearly 50% of EoE patients may not respond to steroid therapy.8–11 Some possible reasons for non-response include patient non-compliance, inadequate treatment dosing, suboptimal steroid formulation or esophageal contact time, and a possible steroid refractory phenotype of EoE.5, 11,12 Having the ability to identify which patients are less likely to have a histologic response to steroids would have important prognostic implications.

Despite the need for better risk-stratification tools to assess treatment response in EoE, there are few data identifying predictors of topical steroid response. One retrospective study showed the need for baseline dilation and molecular factors such as decreased levels of mast cells and eotaxin-3 predicted non-response in EoE adults treated with topical fluticasone or budesonide.13 Phenotypic differences have also been implicated in predicting treatment response. Those with a fibrostenotic phenotype and narrowed esophagus are less likely to respond to topical steroids.12 Gene analysis has shown that polymorphisms in the transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) gene are associated with steroid resistance in EoE.14 Similarly, an EoE gene array comprising of 94 genes, the EoE diagnostic panel (EDP), showed a subset of genes were differentially expressed in non-responders to fluticasone.4

Identifying predictors of treatment response to topical steroids is key to delivering effective and individualized disease management, but there are inadequate prospective data assessing them, and the potential predictors noted above are not yet routinely used in clinical care. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine whether baseline (pre-treatment) clinical, endoscopic, histologic, and molecular features of EoE can be used to predict histologic response to topical steroids in adult EoE patients.

METHODS

Study design, patients, and data collection

This was an analysis of data and samples collected during a prospective study conducted at the University of North Carolina from 2009 to 2015.15 Participants were consecutive adults scheduled to undergo outpatient upper endoscopy for symptoms of esophageal dysfunction. Participants were enrolled prior to undergoing endoscopy and were excluded if they had a known diagnosis of EoE or eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorder, esophageal varices, prior esophageal surgery, bleeding or on anticoagulation, medical instability or multiple co-morbidities.

Eligible cases were diagnosed with EoE per consensus guidelines,1, 16 with at least 15 eosinophils per high-power field (eos/hpf) on esophageal biopsy after an 8-week course of high dose proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy and exclusion of alternate causes of esophageal eosinophilia. Those with PPI-responsive esophageal eosinophilia (PPI-REE) were excluded from the present analysis. This is because at the time the study was designed and conducted, failure of a PPI trial remained necessary for EoE diagnosis.1, 16, 17 Because we previously demonstrated the clinical and molecular similarities between EoE and PPI-REE,18, 19 and because the present study protocol focused on predicting steroid response, steroids were not routinely offered to PPI-REE patients. The study was approved by the UNC Institutional Review Board.

Clinical data were prospectively collected using standardized case report forms as previously outlined.15, 20, 21 Atopic and food allergy history was obtained by self-report. All endoscopic biopsies were obtained per research protocol. Two biopsies from the proximal, one from the mid, and two from the distal esophagus were collected. Gastric and duodenal biopsies were collected to exclude alternate eosinophilic disorders. From each biopsy, the maximum eosinophil count (eosinophils per high-power field [eos/hpf]) was quantified using a microscopic field size of 0.24mm2 and per our previously described method.22, 23

Topical steroid treatment and definitions of histologic response

EoE cases were treated per a standard clinical protocol with an 8-week course of either oral viscous budesonide (1mg twice a day) or fluticasone from a multi-dose inhaler (880 mcg twice a day).24 Repeat EGD with esophageal biopsies were performed at the end of the 8-week treatment, and follow-up clinical and symptom data were also collected.

The primary outcome of this study was histologic response. There is debate in the literature related to the “correct” histologic resp onse threshold In EoE25–27 varying eosinophil cutpoints have been used in different studies,24 and an arbitrary threshold may obscure response data, making it harder to differentiate predictive factors. Therefore, two separate histologic response definitions were used in this study. For the first, we defined response as <15 eos/hpf and non-response as ≥15 eos/hpf on post-treatment esophageal biopsies. For the second, response was defined as “complete” responders comprising of those with <1 eos/hpf and “complete” non- responders as those with <50% decrease in eosinophil counts from baseline following treatment, and those who did not fit these criteria were omitted. This second definition allowed us to perform a sensitivity analysis by comparing extremes of the response threshold, “complete” responders versus “complete” non-responders, to det ermine if additional predictors can be identified.

Gene expression determination

After completion of patient enrollment, gene expression determination was performed using a single RNA-later-preserved biopsy from the mid-esophagus (approximately 10 cm above the gastroesophageal junction), that had been snap frozen and stored at −80oC immediately after collection (Miraca Life Sciences, Phoenix, AZ), as previously reported.28, 29 After thawing of frozen specimens, RNA was extracted from homogenized tissue using RNeasy Mini Extraction kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). An acceptable concentration was defined as 16.5 ng/µl of RNA for a total of 500 ng. From the extracted RNA, cDNA synthesis was performed using the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) with PCR performed on ABI 9700 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The cDNA and TaqMan Universal Master Mix II, no UNG (Life Technologies) were loaded onto Taqman TLDA cards. These cards were preloaded in a 384-well format with the 94 gene EDP panel previously developed for EoE30 and two housekeeping genes (GAPDH and 18S). PCR was performed on Quant Studio 7 (Life Technologies) to determine the gene expression levels.

Gene expression levels were measured as threshold cycles (CT) with a value <30 considered acceptable. A summary score was calculated using a previously established algorithm30 by subtracting the CT value of the housekeeping gene from the CT value of each gene of interest to acquire theCT. The absolute values of the normalized gene CT values were summed for each gene in the gene expression panel.

Statistical analysis

Clinical, endoscopic, histologic features, and overall gene scores were compared between histologic responders and non-responders using Chi-square for categorical variables, and t-tests or Wilcoxon Rank-sum for continuous variables as appropriate. Expression of individual genes was compared between responders and non-responders, using an unpaired two-sided t-test and false detection rate of 0.10 to account for multiple testing. Sensitivity analyses using alternative histologic response definitions as described above were also performed.

Multivariate logistic regression was performed to assess predictors of histologic response to topical steroids. Predictive risk factors for steroid response on bivariate comparison with p <0.10 were included in the initial model, taking into account collinear and confounding variables, that was then subsequently reduced until all factors were significant at the p <0.05 level. The model was further simplified to include only the variables that were significantly contributing to the model using likelihood ratio testing. Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed and areas under the curve (AUC) were calculated to measure the discrimination of the model and goodness-of-fit testing was performed to measure the calibration of the model. Missing data were excluded from the analysis.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

There were 97 EoE cases with complete pre- and post-treatment clinical, endoscopic, and histologic data and were included in this analysis; 91 of these patients had gene expression data available. Approximately 60% of the sample were men and >90% were Caucasian; full demographic characteristics have been previously reported.28 Of this group, 85 (88%) were treated with budesonide (mean dose 2200 mcg/day) and 12 (12%) were treated with fluticasone (mean dose 1700 mcg/day).

Predictor analysis with responder definition of <15 eos/hpf vs. ≥15 eos/hpf

There were 59 (61%) histologic responders and 38 (39%) non-responders. There was no difference in baseline mean peak eosinophil counts between responders and non-responders (129 ± 113 vs. 143 ± 135; p=0.58). There were few differ ences in clinical, endoscopic, or histologic features between responders and non-responders (Table 1). Responders tended to have more atopy (82% vs. 66%; p=0.08), less esophageal edema (46% vs. 66%; p=0.05), and less epithelial spongiosis (80% vs. 95%; p=0.05). Presence of baseline stricture (45% vs. 17%; p<0.01) and the need for esophageal dilation (47% vs. 20%; p<0.01) at baseline was significantly more common in non-responders compared to responders. In multivariate analysis, the need for baseline dilation was the only independent predictor of histologic non-response (adjusted OR=0.30, 95% CI: 0.10– 0.89).

Table 1:

Characteristics of Non-Responders (≥15 eos/hpf) and Responders (<15 eos/hpf) after Topical Steroid Therapy

| Non-responders (≥15 eos/hpf) (n = 38) |

Responders (<15 eos/hpf) (n = 59) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean yrs ± SD) | 35.0 ± 12.9 | 39.6 ± 13.0 | 0.87 |

| Male (n, %) | 23 (61) | 35 (59) | 0.91 |

| White (n, %) | 35 (92) | 57 (97) | 0.33 |

| Any atopy (n, %) | 23 (66) | 45 (82) | 0.08 |

| Baseline endoscopic findings (n, %) | |||

| Rings | 32 (84) | 49 (83) | 0.88 |

| Stricture | 17 (45) | 10 (17) | <0.01 |

| Narrowing | 16 (42) | 16 (27) | 0.13 |

| Furrows | 36 (95) | 50 (85) | 0.13 |

| Exudates/white plaques | 20 (53) | 30 (51) | 0.86 |

| Edema/decreased vascularity | 25 (66) | 27 (46) | 0.05 |

| Hiatal hernia | 7 (18) | 5 (8) | 0.15 |

| Dilation | 18 (47) | 12 (20) | <0.01 |

|

Baseline peak eosinophil counts (mean eos/hpf ± SD) |

143.3 ± 135.2 | 129.1 ± 113.1 | 0.58 |

| Baseline histologic features (n, %)* | |||

| Degranulation | 37 (100) | 50 (93) | 0.09 |

| Microabscesses | 26 (70) | 35 (65) | 0.59 |

| Basal zone hyperplasia | 18 (49) | 24 (45) | 0.75 |

| Spongiosis | 35 (95) | 45 (80) | 0.05 |

| Lamina propria fibrosis | 9 (36) | 12 (34) | 0.89 |

| Treatments | |||

| Mean budesonide dose (mcg ± SD) | 2300 ± 850 | 2100 ± 650 | 0.19 |

| Mean fluticasone dose (mcg ± SD) | 1760 ± 0 | 1690 ± 310 | 0.71 |

|

Post-treatment eosinophil counts (mean eos/hpf ± SD) |

114.0 ± 88.6 | 2.2 ± 3.7 | <0.01 |

Other histologic data available for n=60 of total sample; lamina propria fibrosis (n=39). Missing data was excluded from analysis.

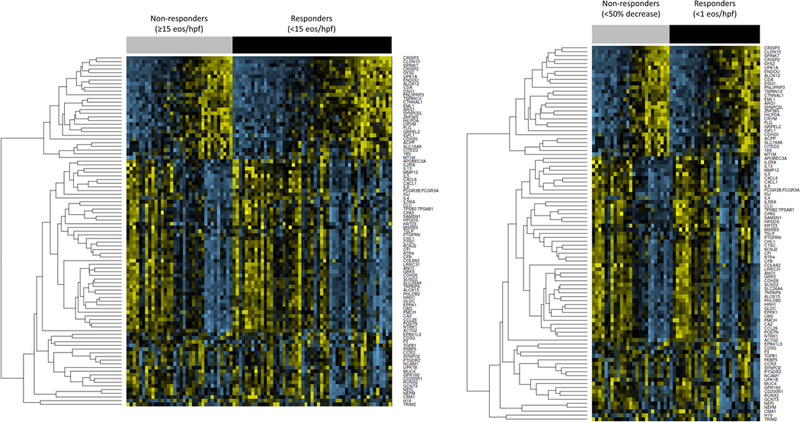

In the molecular analysis, there was no difference in mean baseline gene scores between responders and non-responders (203 ± 136 vs 185 ± 1 43; p=0.56). There was also no difference in baseline gene expression patterns (Figure 1A) or in expression of individual genes (Supplemental Table 1).

Figure 1:

Gene expression in treatment responder groups. Yellow indicates higher relative expression and blue indicates lower relative expression. Gene names are listed on the right side of the figure. (A) Non-responders defined as ≥15 eos/hpf (gray bar), and responders defined as <15 eos/hpf (black bar). (B) Non-responders, defined by <50% decrease in baseline eos/hpf (gray bar) and responders defined as <1 eos/hpf (black bar).

Predictor analysis for complete responders (<1 eos/hpf) and non-responders (<50% decrease eos/hpf)

Of 63 EoE cases who met this definition, there were 34 (54%) responders and 29 (46%) non-responders. 85% (n=29) of the responders and 93% (n=27) of the non-responders were treated with budesonide. Mean steroid doses between the responders and non-responders were similar: Budesonide (2000 mcg vs. 2340, p=0.05) and fluticasone (1630 vs. 1760 mcg; p=0.71). (Table 2). Responders were older (44 vs. 34 years, p<0.01) and had more food allergies (50% vs. 19%, p=0.02). Presence of baseline stricture (48% vs. 15%, p<0.01), narrowing (45% vs. 21%, p=0.04), need for baseline dilation (52% vs. 24%, p=0.02), and hiatal hernia (21% vs. 6%, p=0.08) were all more common in non-responders.

Table 2:

Characteristics of Non-Responders (<50% decrease in baseline eos/hpf) and Responders (<1 eos/hpf) after Topical Steroid Therapy

| Non-responders (<50% decrease eos/hpf) n = 29 |

Responders (<1 eos/hpf) n = 34 |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean yrs ± SD) | 34 ± 14 | 44 ± 13 | <0.01 |

| Male (n, %) | 16 (55) | 21 (62) | 0.60 |

| White (n, %) | 26 (90) | 32 (94) | 0.51 |

| Baseline endoscopic findings (n, %) | |||

| Rings | 24 (83) | 28 (83) | 0.97 |

| Stricture | 14 (48) | 5 (15) | <0.01 |

| Narrowing | 13 (45) | 7 (21) | 0.04 |

| Furrows | 28 (97) | 28 (82) | 0.07 |

| Exudates/white plaques | 15 (52) | 17 (50) | 0.89 |

| Edema/decreased vascularity | 17 (59) | 13 (38) | 0.11 |

| Hiatal hernia | 6 (21) | 2 (6) | 0.08 |

| Dilation | 15 (52) | 8 (24) | 0.02 |

| Baseline histologic features (n, %)* | |||

| Degranulation | 28 (100) | 31 (97) | 0.35 |

| Microabscesses | 17 (61) | 21 (66) | 0.69 |

| Basal zone hyperplasia | 11 (39) | 14 (45) | 0.65 |

| Spongiosis | 27 (96) | 26 (79) | 0.04 |

| Lamina propria fibrosis | 8 (40) | 6 (32) | 0.58 |

|

Baseline peak eosinophil counts (mean eos/hpf ± SD) |

108 ± 106 | 124 ± 115 | 0.56 |

| Treatments | |||

| Mean budesonide dose (mcg ± SD) | 2340 ± 900 | 2000 ± 0 | 0.05 |

| Mean fluticasone dose (mcg ± SD) | 1760 ± 0 | 1630 ± 430 | |

|

Post-treatment eosinophil counts (mean eos/hpf ± SD) |

131 ± 82 | 0 ± 0 | <0.01 |

Other histologic data available for n=60 of total sample; lamina propria fibrosis (n=39). Missing data was excluded from analysis.

In multivariable logistic regression, older age and having food allergies independently predicted increased odds of complete response, while baseline dilation, presence of edema/decreased vascularity on endoscopy, and presence of hiatal hernia on endoscopy, independently predicted decreased odds of complete response (Table 3). Using these 5 factors, a predictive model had sensitivity of 85%, specificity of 78%, and accuracy of 82% in discriminating complete responders from clear non-responders. ROC curve analysis showed an AUC of 0.88, and the chi-square test of goodness-of-fit had p=0.90, indicating a good fit (Figure 2).

Table 3:

Predictors of Complete Response (<1 eos/hpf) to Topical Steroid Therapy

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 1.08 (1.02, 1.14) |

| Food allergies | 12.95 (2.20, 76.15) |

| Hiatal hernia | 0.07 (0.01, 0.66) |

| Baseline dilation | 0.17 (0.03, 0.88) |

| Edema/decreased vascularity | 0.20 (0.04, 1.03) |

OR >1.0 indicates increased odds of complete response to steroids

Figure 2:

Receiver operator characteristic curve (ROC) for a multivariable predictive model of complete histologic response (defined at <1 eos/hpf).The area under the curve (AUC) is reported.

In the molecular analysis, there was no difference in mean baseline gene scores between responders and non-responders (192 ± 137 vs 196 ± 1 51; p=0.92). There was also no difference in baseline gene expression patterns (Figure 1B) or in expression of individual genes from a limited gene expression panel (Supplemental Table 1).

DISCUSSION

In this prospective study of EoE cases treated with an 8-week course of a topical steroid, 46–61% had histologic response based on the definition used. When a more traditional response (<15 eos/hpf) and non-response (≥15 eos/hpf) definition was applied,26, 27 other than the need for baseline dilation, there were no pre-treatment features that independently predicted response to steroid therapy. When alternate response (<1 eos/hpf) and non-response (<50% decrease in baseline eos/hpf) definitions were used, independent predictors of response were older age and history of food allergies, and predictors of non-response were presence of edema or hiatal hernia endoscopically, and the need for baseline dilation. This model showed good discrimination (AUC = 0.88) between complete steroid responders and the clear non-responders. However, no differences in baseline gene expression, either measured by the summary gene score or by differential expression between individual genes, were noted between the groups regardless of the response definition.

Non-responders were found to have a significantly higher prevalence of baseline strictures and esophageal narrowing. Since the presence of strictures and narrowing were highly correlated with the need for baseline dilation, dilation was used as a surrogate marker for those with a severe fibrostenotic phenotype and was included in the multivariable model. Need for baseline dilation was a common predictor identified using either one of the treatment response definitions. Dilation was previously found to be a predictor of non-response in a retrospective cohort of EoE patients from our center13 and in preliminary data from a separate study.31 A steroid resistant phenotype of EoE, an extreme narrow-caliber esophagus, has also been described.12 In the context of these studies that show that the need for dilation is associated with a decreased likelihood of response to topical steroids, it is unclear whether swallowed fluticasone or oral viscous budesonide do not provide effective drug delivery in those with strictures or if fibrostenotic disease represents a more severe disease state that is treatment refractory.

Data supporting the theory of steroid resistance as a mechanism for non-response include differential gene expression signatures4 and a single nucleotide polymorphism in TGF-β1.14 Additionally, increased levels of esophageal FK506-binding protein 5 (FKBP5) mRNA levels have been noted in patients treated with fluticasone, indicating that swallowed steroid therapies can directly affect gene expression in EoE and can potentially prognosticate treatment response.32 Unfortunately, in this study, we did not find differences in gene expression profiles between the responders and non-responders, and specifically did not see any difference in the previously reported gene signature, or in TGF-β or FKBP5 expression levels.4, 14, 32 However, we did not perform patient genotyping or SNP testing. In our study, history of food allergies was associated with increased odds of complete response (<1eos/hpf). Two prior studies support this finding and showed increased levels of mast cells in esophageal tissue in steroid responsive patients.13, 33 However, other studies have shown partial or complete non-response to steroids in those with history of allergies.34, 35 Finally, there are also studies that have failed to identify any predictors of response.36, 37

Why might the search for predictors of response be so difficult? One reason could be in the choice of treatment response definition. Since the EoE diagnosis definition is ≥15 eos/hpf, some studies define treatment response as <15 eos/hpf and non-response as ≥15 eos/hpf, and this is now supported by analyses showing symptom and endoscopic improvements at this threshold.26, 27 However, with this definition, a patient who has a decrease in eosinophil count from a baseline of 100 eos/hpf to 15 eos/hpf after treatment is considered a non-responder despite having an 85% decrease in the eosinophil counts. This raises the question of whether there is value in assessing treatment response as a proportional change from baseline eosinophil count, rather than as a discrete cut-point. Therefore, in this study, we tested an alternate treatment response definition to compare the extremes on the response spectrum, which resulted in identification of a larger set of clinical predictors, but did not change the results of the molecular analysis. However, the primary limitation of the model derived from this approach is that it cannot be applied to the group of intermediate responders. Other study limitations include lack of formal allergy testing and having a standardized protocol for steroid administration, which is more reflective of a real-world practice. A final limitation is the focus on histologic response. We acknowledge that symptom, endoscopic, and other important endpoints need to be assessed, and are a focus of future research. However, at the time this study was designed and conducted, these metrics were either not in existence or did not have clearly defined response thresholds.

Despite these limitations, the study has multiple strengths. This was a large prospective cohort utilizing a rigorous study design, data collection protocols, and sample handling. In addition, we tested multiple treatment response definitions to demonstrate differences in results, and we were able to incorporate molecular analyses. The findings of this study support additional data linking severe fibrostenotic disease with steroid resistance.

In conclusion, we showed that baseline dilation was the only predictor of response to topical steroid treatment at a histologic response threshold of <15 eos/hpf. No other clinical or molecular features of EoE predicted response at this level. However, a model comprised of five factors was able to predict complete response (<1 eos/hpf) with AUC of 0.88 compared to the EoE group with clear non-response (<50% decrease in baseline eos/hpf), which, if validated, suggests a high degree of clinical utility. Patients who are at high risk for non-response to topical steroids could be identified early so that alternative therapies or delivery formulations can be used.38 There may also be a need to assess response using more nuanced definitions due to the limitations of using distinct eosinophil cutpoints, and should be taken into account in future studies aimed at identifying predictors of histologic response.

Supplementary Material

WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW

Background:

Few baseline clinical, endoscopic, histologic, and molecular predictors of histologic response to topical steroids have been identified in eosinophilic esophagitis. Knowledge of independent predictors of treatment response would help target clinical care.

Findings:

A model comprising of five factors predicted complete response (<1eos/hpf) with AUC of 0.88 compared to those with clear non-response (<50% decrease in baseline eos/hpf), with no differences in a gene expression panel measured at baseline.

Implications for patient care:

Patients at high risk for non-response to topical steroids could be identified early so that alternative therapies can be used.

Acknowledgments

Grant support:

Supported by T32DK007634 (SE), K23DK090073 (ESD) and K24DK100548 (NJS).

Abbreviations:

- AUC

area under the curve

- CT

threshold cycles

- EDP

EoE diagnostic panel

- EoE

eosinophilic esophagitis

- eos/hpf

eosinophils per high-power field

- FKBP5

FK506-binding protein

- OR

odds ratio

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PPI-REE

PPI-responsive esophageal eosinophilia

- ROC

receiver operating curve

- TGF-β1

transforming growth factor β1

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures:

ESD has received research funding from Adare, Meritage, Miraca, Nutricia, Celgene/Receptos, Regeneron, and Shire; has consulted for Adare, Alivio, Allakos, AstraZeneca, Banner, Enumeral, Celgene/Receptos, GSK, Regeneron, Robarts, and Shire; and has received educational grants from Banner and Holoclara. The author authors report no potential related competing interests.

Specific author contributions (all authors approved the final draft submitted):

Eluri - Study design, data interpretation, manuscript drafting, critical revision Selitsky – Data acquisition, data interpretation, c ritical revision Perjar, Hollyfield, Betancourt, Randall, Rusin – Da ta acquisition, critical revision Woosley - Study design, data interpretation, critical revision Shaheen – Project conception, study design, data in terpretation, critical revision Dellon – Project conception, study design, data int erpretation, manuscript drafting, critical revision

REFERENCES

- 1.Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Hirano I, et al. ACG clinical guideline: Evidenced based approach to the diagnosis and management of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108(5):679–92; quiz 93. Epub 2013/04/10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peery AF, Shaheen NJ, Dellon ES. Practice patterns for the evaluation and treatment of eosinophilic oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010;32(11–12):1373–82. Epub 2010/11/06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cotton CC, Eluri S, Wolf WA, et al. Six-Food Elimination Diet and Topical Steroids are Effective for Eosinophilic Esophagitis: A Meta-Regression. Dig Dis Sci 2017. Epub 2017/06/14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Butz BK, Wen T, Gleich GJ, et al. Efficacy, dose reduction, and resistance to high-dose fluticasone in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2014;147(2):324–33.e5. Epub 2014/04/29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dellon ES, Sheikh A, Speck O, et al. Viscous topical is more effective than nebulized steroid therapy for patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2012;143(2):321–4. e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alexander JA, Jung KW, Arora AS, et al. Swallowed fluticasone improves histologic but not symptomatic response of adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;10(7):742–9.e1. Epub 2012/04/06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miehlke S, Hruz P, Vieth M, et al. A randomised, double-blind trial comparing budesonide formulations and dosages for short-term treatment of eosinophilic oesophagitis. Gut 2016;65(3):390–9. Epub 2015/03/21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Francis DL, Foxx-Orenstein A, Arora AS, et al. Results of ambulatory pH monitoring do not reliably predict response to therapy in patients with eosinophilic oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2012;35(2):300–7. Epub 2011/11/25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Konikoff MR, Noel RJ, Blanchard C, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of fluticasone propionate for pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2006;131(5):1381–91. Epub 2006/11/15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schaefer ET, Fitzgerald JF, Molleston JP, et al. Comparison of oral prednisone and topical fluticasone in the treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis: a randomized trial in children. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;6(2):165–73. Epub 2008/02/02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dellon ES. Management of refractory eosinophilic oesophagitis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;14(8):479–90. Epub 2017/05/26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eluri S, Runge TM, Cotton CC, et al. The extremely narrow-caliber esophagus is a treatment-resistant subphenotype of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc 2016;83(6):1142–8. Epub 2015/11/27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolf WA, Cotton CC, Green DJ, et al. Predictors of response to steroid therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis and treatment of steroid-refractory patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13(3):452–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aceves SS, Newbury RO, Chen D, et al. Resolution of remodeling in eosinophilic esophagitis correlates with epithelial response to topical corticosteroids. Allergy 2010;65(1):109–16. Epub 2009/10/03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dellon ES, Rusin S, Gebhart JH, et al. A Clinical Prediction Tool Identifies Cases of Eosinophilic Esophagitis Without Endoscopic Biopsy: A Prospective Study. Am J Gastroenterol 2015;110(9):1347–54. Epub 2015/08/26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011;128(1):3–20.e6; quiz 1-Epub 2011/04/12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Molina-Infante J, Bredenoord AJ, Cheng E, et al. Proton pump inhibitor-responsive oesophageal eosinophilia: an entity challenging current diagnostic criteria for eosinophilic oesophagitis. Gut 2016;65(3):524–31. Epub 2015/12/20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dellon ES, Speck O, Woodward K, et al. Clinical and endoscopic characteristics do not reliably differentiate PPI-responsive esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis in patients undergoing upper endoscopy: a prospective cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108(12):1854–60. Epub 2013/10/23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wen T, Dellon ES, Moawad FJ, et al. Transcriptome analysis of proton pump inhibitor-responsive esophageal eosinophilia reveals proton pump inhibitor-reversible allergic inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;135(1):187–97.e4. Epub 2014/12/03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dellon ES, Rusin S, Gebhart JH, et al. Utility of a Noninvasive Serum Biomarker Panel for Diagnosis and Monitoring of Eosinophilic Esophagitis: A Prospective Study. Am J Gastroenterol 2015;110(6):821–7. Epub 2015/03/18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koutlas NT, Eluri S, Rusin S, et al. Impact of smoking, alcohol consumption, and NSAID use on risk for and phenotypes of eosinophilic esophagitis. Dis Esophagus 2018;31(1):1–7. Epub 2017/10/13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dellon ES, Fritchie KJ, Rubinas TC, et al. Inter- and intraobserver reliability and validation of a new method for determination of eosinophil counts in patients with esophageal eosinophilia. Dig Dis Sci 2010;55(7):1940–9. Epub 2009/10/16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rusin S, Covey S, Perjar I, et al. Determination of esophageal eosinophil counts and other histologic features of eosinophilic esophagitis by pathology trainees is highly accurate. Hum Pathol 2017;62:50–5. Epub 2017/01/04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dellon ES, Liacouras CA. Advances in Clinical Management of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2014;147(6):1238–54. Epub 2014/08/12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirano I Therapeutic end points in eosinophilic esophagitis: is elimination of esophageal eosinophils enough? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;10(7):750–2. Epub 2012/03/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reed CC, Wolf WA, Cotton CC, et al. Optimal Histologic Cutpoints for Treatment Response in Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Analysis of Data From a Prospective Cohort Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;16(2):226–33.e2. Epub 2017/10/11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolf WA, Cotton CC, Green DJ, et al. Evaluation of Histologic Cutpoints for Treatment Response in Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology research 2015;4(10):1780–7. Epub 2016/04/26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dellon ES, Veerappan R, Selitsky SR, et al. A Gene Expression Panel is Accurate for Diagnosis and Monitoring Treatment of Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Adults. Clinical and translational gastroenterology 2017;8(2):e74 Epub 2017/02/10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dellon ES, Yellore V, Andreatta M, et al. A single biopsy is valid for genetic diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis regardless of tissue preservation or location in the esophagus. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2015;24(2):151–7. Epub 2015/06/27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wen T, Stucke EM, Grotjan TM, et al. Molecular diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis by gene expression profiling. Gastroenterology 2013;145(6):1289–99. Epub 2013/08/28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moawad F, Albert D, Heifert T, et al. Predictors of Non-Response to Topical Steroids Treatment in Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108: S14-S.

- 32.Caldwell JM, Blanchard C, Collins MH, et al. Glucocorticoid-regulated genes in eosinophilic esophagitis: a role for FKBP51. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;125(4):879–88.e8. Epub 2010/04/08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boldorini R, Mercalli F, Oderda G. Eosinophilic oesophagitis in children: responders and non-responders to swallowed fluticasone. J Clin Pathol 2013;66(5):399–402. Epub 2013/02/09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Noel RJ, Putnam PE, Collins MH, et al. Clinical and immunopathologic effects of swallowed fluticasone for eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004;2(7):568–Epub 2004/06/30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pesek RD, Rettiganti M, O’Brien E, et al. Effects of allergen sensitization on response to therapy in children with eosinophilic esophagitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2017;119(2):177–83. Epub 2017/07/06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Straumann A, Conus S, Degen L, et al. Budesonide is effective in adolescent and adult patients with active eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2010;139(5):1526–37, 37 e1. Epub 2010/08/05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Albert D, Heifert TA, Min SB, et al. Comparisons of Fluticasone to Budesonide in the Treatment of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci 2016;61(7):1996–2001. Epub 2016/04/21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miehlke S, Hruz P, von Arnim U, et al. Two New Budesonide Formulations Are Highly Efficient for Treatment of Active Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Results From a Randomized, Double-Blind, Double-Dummy, Placebo-Controlled Multicenter Trial. Gastroenterology 2014;146(5):S16–S. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.