Abstract

Aims

To examine the availability of frailty concept with objective criteria for risk stratification in patients with congestive heart failure (CHF).

Methods and results

Study design was secondary analysis of our CHF cohort. We selected 181 patients who completed clinical assessments and were successfully followed 2‐year post discharge. To set frailty criteria, grip strength <26 kg in men and <17 kg in women (weakness) and performance measure for activities of daily living‐8 ≧21 points (exhaustion) were defined for predicting 6 min walking distance <300 m (slowness) by the receiver‐operating characteristics. During 2 years of follow up, subjects who met all the criteria had a 4 times greater risk of cardiac event compared with those with no frailty criteria.

Conclusion

The findings of present study suggest that frailty criteria may serve as a new clinical marker for management of patients with CHF.

Keywords: Congestive heart failure, frailty, elderly, 6 minutes‐walk distance, grip strength, performance measure for activities of daily living‐8

Frailty is essential to all‐cause mortality and is now understood as a medical syndrome in the elderly.1 Loss of muscle mass or body weight because of undernutrition and/or ageing leads to muscle weakness, walking slowness, and, in turn, physical inactivity known as frailty components. Despite of different aetiology, weight loss, a main clinical marker of frailty, is concurrently a powerful prognostic marker known as cardiac cachexia in advanced congestive heart failure (CHF). Although McNallan SM et al. recently reported that frailty served as a prognostic factor in patients with CHF, they set most of the frailty criteria with questionnaires.2 The criteria with objective measures including grip strength or walking speed would help physicians to identify the patients who fall into frailty state exactly. Added to this, frailty criteria in patients with particular disease should be considered desirable when it predicts disease‐specific outcomes. We therefore aimed to examine the availability of frailty concept with objective criteria for risk stratification in patients with CHF.

From our own series of patients with CHF (PTMaTCH cohort3), we selected 181 patients (age: 68.1 ± 9.7 years, 125 male patients, 47.8% in patients with coronary, 27.0% in cardiomyopathy, body mass index: 22.6 ± 3.2 kg/m2, New York Heart Association classification at admission (n,II/III/IV): 43/76/62, left ventricular ejection fraction: 39.2 ± 16.1%) who completed clinical assessments and were successfully followed up for 2 years post discharge. Six minutes walking distance (6MD), grip strength at hospital discharge and performance measure for activity of daily living‐8 (PMADL‐8), a questionnaire to assess functional limitation in patients with CHF,4 at 1‐month post discharge were adopted to slowness, weakness, and exhaustion in frailty criteria.

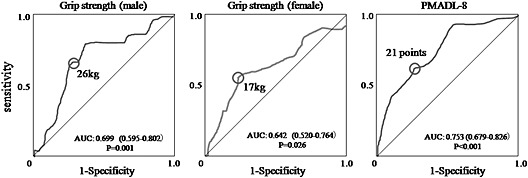

First, we decided 6MD cutoff level for frailty as <300 m because this value is almost equal as 10 m walking speed of 0.8 m/s of frailty criteria.5 Then, we analysed cutoff values of grip strength and PMADL‐8 for predicting 6MD <300 m by the receiver‐operating characteristics. Finally, we evaluated the impact of frailty criteria on long‐term cardiac events or heart failure re‐hospitalization or any cause hospitalization. Based on receiver‐operating characteristics analysis, we selected 6MD <300 m, PMADL‐8 ≥ 21 points (ranged from 8 to 32 points, the higher points mean greater functional limitation), grip strength <26 kg in men and <17 kg in women as criteria for CHF frailty (Figure 1). Then, we divided participants into four groups based on the number of CHF frailty criteria.

Figure 1.

Receiver‐operating characteristics analysis of grip strength and performance measure for activities of daily living‐8 (PMADL‐8) for predicting 6 min walking distance less than 300 m. We identified a cut‐off value of grip strength 26 kg in men with a sensitivity of 64.5% and a specificity of 75.5%, 17 kg in women with a sensitivity of 56.8% and a specificity of 76.6%, and PMADL‐8 score of 21 points with a sensitivity of 63.7% and a specificity of 72.2%.

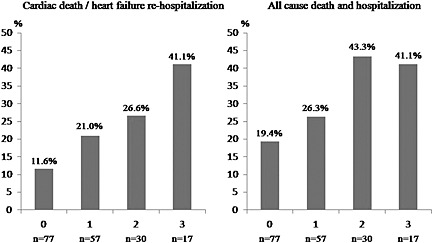

During 2‐year post discharge, 36 out of 181 patients manifested cardiac death or heart failure re‐hospitalization and additional 14 patients had hospitalization by reasons other than cardiac reason. When compared with no criteria group, the patients who met all of three criteria had a 4 times greater cardiac event rate; however, this rate fell to one half when analysed for all cause events because of higher incidence rate in no criteria group (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Cumulative event rates for cardiac death/heart failure re‐hospitalization and all‐cause death and hospitalization.

In this report, we identified that frailty concept would be available for risk stratification in patients with CHF. Each of risk factors, low 6MD,6 high PMADL‐8 points4, and low grip strength,7 has been reported to predict adverse event in patients with CHF. Added to this, the findings of our study showed that by adopting frailty concept to risk factor selection, the combined effect of these factors offset the predictability of each factor, particularly in predicting cardiac events.

There are many similarities between symptoms in patients with CHF and in frail subjects. Two major symptoms of fatigability and shortness of breath in patients with CHF are the same symptoms as those in physical frailty subjects even though the underling mechanism is different. Although the frailty frequently exists concurrently with disease and disability, frailty concept basically arose in distinction from these characteristics.5 Therefore, the availability of frailty concept should be examined in disease population with disease specific outcomes.

The findings of this study also suggest that CHF frailty criteria may enable to stratify the patients for determining the way of rehabilitation intervention. Patients without frailty should be treated with aerobic exercise and resistance training as usual. In contrast, patients with frailty may be treated with both of sufficient nutrition intervention and resistance training to enhance anabolism. The treatment could be shifted to ordinary intervention when frailty state is improved. However, if frail state is not improved, the other strategies should be taken into account to manage their disease state and functional condition. Thus, frailty criteria could be a tool for clinical management of CHF.

We must consider several limitations. First, because our study was secondary analysis, some confounding factors may exist. Second, we did not assess the change of weight and physical activity, which are usually included in the criteria of frailty phenotype. Further prospective cohort with greater number of cases will need to develop the items and their cutoff values in CHF frailty criteria and to examine its clinical validation. Third, we did not take into account the aetiology. It is possible that the effects of frailty on adverse outcomes are different by aetiology, preserved or reduced left ventricular ejection fraction or aortic valvular disease. It should be considered in future studies.

In conclusion, this report indicates that simple and easy to assess criteria of frailty may serve as a marker for adverse outcomes in patients with CHF. Developing the CHF frailty criteria with a large multicenter prospective cohort study may be a demand of aged society.

Ethical Statement

The study protocol of PTMaTCH was approved by the Ethics Review Boards of the Nagoya University School of Medicine (approval no. 493) and each participating medical centre. Written informed consent was obtained from each of the patients before study entry.

Acknowledgement

PTMaTCH was supported by a Grant‐in‐Aid for Scientific Research (B) to the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (grant: 19399190).

Yamada, S. , Kamiya, K. , and Kono, Y. (2015) Frailty may be a risk marker for adverse outcome in patients with congestive heart failure. ESC Heart Failure, 2: 168–170. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12052.

References

- 1. Morley JE, Vellas B, van Kan GA, Anker SD, Bauer JM, Bernabei R, Cesari M, Chumlea WC, Doehner W, Evans J, Fried LP, Guralnik JM, Katz PR, Malmstrom TK, McCarter RJ, Robledo LMG, Rockwood K, Haehling SH, Vandewoude SF, Walston J. Frailty consensus: a call to action. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2013; 14:392–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McNallan SM, Chamberlain AM, Gerber Y, Singh M, Kane RL, Weston SA, Dunlay SM, Jiang R, Roger VI. Measuring frailty in heart failure: a community perspective. Am Heart J 2013;166:768–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shimizu Y, Yamada S, Miyake F, Izumi T. The effects of depression on the course of functional limitations in patients with chronic heart failure. J Card Fail 2011;17:503–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yamada S, Shimizu Y, Suzuki M, Izumi T. Functional limitations predict the risk of rehospitalization among patients with chronic heart failure. Circ J 2012;76:1654–1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, Seeman T, Tracy R, Kop WJ, Burke G, McBurnie MA. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001;56:M146–M156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Roul G, Germain P, Bareiss P. Does the 6‐minute walk test predict the prognosis in patients with NYHA class II or III chronic heart failure? Am Heart J 1998;136:449–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Izawa KP, Watanabe S, Osada N, Kasahara Y, Yokoyama H, Hiraki K, Morio Y, Yoshioka S, Oka K, Omiya K. Handgrip strength as a predictor of prognosis in Japanese patients with congestive heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2009;16:21–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]