Abstract

Cytoplasmic male sterility (CMS) lines are widely used for hybrid production in Brassica napus. The Shaan2A CMS system is one of the most important in China and has been used for decades; however, the male sterility mechanism underlying Shaan2A CMS remains unknown. Here, we performed transcriptomic and proteomic analysis, combined with additional morphological observation, in the Shaan2A CMS. Sporogenous cells, endothecium, middle layer, and tapetum could not be clearly distinguished in Shaan2A anthers. Furthermore, Shaan2A anther chloroplasts contained fewer starch grains than those in Shaan2B (a near-isogenic line of Shaan2A), and the lamella structure of chloroplasts in Shaan2A anther wall cells was obviously aberrant. Transcriptomic analysis revealed differentially expressed genes (DEGs) mainly related to carbon metabolism, lipid and flavonoid metabolism, and the mitochondrial electron transport/ATP synthesis pathway. Proteomic results showed that differentially expressed proteins were mainly associated with carbohydrate metabolism, energy metabolism, and genetic information processing pathways. Importantly, nine gene ontology categories associated with anther and pollen development were enriched among down-regulated DEGs at the young bud (YB) stage, including microsporogenesis, sporopollenin biosynthetic process, and tapetal layer development. Additionally, 464 down-regulated transcription factor (TF) genes were identified at the YB stage, including some related to early anther differentiation such as SPOROCYTELESS (SPL, also named NOZZLE, NZZ), DYSFUNCTIONAL TAPETUM 1 (DYT1), MYB80 (formerly named MYB103), and ABORTED MICROSPORES (AMS). These results suggested that the sterility gene in the Shaan2A mitochondrion might suppress expression of these TF genes in the nucleus, affecting early anther development. Finally, we constructed an interaction network of candidate proteins based on integrative analysis. The present study provides new insights into the molecular mechanism of Shaan2A CMS in B. napus.

Keywords: cytoplasmic male sterility, transcriptome, proteome, transcription factor, anther differentiation, mitochondria, chloroplasts

Introduction

Rapeseed (Brassica napus) is an important oil crop producing both edible oil and industrial materials such as lubricants and biodiesel. Heterosis is widely observed in B. napus, with excellent hybrids having yields over 30% higher than their parents (Radoev et al., 2008). Hybrid breeding largely relies on male-sterile lines, mainly involving chemically induced male sterility (CIMS), genic male sterility (GMS), and cytoplasmic male sterility (CMS) (Chen and Liu, 2014). In higher plants, CMS is a maternally inherited trait, which is largely resulting from rearrangements of mitochondrial DNA, which results in an inability to generate pollen or in abnormal pollen (Schnable and Wise, 1998; Horn et al., 2014). The first CMS line was found in onion (Jones and Clarke, 1943). To date, CMS has been observed in more than 150 plant species (Laser and Larsten, 1972; Schnable and Wise, 1998). Four major CMS systems have been used in rapeseed production: nap CMS (Shiga and Baba, 1971), pol CMS (Fu, 1981), Ogu CMS (Ogura, 1968), and Shaan2A CMS (Li, 1980). pol CMS and Shaan2A CMS are the most commonly used CMS systems in B. napus in terms of number of three-line hybrids and the area planted with these hybrids (Fu, 1995).

In recent years, transcriptomic and proteomic analyses have been used in CMS studies. The transcriptome of CMS onion revealed three nuclear-related genes, AGAMOUS (AG), ABORTED MICROSPORES (AMS), and SOMATIC EMBRYOGENESIS RECEPTOR-LIKE KINASE 1 (SERK1) (Yuan et al., 2018). Transcriptomic analysis in Gossypium hirsutum indicated decreased ability to eliminate reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the CMS line, with ROS released from mitochondria acting as signal molecules in the nucleus, triggering formation of abnormal tapetum (Suzuki et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2018). In Ogu CMS, key genes participating in the secretion and translocation of sporopollenin precursors were significantly down-regulated in the cabbage R2P2CMS line (Xing et al., 2018). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) involved in protein synthesis and metabolic pathways have been identified between sterile and maintainer lines in both pol CMS and SaNa-1A CMS in B. napus (An et al., 2014; Du et al., 2016).

In flowering plants, anthers are important organs that generate pollen grains for propagation. In Arabidopsis, anther development has been systematically divided into 14 stages (Sander et al., 1999). First, the stamen primordium arises from the floral apex, then the archesporial cells from the four corners of the L2 cell layer undergo a series of differentiation and division events to promote formation of the four microsporangia of the butterfly shaped anther (Feng and Dickinson, 2007). These processes are controlled by a number of genes that function downstream of floral identity genes, most of them unknown. In Arabidopsis, AG has dual roles in limiting stem cell proliferation and determining floral organ identities (Lohmann et al., 2001). SPL, encoding a MADs transcription factor (TF), is a direct downstream gene of AG and the candidate gene for specifying the identity, position, and number of archesporial cells in the anther L2 layer; microsporogenous cells are not generated in the spl mutant (Schiefthaler et al., 1999; Yang et al., 1999). Another gene, HYPONASTIC LEAVES1 (HYL1), modulates the stamen architecture of the four microsporangia by coordinating expression of REVOLUTA (REV) and FILAMENTOUS FLOWER (FIL) through miR165/166 in Arabidopsis (Lian et al., 2013). Interestingly, FIL directly interacts with SPL (Sieber, 2004). Recently, GROWTH-REGULATING FACTOR (GRF) and GRF-INTERACTING FACTOR (GIF) were identified as novel positive regulators in specifying archesporial cells in Arabidopsis, and grf1/2 and gif1/2 mutants show a similar phenotype to the spl mutant (Lee et al., 2018). BARELY ANY MERISTEM (BAM1 and BAM2) encode CLAVATA1-related and leucine-rich repeat (LRR) receptor-like kinases, and anthers in the double mutant bam1 bam2 exhibit abnormalities at a very early stage, lacking the tapetum, middle layers, and endothecium (Hord, 2006). EXCESS MICROSPOROCYTES 1 (EMS1, also known as EXTRA SPOROGENOUS CELLS, EXS) also encodes a putative LRR receptor kinase, regulating tapetum identity and number of reproductive cells in Arabidopsis (Canales et al., 2002; Zhao et al., 2002). Interestingly, SPL is expressed in most early anther development mutants, for example, bam1/2 double mutants and ems1 (Canales et al., 2002; Zhao et al., 2002; Hord, 2006), indicating that SPL might be the first “reproductive gene” to be activated in anther development.

Shaan2A CMS was identified by Professor Dianrong Li in 1976, and the representative hybrid rapeseed cultivar ‘Qinyou 2’ was generated using the Shaan2A CMS line and its restorer line KC01. This was the first three-line hybrid cultivar in China, and was widely cultivated from 1985 to 2008 (Li and Tian, 2015). Although the Shaan2A CMS system has been widely used in the production of hybrids for decades, its male sterility mechanism remains unclear. In the present study, we performed transcriptomic and proteomic analyses, combined with additional morphological observation, to reveal the mechanism of Shaan2A CMS. We aimed to identify differences between the sterile line Shaan2A and its maintainer line Shaan2B at the transcriptional and protein level, and elucidate the regulative and metabolic pathways involved in the male sterility. The results will provide new insights into the molecular mechanism of Shaan2A CMS in B. napus.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials

Male sterile plants were found among hybrid offspring by Professor Dianrong Li in 1976. The male sterile lines were conserved by self-fertilization with limited pollen, hybridization of sister plants, and test crossing of different rapeseed cultivars. The male sterile Shaan2A line and its maintainer line Shaan2B were then rapidly bred by individual pollination of a single plant, biparental crossing, and mutual selection of parents according to the female parent’s phenotype as well as sterility of the female and agronomic characteristics of the parents. In the present study, Shaan2A and Shaan2B were cultivated in the test field of Huazhong University of Science and Technology (Wuhan, Hubei, China) under the same conditions. Plant samples were quickly removed from buds of different length on ice and frozen in liquid nitrogen, then kept at −80°C for extraction of total RNA and protein.

Observation of Paraffin Sections and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

Anthers of different length were vacuum-infiltrated and fixed with 50%FAA (v/v) and 2.5% (w/v) glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). For paraffin section analysis, fixed materials were dehydrated through a graded series of ethanol (70, 85, 90, 95, 2 × 100%) and then cleared twice with xylene for 2 h. The material was infiltrated with Paraffin wax and subsequently embedded in paraffin wax. Finally, sections of approximately 10 μm were obtained using a KD-1508A microtome (China) and observed under a LEICA DMLB microscope (Germany) with a CCD camera (DFC420 FX). Procedures for TEM observation followed a previous study (Yi et al., 2010) with minor modification (Ning et al., 2018).

Proteomic Analysis

Different-sized anthers were collected from flower buds and mixed together. Preparation of total protein, two-dimensional electrophoresis (2-DE), analysis of differentially expressed proteins (DEPs), and protein identification by MALDI-TOF-MS-MS were conducted as described previously (Gan et al., 2013; Ning et al., 2018).

Transcriptomic Analysis

B. napus anthers from buds <0.5, 0.5–1, 1–1.5, and 1.5–2.0 mm are at the pollen mother cell stage, meiosis stage, tetrad stage, and stage of microspore release from the tetrad, respectively (Zhou et al., 2012). Young buds (YB) shorter than 1 mm represented the stage before meiosis, and small anthers (SA) in 1–2 mm buds represented the tetrad stage to the microspore release stage. Total RNA extraction, assembly, and mapping of clean reads, and annotation of the transcriptome were conducted according to a previous report (Ning et al., 2018). For Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis1, KOBAS software was used to test the statistical enrichment of DEGs in KEGG pathways.

qRT-PCR

Total RNA was reverse-transcribed using ReverTra Ace® qPCR-RT Master Mix with gDNA Remover (TOYOBO) according to the protocol of manufacturer, with actin as an internal reference gene (An et al., 2014). qRT-PCR experiments were conducted and calculations performed as described previously (Miao et al., 2016). All primer sequences are given in Supplementary Table S1.

Interaction Analysis

Interaction analysis of DEGs and DEPs was based on the STRING database2, including known and predicted protein–protein interactions. Blastx (v2.2.28) was used to align target gene sequences to reference protein sequences, and a network was constructed according to known interactions in Arabidopsis thaliana.

Results

Morphological and Cytological Comparison Between Shaan2A and Shaan2B

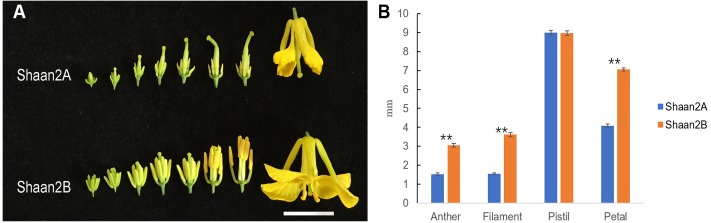

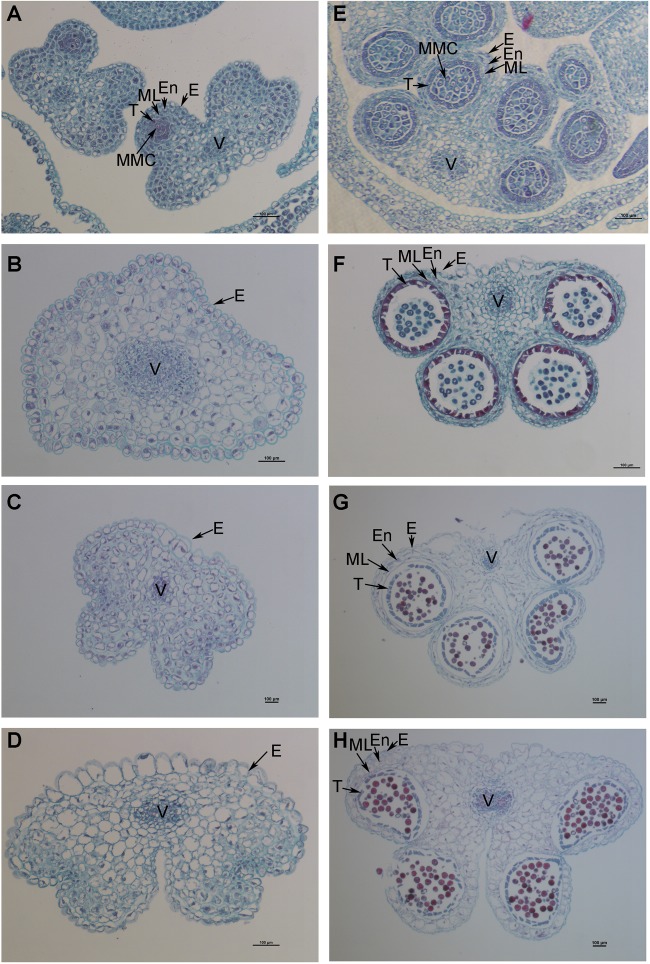

The petals of Shaan2B flowers were significantly wider than those of Shaan2A flowers, and the anthers and filaments in Shaan2B were obviously longer than those in Shaan2A (Figure 1A,B). The anthers in Shaan2A appeared to stop developing at an early stage and hardly split, releasing pollen eventually, while the pistil in Shaan2B was normal. Cytological differences between the anthers of Shaan2A and Shaan2B are shown in Figure 2. The anthers in 1 mm buds of Shaan2B were developed normally, and it was easy to distinguish the sporogenous cells and the middle layer, endothecium, and tapetum (Figure 2E). However, most of the anther locules in 1 mm buds of Shaan2A were differentiated abnormally, and the anther wall and sporogenous cells could not be clearly distinguished (Figure 2A). In 2–4 mm buds, the anthers of Shaan2B were well developed, while the anthers in Shaan2A were obviously aberrant (Figure 2).

FIGURE 1.

Phenotypic characterization of fertile and sterile buds. (A) Shaan2A and Shaan2B buds. Bar: 1 cm. (B) Length of anther, filament, and pistil, and width of petal in opened flowers (Student’s t-test,∗∗P < 0.01).

FIGURE 2.

Dynamic observation of paraffin sections of Shaan2A and Shaan2B anthers. (A) Anthers in 1 mm buds of Shaan2A. (B) Anthers in 2 mm buds of Shaan2A. (C) Anthers in 3 mm buds of Shaan2A. (D) Anthers in 4 mm buds of Shaan2A. (E) Anthers in 1 mm buds of Shaan2B. (F) Anthers in 2 mm buds of Shaan2B. (G) Anthers in 3 mm buds of Shaan2B. (H) Anthers in 4 mm buds of Shaan2B. E, epidermis; En, endothecium; ML, middle layer; T, tapetum; MMC, microspore mother cells; V, vascular region. Bar: 100 μm.

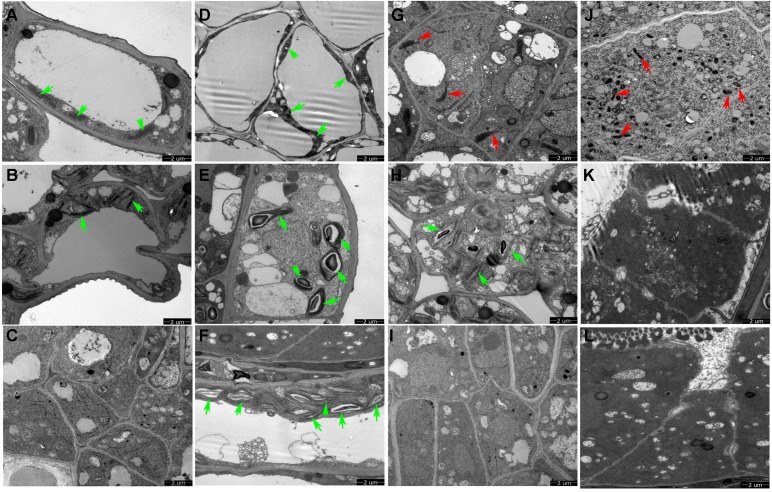

We conducted TEM observation to further understand ultrastructural differences in the anther wall between Shaan 2A and Shaan2B. As shown in Figure 3A, epidermis cells in 1 mm buds of Shaan2A had few starch grains in chloroplasts and a large vacuole. Except for the large vacuole, Shaan2B epidermis cells had starch grains in most of the chloroplasts (Figure 3D). Tapetum cells in 1 mm buds of Shaan2A had a few mitochondria (2.8 ± 0.98) (Figure 3G), while those in Shaan2B were enriched with mitochondria (19 ± 1.55) (Figure 3J). The lamella structure of chloroplasts in both epidermis and tapetum cells were obviously abnormal in 2 mm buds of Shaan2A (Figure 3B,H). However, lamella structure in Shaan2B was normal (Figure 3E), and the structure of tapetum cells in Shaan2B (Figure 3K) were distant not alike with those in Shaan2A (Figure 3H). Moreover, epidermis and tapetum cells in 3 mm buds of Shaan2A had the same structure (Figure 3C,I), while those of Shaan2B exhibited different differentiation (Figure 3F,L). The different cell layers in anther walls during early anther differentiation are roughly shown in Supplementary Figure S1. These phenomena indicated that the differentiation of anther wall cells in Shaan2A was disordered.

FIGURE 3.

TEM observation of epidermis and tapetum cells of Shaan2A and Shaan2B anther walls. (A) Epidermis cells in 1 mm buds of Shaan2A. (B) Epidermis cells in 2 mm buds of Shaan2A. (C) Epidermis cells in 3 mm buds of Shaan2A. (D) Epidermis cells in 1 mm buds of Shaan2B. (E) Epidermis cells in 2 mm buds of Shaan2B. (F) Epidermis cells in 3 mm buds of Shaan2B. (G) Tapetum cells in 1 mm buds of Shaan2A. (H) Tapetum cells in 2 mm buds of Shaan2A. (I) Tapetum cells in 3 mm buds of Shaan2A. (J) Tapetum cells in 1 mm buds of Shaan2B. (K) Tapetum cells in 2 mm buds of Shaan2B. (L) Tapetum cells in 3 mm buds of Shaan2B. Green arrows indicate chloroplasts and red arrows represent mitochondria. Bar: 2 μm.

Comparative Transcriptomic Analysis Between Shaan2A and Shaan2B

We used comparative transcriptomics to identify genes associated with male sterility in Shaan2A CMS. RNA-seq of three biological replicates at the YB (<1 mm buds, before meiosis) and SA (1–2 mm buds, representing tetrad to microspore release) stages generated 637,533,762 raw reads. The raw reads were deposited in the SRA (NCBI Sequence Read Archive) database under accession number PRJNA502996. These raw data were filtered to obtain clean reads, of which over 90% perfectly matched to the reference genome (Chalhoub et al., 2014). More detailed information for RNA-seq data is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of RNA-seq data.

| Sample | Replicate | Raw reads | Clean reads | GC content (mol%) | Total mapped | Multiply mapped | Uniquely mapped |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2A_YB | 2A_YB1 | 44,035,120 | 43605746 | 46.96 | 39,475,845 (90.53%) | 1,639,764 (3.76%) | 37,836,081 (86.77%) |

| 2A_YB2 | 45,983,586 | 45630640 | 46.85 | 41,183,271 (90.25%) | 1,686,124 (3.70%) | 39,497,147 (86.56%) | |

| 2A_YB3 | 45,953,444 | 45231052 | 47.04 | 40,916,267 (90.46%) | 1,715,471 (3.79%) | 39,200,796 (86.67%) | |

| 2A_SA | 2A_SA1 | 59,213,734 | 58019808 | 46.09 | 52,317,347 (90.17%) | 2,184,243 (3.76%) | 50,133,104 (86.41%) |

| 2A_SA2 | 59,374,138 | 58794086 | 46.2 | 53,061,323 (90.25%) | 2,147,433 (3.65%) | 50,913,890 (86.6%) | |

| 2A_SA3 | 62,914,554 | 62064672 | 46.42 | 56,103,044 (90.39%) | 2,325,942 (3.75%) | 53,777,102 (86.65%) | |

| 2B_YB | 2B_YB1 | 50,061,626 | 49538462 | 46.88 | 44,776,518 (90.39%) | 1,864,618 (3.76%) | 42,911,900 (86.62%) |

| 2B_YB2 | 62,070,224 | 61306156 | 46.82 | 55,684,014 (90.83%) | 2,297,159 (3.75%) | 53,386,855 (87.08%) | |

| 2B_YB3 | 46,417,324 | 45834614 | 46.95 | 41,562,082 (90.68%) | 1,664,307 (3.63%) | 39,897,775 (87.05%) | |

| 2B_SA | 2B_SA1 | 55,769,766 | 55185458 | 45.98 | 49,900,475 (90.42%) | 2,448,037 (4.44%) | 47,452,438 (85.99%) |

| 2B_SA2 | 52,729,352 | 51938752 | 46.21 | 47,032,360 (90.55%) | 2,219,473 (4.27%) | 44,812,887 (86.28%) | |

| 2B_SA3 | 53,010,894 | 52211658 | 46.12 | 47,256,054 (90.51%) | 2,307,822 (4.42%) | 44,948,232 (86.09%) |

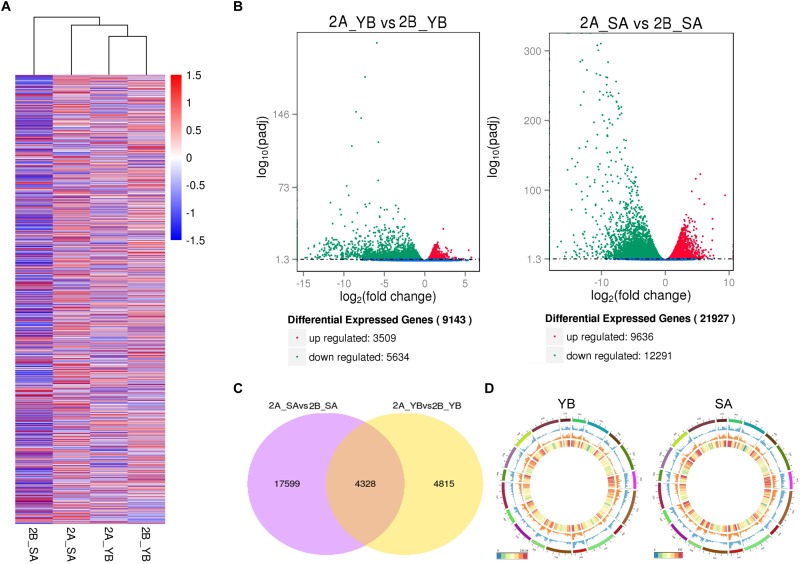

We performed hierarchical cluster analysis of all DEGs to examine global gene expression patterns in different samples (Figure 4A). Shaan2A_YB and Shaan2B_YB showed similar global expression patterns. When compared with Shaan2B, a total of 3,509 and 9,636 up-regulated DEGs and 5,634 and 12,291 down-regulated DEGs (P < 0.05) were identified at the YB and SA stages in Shaan2A, respectively (Figure 4B). The number of DEGs shared at the two stages was 4,328, only 1/5 of the total DEGs at the SA stage (Figure 4C). The number of DEGs, and the densities of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and insertions and deletions (indels) in different chromosomal regions at the YB and SA stages, respectively, are shown in Figure 4D. High-density areas of both SNPs and indels were focused on chromosomes A01, A02, A03, and A05, and DEGs were more concentrated in genome A than genome C.

FIGURE 4.

Statistical analysis of gene expression detected by transcriptomic analysis. (A) Heatmap analysis of all DEGs at the different stages. (B) Volcano plot of up- and down-regulated genes at the YB and SA stages. (C) Venn diagram showing common DEGs at the two stages. (D) Circle plot of the distribution of SNPs and indels, and the density of DEGs in different chromosomal regions. The outermost layer represents all B. napus chromosomes (A01–A10 and C01–C09). The blue layer represents the distribution of SNPs, the middle orange layer shows the distribution of indels, and the innermost layer indicates the density of DEGs.

KEGG analysis (P < 0.05) of DEGs between Shaan2A and Shaan2B at the two stages revealed that pathways associated with protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum, carbon metabolism, and fatty acid degradation were enriched at the YB stage (Supplementary Table S2), as some genes in these pathways, such as HEAT SHOCK PROTEIN (Hsp70), SHEPHERD (SHD), and LONG CHAIN ACYL-COA SYNTHETASE 9 (LACS9) were significantly differentially expressed. In Arabidopsis, Hsp70 is a molecular chaperone that plays numerous important roles in protein folding (Wisén and Gestwicki, 2008). At the SA stage, genes associated with starch and sucrose metabolism, porphyrin and chlorophyll metabolism, and carbon metabolism pathways were annotated (Supplementary Table S2). Among these genes, FERROCHELATASE (FC) and CHLOROPHYLLASE (CLH) were identified. FC is the last enzyme for heme biosynthesis in the tetrapyrrole pathway and is essential for stress tolerance in Arabidopsis (Chow et al., 1998; Fan et al., 2018).

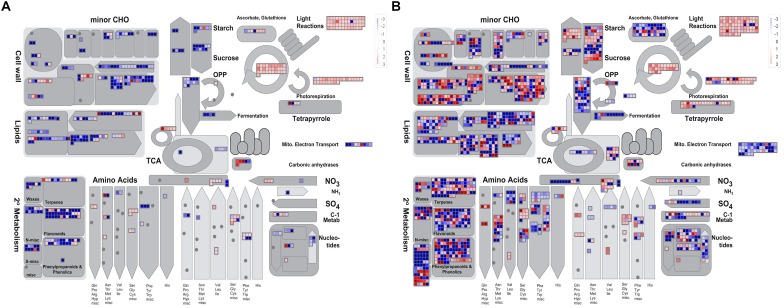

To obtain an overview of the pathways in which the DEGs participated, we further analyzed the DEGs (| log2 ratio| > 1) at the YB and SA stages using MapMan software. The metabolism pathway visualization is shown in Figure 5, and detailed information is listed in Supplementary Table S3. Although the DEGs were dispersed in different primary and secondary metabolism pathways, most involved in lipid and flavonoid metabolism and mitochondrial electron transport/ATP synthesis pathways were down-regulated at both the YB (Figure 5A) and SA (Figure 5B) stages; for example, BnaA02g21480D, which encodes a member of the SMO1 family of sterol 4-alpha-methyl oxidases in the lipid metabolism pathway, and BnaA02g33800D, encoding flavonol synthase 3 (FLS3) in the flavonoid metabolism pathway. Interestingly, a large number of DEGs were up-regulated in light reactions, photorespiration, and the Calvin cycle (Figure 5A,B). These included BnaA03g22080D, which encodes a PsbP domain-OEC23 like protein localized in thylakoids (peripheral-lumenal side) in the light reaction pathway, BnaA01g00170D, which encodes a protein with mitochondrial serine hydroxymethyl transferase activity and functions in the photorespiration pathway, and BnaC04g05700D, which encodes a Rubisco activase and functions in the Calvin cycle.

FIGURE 5.

Overview of the metabolic pathways the DEGs were involved in at the YB and SA stages. (A) Overview of YB stage. (B) Overview of SA stage.

Furthermore, 11 DEGs related to anther development were selected for qRT-PCR validation (Supplementary Figure S2), for example, BnaA01g09760D (AG), BnaA10g23720D (EMS1), and BnaA01g16350 (SPL). Most of the expression patterns of these DEGs at the two stages were basically consistent with the RNA-seq data, indicating that the RNA-seq data were reliable.

Comparative Proteomic Analysis Between Shaan2A and Shaan2B

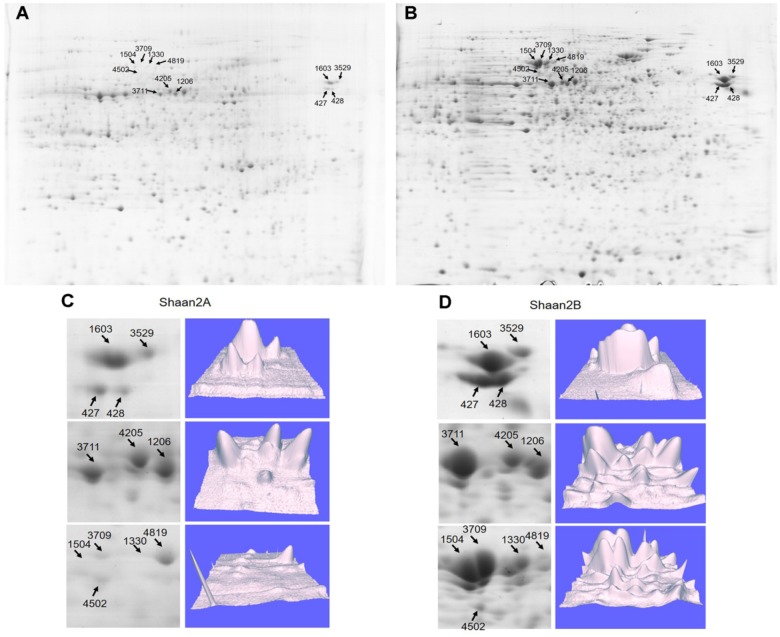

To detect DEPs between Shaan2A and Shaan2B, we conducted 2-DE with three biological triplicates using total protein from anthers of Shaan2A and Shaan2B. Approximately 1,000 protein spots were detected (Figure 6A,B). DEPs exceeding the least significant difference (p < 0.05) and showing more than twofold change in abundance were chosen for MALDITOF-MS-MS analysis.

FIGURE 6.

Representative images of DEPs between Shaan2A and Shaan2B. (A) Shaan2A 2-DE images. (B) Shaan2B 2-DE images. (C) Enlarged area of 2-DE gel and 3D images of Shaan2A. (D) Enlarged area of 2-DE gel and 3D images of Shaan2B.

Compared with Shaan2B, 13 and 53 DEPs showed increased and decreased expression, respectively, in Shaan2A (Table 2). These DEPs were grouped into 11 categories, including “genetic information processing” (28.8%), “carbohydrate metabolism” (18.2%), “energy metabolism” (15.2%), and “amino acid metabolism” (9.1%) (Table 2). The enlarged 3D area of the 2-DE gel of some representative DEPs is shown in Figure 6C,D. For example, hydroxycinnamoyl-CoA: shikimate hydroxycinnamoyl transferase (spot 1603; HCT, AT5G48930) is related to the accumulation of flavonoids and in turn represses auxin transport to inhibit plant growth (Li et al., 2010). Methionine adenosyltransferase 4 (spot 3529; MAT4, AT3G17390) plays an important role in S-adenosyl-Met (SAM) production and plant development (Meng et al., 2018). β-Ketoacyl-[acyl carrier protein] synthase I (spot 1504; KASI, AT5G46290) is important for fatty acid synthesis and plays a key role in embryo development and chloroplast division (Wu and Xue, 2010). More details are shown in Table 2, and all of these proteins were down-regulated in Shaan2A.

Table 2.

Identification and relative expression level of DEPs.

| Spot no. | Identified protein | Arabidopsis homolog | Mr | Score | Relative expression level |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shaan2A | Shaan2B | |||||

| Amino acid metabolism | ||||||

| 115 | Glutathione S-transferase | AT2G30860 | 22,630 | 130 | 4,671.87 | 500.30 |

| 2535 | S-Adenosylmethionine synthase 2 | AT4G01850 | 43,627 | 539 | 189.00 | 3,546.70 |

| 3529 | S-Adenosylmethionine synthase 2 | AT3G17390 | 43,309 | 300 | 206.40 | 600.83 |

| 8302 | Spermidine synthase 1; SPDSY 1 | AT1G23820 | 36,986 | 290 | 71.60 | 272.43 |

| 8311 | Spermidine synthase 1; SPDSY 1 | AT1G23820 | 36,986 | 572 | 471.43 | 969.47 |

| 1106 | Glutathione S-transferase | AT2G30860 | 59,422 | 241 | 6,979.03 | 1,108.27 |

| Biosynthesis of other secondary metabolites | ||||||

| 1603 | PREDICTED: hydroxycinnamoyl-coenzyme A shikimate/quinate hydroxycinnamoyltransferase-like | AT5G48930 | 47,658 | 47 | 737.73 | 3,454.70 |

| Carbohydrate metabolism | ||||||

| 329 | Similar to uridine diphosphate glucose epimerase; F8M12.10 | AT4G10960 | 38,804 | 66 | 305.97 | 2,293.53 |

| 423 | Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase, class I | AT3G52930 | 38,858 | 405 | 0.00 | 277.00 |

| 427 | Unnamed protein product | AT1G13440 | 32,088 | 430 | 618.40 | 1,761.33 |

| 428 | Acetyl-CoA C-acetyltransferase | AT5G48230 | 51,531 | 285 | 557.00 | 2,071.93 |

| 2325 | Putative aldose 1-epimerase | AT3G17940 | 35,355 | 60 | 148.57 | 1,120.93 |

| 2426 | Glutamate-ammonia ligase (EC 6.3.1.2), cytosolic (clone lambdaAtgskb6) – Arabidopsis thaliana | AT3G17820 | 40,932 | 140 | 2,440.57 | 5,153.13 |

| 2502 | Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase large subunit | ATCG00490 | 53,282 | 555 | 22,765.10 | 3,667.27 |

| 3223 | Stromal ascorbate peroxidase | AT4G08390 | 38,737 | 272 | 108.83 | 504.83 |

| 3611 | Inositol-3-phosphate synthase | AT2G22240 | 56,487 | 129 | 64.03 | 488.60 |

| 3711 | ATA27 | AT1G75940 | 62,096 | 77 | 300.67 | 3,023.13 |

| 4101 | Nuclear-encoded chloroplast stromal cyclophilin CYP20-3 (also known as ROC4) | AT3G62030 | 26,725 | 363 | 2,615.93 | 621.03 |

| 6406 | Glutamine synthetase, chloroplastic | AT5G35630 | 47,714 | 626 | 274.30 | 753.23 |

| Cellular processes | ||||||

| 5423 | Actin-3 | AT3G53750 | 42,022 | 538 | 462.07 | 2,382.53 |

| Energy metabolism | ||||||

| 215 | Predicted NADH dehydrogenase 24 kD subunit | AT4G02580 | 27,564 | 82 | 320.23 | 2,120.83 |

| 1206 | S-Formylglutathione hydrolase | AT2G41530 | 31,921 | 71 | 455.93 | 968.10 |

| 3104 | Quinone reductase family protein | AT4G27270 | 21,778 | 175 | 46.90 | 247.10 |

| 4117 | Chlorophyll a-b binding protein 6A, chloroplastic | AT3G54890 | 26,786 | 276 | 3,425.50 | 544.90 |

| 4205 | O-Acetylserine (thiol)-lyase | AT4G14880 | 33,995 | 110 | 137.63 | 429.27 |

| 6113 | Oxygen-evolving enhancer protein 2, chloroplastic | AT1G06680 | 26,712 | 268 | 4,478.83 | 1,069.63 |

| 6236 | V-type proton-ATPase | AT4G11150 | 26,282 | 300 | 2,855.87 | 9.40 |

| 6523 | ATP synthase beta subunit | ATCG00480 | 35,998 | 210 | 1,494.23 | 275.73 |

| 6620 | Nucleotide-binding subunit of vacuolar ATPase | AT1G76030 | 54,819 | 335 | 1,170.23 | 272.30 |

| 7202 | Photosystem II subunit O-2 | AT3G50820 | 35,323 | 764 | 9,246.37 | 2,165.53 |

| Genetic information processing | ||||||

| 6310 | 60S acidic ribosomal protein PO | AT3G09200 | 33,775 | 129 | 395.73 | 2,349.70 |

| 219 | Multicatalytic endopeptidase | AT5G40580 | 23,960 | 162 | 197.47 | 669.53 |

| 1733 | F23N19.10 | AT1G62740 | 67,625 | 93 | 90.47 | 420.27 |

| 1818 | Unnamed protein product | AT1G56070 | 94,734 | 314 | 129.30 | 999.50 |

| 2112 | AT3g62030 | AT3G62030 | 28,532 | 102 | 3,685.03 | 399.87 |

| 3034 | SERINE CARBOXYPEPTIDASE II-like protein | AT4G30810 | 47,658 | 158 | 162.33 | 417.30 |

| 3421 | Carboxypeptidase Y-like protein | AT3G10410 | 60,386 | 139 | 1,789.60 | 4,428.77 |

| 3627 | ATP-dependent Clp protease ATP-binding subunit ClpC | AT5G50920 | 103,616 | 618 | 137.60 | 712.53 |

| 4303 | Thiol protease isoform B, partial | AT4G39090 | 35,687 | 54 | 203.93 | 839.57 |

| 4502 | Translational initiation factor 4A-1 | AT3G13920 | 46,960 | 93 | 56.43 | 226.30 |

| 4530 | Chloroplast elongation factor tub | AT4G20360 | 51,868 | 763 | 288.33 | 836.20 |

| 4819 | Chaperone protein ClpC, chloroplastic | AT5G50920 | 102,818 | 307 | 223.40 | 466.57 |

| 5601 | Hypothetical protein ARALYDRAFT_478789 | AT3G13860 | 60,881 | 289 | 240.83 | 563.97 |

| 6206 | 20S proteasome subunit PAF1 | AT5G42790 | 30,543 | 618 | 131.47 | 363.77 |

| 6208 | 20S proteasome subunit PAF1 | AT5G42790 | 30,543 | 303 | 129.37 | 317.57 |

| 7125 | Immunophilin | AT5G48580 | 17,790 | 118 | 312.90 | 631.67 |

| 8001 | Hypothetical protein ARALYDRAFT_897824 | AT3G15360 | 21,277 | 185 | 756.80 | 1,944.37 |

| 8602 | Protein disulfide-isomerase A1 | AT1G21750 | 55,852 | 165 | 695.37 | 2,317.87 |

| 8604 | Protein disulfide-isomerase A1 | AT1G21750 | 55,852 | 93 | 201.87 | 419.27 |

| Glycan biosynthesis and metabolism | ||||||

| 1706 | Glycosyl hydrolase family 38 protein | AT5G13980 | 11,6351 | 103 | 327.43 | 53.80 |

| 4304 | Reversibly glycosylated polypeptide 1 | AT3G02230 | 41,116 | 371 | 1,145.77 | 2,755.63 |

| 7322 | Alpha-1,4-glucan-protein synthase family protein | AT5G16510 | 39,017 | 293 | 570.67 | 1,520.07 |

| Lipid metabolism | ||||||

| 1306 | Enoyl-[acyl-carrier protein] reductase | AT2G05990 | 40,944 | 438 | 387.17 | 1,824.67 |

| 1504 | 3-Ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase I | AT5G46290 | 50,890 | 220 | 127.87 | 1,155.43 |

| Nucleotide metabolism | ||||||

| 7412 | Adenosine kinase 2 | AT5G03300 | 38,221 | 160 | 37.03 | 209.77 |

| Signal transduction | ||||||

| 3709 | Auxin responsive-like protein | AT5G13370 | 65,180 | 85 | 212.30 | 1,286.10 |

| Unclassified | ||||||

| 1205 | Cysteine proteinase inhibitor | AT3G12490 | 22,988 | 162 | 372.03 | 952.07 |

| 1330 | Annexin E1 | AT5G65020 | 36,109 | 357 | 95.03 | 824.60 |

| 1416 | Chalcone synthase 3 protein | AT1G02050 | 43,493 | 239 | 512.73 | 1,551.23 |

| 2108 | Superoxide dismutase | AT4G25100 | 23,791 | 323 | 9,351.10 | 1,307.23 |

| 3720 | Os09g0511700 | AT1G02850 | 30,364 | 46 | 156.40 | 1,057.57 |

| 4424 | Chalcone synthase 2 protein | AT4G00040 | 43,246 | 444 | 83.77 | 285.20 |

| 6317 | Uncharacterized protein | AT5G08540 | 38,745 | 118 | 707.57 | 2,596.87 |

| 8225 | Thaumatin-like protein | AT1G75050 | 26,267 | 116 | 406.47 | 1,725.40 |

| 3025 | Acyltransferase homolog | AT5G23940 | 50,231 | 54 | 0.00 | 100.93 |

| 8120 | Conserved hypothetical protein | AT5G48480 | 16,993 | 49 | 832.07 | 1,887.43 |

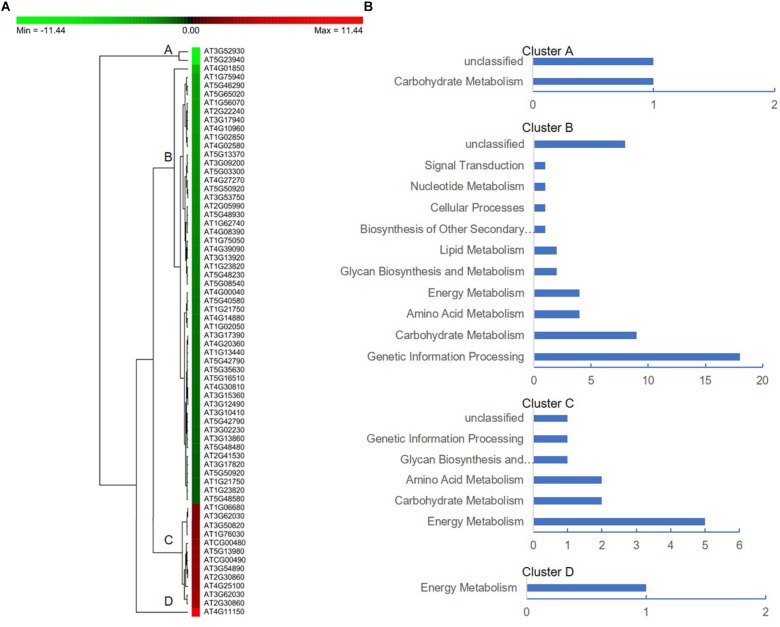

To further facilitate the biological interpretation of the identified DEPs, we conducted hierarchical clustering analysis of the DEPs showing quantitative changes in expression. We identified four clusters of DEPs (Figure 7A) with dramatic changes in expression patterns between fertile and sterile anthers. Cluster A contained two proteins, one belonging to the “carbohydrate metabolism” group and the other unknown (Figure 7B), and both were dramatically down-regulated in Shaan2A compared with Shaan2B. Cluster B, the largest cluster, included 51 proteins down-regulated in Shaan2A, with the “genetic information processing” and “carbohydrate metabolism” categories dominating (Figure 7B); for example, acetyl-CoA C-acetyltransferase protein (spot 428; AT5G48230) and adenosine kinase 2 (spot 7412; AT5G03300). Cluster C proteins showed increased expression in Shaan2A compared with Shaan2B, and included 12 proteins with “energy metabolism” as the dominant classification (Figure 7B); for instance, ATP synthase beta subunit (spot 6523; ATCG00480) and ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase large subunit (spot 2502; ATCG00490). Cluster D contained only one protein with high expression in Shaan2A and low expression in Shaan2B (Figure 7B). This was a V-type proton-ATPase protein related to “energy metabolism.”

FIGURE 7.

Protein expression profiles of the DEPs between Shaan2A and Shaan2B. (A) Hierarchical clustering of proteins showing quantitative changes in expression. (B) Protein functional classification of four clusters.

Correlation Analysis Between DEGs and DEPs

B. napus is an allotetraploid plant, and its genome contains many repeats and homologous sequences (Chalhoub et al., 2014). The 66 DEPs identified in the proteomic analysis corresponded to 344 genes in B. napus. We conducted correlation analysis between DEGs and DEPs at both the YB and SA stage. DEPs and DEGs were divided into four groups according to their expression in Shaan2A compared to Shaan2B (Supplementary Table S4). In Group I, 43 and 115 DEGs showed the same trend in expression as their corresponding DEPs at the YB and SA stage, respectively. For example, actin 3 (AT3G53750) and chalcone and stilbene synthase family protein (AT4G00040), which are associated with protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum, and SAM. In Group II, 21 and 24 DEGs showed the opposite trend in expression from their corresponding DEPs at the YB and SA stage, respectively, such as MAT4 (AT3G17390) and GLN1.3 (AT3G17820), associated with amino acid and carbohydrate metabolism, respectively. In Group III, the corresponding genes of 280 and 205 DEPs at the YB and SA stage, respectively, were not differentially expressed. In Group IV, the genes corresponding to 33 DEPs at the YB stage and 10 DEPs at the SA stage did not show differential expression in the transcriptomic analysis. These results showed that both positive and negative correlations exist between the mRNA and protein expression profiles at different stages, indicating that there might be a complex post-transcriptional regulatory network in Shaan2A male sterility.

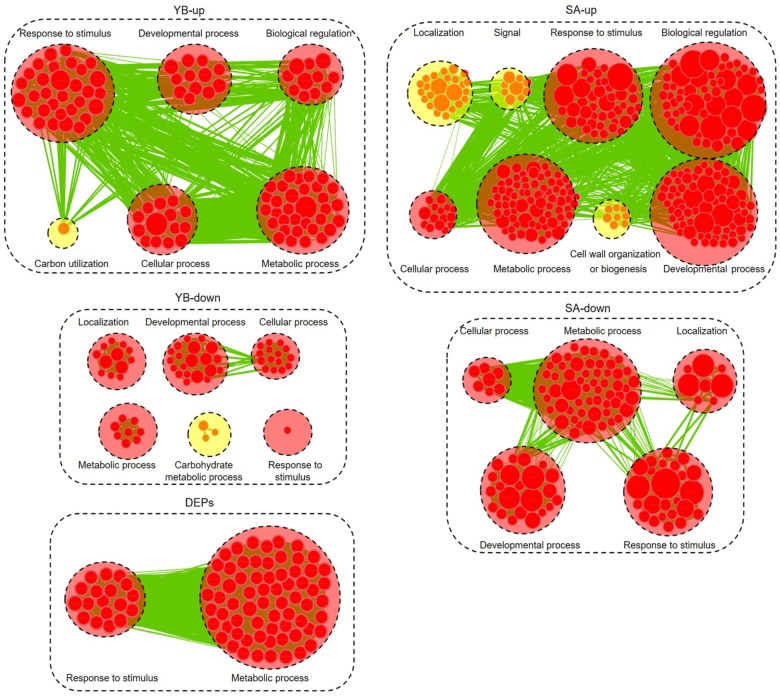

Gene Ontology (GO) Analysis of DEGsand DEPs

We further analyzed the up- and down-regulated DEGs (| log2 ratio| > 1) at the YB and SA stages and total DEPs between Shaan2A and Shaan2B using Cytoscape BiNGO and visualized the functional enrichment with Cytoscape EnrichmentMap. As shown in Figure 8, YB-up, YB-down, SA-up, SA-down, and DEPs generated 102, 59, 300, 117, and 85 nodes, respectively. These nodes were classified into different categories. Interestingly, the common GO terms among these stages were “response to stimulus” and “metabolic process,” which might largely be due to the toxic action of the sterility gene in mitochondria disrupting the balance of metabolic processes in Shaan2A. Very importantly, nine categories associated with anther and pollen development were enriched among down-regulated DEGs at the YB stage: “androecium development,” “anther development,” “microsporogenesis,” “pollen development,” “pollen exine formation,” “pollen wall assembly,” “sporopollenin biosynthetic process,” “stamen development,” and “tapetal layer development.” This indicates that anther and pollen development were disordered at the YB stage in Shaan2A, consistent with the cytological observations mentioned above. Expression levels of the genes in these GO categories at the YB stage are given in Supplementary Table S5. For example, three copies of CYP703A2 were remarkably down-regulated (BnaA10g00600D, log2 ratio = −13.53; BnaC05g00670D, log2 ratio = −13.30; BnaCnng08630D, log2 ratio = −10.29); this gene is expressed in developing anthers, and knockout lines display a partial male sterile phenotype in Arabidopsis (Morant et al., 2007). Two copies of LESS ADHESIVE POLLEN 6 (LAP6) were also significantly down-regulated (BnaA04g21720D, log2 ratio = −9.50; BnaC04g45570D, log2 ratio = −12.63); this gene is transiently and specifically expressed in tapetal cells during pollen development in Arabidopsis, and the mutants show defective pollen exine (Kim et al., 2011).

FIGURE 8.

Biological process analysis of DEGs and DEPs. GO modules enriched by up- and down-regulated DEGs and DEPs visualized using Cytoscape EnrichmentMap. Yellow and red circles show different and common biological processes between up- and down-regulated DEGs, respectively. The related GO categories are circled with a black dashed ring.

Transcription Factor Analysis

Transcription factors play key roles in multiple biological processes. We identified 349 up-regulated and 464 down-regulated TFs in Shaan2A compared to Shaan2B at the YB stage, and 867 up-regulated and 596 down-regulated TFs at the SA stage (P < 0.05, Supplementary Table S6). Most genes belonging to “bHLH,” “C2H2,” “MADS,” and “MYB” TF families were down-regulated in Shaan2A at the YB stage. Interestingly, 110 TFs were only expressed in Shaan2B at this stage. These included two copies of DYT1 (a putative bHLH TF), predicted to play a key role in a putative regulatory network model for Arabidopsis anther development, and three copies of MYB80, the downstream gene of DYT1 (Feng et al., 2012; Cui et al., 2016). Further, some TFs reported to be key regulators of anther differentiation were down-regulated at the YB stage.

Genes Related to Early Anther Differentiation

During early anther differentiation, SPL, which is activated by AG, together with its down-stream genes, specifies archesporial cells in Arabidopsis before meiosis (Feng and Dickinson, 2007). The expression levels of 23 of these genes at the YB stage are shown in Supplementary Table S7, with 12 of them significantly differentially expressed between Shaan2A and Shaan2B. Among these, three genes were slightly up-regulated in Shaan2A: ER, GRF, and ERL2. Interestingly, the eight down-regulated genes showed large log2 ratios for expression level; for example, two copies of SPL (BnaA01g16350D, log2 ratio = −2.72; BnaC01g19500D, log2 ratio = −2.66), ROXY2 (BnaA02g01990D, log2 ratio = −4.72), four copies of AMS (BnaA03g39400D, log2 ratio = −13.00; BnaA07g03340D, log2 ratio = −9.00; BnaC03g46740D, log2 ratio = −10.33; BnaC07g05950D, log2 ratio = −11.92), and two copies of MS1 were only expressed in Shaan2B. There were 11 genes with no significant difference in expression between Shaan2A and Shaan2B or no expression in either the sterile or maintainer lines, for instance, AG, SPL8, TPD1, and SERK1/2, indicating that they might not participate in Shaan2A CMS.

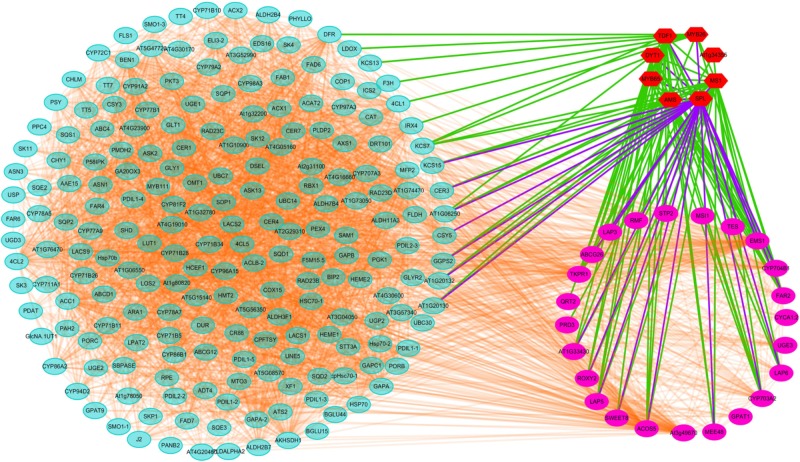

Interaction Analysis for Candidate Genes

Transcriptomic and proteomic analyses suggested that CMS in Shaan2A is controlled by a complex regulatory network. To further elucidate this mechanism, we investigated known and predicted interactions among candidate proteins corresponding to our DEGs and DEPs; for example, TFs associated with anther differentiation and genes belonging to the anther and pollen development GO categories mentioned above. Protein–protein interactions based on Arabidopsis orthologs were identified using STRING 10.0 and visualized using Cytoscape 3.6.1, and an interaction network associated with anther development was constructed. As shown in Figure 9, this network contained 236 nodes. Interestingly, TFs down-regulated at the YB stage showed interactions with many other proteins. For instance, SPL interacted with 26 targets including MYB65, TDF1, ROXY2, AMS, and MS1, DYT1 interacted with 19 targets including ABCG26, LAP3, LAP5, AT1G33430, and CYP704B1, and MYB65 interacted with seven targets including SPL, AMS, MS1, and DYT1. Therefore, these TFs and their target proteins might form a complex network for regulating anther differentiation and pollen development in Shaan2A CMS.

FIGURE 9.

Interaction analysis of candidate proteins. Red nodes represent TFs related to early anther differentiation. Rose red nodes represent proteins in the nine GO categories of anther and pollen development. Light blue nodes represent proteins in the significantly enriched pathways identified by KEGG or MapMan analysis.

Discussion

In recent years, CMS has been widely studied by transcriptomic and proteomic analysis in different species, including onion (Yuan et al., 2018), cotton (Suzuki et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2018), maize (Li et al., 2017), and rapeseed (An et al., 2014; Du et al., 2016). These studies revealed that cotton CMS-D8 lines have reduced ability to eliminate ROS (Yang et al., 2018), secretion and translocation of sporopollenin precursors is significantly down-regulated in cabbage R2P2CMS (Xing et al., 2018), and significant DEGs in rapeseed SaNa-1A CMS and pol CMS mostly participate in protein synthesis and metabolic pathways (An et al., 2014; Du et al., 2016). In the present study, DEGs were enriched in “protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum,” “carbon metabolism,” and “fatty acid degradation” categories at the YB stage, and “starch and sucrose metabolism,” “porphyrin and chlorophyll metabolism,” and “carbon metabolism” categories at the SA stage. Moreover, DEPs indicated that functional processes of “genetic information processing,” “carbohydrate metabolism,” “energy metabolism,” and “amino acid metabolism” were disordered in Shaan2A.

Shaan2A Is Defective in Early Anther Differentiation

Tapetum cells in a sterile onion CMS line begin to degrade from the tetrad stage and microspores start to abort, while degradation in its maintainer line is not observed until the microspore stage (Yuan et al., 2018). Fertile and sterile cotton anthers show differences at the meiotic stage, but no obvious variations before the stage when the microsporocytes and four anther wall cell layers are formed (Yang et al., 2018). In the C-type CMS of maize, no significant differences in microspores are observed between fertile and sterile plants until the mononuclear stage (Li et al., 2017). Although the pollen sac in the SaNa-1A CMS line forms normally, tapetum cells develop vacuolation at the microsporocyte and tetrad stages compared with the maintainer line (Du et al., 2016). In this study, the anther epidermis, endothecium, middle wall layers, tapetum, and sporogenous cells could not be clearly distinguished in Shaan2A by paraffin section observation (Figure 2). TEM analysis also revealed fewer mitochondria in the anther wall cells of Shaan2A than of Shaan2B, and the lamella structure of chloroplasts in Shaan2A anther wall cells was obviously abnormal (Figure 3). In contrast to Shaan2B, there was no difference between epidermis and tapetum cells in Shaan2A at the late stage of anther differentiation (Figure 3). Hence, we deduce that defective differentiation of anther wall cells and sporogenous cells in Shaan2A results in male sterility.

Shaan2A Anther Cells Have Damaged Mitochondria

Cytoplasmic male sterility is a maternally inherited trait resulting from the interaction of a nuclear fertility restoring gene (Rf) and a mitochondrial CMS gene (Horn et al., 2014; Yamagishi and Bhat, 2014). A few CMS-associated genes have been reported, for example, orf224 in pol CMS (L’Homme and Brown, 1993; Menassa et al., 1999) and orf138 in Ogu CMS (Duroc et al., 2005). However, the sterility gene in the Shaan2A mitochondrial genome has not been identified. The mitochondrion is a crucial organelle for metabolic pathways such as respiratory electron transfer, ATP synthesis, and the TCA cycle (Reichert and Neupert, 2004; Logan, 2006). As well as the number of mitochondria in Shaan2A anthers being less than that in Shaan2B, most DEGs associated with the “mitochondrial electron transport/ATP synthesis pathway” and “TCA cycle” were obviously down-regulated at the YB and SA stages in Shaan2A anthers (Figure 5), including some important genes such as Bnac04g22440D (CITRATE SYNTHASE 5, log2 ratio = −7.69 at YB stage), BnaC03g08060D (NAD(P)H DEHYDROGENASE B4, log2 ratio = −5.55 at YB stage), and BnaA05g17260D (AOX1a, log2 ratio = −2.34 at YB stage). Additionally, 15.2% DEPs were grouped into the “energy metabolism” functional category. It is interesting that AT4G11150 (a V-type proton-ATPase) and AT1G76030 (a nucleotide-binding subunit of vacuolar ATPase) were both up-regulated in Shaan2A anthers compared to Shaan2B anthers; if defective mitochondria in Shaan2A do not produce enough energy to meet the needs for rapid anther growth, these ATPases might be up-regulated to rescue the energy metabolism in the sterile anthers. As the sterility gene in Shaan2A is unknown, the mechanism by which it functions and induces a series of response in mitochondria will need further study.

Shaan2A Anther Cells Have Injured Chloroplasts

The abundance of starch in chloroplasts is necessary for microspore development and is a crucial feature of fertile pollen (Du et al., 2016). Most studies of male sterility in plants have identified “carbon metabolism” as disordered (Cheng et al., 2013; Li et al., 2015, 2016; Du et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2018; Yuan et al., 2018). Interestingly, the lamella structure of chloroplasts in Shaan2A anther wall cells was obviously abnormal. Most DEGs involved in “carbon metabolism,” “light reactions,” “photorespiration,” and “Calvin cycle” at the YB and SA stages (Figure 5 and Supplementary Table S3) and in “starch and sucrose metabolism” and “porphyrin and chlorophyll metabolism” at the SA stage were up-regulated (Supplementary Table S2). However, proteomic analysis revealed that the 12 DEPs grouped into “carbohydrate metabolism” were mostly down-regulated, except for ATCG00490, (ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase large subunit, encoded by a chloroplast gene) and AT3G62030 (a nuclear-encoded chloroplast stromal cyclophilin CYP20-3, also known as ROC4). Despite many carbon metabolism related pathways being identified by up-regulated genes, chloroplasts of Shaan2A contained fewer starch grains than those in Shaan2B (Figure 3). Therefore, we speculate that high expression of many genes related to carbon metabolism is triggered by the injured chloroplast structure in Shaan2A. However, this up-regulation cannot balance the carbon metabolism in cells, which might be affected by the sterility gene. The direct or indirect mechanism by which the sterility gene impacts chloroplasts requires further study.

Genes Involved in Early Anther Differentiation Are Down-Regulated at the YB Stage

SPL functions downstream of AG, specifying the identity, position, and number of archesporial cells in the anther L2 layer (Schiefthaler et al., 1999; Yang et al., 1999). We identified two copies of SPL that were down-regulated in Shaan2A compared with Shaan2B, while three copies of AG were not significantly expressed (Supplementary Table S7). We therefore presume that SPL is the first gene repressed by the sterility gene in the mitochondrion. Furthermore, SPL was predicted to interact with 26 targets (Figure 9). These include TFs such as MYB65, ROXY2, AMS, MS1, and DYT1, which were also obviously down-regulated in Shaan2A (Supplementary Table S7). In Arabidopsis, MYB33 and MYB65 share high sequence similarity. The myb33 myb65 double mutant has a deficiency in anther development, with hypertrophied tapetum at the pollen mother cell stage and aborted microspores before meiosis; the single mutant shows no phenotype, implying that MYB65 and MYB33 are functionally redundant (Millar, 2005). In B. napus, we only identified putative orthologs of AtMYB65; however, three copies of BnMYB65 were significantly down-regulated. ROXY1 and ROXY2 together control anther development in Arabidopsis, and single mutants produce normal anthers; however, double mutants are sterile owing to defects in early lobe differentiation (Xing and Zachgo, 2008). In the present study, two copies of ROXY2 showed significant down-regulation in Shaan2A compared with Shaan2B (Supplementary Table S7). In addition, four copies of AMS, two copies of MS1, and three copies of DYT1 exhibited large log2 ratios of down-regulation in Shaan2A (Supplementary Table S7); all of these are located downstream of SPL and essential for anther and pollen development in Arabidopsis (Wilson et al., 2001; Feng and Dickinson, 2007; Feng et al., 2012; Ferguson et al., 2017).

SPL was also predicted to interact with ABCG26, MEE48, LAP5, LAP6, ACOS5, EMS1, and other proteins (Figure 9). In Arabidopsis, ABCG26 is an ATP binding cassette (ABC) transporter localized to the plasma membrane and endoplasmic reticulum that mediates trafficking of hydroxycinnamoyl spermidines and polyketides needed for sporopollenin formation (Quilichini et al., 2010, 2014). Maternal Effect Embryo Arrest 48 (MEE48) is related to morphogenesis and development (Chakraborty et al., 2015). LAP5 and LAP6 catalyze condensation of malonyl-CoA units with CoA ester starter molecules to generate various natural products, and are required for sporopollenin biosynthesis and pollen development (Kim et al., 2011). The acyl-CoA synthetase 5 (ACOS5) gene encodes a fatty acyl-CoA synthetase that plays a key role in sporopollenin biosynthesis and exine formation (de Azevedo Souza et al., 2009). EMS1 encodes a putative LRR receptor protein kinase (LRR-RPK) controlling reproductive cell fates in anthers (Canales et al., 2002; Zhao et al., 2002). Interestingly, in B. napus, six copies of MEE48, seven copies of LAP5, two copies of LAP6, and two copies of ACOS5 showed high log2 ratios of down-regulation in Shaan2A or were only expressed in Shaan2B, and two copies of EMS1 also displayed lower expression in Shaan2A than in Shaan2B (Supplementary Tables S5, S7). These genes were also predicted to interact with many other genes (Figure 9). Taken together, we propose that after the male sterility signal from the mitochondrion is transferred to the nucleus, it initiates suppression of SPL expression resulting in down-regulation of its downstream genes, which form a huge and complicated regulatory network for anther differentiation in Shaan2A. However, the mechanism underlying this network requires further research.

Data Availability

Transcriptomic raw reads were submitted to the SRA (Sequence Read Archive of NCBI) database with accession number PRJNA502996.

Author Contributions

ML and HW conceived and designed the experiments. LN and ZL performed the experiments and analyzed the data. DL provided the Shaan2A and Shaan2B materials. YL, WZ, HC, and LM helped to analyze the data. LN and ML wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Research Core Facilities for Life Science for qRT-PCR experiments.

Funding. This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program (2016YFD0101300), the National Science Foundation of China (31471532), the New Century Talents Support Program by the Ministry of Education of China (NCET110172), and the Science and Technology Plan Project of Yangling Demonstration Zone of China (2017NY-20).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2019.00252/full#supplementary-material

TEM observation of anther wall cells in Shaan2A and Shaan2B. (A) Overview of anther wall cells in 1 mm buds of Shaan2A. (B) Overview of anther wall cells in 2 mm buds of Shaan2A. (C) Overview of anther wall cells in 3 mm buds of Shaan2A. (D) Overview of anther wall cells in 1 mm buds of Shaan2B. (E) Overview of anther wall cells in 2 mm buds of Shaan2B. (F) Overview of anther wall cells in 3 mm buds of Shaan2B. E, epidermis; En, endothecium; ML, middle layer; T, tapetum; MMC, microspore mother cells.

Validation of DEGs by qRT-PCR. (A) Result from qRT-PCR. (B) Result from RNA-seq. Numbers are log2(X)-normalized ratio values. Red represents higher gene expression levels. Green corresponds to lower gene expression levels. Blocks without a numerical value indicate that gene expression was not significantly detected by RNA-seq.

Primers used in qRT-PCR.

Enriched KEGG pathways identified from DEGs at the YB and SA stages. Pathways were considered enriched at corrected P < 0.05.

Detailed information on metabolic pathways from MapMan analysis.

Correlation analysis between DEGs and DEPs. Y represents positive correlation between DEGs and DEPs. N represents negative correlation between DEGs and DEPs.

Expression levels of genes in the nine GO categories associated with anther and pollen development at the YB stage.

Transcription factors identified at the YB and SA stages.

Expression levels of genes related to early anther differentiation at the YB stage.

References

- An H., Yang Z., Yi B., Wen J., Shen J., Tu J., et al. (2014). Comparative transcript profiling of the fertile and sterile flower buds of pol CMS in B. napus. BMC Genomics 15:258. 10.1186/1471-2164-15-258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canales C., Bhatt A. M., Scott R., Dickinson H. (2002). EXS, a putative LRR receptor kinase, regulates male germline cell number and tapetal identity and promotes seed development in Arabidopsis. Curr. Biol. 12 1718–1727. 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)01151-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty N., Sharma P., Kanyuka K., Pathak R. R., Choudhury D., Hooley R., et al. (2015). G-protein α-subunit (GPA1) regulates stress, nitrate and phosphate response, flavonoid biosynthesis, fruit/seed development and substantially shares GCR1 regulation in A. thaliana. Plant Mol. Biol. 89 559–576. 10.1007/s11103-015-0374-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalhoub B., Denoeud F., Liu S., Parkin I. A., Tang H., Wang X., et al. (2014). Early allopolyploid evolution in the post-Neolithic Brassica napus oilseed genome. Science 345 950–953. 10.1126/science.1253435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Liu Y. G. (2014). Male sterility and fertility restoration in crops. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 65 579–606. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050213-040119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y., Wang Q., Li Z., Cui J., Hu S., Zhao H., et al. (2013). Cytological and comparative proteomic analyses on male sterility in Brassica napus L. induced by the chemical hybridization agent monosulphuron ester sodium. PLoS One 8:e80191. 10.1371/journal.pone.0080191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow K. S., Singh D. P., Walker A. R., Smith A. G. (1998). Two different genes encode ferrochelatase in Arabidopsis: mapping, expression and subcellular targeting of the precursor proteins. Plant J. 15 531–541. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1998.00235.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J., You C., Zhu E., Huang Q., Ma H., Chang F. (2016). Feedback regulation of DYT1 by interactions with downstream bHLH factors promotes DYT1 nuclear localization and anther development. Plant Cell 28 1078–1093. 10.1105/tpc.15.00986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Azevedo Souza C., Kim S. S., Koch S., Kienow L., Schneider K., McKim S. M., et al. (2009). A novel fatty Acyl-CoA synthetase is required for pollen development and sporopollenin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21 507–525. 10.1105/tpc.108.062513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du K., Liu Q., Wu X., Jiang J., Wu J., Fang Y., et al. (2016). Morphological structure and transcriptome comparison of the cytoplasmic male sterility line in Brassica napus (SaNa-1A) derived from somatic hybridization and its maintainer line SaNa-1B. Front. Plant Sci. 7:1313. 10.3389/fpls.2016.01313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duroc Y., Gaillard C., Hiard S., Defrance M., Pelletier G., Budar F. (2005). Biochemical and functional characterization of ORF138, a mitochondrial protein responsible for Ogura cytoplasmic male sterility in Brassiceae. Biochimie. 87 1089–1100. 10.1016/j.biochi.2005.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan T., Roling L., Meiers A., Brings L., Ortega-Rodés P., Hedtke B., et al. (2018). Complementation studies of the Arabidopsis fc1 mutant substantiate essential functions of ferrochelatase 1 during embryogenesis and salt stress. Plant Cell Environ. 42 618–632. 10.1111/pce.13448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng B., Lu D., Ma X., Peng Y., Sun Y., Ning G., et al. (2012). Regulation of the Arabidopsis anther transcriptome by DYT1 for pollen development. Plant J. 72 612–624. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05104.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X., Dickinson H. G. (2007). Packaging the male germline in plants. Trends Genet. 23 503–510. 10.1016/j.tig.2007.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson A. C., Pearce S., Band L. R., Yang C., Ferjentsikova I., King J., et al. (2017). Biphasic regulation of the transcription factor ABORTED MICROSPORES, AMS is essential for tapetum and pollen development in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 213 778–790. 10.1111/nph.14200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu T. D. (1981). Production and research of rapeseed in the people’s republic of China. Eucarpia Cruciferae Newsletter 6 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Fu T. D. (1995). Breeding and Utilization of Rapeseed Hybrids. Wuhan: Hubei Science and Technology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gan L., Zhang C., Wang X., Wang H., Long Y., Yin Y., et al. (2013). Proteomic and comparative genomic analysis of two Brassica napus lines differing in oil content. J. Proteome Res. 12 4965–4978. 10.1021/pr4005635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hord C. L. H. (2006). The BAM1/BAM2 receptor-like kinases are important regulators of Arabidopsis early anther development. Plant Cell 18 1667–1680. 10.1105/tpc.105.036871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn R., Gupta K. J., Colombo N. (2014). Mitochondrion role in molecular basis of cytoplasmic male sterility. Mitochondrion 19 198–205. 10.1016/j.mito.2014.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones H., Clarke A. (1943). Inheritance of male sterility in the onion and the production of hybrid seed. J. Proc. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 43 189–194. [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. S., Grienenberger E., Lallemand B., Colpitts C. C., Kim S. Y., Souza C. D. A., et al. (2011). LAP6/POLYKETIDE SYNTHASE A and LAP5/POLYKETIDE SYNTHASE B encode hydroxyalkyl α-pyrone synthases required for pollen development and sporopollenin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 22 4045–4066. 10.1105/tpc.110.080028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laser K. D., Larsten N. R. (1972). Anatomy and cytology of microsporogenesis in cytoplasmic male sterile angiosperms. Bot. Rev. 38 425–454. 10.1007/BF02860010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Lee B. H., Jung J., Park S. K., Song J. T., Kim J. H. (2018). Growth-regulating factor and GRF-interacting factor specify meristematic cells of gynoecia and anthers. Plant Physiol. 176 717–729. 10.1104/pp.17.00960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- L’Homme Y., Brown G. G. (1993). Organizational differences between cytoplasmic male sterile and male fertile Brassica mitochondrial genomes are confined to a single transposed locus. Nucleic Acids Res. 21 1903–1909. 10.1093/nar/21.8.1903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Zhao Z., Liu Y., Liang B., Guan S., Lan H., et al. (2017). Comparative transcriptome analysis of isonuclear-alloplasmic lines unmask key transcription factor genes and metabolic pathways involved in sterility of maize CMS-C. PeerJ. 5:e3408. 10.7717/peerj.3408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D. R. (1980). Report on three-lines breeding in Brassica napus. Shaanxi J. Agric. Sci. 1 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Li D. R., Tian J. H. (2015). Role and function of cultivar Qinyou 2 in rapeseed hybrid breeding and production in China. Chin. J. Oil Crop Sci. 37 902–906. [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Ding X., Han S., He T., Zhang H., Yang L., et al. (2016). Differential proteomics analysis to identify proteins and pathways associated with male sterility of soybean using iTRAQ-based strategy. J. Proteomics 138 72–82. 10.1016/j.jprot.2016.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Bonawitz N. D., Weng J. K., Chapple C. (2010). The growth reduction associated with repressed lignin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana is independent of flavonoids. Plant Cell 22 1620–1632. 10.1105/tpc.110.074161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Cheng Y., Cui J., Zhang P., Zhao H., Hu S. (2015). Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals carbohydrate and lipid metabolism blocks in Brassica napus L. male sterility induced by the chemical hybridization agent monosulfuron ester sodium. BMC Genomics 16:206. 10.1186/s12864-015-1388-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian H., Li X., Liu Z., He Y. (2013). HYL1 is required for establishment of stamen architecture with four microsporangia in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 64 3397–3410. 10.1093/jxb/ert178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Zhang G., Wang J., Li J., Song Y., Qiao L., et al. (2018). Chemical hybridizing agent SQ-1-induced male sterility in Triticum aestivum L., a comparative analysis of the anther proteome. BMC Plant Biol. 18:7. 10.1186/s12870-017-1225-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan D. C. (2006). The mitochondrial compartment. J. Exp. Bot. 57 1225–1243. 10.1093/jxb/erj151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohmann J. U., Hong R. L., Hobe M., Busch M. A., Parcy F., Simon R., et al. (2001). A molecular link between stem cell regulation and floral patterning in Arabidopsis. Cell 105 793–803. 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00384-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menassa R., L’Homme Y., Brown G. G. (1999). Post-transcriptional and developmental regulation of a CMS-associated mitochondrial gene region by a nuclear restorer gene. Plant J. 17 491–499. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1999.00397.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng J., Wang L., Wang J., Zhao X., Cheng J., Yu W., et al. (2018). Methionine adenosyltransferase 4 mediates DNA and histone methylation. Plant Physiol. 177 652–670. 10.1104/pp.18.00183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao L. Y., Zhang L. B., Raboanatahiry N., Lu G., Zhang X., Xiang J., et al. (2016). Transcriptome analysis of stem and globally comparison with other tissues in Brassica napus. Front. Plant Sci. 7:1403. 10.3389/fpls.2016.01403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar A. A. (2005). The Arabidopsis GAMYB-Like genes, MYB33 and MYB65, are microRNA-regulated genes that redundantly facilitate anther development. Plant Cell 17 705–721. 10.1105/tpc.104.027920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morant M., Jorgensen K., Schaller H., Pinot F., Moller B. L., Werck-Reichhart D., et al. (2007). CYP703 is an ancient cytochrome P450 in land plants catalyzing in-chain hydroxylation of lauric acid to provide building blocks for sporopollenin synthesis in pollen. Plant Cell 19 1473–1487. 10.1105/tpc.106.045948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning L. Y., Lin Z. W., Gu J. W., Gan L., Li Y. H., Wang H., et al. (2018). The initial deficiency of protein processing and flavonoids biosynthesis were the main mechanisms for the male sterility induced by SX-1 in Brassica napus. BMC Genomics 19:806. 10.1186/s12864-018-5203-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura H. (1968). Studies on the male sterility in Japanese radish with special reference to the utilization of this sterility towards the practical raising of hybrid seed. Mem. Fac. Agric. Kagosh. Univ. 6 39–78. [Google Scholar]

- Quilichini T. D., Friedmann M. C., Samuels A. L., Douglas C. J. (2010). ATP-Binding cassette transporter G26 is required for male fertility and pollen exine formation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 154 678–690. 10.1104/pp.110.161968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quilichini T. D., Samuels A. L., Douglas C. J. (2014). ABCG26-mediated polyketide trafficking and hydroxycinnamoyl spermidines contribute to pollen wall exine formation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 26 4483–4498. 10.1105/tpc.114.130484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radoev M., Becker H. C., Ecke W. (2008). Genetic analysis of heterosis for yield and yield components in rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) by quantitative trait locus mapping. Genetics 179 1547–1558. 10.1534/genetics.108.089680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichert A. S., Neupert W. (2004). Mitochondriomics or what makes us breathe. Trends Genet. 20 555–562. 10.1016/j.tig.2004.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander P. M., Bui A. Q., Weterings K., Mcintire K. N., Hsu Y. C., Lee P. Y., et al. (1999). Anther developmental defects in Arabidopsis thaliana male-sterile mutants. Sex. Plant Reprod. 11 297–322. 10.1007/s004970050158 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schiefthaler U., Balasubramanian S., Sieber P., Chevalier D., Wisman E., Schneitz K. (1999). Molecular analysis of NOZZLE, a gene involved in pattern formation and early sporogenesis during sex organ development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96 11664–11669. 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnable P. S., Wise R. P. (1998). The molecular basis of cytoplasmic male sterility and fertility restoration. Trends Plant Sci. 3 175–180. 10.1093/jxb/erx239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiga T., Baba S. (1971). Cytoplasmic male sterility in rape plant, Brassica napus L. Jap. J. Breed. 21 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Sieber P. (2004). Organ polarity in Arabidopsis. NOZZLE physically interacts with members of the YABBY family. Plant Physiol. 135 2172–2185. 10.1104/pp.104.040154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H., Rodriguez-Uribe L., Xu J., Zhang J. (2013). Transcriptome analysis of cytoplasmic male sterility and restoration in CMS-D8 cotton. Plant Cell Rep. 32 1531–1542. 10.1007/s00299-013-1465-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson Z. A., Morroll S. M., Dawson J., Swarup R., Tighe P. J. (2001). The Arabidopsis male sterility1 (MS1) gene is a transcriptional regulator of male gametogenesis, with homology to the PHD-finger family of transcription factors. Plant J. 28 27–39. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2001.01125.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisén S., Gestwicki J. E. (2008). Identification of small molecules that modify the protein folding activity of heat shock protein 70. Anal. Biochem. 374 371–377. 10.1016/j.ab.2007.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G. Z., Xue H. W. (2010). Arabidopsis β-ketoacyl-[acyl carrier protein] synthase I is crucial for fatty acid synthesis and plays a role in chloroplast division and embryo development. Plant Cell 22 3726–3744. 10.1105/tpc.110.075564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing M., Sun C., Li H., Hu S., Lei L., Kang J. (2018). Integrated analysis of transcriptome and proteome changes related to the Ogura cytoplasmic male sterility in cabbage. PLoS One 13:e193462. 10.1371/journal.pone.0193462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing S., Zachgo S. (2008). ROXY1 and ROXY2, two Arabidopsis glutaredoxin genes, are required for anther development. Plant J. 53 790–801. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03375.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagishi H., Bhat S. R. (2014). Cytoplasmic male sterility in Brassicaceae crops. Breed. Sci. 64 38–47. 10.1270/jsbbs.64.38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Wu Y., Zhang M., Zhang J., Stewart J. M., Xing C. (2018). Transcriptome, cytological and biochemical analysis of cytoplasmic male sterility and maintainer line in CMS-D8 cotton. Plant Mol. Biol. 97 537–551. 10.1007/s11103-018-0757-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W. C., Ye D., Xu J., Sundaresan V. (1999). The SPOROCYTELESS gene of Arabidopsis is required for initiation of sporogenesis and encodes a novel nuclear protein. Genes Dev. 13 2108–2117. 10.1101/gad.13.16.2108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi B., Zeng F., Lei S., Chen Y., Yao X., Zhu Y. (2010). Two duplicate CYP704B1-homologous genes BnMs1 and BnMs2 are required for pollen exine formation and tapetal development in Brassica napus. Plant J. 63 925–938. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04289.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Q., Song C., Gao L., Zhang H., Yang C., Sheng J. (2018). Transcriptome de novo assembly and analysis of differentially expressed genes related to cytoplasmic male sterility in onion. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 125 35–44. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2018.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao D. Z., Wang G. F., Speal B., Ma H. (2002). The excess microsporocytes1 gene encodes a putative leucine-rich repeat receptor protein kinase that controls somatic and reproductive cell fates in the Arabidopsis anther. Genes Dev. 16 2021–2031. 10.1101/gad.997902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z. F., Dun X., Xia S., Shi D., Qin M., Yi B., et al. (2012). BnMs3 is required for tapetal differentiation and degradation, microspore separation, and pollen-wall biosynthesis in Brassica napus. J. Exp. Bot. 63 2041–2058. 10.1093/jxb/err405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

TEM observation of anther wall cells in Shaan2A and Shaan2B. (A) Overview of anther wall cells in 1 mm buds of Shaan2A. (B) Overview of anther wall cells in 2 mm buds of Shaan2A. (C) Overview of anther wall cells in 3 mm buds of Shaan2A. (D) Overview of anther wall cells in 1 mm buds of Shaan2B. (E) Overview of anther wall cells in 2 mm buds of Shaan2B. (F) Overview of anther wall cells in 3 mm buds of Shaan2B. E, epidermis; En, endothecium; ML, middle layer; T, tapetum; MMC, microspore mother cells.

Validation of DEGs by qRT-PCR. (A) Result from qRT-PCR. (B) Result from RNA-seq. Numbers are log2(X)-normalized ratio values. Red represents higher gene expression levels. Green corresponds to lower gene expression levels. Blocks without a numerical value indicate that gene expression was not significantly detected by RNA-seq.

Primers used in qRT-PCR.

Enriched KEGG pathways identified from DEGs at the YB and SA stages. Pathways were considered enriched at corrected P < 0.05.

Detailed information on metabolic pathways from MapMan analysis.

Correlation analysis between DEGs and DEPs. Y represents positive correlation between DEGs and DEPs. N represents negative correlation between DEGs and DEPs.

Expression levels of genes in the nine GO categories associated with anther and pollen development at the YB stage.

Transcription factors identified at the YB and SA stages.

Expression levels of genes related to early anther differentiation at the YB stage.

Data Availability Statement

Transcriptomic raw reads were submitted to the SRA (Sequence Read Archive of NCBI) database with accession number PRJNA502996.