Abstract

Incomplete understanding of the mechanisms responsible for induction of hibernation prevent translation of natural hibernation to its artificial counterpart. To facilitate this translation, a model was developed that identifies the necessary physiological changes for induction of artificial hibernation. This model encompasses six essential components: metabolism (anabolism and catabolism), body temperature, thermoneutral zone, substrate, ambient temperature, and hibernation-inducing agents. The individual components are interrelated and collectively govern the induction and sustenance of a hypometabolic state. To illustrate the potential validity of this model, various pharmacological agents (hibernation induction trigger, delta-opioid, hydrogen sulfide, 5’-adenosine monophosphate, thyronamine, 2-deoxyglucose, magnesium) are described in terms of their influence on specific components of the model and corollary effects on metabolism.

Relevance for patients: The ultimate purpose of this model is to help expand the paradigm regarding the mechanisms of hibernation from a physiological perspective and to assist in translating this natural phenomenon to the clinical setting.

Keywords: anapyrexia, hypometabolic agents, hypometabolism, natural hibernation, torpor, thermoneutral zone, hypoxia, body temperature, thermal convection, Arrhenius law

Contents

- 1.

-

2.

A model for hypometabolic induction (80)

-

2.1.

Control of metabolism through temperature and substrate availability (80)

-

2.2.

Thermoregulation following a shift in the thermoneutral zone (80)

-

2.3.

Hypoxia-induced hypometabolism: aligning anabolism with catabolism (81)

-

2.4.

The effect of hypoxia-induced anapyrexia on thermoregulatory effectors (83)

-

2.5.

Pharmacological agents and induction of artificial hypometabolism (84)

- 2.5.1.

- 2.5.2.

- 2.5.3.

- 2.5.4.

- 2.5.5.

- 2.6.

-

2.7.

Hypothermia and hypometabolism research and clinical implementation: important considerations (88)

-

2.1.

- 3.

1. Introduction

Metabolic homeostasis is key to physical function, justifying its meticulous regulation and powerful governing mechanisms in every living cell. The ability to artificially and reversibly reduce metabolism could provide many advantages for medicine, sports, and aviation. However, despite a growing understanding of our ability to regulate the mechanisms that govern metabolism at the cellular level, translation of metabolic control in cells to a whole organism has remained beyond our reach.

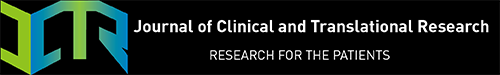

In nature, reversible states of hypometabolism are a common trait. Members of eight species, including a variety of rodents, carnivores (bears), and primates (lemurs) are known to exhibit a type of hypometabolism [1]. Although biological vernacular varies between many different types of hypome- tabolism (Figure 1), two types can generally be distinguished within animals that have an endogenous thermoregulatory system: a deep and a shallow type of hypometabolism. The difference lies in the depth of the drop in body temperature (Tb) and the duration. Shallow hypometabolism represents a temporary type, as exhibited during torpor by e.g., the house mouse, whereas deep hypometabolism is a more sustainable type, as is found in e.g., the hibernating ground squirrel [1, 2].

Figure 1. Classification of the different types of hyper- and hypometabolism and the official biological vernacular. Endogenous thermoregulation occurs through the modulation of the thermoneutral zone (Ztn) and thermal effectors, whereas exogenous thermoregulation is dependent on the ambient temperature (Ta) and exogenous triggers but not the Ztn.

The mechanism(s) responsible for the induction of hypometabolism remain(s) controversial [1]. Unfavorable environmental circumstances appear to be a common denominator in hibernating animals, including seasonal cooling, light deprivation, and prolonged starvation. However, the use of such external triggers to induce artificial hibernation in humans has proven to be of no avail. Irrespective of the external cues, an internal physiological signal, or perhaps a concerted cascade of signals, must initiate, propagate, govern, and sustain hypometabolic signaling in vivo. In an attempt to find such a signal, much research has focused on (bio)chemical signaling during hibernation and its induction, leading to the identification of several hypometabolic agents [3-7]. However, despite their discovery and extensive research in various animal models, none of the identified agents appear to induce a hypometabolic state ubiquitously across species, as a result of which not a single hypometabolic agent has made it yet to (pre)clinical application. Currently, the only metabolic control that is clinically employed is forced hypothermia-induced hypometabolism, although this type of hypometabolism fails to achieve the depth found in natural hibernators and comes with challenging limitations.

In an attempt to expand on current insights into hypometabolism, this review addresses the conditions necessary for the induction of hypometabolism and the possible initial (biochemical) triggers. Accordingly, a theorem on the induction of hypometabolism is presented, whereby the relationship between key physiological and environmental factors is provided as a framework to explain the physiological cascade that leads to a sustainable and reversible state of hypometabolism in mammals. Readers should note that the focus of this paper is on mainly the physiological and biochemical conditions required for the induction of hypometabolism. Although neurological signal relay is key to convey, propagate, and sustain a state of hypothermia and hypometabolism, the responsible neurological pathways have only been superficially addressed. These pathways will be elaborated in more detail in a subsequent, separate review.

2. A model for hypometabolic induction

2.1. Control of metabolism through temperature and substrate availability

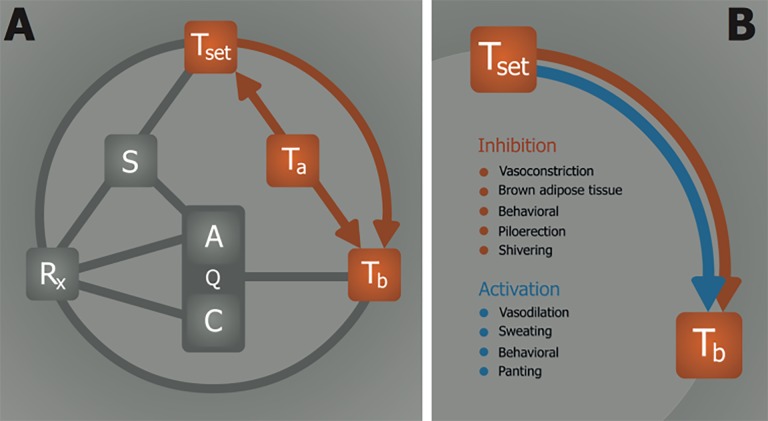

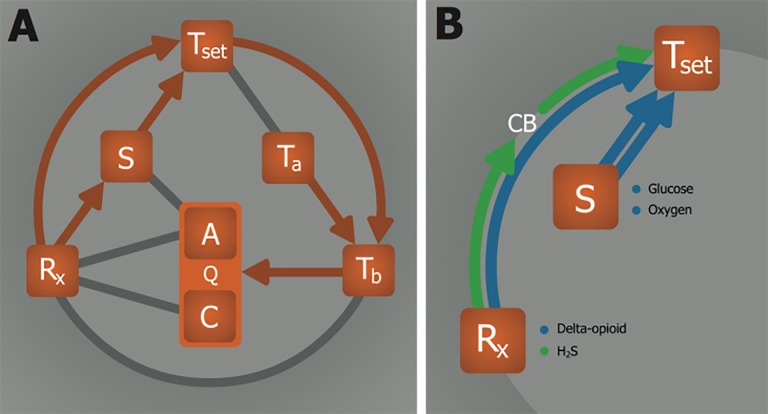

A pivotal step in the induction of artificial hypometabolism is gaining control over the most important factors that regulate metabolism (Q), namely the availability of substrate (S, i.e., oxygen and glucose) and the rate of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production (anabolism, A) and consumption (catabolism, C), which are both influenced by the core body temperature (Tb). Hence, a direct relationship exists between Tb and Q (Figure 2) as well as between S and A(Figure 2). The relationship between Tb and Q essentially abides by Arrhenius’ law, which states that the chemical (i.e., enzymatic) reaction rate, Q, is reduced as a result of lowering of temperature (Equation 1).

Figure 2. Substrate and temperature effects on metabolism. The S—Q relationship relies on substrate (S) availability to support anabolism (A). The Tb—Q relationship is dictated by the Arrhenius equation (Equation 1, where k is equal to Q in this model), which governs the relation between body temperature (Tb) and chemical reaction speed (Q). Catabolism (C) is directly affected by Tb, but not by S.

Equation 1.

Arrhenius equation:

Although the magnitude of Q varies among enzymes, all have in common that Q is temperature-dependent and therefore relies on Tb. The directly proportional effect of Tb on Q is in turn affected by the ambient temperature (Ta), which impacts Tb and hence Q through heat exchange (Figure 2). The (Ta—)Tb— Q relationship is widely exploited in the clinical setting, as exemplified by the contrived reduction in patients’ Tb through direct or indirect cooling (e.g., reduction in Ta by means of breathing cold air, cutaneous cooling, organ perfusion with a cold solution, or intravascular cooling) as a protective strategy in surgery [8, 9], neurology [10], cardiology [11], trauma [12], and intensive care [13]. The protective effects of mild to moderate hypothermia (Tb reduction to ~35-32 °C) have been ascribed to lower radical production rates, ameliorated mitochondrial injury/dysfunction, reduced ion pump dysfunction, and cell membrane leakage, amongst others [14]. The majority of these factors is directly related to the rate at which chemical reactions proceed, whereby cytoprotection is conferred by a Tb-mediated reduction in Q in accordance with the Arrhenius equation (Equation 1).

The generally protective effects of hypothermia notwithstanding, the advantage of clinically forced hypothermia-induced hypometabolism is questionable in some instances. At mild hypothermia (~35 °C), serum concentrations of norepinephrine start to rise in response to hypothermic stress, coagulopathy starts to develop, susceptibility to infections increases, and mortality rates are negatively affected [15-17]. When the Tb is lowered further to ~30 °C, severe hypothermia-related complications may occur, including ventilatory and cardiac arrest [14,18]. An even more profound reduction in Tb would require mechanical ventilation with extensive monitoring and would considerably increase procedural risks. Accordingly, in the last five decades, the limit of ~30 °C has not been adjusted downward in the clinical setting as much as it has been refined, despite of successful animal experiments with much deeper hypothermia [19-22].

The detrimental effects associated with forced deep hypothermia reflect the limits of the practical implementation of the (Ta—)Tb—Q relationship. It is evident that the (Ta—)Tb—Q relationship must be differentially regulated in natural hibernators compared to humans. In natural hibernators the Tb—Q effects may be integratively mediated by endogenous signaling, such as by the release of biochemical agents or by hypoxia (both addressed in detail below). Humans essentially lack such endogenous pathways and do not exhibit hypothermia-related benefits from exogenously administered pharmaceuticals or hypoxia, as a result of which Q cannot be actively adjusted downward by other pathways than through the Tb—Q relationship. The distinctive responsiveness to hypothermia between humans and natural hibernators may be due to differential neurological and biochemical regulation of Tb, both of which act via mechanisms related to thermogenesis and heat loss. Thermoregulation and the role of thermogenic and heat loss effectors is therefore addressed in the following section.

2.2. Thermoregulation following a shift in the thermoneutral zone

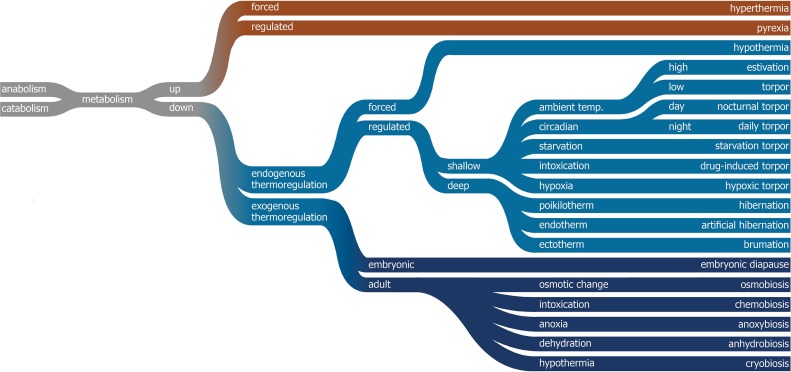

The chief role of thermoregulation is maintenance of Tb to support an optimal thermodynamic environment for all chemical reactions in the organism, which is around 37 °C in humans. Thermogenic control is believed to rely on several neurological pathways, which includes involvement of the preoptic anterior hypothalamus (POAH). Together, these pathways manage a thermoneutral zone (Ztn) which provides a range in which the Tb is to maintain itself, and outside of which the Tb is to be adjusted towards the Ztn through the use of thermogenic effectors and heat loss effectors (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The relationship between the thermoneutral zone and temperature. (A) Overview of thermoregulatory processes. The Ta—Tb relationship represents heat exchange between ambient (Ta) and body temperature (Tb). Information on the Ta is processed and translated into a thermoneutral zone (Ztn) through the Ta—Ztn relationship, whereby the Ztn maintains Tb by regulating thermal effector activity via the Ztn—Tb relationship. (B) Summary of thermal effectors that are mediated by the Ztn—Tb relationship. The Ztn activates thermogenic processes (red) when the Tb < Ztn and heat loss mechanisms (blue) when the Tb > Ztn.

Although it is difficult to ascertain that a single location among the thermoregulatory pathways can have an effect on the Ztn, it is generally accepted that the POAH exerts such an effect in hibernating and non-hibernating animals based on indirect experimental and clinical evidence [23,24]. In humans, incidental but selective destruction of the hypothalamic region is associated with dysfunctional thermoregulation, as evidenced by passive Tb declines to as low as 29 °C [25-29]. Moreover, exposure of hypothalamically impaired patients to low Tas causes a drop in Tb, whereas the same conditions induce a rectifying rise in Tb in ‘control’ subjects [28,30], attesting to impaired thermoregulatory capacity in hypothalamically afflicted patients. Altogether, these reports provide compelling evidence for a temperature integration site in the hypothalamus through which management of Ztn and Tb ensures maintenance of euthermia.

On the basis of these findings it can be concluded that POAH-affected subjects exhibit a sensory defect between Ztn— Ta (Figure 3A), as a result of which Tb will approximate Ta in the absence of thermoregulation. Contrastingly, healthy subjects exhibit a reactive effect between Ztn—Tb, whereby Tb is sustained in conformity with the Ztn irrespective of the Ta via activation of thermogenic effectors (Figure 3B). Accordingly, these data imply that, under normophysiological circumstances, Q is mainly regulated by the Ztn via Ztn—Tb—Q such that the optimal thermodynamic conditions (37 °C) are at all times maintained. POAH-mediated thermoregulation also takes place in rodents that are capable of entering a state of torpor. Corroboratively, selective infarction of the anterior hypothalamus in rats coincides with the inability to regulate Tb, indicating destruction of pathways that govern the Ztn and abrogation of thermoregulatory function [31].

As opposed to humans, Ztn management in smaller animals (e.g., rodents) may veer from a euthermic regime in some species due to specific changes in environmental conditions. One exemplary condition is hypoxia, which is addressed in section 2.3 to illustrate the relationship between S (oxygen) and Q.

Before moving to the S—Q relationship in the context of hypoxia, however, it is imperative to address hypothermia as a function of an organism’s surface:volume ratio, or the ease with which heat exchange between Tb—Ta can proceed. Small animals have a high surface:volume ratio compared to large animals, which allows for faster heat dissipation and results in subsequent lowering of Tb when exposed to cold environments. A high convective efficiency is essential for the induction of hypothermia, and is dependent on the heat loss properties such as the animal’s skin phenotype, breathing pattern, the extent of skin exposure, and the animal’s posture and physical activity [32]. In addition to such effects, small animals require a higher metabolic rate than larger animals to sustain their Tb (Kleiber’s law [33]), which causes small animals to become more easily affected by low Tas. As a result, it takes considerably less time to lower the Tb and coincidentally the Q of a mouse compared to those of a human. This effect is reflected in the strong correlation between the ability and depth of hibernation and surface:volume ratio, which indicates that virtually all hibernating animals are small (i.e., high surface:volume ratio) and that increased body size is associated with a decreased depth of the Tb drop during hibernation/torpor [34]. Hence it appears that environmental/biochemical modulation of metabolism is more prevalent in small animals and subject to the effectiveness of Tb—Ta heat exchange.

2.3. Hypoxia-induced hypometabolism: aligning anabolism with catabolism

The relationship between S and Q is to an extent regulated by the intracellular oxygen tension insofar as oxygen constitutes a vital S for Q (Figure 4). During hypoxia, Q is impaired because of insufficient oxygen availability for oxidative phosphorylation, resulting in reduced cytochrome c oxidase function [35] and cessation of ATP production (A). Under hypoxic but normothermic conditions, the ATP consumption rate (C) can be suppressed to match the ATP production rate, but only to a limited extent and for a short time [36]. In order to survive during a long period of normothermic hypoxia, an organism’s metabolism must remain active to fuel metabolically vital processes, which include protein synthesis (25-30% of total ATP consumption), ion homeostasis (23-36%), gluconeogenesis (7-10%), and ureagenesis (3%) [37]. The limited production yet active consumption of ATP during normothermic hypoxia therefore forces the organism to initially switch to anaerobic respiration (Pasteur effect) - a switch that imposes limits on the maximally tolerable duration of hypoxia/anoxia due to inefficient ATP yields from glycolysis and the production of toxic metabolites such as lactic acid.

Figure 4. Effects of hypoxia on metabolism. Metabolism (Q) is controlled by substrate (S) availability. Lowering of oxygen availability (hypoxia) directly inhibits anabolism (A, i.e., ATP production) but not catabolism (C, i.e., ATP consumption). Consequently, the metabolic tolerance of hypoxia is limited by the extent to which C can be sustained in the absence of A.

In several non-hibernating species, exposure to a prolonged period of hypoxia concurs with regulated hypothermia and hypometabolism, suggesting that hypoxia-mediated thermogenic and metabolic suppression constitutes a protective/ coping mechanism for such life-threatening conditions [38-41]. This hypoxic stress response, illustrated in Figure 5, is in fact an effective survival mechanism in that the catabolic rate is realigned with the limited anabolic rate caused by hypoxia, which is in part achieved by the lowering of Tb through the inhibition of thermogenesis and activation of heat loss mechanisms (explained in section 2.4). In that respect, the hypoxic stress response essentially embodies a pre-programmed manifestation of Arrhenius’ law. During this process, the Ztn must either shift downward or be biochemically inhibited in order to resolve the incongruity between the hypothermic Tb and the euthermically ranged Ztn. A reduction in Tb (and consequently Q) resulting from a downward adjustment of the Ztn is referred to as anapyrexia (Figure 6A), as opposed to pyrexia, which comprises an elevated Tb as result of an elevated Ztn (i.e., fever). How anapyrexia is mediated under hypoxic conditions in animals is elusive. The effect of anapyrexia on thermoregulatory effectors, on the other hand, is not and provides useful information on the hypoxia-anapyrexia signaling axis.

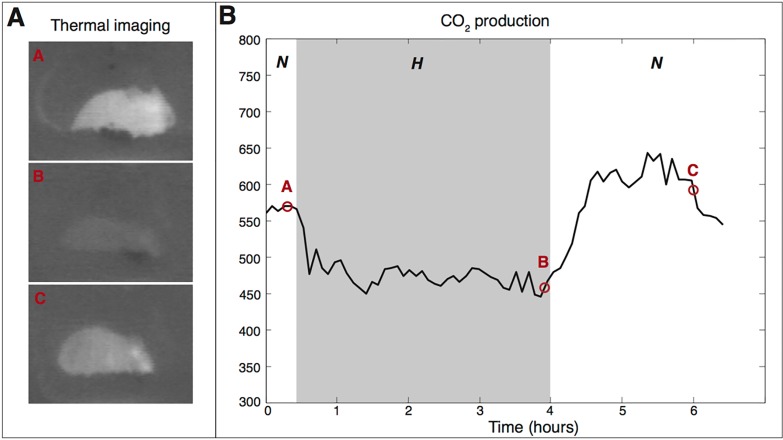

Figure 5. Induction of hypometabolism by hypoxia in mice. An experiment was conducted that exemplifies the reduction in temperature (measured with a thermal camera) and metabolism (measured by exhaled CO2 levels) following exposure of mice (Mus musculus) to hypoxia. The mouse was placed in an air-tight container with an inlet coupled to a gas cylinder containing either an O2:N2 mixture of 21% O2 (to induce normoxic conditions, N) or an O2:N2 mixture of 5% O2 (to induce hypoxic conditions, H). The container was purged with the normoxic or hypoxic gas mixture at a flow rate of 1 L/min. The container also had a gas outlet that was coupled to a CO2 sensor (model 77535 CO2 meter, AZ Instrument, Taichung City, Taiwan). After a 30-min stabilization period under normoxic conditions, hypoxia was induced for 3.5 h, after which the container was changed back to normoxic conditions and the mouse was allowed to recover for an additional 3 h. The ambient temperature (Ta) was maintained at 23.4 ±0.3 °C. During the experiment the mouse was imaged with a thermal camera (Inframetrics, Kent, UK), whereby dark pixels indicate low temperatures and light pixels indicate high temperatures. The frame designations correspond to the lettering in the CO2 production chart to indicate the time point and phase at which the images were acquired. Upon induction of a hypoxic environment, the body temperature (Tb) of the mouse dropped (B), as evidenced by the decreased Tb-Ta contrast between 0.5 h and 4 h. Following restoration of normoxic conditions (C), the animal’s Tb gradually returned to baseline levels. The right panel shows the CO2 profile during normoxia and hypoxia, whereby the hypoxic phase is clearly associated with reduced levels of exhaled CO2, which constitutes a hallmark of hypometabolism.

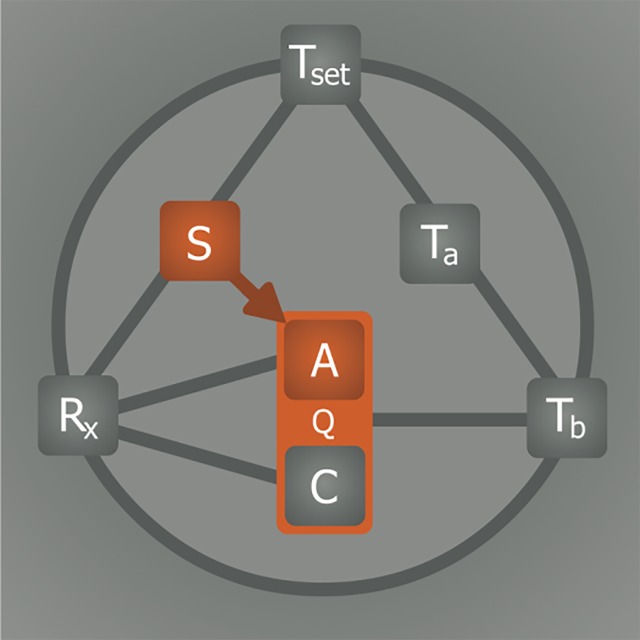

Figure 6. Hypoxia-induced hypometabolism via anapyrexic signaling. (A) The onset of hypoxia, i.e., low substrate (S = oxygen) levels, is proposed to modulate the thermoneutral zone (Ztn) downward via a so-called hypoxic link. The lowering of the Ztn inhibits thermogenesis and activates heat loss mechanisms through the Ztn—Tb relationship, allowing heat exchange between body temperature (Tb) and ambient temperature (Ta) to occur. The consequent reduction in Tb slows down both anabolic (A) and catabolic (C) metabolism (Q) as described in Figure 2. (B) Pathways leading to anapyrexia via the Rx—Ztn and S—Ztn relationships. Although this relationship is exemplified for hypoxic conditions, where S comprises oxygen, it may also apply to conditions where another S is reduced, such as glucose during periods of starvation. Prolonged hypoglycemia is known to also induce hypometabolism, as addressed in section 2.5.4. A direct anapyrexic pathway is suggested for Rx—Ztn, where a neuroactive agent such as delta-opioids directly lowers the Ztn (section 2.5.5). Alternatively, an Rx such as H2S can also affect the Ztn without affecting S availability by inducing hypoxic signaling through oxygen sensors such as carotid bodies (section 2.5.1).

2.4. The effect of hypoxia-induced anapyrexia on thermoregulatory effectors

Hypoxia-induced anapyrexia is found in a large number of species, including mice [39,42], hamsters [43], rats [38,44], pigeons [45,46], dogs [42,47], primates [41], and man [42], and manifests itself when the organism is concurrently exposed to low Ta. A low Ta appears to be a prerequisite for an anapyrexic response to hypoxia, as an anapyrexic response during hypoxic euthermic conditions is absent. The main question, however, is how hypoxic signaling decreases the Ztn to facilitate hypothermia.

The answer may entail an effect of hypoxia on thermogenic effectors (Figure 6A), such as BAT and shivering (Figure 3B). The inhibitory effects of hypoxia on the intensity of cold-induced BAT activity include a lower afferent blood flow to BAT [48], reduced sympathetic nerve activity [49], desensitized response to norepinephrine (a potent BAT activating agent [50,51]) [52], and can eventually lead to a reduction in BAT mass during prolonged exposure to hypoxia [53,54]. In addition, hypoxia results in the inhibition of shivering upon exposure to low Ta compared to normoxic controls in mice, dogs, and man [42]. Moreover, some species further reduce their Tb through changes in behavioral patterns, such as disengagement from cold-induced huddling [55] or exhibiting an explicit preference for cooler environmental temperatures [56].

Considering these effects, it can be hypothesized that hypoxia either acts directly on BAT and muscle tissue (shivering) or indirectly inhibits these thermogenic effectors via central regulation, the Ztn. The latter is a more likely mechanism of action since anapyrexic signaling controls both BAT and shivering in order to facilitate hypothermia. Poor blood oxygenation, a result of exposure to hypoxia, is relayed to the brain via the carotid bodies, which is described by a Rx—Ztn relationship (Figure 6B). CBs are oxygen sensing bodies located alongside the carotid artery that contain oxygen-sensitive chemoreceptors through which they provide essential neuronal feedback on the arterial partial oxygen pressure [57]. Excitation of the CBs by reduced oxygen levels during hypoxia possibly induces lowering of the Ztn to activate heat loss effectors(Figure 3B) so as to facilitate the induction of hypothermia with the sole purpose of aligning ATP consumption rates with ATP production rates as part of the survival response to stress conditions (section 2.3). Naturally, this response prevails in species that have a sufficiently high Ta—Tb convective efficiency to allow rapid manifestation of hypothermia and corollary reduction in Q (section 2.2), given that sustenance of life by anaerobic metabolism is time-limited. CBs are therefore an important instrumental component of the ‘hypoxic link’ in smaller species.

The existence of a ‘hypoxic link’ to the Ztn (Figure 6) has been suggested [58] but lacks direct evidence other than the previously mentioned changes in thermal effectors. This link implies that, under cold but normoxic conditions, the Ztn enforces an array of physiological tools that coordinate a thermogenic response, such as shivering, activation of BAT, vasoconstriction, and piloerection (Figure 3B). Under hypoxic conditions, however, these thermogenic responses are dampened or even absent and coincide with activation of heat loss effectors such as vasodilation, sweating, and panting (Figure 3B) [58]. Direct measurement of changes in the Ztn range would be useful in substantiating the ‘hypoxic link.’ Unfortunately, due to incomplete knowledge of Ztn functionality and technical difficulties related to reaching the neural pathways involved, it is currently very difficult to directly measure the range of the Ztn or changes therein.

In summary, hypoxia (low S levels) leads to hypometabolism potentially by signaling anapyrexia through CBs, thereby allowing the body to cool via the S—Ztn—(Ta—)Tb—Q relationship. The hypoxia-induced anapyrexic component provides an advantage over the Tb—Q relationship in that the anapyrexia allows the Tb to drop below normothermia, preventing the stress response that would otherwise be needed to keep the body normothermic. Nevertheless, it is unlikely that these pathways constitute all necessary conditions for the induction of natural hibernation. A closer look at (bio)chemical agents (Rx) that have the ability to induce or mimic ‘anapyrexiadriven hibernation’ present additional pathways, namely through their effect on S availability, the relay of S availability to the Ztn, and through direct effect on Ztn.

2.5. Pharmacological agents and induction of artificial hypometabolism

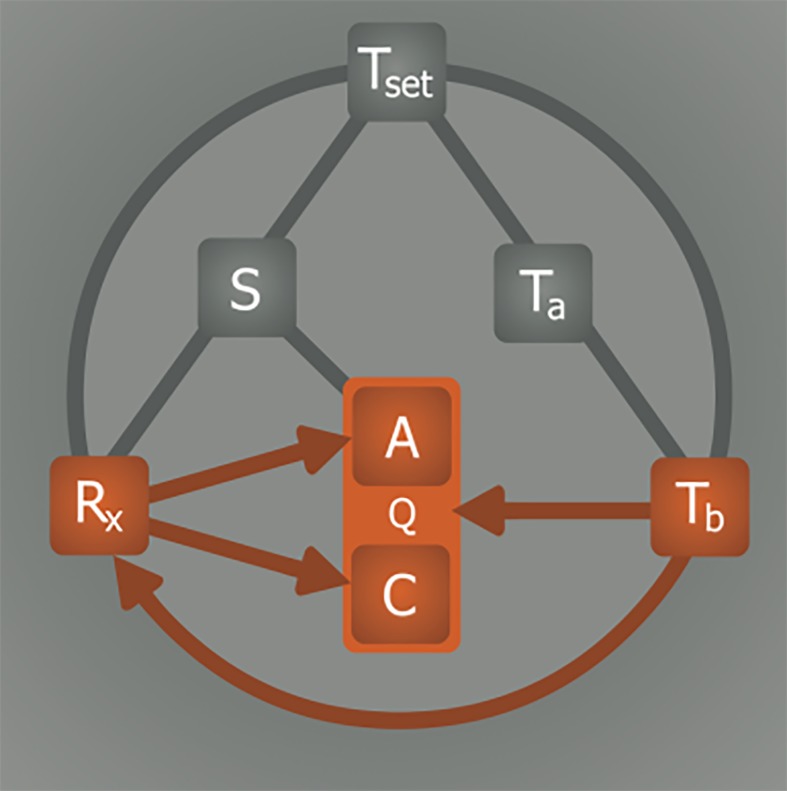

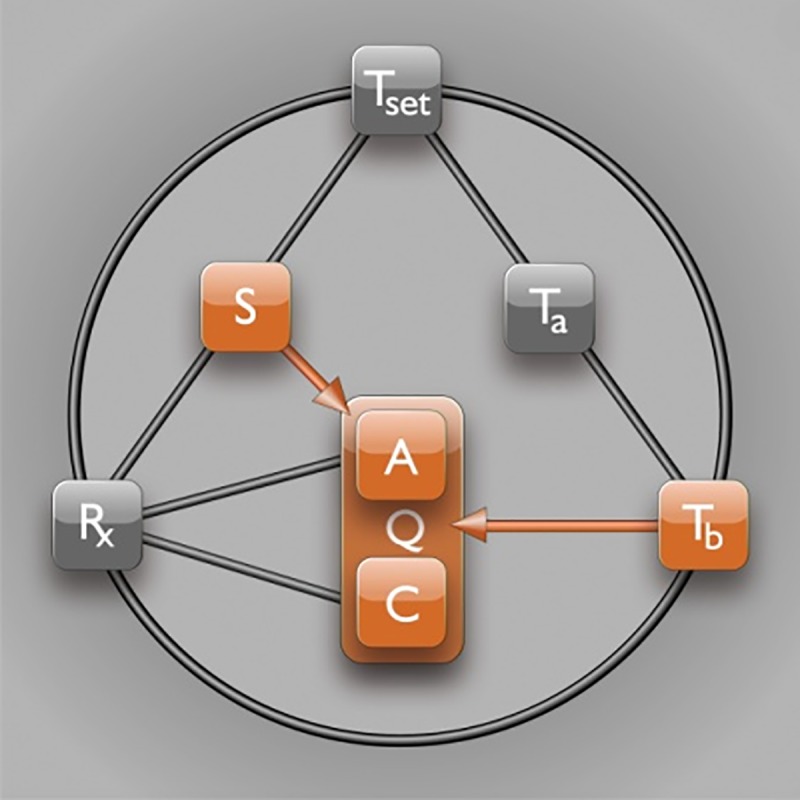

Induction of hypometabolism in natural hibernators normally occurs in response to environmental triggers such as low Ta and light and/or food deprivation. The internal (bio)chemical trigger responsible for the subsequent propagation of this signal is key to understanding the hibernation process. It has been suggested that a yet to be characterized endogenous molecular compound, referred to as hibernation induction trigger (HIT), is responsible for inducing hibernation in vivo [59,60] via the Rx—Q(—Tb) relationship, whereby the drop in Tb is arguably a consequence of the reduced Q by the HIT (Figure 7). It should be noted that this mechanism would differ fundamentally from anapyrexic signaling, which requires Ztn downmodulation and subsequent Ta—Tb equalization as a precursor event for hypometabolic induction (Figure 6). In an effort to identify the HIT, different endogenous compounds have been investigated that have potential to account for or mimic the effect of the HIT, including H2S [3], 5’-adenosine monophosphate (5’-AMP) [61], thyronamines (TAMs) [6], 2’-deoxyglucose (2-DG) [4], and delta-opioids (DOPs) [5, 59].

Figure 7. The effect of hibernation induction trigger on metabolic activity. It has been suggested that metabolism (Q) may be directly inhibited by pharmacological agents (Rx) such as hibernation induction trigger (HIT) via inhibition of anabolism (A) and/or catabolism (C). It should be underscored that, based on the information presented in sections 2.2 and 2.4, this pathway is unlikely to occur in the absence of hypothermic signaling via Ztn downmodulation.

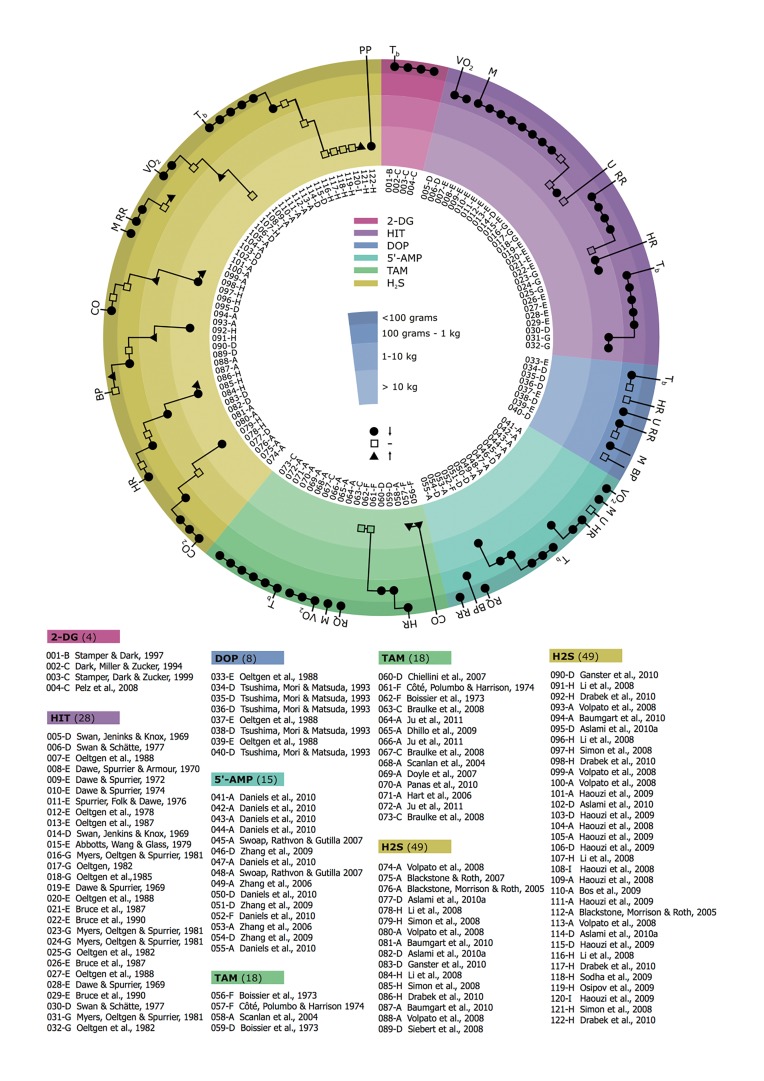

Although induction of a hypometabolic state is a shared trait of these agents, each is associated with a different pattern of physiological effects. The physiological effects related to hibernation, as summarized in Figure 8, are primarily found in small animals (Figure 8, outer ring) and not so much in large animals (Figure 8, inner ring). The high incidence of hypometabolic effects in small animals suggests that part of the Rx mechanism may rely on anapyrexia according to the Rx— (S)—Ztn—Tb—Q relationship described in Figure 6, and underscores the importance of the surface:volume ratio (section 2.2). Consequently, the currently identified hypometabolism-inducing agents are addressed in relation to their direct anapyrexic properties (Rx—Ztn), their indirect anapyrexic properties (Rx—S—Ztn), or their substrate affecting properties (S—A).

Figure 8. Physiological effects of hibernation inducing agents. Overview of physiological effects in response to 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG), 5’-adenosine monophosphate (5’-AMP), hydrogen sulfide (H2S), hibernation induction trigger (HIT), delta-opioid (DOP), and thyronamine (TAM). Each effect is represented by a black dot (lowering of value), transparent square (equal value), or black triangle (rise of value). The effects are stratified according to the size of the animal, from outer ring to inner ring these are: < 0.1 kg (e.g., mouse), 0.1-1 kg (e.g., rat), 1-10 kg (e.g., macaque) and > 10 kg (e.g., pig). The inner white ring indicates the respective reference (number) and species (letter). Animals: A, house mouse (Mus musculus, Linnaeus), B, deer mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus, Wagner); C, djungarian hamster (Phodopus sungorus, Pallas); D, common rat (Rattus novergicus, Berkenhout); E, thirteen-lines ground squirrel (Spermophilus tridecemlineatus, Mitchill); F, domestic dog (Canis lupus familiaris, Linnaeus); G, rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta, Zimmermann) or southern pig-tailed macaque (Macaca nemestrina, Linnaeus); H, domestic pig (Sus scrofa domesticus, Erxleben); I, sheep (Ovis aries, Linnaeus). The physiological parameters include: Tb, core body temperature; VO2, oxygen consumption; M, motion; RR, respiratory rate; HR, heart rate; U, urine production; BP, blood pressure; RQ, respiratory quotient; CO, cardiac output; CO2, carbon dioxide production; PP, pulmonary pressure. All parameters are expected to be reduced during hypometabolism.

2.5.1. Hydrogen sulfide

Exposure to H2S consistently produces a hypometabolic state in small animals such as mice and rats (Figure 8, outer ring) [3,62-66]. However, the use of H2S in larger animals such as pigs [67-70], sheep [65], and heavy rats [71] has failed to induce a hypometabolic response (Figure 8, inner ring). The current mechanistic paradigm of the hypometabolic effect of H2S is based on its high membrane permeability and direct inhibitory effect on cytochrome c oxidase in the electron transport chain (i.e., through the Rx—A relationship) [72,73]. However, increasing evidence indicates the hypometabolic effects are the result of hypoxic signaling. For example, endogenously produced H2S is necessary for CBs to signal hypoxia [74]. Exogenously applied H2S, via a soluble NaSH precursor, can mimic the production of this hypoxic signal in vitro [75], suggesting the utilization of the ‘hypoxic link’ (Rx—Ztn) by H2S (Figure 6B). This is supported by the observed dichotomy between H2S-induced effects in small versus large species, where H2S produces hypometabolic effects in small species but not in larger species (Figure 8). The Rx—Ztn—Tb—Q relationship is dependent on a high Ta—Tb convective efficiency; a property that prevails strictly in small species due to their high surface:volume ratio (section 2.2).

2.5.2. Adenosine monophosphate

Intraperitoneal injections of 5’-AMP have been shown to induce an artificial hypometabolic state in mice and rats as evidenced by a profound drop in Tb (Figure 8) [61,76-78]. The putative contention is that intraperitoneal administration of high 5’-AMP concentrations (e.g., 500 mg/kg) lead to extensive 5’-AMP uptake by erythrocytes [79], after which the high intracellular levels of 5’-AMP drive the adenylate equilibrium (ATP + AMP ↔ 2 ADP) towards production of ADP, thereby depleting erythrocyte ATP levels [76,77]. As a result, erythrocyte 2,3-disphosphoglycerate is upregulated, limiting the binding of oxygen to hemoglobin’s oxygen binding sites (referred to as oxygen affinity hypoxia) [76]. In addition to the already impaired oxygen transport, the severe cardiovascular depression following 5’-AMP administration has the potential to further exacerbate this hypoxic state (referred to as circulatory hypoxia) [78]. Although there is no conclusive evidence that these types of hypoxia have the ability to induce an anapyrexic state, the generally pervasive hypoxic state likely uses the S—Ztn—Tb(—Ta)—Q relationship (Figure 6A) to induce hypometabolism through CB signaling.

More recent studies have implicated a direct 5’-AMP signal transduction route to the central nervous system in seasonal hibernators, culminating in the induction of torpor [80-83]. 5’-AMP signaling occurs via the A1 adenosine receptor (A1AR), which is ubiquitously distributed throughout all tissues, but not the A2aAR or A3AR receptors. In the brain, A1AR signaling leads to deceleration of metabolic rate and induction of a torpor state in arctic ground squirrels [84]. In this species, intracerebroventricular administration of the A1AR antagonist cyclopentyltheophylline reversed spontaneous entrance into torpor during hibernation season, whereas administration of the A1AR agonist N(6)-cyclohexyladenosine induced torpor [82]. Later studies confirmed the manifestation of 5’-AMP-driven torpor in non-hibernators, including the mouse [80] and rat [83], suggesting that the hypothermia- and hypometabolism-inducing potential of 5’-AMP is pleiotropically applicable across species. Although the signaling is of more direct neurochemical nature compared to the hypoxic signaling, the S—Ztn—Tb(—Ta)—Q relationship (Figure 6A) also holds for the 5’-AMP-A1AR signaling axis.

As indicated previously, the depth of the hypometabolic response is dependent on the Tb—Ta convective efficiency (section 2.2). This is further supported by the extent of the drop in Tb that is observed in 5’-AMP-treated mice, which is proportional to the difference between Tb and Ta (i.e., lower Tas induce a greater drop in Tb), demonstrating the Tb—Ta dependency [76].

2.5.3. Thyronamines

TAMs are a thyroid hormone-derived group of compounds of which currently nine structural analogues have been identified [6]. Contrary to the structurally similar metabolism- enhancing thyronines (T3 and T4), exposure to TAM analogues triggers a transient Tb depression in small animals, epitomizing the induction of a hypometabolic phase (Figure 8) [6,85-88]. Although earlier studies in a canine model presented contradictory evidence with respect to metabolic effects compared to later studies (Figure 8, cardiac output), it is likely that this was a result of differences in synthesis methods and compound purity [87,89]. Nevertheless, the metabolic effects of TAMs remain obscure, regardless of the synthesis method.

Both in vivo and ex vivo studies have found the physiological effects of TAMs to be mainly cardiogenic in nature, producing severe hemodynamic depression, bradycardia, hypotension, and reduced cardiac output [6,85,90]. These effects result in reduced oxygen levels (affecting the Rx—S—Ztn relationship, Figure 6) by lowering the extent of blood oxygenation in accordance with Fick’s principle, which describes an inverse relationship between cardiac output and oxygenation (circulatory hypoxia) [91, 92]. Although the effect of circulatory hypoxia on the Ztn has not been demonstrated, the presence of hypoxia in the broader sense may support the implication of the S—Ztn—Tb(— Ta)—Q relationship (Figure 6A) as a basis of the observed hypometabolism in smaller animals.

Given the magnitude of the hemodynamic collapse in small species, TAMs may additionally render the animal motionless (Figure 8, motion), which would facilitate a greater rate of thermal convection (Tb—Ta) and therefore accelerate the consequent reduction in Tb and Q (Figure 2).

2.5.4. Deoxyglucose

In addition to oxygen, S can also comprise glucose, as evidenced by the induction of a hypometabolic state upon glucose deprivation in hamsters and various types of mice [4, 93-95]. Shortage of food, and with that the ability to use glucose as energy substrate, has the potential to induce hypometabolism or alter its depth [94-96]. This principle has been demonstrated in hamsters using 2-DG, a glucose analogue that cannot undergo glycolysis as a result of the 2-hydroxyl group, which causes the animals to enter a hypometabolic state [4,93]. The hypometabolic response to 2-DG, measured by the drop in Tb, is reflective of the S—A relationship (Figure 4). Currently there is no evidence that supports the S—Ztn pathway for 2-DG.

2.5.5. Delta-opioids

Isolation and characterization of the HIT found in serum of hibernating woodchucks and squirrels revealed a resemblance to D-Ala-D-Leu-5-enkephalin, a non-specific DOP receptor agonist [5,97]. Consistent with this characterization, DOPs induce a hypometabolic state of similar depth as the HIT, whereas mu- or kappa-opioid receptor agonists show no effect [97,98]. The involvement of opioid receptors is further substantiated by the inability of DOP to induce hypometabolism upon exposure to naloxon, a non-specific opioid receptor antagonist [99-102]. These findings raise the question whether DOPs make use of a direct Rx—Q relationship or act via the Rx—Ztn (Figure 6). Growing evidence suggests the latter, as delta-opioids appear to be directly involved in hypoxic signaling. In mice, exposure to hypoxia has been suggested to decrease Ztn via delta-1-opioid receptor agonism [103-106]. Other studies have suggested that the delta-2 opioid receptor rather than a delta-1 opioid receptor is responsible for the effects on the Ztn [107-109], supported by the limited presence of delta-1-opioid receptors in the hypothalamic region [110,111]. However, in both cases the preferred pathway to Ztn modulation appears to involve a direct Rx—Ztn relationship.

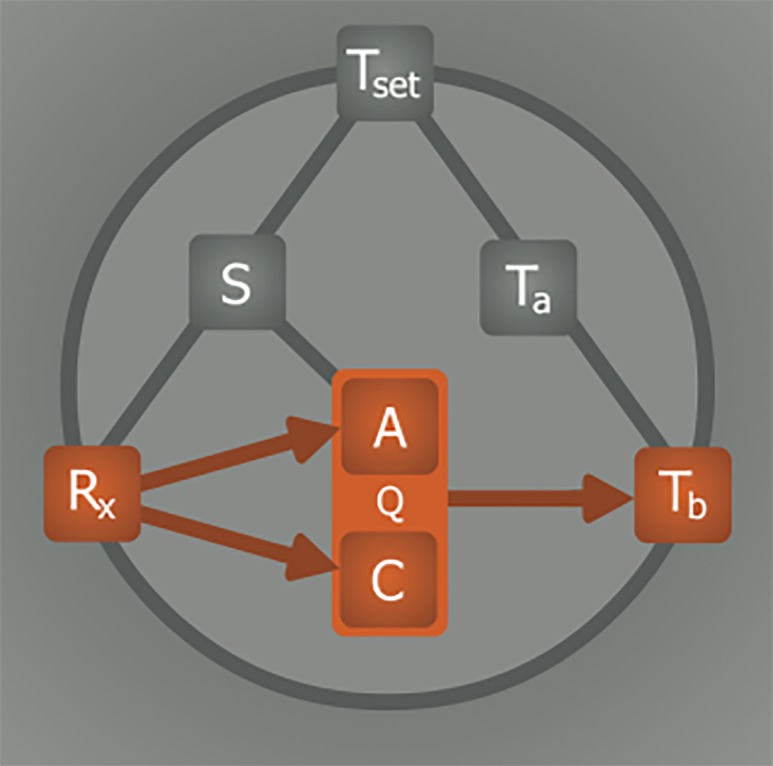

2.6. Pharmacological agent properties and the feedback loop

As demonstrated by the different mechanisms discussed in the previous section, Rx can affect Q via three potential pathways, namely via Rx—Q(—Tb) (Figure 7, suggested for HIT), via Rx—S—Ztn—Tb—Q (Figure 6, suggested for H2S, 5’-AMP, TAM, and 2-DG), and via Rx—Ztn—Tb—Q (suggested for DOP). However, irrespective of the hypometabolic pathway, it is unlikely that the systemic release of a single Rx accounts for the hypothermic/hypometabolic induction process. Instead, as is the case in many biochemical pathways, it is more probable that the induction of hypometabolism is governed by a signal amplifying feedback loop (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Signal amplifying feedback loop during hypometabolic induction. Theoretically, lowering of the body temperature (Tb) could be part of a feedback system that triggers the release of a metabolism inhibiting agent (Rx) capable of further lowering metabolism (Q) via direct inibition of anabolism (A) and/or catabolism (C). This process is embodied by the Tb—Rx— Q relationship.

With respect to the model, the ideal properties of an Rx regarding its regulatory function of the feedback loop encompass 1) endogenous production and/or release during induction of hibernation, 2) inhibitory effects on both A and C, 3) downregulatory effect on Ztn, 4) equal distribution throughout the body, and 5) availability of agonists and antagonists to accelerate and abrogate Rx-mediated signaling, respectively. Although currently there is no sound evidence for the existence of an Rx feedback loop, such a mechanism is theoretically necessary to propagate a hypometabolic signal in vivo. Consequently, a mechanistic framework for such a feedback loop will be elaborated for magnesium (Mg2+), which appears to play an important role in hibernation across different species.

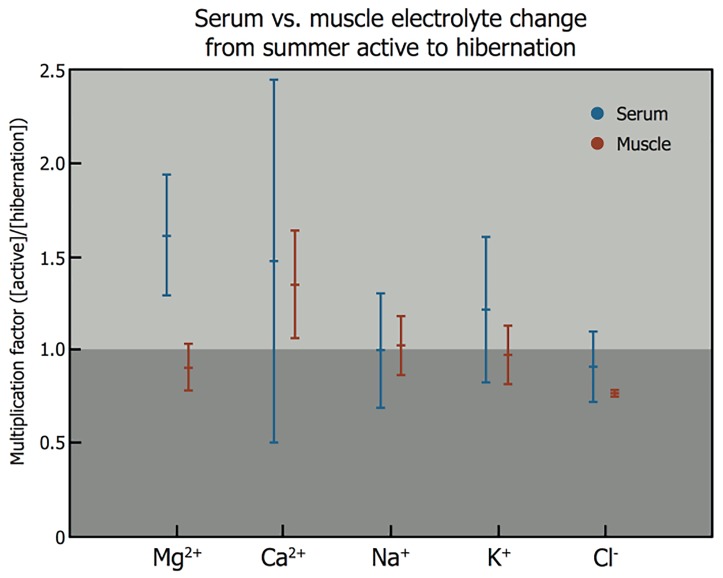

Induction of hibernation coincides with a change in serum Mg2+ concentration (Figure 10). Serum Mg2+ levels increase by an average of 1.6-fold upon induction of hibernation in different species compared to their summer active state, which is a considerably higher increase than observed for other electrolytes. The release of Mg2+ into the circulation occurs from storage pools that have formed prior to induction of hibernation in cells that comprise muscle (Figure 10) and skin tissue [112, 113]. The translocation of Mg2+ from tissue to blood and subsequent systemic distribution is in conformity with the first Rx property, i.e., the release of an endogenous agent during the induction of hibernation.

Figure 10. Electrolyte changes during induction of natural hibernation. Analysis of blood levels of magnesium (Mg2+, serum n = 23, muscle n = 9), calcium (Ca2+, serum n = 19, muscle n = 5), sodium (Na+, serum n = 16, muscle n = 6), potassium (K+, serum n = 25, muscle n = 9), and chloride (Cl−, serum n = 9, muscle n = 3) from summer active state to hibernation (< 1, reduction upon induction into hibernation; 1, no change; > 1, increase in electrolyte concentration). Black bars correspond to serum electrolyte levels, grey bars indicate electrolyte levels in muscle tissue. Animals included in this figure are: European hedgehog (Erinaceus europaeus, Linnaeus) [114-116], long-eared hedgehog (Hemiechinus auritus, Gmelin) [117], golden hamster (Mesocricetus auratus, Waterhouse) [118-122], common box turtle (Terrapene carolina, Linnaeus) [123], pond slider (Trachemys scripta, Thunberg) [123], painted turtle (Chrysemys picta, Schneider) [124-127], European ground squirrel (Spermophilus citellus, Linneaus) [128], thirteen-lined ground squirrel (Spermophilus tridecemlineatus, Mitchill) [121, 122, 129], groundhog (Marmota monax, Linneaus) [130, 131], yellow-bellied marmot (Marmota flaviventris, Audubon & Backman) [132], Asian common toad (Duttaphrynus melanostictus, Schneider) [133], little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus, LeConte) [122, 134, 135], big brown bat (Eptesicus fuscus, Palisot de Beauvois) [122;134], American black bear (Ursus americanus, Pallas) [122], common musk turtle (Sternotherus odoratus, Latreille) [136], desert monitor (Varanus griseus, Daudin) [137]. Statistical analysis was performed in MatLab R2011a. Intragroup analysis of serum versus muscle electrolyte levels (Mann-Whitney U test: p-value): Mg2+, p < 0.001; Ca2+, p = 0.395; Na+, p = 0.299; K+, p = 0.067; Cl−, p = 0.315. Intergroup analysis of serum electrolyte levels, indicating statistical differences (Kruskal-Wallis test): Mg2+ versus Ca2+, Na+, K+, and Cl−, (p < 0.05).

In regard to the second property, Mg2+ exerts an inhibitory effect on Q, affecting both A and C. Mg2+ acts as a necessary co-factor in over 300 enzymatic reactions[138]. When the Mg2+ concentration exceeds the saturating concentration required for occupying all substrate binding sites, Mg2+ becomes an inhibitor of enzymatic activity [138]. The inhibitory properties of Mg2+ are not limited to the inhibition of A, such as reduction of state III respiration (ADP-stimulated respiration) upon exposure to Mg2+ [139], but also include inhibition of C, such as reduction of Na/K-ATPase activity [140]. In addition, Mg2+ inhibits ion channels, such as the NMDA receptor ion channel and voltage gated ion channels [141-143]. Although inhibition of A and C are essential in sustaining a prolonged state of hypometabolism, as occurs during hibernation, this Rx property has been largely ignored in reports on conventional hibernation-inducing Rx agents (i.e., H2S, 5’-AMP, TAM, 2-DG, and DOP).

The third property of an Rx is its downward adjusting effect on the Ztn. In case of Mg2+ there appears to be conflicting evidence; intracerebroventricular perfusion with a solution containing a supraphysiological concentration of Mg2+ does not result in a hypothermic response in hamsters [144], rats [145], cats [146-148], and primates [149, 150] but does result in a hypothermic response in pigeons [151], dogs [152], and sheep [153]. However, with this perfusion approach it cannot be guaranteed that intracerebroventricular perfusion solely affected the neural pathways involved in thermoregulation. A more accurate assessment can be made on the basis of the thermal effectors, in which case Mg2+ exerted an inhibitory effect on shivering in cold-exposed dogs [154], reduced postanesthetic shivering in patients [155-157], lowered the coldinduced shivering threshold in healthy human subjects [158], and promoted heat loss effectors in rats [159]. Essentially, these reports constitute indirect evidence for the Ztn lowering property of Mg2+, which is manifested through the activation of heat loss mechanisms and inhibition of thermogenic mechanisms (Rx— Ztn—Tb, Figure 6).

Fourth, an Rx must distribute throughout the entire body. Although self-evident, this property is often omitted in common theories on the induction of hibernation by pharmacological agents. Heterogeneously distributed receptors of an Rx deter widespread propagation of hypometabolic signaling, and instead support hypometabolic signaling through an interposed effect such as the lowering of the Ztn (e.g., DOP) or the availability of S (e.g., TAM). The systemic distribution of Mg2+ is unclear, but is expected to be ubiquitous given the role of this cation in many enzymatic reactions, including in the hexokinase-mediated conversion of glucose to glucose 6-phosphate, which occurs in every somatic cell type as part of sugar metabolism.

Finally, it is important that an Rx is sensitive to stimulation and inhibition for the induction and abrogation of hypometabolic signaling, respectively. The natural factors that trigger hibernation include lowering of Ta and dietary change, both of which are able to increase plasma Mg2+ via cold-stimulated muscular and dermal release of Mg2+ that is stored during the pre-starvation diet period [160]. The subsequent rise in plasma Mg2+ can promote inhibition of thermogenic activity and activation of heat loss mechanisms by lowering of the Ztn, potentiating heat exchange (Ta—Tb). In addition, direct effects on shivering via Mg2+-mediated inhibition of neuromuscular transmission facilitates lowering of Tb [161]. The consequent cooling releases more Mg2+ stored in muscles and skin, further adding to the increase in serum Mg2+ through a positive feedback loop. As discussed in section 2.2, a feedback loop of this type would be most efficient in small animals due to their high body surface:size ratio and result in a less profound Tb drop in larger animals.

2.7. Hypothermia and hypometabolism research and clinical implementation: important considerations

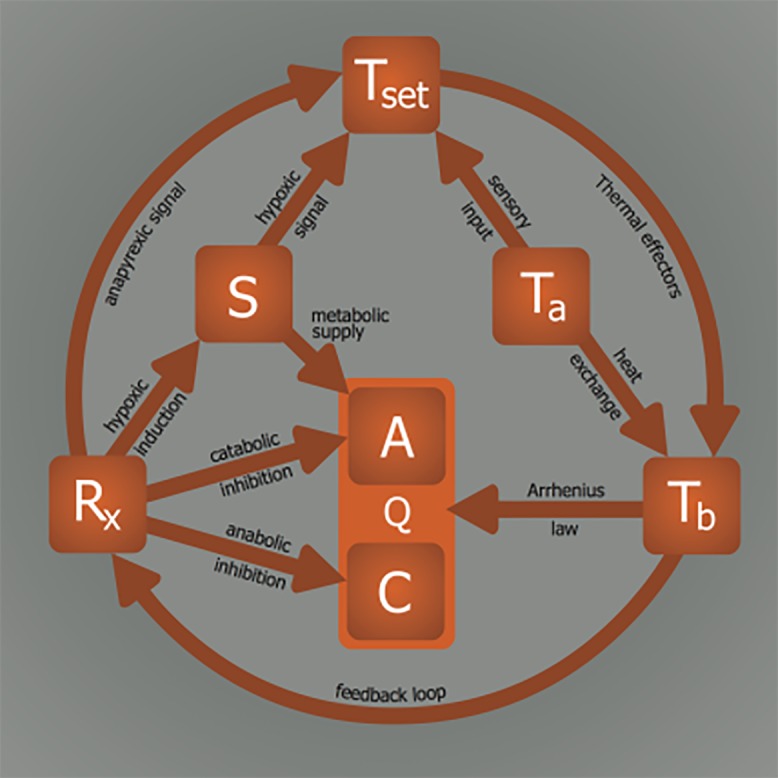

The complete model on the induction of hibernation, presented in Figure 11, is in part hypothetical and requires additional research to validate every relationship. Given the supportive experimental evidence discussed in the previous sections, the model provides a starting framework for interpreting observations made in future in vivo experiments concerning hypothermia and hypometabolism, particularly in the context of integrative physiology. There are several important considerations regarding this type of research that must be accounted for, especially when data are interpreted on the basis of the model.

Figure 11. Model for induction of (artificial) hypometabolism. Depicted parameters: Q, overall metabolism defined as chemical reaction speed (i.e., similar to k in Equation 1); C, catabolism; A, anabolism; Tb, core body temperature; Ta, ambient temperature; Ztn, thermoneutral zone; S, substrate; Rx, (bio)chemical agent able to induce hypometabolism. The relationships: Tb—Q, Arrhenius law; Ta—Tb, heat exchange; Ztn—Tb, thermogenesis and heat loss mechanisms; Ta—Ztn, sensory input; S—Ztn, hypoxic link; Rx— S, hypoxia/hypoglycemia induction; Rx—C, catabolic modulation; Rx—A, anabolic modulation; Rx—Ztn, anapyrexic signal; S—A, metabolic substrate supply; Tb—Rx, positive/negative feedback loop.

As implied in sections 2.1 and 2.2, prevention of stress signaling upon exposure to a cold stimulus is crucial to safe lowering of metabolism, underscoring the need for validation of the Rx—(S)—Ztn relationship. This would require knowledge on both the location and function of the Ztn, which, as alluded to previously, is currently beyond our reach. However, by investigating the impact of a stimulus such as Ta or Rx on thermogenic effectors, heat loss effectors, and behavioral thermoregulation (Ztn—Tb, Figure 3B), the Ztn issues can be circumvented while still gaining insight into the Ztn lowering potency. Ztn-related research is presently conducted in this fashion, whereby ancillary parameters (effectors and behavior) are used as a gold standard to gauge Ztn [58].

Due to their high Ta—Tb convective efficiency, small animals constitute ideal subjects for screening the anapyrexic potential of an Rx or investigating the effects of hypoxia. In larger animals, the lower Tb—Ta convective efficiency necessitates the use of active cooling to accommodate induction of hypothermia and corollary hypometabolism. If active cooling in larger animal models is omitted, an anapyrexic agent or hypoxia may yield hypometabolic results in small animals but induce limited or no effect in larger animals. A totally Tb-independent Rx (i.e., Rx— Q, Tb = 37 °C) would be in contradiction to this model and in fact disprove the necessity of Ta—Tb convection. It is our opinion, however, that hypometabolism cannot occur under normothermic conditions – an opinion that is supported by extension of the Arrhenius law.

When translating these principles to a clinical setting, the use of the Rx(—S)—Ztn relationship suggests that better outcomes would be achieved if hypothermic patients were pretreated with an anapyrexic agent (Rx—Ztn—Tb(—Ta)) or subjected to hypoxia (S—Ztn—Tb(—Ta)). The fact that clinical practice deviates from these approaches may contribute to the increased comorbidity in patients as a result of hypothermia- inflicted stress responses during trauma-induced and perioperative hypothermia [15,162]. Presently, none of the strategies aimed to resolve these responses in patients encompass guidelines for Ztn modulation. As a result, many patients are placed on 100% O2 and symptomatic treatment of shivering without a clear rationale. According to our model, a more cautious approach in oxygenating hypothermic patients could be beneficial, as reflected by the S—Ztn—Tb signaling axis. By subjecting a hypothermic patient to a hypoxic signal (S—Ztn) or anapyrexic agent (Rx(—S)—Ztn), the cold-induced stress response may be mitigated by reduction of Ztn through CB signaling and alignment of Tb with Ta. As exposure to a cold stimulus readily activates thermal effectors such as shivering and BAT[163,164], such an effect would be promptly visible. However, to date no anapyrexic agents or hypoxic signaling mechanisms have been reported in a clinical setting.

3. Conclusions

In conclusion, the lack of understanding of the induction mechanisms underlying natural hibernation stands in the way of successful application of artificial hibernation in biotechnology and medicine. Accordingly, a model was developed to assist in finding the means to translate the physiological changes observed during natural hibernation to its artificial counterpart. Summarized in Figure 11, six essential elements form the basis of our model, which were extrapolated from literature. The relationships between these elements dictate their values and collectively govern the induction and sustenance of a hypometabolic state. To illustrate the potential validity of this model, various Rx (HIT, DOP, H2S, 5’-AMP, TAM, 2-DG, Mg2+) were described in terms of their influence on the intervariable relationships and effects on Q.

Although the ultimate purpose of this hypothetical model was to help expand the paradigm regarding the mechanisms of hibernation from a physiological perspective and to assist in translating this natural phenomenon to the clinical setting, our model only comprises a part of the vastly complex biological systems that underlie anapyrexia and hypometabolism. Moreover, readers should note that concepts as ‘set point’ are model-based phenomena, rather than neurobiological constructs. The key to the mechanistic underpinning of anapyrexic signaling currently rests on the shoulders of neurobiology, which is slowly unveiling the neurological signaling pathways. In that respect, thermal reflexes (cold defense, fever, anapyrexia, hibernation, etc.) are mediated by changes in the discharge of neurons in neural circuits controlling thermoregulatory effectors, and understanding how and through which neurochemical mediators these reflexes are effected will only be accomplished through detailed neurobiological experimentation. Accordingly, basic elucidation of the neurochemistry of anapyrexia is needed for the identification of useful Rxs [81, 82].

Acknowledgements

We thank Inge Kos-Oosterling for support with the graphics.

Abbreviations:

- 2-DG

2-deoxyglucose

- 5’-AMP

5’-adenosine monophosphate

- A1AR

A1 adenosine receptor

- A

anabolism

- BAT

brown adipose tissue

- C

catabolism

- DOP

delta-opioid

- H2S

hydrogen sulfide

- POAH

preoptic anterior hypohalamus

- Q

metabolism

- Rx

pharmacological agent

- S

substrate

- TAM

thyronamine

- Ta

ambient temperature

- Tb

core body temperature

- Ztn

thermoneutral zone

Footnotes

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest present.

References

- [1].Geiser F. Metabolic rate and body temperature reduction during hibernation and daily torpor. Annu Rev Physiol. 2004;66:239–274. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.66.032102.115105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hudson JW, Scott IM. Daily torpor in the laboratory mouse, Musmusculus var. albino. Physiological Zoology. 1979;52:205–218. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Blackstone E, Morrison M, Roth MB. H2S induces a suspended animation-like state in mice. Science. 2005;308:518. doi: 10.1126/science.1108581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Dark J, Miller DR, Zucker I. Reduced glucose availability induces torpor in Siberian hamsters. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:R496–R501. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.267.2.R496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Horton ND, Kaftani DJ, Bruce DS, Bailey EC, Krober AS, Jones JR, Turker M, Khattar N, Su TP, Bolling SF, Oeltgen PR. Isolation and partial characterization of an opioid-like 88 kDa hibernation-related protein. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 1998;119:787–805. doi: 10.1016/s0305-0491(98)00056-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Scanlan TS, Suchland KL, Hart ME, Chiellini G, Huang Y, Kruzich PJ, Frascarelli S, Crossley DA, Bunzow JR, Ronca-Testoni S, Lin ET, Hatton D, Zucchi R, Grandy DK. 3-Iodothyronamine is an endogenous and rapid-acting derivative of thyroid hormone. Nat Med. 2004;10:638–642. doi: 10.1038/nm1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Zhang H, Zhi L, Moore PK, Bhatia M. Role of hydrogen sulfide in cecal ligation and puncture-induced sepsis in the mouse. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290:L1193–L1201. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00489.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Azoulay D, Eshkenazy R, Andreani P, Castaing D, Adam R, Ichai P, Naili S, Vinet E, Saliba F, Lemoine A, Gillon MC, Bismuth H. In situ hypothermic perfusion of the liver versus standard total vascular exclusion for complex liver resection. Ann Surg. 2005;241:277–285. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000152017.62778.2f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Reiniers MJ, van Golen RF, Heger M, Mearadji B, Bennink RJ, Verheij J, van Gulik TM. In situ hypothermic perfusion with retrograde outflow during right hemihepatectomy: first experiences with a new technique. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218:e7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Axelrod YK, Diringer MN. Temperature management in acute neurologic disorders. Neurol Clin. 2008;26:585–603. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Holzer M, Behringer W. Therapeutic hypothermia after cardiac arrest and myocardial infarction. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2008;22:711–728. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bernard SA, Gray TW, Buist MD, Jones BM, Silvester W, Gutteridge G, Smith K. Treatment of comatose survivors of out-ofhospital cardiac arrest with induced hypothermia. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:557–563. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Polderman KH. Application of therapeutic hypothermia in the intensive care unit. Opportunities and pitfalls of a promising treatment modality-Part 2: Practical aspects and side effects. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:757–769. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-2151-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Polderman KH. Mechanisms of action, physiological effects, and complications of hypothermia. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:S186–S202. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181aa5241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Frank SM, Higgins MS, Breslow MJ, Fleisher LA, Gorman RB, Sitzmann JV, Raff H, Beattie C. The catecholamine, cortisol, and hemodynamic responses to mild perioperative hypothermia. A randomized clinical trial. Anesthesiology. 1995;82:83–93. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199501000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Jurkovich GJ, Greiser WB, Luterman A, Curreri PW. Hypothermia in trauma victims: an ominous predictor of survival. J Trauma. 1987;27:1019–1024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Sajid MS, Shakir AJ, Khatri K, Baig MK. The role of perioperative warming in surgery: a systematic review. Sao Paulo Med J. 2009;127:231–237. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31802009000400009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ivanov KP. Physiological blocking of the mechanisms of cold death: theoretical and experimental considerations. J Therm Biol. 2000;25:467–479. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4565(00)00012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ananiadou OG, Bibou K, Drossos GE, Bai M, Haj-Yahia S, Charchardi A, Johnson EO. Hypothermia at 10 degrees C reduces neurologic injury after hypothermic circulatory arrest in the pig. J Card Surg. 2008;23:31–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.2007.00485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Letsou GV, Breznock EM, Whitehair J, Kurtz RS, Jacobs R, Leavitt ML, Sternberg H, Shermer S, Kehrer S, Segall JM, Voelker MA, Waitz HD, Segall PE. Resuscitating hypothermic dogs after 2 hours of circulatory arrest below 6 degrees C. J Trauma. 2003;54:S177–S182. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000064516.52295.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Nozari A, Safar P, Wu X, Stezoski WS, Henchir J, Kochanek P, Klain M, Radovsky A, Tisherman SA. Suspended animation can allow survival without brain damage after traumatic exsanguination cardiac arrest of 60 minutes in dogs. J Trauma. 2004;57:1266–1275. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000124268.24159.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Sekaran P, Ehrlich MP, Hagl C, Leavitt ML, Jacobs R, McCullough JN, Bennett-Guerrero E. A comparison of complete blood replacement with varying hematocrit levels on neurological recovery in a porcine model of profound hypothermic (<5 degrees C) circulatory arrest. Anesth Analg. 2001;92:329–334. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200102000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Boulant JA. Role of the preoptic anterior hypothalamus in thermoregulation and fever. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31(Suppl 5):S157–S161. doi: 10.1086/317521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Heller HC. Hibernation: neural aspects. Annu Rev Physiol. 1979;41:305–321. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.41.030179.001513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Fox RH, Davies TW, Marsh FP, Urich H. Hypothermia in a young man with an anterior hypothalamic lesion. Lancet. 1970;2:185–188. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(70)92538-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lammens M, Lissoir F, Carton H. Hypothermia in three patients with multiple sclerosis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1989;91:117–121. doi: 10.1016/s0303-8467(89)80031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Rudelli R, Deck JH. Selective traumatic infarction of the human anterior hypothalamus. Clinical anatomical correlation. J Neurosurg. 1979;50:645–654. doi: 10.3171/jns.1979.50.5.0645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Sullivan F, Hutchinson M, Bahandeka S, Moore RE. Chronic hypothermia in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1987;50:813–815. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.50.6.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].White KD, Scoones DJ, Newman PK. Hypothermia in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1996;61:369–375. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.61.4.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Griffiths AP, Henderson M, Penn ND, Tindall H. Haematological, neurological and psychiatric complications of chronic hypothermia following surgery for craniopharyngioma. Postgrad Med J. 1988;64:617–620. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.64.754.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].He Z, Yamawaki T, Yang S, Day AL, Simpkins JW, Naritomi H. Experimental model of small deep infarcts involving the hypothalamus in rats: changes in body temperature and postural reflex. Stroke. 1999;30:2743–2751. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.12.2743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Luecke RH, Gray EW, South FE. Simulation of passive thermal behavior of a cooling biological system: entry into hibernation. Pflugers Arch. 1971;327:37–52. doi: 10.1007/BF00634097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kleiber M. Body size and metabolism. J Agric Sci. 1932;11:6. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Geiser F, Ruf T. Hibernation versus daily torpor in mammals and birds-physiological variables and classification of torpor patterns. Physiological Zoology. 1995;68:935–966. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Aw TY, Jones DP. Secondary bioenergetic hypoxia. Inhibition of sulfation and glucuronidation reactions in isolated hepatocytes at low O2 concentration. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:8997–9004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Hochachka PW, Buck LT, Doll CJ, Land SC. Unifying theory of hypoxia tolerance: molecular/metabolic defense and rescue mechanisms for surviving oxygen lack. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:9493–9498. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Rolfe DF, Brown GC. Cellular energy utilization and molecular origin of standard metabolic rate in mammals. Physiol Rev. 1997;77:731–758. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.3.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Gautier H, Bonora M, M'Barek SB, Sinclair JD. Effects of hypoxia and cold acclimation on thermoregulation in the rat. J Appl Physiol. 1985;1991(71):1355–1363. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.71.4.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Hayden P, Lindberg RG. Hypoxia-induced torpor in pocket mice (genus: Perognathus) Comp Biochem Physiol. 1970;33:167–179. doi: 10.1016/0010-406x(70)90492-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Hill JR. The oxygen consumption of new-born and adult mammals. Its dependence on the oxygen tension in the inspired air and on the environmental temperature. J Physiol. 1959;149:346–373. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1959.sp006344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Horstman DH, Banderet LE. Hypoxia-induced metabolic and core temperature changes in the squirrel monkey. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol. 1977;42:273–278. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1977.42.2.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Kottke FJ, Phalen JS. Effect of hypoxia upon temperature regulation of mice, dogs, and man. Am J Physiol. 1948;153:10–15. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1948.153.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Kuhnen G, Wloch B, Wunnenberg W. Effects of acute-hypoxia and or hypercapnia on body temperatures and cold induced thermogenesis in the golden-hamster. Journal of Thermal Biology. 1987;12:103–107. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Giesbrecht GG, Fewell JE, Megirian D, Brant R, Remmers JE. Hypoxia similarly impairs metabolic responses to cutaneous and core cold stimuli in conscious rats. J Appl Physiol. 1985;1994(77):726–730. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.77.2.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Barnas GM, Rautenberg W. Shivering and cardiorespiratory responses during normocapnic hypoxia in the pigeon. J Appl Physiol. 1985;1990(68):84–87. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1990.68.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Gleeson M, Barnas GM, Rautenberg W. The effects of hypoxia on the metabolic and cardiorespiratory responses to shivering produced by external and central cooling in the pigeon. Pflugers Arch. 1986;407:312–319. doi: 10.1007/BF00585308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Hemingway A, Nahas GG. Effect of varying degrees of hypoxia on temperature regulation. Am J Physiol. 1952;170:426–433. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1952.170.2.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Mortola JP, Merazzi D, Naso L. Blood flow to the brown adipose tissue of conscious young rabbits during hypoxia in cold and warm conditions. Pflugers Arch. 1999;437:255–260. doi: 10.1007/s004240050777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Madden CJ, Morrison SF. Hypoxic activation of arterial chemoreceptors inhibits sympathetic outflow to brown adipose tissue in rats. J Physiol. 2005;566:559–573. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.086322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Brown adipose tissue: function and physiological significance. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:277–359. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Hsieh AC, Carlson LD. Role of adrenaline and noradrenaline in chemical regulation of heat production. Am J Physiol. 1957;190:243–246. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1957.190.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Beaudry JL, McClelland GB. Thermogenesis in CD-1 mice after combined chronic hypoxia and cold acclimation. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;157:301–309. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Martinez D, Fiori CZ, Baronio D, Carissimi A, Kaminski RS, Kim LJ, Rosa DP, Bos A. Brown adipose tissue: is it affected by intermittent hypoxia? Lipids Health Dis. 2010;9:121. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-9-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Mortola JP, Naso L. Thermogenesis in newborn rats after prenatal or postnatal hypoxia. J Appl Physiol. 1985;1998(85):84–90. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Mortola JP, Feher C. Hypoxia inhibits cold-induced huddling in rat pups. Respir Physiol. 1998;113:213–222. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(98)00056-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Dupre RK, Owen TL. Behavioral thermoregulation by hypoxic rats. J Exp Zool. 1992;262:230–235. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402620213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Prabhakar NR. Oxygen sensing by the carotid body chemoreceptors. J Appl Physiol. 1985;2000(88):2287–2295. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.6.2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Steiner AA, Branco LG. Hypoxia-induced anapyrexia: implications and putative mediators. Annu Rev Physiol. 2002;64:263–288. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.081501.155856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Dawe AR, Spurrier WA. Hibernation induced in ground squirrels by blood transfusion. Science. 1969;163:298–299. doi: 10.1126/science.163.3864.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Dawe AR, Spurrier WA, Armour JA. Summer hibernation induced by cryogenically preserved blood “trigger”. Science. 1970;168:497–498. doi: 10.1126/science.168.3930.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Zhang F, Wang S, Luo Y, Ji X, Nemoto EM, Chen J. When hypothermia meets hypotension and hyperglycemia: the diverse effects of adenosine 5'-monophosphate on cerebral ischemia in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:1022–1034. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Aslami H, Heinen A, Roelofs JJ, Zuurbier CJ, Schultz MJ, Juffermans NP. Suspended animation inducer hydrogen sulfide is protective in an in vivo model of ventilator-induced lung injury. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:1946–1952. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-2022-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Blackstone E, Roth MB. Suspended animation-like state protects mice from lethal hypoxia. Shock. 2007;27:370–372. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31802e27a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Bos EM, Leuvenink HG, Snijder PM, Kloosterhuis NJ, Hillebrands JL, Leemans JC, Florquin S, van Goor H. Hydrogen sulfide-induced hypometabolism prevents renal ischemia/ reperfusion injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:1901–1905. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008121269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Haouzi P, Notet V, Chenuel B, Chalon B, Sponne I, Ogier V, Bihain B. H2S induced hypometabolism in mice is missing in sedated sheep. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2008;160:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Volpato GP, Searles R, Yu B, Scherrer-Crosbie M, Bloch KD, Ichinose F, Zapol WM. Inhaled hydrogen sulfide: a rapidly reversible inhibitor of cardiac and metabolic function in the mouse. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:659–668. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318167af0d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Drabek T, Kochanek PM, Stezoski J, Wu X, Bayir H, Morhard RC, Stezoski SW, Tisherman SA. Intravenous hydrogen sulfide does not induce hypothermia or improve survival from hemorrhagic shock in pigs. Shock. 2011;35:67–73. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181e86f49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Li J, Zhang G, Cai S, Redington AN. Effect of inhaled hydrogen sulfide on metabolic responses in anesthetized, paralyzed, and mechanically ventilated piglets. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2008;9:110–112. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000298639.08519.0C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Osipov RM, Robich MP, Feng J, Liu Y, Clements RT, Glazer HP, Sodha NR, Szabo C, Bianchi C, Sellke FW. Effect of hydrogen sulfide in a porcine model of myocardial ischemia-reperfusion: comparison of different administration regimens and characterization of the cellular mechanisms of protection. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2009;54:287–297. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181b2b72b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Sodha NR, Clements RT, Feng J, Liu Y, Bianchi C, Horvath EM, Szabo C, Stahl GL, Sellke FW. Hydrogen sulfide therapy attenuates the inflammatory response in a porcine model of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;138:977–984. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.08.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Haouzi P, Bell HJ, Notet V, Bihain B. Comparison of the metabolic and ventilatory response to hypoxia and H2S in unsedated mice and rats. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2009;167:316–322. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Beauchamp RO, Jr, Bus JS, Popp JA, Boreiko CJ, Andjelkovich DA. A critical review of the literature on hydrogen sulfide toxicity. Crit Rev Toxicol. 1984;13:25–97. doi: 10.3109/10408448409029321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Cuevasanta E, Denicola A, Alvarez B, Moller MN. Solubility and permeation of hydrogen sulfide in lipid membranes. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34562. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Peng YJ, Nanduri J, Raghuraman G, Souvannakitti D, Gadalla MM, Kumar GK, Snyder SH, Prabhakar NR. H2S mediates O2 sensing in the carotid body. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:10719–10724. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005866107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Li Q, Sun B, Wang X, Jin Z, Zhou Y, Dong L, Jiang LH, Rong W. A crucial role for hydrogen sulfide in oxygen sensing via modulating large conductance calcium-activated potassium channels. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;12:1179–1189. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Daniels IS, Zhang J, O'Brien WG, III, Tao Z, Miki T, Zhao Z, Blackburn MR, Lee CC. A role of erythrocytes in adenosine monophosphate initiation of hypometabolism in mammals. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:20716–20723. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.090845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Lee CC. Is human hibernation possible? Annu Rev Med. 2008;591:177–186. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.59.061506.110403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Swoap SJ, Rathvon M, Gutilla M. AMP does not induce torpor. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;293:R468–R473. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00888.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Mathews WB, Nakamoto Y, Abraham EH, Scheffel U, Hilton J, Ravert HT, Tatsumi M, Rauseo PA, Traughber BJ, Salikhova AY, Dannals RF, Wahl RL. Synthesis and biodistribution of [11C] adenosine 5'-monophosphate ([11C]AMP) Mol Imaging Biol. 2005;7:203–208. doi: 10.1007/s11307-005-4118-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Muzzi M, Blasi F, Masi A, Coppi E, Traini C, Felici R, Pittelli M, Cavone L, Pugliese AM, Moroni F, Chiarugi A. Neurological basis of AMP-dependent thermoregulation and its relevance to central and peripheral hyperthermia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:183–190. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Tupone D, Madden CJ, Morrison SF. Highlights in basic autonomic neurosciences: central adenosine A1 receptor-the key to a hypometabolic state and therapeutic hypothermia? Auton Neurosci. 2013;176:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Jinka TR, Toien O, Drew KL. Season primes the brain in an arctic hibernator to facilitate entrance into torpor mediated by adenosine A(1) receptors. J Neurosci. 2011;31:10752–10758. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1240-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Tupone D, Madden CJ, Morrison SF. Central activation of the A1 adenosine receptor (A1AR) induces a hypothermic, torpor-like state in the rat. J Neurosci. 2013;33:14512–14525. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1980-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Olson JM, Jinka TR, Larson LK, Danielson JJ, Moore JT, Carpluck J, Drew KL. Circannual rhythm in body temperature, torpor, and sensitivity to A(1) adenosine receptor agonist in arctic ground squirrels. J Biol Rhythms. 2013;28:201–207. doi: 10.1177/0748730413490667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Braulke LJ, Klingenspor M, DeBarber A, Tobias SC, Grandy DK, Scanlan TS, Heldmaier G. 3-Iodothyronamine: a novel hormone controlling the balance between glucose and lipid utilisation. J Comp Physiol B. 2008;178:167–177. doi: 10.1007/s00360-007-0208-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Doyle KP, Suchland KL, Ciesielski TM, Lessov NS, Grandy DK, Scanlan TS, Stenzel-Poore MP. Novel thyroxine derivatives, thyronamine and 3-iodothyronamine, induce transient hypothermia and marked neuroprotection against stroke injury. Stroke. 2007;38:2569–2576. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.480277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Hart ME, Suchland KL, Miyakawa M, Bunzow JR, Grandy DK, Scanlan TS. Trace amine-associated receptor agonists: synthesis and evaluation of thyronamines and related analogues. J Med Chem. 2006;49:1101–1112. doi: 10.1021/jm0505718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Panas HN, Lynch LJ, Vallender EJ, Xie Z, Chen GL, Lynn SK, Scanlan TS, Miller GM. Normal thermoregulatory responses to 3-iodothyronamine, trace amines and amphetamine-like psychostimulants in trace amine associated receptor 1 knockout mice. J Neurosci Res. 2010;88:1962–1969. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Petit L, Buu-Ho NP. A synthesis of thyronamine and its lower homolog. J Org Chem. 1961;26:3832–3834. [Google Scholar]

- [90].Chiellini G, Frascarelli S, Ghelardoni S, Carnicelli V, Tobias SC, DeBarber A, Brogioni S, Ronca-Testoni S, Cerbai E, Grandy DK, Scanlan TS, Zucchi R. Cardiac effects of 3-iodothyronamine: a new aminergic system modulating cardiac function. FASEB J. 2007;21:1597–1608. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7474com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Myers JA, Millikan KW, Saclarides TJ. 2nd ed. New York: Springer; 2008. Common surgical diseases: An algorithmic approach to problem solving. [Google Scholar]

- [92].Selzer A, Sudrann RB. Reliability of the determination of cardiac output in man by means of the Fick principle. Circ Res. 1958;6:485–490. doi: 10.1161/01.res.6.4.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Dark J, Miller DR, Licht P, Zucker I. Glucoprivation counteracts effects of testosterone on daily torpor in Siberian hamsters. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:R398–R403. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.270.2.R398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Stamper JL, Dark J. Metabolic fuel availability influences thermoregulation in deer mice (Peromyscus maniculatus) Physiol Behav. 1997;61:521–524. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(96)00495-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Walton JB, Andrews JF. Torpor Induced by Food-Deprivation in the Wood Mouse Apodemus-Sylvaticus. Journal of Zoology. 1981;194:260–263. [Google Scholar]

- [96].Mrosovsky N, Barnes DS. Anorexia, food deprivation and hibernation. Physiol Behav. 1974;12:265–270. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(74)90181-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Oeltgen PR, Bergmann LC, Spurrier WA, Jones SB. Isolation of a hibernation inducing trigger(s) from the plasma of hibernating woodchucks. Prep Biochem. 1978;8:171–188. doi: 10.1080/00327487808069058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Oeltgen PR, Nilekani SP, Nuchols PA, Spurrier WA, Su TP. Further studies on opioids and hibernation: delta opioid receptor ligand selectively induced hibernation in summer-active ground squirrels. Life Sci. 1988;43:1565–1574. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(88)90406-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Bruce DS, Bailey EC, Setran DP, Tramell MS, Jacobson D, Oeltgen PR, Horton ND, Hellgren EC. Circannual variations in bear plasma albumin and its opioid-like effects on guinea pig ileum. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1996;53:885–889. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(95)02153-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Bruce DS, Cope GW, Elam TR, Ruit KA, Oeltgen PR, Su TP. Opioids and hibernation I. Effects of naloxone on bear HIT'S depression of guinea pig ileum contractility and on induction of summer hibernation in the ground squirrel. Life Sci. 1987;41:2107–2113. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(87)90528-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Margules DL, Goldman B, Finck A. Hibernation: an opioiddependent state? Brain Res Bull. 1979;4:721–724. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(79)90003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]