Abstract

The sleep-wake cycle regulates interstitial fluid (ISF) and cerebrospinal (CSF) levels of amyloid-β (Aβ) that accumulates in Alzheimer disease (AD) and chronic sleep deprivation (SD) increases Aβ plaques. However, tau not Aβ accumulation appears to drive AD neurodegeneration. Therefore, we tested whether ISF/CSF tau and tau seeding/spreading was influenced by the sleep-wake cycle and SD. Mouse ISF tau was increased ~90% during normal wakefulness vs. sleep and ~100% during SD. Human CSF tau also increased over 50% during SD. In a tau seeding and spreading model, chronic SD increased tau pathology spreading. Chemogenetically-driven wakefulness in mice also significantly increased both ISF Aβ and tau. Thus, the sleep-wake cycle regulates ISF tau and sleep deprivation increases ISF and CSF tau as well as tau pathology spreading.

One sentence summary:

Brain interstitial fluid tau is increased during wakefulness and with sleep deprivation, which is relevant for Alzheimer disease and other tauopathies.

Tau is an abundant cytoplasmic protein in neurons. In diseases called tauopathies that include Alzheimer disease (AD), progressive supranuclear palsy, Pick’s disease, and chronic traumatic encephalopathy, tau becomes hyperphosphorylated and aggregates in structures such as neurofibrillary tangles and neuropil threads (1). Tau aggregation in the brain significantly correlates with neuronal and synaptic loss (2). There is substantial evidence that once tau aggregation occurs, it can spread from one synaptically connected region to another (3–7).

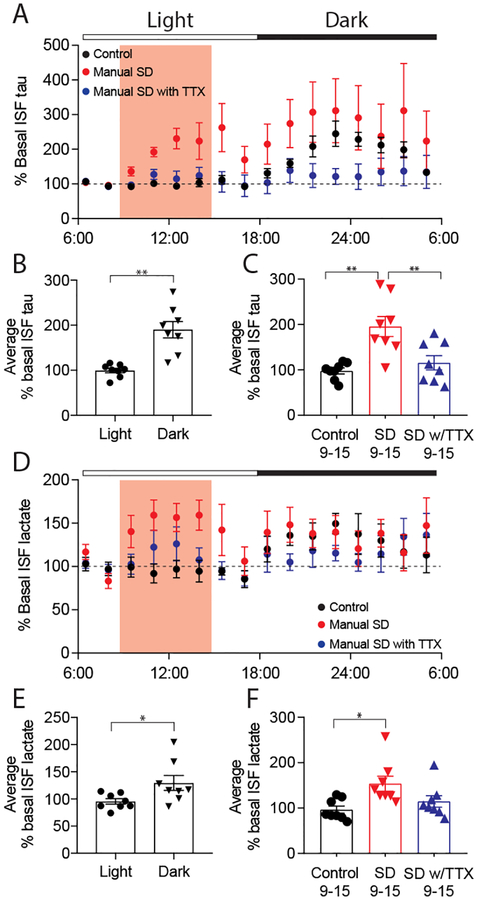

While tau is predominantly cytoplasmic, it is normally released by neurons into the extracellular space. This release is increased by excitatory neuronal activity (8, 9). When neuronal activity is increased chronically, it can increase tau propagation and pathology (10). As neuronal synaptic strength/connectivity is higher during wakefulness than during sleep (11, 12), we asked whether tau levels in the brain interstitial fluid (ISF) varied with the sleep-wake cycle. We measured tau levels in the hippocampal ISF of wild-type mice. ISF tau levels were low during the light period when, in our experience, wild-type mice generally sleep ~60% of the time. Following the transition to the dark period, when we have observed mice are awake ~70% of the time, ISF tau levels increased almost 2-fold (Fig. 1A, B, table S1, S3). Neuronal activity directly regulates lactate concentration in vivo (12, 13) and like ISF tau, ISF lactate was also higher during wakefulness and lower during sleep (Fig. 1D, E) as previously observed (12, 14). The change in ISF tau between light and dark (~90%) is greater than what we have previously observed with ISF Aβ (~30%) (15). Given this change, we asked whether acute sleep deprivation alters ISF tau. Three hours after the beginning of the light period, mice were kept awake by manual stimulation. Sleep deprivation induced a significant 2-fold increase in ISF tau (Fig. 1A, C, table S1, S3). This increase was paralleled by an increase in ISF lactate (Fig. 1D, F). In mice subjected to sleep deprivation during which neuronal activity was attenuated by infusion of tetrodotoxin (TTX) via reverse microdialysis, there was no increase in ISF tau or lactate (Fig. 1A, C, D, F, table S1, S3).

Fig. 1.

ISF tau exhibits diurnal fluctuation and increases following manual sleep deprivation (SD) but not in the presence of TTX. (A) ISF tau levels normalized to baseline (06:00–09:00) over the 24-hour analysis period. Manual SD and TTX infusion occurred from 09:00–15:00 (shaded), control animals were undisturbed. (B) Average ISF tau is significantly increased during dark (wake) compared to light (sleep) in control animals, demonstrating diurnal fluctuation (n=8, paired t-test). (C) Average ISF tau (normalized to baseline) during SD (09:00–15:00) was significantly increased in sleep-deprived mice compared to controls or mice with SD in the presence of TTX (n=8, One-Way ANOVA p=0.007, Bonferroni post-hoc). (D) ISF lactate over the 24-hour analysis period. (E) As with ISF tau, average ISF lactate was significantly increased during dark compared to light in control animals and (F) increased during SD (n=8, (E) paired t-test (F) Kruskal-Wallis. All data represent mean ± SEM. All mice 3–5 months, all conditions: 3F, 5M. *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

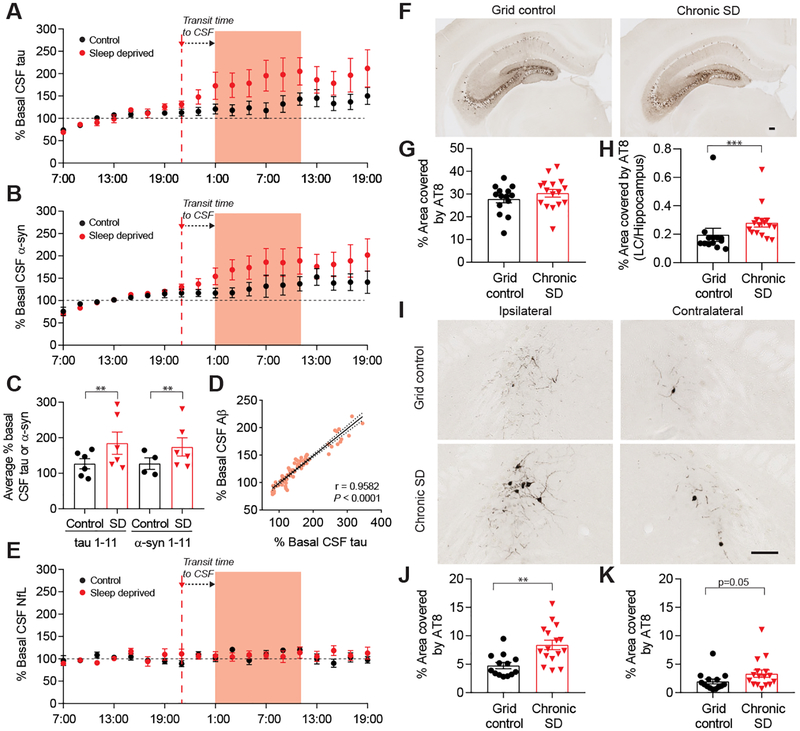

Since sleep deprivation increased ISF tau in the mouse brain, we wondered whether similar changes would be seen in the CSF of humans. We recently studied CSF in a group of adults, 30–60 years of age, who were monitored with lumbar catheters during one night of normal sleep and one night of sleep deprivation, with sleep sessions randomized and separated in time (16). We found that sleep deprivation significantly increased CSF Aβ by 30% (16). Using samples collected from the same participants, we found that CSF tau was increased to an even greater extent by over 50% (Fig. 2A, C, table S2, S4) and CSF tau levels significantly correlated with CSF Aβ levels (Fig. 2D, fig. S1A–C). We also assessed three additional proteins: neuronal neurofilament light chain (NfL), synuclein, and astrocytic glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP). Interestingly, synuclein, a presynaptic protein whose levels are increased following neuronal activity (17), was increased by sleep deprivation (Fig. 2B, C, table S2, S4). Unlike tau and synuclein, there was no increase in NfL or GFAP in CSF following sleep deprivation, suggesting some specificity in sleep/protein level interaction (Fig. 2E, fig. S2, table S2, S4).

Fig. 2.

CSF tau levels increase and are correlated with Aβ in sleep-deprived human subjects and chronic SD in mice increases tau spreading. (A) Human CSF tau and (B) synuclein (α-syn) levels normalized to baseline (07:00–19:00). SD began at 21:00 and CSF compared from 01:00–11:00 (shaded). (C) Tau levels during SD are significantly increased by 51.5% and α-syn increased by 36.4% compared to undisturbed sleep (n=6 (tau), n=4–6 (α-syn)), GLMM, first-order autoregressive). (D) Total CSF Aβ is significantly correlated with CSF tau in control and SD conditions during the SD time period (n=6, Pearson’s correlation). (E) CSF NfL is unchanged by SD (n=6). (F) Ipsilateral hippocampal AT8 p-tau staining in grid control and chronic SD P301S male mice with unilateral hippocampal tau fibril injection. (G) SD does not alter p-tau staining in the ipsilateral hippocampus (n=14–16). (H) The ipsilateral LC/hippocampus AT8 ratio is increased in SD mice (n=13–16, Mann-Whitney). (I) AT8 staining in the LC of SD and control hippocampal-seeded P301S mice (scale bar (F, H): 125 μm). (J) p-Tau is significantly increased in the ipsilateral LC (n=13–16, unpaired t-test) and (K) trended towards an increase in the contralateral LC (n=14–16, Mann-Whitney) of SD compared to control animals. All data represent mean ± SEM. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Given these results, we next tested the potential effects of longer periods of sleep deprivation on tau seeding and spreading, a process believed to be mediated by extracellular tau (18). Recombinant P301S human tau fibrils were produced and injected unilaterally into the hippocampus of 8–9 week old P301S male mice, prior to the onset of tau pathology, as described (5). Two days later, mice were subjected to 28 days of sleep deprivation or control conditions. Sleep deprivation did not alter tau seeding in the hippocampus; however, it significantly increased tau spreading to a region of the brain synaptically connected to the hippocampus and involved in maintenance of wakefulness, the locus coeruleus (LC), as assessed by p-tau staining with the antibody AT8 (Fig. 2F–K). Increased AT8 positive staining was also observed in the entorhinal cortex (fig. S3C, D). We saw a similar significant increase in tau spreading in the LC in sleep-deprived mice with the anti-tau antibody MC1, which recognizes a conformationally abnormal tau epitope (fig. S4). We also separately subjected 7.5–10 week old P301S mice to 28 days of sleep deprivation or control conditions without injecting tau fibrils. There was very little AT8 positive p-tau staining in the LC that did not differ between groups, indicating that the increased staining in the LC after tau fibril injection and its further increase following sleep deprivation is due to spreading and not simply due to enhancement of the tau pathology that develops in these mice (fig. S3A, B). One possible explanation for why 28 days of sleep deprivation did not increase tau pathology in naïve, non-injected mice may relate to recent findings that soluble tau overexpression results in suppression of neuronal activity (19).

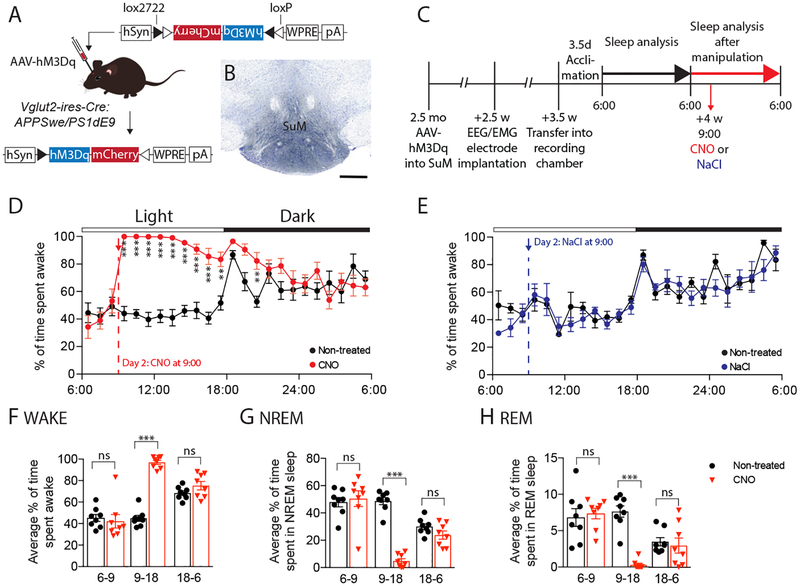

Physical sleep deprivation increases both Aβ and tau in ISF and CSF. Since physical sleep deprivation increases wakefulness but also influences additional processes such as sleep rebound, we wanted to specifically manipulate neuronal activity in a brain region that controls wakefulness. To do so, we expressed the excitatory chemogenetic system (hM3Dq), also known as designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs (DREADDs), in glutamatergic neurons (VGLUT2+) of the mouse supramammillary nucleus (SuM), a region recently established as a key arousal-promoting node. Administration of clozapine-N-oxide (CNO) to SuMVglut2-hM3Dq mice has been shown to result in sustained wakefulness for up to 12 hours (20). We bred APPswe/PS1δE9 transgenic mice that produce human Aβ (21), to mice that express Cre in excitatory glutamatergic VGLUT2-positive neurons (Vglut2-ires-Cre mice) (Fig 3A). We then placed stereotaxic injections of an AAV vector expressing Cre-dependent hM3Dq into the SuM at 2.5–3 months of age, resulting in expression of hM3Dq in glutamatergic cells of the SuM of transgenic Vglut2-ires-Cre:APPSwe/PS1δE9 mice (Fig. 3B), and monitored CNO wake-activated and control animals (Fig. 3C). Mice first underwent sleep-wake assessment by continuous EEG/EMG monitoring as well as in vivo microdialysis to measure Aβ and lactate for 24 hours undisturbed. Both groups were awake ~40% of the time during the light phase and ~65% during the dark phase (Fig. 3D, fig. S5). During the second 24-hour period, mice were injected i.p. with either CNO (0.3 mg/kg) or 0.9% NaCl (vehicle) three hours after the onset of the light period. Treatment of mice with CNO resulted in a marked increase in wakefulness for 9 hrs (over 95% wakefulness, hrs 1–5) and a significant decrease in NREM and REM sleep (Fig. 3D, F–H, fig. S5). In mice treated with vehicle, there was no effect on wakefulness, NREM, or REM sleep (Fig. 3E, fig. S5). Interestingly, there was no effect on sleep rebound. There was also no effect of CNO or its parent compound clozapine on wakefulness in non-AAV PBS-injected Vglut2-ires-Cre:APPSwe/PS1δE9 mice (fig. S6).

Fig. 3.

Chemogenetic (hM3Dq) activation of glutamatergic supramammillary neurons drives sustained wakefulness without inducing sleep rebound. (A) Diagram depicting Cre-dependent recombination of AAV-DIO-hM3Dq-mCherry in Vglut2-ires-Cre:APPSwe/PS1δE9 mice. (B) Labeling of mCherry-tagged hM3Dq using an anti-DsRed antibody (counterstain cresyl violet, scale bar 500 μm). (C) Timeline of hM3Dq-mediated manipulation of the SuM. (D) EEG data showing significantly increased wakefulness over 9 hours following CNO injection compared to the non-treated day (n=8: 4F, 4M, two-way repeated measures ANOVA, interaction: p<0.0001, Bonferroni post-hoc). (E) NaCl injection in AAV-hM3Dq mice showed no effect on % wakefulness (n=6: 1F, 5M). (F-H) Analysis of % wakefulness (F), % NREM sleep (G) and % REM sleep (H) between 06:00–09:00 (before CNO), 09:00–18:00 (after injection of CNO), and 18:00–06:00 (following night) showed significantly increased wakefulness and decreased sleep following CNO injection (red) compared to the non-treated day (black) but no differences prior to CNO injection. Analysis of the dark period (18:00–06:00) showed similar levels of % wakefulness and sleep in both groups demonstrating a lack of NREM or REM sleep rebound following sustained wakefulness over a period of 9 hrs (two-way repeated measures ANOVA, interaction: p<0.0001, Bonferroni post-hoc). All data represent mean ± SEM. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

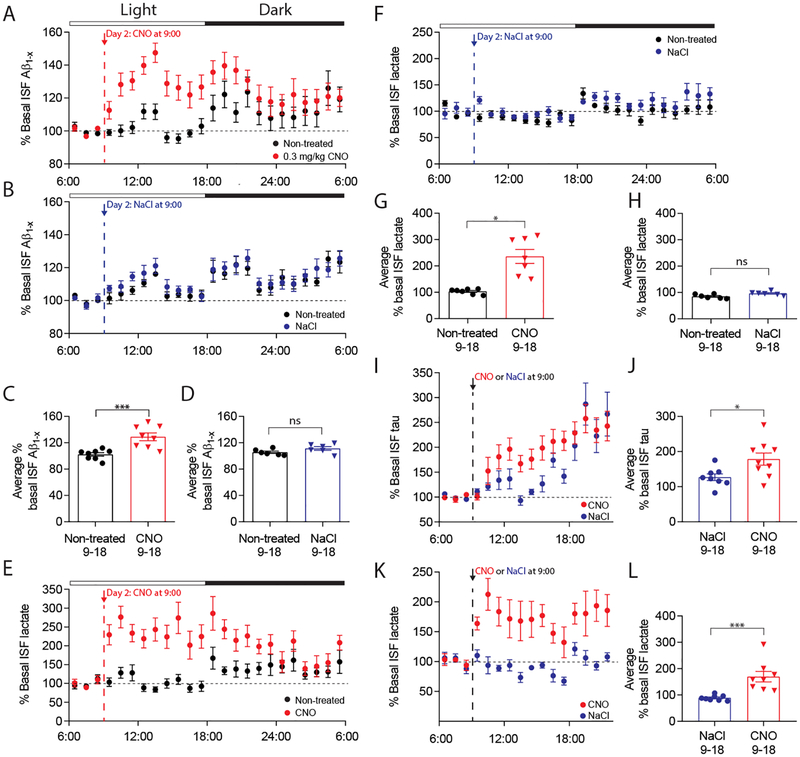

We next asked how ISF Aβ was influenced by the sleep-wake cycle and chemogenetic induction of wakefulness. As we have seen previously, ISF Aβ was higher during the dark phase vs. the light phase in the 24 hours prior to treatment in both groups (Fig. 4A, B, table S1, S5). Following treatment of Cre-expressing APPswe/PS1δE9 mice with CNO there was a strong and significant increase of both ISF Aβ, which peaked at 30% over baseline (Fig. 4A, C, table S1, S5), and ISF lactate (Fig 4E, G). In mice treated with vehicle, there were no changes in ISF Aβ (Fig. 4B, D, table S1, S5) or lactate (Fig. 4F, H). In addition, there was no effect of CNO on Aβ in non-AAV injected APPswe/PS1δE9 mice (fig. S7). To assess ISF tau using the chemogenetic approach, Vglut2-ires-Cre mice were injected with AAV-hM3Dq at 2.5–3 months of age. Before assessing the mice by microdialysis, we used activity tracking to determine that CNO increased wakefulness (fig. S8). 5–7 weeks post-injection, mice underwent in vivo microdialysis and ISF tau was assessed when treated with either CNO or NaCl. CNO treatment significantly increased ISF tau by ~40% and lactate by ~90% (Fig. 4I–L, table S1, S6) compared to NaCl-treated mice.

Fig. 4.

Chemogenetic activation of glutamatergic supramammillary neurons increases hippocampal ISF Aβ, tau, and lactate levels. (A) ISF Aβ levels normalized to baseline (06:00–09:00) during a 24-hour untreated period (black) and 24-hour period with CNO (red, n=8: 4F, 4M) or (B) NaCl injection (blue, n=6: 1F, 5M). (C) Average ISF Aβ was significantly increased after injection of CNO (09:00–18:00) compared to the untreated day (n=8, paired t-test). (D) NaCl control injection did not alter average ISF Aβ (n=6). (E) Normalized ISF lactate levels before and after CNO (n=7: 4F, 3M) and (F) NaCl injection (n=6). (G) Average ISF lactate was significantly increased after CNO injection (09:00–18:00) compared to the untreated day (n=7, Wilcoxon signed rank). (H) Average ISF lactate following control NaCl injection (09:00–18:00) was unchanged. (I) ISF tau levels normalized to baseline (06:00–09:00) in CNO-treated mice (n=9: 3F, 6M) and NaCl-injected controls (n=8: 4F, 4M). (J) ISF tau post CNO treatment (09:00–18:00) was significantly increased compared to NaCl controls (n=8–9, unpaired t-test). (K) Normalized ISF lactate levels of CNO (n=8: 3F, 5M) and NaCl-treated mice (n=8: 4F, 4M). (L) Average ISF lactate post CNO treatment (09:00–18:00) was increased compared to NaCl controls (n=8, Mann-Whitney). All data represent mean ± SEM. *p<0.05, ***p<0.001.

We have shown that ISF tau is regulated by the sleep-wake cycle and that both ISF tau in mice and CSF tau in humans are strongly increased by sleep deprivation. ISF tau was increased with physical and chemogenetic induction of wakefulness. Interestingly, the half-life of tau in the brain is long (~10 days in mice and over 20 days in humans) (22, 23). However, once tau reaches the extracellular space in the ISF or CSF, its half-life is very short (1–2 hours) (24). Thus, changes in the sleep-wake cycle can result in rapid changes in ISF and CSF tau. Since TTX blocks the increase in tau due to sleep deprivation, it seems likely that the mechanism by which tau increases with wakefulness and sleep deprivation is linked with elevated neuronal metabolism/synaptic strength causing enhanced tau release. While the exact mechanism of tau release is unclear, the changes observed here represent free, non-vesicle or exosome associated tau. It is also possible that decreased ISF tau clearance during wakefulness could contribute to the change observed. The fact that in human CSF we see changes in tau and synuclein but not all proteins following sleep deprivation argues that the changes are more likely due to increased release of certain proteins rather than changes in global ISF clearance.

We and others have found that the sleep-wake cycle influences Aβ levels both acutely and chronically, which can influence the pathogenesis of AD (15, 25). While there is a lot of evidence that Aβ aggregation initiates AD-pathogenesis including driving neocortical tau aggregation/spreading, tau accumulation appears to drive neurodegeneration. The acute increases in monomeric ISF tau by wakefulness and sleep deprivation may play a normal role in cell signaling whereas increased release of pathological species may play a role in seeding, spreading, and neurodegeneration. The observation that increased wakefulness can increase ISF and CSF tau, tau spreading, and increase tau aggregation over longer periods of time (26) in mice provides evidence for its key role in regulating tau pathology. Thus, optimization of the sleep-wake cycle should be an important treatment target to test in the prevention of AD and other tauopathies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We wish to thank Floy Stewart with her assistance with microdialysis, Cliff Saper and Quan Hue Ha for assistance learning SuM DREADD, Ronald DeMattos at Eli Lilly for providing m266 and 3D6 antibodies for ELISA, and Peter Davies for providing the MC1 antibody.

Funding: Supported by a grant from the BrightFocus Foundation (A2017114F, SKF); funding from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (3625/1–1, SKF); NIH F32 NS089381 (JKH); NIH K08NS105929 (NPP), NIH R01NS073613 (PMH), R01NS092652 (PMF); NIH P01NS074969 (DMH); the JPB Foundation (DMH); the Tau Consortium (DMH); UL1 TR000448 and KL2 TR000450 (BPL); R03 AG047999 (BPL); K76 AG054863 (BPL); P50 AG05681 (BPL); P01 AG26276 (BPL); McDonnell Center for Systems Neuroscience at Washington University School of Medicine (BPL).

Footnotes

Competing interests: D.M.H. co-founded and is on the scientific advisory board of C2N Diagnostics. D.M.H. is on the scientific advisory board of Denali, Genentech, and Proclara. D.M.H. consults for AbbVie. None of the authors report competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data is available in the main text or the supplementary materials.

References and Notes

- 1.Spillantini MG, Goedert M, Tau pathology and neurodegeneration. Lancet neurology 12, 609–622 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bejanin A et al. , Tau pathology and neurodegeneration contribute to cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 140, 3286–3300 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clavaguera F et al. , Transmission and spreading of tauopathy in transgenic mouse brain. Nature cell biology 11, 909–913 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frost B, Diamond MI, Prion-like mechanisms in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Rev Neurosci 11, 155–159 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iba M et al. , Synthetic tau fibrils mediate transmission of neurofibrillary tangles in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s-like tauopathy. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 33, 1024–1037 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Calignon A et al. , Propagation of tau pathology in a model of early Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 73, 685–697 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu L et al. , Trans-synaptic spread of tau pathology in vivo. PLoS ONE 7, e31302 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pooler AM, Phillips EC, Lau DH, Noble W, Hanger DP, Physiological release of endogenous tau is stimulated by neuronal activity. EMBO reports 14, 389–394 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamada K et al. , Neuronal activity regulates extracellular tau in vivo. The Journal of experimental medicine 211, 387–393 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu JW et al. , Neuronal activity enhances tau propagation and tau pathology in vivo. Nat Neurosci 19, 1085–1092 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vyazovskiy VV, Cirelli C, Pfister-Genskow M, Faraguna U, Tononi G, Molecular and electrophysiological evidence for net synaptic potentiation in wake and depression in sleep. Nat Neurosci 11, 200–208 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bero AW et al. , Neuronal activity regulates the regional vulnerability to amyloid-beta deposition. Nat Neurosci 14, 750–756 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uehara T, Sumiyoshi T, Itoh H, Kurata K, Lactate production and neurotransmitters; evidence from microdialysis studies. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 90, 273–281 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roh JH et al. , Disruption of the Sleep-Wake Cycle and Diurnal Fluctuation of beta-Amyloid in Mice with Alzheimer’s Disease Pathology. Sci Transl Med 4, 150ra122 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang JE et al. , Amyloid-beta dynamics are regulated by orexin and the sleep-wake cycle. Science 326, 1005–1007 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lucey BP et al. , Effect of sleep on overnight cerebrospinal fluid amyloid beta kinetics. Ann Neurol 83, 197–204 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamada K, Iwatsubo T, Extracellular α-synuclein levels are regulated by neuronal activity. Mol Neurodegener 13, 9 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yanamandra K et al. , Anti-Tau Antibodies that Block Tau Aggregate Seeding In Vitro Markedly Decrease Pathology and Improve Cognition In Vivo. Neuron 80, 402–414 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Busche MA et al. , Tau impairs neural circuits, dominating amyloid-β effects, in Alzheimer models in vivo. Nat Neurosci 22, 57–64 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pedersen NP et al. , Supramammillary glutamate neurons are a key node of the arousal system. Nat Commun 8, 1405 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jankowsky JL et al. , Mutant presenilins specifically elevate the levels of the 42 residue beta-amyloid peptide in vivo: evidence for augmentation of a 42-specific gamma secretase. Hum Mol Genet 13, 159–170 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamada K et al. , Analysis of in vivo turnover of tau in a mouse model of tauopathy. Molecular neurodegeneration 10, 55 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sato C et al. , Tau Kinetics in Neurons and the Human Central Nervous System. Neuron 98, 861–864 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yanamandra K et al. , Anti-tau antibody administration increases plasma tau in transgenic mice and patients with tauopathy. Sci Transl Med 9, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xie L et al. , Sleep drives metabolite clearance from the adult brain. Science 342, 373–377 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu Y et al. , Chronic Sleep Disruption Advances the Temporal Progression of Tauopathy in P301S Mutant Mice. J Neurosci 38, 10255–10270 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamada K et al. , In Vivo Microdialysis Reveals Age-Dependent Decrease of Brain Interstitial Fluid Tau Levels in P301S Human Tau Transgenic Mice. Journal of Neuroscience. 31, 13110–13117 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cirrito JR et al. , In vivo assessment of brain interstitial fluid with microdialysis reveals plaque-associated changes in amyloid-beta metabolism and half-life. Journal of Neuroscience. 23, 8844–8853 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Macauley SL et al. , Hyperglycemia modulates extracellular amyloid-β concentrations and neuronal activity in vivo. J. Clin. Invest 125, 2463–2467 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patterson BW et al. , Age and amyloid effects on human central nervous system amyloid-beta kinetics. Ann Neurol. 78, 439–453 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Machado RB, Hipólide DC, Benedito-Silva AA, Tufik S, Sleep deprivation induced by modified multiple platform technique: quantification of sleep loss and recovery. Brain Res. 1004, 45–51 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.