Abstract

In the present study, we characterized bacteriocin BaCf3, isolated and purified from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens BTSS3, and demonstrated its inhibitory potential on growth and biofilm formation of certain food spoilage bacteria and pathogens. Purification was by gel filtration chromatography and its molecular weight was 3028.422 Da after MALDI-TOF MS. The bacteriocin was highly thermostable withstanding even autoclaving conditions and pH tolerant (2.0–13.0). The bacteriocin was sensitive to oxidizing agent (DMSO) and reducing agent (DTT). The de novo sequence of the bacteriocin BaCf3 was identified and was found to be novel. The sequence analysis shows the presence of a disulphide linkage between C6 and C13. The microtitre plate assay proved that BaCf3 could reduce up to 80% biofilm produced by strong biofilm producers from food samples. In addition, BaCf3 did not show cytotoxicity on 3-TL3 cell line.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13205-019-1639-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Bacteriocin, Bacillus, MALDI-TOF, Biofilm, Cytotoxicity

Introduction

Food-borne diseases and contaminated food are chief concern to humankind. Though the type and severity of food-borne diseases have changed through years, it is still an issue in all nations. According to WHO, almost 1 in 10 people in the world fall ill and 420,000 die every year (WHO 2015) due to food contamination. Bacterial biofilms are one of the major causes of food contamination. Biofilm formation imparts antibiotic resistance to the pathogens leading to complications. This difficulty in successful treatment of biofilm-associated infections calls for the hunt of novel compounds and technologies for biofilm eradication. Many natural products like antimicrobial peptides and bacteriocins have been successfully used as antibiofilm agents in food preservation and medicine (Spizek et al. 2010).

Biofilms are irreversible assemblage of surface-associated microbial cells enclosed in an extracellular polymeric matrix substance. According to Costerton et al. (1987) a biofilm is a functional consortium of microorganisms attached to a surface and is embedded in extracellular polymeric substances (EPS). They are difficult to eradicate completely, as they are often resistant to normal sanitation procedures that can result in detrimental processes. Even when a food surface appears to be clean, there is the possible presence of biofilm, a potential hazard that needs elimination. An antibiofilm drug can either facilitate the dispersion of preformed biofilms or inhibit the formation of new biofilms in vivo. The biopreservative effect of sonorensin-coated film in chicken meat and tomato samples by inhibiting spoilage bacteria, demonstrated the potential of sonorensin as an alternative to current antibiotics/ preservatives (Chopra et al. 2015). Antimicrobial protein from a Citrobacter freundii strain ATCC 43864 named ColA-43864 exhibited inhibitory activity against species from several genera of Gram-negative bacteria including K. pneumonia and Escherichia coli and was effective against biofilms (Shanks et al. 2012). Costa et al. (2018) reported the antimicrobial and antibiofilm potentials of BLS P34 produced by Bacillus sp. P34.

In the current study, bacteriocin BaCf3 produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens BTSS3 isolated from the gut of deep-sea shark was characterized for its physical properties and examined for antibiofilm potential. A non-toxicity study was also conducted on mouse 3T3-L1 cell line.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and production of bacteriocin

Bacillus amyloliquefaciens BTSS3 (MCC 2981), the bacteriocin producing strain isolated from the gut of deep-sea shark, Centroscyllium fabricii (Bindiya et al. 2015)and biofilm producers isolated from various food samples (Laxmi and Sarita 2014) were used in this study. Bacillus circulans NCIM No. 2107 was used as the indicator strain in antimicrobial activity assays as described in our previous study (Bindiya et al. 2015). The stock cultures were maintained at − 70 °C in nutrient broth (Himedia, Mumbai, India) containing 30% (v/v) glycerol. The optimized minimal medium (M9) used for production of BaCf3 consisted of 0.6 g Na2HPO4, 0.3 g KH2PO4, 3 g NaCl, 0.5 g Tryptone, 1 g inositol, 4 mM MgSO4 and 200 µM CaCl2 (Optimized for BaC3 production, Unpublished data). All the media components were purchased from Himedia and Merck (India). The bacteria B. amyloliquefaciens BTSS3 and B. circulans NCIM 2107 were maintained on Zobell and Nutrient agar (Himedia) slants respectively.

Quantitative estimation of antibacterial titres by critical dilution assay

Serial twofold dilutions were made from cell-free supernatants (CFS) of the culture. From each dilution, 5 µL was spotted on an indicator strain, which was swab-inoculated on Mueller-Hinton Agar plate. The plates were incubated at the optimum growth temperature of the indicator strain. The bacteriocin activity was expressed in activity units per mL (AU/mL). One arbitrary unit (AU) of bacteriocin was defined as 5 µL of the highest dilution yielding a zone of growth inhibition on the indicator lawn (Mayr-Harting et al. 1972). The reciprocal of the highest dilution was multiplied by 200 (1 mL/5 µL) to obtain activity units per mL (AU/mL) (Enan et al. 1996).

Purification and de novo sequencing of bacteriocin BaCf3

The overnight culture (18 h) prepared with 2% inoculums and incubated at 40 °C with aeration 150 rpm was centrifuged at 16,128g for 10 min at 4 °C to obtain the cell-free supernatant (cfs). To the cfs thus obtained ammonium sulphate (Merck) was added to obtain 30% (w/v) saturation (Heyns and De Moor 1971) and centrifuged. The precipitate obtained was dissolved in 10 mM phosphate buffer and dialyzed using 2 kDa benzoylated dialysis tubing (Sigma Aldrich, USA) against 0.01 M phosphate buffer of pH 7.4 at 4 °C with six changes of buffer (10 mM phosphate buffer) every 6 h in ratio 1:1000.

Concentrated fraction obtained from ammonium sulphate precipitation was subjected to size-exclusion chromatography on Sephadex G-50 (Sigma Aldrich) using a 1.5 × 50 cm glass Econocolumn (Biorad). The column was equilibrated and eluted with 0.01 M phosphate buffer, pH 7. The absorbance at 280 nm was monitored and 2 mL fractions were collected. Each fraction was assayed for bacteriocin activity. Fractions demonstrating inhibitory activity against B. circulans NCIM 2107 were pooled and concentrated by lyophilization. Concentrated pooled active fractions were resuspended and analyzed using an Ultraflex MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Germany).

The partially purified protein after dialysis was run in duplicates on glycine SDS-PAGE using 15% resolving gel (Laemmli 1970), along with protein molecular weight marker (Merck-GeNei, India) in a minigel electrophoresis system (BioRad, USA) at 80 V; and the gel cut vertically into two. One-half containing the sample and molecular weight marker was stained, while the other with sample alone was washed thrice with 0.01% Tween 80 (30 min each), followed by washing with deionized water to remove SDS. This gel piece was then placed in a sterile petri-plate, overlaid with soft Mueller-Hinton agar (0.8% agar) inoculated with 100 µL culture (OD600 = 1) of B. circulans, and observed after an overnight incubation at 37 °C to detect inhibition zone at the position of bacteriocin on the gel (Yamamoto et al. 2003).

The single band obtained from SDS PAGE was excised and digested with trypsin (Shevchenko et al. 2007). The peptides were co-crystallized with α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid matrix on the target plate (384-well ground steel plate, Bruker Daltonics, Germany) and external peptide mass calibration was applied (Peptide mixture 1) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. The MS/MS data of selected trypsin-digested fragments were analysed by mMass 5.5.0 (Niedermeyer and Strohalm 2012). The sequence of the peptide fragments was derived manually from the ‘a’, ‘b’ and ‘y’ fragments and hence the corresponding amino acids from their molecular mass (Wilson and Walker 2000). The derived fragments were analysed in fragment ion calculator server from The Institute for Systems Biology at http://db.systemsbiology.net:8080/proteomicsToolkit/.

Characterization of bacteriocin BaCf3

To evaluate heat stability, bacteriocin (Activity = 12,800 AU/mL) was exposed to temperatures ranging from 40 to 100 °C for 1 h and121 °C per 105 kPa for 15 min. To study the effect of different pH, equal volume of bacteriocin (Activity = 512,000 AU/mL) was added to buffers with pH range 1–12 and kept for18 h at 4 °C. The buffer systems used included hydrochloric acid/potassium chloride buffer (pH 1–2), citric acid/sodium citrate buffer (pH 3–5), phosphate buffer (pH 6–7), Tris aminomethane/hydrochloric acid buffer (pH 8–9), sodium bicarbonate/sodium hydroxide buffer (pH 10), sodium phosphate dibasic/sodium hydroxide buffer (pH 11–12) (Vincent and John 2009). Equal volumes of 1 mM solutions of Na2+, Ca2+, Mg2+, Ba2+, Co2+, Cu2+, Mn2+, Zn2+, Fe3+, Al3+ and purified bacteriocin (Activity = 512,000 AU/mL) were mixed and incubated at 4 °C for 1 h. The untreated sample served as control. To examine the effect of oxidizing and reducing agents on bacteriocin activity 50 and 100 mM of DTT, β-mercaptoethanol and DMSO were prepared. Equal volume of purified bacteriocin samples (Activity = 512,000 AU/mL) were mixed with these oxidizing/reducing agents and incubated for 1 h. The treated samples were tested for residual antimicrobial activity against the test organisms. 50 and 100 mM of DTT, β-mercaptoethanol and DMSO were used as negative control in bacteriocin assay.

Microtitre plate assay

Biofilm producers Bacillus altitudinis BTMW1, Pseudomonas aeruginosa BTRY1, Bacillus sp. SD1, Bacillus licheniformis SD2, Brevibacterium cassie DF1, Staphylococcus warnie DF2, Bacillus niacini DP3, Micrococcus luteus FF1 and Geobacillus stearothermophilus FF2 isolated from various food sources were used for the study of combined inhibitory activity on bacterial growth and biofilm formation of bacteriocin BaCf3 (Laxmi and Sarita 2014). Inhibitory activity of the bacteriocin was also studied on some standard food pathogens namely E. coli (NCIM 2343), Salmonella Typhimurium (NCIM 2501), Enterococcus faecalis (ATCC 29212) and Clostridium perfringens (NCIM 2677). The assay was conducted in 96 well microtitre plates using a modified method of Jackson et al. (2002). The attached biofilm was fixed with methanol for 15 min and air dried. Wells were then stained with 1% crystal violet; excess stain was removed by rinsing under running tap water and air dried. The dye bound to the adsorbed biofilm was extracted using 33% (v/v) glacial acetic acid and absorbance was measured at 570 nm in BioSpectrometer (Eppendorf, India). For each experiment, background staining was corrected by subtracting the crystal violet bound to uninoculated controls.

Percentage reduction in biofilm formation was calculated as (Chaieb et al. 2011):

Biofilm inhibitory concentration (BIC) can be defined as the lowest concentration of the compound which inhibits biofilm formation. Bacteriocin with an initial concentration of 100 µg/mL was serially diluted in microtitre plate and the biofilm producers at OD600 = 1 were added. The dilution without visible biofilm formation was considered as its BIC (Chaieb et al. 2011). BIC of BaCf3 was calculated for each biofilm producer tested.

Cytotoxicity assay

3T3-L1, (from National Centre for Cell Science, Pune, India) a cell line derived from mouse 3T3 cells with a fibroblast-like morphology was used in cytotoxicity studies using different concentrations of bacteriocins (40, 80, 120, 160, 200 µg/mL) for 24 h, 48 h and 72 h. Cell death was then tested by MTT assay (Alley et al. 1988).

Cytotoxicity of the compound on the cells was calculated as cell growth inhibition (IR).

where,

Statistical analysis

The data was analyzed by Microsoft Excel 2010 and all the graphs were plotted by Graphpad Prism 6.0. All the assays were conducted in triplicates. ANOVA was calculated for antibiofilm and cytotoxicity assays.

Results and discussion

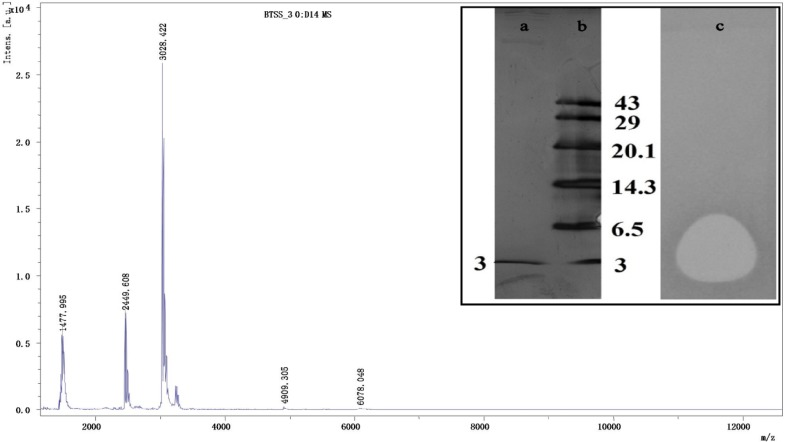

The bacteriocin BaCf3was precipitated from cell-free supernatant by 30% ammonium sulphate saturation. SDS-PAGE and zymogram showed the molecular weight of the bacteriocin was between 3 and 6.5 kDa (Fig. 1). Further purification by gel filtration chromatography in a single band corresponding to 3 kDa was observed on SDS PAGE, demonstrating the purity of the biomolecule. MALDI-TOF mass spectroscopy showed a molecular weight of 3028.422 Da (Fig. 1). The molecular weights of many bacteriocins were identified by MALDI TOF MS. Subtilosin A1 has a molecular mass of 3412.5 Da as revealed by MALDI MS analysis (Sebei et al. 2007). Cerein MRX1 was a heat-stable bacteriocin detected in a B. cereus isolate from water plant roots (Lewus et al. 1991). It had a molecular mass of 3137.93 Da (according to MALDI-TOF MS analysis) and was capable of withstanding exposure to a wide range of pH values. MALDI-TOF analysis of bacteriocin from Weissella confusa A3 of dairy origin gave a mass of 2.7 kDa (Goh and Philip 2015). From the literature, it was noted that Class II bacteriocins of Gram-positive bacteria are < 10 kDa in size. From the MS/MS pattern it was clear that trypsin digested the proteins in to seven fragments such as 1173, 1304, 1640, 2451, 2474, 2632, 2654 (Supplementary data, Fig. 1). From the MS/MS pattern of 1173 (Supplementary data, Fig. 2) and 1304 (Supplementary data Fig. 3) the peptide sequences were derived by manual calculation (Hunt et al. 2007).

Fig. 1.

MALDI-TOF MS of BaCf3. Inset is the SDS PAGE and in-gel activity of BaCf3. Lane a: Purified BaCf3, Lane b: Low Range Peptide marker (GeNei). Lane c: In-gel activity analysis

The amino acid sequence of BaCf3 was derived as GNHDCCMGQLPKCMLGPGQ GAATXQGK. We could not find any match in protein BLAST showing its novelty. MALDI-TOF MS/MS was used for partial sequencing of acidocin D20079 (Deraz et al. 2005). The sequence analysis indicates the presence of a disulphide linkage between C6 and C13.

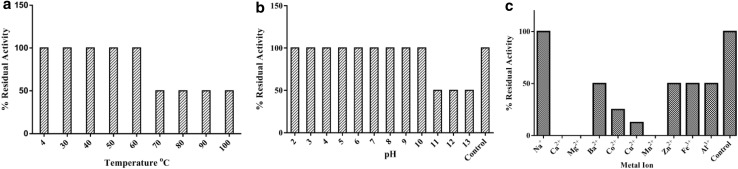

Bacteriocin BaCf3 retained 100% of its activity even after treatment at 121 °C for 15 min proving that it is highly thermostable even though a prolonged treatment at 70 °C to 100 °C for 1 h reduced its activity to 50% (Fig. 2a). The bacteriocin activity was also retained over a broad range of pH (2.0–13.0) with a reduction of activity to 50% in pH range 11–13 (Fig. 2b). BaCf3 was stable at all the pH tested, suggesting suitability for applications in acid and alkaline conditions.

Fig. 2.

Effect of a temperature b pH and c metal ions on BaCf3. The activity was calculated by twofold dilution method hence the decrease in values is in a stepwise response (twofold reduction in activity)

Antibacterial activity of BaCf3 was nullified by the addition of Ca2+, Mg2+ and Mn2+ salts. Ba2+, Co2+, Cu2+, Zn2+, Fe3+ and Al3+ also diminished the activity of BaCf3 (Fig. 2c). The metal ions disturb salt bridges of proteins, thereby destabilizing and precipitating them. Many metal ions can chelate amino acids of the bacteriocins and cause conformation changes. The effect of metal ions on bacteriocins are least studied, but their effect on enzymes and other biological peptides are well known.

The activity of BaCf3 was significantly reduced due to the treatment with an oxidising agent like DMSO and reducing agents such as β-mercaptoethanol and DTT (Table 1). The loss of activity by treatment with mild oxidizing agent DMSO also indicates the presence of oxidation labile disulphide linkages (Papanyan and Markaryan 2013). The fact that a higher concentration (100 mM) of DTT caused complete loss of activity points to the presence of a crucial disulphide bond in the active region of the bacteriocin, whose reduction diminished the activity.

Table 1.

Biofilm inhibitory concentration (BIC) of BaCf3 on different biofilm producers

| Bacteria | BIC (µg/mL) |

|---|---|

| Bacillus altitudinus BTMW1 | 0.122 ± 0.047 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa BTRY1 | 0.0607 ± 0.0024 |

| Bacillus sp. SD1 | 0.243 ± 0.094 |

| Bacillus licheniformis SD2 | 0.486 ± 0.019 |

| Staphylococcus warnie DF2 | 0.243 ± 0.094 |

| Micrococcus luteus FF1 | 0.0304 ± 0.0012 |

| Geobacillus stearothermophilus FF2 | 0.486 ± 0.019 |

| Brevibacterium cassie DF1 | 0.0607 ± 0.002 |

| Bacillus niacini DP3 | 0.243 ± 0.094 |

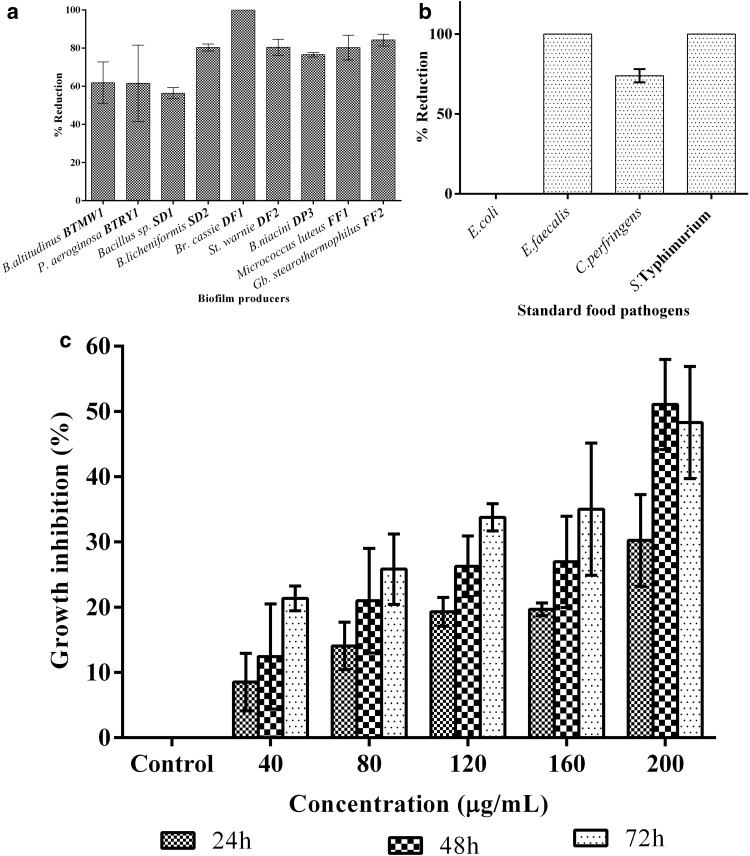

The bacteriocin showed inhibitory activity against all the biofilm producers studied. The Fig. 3a clearly depicts the percentage of biofilm reduction caused by BaCf3 and proved that it could reduce up to 80% biofilm produced by strong biofilm producers from food samples. ANOVA confirmed that the experiment was significant with p < 0.05. Inhibition study of growth and biofilm formation of food pathogens showed significant results on Salmonella Typhimurium (100%), Clostridium perfringens (74%), Enterococcus faecalis (100%); whereas E. coli biofilm was uninhibited (Fig. 3b). Biofilm inhibitory concentration (Table 2) of BaCf3 to inhibit even the strong biofilm producers was < 0.5 µg/mL. Bacteriocins were added directly to cheese to prevent Clostridium and Listeria. Antimicrobial substances produced by B. firmus H2O-1 and B. licheniformis T6-5 strains added to prevent colonization, removed existing biofilms and impacted biofilm structure (Korenblum et al. 2008). Lactobacillus sakei, a bacteriocin-producing lactic acid bacteria is commonly used in the preservation and fermentation of meat products (Champomier-Verges et al. 2001).

Fig. 3.

a Inhibitory action of BaCf3 on food-borne bacteria. b Inhibitory action of BaCf3 on food pathogens. c Growth inhibition of 3-TL3 cell line by different concentrations of BaCf3

Table 2.

Effect of oxidising and reducing agents on the activity of bacteriocins

| Oxidising and reducing agents | % Residual activity in 50 mM | % Residual activity in 100 mM | % Residual activity (Control) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BaCf3 | DMSO | 12.5 | 12.5 | 100 |

| β-Mercaptoethanol | 12.5 | 12.5 | 100 | |

| DTT | 12.5 | No activity | 100 |

The biofilm inhibition of P. aeruginosa and Brevibacterium casei by BaCf3 is an additional advantage since these two organisms are the major contaminants of many food sources. These biofilms are even resistant to most antibiotics (Laxmi and Sarita 2014) and conventional treatments; hence their eradication is a great challenge in food industry.

Cytotoxicity assay using MTT showed that 3T3-L1 cell growth was not much affected by the bacteriocin BaCf3 (Fig. 3c). Even though there was growth inhibition, higher concentration of bacteriocin (200 µg/mL) was required to cause 50% or more inhibition of 3T3-L1 cells. The tests were statistically significant with p < 0.05. While using bacteriocins for human or animal use, it is mandatory to study their effect on normal cells. Rat primary cultured hepatocytes 3T3-L1 with their fibroblast-like morphology represents a valuable tool for screening of bioactive compounds (Wang et al. 2002). From the results, we can notice that the bacteriocin do not show significant growth inhibition on 3T3-L1 cells indicating its applicability in humans/animal use and food preservation. Bacteriocin BL8 which was thermostable and pH tolerant could inhibit biofilms as studied by Laxmi et al. (2016).

The study sheds light to the fact that the bacteriocin can be used to develop antibiofilm surfaces and incorporated in polymeric substances for biofilm prevention in food preservation and biomedical applications. Bacteriocins could also be used for making antibacterial polyurethane films used for food preservation. Thus bacteriocins are safe alternative to commercial preservatives and conventional antibiotics.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge project grants from Centre for Marine Living Resources & Ecology-Ministry of Earth Sciences, Government of India (MOES/10-MLR/2/2007 and MOES/10-MLR-TD/03/2013) given to Dr. Sarita G Bhat, Dept. of Biotechnology, Cochin University of Science and Technology, Kochi, India. The authors also acknowledge Dr. Laxmi. M for providing the biofilm producers.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

E. S. Bindiya, Email: bindiya79@yahoo.co.in

K. J. Tina, Email: tina.kj05@gmail.com

Raghul Subin Sasidharan, Email: raghulzubin@gmail.com.

Sarita G. Bhat, Email: saritagbhat@gmail.com, Email: sgbhat@cusat.ac.in

References

- Alley MC, Scudiero DA, Monks A, Hursey ML, Czerwinski MJ, Fine DL, Abbott BJ, Mayo JG, Shoemaker RH, Boyd MR. Feasibility of drug screening with panels of human tumor cell lines using a microculture tetrazolium assay. Cancer Res. 1988;48:589–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bindiya ES, Tina KJ, Raghul SS, Bhat SG. Characterization of deep sea fish gut bacteria with antagonistic potential, from Centroscyllium fabricii (Deep Sea Shark) Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins. 2015;7:157–163. doi: 10.1007/s12602-015-9190-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaieb K, Kouidhi B, Jrah H, Mahdouani K, Bakhrouf A. Antibacterial activity of Thymoquinone, an active principle of Nigella sativa and its potency to prevent bacterial biofilm formation. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2011;11:29. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-11-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champomier-Vergès MC, Chaillou S, Cornet M, Zagorec M. Lactobacillus sakei: recent developments and future prospects. Res Microbiol. 2001;152:839–848. doi: 10.1016/S0923-2508(01)01267-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopra L, Singh G, Jena KK, Sahoo DK. Sonorensin: a new bacteriocin with potential of an anti-biofilm agent and a food biopreservative. Sci Rep. 2015;5:13412. doi: 10.1038/srep13412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa GA, Rossatto FC, Medeiros AW, Correa APF, Brandelli A, Frazzon APG, Motta ADS. Evaluation antibacterial and antibiofilm activity of the antimicrobial peptide P34 against Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus faecalis. An Acad Bras Ciênc. 2018;90:73–84. doi: 10.1590/0001-3765201820160131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costerton JW, Cheng KJ, Geesey GG, Ladd TI, Nickel JC, Dasgupta M, Marrie TJ. Bacterial biofilms in nature and disease. Ann Rev Microbiol. 1987;4:435–464. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.41.100187.002251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deraz SF, Karlsson EN, Hedström M, Andersson MM, Mattiasson B. Purification and characterisation of acidocin D20079, a bacteriocin produced by Lactobacillus acidophilus DSM 20079. J Biotechnol. 2005;117:343–354. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enan G, El-Essway AA, Uyttendaele M, Debevere J. Antibacterial activity of Lactobacillus plantarum UG1 isolated from dry sausage: characterization, production and bactericidal action of plantaricin UG1. Int J Food Microbiol. 1996;30:189–215. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(96)00947-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh HF, Philip K. Purification and characterization of bacteriocin produced by Weissella confusa A3 of dairy origin. PLoS One. 2015;10:0140434. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyns W, De Moor P. The binding of 17β-hydroxy-5α-androstan-3-one to the steroid binding β-globulin in human plasma, as studied by means of ammonium sulphate precipitation. Steroids. 1971;18:709–730. doi: 10.1016/0039-128X(71)90031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt DF, Henderson RA, Shabanowttz J, Sakaguchi K, Michel H, Sevilir N, Cox AL, Appella E, Engelhard VH. Characterization of peptides bound to the class I MHC molecule HLA-A2. 1 by mass spectrometry. J Immunol. 2007;179:2669. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson DW, Suzuki K, Oakford L, Simecka JW, Hart ME, Romeo T. Biofilm formation and dispersal under the influence of the global regulator CsrA of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:290–301. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.1.290-301.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korenblum E, Sebastián GV, Paiva MM, Coutinho CM, Magalhães FC, Peyton BM, Seldin L. Action of antimicrobial substances produced by different oil reservoir Bacillus strains against biofilm formation. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;79:97–103. doi: 10.1007/s00253-008-1401-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laxmi M, Sarita GB. Diversity characterization of biofilm forming microorganisms in food sampled from local markets in Kochi, Kerala, India. Int J Recent Sci Res. 2014;5:1070–1075. [Google Scholar]

- Laxmi M, Kurian NK, Smitha S, Bhat SG. Melanin and bacteriocin from marine bacteria inhibit biofilms of foodborne pathogens. Ind J Biotechnol. 2016;15:392–399. [Google Scholar]

- Lewus CB, Kaiser A, Montville TJ. Inhibition of food-borne bacterial pathogens by bacteriocins from lactic acid bacteria isolated from meat. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:1683–1688. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.6.1683-1688.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayr-Harting A, Hedges AJ, Berkeley CW. Methods for studying bacteriocins. Methods Microbiol. 1972;7:315–412 18. doi: 10.1016/S0580-9517(08)70618-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Niedermeyer TH, Strohalm M. mMass as a software tool for the annotation of cyclic peptide tandem mass spectra. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44913. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papanyan Z, Markarian S. Detection of oxidation of l-cysteine by dimethyl sulfoxide in aqueous solutions by IR spectroscopy. J Appl Spectrosc. 2013;80:775. doi: 10.1007/s10812-013-9841-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sebei S, Zendo T, Boudabous A, Nakayama J, Sonomoto K. Characterization, N-terminal sequencing and classification of cerein MRX1, a novel bacteriocin purified from a newly isolated bacterium: Bacillus cereus MRX1. J Appl Microbiol. 2007;103:1621–1631. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanks RM, Dashiff A, Alster JS, Kadouri DE. Isolation and identification of a bacteriocin with antibacterial and antibiofilm activity from Citrobacter freundii. Arch Microbiol. 2012;194:575–587. doi: 10.1007/s00203-012-0793-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevchenko A, Tomas H, Havlis J, Olsen JV, Mann M. In-gel digestion for mass spectrometric characterization of proteins and proteomes. Nat Protoc. 2007;1:2856–2860. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spížek J, Novotná J, Řezanka T, Demain AL. Do we need new antibiotics? The search for new targets and new compounds. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;37:1241–1248. doi: 10.1007/s10295-010-0849-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent SS, John SB. Buffers: principles and practice. In: Richard RB, Murray PD, editors. Methods in enzymology. Massachusetts: Elsevier Science & Technology Books; 2009. pp. 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Shindoh H, Inoue T, Horii I. Advantages of in vitro cytotoxicity testing by using primary rat hepatocytes in comparison with established cell lines. J Toxicol Sci. 2002;27:229–237. doi: 10.2131/jts.27.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson K, Walker J, editors. Principles and techniques of practical biochemistry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2015) WHO estimates of the global burden of foodborne diseases: foodborne disease burden epidemiology reference group 2007-2015. World Health Organization No. 9789241565165

- Yamamoto Y, Togawa Y, Shimosaka M, Okazaki M. Purification and characterization of a novel bacteriocin produced by Enterococcus faecalis strain RJ-11. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:5746–5753. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.10.5546-5553.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.