Abstract

Adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia (ALSP) is a rare white matter degenerative disease characterized by both axonal and glial injury due to a defect in the CSF1R gene. In this report, we describe ALSP in a previously healthy 40-year-old woman presenting with insidiously progressive confusion, memory loss, and loss of social inhibitions. Characteristic magnetic resonance imaging findings for ALSP elucidated the diagnosis, including chronic foci of diffusion restriction in a non-vascular distribution, lack of temporal/infratentorial involvement, cortical sparing, and lack of enhancement. CSF1R genetic testing further confirmed the diagnosis and the patient underwent supportive medical management for symptom control. ALSP can pose a unique diagnostic challenge given its particular adult-onset presentation, but early recognition is key given the poor prognosis and the potential for family genetic testing.

Keywords: Adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia, CSF1R gene, leukodystrophy, leukoencephalopathy, neurodegenerative disease

Introduction

Until recently, adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia (ALSP) was identified as two different disease entities, namely: hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids (HDLS) and familial pigmentary orthochromatic leukodystrophy (POLD).1 However, with the discovery that both diseases are caused by the same mutation involving a receptor regulating microglia function in the CSF1R gene, both entities are now considered to be on the same spectrum of disease termed ALSP.2 Although ALSP can occur sporadically, its inheritance pattern is thought to be autosomal dominant with incomplete penetrance.3 ALSP can have variable manifestations including behavioral and mood changes, motor dysfunction, dementia, and seizures.4 With such a wide array of symptoms, patients with ALSP are often misdiagnosed and, therefore, the true prevalence is difficult to ascertain and is likely to be underestimated.4 In this case report, we highlight a case of ALSP with characteristic clinical and radiological findings, which was subsequently confirmed by CSF1R genetic testing.

Case report

A 40-year-old woman with an unremarkable past medical history presented with a headache, altered mental status, and perseveration of speech. The patient’s family reported that she had been behaving strangely at home for the past month and was seen opening and closing cabinets repeatedly, turning faucets and light switches on and off, laughing inappropriately, and getting “stuck on words.” Other than the mental status changes, as well as speech and memory deficits, the patient’s physical examination was otherwise unremarkable and without focal deficits.

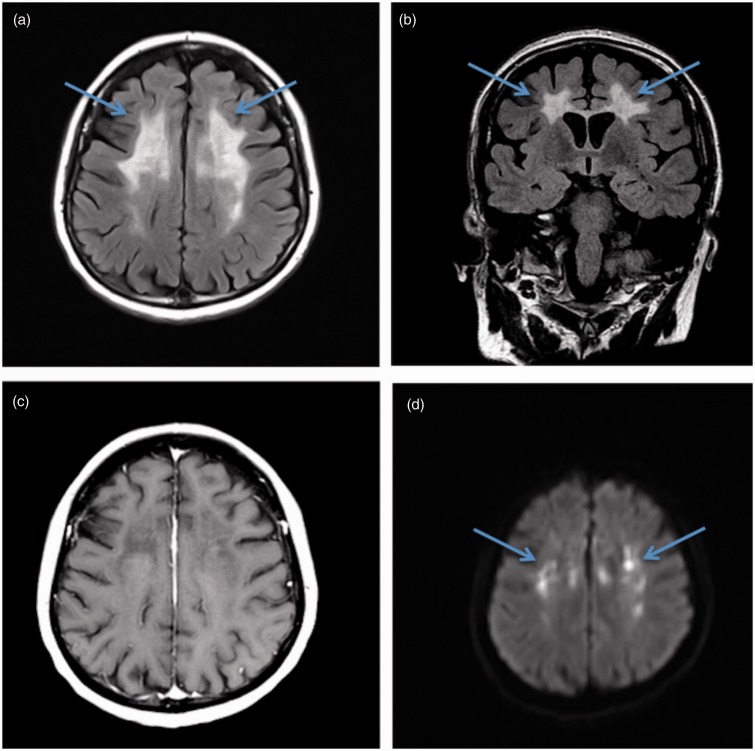

Laboratory workup and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis were within normal limits. Autoimmune and infectious serologies including Sjogren, lupus, lyme, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), human T-cell lymphotropic virus (HTLV), and hepatitis were all negative. Computed tomography (CT) imaging demonstrated non-specific white matter abnormalities without evidence of intracranial hemorrhage, mass effect, or large territorial infarcts. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated extensive confluent subcortical white matter T2 hyperintense signal abnormalities in a frontoparietal distribution including the corpus callosum, with sparing of the temporal lobes and brainstem. Corresponding scattered foci of diffusion restriction without contrast enhancement were also noted in a non-vascular distribution (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Brain magnetic resonance imaging demonstrating characteristic findings of adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia (ALSP). (a) Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) image demonstrates subcortical frontoparietal hyperintensities (arrows), with sparing of the temporal lobes and brainstem. (b) Characteristic lack of enhancement on postcontrast T1-weighted axial image (c) and corresponding chronic foci of diffusion restriction (arrows) on diffusion-weighted images (DWIs) (d). The atypical distribution of the non-enhancing white matter disease and persistent chronic ischemic/diffusion restriction changes are unique findings that are highly suspicious for ALSP.

The initial working diagnosis was bilateral strokes, likely due to a hypercoagulable state and the patient was started on anticoagulation with warfarin and aspirin. The patient’s symptoms persisted and further family history was discovered to include two paternal aunts who died in their forties due to “stroke and dementia” and a cousin who died in his forties due to “Parkinson’s” overseas. Given the family history of neurological disease, unusual presentation with worsening of the patient’s mental status, and persistence of diffusion restriction on follow-up MRI which is not typical for an ischemic event, additional diagnoses were considered. These included cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL), Susac disease, demyelinating disease, and rare adult-onset leukodystrophies.

Further workup included brain biopsy demonstrating white matter reactive gliosis, myelin loss, and prominent neuroaxonal spheroids, suggestive of a leukodystrophy with neuroaxonal spheroids. Genetic testing revealed a CSF1R mutation (c.2330G > A; p.Arg777Gln) confirming the diagnosis of ALSP. The patient is currently undergoing supportive medical management for symptom control, and has been transferred to a skilled nursing facility due to worsening neurological status and poor prognosis. The patient’s family is being evaluated for ALSP with potential testing.

Discussion

ALSP is a rare leukodystrophy with a unique adult-onset onset and frontal lobe syndrome presentation. The symptoms present early in the disease course with alarming deficits in executive function, memory and speech, motor skills, and personality and social interaction. As the disease progresses, patients often develop seizures, and then ultimately become bedbound with spasticity and rigidity.5 The mean age of onset is 43 years with an earlier presentation in women on average (40 years) compared to men (47 years).6 The disease course has been reported to be as rapid as two years, which is catastrophic given the typical early adulthood onset.5 While ALSP is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner, it demonstrates incomplete penetration skipping generations, and de novo mutations also occur, often making it difficult to diagnose or predict its manifestation.

The differential diagnosis for ALSP is broad. Although alarming and unusual, the presentation is nonspecific and is a great mimicker of neurodegenerative, metabolic, autoimmune, and infectious disorders. Histologically-confirmed cases of ALSP at autopsy studies have been shown to have been clinically incorrectly diagnosed or suspected of having primary progressive multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer's disease, CADASIL, atypical Parkinson's disease, frontotemporal dementia, and vascular dementia.1 Additional considerations for white matter disease in early adulthood include HIV, sub-acute sclerosing panencephalitis, Bechet’s disease, and lupus encephalitis. While imaging is not always diagnostic, it can narrow the differential, particularly when there are unique findings such as chronic foci of diffusion restriction in a non-vascular distribution, temporal/infratentorial and cortical sparing, and lack of enhancement.

The most commonly reported MRI finding of ALSP is bilateral patchy or confluent T2 hyperintensities with frontal lobe predominance and associated cerebral atrophy.7 It is now believed that these white matter lesions start out patchy and become confluent as the disease progresses.8 The white matter abnormalities typically spare the cortex and are usually asymmetric, particularly in the early stages of the disease.5 Associated chronic small foci of diffusion restriction and lack of contrast enhancement are unique findings, which are helpful when present. On CT imaging, white matter calcifications have been reported in some patients with ALSP, revealing a characteristic pattern of “stepping stone appearance” in the pericallosal region.6

Prompt diagnosis of ALSP is of great importance to spare the patient from a prolonged work-up and to optimize their quality of life given the poor prognosis often with a rapid course. The mainstay of treatment is supportive management with a focus on symptom control and maintaining nutritional requirements. Antiepileptics and antidepressants are recommended for patients presenting with seizures and depression symptoms, respectively, while dopaminergic therapies and multiple sclerosis agents do not appear to be beneficial to ALSP patients.5 While no ALSP medications are currently available, current research focuses on the role of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation as a future therapy.8 Lastly, genetic counseling can be considered for patients and family members.

Conclusion

We discuss a patient with ALSP who presented with adult-onset progressive altered mental status, memory loss, and loss of social inhibitions. The diagnosis was established by characteristic MRI findings and confirmed by brain-biopsy and genetic testing. Characteristic MRI findings for ALSP, which are helpful when present, include chronic foci of diffusion restriction in a non-vascular distribution, temporal/infratentorial and cortical sparing, and lack of enhancement. While ALSP is a rare disease and the diagnosis is often difficult to elucidate, early recognition is key given the poor prognosis, rapid course, and genetic testing implications for family members.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Adams SJ, Kirk A, Auer RN. Adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia (ALSP): Integrating the literature on hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids (HDLS) and pigmentary orthochromatic leukodystrophy (POLD). J Clin Neurosci 2018; 48: 42–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nicholson AM, Baker MC, Finch NA, et al. CSF1R mutations link POLD and HDLS as a single disease entity. Neurology 2013; 80: 1033–1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keegan BM, Giannini C, Parisi JE, et al. Sporadic adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with neuroaxonal spheroids mimicking cerebral MS. Neurology 2008; 70: 1128–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NIH US National Library of Medicine, Genetics Home Reference. Adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia, www.ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/adult-onset-leukoencephalopathy-with-axonal-spheroids-and-pigmented-glia#inheritance (2018, accessed 1 August 2018).

- 5.Sundal C and Wszolek ZK. CSF1R-related adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia. GeneReviews, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK100239/ (2017, accessed 1 August 2018).

- 6.Konno T, Yoshida K, Mizuno T, et al. Clinical and genetic characterization of adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia associated with CSF1R mutation. Eur J Neurol 2017; 24: 37–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sundal C, Lash J, Aasly J, et al. Hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids (HDLS): A misdiagnosed disease entity. J Clin Neurosci 2012; 314: 130–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eichler FS, Li J, Guo Y, et al. CSF1R mosaicism in a family with hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids. Brain 2016; 139: 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]