Abstract

Background & Aims:

The nuclear receptor subfamily 0 group B member 2 (NR0B2, also called SHP) is expressed at high levels in liver and intestine. Postprandial fibroblast growth factor 19 (human FGF19, mouse FGF15) signaling increases the transcriptional activity of SHP. We studied the functions of SHP and FGF19 in intestines of mice, including their regulation of expression of the cholesterol transporter NPC1-like intracellular cholesterol transporter 1 (NPC1L1) and cholesterol absorption.

Methods:

We performed histologic and biochemical analyses of intestinal tissues from C57BL/6 and SHP-knockout mice and performed RNA-seq analyses to identify genes regulated by SHP. The effects of fasting and refeeding on intestinal expression of NPC1L1 was examined in C57BL/6, SHP-knockout, and FGF15-knockout mice. Mice were given FGF19 daily for 1 week; fractional cholesterol absorption, cholesterol and bile acid (BA) levels, and composition of BAs were measured. Intestinal organoids were generated from C57BL/6 and SHP-knockout mice and cholesterol uptake was measured. Luciferase reporter assays were performed with HT29 cells.

Results:

We genes that regulate lipid and ion transport in intestine, including NPC1L1, to be upregulated and cholesterol absorption was increased in SHP-knockout mice compared with C57BL/6 mice. Expression of NPC1L1 was reduced in C57BL/6 mice following refeeding after fasting, but not in SHP-knockout or FGF15-knockout mice. SHP-knockout mice had altered BA composition compared with C57BL/6 mice. FGF19 injection reduced expression of NPC1L1, decreased cholesterol absorption, and increased levels of hydrophilic BAs, including tauro-alpha- and -beta-muricholic acids; these changes were not observed in SHP-knockout mice. Sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor 2 (SREBF2), which regulates cholesterol, activated transcription of NPC1L1. FGF19 signaling led to phosphorylation of SHP, which inhibited SREBF2 activity.

Conclusions:

Postprandial FGF19 and SHP inhibit SREBF2, which leads to repression of intestinal NPC1L1 expression and cholesterol absorption. Strategies to increase FGF19 signaling to activate SHP might be developed for treatment of hypercholesterolemia.

Keywords: FGF15, FXR, bile acids, SREBF2

Introduction

The liver and the intestine have important roles in regulating cholesterol levels. The liver is a major site for sterol biosynthesis and production, uptake of lipoproteins, and metabolism of cholesterol to bile acids (BAs)1–4. The intestine also maintains whole body cholesterol levels by mediating intestinal absorption of dietary and biliary cholesterol and also by direct trans-intestinal cholesterol excretion (TICE)1, 5–8. These processes are regulated by interactions between the liver and intestine. In response to a meal, the BA-activated nuclear receptor, farnesoid X receptor (FXR, NR1H4), induces expression of intestinal fibroblast growth factor 19 (human FGF19, mouse FGF15), which acts at the liver and regulates expression of target genes important for cholesterol and BA metabolism, including nuclear receptor subfamily 0 group B member 2 (NR0B2, also known as small heterodimer partner, SHP)9–12.

SHP is an unusual nuclear receptor that does not have a DNA binding domain but acts as a co-repressor for numerous transcriptional factors, including LRH-1, SREBF2 (also known as SREBP-2) and AhR10, 13, 14. SHP mediates epigenomic repression of genes by recruiting repressive histone modifying proteins11, 15, 16. As an orphan nuclear receptor, endogenous ligands of SHP are unknown, but its nuclear localization and gene-repressive function are enhanced by post-translational modifications in response to postprandial FGF15/19 signaling10, 14, 17, 18. SHP is well-known to repress hepatic BA production9, 11, 18, 19, but is also involved in hepatic lipid metabolism, inflammation, and circadian regulation of metabolism13, 20–22. Recent genomic and follow-up studies of mice treated with FGF19 revealed new hepatic functions of SHP and FGF19 in inhibition of sterol biosynthesis, one-carbon metabolism, and autophagy10, 14, 23. SHP and FGF19 repress both cholesterol conversion into BA and sterol biosynthesis in the liver9–11, but intestinal functions of the FGF19-SHP axis in cholesterol regulation have not been reported.

NPC1-like intracellular cholesterol transporter (NPC1L1) is the rate-limiting transmembrane transporter for cholesterol absorption from the intestinal lumen and mediates absorption of both dietary and biliary cholesterol3, 7, 8. NPC1L1 is the target of the cholesterol-lowering drug, ezetimibe, which suppresses intestinal cholesterol absorption and promotes TICE6, 7, 24. Despite its importance as a therapeutic target, physiological regulation of intestinal Npc1l1 gene expression during feeding and fasting cycles is poorly understood.

In this study, we have identified a previously unknown intestinal function of SHP and postprandial FGF19 signaling in the inhibition of NPC1L1 expression and fractional cholesterol absorption. In mechanistic studies, we show that SREBF2, a key transcriptional regulator of cholesterol, induces expression of NPC1L1 early after feeding and that SHP inhibits the SREBF2-mediated transactivation of Npc1l1 in response to postprandial FGF19 signaling, which contributes to decreased cholesterol absorption in the late fed-state.

Materials and Methods

Animal experiments.

Male C57BL/6, SHP-knockout, and FGF15-knockout mice (8–12 weeks old) were fasted for 12 h and then, refed with normal chow (Teklad, #8664) for 1, 2, 4 or 6 h as indicated in the figure legends. Since SHP is expressed throughout the small intestine and NPC1L1 is expressed more abundantly in the jejunum and ileum of mouse intestine (Supplementary Figure 1) as previously reported25, the jejunum and ileum were collected for further studies. For FGF19 experiments, we used human FGF19 since mouse FGF15 is less stable. While FGF19 and Fgf15 have some differences in action26, in general, both FGF15 and FGF19 have the similar metabolic effects and have been utilized in previous studies9, 10, 12, 14, 18, 27. WT and SHP-knockout mice were fasted for 12 h and injected via the tail vein with vehicle or FGF19 (1 mg/kg), and 2 h or 6 h later, tissues were collected. For determining the effect of FGF19 treatment on metabolic outcomes, such as BA composition, fractional cholesterol absorption, and cholesterol levels, mice were injected daily with vehicle or FGF19 for 1 week as described28 and then caged individually, fasted overnight, and refed for 24 h. [14C]cholesterol and [3H]sitosterol were administered by gavage and 1 mg/kg FGF19 or vehicle was injected i.v. All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use and Biosafety Committees of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

RNA-seq analysis.

WT and SHP-knockout mice were fed for 6 h after fasting overnight. Intestinal RNA from the jejunum and ileum parts was isolated with the RNeasy Kit (Qiagen) and the cDNA library was sequenced using an Illumina HiSeq2000 (Illumina, San Diego, CA) to produce paired-end 100 bp reads. Trimmomatic (v0.38) was used to remove sequence adapters, quality control was checked by FastQC (v0.11.5), and sequencing alignment was performed by STAR (v2.6.0c). The differential expression profiles of RNA-seq were analyzed by the edgeR-based R (v3.5.0) pipeline and results were presented by volcano plot. For all comparisons, p < 0.01 were considered significant. Gene ontology was analyzed by the DAVID program (v6.7). For validation, mRNA levels, normalized to 36B4, were quantified by RT-qPCR. Primer sequences are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Chromatin IP (ChIP).

Mouse intestine tissues were minced, washed twice with PBS, and incubated with 1% (w/v) formaldehyde for 10 min and then with 125 mM glycine for 5 min. Chromatin samples were sonicated for 30 min using a QSonica 800R2–110 at amplitude setting 70% with sonication pulse rate 15 s on and 45 s off. Chromatin was incubated with 2 µg antibody or control IgG overnight at 4°C and then with a Protein G–Sepharose slurry (GE Healthcare) containing salmon-sperm DNA for 1 h. The slurry was washed three times with 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, containing successively 150 mM NaCl, 500 mM NaCl, and 0.25 M LiCl, and then incubated overnight at 65°C to reverse the crosslinking. For re-ChIP, immunoprecipitated chromatin was eluted by incubation with 10 mM DTT for 30 min at 37°C, the eluate was d iluted 20-fold and re-precipitated, and crosslinks were reversed. DNA was isolated and quantified by qPCR. Primer sets used are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Histological analysis.

Mouse jejunum was embedded in paraffin for immunohistochemistry. As previously described10, 14, 18, T55-phospho SHP and NPC1L1 in paraffin sections were detected using the HRP/DAB kit (Abcam, #Ab64261), and nuclei were stained with hematoxylin. The stained samples were imaged with a NanoZoomer (Hamamatsu).

Fractional cholesterol absorption assay.

Fractional cholesterol absorption was determined by the fecal dual isotope method as previously described29. Briefly, 100 µl of corn oil containing [14C]cholesterol (0.5 µCi), [3H]sitosterol (1 µCi), and 0.1 mg unlabeled cholesterol was administered by gavage to WT and SHP-knockout mice. After 24 h, radioactivity in the feces was determined by liquid scintillation counting and was subtracted from the amount administered to calculate the amount absorbed.

Measurement of cholesterol levels.

Fecal cholesterol was extracted with chloroform:methanol (2:1) and dissolved in PBS containing 1% Triton X-100 after evaporation as described30. Fecal, serum, and lipoprotein cholesterol levels were measured using a HDL and LDL/VLDL quantitation kit (MAK045–1KT, Sigma). For colorimetric assays, the levels were measured by the absorbance at 570 nm using SpectraMax M2 Microplate Reader (Molecular Device).

Mouse intestinal organoids.

Diced (2 mm pieces) jejunum and ileum from WT and SHP-knockout mice were incubated in Gentle Cell Dissociation Reagent (STEMCELL Technologies Inc) and cells were filtered through a cell strainer (70 µm pore). The crypts were suspended in the IntestiCult™ Organoid Growth Medium (STEMCELL Technologies Inc) with 50% Matrigel and incubated for 10 min at 37°C. The Matrigel embedded-cells were maintained for 10 days.

Cholesterol uptake.

Cholesterol uptake was determined in intestinal organoids or HT29 cells using a commercial kit (600440, Cayman Chemical). Organoids or HT29 cells were cultured in 96-well plates in IntestiCult™ Organoid Growth Medium or DMEM serum free media, respectively, containing 20 µg/ml of fluorescently-tagged cholesterol. After treatment with 50 ng/ml FGF19 for 24 h, cells were washed with PBS and the fluorescence intensity was measured with excitation at 485 nm and emission at 535 nm using a Microplate Reader (Molecular Device).

DNA motif analysis.

Transcription factor binding motifs within SHP binding regions in the Npc1l1 promoter were identified using the JASPAR database.

Co-IP analysis.

Extracts of mouse intestine were incubated with 2 µg of antibodies for SREBF2 or SHP or control IgG for 30 min, and 35 µl of 25% protein G Sepharose was added for 2 h, Sepharose beads were washed, and bound proteins were detected by IB.

Luciferase reporter assays.

A DNA fragment containing the region from −721 to −966 of the Npc1l1 promoter was inserted into the pGL3-luc plasmid. HT29 cells were transfected with reporter plasmids (50–200 ng), expression plasmids for β-galactosidase (100 ng), SREBF2 (50 ng) or SHP (5–50 ng). Luciferase activities were normalized to β-galactosidase activities.

Statistical analysis.

GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad software) was used for data analysis. Statistical significance was determined by the Student’s two-tailed t-test or one- or two-way ANOVA with the False Discovery Rate (FDR) post-test for single or multiple comparisons as appropriate. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

SHP regulates intestinal genes involved in cholesterol regulation.

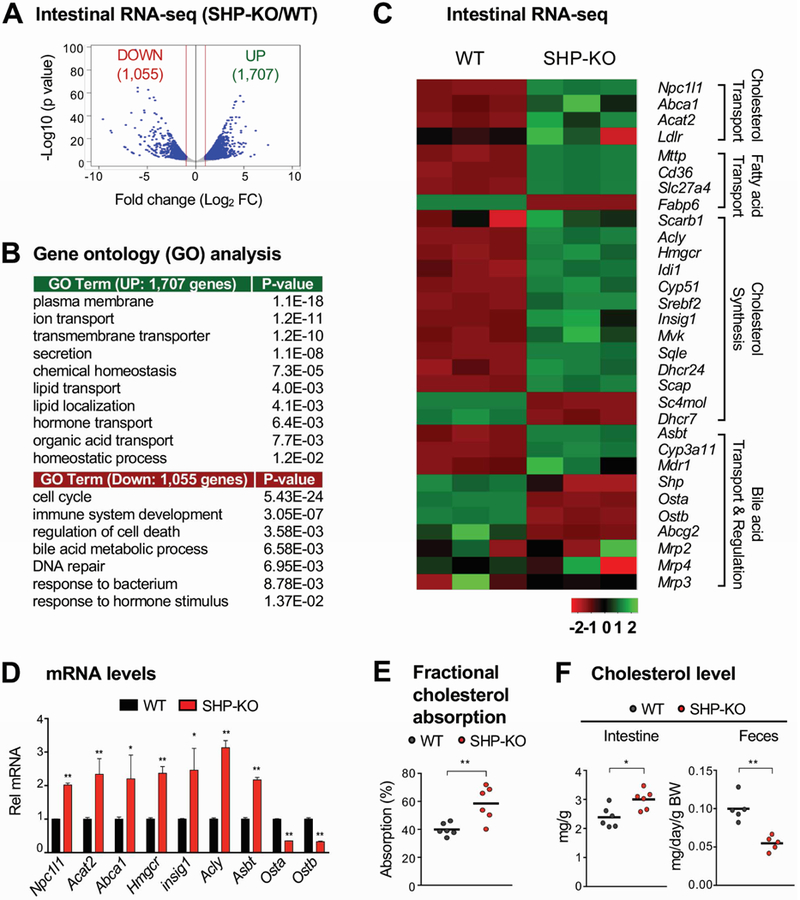

Global regulation by SHP of intestinal gene expression in wild type (WT) C57BL/6 and SHP-knockout mice was analyzed by RNA-seq. Since the gene-regulatory function of SHP is increased in the late fed-state10, 11, 14, 18, mice were refed for 6 h after fasting overnight. In SHP-knockout compared to WT mice, 1,707 genes were upregulated, and 1,055 genes downregulated by 2-fold or more (Figure 1A). In gene ontology analysis, genes upregulated included those involved in transmembrane transporter and ion/lipid transport; whereas genes downregulated were involved in the cell cycle, the immune response, and apoptosis (Figure 1B). Remarkably, expression of genes important for cholesterol transport, including Npc1l17, sterol biosynthetic genes, including Hmgcr, and key BA transporters, Ost α/β and Asbt3, was altered in SHP-knockout mice (Figure 1C). Changes in mRNA levels of selected genes, including Npc1l1, were confirmed (Figure 1D). Consistent with increased expression of Npc1l1, fractional cholesterol absorption was significantly increased (Figure 1E), intestinal cholesterol levels increased, and fecal cholesterol levels decreased (Figure 1F) in SHP-knockout compared to WT mice. These results suggest that SHP functions in the repression of intestinal cholesterol absorption.

Figure 1. Intestinal RNA-seq analysis in WT and SHP-knockout mice.

(A-C) WT (C57BL/6) and SHP-knockout (KO) mice were fed normal chow for 6 h after fasting overnight. Total RNA was isolated from the jejunum and ileum and analyzed by RNA-seq (n=3 mice). (A) Genome-wide changes in mRNA expression shown in a volcano plot. The numbers refer to the number of genes up- or down-regulated by 2-fold or more with a p-value < 0.01. (B) Gene ontology analysis of biological pathways using DAVID Tools (v 6.7). (C) Heatmap of the differential expression in three WT or SHP-knockout mice of selected genes in the functional categories indicated at the right. Normalized log2-counts-per-million (logCPM) gene counts are centered and z-scaled. (D) Levels of the mRNAs of the indicated genes were measured by RT-qPCR. (E-F) WT and SHP-knockout mice were individually caged, fasted overnight, and refed normal chow for 24 h. (E) [14C]cholesterol and [3H]sitosterol were administered by gavage at the time of refeeding. After 24 h, feces were collected and radioactivity in the feces was determined by scintillation counting and percent absorption was calculated as described in Methods. (F) Feces were collected 24 h after refeeding and cholesterol levels in the intestine and feces were measured and normalized to intestine weight or body weight, respectively. (D, E, F) Statistical significance was determined by the Student’s t-test, (SEM, n=3 to 6, *P <0.05, **P <0.01).

Intestinal NPC1L1 expression is highly elevated in SHP-knockout mice.

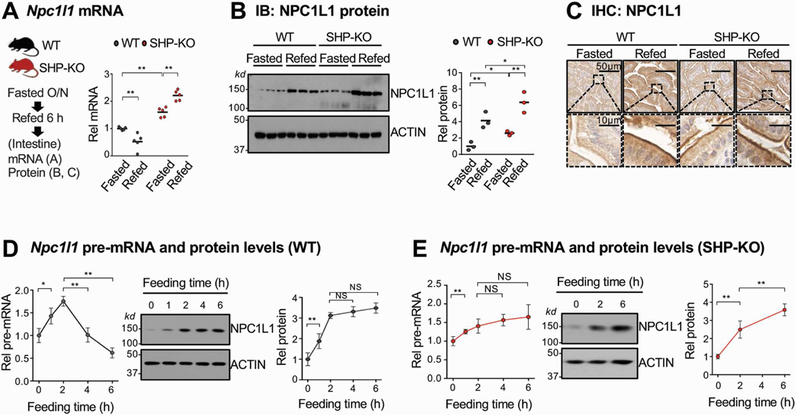

NPC1L1 plays a key role in postprandial intestinal absorption of both dietary and biliary cholesterol7, 12. To test whether expression of NPC1L1 is regulated by SHP, we examined NPC1L1 expression in WT- and SHP-knockout mice. Npc1l1 mRNA levels were higher in fasted SHP-knockout mice than in WT mice, and after refeeding for 6 h, the mRNA levels decreased in WT mice, but increased in SHP-knockout mice (Figure 2A). Consistent with mRNA changes, in SHP-knockout mice, protein levels were elevated compared to WT mice and increased dramatically after refeeding, but contrary to mRNA changes, NPC1L1 levels in WT mice increased after refeeding (Figure 2B, 2C).

Figure 2. Effects of fasting and refeeding on intestinal expression of NPC1L1 in WT and SHP-knockout mice.

(A-C) WT and SHP-knockout (KO) mice were fasted overnight and refed normal chow for 6 h, and mRNA (A) and protein (B) levels in the pooled jejunum and ileum were measured. (C) NPC1L1 protein was detected by immunohistochemistry in sections of the jejunum. (D-E) WT and SHP-knockout mice were fasted overnight and refed normal chow for the indicated times, and pre-mRNA and protein levels of NPC1L1 in the pooled jejunum and ileum were determined by RT-qPCR and IB, respectively for WT (D) and SHP-knockout (E) mice. (A, B, D, E) Statistical significance was determined by (A, B) two-way or (D, E) one-way ANOVA with the FDR post-test, (SEM, n=3 to 5, *P <0.05, **P <0.01, NS, statistically not significant).

To understand the discrepancy between changes in NPC1L1 mRNA and protein levels, pre-mRNA levels, indicators of gene transcription, were measured. In WT mice, pre-mRNA levels of Npc1l1 increased about 2-fold by 2 h after feeding and then decreased by 6 h to about 60% of the initial fasted level (Figure 2D). In contrast, protein levels in WT mice increased about 3-fold by 2 h and remained elevated up to 6 h (Figure 2D). These results are consistent with a transient increase in Npc1l1 transcription and further suggest that the NPC1L1 protein is stabilized after feeding. In contrast, in SHP-knockout mice, both pre-mRNA and protein levels of NPC1L1 were persistently elevated up to 6 h after feeding (Figure 2E). These results indicate that expression of Npc1l1 is transiently increased early after feeding and that the decrease in its expression in the late-fed state is dependent on SHP.

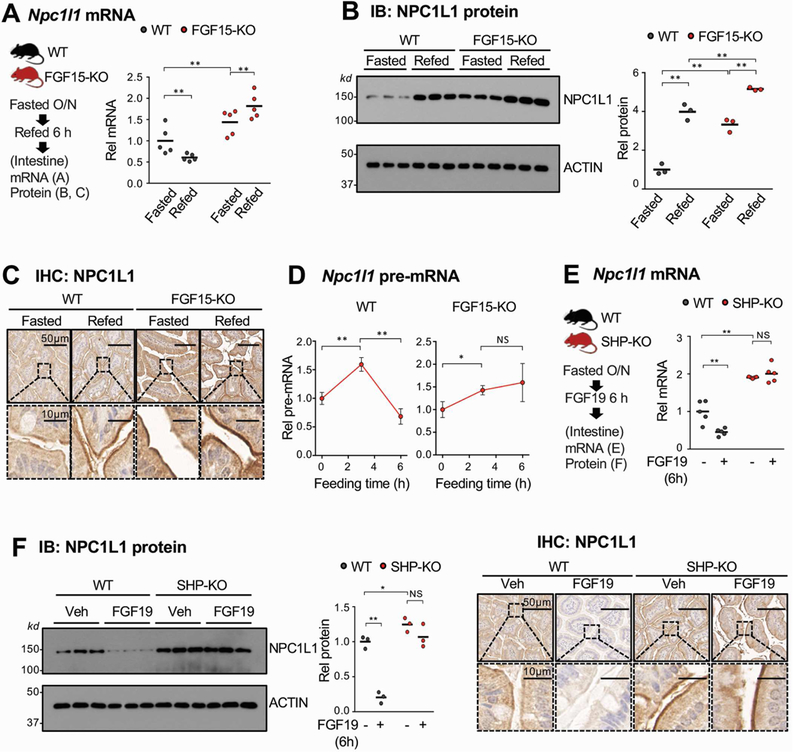

Intestinal NPC1L1 expression is highly elevated in FGF15-knockout mice.

FGF15/19 is a late fed-state hormone that is induced by BA-activated FXR in the ileum and mediates postprandial metabolic responses12, 27, 31. Since nuclear localization, protein stability, and gene-repression functions of SHP are significantly enhanced by FGF15/19 signaling10, 14, 17, 18, we next examined whether repression of Npc1l1 by SHP involved endogenous FGF15 signaling utilizing FGF15-knockout mice. Npc1l1 mRNA levels decreased after feeding for 6 h in WT mice, and mRNA levels were elevated in fasted FGF15-knockout mice and increased further after feeding (Figure 3A), similar to the SHP-knockout mice results. Levels of NPC1L1 were elevated 6 h after feeding in WT mice and were highly elevated in FGF15-knockout mice compared to WT mice (Figure 3B, 3C). Pre-mRNA levels were only transiently increased after feeding in WT mice but were persistently elevated in FGF15-knockout mice (Figure 3D), as in SHP-knockout mice (Figure 2E). As in the FGF15-knockout mice, treatment with FGF19 decreased both mRNA and protein levels of NPC1L1 in WT mice, but not in SHP-knockout mice (Figure 3E, 3F). These results demonstrate that repression of intestinal expression of Npc1l1 in the late fed-state is dependent on both FGF19 and SHP.

Figure 3. Effects of fasting and refeeding on intestinal expression of NPC1L1 in WT and FGF15-knockout mice.

(A-C) WT and FGF15-knockout (KO) mice were fasted overnight and refed normal chow for 6 h and mRNA (A) and protein (B) levels in the pooled jejunum and ileum were measured. (C) NPC1L1 protein was detected by immunohistochemistry in sections of the jejunum. (D) WT and FGF15-knockout mice were fasted overnight and refed normal chow for 3 or 6 h, and pre-mRNA levels in the pooled jejunum and ileum were determined by RT-qPCR. (E-F) WT and SHP-knockout mice were fasted overnight and injected with FGF19 (1 mg/kg) via the tail vein and sacrificed 6 h later. Levels of Npc1l1 mRNA (E) and protein (F, left and middle) in the pooled jejunum and ileum were determined by RT-qPCR and IB, respectively. (F, right) NPC1L1 protein was detected by IHC in sections of the jejunum. (A, B, D, E, F) Statistical significance was determined by (A, B, E, F) two-way or (D) one-way ANOVA with the FDR post-test, (SEM, n=3 to 5, *P <0.05, **P <0.01, NS, statistically not significant).

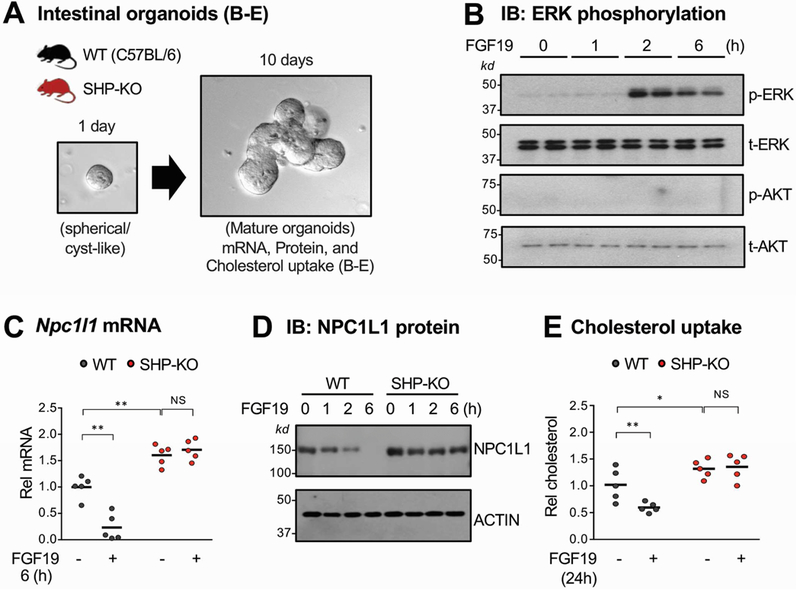

FGF19-mediated inhibition of NPC1L1 expression and sterol uptake in intestinal organoids is dependent on SHP.

To determine if SHP regulation of NPC1L1 expression was a specific intestinal effect, we utilized intestinal organoids from SHP-knockout or WT mice (Figure 4A). FGF19 treatment activated ERK12, 14, 17 but not Akt (Figure 4B, Supplementary Figure 2), demonstrating functional FGF19 signaling in the organoids. FGF19 treatment decreased mRNA (Figure 4C) and protein (Figure 4D) levels of NPC1L1 in WT organoids, and levels were increased in SHP-knockout organoids but were not decreased by FGF19 treatment. Consistent with these results, cholesterol uptake was decreased after FGF19 treatment in WT, but not in SHP-knockout, organoids (Figure 4E). These results indicate that FGF19 inhibits expression of NPC1L1 and sterol uptake in an intestinal cell-autonomous and SHP-dependent manners.

Figure 4. Effects of FGF19 treatment on NPC1L1 expression and cholesterol uptake in intestinal organoids from WT and SHP-knockout mice.

(A) The jejunum and ileum were isolated from WT or SHP-knockout (KO) mice, pooled, and intestinal organoids were cultured and maintained for 10 days as described in Methods. (B-D) Organoids were treated with 50 ng/ml FGF19 for the indicated times. (B) Levels of phosphorylated ERK were determined by IB. (C-D) NPC1L1 mRNA (C) and protein (D) levels were determined by RT-qPCR and IB, respectively. (E) Organoids were cultured in the IntestiCult™ Organoid Growth Medium containing NBD-cholesterol and treated with vehicle or 50 ng/ml FGF19 for 24 h. After washing with PBS, the fluorescence in the cells was determined with excitation at 485 nm and emission at 535 nm as described in Methods. (C, E) Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA with the FDR post-test, (SEM, n=5, *P <0.05, **P <0.01, NS, statistically not significant).

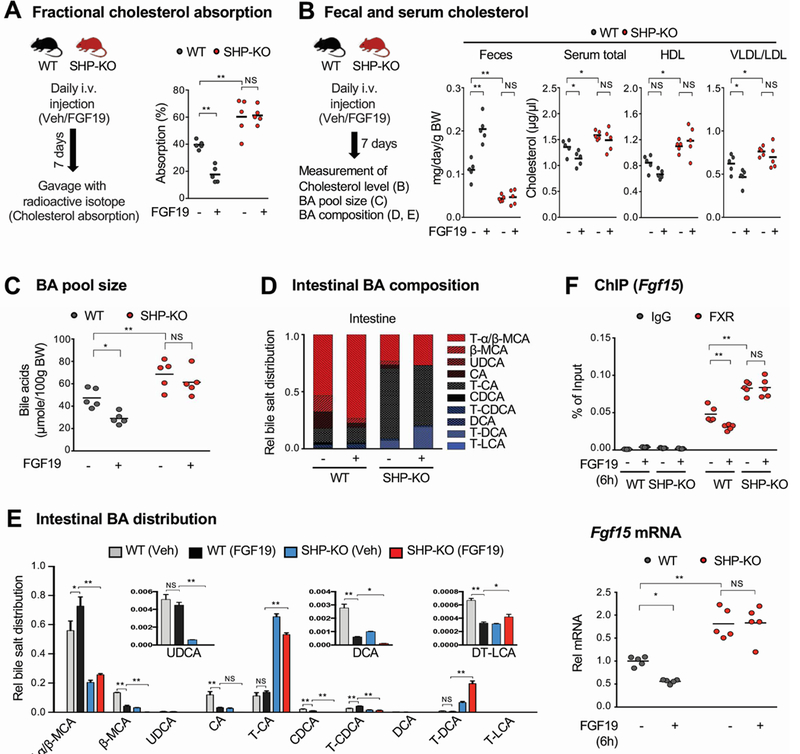

FGF19-mediated inhibition of fractional cholesterol absorption in mice is dependent on SHP.

To examine the effect of FGF19 treatment on fractional cholesterol absorption in vivo, radioactive [14C]cholesterol and [3H]sitosterol were administered by gavage to WT mice or SHP-knockout mice that had been injected with FGF19 for 1 week, and fecal radioactivity was measured over a 24 h period (Figure 5A, left). In WT mice, FGF19 treatment reduced absorption from about 40% to 20% (Figure 5A, right), while in SHP-knockout mice, 60% of radioactive cholesterol was absorbed with or without FGF19. Further, FGF19 treatment increased fecal cholesterol levels WT mice, while fecal levels were decreased in SHP-knockout mice and not affected by FGF19 (Figure 5B). Serum cholesterol and lipoprotein levels were significantly reduced by FGF19 treatment in WT, but not in SHP-knockout, mice (Figure 5B). These results indicate that SHP is important for FGF19-mediated inhibition of fractional cholesterol absorption in mice.

Figure 5. Effects of 1-week treatment of FGF19 on cholesterol absorption excretion in WT and SHP-knockout mice.

(A-E) WT and SHP-knockout (KO) mice were treated daily with vehicle or FGF19 for 7 days and then caged individually. Mice were fasted overnight and refed normal chow for 24 h. (A, left) Experimental outline. (A, right) [14C]cholesterol and [3H]sitosterol were administered by gavage and 1 mg/kg FGF19 or vehicle was injected i.v. at the time of refeeding. Fractional cholesterol absorption was determined as described in the legend to Figure 1E. (B, left) Experimental outline. (B, right) Feces and serum were collected 24 h after refeeding and cholesterol and lipoproteins levels were measured. Fecal cholesterol levels are normalized to body weight. (C) The BA pool size was measured after pooling liver, gallbladder, and intestine (jejunum and ileum) tissues. (D-E) BA compositions were measured in the intestine (jejunum and ileum), and the relative distribution of intestinal bile acids is represented in the stacked bar chart (D) and the fraction of the individual bile acids in each of the mouse groups is plotted (E). (F) Mice were injected i.v. with 1 mg/kg FGF19 or vehicle and 6 h later the mice sacrificed and the jejunum and ileum were collected. (F, up) FXR occupancy at the Fgf15 promoter was measured by ChIP. (F, down) Fgf15 mRNA levels were measured by RT-qPCR. (A, B, C, E, F) Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA with the FDR post-test, (SEM, n=5, *P <0.05, **P <0.01, NS, statistically not significant).

In SHP-knockout mice, BA composition is substantially altered and the FGF19-mediated increase in hydrophilic BA levels are blunted.

Since BA pool size and composition are important determinants of cholesterol levels by modulating cholesterol absorption and TICE5, 32, 33, we next examined the effect of SHP and FGF19 on the tissue BA pool size in gallbladder, liver and intestine and BA composition in the intestine in both WT and SHP-knockout mice. FGF19 treatment for 1 week resulted in decreases in tissue BA pool size (Figure 5C) and relative increases in levels of intestinal hydrophilic BAs, including tauro-α/β−muricholic acids, in WT mice (Figure 5D, 5E, Supplementary Figure 3). Remarkably, BA composition was substantially altered in SHP-knockout mice, with decreases in hydrophilic BAs and increases in hydrophobic BAs, and FGF19-mediated effects on altered BA composition was blunted in SHP-knockout mice.

Since FGF19 treatment increased levels of the hydrophilic BAs, tauro-α/β−muricholic acids that are known FXR antagonists34, we next assessed FXR signaling by examining the binding of FXR at the Fgf15 gene, a known direct FXR target9, and expression of Fgf15. FGF19 treatment decreased FXR occupancy at Fgf15 and decreased Fgf15 gene expression in WT mice, but these effects were absent in SHP-knockout mice (Figure 5F). Thus, the SHP-dependent effects on BA pool size and composition correlate with SHP-dependent changes in FXR transcriptional activity. These findings, together with Npc1l1 expression studies above, suggest that in addition to repression of Npc1l1, altered BA pool size and composition may further contribute to inhibition of cholesterol absorption mediated by FGF19 and SHP.

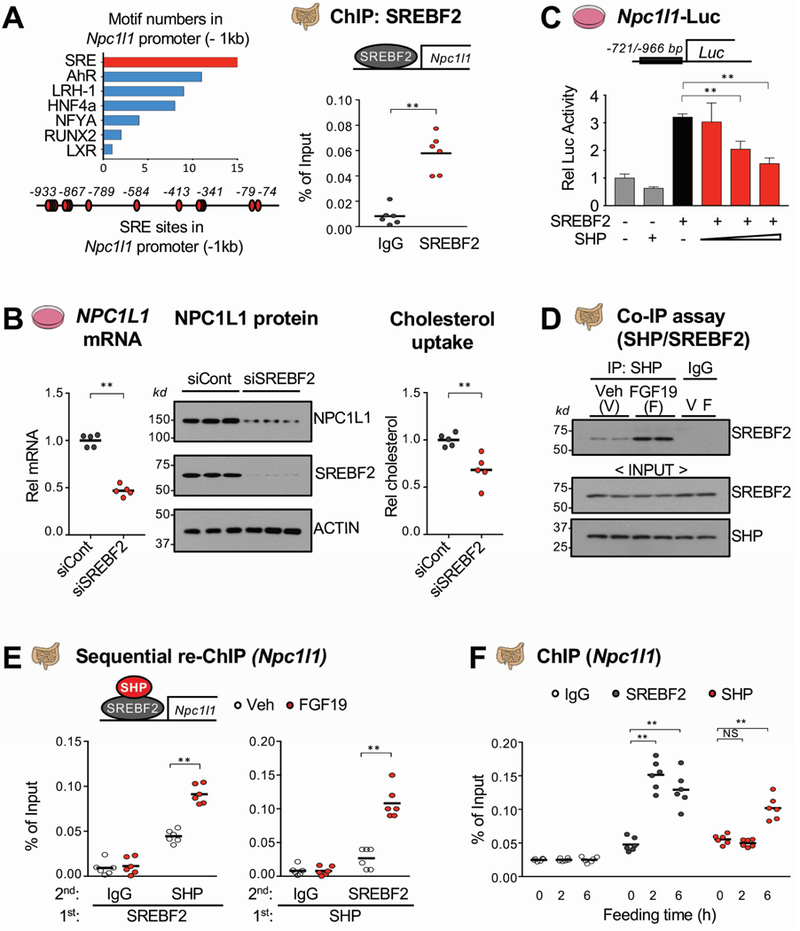

SREBF2 activation of expression of Npc1l1 in intestinal cells is inhibited by SHP.

To elucidate the transcriptional mechanism by which SHP inhibits intestinal expression of Npc1l1, we first examined the occupancy of SHP at the Npc1l1 gene from −935 bp to +74 bp. SHP binding was detected in two regions of the Npc1l1 promoter, centered on about −200 bp and −800 bp (Supplementary Figure 4). SHP is recruited to genes through its interaction with transcription factor(s)10, 13, 14, 19. Binding motifs for several factors, including SREBFs, were identified in these regions (Figure 6A, left). Since multiple SREs were detected at the Npc1l1 gene promoter, intestinal expression of Npc1l1 is activated by SREBF2 and to a much lesser extent by SREBF135–37, and SREBF2 expression strongly correlates with NPC1L1 expression in hyperlipidemia patients38, we focused mechanistic studies on SREBF2.

Figure 6. Inhibition of SREBF2-mediated transactivation of Npc1l1 expression by SHP.

(A) Motifs in about −1 kb of the Npc1l1 promoter (left) were identified using the JASPAR motif database and SREBF2 occupancy at the Npc1l1 promoter was determined by ChIP assay (right). (B) HT29 cells were transfected with siSREBF2 for 48 h and NPC1L1 mRNA (left) and protein (middle) levels were determined. NBD-cholesterol uptake (right) was determined as described in the legend to Figure 4E. (C) HT29 cells were transfected with plasmids as indicated for 48 h, then luciferase activity was measured and normalized to β-galactosidase activity. (D-E) WT mice were fasted overnight and injected with FGF19 (1 mg/kg) via tail vein, and 1 h later, the jejunum and ileum of intestine were removed for analysis. The interaction of SHP and SREBF2 was determined by Co-IP (D) and their co-occupancy at the Npc1l1 promoter was determined by sequential re-ChIP assay (E). (F) WT mice were fasted overnight and refed normal chow for 2 h or 6 h and SREBF2 and SHP occupancy using pooled jejunum and ileum samples were determined by ChIP assay. (A, B, C, E, F) Statistical significance was determined by (A, B) the Student’s t-test, (C) one-way ANOVA, or (E, F) two-way ANOVA with the FDR post-test, (SEM, n=6, *P <0.05, **P <0.01, NS, statistically not significant).

SREBF2 occupancy at the Npc1l1 promoter was readily detected in the −800 bp region by ChIP assay (Figure 6A, right). Next, human intestinal HT29 cells were used as a cell culture model because these cells express NPC1L1 and robustly respond to FGF19 signaling39. Downregulation of SREBF2 with siRNA in intestinal HT29 cells decreased mRNA and protein levels of NPC1L1 and cholesterol uptake (Figure 6B). Further, expression of increasing amounts of SREBF2 progressively increased Npc1l1 promoter activity in a luciferase reporter, and mutation of the two highest scoring SRE sequences largely blocked the increase (Supplementary Figure 5). Further, expression of SHP repressed SREBF2-mediated transactivation of the Npc1l1 promoter (Figure 6C). These results suggest that SHP interacts with and inhibits SREBF2 activation of the Npc1l1 promoter.

The interaction of SHP with SREBF2 in intestinal extracts was detected by CoIP and was increased by FGF19 (Figure 6D). In re-ChIP assays, FGF19 treatment increased SHP levels in SREBF2-bound Npc1l1 chromatin and conversely, increased SREBF2 levels in SHP-bound Npc1l1 chromatin (Figure 6E), indicating co-occupancy of SHP and SREBF2. In ChIP assays, binding of SREBF2 at the Npc1l1 promoter was detected as early as 2 h after feeding and sustained to 6 h, while increased SHP binding was detected only at 6 h after feeding (Figure 6F), which is consistent with increased Npc1l1 pre-mRNA levels at 2 h and decreased levels at 6 h (Figure 2D). These results suggest that SREBF2 activates Npc1l1 early after feeding and that in the late fed-state, FGF19 mediates recruitment of SHP by SREBF2 to the Npc1l1 promoter and the inhibition of SREBF2 transactivation.

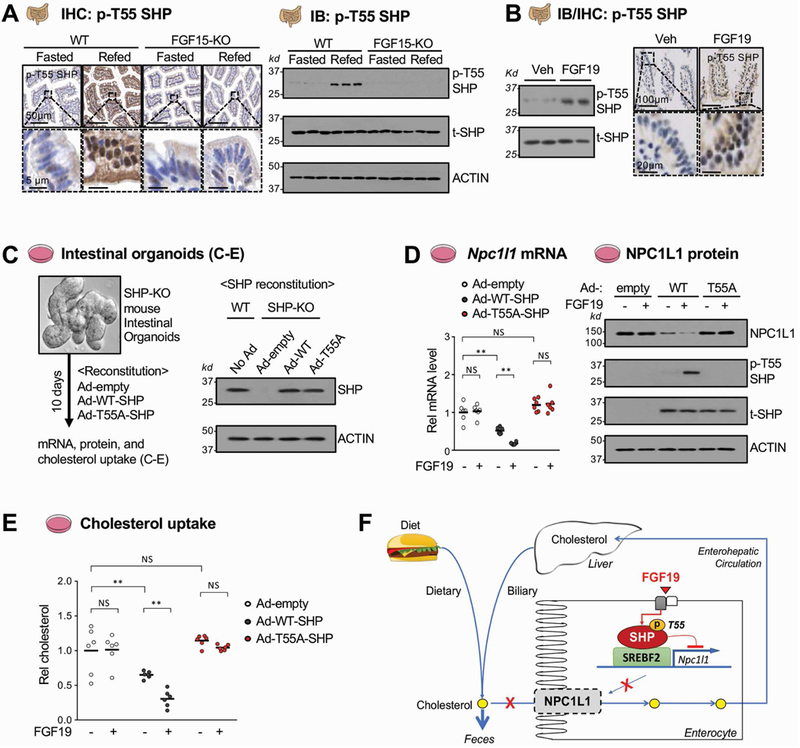

Intestinal SHP is phosphorylated at Thr-55 after feeding or FGF19 treatment in mice.

The gene repression functions of SHP are enhanced by signal-induced post-translational modifications, such as phosphorylation and SUMOylation, which involves its nuclear translocation and inhibition of ubiquitin-proteasomal degradation17, 18, 20. Feeding or FGF19 treatment resulted in phosphorylation of SHP at Thr-55, which promoted its nuclear localization and repression of BA and cholesterol synthetic genes in hepatocytes10, 11, 18. We, thus, next asked whether FGF19 mediates phosphorylation of SHP in the intestine. Refeeding for 6 h after fasting increased levels of SHP phosphorylated at Thr-55 (p-T55-SHP) in WT mice detected by IHC or IB with an antibody specific for p-T55-SHP 10, 18, 20, but this increase was absent in FGF15-knockout mice, while p-T55-SHP was not detected in control SHP-knockout mice (Figure 7A, Supplementary Figure 6). These results suggest that feeding-increased levels of FGF15 leads to phosphorylation of SHP at Thr-55 in mouse intestine. Consistent with these findings, treatment with FGF19 in mice increased p-T55-SHP levels in the small intestine (Figure 7B). These results indicate that intestinal SHP is phosphorylated at Thr-55 by feeding-induced endogenous FGF15 signaling or by FGF19 treatment.

Figure 7. Effects of FGF19-induced phosphorylation of SHP on NPC1L1 expression and cholesterol uptake in intestinal organoid cells.

(A-B) WT and FGF15-knockout (KO) mice were fasted overnight and refed normal chow (A) or injected with vehicle or 1 mg/kg FGF19 (B) for 6 h. (A) p-T55 SHP was detected by immunohistochemistry (IHC) in sections of the jejunum (left) and by immunoblot using pooled jejunum and ileum (IB, right) from fasted and refed mice. (B) p-T55 SHP was detected in pooled jejunum and ileum by IB (left) or in the jejunum by IHC (right) in vehicle or FGF19 treated mice. (C-E) Intestinal organoids from pooled jejunum and ileum of SHP-knockout mice were cultured and maintained for 10 days. WT-SHP or T55A-SHP were expressed in the cells by infection with Ad-WT-SHP or Ad-T55A-SHP for 3 days and then NPC1L1 mRNA and protein levels and cholesterol uptake were measured. (C) Experimental outline. Protein levels of WT-SHP or T55A-SHP in the organoids measured by IB are shown at the right. (D) The levels of NPC1L1 mRNA (left) or protein (right) after treatment as indicated with 50 ng/ml FGF19 for 6 h measured by RT-qPCR or IB, respectively. (E) The intestinal organoid cells were treated with 50 ng/ml FGF19 and NBD-cholesterol was added to the medium for 24 h, and free cholesterol uptake was determined as described in the legend to Figure 4E. (F) Model: In the late fed-state, FGF15/19 signal-mediated activation of SHP through phosphorylation of Thr-55 is important for transcriptional repression of SREBF2-mediated transactivation of Npc1l1, a key intestinal cholesterol transporter, which therefore inhibits sterol absorption and promotes sterol excretion from the body. (D, E) Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA with the FDR post-test, (SEM, n=6, **P <0.01, NS, statistically not significant).

FGF19-mediated phosphorylation of SHP is important for inhibition of NPC1L1 expression and sterol uptake in intestinal organoids.

To further examine the functional importance of Thr-55 phosphorylation of SHP in intestine, a phospho-defective T55A mutant of SHP was expressed in organoids isolated from SHP-knockout mice (Figure 7C). The mRNA (Figure 7D, left) and protein (Figure 7D, right) levels of NPC1L1 were decreased by expression of WT-SHP and further decreased by FGF19 treatment, while levels were little changed by expression of T55A-SHP with or without FGF19 treatment. Further, FGF19 treatment increased p-T55-SHP levels in organoids expressing WT-SHP, but not T55A-SHP (Figure 7D, right). Consistent with these results, expression of WT-SHP in the organoids decreased sterol uptake, which was further decreased by FGF19 treatment, while the sterol uptake was not decreased by expression of T55A-SHP and FGF19 treatment had no effect (Figure 7E). Similar results were observed in intestinal HT29 cells (Supplementary Figure 7). Collectively, these findings indicate that FGF19 signal-induced phosphorylation of SHP at Thr-55 is important for its inhibition of intestinal NPC1L1 expression and cholesterol uptake.

Discussion

SHP is highly expressed in liver and the intestine, but nearly all previous studies have examined its hepatic functions, including transcriptional repression of BA and cholesterol synthesis, circadian lipid metabolism, one carbon metabolism, and autophagy10, 13, 14, 19, 22, 23. In contrast, little is known about the function of SHP in intestine. In this study, we show that SHP has intestinal functions in repression of cholesterol absorption, in part, by inhibiting expression of NPC1L1 in response to postprandial FGF19 signaling in mice.

Postprandial intestinal expression of NPC1L1 is likely complex and biphasic. Npc1l1 pre-mRNA levels increased to a peak at about 2 h after feeding and then decreased to levels below those in fasting animals by 6 h, suggesting active transcriptional repression in the late-fed state. Our data indicate that the FGF19-SHP axis mediates this active repression of Npc1l1. Pre-mRNA levels only transiently increased 2 h after feeding in WT mice, but increased levels were sustained up to 6 h in both SHP-knockout and FGF15-knockout mice. Further, our data suggested that early after feeding, SREBF2 activates Npc1l1 and that in the late fed-state, SHP and FGF19 inhibit the SREBF2 activity. Consistent with our findings, expression of Npc1l1 and sterol absorption are increased by glucose35, 40 and nuclear levels of SREBF2 are increased by feeding and insulin41. Inhibition by SHP of other known SHP-interacting factors whose binding motifs were detected in the Npc1l1 promoter, such as, LRH-1 or AhR14, 36, may contribute to Npc1l1 repression, but SHP inhibition of SREBF2 is likely primary, given the importance of SREBF2 in the regulation of Npc1l1 and sterol levels 35–38.

Recent studies have shown that nuclear localization and the gene-regulatory function of SHP are enhanced by postprandial FGF19 signaling. In the liver, FGF19 mediates phosphorylation of SHP at Thr-55, which is critical for its interaction with RanBP218, a nuclear pore component and SUMO ligase that promotes nuclear localization of SHP, and for interaction with histone demethylase LSD111, which promotes the gene-repressive function of SHP. Further, FGF19 increases SHP protein stability by inhibiting ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation in hepatocytes17. In the present study, we showed that FGF19 signaling also increases phosphorylation of SHP at Thr-55 in the intestine in mice, in intestinal organoids, and in HT29 cells, and that mutation of Thr-55 in SHP abrogates the inhibition of NPC1L1 and cholesterol uptake in organoids and HT29 cells treated with FGF19. Thus, FGF19 signal-induced phosphorylation of SHP is important for its functions in both the liver and intestine. Collectively, our findings suggest that a postprandial intestinal hormone FGF15/19 increases gene-regulatory function of SHP via phosphorylation at Thr-55, and possibly by stabilization of SHP17, which results in the inhibition of NPC1L1 expression and cholesterol absorption in enterocytes (Model, Figure 7F).

This study focused on NPC1L1 since it is critical for intestinal absorption of both dietary and biliary cholesterol1, 7, 8. Overall, regulation in the intestine of cholesterol, BAs, and lipids by FGF19 and SHP may involve the combined actions of regulation of other genes that were identified in our intestinal RNA-seq analysis of WT and SHP-knockout mice. In addition to regulation of expression of Npc1l1, based on this global analysis and q-RTPCR gene expression studies, SHP may inhibit expression of Acat2, a cholesterol acyltransferase that is important for cholesterol esterification increasing cholesterol absorption efficiency, and Abca1, which is involved in cholesterol efflux 3, 8, 42. Other examples of genes potentially inhibited by SHP are those involved in sterol biosynthesis, including Hmgcr. Thus, SHP and FGF19 may act as key regulators of multiple sterol metabolism and transport network genes in the intestine, which contributes to maintenance of cholesterol homeostasis.

BA composition is important for cholesterol absorption5, 6, 33. While hydrophobic bile acids promote sterol absorption, hydrophilic bile acids, such as, muricholic acids, inhibit it. In the present study, we observed that relative levels of hydrophilic BAs, particularly tauro-α/β−muricholic acids, were substantially decreased in SHP-knockout mice and that FGF19-mediated changes in BA composition were blunted in these mice, suggesting that SHP and FGF19, not only represses expression of NPC1L1, but also alter BA composition, which may contribute to inhibition of fractional cholesterol absorption. Consistent with increased levels of tauro-α/β−muricholic acids, known FXR antagonists34, we observed that FGF19 treatment decreased binding of FXR at Fgf15 and Fgf15 gene expression in a SHP-dependent manner, suggesting that intestinal FXR signaling is feedback repressed by the FGF19-SHP axis. Interestingly, a recent study has shown that activation of intestinal FXR signaling reduces whole body cholesterol levels by promoting TICE via increasing hydrophilic BA levels5. Further studies will be necessary to examine whether the FGF19-SHP axis can regulate cholesterol levels in part by promoting TICE, as well as, by inhibiting intestinal NPC1L1 expression and cholesterol absorption as shown in the present study.

The role of FGF19 and SHP as regulators of sterol metabolism and transport extends beyond the intestine. Recent SHP ChIP-seq studies in livers of FGF19-treated mice revealed that SHP inhibits expression of sterol biosynthetic network genes, including Hmgcr10, as well as BA synthetic genes. FGF19 and SHP inhibit the hepatic synthesis of cholesterol, thus preventing excess levels of cholesterol due to the inhibition of BA synthesis from cholesterol. In addition, enterohepatic BA recycling is also important for reducing cholesterol levels by promoting hepatic conversion of cholesterol into BAs, and BA sequestrants that inhibit this recycling have been used for hypercholesterolemia1, 3, 8, 43. A key ileal BA transporter, Asbt, is important for BA recycling3 and is inhibited by FGF19 signaling44, and high affinity ASBT inhibitors are alternatives to the sequestrants for treating hypercholesterolemia with reduced side effects. In our intestinal RNA-seq analysis, expression of Asbt was increased in SHP-knockout mice. Intriguingly, a recent study has shown that treatment with an oral ASBT inhibitor that interrupts enterohepatic BA circulation protected against non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in obese mice and resulted in reduced hepatic triglyceride and total cholesterol levels and increased fecal BA levels45. FGF19 and SHP, thus, appear to act at both liver and intestine, by targeting multiple network genes important for maintaining sterol and BA homeostasis.

In conclusion, this study identifies SHP and FGF19 as new physiological regulators of cholesterol absorption in the intestine in part by inhibiting the expression of NPC1L1 and by possibly altering BA composition. Endocrine FGF hormones, including FGF19, have great therapeutic potential for treatment of a wide range of human diseases, including metabolic disorders46. Further, NPC1L1 is the molecular target of the cholesterol-lowering drug, ezetimibe7, 24. Thus, the intestinal FGF19-SHP-NPC1L1 axis identified in this study may provide new molecular targets for treating hypercholesterolemia and related disease, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment:

We thank Lucas Li, Director of Metabolomics Center at UIUC, for assistance with the LC-MS analysis and Lydia Lee for technical assistance.

Grant support: This study was supported by an American Heart Association Scientist Development Award (16SDG27570006) to YK, by an American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship to SB (17POST33410223), and by R01 grants from the National Institutes of Health (DK062777 and DK095842) and an Innovative Basic Science Award from the American Diabetes Association (1-16-IBS-156) to JKK.

Abbreviations:

- ABCA1

ATP-binding cassette transporter A1

- ACAT2

cholesterol acyltransferase 2

- AhR

aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- ASBT

apical sodium–bile acid transporter

- BA

bile acid

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation

- FGF15/19

fibroblast growth factor 15/19

- FXR

farnesoid-X-receptor

- Hmgcr

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coA reductase

- IB

immunoblot

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- LSD1

lysine-specific demethylase1

- NPC1L1

NPC1-like intracellular cholesterol transporter 1

- OST α/β

organic solute transporter α/β

- SHP

small heterodimer partner

- SREBF

sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor

- TICE

trans-intestinal cholesterol excretion

- WT

wild type

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Transcript Profiling: The RNA-seq data will be submitted to the GEO database and the accession number will be provided before publication.

Writing Assistance: None.

References

- 1.Kuipers F, Bloks VW, Groen AK. Beyond intestinal soap--bile acids in metabolic control. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol 2014;10:488–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Aguiar Vallim TQ, Tarling EJ, Edwards PA. Pleiotropic roles of bile acids in metabolism. Cell Metab 2013;17:657–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dawson PA, Karpen SJ. Intestinal transport and metabolism of bile acids. J. Lipid Res 2015;56:1085–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiang JY. Bile acid metabolism and signaling. Compr. Physiol 2013;3:1191–1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Boer JF, Schonewille M, Boesjes M, et al. Intestinal Farnesoid X Receptor Controls Transintestinal Cholesterol Excretion in Mice. Gastroenterology 2017;152:1126–1138 e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jakulj L, van Dijk TH, de Boer JF, et al. Transintestinal Cholesterol Transport Is Active in Mice and Humans and Controls Ezetimibe-Induced Fecal Neutral Sterol Excretion. Cell Metab 2016;24:783–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang DQ. Regulation of intestinal cholesterol absorption. Annu. Rev. Physiol 2007;69:221–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Degirolamo C, Sabba C, Moschetta A. Intestinal nuclear receptors in HDL cholesterol metabolism. J. Lipid Res 2015;56:1262–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inagaki T, Choi M, Moschetta A, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 15 functions as an enterohepatic signal to regulate bile acid homeostasis. Cell Metab 2005;2:217–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim YC, Byun S, Zhang Y, et al. Liver ChIP-seq analysis in FGF19-treated mice reveals SHP as a global transcriptional partner of SREBP-2. Genome Biol 2015;16:268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim YC, Fang S, Byun S, et al. FXR-induced lysine-specific histone demethylase, LSD1, reduces hepatic bile acid levels and protects the liver against bile acid toxicity. Hepatology 2015;62:220–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kir S, Beddow SA, Samuel VT, et al. FGF19 as a postprandial, insulin-independent activator of hepatic protein and glycogen synthesis. Science 2011;331:1621–1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsuchiya H, da Costa KA, Lee S, et al. Interactions Between Nuclear Receptor SHP and FOXA1 Maintain Oscillatory Homocysteine Homeostasis in Mice. Gastroenterology 2015;148:1012–1023 e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim YC, Seok S, Byun S, et al. AhR and SHP regulate phosphatidylcholine and S-adenosylmethionine levels in the one-carbon cycle. Nat Commun 2018;9:540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fang S, Miao J, Xiang L, et al. Coordinated recruitment of histone methyltransferase G9a and other chromatin-modifying enzymes in SHP-mediated regulation of hepatic bile acid metabolism. Mol. Cell. Biol 2007;27:1407–1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kemper J, Kim H, Miao J, et al. Role of a mSin3A-Swi/Snf chromatin remodeling complex in the feedback repression of bile acid biosynthesis by SHP. Mol. Cell. Biol 2004;24:7707–7719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miao J, Xiao Z, Kanamaluru D, et al. Bile acid signaling pathways increase stability of Small Heterodimer Partner (SHP) by inhibiting ubiquitin-proteasomal degradation. Genes Dev 2009;23:986–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim DH, Kwon S, Byun S, et al. Critical role of RanBP2-mediated SUMOylation of Small Heterodimer Partner in maintaining bile acid homeostasis. Nat. Commun 2016;7:12179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Y, Hagedorn CH, Wang L. Role of nuclear receptor SHP in metabolism and cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2011;1812:893–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seok S, Kanamaluru D, Xiao Z, et al. Bile acid signal-induced phosphorylation of small heterodimer partner by protein kinase Czeta is critical for epigenomic regulation of liver metabolic genes. J. Biol. Chem 2013;288:23252–23263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim SC, Kim CK, Axe D, et al. All-trans-retinoic acid ameliorates hepatic steatosis in mice by a novel transcriptional cascade. Hepatology 2014;59:1750–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee SM, Zhang Y, Tsuchiya H, et al. Small heterodimer partner/neuronal PAS domain protein 2 axis regulates the oscillation of liver lipid metabolism. Hepatology 2015;61:497–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Byun S, Kim YC, Zhang Y, et al. A postprandial FGF19-SHP-LSD1 regulatory axis mediates epigenetic repression of hepatic autophagy. EMBO J 2017;36:1755–1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis HR Jr., Zhu LJ, Hoos LM, et al. Niemann-Pick C1 Like 1 (NPC1L1) is the intestinal phytosterol and cholesterol transporter and a key modulator of whole-body cholesterol homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem 2004;279:33586–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xie C, Zhou ZS, Li N, et al. Ezetimibe blocks the internalization of NPC1L1 and cholesterol in mouse small intestine. J. Lipid Res 2012;53:2092–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou M, Luo J, Chen M, et al. Mouse species-specific control of hepatocarcinogenesis and metabolism by FGF19/FGF15. J. Hepatol 2017;66:1182–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katafuchi T, Esterhazy D, Lemoff A, et al. Detection of FGF15 in Plasma by Stable Isotope Standards and Capture by Anti-peptide Antibodies and Targeted Mass Spectrometry. Cell Metab 2015;21:898–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fu L, John LM, Adams SH, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 19 increases metabolic rate and reverses dietary and leptin-deficient diabetes. Endocrinology 2004;145:2594–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ge L, Wang J, Qi W, et al. The cholesterol absorption inhibitor ezetimibe acts by blocking the sterol-induced internalization of NPC1L1. Cell Metab 2008;7:508–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kraus D, Yang Q, Kahn BB. Lipid Extraction from Mouse Feces. Bio Protoc 2015;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Lundasen T, Galman C, Angelin B, et al. Circulating intestinal fibroblast growth factor 19 has a pronounced diurnal variation and modulates hepatic bile acid synthesis in man. J. Intern. Med 2006;260:530–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang DQ, Tazuma S, Cohen DE, et al. Feeding natural hydrophilic bile acids inhibits intestinal cholesterol absorption: studies in the gallstone-susceptible mouse. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol 2003;285:G494–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu Y, Li F, Zalzala M, et al. Farnesoid X receptor activation increases reverse cholesterol transport by modulating bile acid composition and cholesterol absorption in mice. Hepatology 2016;64:1072–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sayin SI, Wahlstrom A, Felin J, et al. Gut microbiota regulates bile acid metabolism by reducing the levels of tauro-beta-muricholic acid, a naturally occurring FXR antagonist. Cell Metab 2013;17:225–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malhotra P, Boddy CS, Soni V, et al. D-Glucose modulates intestinal Niemann-Pick C1-like 1 (NPC1L1) gene expression via transcriptional regulation. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol 2013;304:G203–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iwayanagi Y, Takada T, Suzuki H. HNF4alpha is a crucial modulator of the cholesterol-dependent regulation of NPC1L1. Pharm. Res 2008;25:1134–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kikuchi T, Orihara K, Oikawa F, et al. Intestinal CREBH overexpression prevents high-cholesterol diet-induced hypercholesterolemia by reducing Npc1l1 expression. Mol Metab 2016;5:1092–1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Widdowson WM, McGowan A, Phelan J, et al. Vascular Disease Is Associated With the Expression of Genes for Intestinal Cholesterol Transport and Metabolism. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 2017;102:326–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vergnes L, Lee JM, Chin RG, et al. Diet1 functions in the FGF15/19 enterohepatic signaling axis to modulate bile acid and lipid levels. Cell Metab 2013;17:916–928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ravid Z, Bendayan M, Delvin E, et al. Modulation of intestinal cholesterol absorption by high glucose levels: impact on cholesterol transporters, regulatory enzymes, and transcription factors. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol 2008;295:G873–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miao J, Haas JT, Manthena P, et al. Hepatic insulin receptor deficiency impairs the SREBP-2 response to feeding and statins. J. Lipid Res 2014;55:659–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Boer JF, Kuipers F, Groen AK. Cholesterol Transport Revisited: A New Turbo Mechanism to Drive Cholesterol Excretion. Trends Endocrinol. Metab 2018;29:123–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li T, Chiang JY. Bile Acid signaling in liver metabolism and diseases. J Lipids 2012;2012:754067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sinha J, Chen F, Miloh T, et al. beta-Klotho and FGF-15/19 inhibit the apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter in enterocytes and cholangiocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol 2008;295:G996–G1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rao A, Kosters A, Mells JE, et al. Inhibition of ileal bile acid uptake protects against nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in high-fat diet-fed mice. Sci. Transl. Med 2016;8:357ra122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Degirolamo C, Sabba C, Moschetta A. Therapeutic potential of the endocrine fibroblast growth factors FGF19, FGF21 and FGF23. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2016;15:51–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.