Abstract

Background & Aims:

Although there are associations among oxidative stress, NADPH oxidase (NOX) activation, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) development, it is not clear how NOX contributes to hepatocarcinogenesis. We studied the functions of different NOX proteins in mice following administration of a liver carcinogen.

Methods:

Fourteen-day-old Nox1−/− mice, Nox4−/– mice, Nox1−/−; Nox4−/− (double knockout) mice, and wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 mice were given a single intraperitoneal injection of diethylnitrosamine (DEN) and liver tumors were examined at 9 months. We also studied the effects of DEN in mice with disruption of Nox1 specifically in hepatocytes (Nox1ΔHep), hepatic stellate cells (Nox1ΔHep), or macrophage (Nox1ΔMac). Some mice were also given injections of the NOX1 specific inhibitor ML171. To study the acute effects of DEN, 8–12 week old mice were given a single intraperitoneal injection, and liver and serum were collected at 72 hrs. Liver tissues were analyzed by histology, quantitative PCR, and immunoblots. Hepatocytes and macrophages were isolated from WT and knockout mice and analyzed by immunoblots.

Results:

Nox4−/− mice and WT mice developed liver tumors within 9 months after administration of DEN, whereas Nox1−/− mice developed 80% fewer tumors, which were 50% smaller than those of WT mice. Nox1ΔHep and Nox1ΔHSC mice developed liver tumors of the same number and size as WT mice, whereas Nox1ΔMac developed fewer, smaller tumors, similar to Nox1−/− mice. Following DEN injection, levels of tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin 6 (IL6) and phosphorylated STAT3 were increased in livers from WT, but not Nox1−/− or Nox1ΔMac mice. Conditioned medium from necrotic hepatocytes induced expression of NOX1 in cultured macrophages, followed by expression of TNF, IL6, and other inflammatory cytokines; this medium did not induce expression of IL6 or cytokines in Nox1ΔMac macrophages. WT mice given DEN followed by ML171 developed fewer and smaller liver tumors than mice given DEN followed by vehicle.

Conclusions:

In mice given injections of a liver carcinogen (DEN), expression of NOX1 by macrophages promotes hepatic tumorigenesis by inducing the production of inflammatory cytokines. We propose that upon liver injury, damage-associated molecular patterns released from dying hepatocytes activate liver macrophages to produce cytokines that promote tumor development. Strategies to block NOX1 or these cytokines might be developed to slow HCC progression.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Inflammation, Reactive oxygen species, Macrophage

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most prevalent subtype of liver cancer, accounting for 80% of primary liver cancers1. Etiological studies have revealed a number of HCC risk factors, including hepatitis B virus2 and Hepatitis C virus3 infections, excessive alcohol consumption and metabolic disorders (e.g. obesity4, diabetes5, 6, and metabolic syndrome7). Although the successful development of vaccines and anti-viral therapies has dramatically reduced the prevalence of hepatitis viral infection during the past two decades, the mortality rate of HCC has been continuously rising, despite the opposite trend seen in other malignancies. The unprecedented rise of HCC is at least partially related to the epidemic spread of obesity that affects over 38% of the US population8. Current treatment schemes for non-viral HCC are limited, making it the fastest growing cancer type in the US9.

Liver injury, as a result of metabolic stress or exposure to toxic substances and microbial pathogens, is characterized by hepatocyte injury and death that leads to the infiltration of inflammatory cells aiming to clear cellular debris, promote liver repair/regeneration and restore homeostasis10. However, dysregulation of this process often promotes development of HCC11. Mechanistically, persistent hepatocyte death leads to liver infiltration of immune cells which chronically produce inflammatory cytokines (i.e. TNF and IL-6) that positively correlate with HCC progression in humans12–15. This would ultimately establish a microenvironment that favors survival and proliferation of hepatocytes harboring oncogenic mutations after the initial liver damage, thereby promoting HCC development8.

The generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the liver after injury is shown to contribute to DNA damage and epigenetic modifications, resulting in accumulation of mutations that may activate oncogenes and/or inactivate tumor suppressors16. Accumulating evidence has suggested a critical role of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidases (NOXs), multi-component complexes that catalyze reactions to generate superoxide and hydrogen peroxide from molecular oxygen, in the pathogenesis of various liver diseases17, 18. Seven NOX family members have been identified, including NOX1–5, dual oxidase 1, and dual oxidase 219, 20, although the precise function of each member remains incompletely understood under physiological and pathological conditions.

NOX1 and NOX4, two major NOX isoforms expressed in the liver21, have been implicated in the progression of liver diseases, including viral hepatitis22, alcohol-induced hepatitis23, cholestatic liver injury24, liver fibrosis25–27, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis28, 29 and HCC30. To study the role of NOXs in HCC, we used diethylnitrosamine (DEN), a carcinogen that induces liver damage, neutrophilic infiltration, centrilobular hemorrhagic necrosis, bile duct proliferation, and bridging necrosis that ultimately progresses to HCC31. DEN is specifically metabolized by CYP2E1 in zone 3 hepatocytes 32, and its metabolic products cause DNA damage, hepatocyte death and subsequent compensatory proliferation of surviving hepatocytes, which can ultimately give rise to HCC when oncogenic mutations accumulate14, 33.

Using a combination of genetic, pathological, biochemical and molecular approaches, this study demonstrates that NOX1, but not NOX4, is required for DEN induced HCC. Unexpectedly, we find that expression of NOX1 in hepatocytes or hepatic stellate cells does not regulate HCC development. Rather, the ablation of NOX1 in macrophages dramatically abolishes NOX1’s HCC promoting activity by dampening inflammatory cytokine production from macrophages. The anti-tumor effect seen in mice treated with a NOX1-specific inhibitor may open up new avenues for HCC treatment in humans. Lastly, our study also suggests that macrophage-produced ROS do not directly induce hepatocyte damage, but rather promote the survival of oncogene-harboring mutant hepatocytes via orchestrating cytokine production, thereby accelerating HCC development.

METHODS

Mice.

Eight-week-old Nox1−/− mice34, Nox4−/− mice34, Nox1F/F mice35, Albumin-Cre mice (The Jackson Laboratory; 03574), Lrat-Cre mice36, LysM-Cre mice (The Jackson Laboratory; 004781), and WT littermates on a C57BL/6 background were maintained under pathogen–free conditions at UCSD and had ad libitum access to normal chow and water. To induce HCC, 14-days old males were i.p. injected with 25 mg/kg DEN (Sigma N0258). For acute DEN studies 8–12 weeks old male mice were i.p. injected with 100 mg/kg DEN (Sigma N0258), and liver and serum were analyzed within the first 72 hrs. Only male mice were used and experiments were approved by the University of California San Diego Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Serum ALT measurements.

Serum ALT measurements were analyzed using Infinity ALT (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and a VALIDATE calibration verification kit (Maine Standards Company LLC).

Histology.

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded human or mouse livers were stained with Haemotoxylin and Eosin (H&E). Human livers were immunostained with anti-human NOX1 (GeneTex, GTX103888); antihuman CD68 (Proteintech, 66231–1-Ig). Mouse livers were stained with anti-mouse NOX1 (Abcam, ab55831): anti-mouse AFP (Biocare, SKU028); anti-mouse YAP-1 (Cell Signaling, CST8418); anti-mouse Ki67 (Genetex, GTX16667); anti-mouse Desmin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, RB-9014-P0); and anti-mouse F4/80 (eBioscience, 14–4801-82) Abs, followed by staining with DAB (Vector Laboratories) or with secondary Alexa Fluor 594 or Alexa Flour 488 conjugated Abs. Images were taken using an Olympus microscope, and positive areas were calculated using ImageJ software (NIH).

Cell culture.

Primary bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) were generated by culturing mouse bone marrow cells in the presence of 20% vol/vol L929 conditional medium for 7 days as described37. Primary hepatocytes were isolated from 8–12 weeks old male mice by perfusing the liver with collagenase as described before25. Conditioned medium of necrotic hepatocytes (lysed by three cycles of freezing and thawing) were added onto 6cm dishes with BMDMs and incubated at 37C for 4h.

RT-qPCR.

Total RNA was isolated from livers or BMDMs using RNeasy columns (QIAGEN). Expression levels of selected genes were calculated after normalization to the standard housekeeping gene HPRT (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific) using the ΔΔCt method. The data represent relative mRNA levels compared with control levels (mean ± SEM, P < 0.05).

Western blot (WB) analysis.

WB analysis was performed on cell or tissue lysates that were separated by SDS/PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The primary antibodies and dilutions were as follows: beta actin (A5441, Sigma) at 1:5000, pStat3 (#9145; Cell Signaling Technology) at 1:2000; Stat3 (#9139; Cell Signaling Technology) at 1:2000, ERK1/2 (#9107; Cell Signaling Technology) at 1:2000, pERK1/2 (#4370; Cell Signaling Technology) at 1:2000, p-H2AX (#9718, Cell Signaling Technology) at 1:1000, pAKT (#9271; Cell Signaling Technology) at 1:1000, AKT (sc-8312; Santa Cruz) at 1:1000, p-P38 (#9211; Cell Signaling Technology) at 1:1000, P38 (sc-535; Santa Cruz) at 1:200, pJNK (#9251; Cell Signaling Technology) at 1:1000, JNK1/2 (#554285; BD Pharmingen) at 1:500, pIKKα/β (#2697, Cell Signaling Technology) at 1:1000, IKKα (#136A Imgenex) at 1:1000, p-P65 (#3031, Cell Signaling Technology), P65 (c-20) (sc-372, Santa Cruz) at 1:1000.

Patient specimens.

HCC liver tissues were obtained from patients with diagnosed HCC who underwent liver transplantation. All clinical liver specimens were from the Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University (Guangzhou, China). Informed consent in writing was obtained from patients. This study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki Principles.

Statistics.

All data represent the mean ± SEM. Comparisons of 2 groups were analyzed using an unpaired, 2-tailed Student’s t test. Comparisons of 3 or more groups were analyzed using ANOVA. ANOVA with a Dunnett’s test was used for comparing multiple groups of mice or treatments with controls. ANOVA with a Bonferroni’s test was used when making multiple pair-wise comparisons between different groups. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (Prism 7 version 7.0c; GraphPad Software).

Study approval.

All mice were maintained under specific pathogen–free conditions at UCSD according to UCSD IACUC protocol S07088. For human subjects, written informed consent was obtained from each patient in accordance with the ethics guidelines for epidemiological research in China.

RESULTS

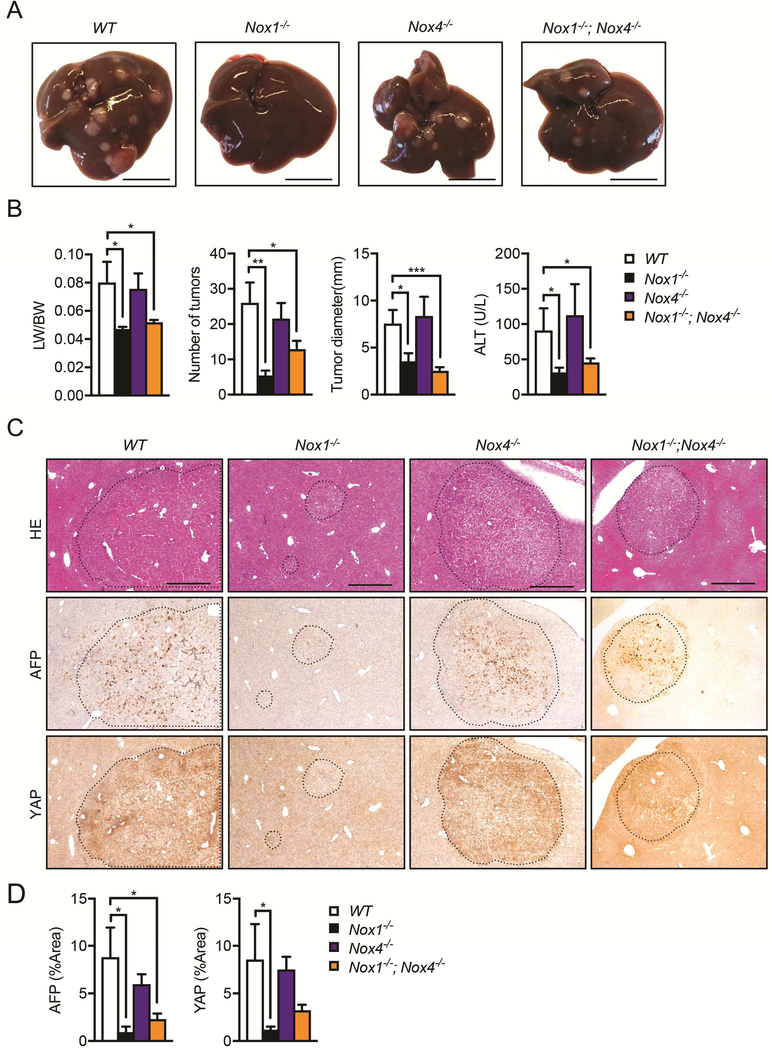

NOX1, but not NOX4, promotes HCC development

To investigate the roles of NOX1 and NOX4, two major NOX isoforms expressed in the liver, in HCC development, we compared DEN-induced HCC carcinogenesis in Nox1−/− and Nox4−/− mice, which have germline ablation of NOX1 or NOX4. Although deletion of NOX4 did not affect HCC development, NOX1 ablation resulted in ~80% reduction of liver tumor number and 50% decline in maximum tumor size at 9 months-of-age compared to WT mice (Figure 1A, B). In addition, liver:body weight (LW/BW) ratios and the serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) concentrations were also dramatically reduced in Nox1−/−, but not Nox4−/−, mice (Figure 1B). To investigate if NOX1 and NOX4 had interactive effects on tumor progression, we injected Nox1−/−; Nox4−/− double knockout mice with DEN. These mice were comparable to Nox1−/− mice in terms of tumor formation, suggesting that NOX4 deletion had no additional effects on DEN-induced HCC development (Figure 1A and 1B). Moreover, livers of Nox1−/− and Nox1−/−; Nox4−/− mice displayed a reduced staining pattern for HCC markers, such as α fetoprotein (AFP) and Yes-associated protein (YAP)38, relative to those of WT and Nox4−/− mice (Figure 1C and 1D). Similarly, the mRNA levels of HCC markers such as Afp, Yap, Sox9 and Glypican 3 (Gpc3) were also decreased in Nox1−/− and Nox1−/−; Nox4−/− tumors (Figure S1A). Consistently, molecular markers that are associated with angiogenesis and tumor invasion, including vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (Vegfr), platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule (Pecam-1), integrin α1 and integrin β1, were significantly reduced in Nox1−/− and Nox1−/−; Nox4 mice (Figure S1A). However, inflammation markers, including F4/80 and TNF in both tumor and non-tumor regions were unaffected by NOX1 or NOX4 deletion (Figure S1A). Of note, there is no compensational expression of NOX1 or NOX4 in the liver upon deletion of either isoform (Figure S1A). We also observed a dramatic reduction of CYP2E1, a factor that is negatively associated with HCC39, 40, in liver tumor extracts relative to non-tumor livers from both WT and Nox1−/− mice, thereby reaffirming a clear separation of tumor from non-tumor tissues (Figure S1B).

Figure 1. NOX1 controls HCC development.

(A) Representative livers from DEN-injected mice of indicated genotypes 9 month after birth (scale bar, 1 cm). (B) Liver weight:body weight (LW/BW) ratios, tumor numbers and maximum sizes of DEN-induced HCCs. Serum ALT was quantified by Infinity reagent (n≧7 mice per group). (C) Representative liver sections from DEN-injected mice that were stained with H&E, AFP or YAP (scale bar, 0.5 mm). (D) Percentage of positive staining areas of AFP and YAP (n≧7 mice per group). Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. Student’s t-test for independent samples and unequal variances was used to assess statistical significance (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001).

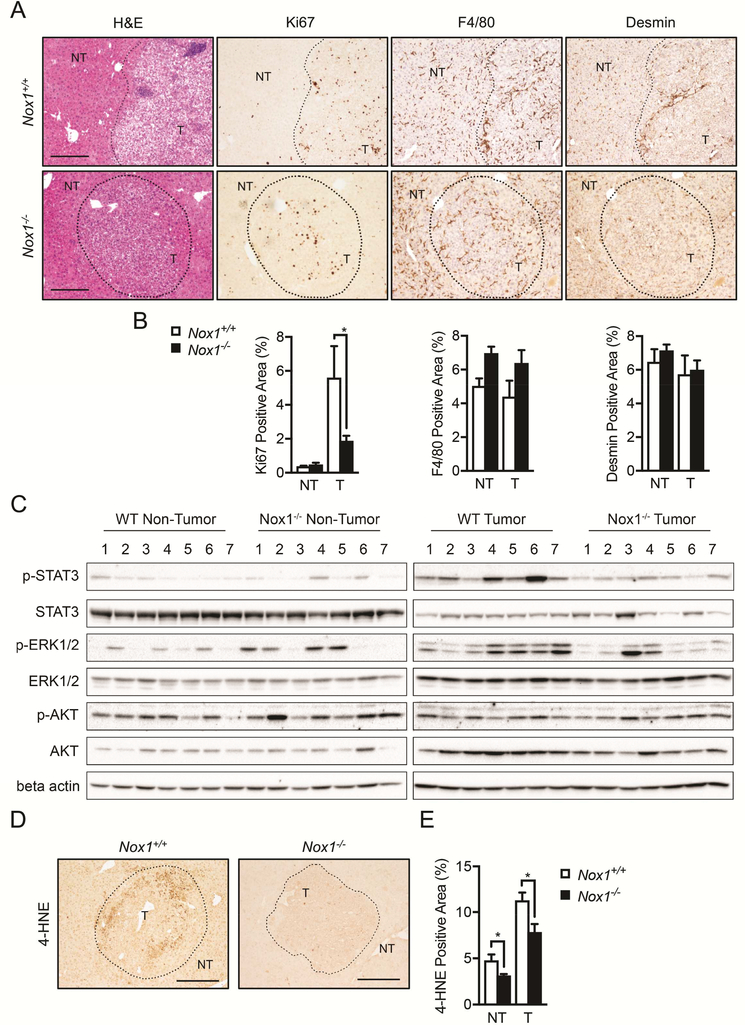

In HCC-bearing mice, NOX1 deficiency resulted in attenuated tumor cell proliferation as indicated by Ki67 staining (Figures 2A and 2B), and defective production of ROS as shown by 4-Hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) staining (Figures 2D and 2E). However, the total numbers of liver macrophages and hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) in the tumors, quantified by F4/80 and Desmin staining respectively (Figures 2A and 2B), were not affected by NOX1 deficiency.

Figure 2. Tumor cell proliferation is reduced in Nox1−/− mice.

(A) Livers were stained with H&E, Ki67 (proliferation marker), F4/80 (marker of macrophages), and Desmin (marker of HSCs). (B) Percentages of positive staining areas of Ki67, F4/80 and Desmin, respectively (n≧6 mice per group). (C) Immunoblot (IB) analysis of p-STAT3, STAT3, p-ERK, ERK, p-AKT, AKT and b-actin in tumor (T) and non-tumor (NT) liver tissues from DEN-injected mice. (D) Representative liver sections that were stained with 4-HNE (4-Hydroxynonenal, marker of ROS). Representative images were taken using objectives x10, Scale bar: 200 μm. (E) Percentages of positive staining areas of 4-HNE (n≧6 mice per group). Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. Student’s t-test for independent samples and unequal variances was used to assess statistical significance (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***<0.001).

STAT3, which is activated by various cytokines and growth factors, including IL-6, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and EGF family members41, 42, is often found to be activated in malignant tumors43, 44, including HCC45, 46. By analyzing the liver tumors, we observed decreased activation of oncogenic transcription factor STAT3 (p-STAT3) and the ERK MAPK cascade in NOX1-deficient mice (Figure 2C). However, the pro-survival signaling component AKT pathway was unaffected (Figure 2C). Hepatocyte-specific deletion of STAT3 (Stat3Δhep) resulted in more than 6-fold reduction in HCC load relative to WT (Stat3F/F) mice47. Thus, one possible mechanism by which NOX1 promotes HCC is through STAT3 activation.

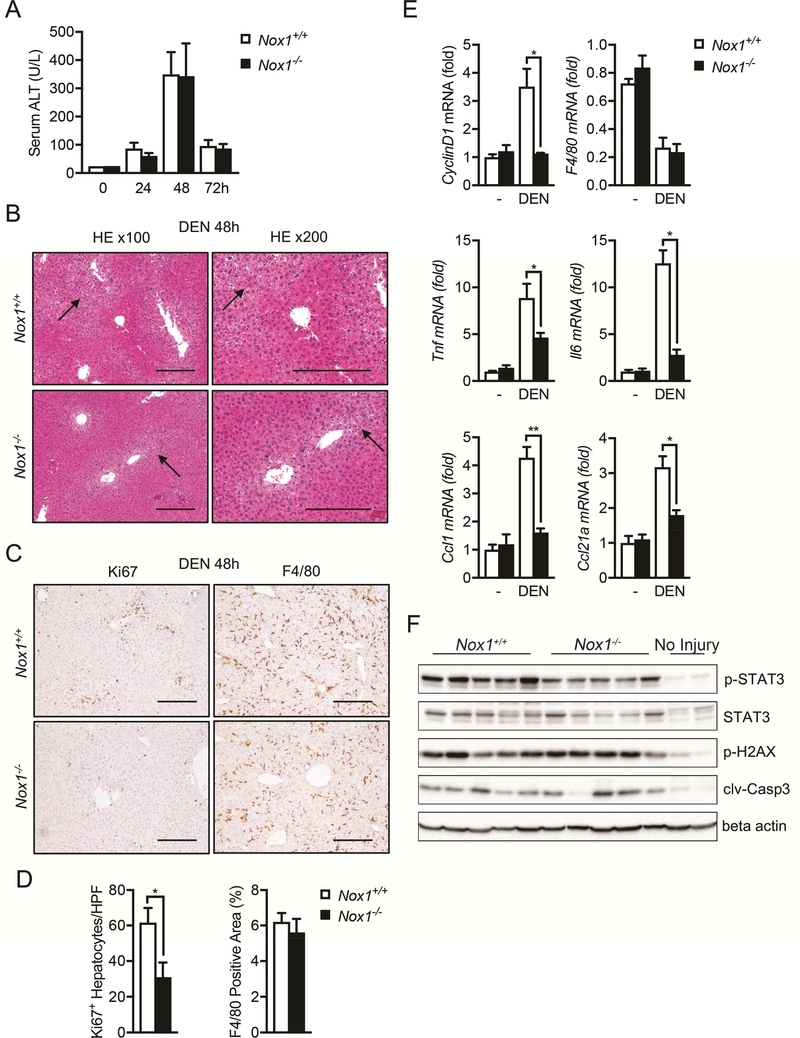

NOX1 promotes liver inflammation and hepatocyte proliferation

DEN is known to trigger hepatocyte DNA damage, cell death responses, inflammation and compensatory proliferation in the liver14. To investigate the impact of NOX1 deficiency on these responses, we i.p. injected 8-week-old Nox1+/+ and Nox1−/− mice with 100 mg/kg DEN. Both Nox1+/+ and Nox1−/− mice exhibited similar elevations of serum ALT 48 hrs after DEN challenge (Figure 3A), which was accompanied by apoptosis/necrosis in the liver (Figure 3B). Although no differences in hepatic damage were observed between two genotypes (Figure 3A), DEN-challenged Nox1−/− mice exhibited less hepatocyte proliferation (Figure 3C and 3D). Consistently, a reduction in CyclinD1 was also detected in the livers of Nox1−/− mice (Figure 3E).

Figure 3. Hepatic inflammation and hepatocyte compensatory proliferation are inhibited in Nox1−/− mice after DEN challenge.

(A) The amounts of alanine transaminase (ALT) present in serum 0, 24, 48 and 72hrs after DEN challenge were quantified (n≧5 mice per group). (B) Representative H&E staining of liver sections 48 hours after DEN injection. Black arrows indicate necrotic areas. (C) Representative liver sections (48 hours after DEN injection) that were immunochemically stained with Ki67 and F4/80. Scale bars: 200 μm. (D) Number of Ki67+ hepatocytes per 20x HPF and percentages of positive staining areas of F4/80 in liver sections from indicated mice 48 hrs after DEN injection (n=5 mice/group). (E) Relative expression of Tnf, Il6, CyclinD1, Ccl21⍺ and F4/80 in liver tissues 48hrs after DEN injection. (F) IB analysis of p-STAT3, STAT3, p-H2AX, cleaved caspase-3 (clv-casp3) and beta actin in the total liver extracts 48hrs post DEN injection. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. Student’s t-test for independent samples and unequal variances was used to assess statistical significance (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001).

Compensatory proliferation after liver damage has been suggested to be mediated by inflammatory cytokines and serves as a main driver for DEN-induced hepatocarcinogenesis14, 15. Among various cytokines induced after DEN administration, IL-6 plays a dominant role in promoting HCC development15. Consistent with this notion, we found that inflammatory cytokines, including TNF and IL-6, was elevated in WT mice after DEN challenge (Figure 3E). In contrast, the NOX1 deficiency attenuated these elevations (Figure 3E). In addition, p-STAT3 was reduced in Nox1−/− livers (Figure 3F), most likely due to reduced IL-6 production (Figure 3E). In contrast, neither DEN-induced DNA damage, as measured by phosphorylation of H2AX (p-H2AX) and subsequent activation of caspase-3 (Clv-casp3), nor the total number of macrophages was affected by NOX1 ablation (Figure 3C-F). As macrophages are the major source of IL-6 in the liver and thereby promote HCC development48, 49, we performed double immunofluorescent staining on DEN-challenged liver sections with antibodies against NOX1 and F4/80. Indeed, a significant number of macrophages expressed NOX1 (Figure S2A), and the induction of NOX1 mRNA by DEN challenge was detected at 24 hours (Figure S2B). Notably, the number of macrophages was reduced at 24 hours but gradually increased at 48 and 72 hours post DEN-challenge (Figure S2B), likely indicating an initial decline of liver resident macrophage population followed by subsequent replenishment of bone marrow-derived macrophage after DEN-induced liver injury.

Production of inflammatory chemokines, such as CCL1 and CCL21a were also reduced in Nox1−/− mice relative to WT controls after DEN challenge (Figure 3E). CCL1 is mainly secreted by monocytes and activated macrophages and attracts monocytes and subsets of T cells50–52, by signaling through its receptor CCR753. In support of this, DEN-challenged Nox1−/− mice had decreased numbers of macrophage (F4/80) and exhibited reduced hepatocyte compensatory proliferation at 8 days post DEN challenge (Figure S2C and S2D).

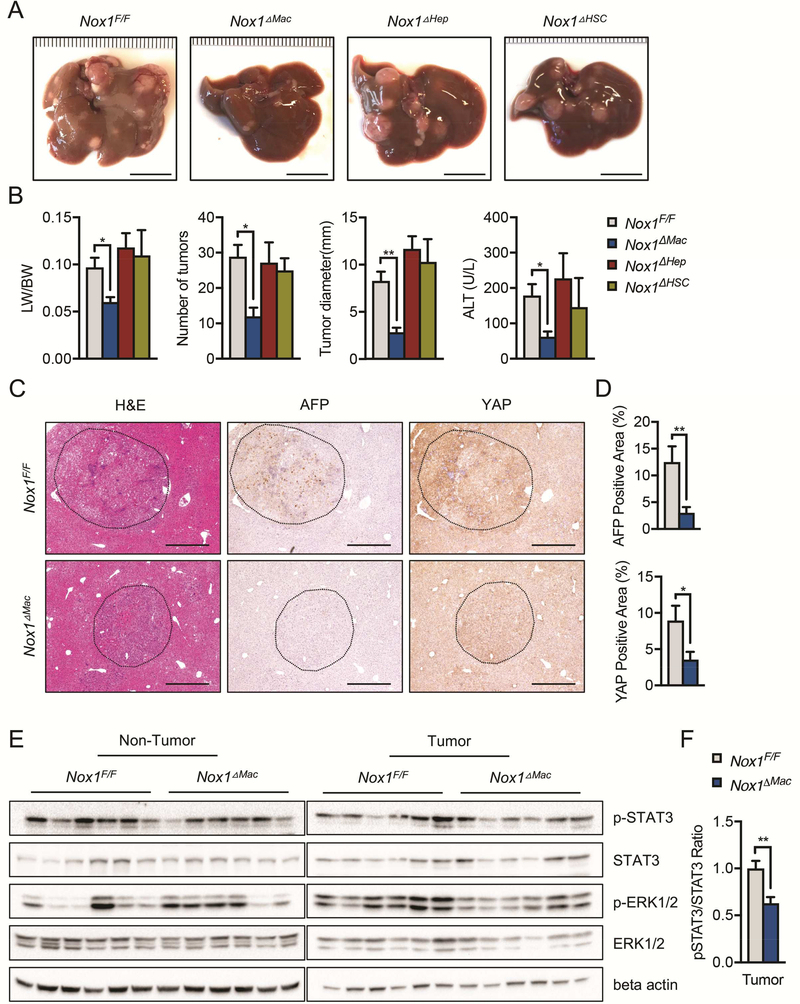

NOX1 in macrophages, but not hepatocytes or HSCs, promotes HCC development

To determine which hepatic cell type contributed to HCC by expressing NOX1, we used cell type specific Cre drivers to delete NOX1 in hepatocytes and bile duct cells (Nox1F/F; Albumin-Cre = Nox1ΔHep), HSCs (Nox1F/F; Lrat-Cre = Nox1ΔHSC) and macrophages (Nox1F/F; LysM-Cre = Nox1ΔMac), respectively. Cell-specific deletion of the gene of interest using these Cre lines was verified by immunostaining with cell-type specific markers (Figure S4). Surprisingly, Nox1ΔHep and Nox1ΔHSC mice developed HCC comparable to Nox1F/F control mice. In contrast, Nox1ΔMac mice displayed significant attenuation in HCC development relative to Nox1F/F mice, comparable to germ line ablated Nox1−/− mice (Figures 4A and 4B). Tumors from Nox1ΔMac mice had reduced AFP and YAP positive staining areas relative to those of the control mice (Figures 4C and 4D). Consistently, mRNA levels of other HCC makers (Afp and Gpc3) as well as markers depicting tumor invasion (Integrinα1 and Integrinβ1) were reduced in Nox1ΔMac liver tumors (Figure S3). Similar to those from Nox1−/− mice, Nox1ΔMac tumors showed decreased p-STAT3 and p-ERK (Figure 4E and 4F), suggesting that NOX1 in macrophages is likely to promote hepatocyte survival and growth through STAT3 and ERK signaling pathways.

Figure 4. Macrophage NOX1 promotes HCC development.

(A) Representative livers from DEN-injected mice of indicated genotypes 9 month after birth (scale bar, 1 cm). (B) Liver weight/body weight (LW/BW) ratios, tumor numbers and maximum sizes of DEN-induced HCCs. Serum ALT amounts in indicated mice were measured by Infinity reagent (n≧6 mice/group). (C) Representative images of liver sections from DEN-injected mice that were stained with H&E, AFP and YAP. (D) Percentages of positive staining areas for AFP and YAP (scale bar, 200 mm) (n=6 mice/group). (E) IB analysis of p-STAT3, STAT3, p-ERK, and ERK in tumor and non-tumor liver tissues from DEN-injected mice. (F) Quantification of relative expression ratio of pSTAT3/STAT3 (n=6 mice/group). Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m.. Student’s t-test for independent samples and unequal variances was used to assess statistical significance (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001).

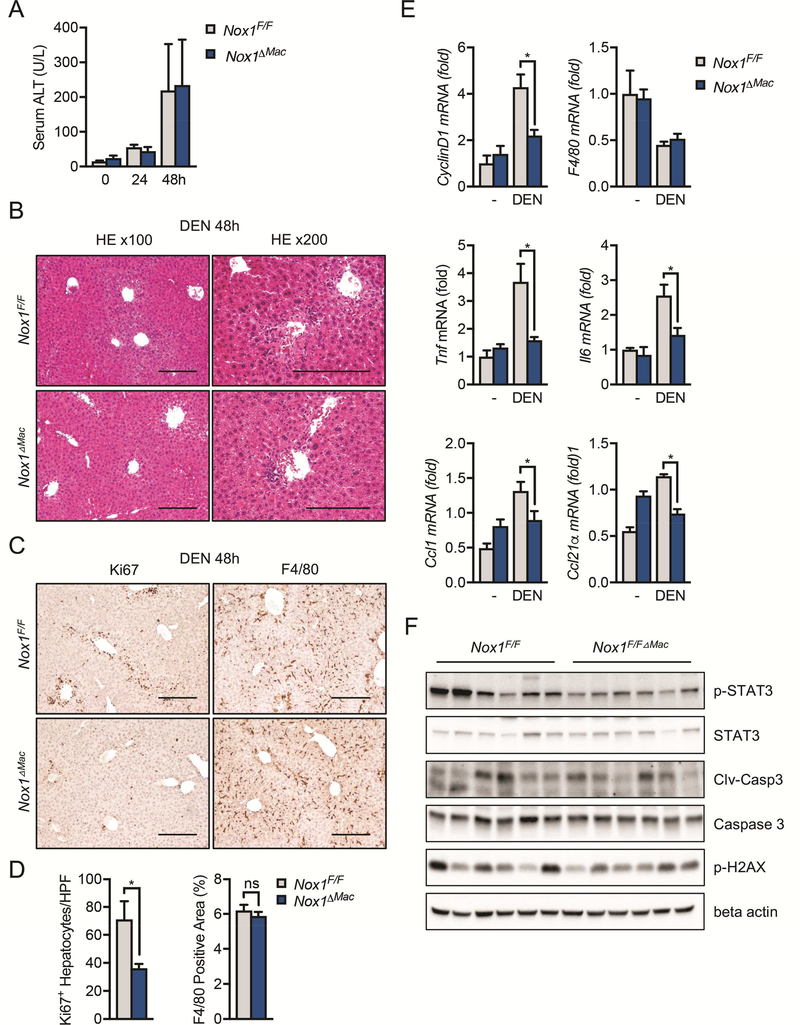

Macrophage NOX1 drives liver inflammation and hepatocyte compensatory proliferation

To further explore the role of NOX1 in liver macrophages, we monitored liver damage, inflammation status and compensatory proliferation at different time points after DEN injection in Nox1F/F and Nox1ΔMac mice. Liver damage as shown by serum ALT or liver histology was similar upon DEN challenge in both Nox1F/F and Nox1ΔMac mice (Figures 5A and 5B). However, hepatocyte Ki67 staining (Figures 5C and 5D) and CyclinD1 expression (Figure 5E) were both reduced in Nox1ΔMac livers, indicating that NOX1 in macrophages stimulates compensatory proliferation of hepatocytes after liver damage induced by DEN. Similar to NOX1 global knockout mice, Nox1ΔMac livers displayed comparable F4/80 positive staining relative to WT control mice (Figures 5C and 5D). Although inflammatory mediators, such as TNF, IL-6, CCL1 and CCL21a were upregulated in livers of Nox1F/F mice after DEN challenge, their expression was substantially reduced in Nox1ΔMac livers (Figure 5E). Lastly, consistent with our results showing that Nox1ΔHep mice had similar HCC formation relative to their WT counterparts, hepatic injury (Figures S5A, S5B and S5F), hepatocyte proliferation (Figures S5C and S5D) and liver inflammation (Figure S5E) were all unaffected by NOX1 specific deletion in hepatocytes and bile duct cells. These results collectively suggest that NOX1 in macrophages promotes hepatic inflammation and hepatocyte proliferation, thereby providing a favorable microenvironment for HCC development.

Figure 5. Hepatic inflammation and hepatocyte compensatory proliferation are reduced in Nox1△Mac mice after DEN challenge.

(A) The amounts of alanine transaminase (ALT) were measured in serum 0, 24, 48hrs post DEN challenge (n≧4 mice/group). (B) Representative H&E staining of liver sections 48 hours post DEN injection. (C) Representative immunohistochemical images of murine liver sections 48 hours after DEN injection. Scale bar: 200 μm. (D) Number of Ki67+ hepatocytes per 20x HPF and percentages of positive staining areas of F4/80 in liver sections from indicated mice 48 hrs after DEN injection (n=6 mice/group). (E) Relative expression of CyclinD1, F4/80, Tnf, Il6, Ccl1 and Ccl21⍺ in the total liver extract 48hrs after DEN injection (n=6 mice/group). (F) IB analysis of p-STAT3, STAT3, p-H2AX, cleaved caspase-3 (clv-casp3) and beta actin in the total liver extract 48hrs after DEN injection. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m.. Student’s t-test for independent samples and unequal variances was used to assess statistical significance (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.0001).

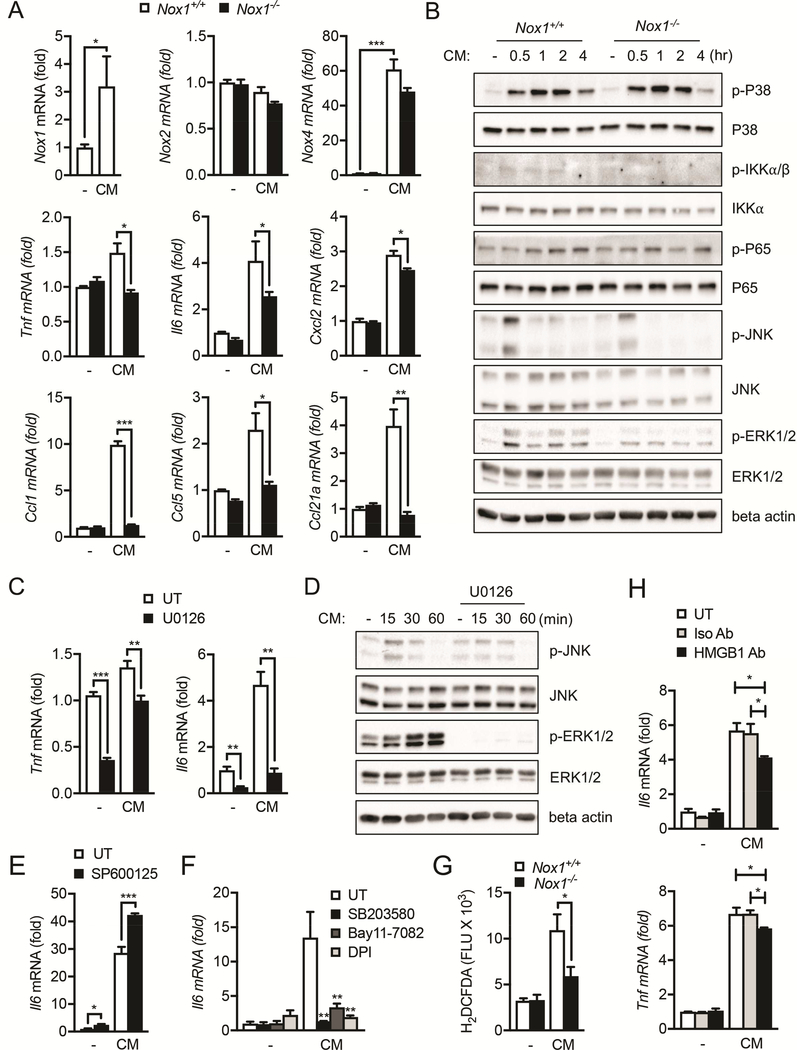

NOX1 is required for macrophage activation by hepatocyte-derived DAMPs

We next investigated the mechanism by which macrophage NOX1 promotes HCC tumorigenesis. Although how hepatocyte death promotes HCC development is still incompletely understood, it has been proposed that necrotic hepatocytes release damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) that activate liver macrophages to produce inflammatory cytokines (e.g. IL-6) that promote compensatory proliferation of hepatocytes15. In particular, IL-6, produced by macrophages upon sensing of DAMPs that are released from necrotic hepatocytes, can stimulate compensatory hepatocyte proliferation via IL-6R-dependent signaling54. Although hepatic IL-6 expression was strongly induced in Nox1F/F mice after DEN injection, it was barely elevated in Nox1ΔMac mice (Figure 5E), suggesting a key role of NOX1 in regulating IL-6 production from macrophages. The expression of other inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, such as TNF, CCL1 and CCL21α, were also reduced in Nox1ΔMac mice after DEN challenge (Figure 5E).

In summary, we found that necrotic hepatocyte-derived conditioned medium (CM) promoted NOX1 expression in cultured macrophages (Figure 6A), and NOX1 was required for macrophage expression of TNF, IL-6 and other inflammatory mediators (Figure 6A). Interestingly, similar to NOX1, we also found that NOX4, but not NOX2, was selectively induced in these BMDMs treated with CM (Figure 6A), suggesting that macrophages may utilize different NOX isoforms when coping with sterile versus microbe-induced inflammation. To further corroborate that DAMPs can induce IL-6 production from macrophages in a NOX1-dependent manner, we demonstrated that ROS production after exposure to CM derived from necrotic hepatocytes, which contains DAMPs, is impaired in Nox1−/− BMDMs relative to that of WT cells (Figure 6G).

Figure 6. Necrotic hepatocyte induces liver macrophage activation via NOX1.

(A) Bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDM) from WT and Nox1−/− mice were incubated with condition medium (CM) from necrotic hepatocytes (lysed by three cycles of freezing and thawing, 5×105 cells per ml) for 4 hours, and cellular RNA was extracted. Relative expression of the indicated genes was determined by quantitative RT-PCR (Q-PCR). (B) IB analysis of indicated target proteins in cell lysate collected from BMDM stimulated with CM from necrotic hepatocytes. (C) BMDMs were pretreated with MEK inhibitor U0126 (10μM) for 30min, and then incubated with CM from necrotic hepatocytes for 4 hours. Relative expression of the indicated genes was determined by Q-PCR. (D) IB analysis of indicated target proteins in cell lysate collected from BMDM pretreated with U0126 and stimulated with CM from necrotic hepatocytes. (E-F) BMDMs were pretreated with JNK inhibitor SP600125 (10μM), p38 inhibitor SB203580 (10μM), IKK inhibitor Bay11–7082 (5μM) or DPI (10μM) for 30min, and then incubated with CM from necrotic hepatocytes for 4 hours. Relative expression of the indicated genes was determined by Q-PCR. (G) BMDM from WT and Nox1−/− mice were incubated with CM from necrotic hepatocytes for 4 hours. Cells were then stained with CM-H2DCFDA, and florescent intensity was quantified. (H) BMDMs were pretreated with isotype control or anti-HMGB1 antibody (2.5ug/ml) for 1h, and then incubated with CM from necrotic hepatocytes for 4 hours. Relative expression of the indicated genes was determined by QPCR. Results are means ± s.e.m. Student’s t-test for independent samples and unequal variances was used to assess statistical significance (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001). Ordinary one-way ANOVA was used to compare between treatment groups to assess statistical significance (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001).

Next, we investigated the signaling pathways that were activated downstream of NOX1. We found that phosphorylation of p38, JNK and ERK1/2 were elevated in WT BMDMs within 4 hrs post CM treatment (Figure 6B). In contrast, ERK1/2 activation was selectively attenuated in Nox1−/− BMDMs (Figure 6B and S6A), whereas p38 MAPK, JNK and NFκB signaling was unaffected (Figure 6B). Consistent with these observations, MEK inhibitor U0126, which inhibits phosphorylation of ERK1/2 while leaving JNK phosphorylation intact (Figure 6D), prevented CM induced expression of TNF and IL-6 (Figure 6C). As expected, pharmacological inhibition of NOX-dependent ROS production by DPI blunted IL-6 expression in macrophages after CM stimulation (Figure 6F). Intriguingly, inhibition of p38, JNK or NFκB signaling in WT BMDMs reduces CM-induced IL-6 expression (Figure 6F), suggesting that other NOX1-indpendent pathways may contribute to their activation after CM stimulation. Together, these results demonstrate that DAMPs released from necrotic hepatocytes induce production of TNF and IL-6 mainly via NOX1dependent pathways.

Although the identity of DAMPs released by necrotic hepatocytes remains to be fully characterized, it has been proposed that high-mobility group box 1 protein (HMGB1) may play a role55, 56. We therefore examined whether HMGB1 contributes to IL-6 production from macrophages that are stimulated with hepatocyte-derived DAMPs. Indeed, pre-incubation of CM with a neutralizing antibody against HMGB1 led to a modest but significant reduction in IL-6 production relative to the isotype control, although TNF levels were largely unaffected (Figure 6H). These results suggest that HMGB1 may contribute to the production of IL-6 by necrotic hepatocytes.

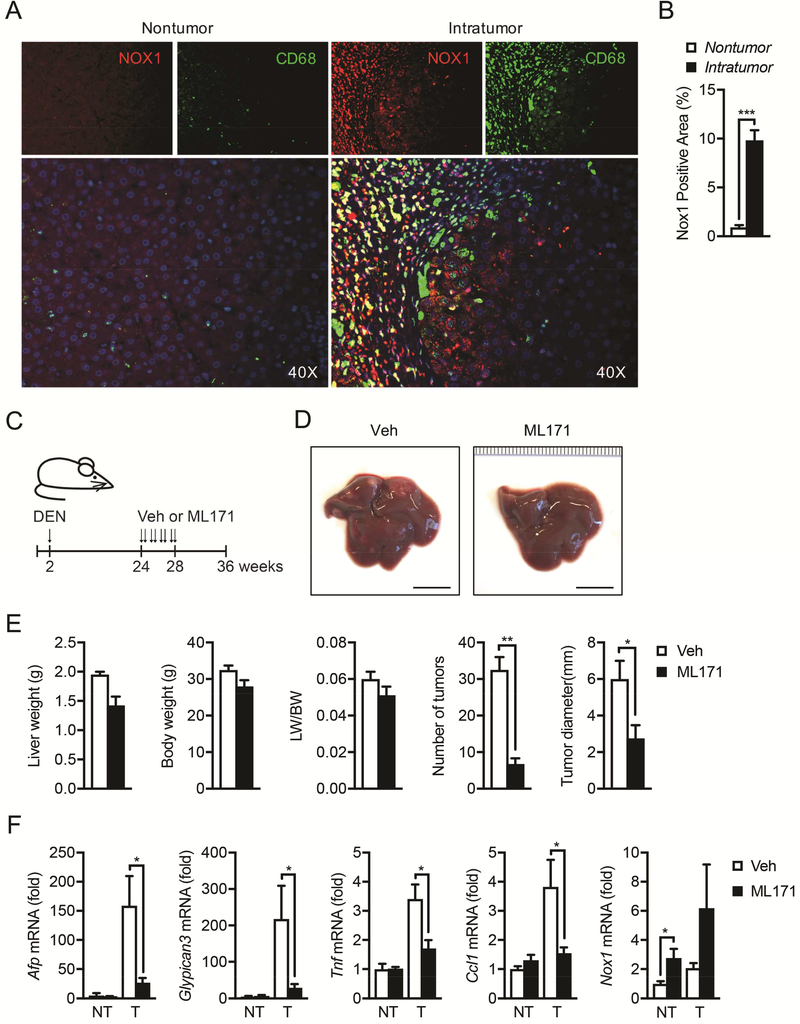

NOX1 is upregulated in TAMs from HCC patients and represents a therapeutic target for HCC

To assess the clinical relevance of NOX1 as seen in our mice results, we assessed NOX1 in human HCC by immunofluorescent staining of patient HCC samples with antibodies against NOX1 and CD68 (a marker of human macrophages). NOX1 expression was dramatically upregulated in human intra-tumor relative to non-tumor regions. Importantly, NOX1 staining areas largely overlaid with macrophage marker CD68 (Figure 7A and 7B), indicating that NOX1 is upregulated in tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) in human HCC.

Figure 7. NOX1 is upregulated in tumor-associated macrophages in HCC patients, and NOX1 represents a therapeutic target for HCC.

(A) NOX1 expression in macrophages from paraffin sections of non-tumoral and intratumoral tissue of HCC patients was analyzed by immunofluorescent microscopy. NOX1, red; CD68, green; DAPI, blue. (B) Quantification of positive staining area of NOX1 in non-tumoral (n=7) and intratumoral (n=10) tissue of HCC patients. (C) Schematic representation of DEN induced HCC model and treatment with NOX1 specific inhibitor (ML171). Two-week-old mice were intraperitoneally injected with DEN (25mg/kg), and ML171 (diluted in PBS at 25μM, 100μl per mouse) was administrated via i.p. twice a week for 4 weeks. Mice were sacrificed at 36 weeks old. (D) Representative livers from DEN-injected mice of indicated treatment group 9 month after birth (scale bar, 1cm). (E) Liver weight/body weight (LW/BW) ratios, tumor numbers and maximum sizes of DEN-induced HCCs (n=4 mice/group). (F) Relative expression of Afp, Gpc3, Tnf, Ccl1 and Nox1 in tumor (T) and non-tumor (NT) tissues from indicated mice was quantified by real-time RT-PCR (n=4 mice/group). Results are means ± s.e.m. Student’s t-test for independent samples and unequal variances was used to assess statistical significance (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001).

Finally, we tested the therapeutic effect of a well-characterized NOX1 specific inhibitor ML17157, 58 on DEN-induced HCC. Firstly, we confirmed that ML171 inhibits CM-induced NOX1-dependent ROS production as well as IL-6 upregulation in BMDMs (Figure S6B and S6C). Remarkably, although ML171 was i.p. administrated (twice per week) to DEN-challenged mice starting at 24 weeks of age (Figure 7C) when HCC pre-neoplastic lesions were already present46 and chronic low-grade inflammation still persisted46, 59 until at least 36 weeks of age (Figure S7), it was able to block HCC development, as shown by a drastic reduction in the total number and maximal size of HCC nodules (Figure 7D and 7E). Consistently, ML171 treatment resulted in the reduced expression of both HCC markers AFP and GPC3 as well as inflammatory mediators (Figure 7F), further suggesting that ML171 suppresses tumor growth by blocking chronic inflammation in the tumor bed.

DISCUSSION

Despite a significant drop in the mortality rate of many types of cancers over the past 2–3 decades, HCC-related death continues to rise60. Accumulating evidence suggests that hepatic inflammation induced upon liver injury drives HCC development by promoting the survival and proliferation of hepatocytes harboring oncogenic mutations. However, little is known regarding the molecular mechanism by which liver inflammation is initiated following liver injury. By taking advantage of combinational approaches, our current study demonstrates that NOX1 is a previously unrecognized initiator of liver inflammation that promotes HCC development.

Earlier studies aiming at dissecting the roles of NOX in liver pathophysiology showed that whole-body NOX1 and NOX4 ablation attenuated hepatocyte apoptosis23 and HSC activation27, 61, 62, thereby decreasing liver fibrosis. Intriguingly, our current results clearly demonstrate that global ablation of NOX1, but not NOX4, inhibited HCC formation in mice. These results are consistent with a recent human HCC genetic marker screening report in which NOX1 expression was shown to correlate with poor prognosis in HCC patients, whereas NOX4 exhibits an opposite effect63. Moreover, in line with a previous study26, our results demonstrate that deficiency in one NOX isoform does not lead to a compensatory increase in other NOX family members (Figure S1), suggesting that different NOX isoforms participate in distinct pathophysiological processes and/or are involved at different stages during liver disease progression.

Of note, Kupffer cells and newly recruited monocyte-derived macrophages are key sensors of liver damage. Upon liver injury, DAMPs released from dying hepatocytes activate liver macrophages to produce inflammatory cytokines (e.g. TNF and IL-6), thereby initiating inflammation. Both TNF and IL-6 were found to positively correlate with HCC progression in humans12 and depletion of either one inhibited HCC development in mice15, 64, 65. However, how the macrophages are activated in response to liver-damaging agents, including DEN, to produce these inflammatory cytokines remains largely undefined. Our current results have bridged this gap not only by identifying a novel mediator (NOX1) of macrophage activation, but also illustrating that an “ROS-MEK” signaling axis that acts downstream to NOX1 is responsible for NOX1-dependent macrophage activation and production of inflammatory cytokines, thereby promoting the survival and proliferation of oncogenic mutation-bearing hepatocytes which ultimately give rise to HCC.

Although our results suggest a role of HMGB1 as a candidate hepatocyte-derived DAMP that induces macrophage activation, the complete spectrum of DAMPs that are released from dying hepatocytes upon liver injury remains to be investigated, especially considering the fact that neutralizing HMGB1 results in only a modest decrease in IL-6 and TNF. Most likely other DAMPs, such as ATP, uric acid, oxidized mtDNA and lipids, also contribute to macrophage activation by injured hepatocytes66. Some of these DAMPs may directly engage Toll-like receptors to induce TNF and IL-6, whereas others might activate NLRP3 (Nod-like receptor pyrin domain containing 3) inflammasome to produce biologically active IL-1β that in turn upregulates TNF and IL-666, 67. Nonetheless, given the fact that multiple DAMPs can compensate each other’s inflammation promoting activity and hepatic inflammation can become complicated by the presence of microbial products resulting from increased intestinal permeability in HCC patients, the concept of targeting a single DAMP to prevent liver tumorigenesis may therefore need to be revisited. Nonetheless, our current study has provided an alternative therapeutic approach to HCC prevention, which is to block NOX1 activity, such as by using a highly specific and potent small molecule inhibitor, ML171. A continuous 4-week treatment scheme starting at the 24th week after birth is sufficient to deliver a remarkable inhibition of HCC development in DEN-challenged mice. Consistence with what we have observed in mice, our results demonstrate that NOX1 is also significantly upregulated in liver macrophages from HCC patients, which raises the possibility of targeting NOX1 to treat human liver cancer.

DEN generates ROS that results in DNA damage, mutations, and cancer68, 69. However, our study demonstrates that DEN induces equal amount of DNA damage in the livers of Nox1−/− and WT mice (as measured by p-H2AX), but Nox1−/− mice have less HCC. Furthermore, pharmacological inhibition of NOX1 after HCC induction was sufficient to inhibit HCC formation. Taken together, our study demonstrates that a second mechanism of action of ROS in the pathogenesis of DEN-induced HCC is to generate hepatocyte injury, hepatocyte death, inflammation, and compensatory hepatocyte proliferation. Our study also shows that macrophage-derived ROS are unlikely to cause direct damage to hepatocyte, a conclusion that is entirely consistent with the high reactivity and short half-life of ROS.

In summary, we have identified and mechanistically characterized a novel liver inflammation initiator, NOX1 that links ROS production with liver inflammation, oncogene-harboring mutant hepatocyte proliferation and HCC development. We have demonstrated that genetic or pharmacological inhibition of NOX1 decrease HCC, thus establishing a solid basis for evaluating NOX1 inhibitors as adjuvant therapy for human HCC.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We thank Dennis R. Petersen and Kevin J. Tracey for providing us with antibody against 4-HNE and HMGB1, respectively. Z.Z. was supported by a Prevent Cancer Foundation Board of Directors Award and an American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) Pinnacle Research Award. D.D. was supported by the American Liver Foundation (ALF) Liver Scholar Award. Research was supported by grants from the NIH (R01AI043477, R01CA211794 and R01CA198103) to M.K..

Grant support: Supported by the National Institutes of Health R01 DK101737-01A1, U01 AA022614-01A1, R01 DK099205-01A1, P50 AA011999 (T.K. and D.A.B.)

Abbreviations:

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- NOX

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- DEN

diethylnitrosamine

- AFP

α fetoprotein

- YAP

Yes-associated protein

- GPC3

Glypican 3

- VEGFR

vascular endothelial growth factor receptor

- PECAM-1

platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- IL-1β

interleukin-1β

- IL-6

interleukin-6

- 4-HNE

4-Hydroxynonenal

- HSC

hepatic stellate cells

- DAMP

damage-associated molecular pattern

- BMDM

bone marrow derived macrophage

Footnotes

Disclosures:

The authors disclose no conflicts.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCE

- 1.Ahmed F, Perz JF, Kwong S, et al. National trends and disparities in the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma, 1998–2003. Prev Chronic Dis 2008;5:A74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruno S, Silini E, Crosignani A, et al. Hepatitis C virus genotypes and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: a prospective study. Hepatology 1997;25:754–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trichopoulos D, Bamia C, Lagiou P, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma risk factors and disease burden in a European cohort: a nested case-control study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2011;103:1686–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Regimbeau JM, Colombat M, Mognol P, et al. Obesity and diabetes as a risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl 2004;10:S69–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karagozian R, Derdak Z, Baffy G. Obesity-associated mechanisms of hepatocarcinogenesis. Metabolism 2014;63:607–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Polesel J, Zucchetto A, Montella M, et al. The impact of obesity and diabetes mellitus on the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Oncol 2009;20:353–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Welzel TM, Graubard BI, Zeuzem S, et al. Metabolic syndrome increases the risk of primary liver cancer in the United States: a study in the SEER-Medicare database. Hepatology 2011;54:463–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun B, Karin M. Obesity, inflammation, and liver cancer. J Hepatol 2012;56:704–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Llovet JM, Villanueva A, Lachenmayer A, et al. Advances in targeted therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma in the genomic era. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2015;12:408–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karin M, Clevers H. Reparative inflammation takes charge of tissue regeneration. Nature 2016;529:307–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fausto N Mouse liver tumorigenesis: models, mechanisms, and relevance to human disease. Semin Liver Dis 1999;19:243–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong VW, Yu J, Cheng AS, et al. High serum interleukin-6 level predicts future hepatocellular carcinoma development in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Int J Cancer 2009;124:2766–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakagawa H, Maeda S, Yoshida H, et al. Serum IL-6 levels and the risk for hepatocarcinogenesis in chronic hepatitis C patients: an analysis based on gender differences. Int J Cancer 2009;125:2264–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maeda S, Kamata H, Luo JL, et al. IKKbeta couples hepatocyte death to cytokine-driven compensatory proliferation that promotes chemical hepatocarcinogenesis. Cell 2005;121:977–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naugler WE, Sakurai T, Kim S, et al. Gender disparity in liver cancer due to sex differences in MyD88-dependent IL-6 production. Science 2007;317:121–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun B, Karin M. Inflammation and liver tumorigenesis. Front Med 2013;7:242–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang JX, Torok NJ. NADPH Oxidases in Chronic Liver Diseases. Adv Hepatol 2014;2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liang S, Kisseleva T, Brenner DA. The Role of NADPH Oxidases (NOXs) in Liver Fibrosis and the Activation of Myofibroblasts. Front Physiol 2016;7:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bedard K, Krause KH. The NOX family of ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev 2007;87:245–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lambeth JD. NOX enzymes and the biology of reactive oxygen. Nat Rev Immunol 2004;4:181–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paik YH, Kim J, Aoyama T, et al. Role of NADPH oxidases in liver fibrosis. Antioxid Redox Signal 2014;20:2854–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Mochel NS, Seronello S, Wang SH, et al. Hepatocyte NAD(P)H oxidases as an endogenous source of reactive oxygen species during hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology 2010;52:47–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kono H, Rusyn I, Yin M, et al. NADPH oxidase-derived free radicals are key oxidants in alcoholinduced liver disease. J Clin Invest 2000;106:867–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reinehr R, Becker S, Keitel V, et al. Bile salt-induced apoptosis involves NADPH oxidase isoform activation. Gastroenterology 2005;129:2009–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Minicis S, Seki E, Paik YH, et al. Role and cellular source of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase in hepatic fibrosis. Hepatology 2010;52:1420–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aoyama T, Paik YH, Watanabe S, et al. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase in experimental liver fibrosis: GKT137831 as a novel potential therapeutic agent. Hepatology 2012;56:2316–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang JX, Chen X, Serizawa N, et al. Liver fibrosis and hepatocyte apoptosis are attenuated by GKT137831, a novel NOX4/NOX1 inhibitor in vivo. Free Radic Biol Med 2012;53:289–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bettaieb A, Jiang JX, Sasaki Y, et al. Hepatocyte Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate Reduced Oxidase 4 Regulates Stress Signaling, Fibrosis, and Insulin Sensitivity During Development of Steatohepatitis in Mice. Gastroenterology 2015;149:468–80 e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garcia-Ruiz I, Solis-Munoz P, Fernandez-Moreira D, et al. NADPH oxidase is implicated in the pathogenesis of oxidative phosphorylation dysfunction in mice fed a high-fat diet. Sci Rep 2016;6:23664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu CL, Qiu JL, Huang PZ, et al. NADPH oxidase DUOX1 and DUOX2 but not NOX4 are independent predictors in hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatectomy. Tumour Biol 2011;32:1173–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tolba R, Kraus T, Liedtke C, et al. Diethylnitrosamine (DEN)-induced carcinogenic liver injury in mice. Lab Anim 2015;49:59–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kang JS, Wanibuchi H, Morimura K, et al. Role of CYP2E1 in diethylnitrosamine-induced hepatocarcinogenesis in vivo. Cancer Res 2007;67:11141–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.He G, Karin M. NF-kappaB and STAT3 - key players in liver inflammation and cancer. Cell Res 2011;21:159–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garrido-Urbani S, Jemelin S, Deffert C, et al. Targeting vascular NADPH oxidase 1 blocks tumor angiogenesis through a PPARalpha mediated mechanism. PLoS One 2011;6:e14665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leoni G, Alam A, Neumann PA, et al. Annexin A1, formyl peptide receptor, and NOX1 orchestrate epithelial repair. J Clin Invest 2013;123:443–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mederacke I, Hsu CC, Troeger JS, et al. Fate tracing reveals hepatic stellate cells as dominant contributors to liver fibrosis independent of its aetiology. Nat Commun 2013;4:2823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hornung V, Bauernfeind F, Halle A, et al. Silica crystals and aluminum salts activate the NALP3 inflammasome through phagosomal destabilization. Nat Immunol 2008;9:847–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Han SX, Bai E, Jin GH, et al. Expression and clinical significance of YAP, TAZ, and AREG in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Immunol Res 2014;2014:261365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hirose Y, Naito Z, Kato S, et al. Immunohistochemical study of CYP2E1 in hepatocellular carcinoma carcinogenesis: examination with newly prepared anti-human CYP2E1 antibody. J Nippon Med Sch 2002;69:243–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ho JC, Cheung ST, Leung KL, et al. Decreased expression of cytochrome P450 2E1 is associated with poor prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Cancer 2004;111:494–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hirano T, Ishihara K, Hibi M. Roles of STAT3 in mediating the cell growth, differentiation and survival signals relayed through the IL-6 family of cytokine receptors. Oncogene 2000;19:2548–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takeda K, Akira S. STAT family of transcription factors in cytokine-mediated biological responses. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2000;11:199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Al Zaid Siddiquee K, Turkson J. STAT3 as a target for inducing apoptosis in solid and hematological tumors. Cell Res 2008;18:254–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taniguchi K, Karin M. NF-kappaB, inflammation, immunity and cancer: coming of age. Nat Rev Immunol 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Calvisi DF, Ladu S, Gorden A, et al. Ubiquitous activation of Ras and Jak/Stat pathways in human HCC. Gastroenterology 2006;130:1117–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.He G, Dhar D, Nakagawa H, et al. Identification of liver cancer progenitors whose malignant progression depends on autocrine IL-6 signaling. Cell 2013;155:384–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.He G, Yu GY, Temkin V, et al. Hepatocyte IKKbeta/NF-kappaB inhibits tumor promotion and progression by preventing oxidative stress-driven STAT3 activation. Cancer Cell 2010;17:286–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baumann H, Gauldie J. The acute phase response. Immunol Today 1994;15:74–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gabay C, Kushner I. Acute-phase proteins and other systemic responses to inflammation. N Engl J Med 1999;340:448–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Iellem A, Mariani M, Lang R, et al. Unique chemotactic response profile and specific expression of chemokine receptors CCR4 and CCR8 by CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells. J Exp Med 2001;194:847–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miller MD, Krangel MS. The human cytokine I-309 is a monocyte chemoattractant. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1992;89:2950–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zingoni A, Soto H, Hedrick JA, et al. The chemokine receptor CCR8 is preferentially expressed in Th2 but not Th1 cells. J Immunol 1998;161:547–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Paradis A, Bernier S, Dumais N. TLR4 induces CCR7-dependent monocytes transmigration through the blood-brain barrier. J Neuroimmunol 2016;295–296: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell 2010;140:883–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Scaffidi P, Misteli T, Bianchi ME. Release of chromatin protein HMGB1 by necrotic cells triggers inflammation. Nature 2002;418:191–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang H, Li W, Goldstein R, et al. HMGB1 as a potential therapeutic target. Novartis Found Symp 2007;280:73–85; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Altenhofer S, Radermacher KA, Kleikers PW, et al. Evolution of NADPH Oxidase Inhibitors: Selectivity and Mechanisms for Target Engagement. Antioxid Redox Signal 2015;23:406–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gianni D, Taulet N, Zhang H, et al. A novel and specific NADPH oxidase-1 (Nox1) small-molecule inhibitor blocks the formation of functional invadopodia in human colon cancer cells. ACS Chem Biol 2010;5:981–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li C, Deng M, Hu J, et al. Chronic inflammation contributes to the development of hepatocellular carcinoma by decreasing miR-122 levels. Oncotarget 2016;7:17021–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Llovet JM, Villanueva A, Lachenmayer A, et al. Advances in targeted therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma in the genomic era. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2015;12:436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cui W, Matsuno K, Iwata K, et al. NOX1/nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate, reduced form (NADPH) oxidase promotes proliferation of stellate cells and aggravates liver fibrosis induced by bile duct ligation. Hepatology 2011;54:949–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lan T, Kisseleva T, Brenner DA. Deficiency of NOX1 or NOX4 Prevents Liver Inflammation and Fibrosis in Mice through Inhibition of Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation. PLoS One 2015;10:e0129743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ha SY, Paik YH, Yang JW, et al. NADPH Oxidase 1 and NADPH Oxidase 4 Have Opposite Prognostic Effects for Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma after Hepatectomy. Gut Liver 2016;10:826–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Knight B, Yeoh GC, Husk KL, et al. Impaired preneoplastic changes and liver tumor formation in tumor necrosis factor receptor type 1 knockout mice. J Exp Med 2000;192:1809–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Park EJ, Lee JH, Yu GY, et al. Dietary and genetic obesity promote liver inflammation and tumorigenesis by enhancing IL-6 and TNF expression. Cell 2010;140:197–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhong Z, Sanchez-Lopez E, Karin M. Autophagy, Inflammation, and Immunity: A Troika Governing Cancer and Its Treatment. Cell 2016;166:288–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Afonina IS, Zhong Z, Karin M, et al. Limiting inflammation-the negative regulation of NF-kappaB and the NLRP3 inflammasome. Nat Immunol 2017;18:861–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Enriquez-Cortina C, Bello-Monroy O, Rosales-Cruz P, et al. Cholesterol overload in the liver aggravates oxidative stress-mediated DNA damage and accelerates hepatocarcinogenesis. Oncotarget 2017;8:104136–104148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Teufelhofer O, Parzefall W, Kainzbauer E, et al. Superoxide generation from Kupffer cells contributes to hepatocarcinogenesis: studies on NADPH oxidase knockout mice. Carcinogenesis 2005;26:319–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.