Abstract

Reducing HIV-related stigma may enhance the quality of HIV prevention and care services and is a national prevention goal. The objective of this systematic review was to identify studies of HIV-related stigma among healthcare providers. For studies published between 2010 and 2017, we: (1) searched databases using our keywords, (2) excluded nonpeer reviewed studies, (3) limited the findings to the provider perspective and studies conducted in the United States, (4) extracted and summarized the data, and (5) conducted a contextual review to identify common themes. Of 619 studies retrieved, 6 were included, with 3 themes identified: (1) attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors (n = 6), (2) quality of patient care (n = 3), and (3) education and training (n = 2). Factors associated with HIV-related stigma varied by gender, race, provider category, and clinical setting. Providers with limited recent HIV-stigma training were more likely to exhibit stigmatizing behaviors toward patients. Developing provider-centered stigma-reduction interventions may help advance national HIV prevention and care goals.

Keywords: HIV-related stigma, HIV-related discrimination, healthcare providers, persons living with HIV, persons at risk for HIV

Introduction

More than three decades have passed since HIV was identified in the United States, and more than 1.2 million people in the United States are living with HIV infection.1 Although surveillance data show an annual decline in HIV diagnoses from 2010 to 2014, more than 39,000 new cases of HIV are diagnosed each year in the United States.2 Advances in antiretroviral therapies have prolonged the lives of persons living with HIV (PLWH) and reduced their chances of transmitting HIV to their sexual partners. For persons at high risk for HIV and PLWH, the development of biomedical preventive therapies such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), treatment as prevention, and other evidence-based interventions have decreased their likeli-hood of acquiring or transmitting the disease.3 Despite this progress in public health innovations to address the spread of HIV, factors that prevent or limit patients’ access to HIV services remain.

National strategies to prevent new HIV infections and ensure that PLWH are linked to and retained in care have identified HIV-related stigma as a primary barrier to seeking HIV services.4 Patients seeking preventive services and PLWH seeking treatment services have encountered HIV-related stigma from healthcare providers in both traditional (clinical) and nontraditional (community-based) settings. The experience of HIV-related stigma has been associated with decreased HIV testing, condom use, PrEP uptake, medication adherence, linkage to care, and retention in care, which are all essential components of the HIV care continuum.5 Although patients’ perspectives of HIV-related stigma have been studied,6–8 evidence regarding providers’ perspectives is limited.9

National HIV screening recommendations place healthcare providers at the helm in the fight against HIV. Healthcare providers lead patients through the HIV care continuum with the goal of ensuring high quality prevention and care and reduced morbidity and mortality for patients. However, stigmatizing attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors toward vulnerable populations and PLWH can impede progress in identifying undiagnosed persons with HIV, linking patients to quality care, prescribing HIV treatment, and increasing the number of PLWH who are virally suppressed.7 Research on this topic could inform the development of interventions to reduce HIV-related stigma as a barrier to care. Therefore, the purpose of this systematic review was to examine HIV-related stigma by healthcare providers in the United States, to inform the development of stigma-reduction interventions for healthcare providers.

Materials and Methods

Studies were identified through a systematic search of PubMed, PsycINFO, OVID/Medline, and ProQuest. We searched for studies that focused on HIV and healthcare providers, published between January 2010 and July 2017. The following standardized search terms were used across all databases: “HIV,” “HIV-related stigma,” “stigma,” “social stigma,” “discrimination,” “social discrimination,” “health personnel,” and “healthcare providers.” Duplicate search results were removed, and unpublished dissertations, editorials, commentaries, and studies conducted outside of the United States were excluded from the review. We reviewed titles and abstracts of the search results to determine if the articles addressed the provider perspective of HIV-related stigma. Then, we limited the results to the following key words: (1) HIV, (2) stigma, (3) discrimination, and (4) healthcare providers. A full-text review was conducted on published quantitative and qualitative research studies that met the a priori inclusion criteria. Two trained reviewers (A.G. and A.R.H.) independently abstracted information from eligible studies. Each of the reviewers summarized these data in a table that highlighted the author names, year, location, study design, sample size, demographics, age, and major findings (Table 1).

Table 1.

Systematic Review Findings of Social and Structural Barriers and Facilitators Contributing to HIV-Related Stigma Among Healthcare Providers

| First author | Study designa | Location | Sample size |

Healthcare setting | Health provider category (%) | Social and system level barriers and facilitators of provider HIV-related stigma |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belenko et al.9 | Primary, survey data collection | National, United States | 218 | Jails and prisons | Correctional administration (16%) Correctional security staff (4%) Medical staff (42%) Substance abuse counseling staff (11%) Community-based organization HIV service providers (15%) Other (12%) |

Attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors

|

| Davtyan et al.10 | Primary, qualitative semistructured interviews | Western, United States | 27 | University-based Healthcare Center | Physicians (63%) Nurses (33%) Medical assistant (4%) |

Attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors

|

| Fredericksen et al.11 | Primary, mixed methods | National, United States | 74 | HIV Clinics | Attending physicians (77%) Fellows (14%) Nurses (7%) Other (8%) |

Attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors

|

| Stringer et al.12 | Primary, survey data collection | Southeastern, United States | 651 | Urban Health Centers, Primary Care Clinics, HIV/STI Clinics | Clinicians and clinical support staff (39%) Social/community workers (31%) Administrative staff (21%) Other (8%) Unreported (1%) |

Attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors

|

| Varas-Diaz et al.13 | Primary, mixed methods | Puerto Rico | Stage I = 80 Stage II = 421 | Public health institutions, community based organizations, and academic programs | Stage I: Health professionals (50%), Health professionals in training (50%); Stage II: Health professionals in training (100%) | Attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors

|

| Walcott et al.14 | Primary, qualitative interviews and focus groups | Southern, United States | 14 | HIV clinics and residential facilities | Directors; Social workers; Managers; Chaplain; HIV peer educators (23%) | Attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors

|

Primary refers to primary data collection.

PLWH, persons living with HIV.

Results

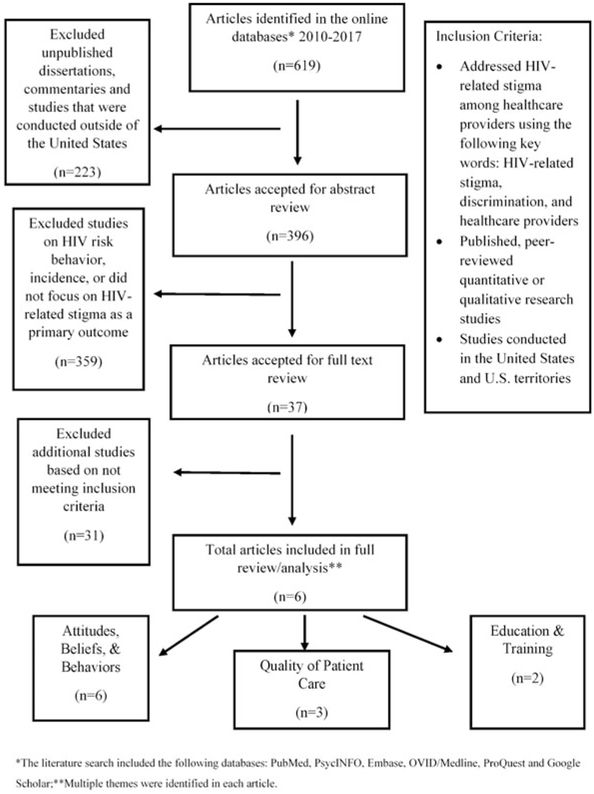

Results from the systematic review are presented (Fig. 1). Six of 619 articles, unique to provider perspectives of HIV-related stigma, met the inclusion criteria and were included in the final review. Study sample sizes ranged from 14 to 651 providers. The studies were located across the United States and Puerto Rico. Healthcare settings for the articles included HIV clinics, healthcare centers, correctional facilities, community based organizations, and primary care clinics. Three overarching themes were identified related to HIV-related stigma by healthcare providers: (1) attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors, (2) quality of patient care, and (3) education and training.

FIG. 1.

Selection process for systematic review of the literature, HIV-related stigma, and healthcare providers, 2010–2017.

Attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors

Six articles discussed provider attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors associated with HIV-related stigma, including homophobia, transphobia, and racism.9–14 The frequency of HIV-related stigma among providers varied by setting and provider category. In three studies, researchers identified at least one stigmatizing attitude toward PLWH or persons at risk for HIV.10–12 Factors associated with stigmatizing behaviors, attitudes, or beliefs varied by gender, race, religion, provider category (e.g., nurses, nurse practitioners, and primary care physicians), and clinical setting9–14 and were primarily among white, male, primary care physicians and providers with limited or no HIV-stigma training in the past 12 months.10–12 Some findings suggest that patients are often stigmatized as being poor, having a high number of sexual partners in their lifetime,10 and frequently engaging in other risky sexual behavior.10,14 Providers also believed that these stigmatizing beliefs and behaviors were based on historically negative portrayals of persons at risk for HIV, PLWH,10 and persons who seek HIV prevention and care services.14 HIV-related stigma exhibited by providers was less likely among those who worked in settings where policies focused on HIV-related stigma were reinforced.12

Quality of patient care

Three studies examined how provider stigma toward PLWH or persons at risk for HIV could affect patient care.10–12 Provider fear of acquiring HIV through occupational exposure led to reduced quality of care, refusal of care, and anxiety when providing services to PLWH.10 This fear was higher among providers with limited awareness of or access to post-exposure prophylaxis within their healthcare setting or clinic.12 Moreover, patient–provider discordance in the prioritization of addressing HIV-related stigma over other healthcare needs led to reduced quality of care or patient satisfaction.11

Education and training

Two articles examined education and training of health professionals.10,12 Davtyan et al.10 identified that limited opportunities for clinical education and practice for non-HIV specialty doctors facilitated provider HIV-related stigma. Stringer et al.12 found lower rates of stigmatizing attitudes among healthcare providers who received HIV stigma training in the past 12 months.

Discussion

Reducing HIV-related stigma to combat new HIV infections and increase linkage and retention is a national HIV prevention goal.4 We identified six articles that assessed social and structural factors contributing to HIV-related stigma from the healthcare provider perspective. Three overarching themes contributed to, or were affected by, HIV-related stigma by healthcare providers: (1) attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors, (2) quality of patient care, and (3) education and training.

This review is unique, because it summarizes literature with a focus solely on healthcare providers. Another recently published review included mostly articles that assessed patients’ perspectives of healthcare providers and HIV-related stigma.8 The small sample of studies underscores the need for more research from the healthcare provider perspective to help inform prevention interventions. These findings also suggest a relationship between stigma by healthcare providers and diminished quality of care, factors that could hinder progress in reaching national HIV prevention goals.

Our review showed that stigma can be manifested through inadvertent behaviors and ideologies, such as homophobia, transphobia, racism, and negative views of persons who inject drugs, and can create uncomfortable environments and act as a barrier to HIV prevention, treatment, and care.10,14 Less stigmatizing attitudes by providers7 can help to reduce social and structural barriers to HIV care across the continuum. Interventions that increase introspection, cultural awareness, and sensitivity of providers can help decrease biases and support improved care outcomes for PLWH and people at risk of HIV infection.15,16 Online assessments, such as the Teach Tolerance survey, “Test Yourself for Hidden Bias,”17 allow providers to privately examine themselves for implicit biases and then begin the process of understanding their personal context even as they try to improve as providers. In addition, hiring a diversified workforce, reorganizing the staff structure to effectively meet the needs of the care setting, and training for providers help to facilitate care approaches that are comprehensive and sensitive to a broad range of people.18

Policies, like opt-out testing, help to reduce stigma by normalizing HIV testing and by removing risk-based screening practices; this can help to positively impact public health by reducing testing barriers and increasing the numbers of persons who are routinely tested for HIV infection.10 However, even with universal HIV testing strategies, stigma-based challenges to HIV testing and care often remain, due to concerns with negative treatment by some providers and office staff and privacy and confidentiality concerns. Healthcare providers have an “ethical obligation to provide optimum confidential care to all individuals without judgment about their gender identity, sexual orientation, or life choices and behaviors,”19 but too often that obligation does not translate to the direct patient care setting. If we are to successfully reach national HIV prevention goals, reducing stigma (real and perceived by patients) by healthcare providers is vital.

There may also be lessons to be learned directly from patients who present for HIV care. In some clinical settings, offering patients the opportunity to provide feedback not only helps patients feel heard and supported but also provides healthcare providers and administrators with quality improvement data that can constructively inform processes and strengthen patient care.20 Using innovative strategies to identify and collect feedback from patients who are not in clinical HIV care (e.g., participants of community-based programs that actively engage PLWH and persons who are vulnerable for HIV) could also be very informative. These innovations should be based on collective and timely data from patients and new trainings implemented and designed by public health professionals, health educators, and other health providers. Moreover, policies and procedures, collaboratively developed by healthcare providers, public health professionals, and legislators, should be implemented. Once found to be effective, these new trainings, policies, and procedures for providers could potentially increase access to HIV care and services and improve the initiation and adherence to behavioral and biomedical interventions among patients.8

HIV-related stigma continues to be a prevalent issue for PLWH and people who are vulnerable for HIV. Their encounters with HIV-related stigma range from providers who take extreme precautionary measures during routine examinations to use of stigmatizing language, to denial of services and treatment.11 Better understanding of the ways in which healthcare provider stigma may influence HIV care can inform prevention interventions and polices in various healthcare settings.14 Understanding and addressing healthcare provider stigma will potentially have an effect on HIV engagement and care by allowing patients to feel more supported during their HIV diagnoses and lifetime of HIV-related medical interactions.

Given the disproportionate burden of HIV-related stigma in the United States, the development of interventions21 that decrease healthcare provider stigma, increase healthcare provider awareness of stigma, and establish the presence of clinical policies to address HIV-related stigma are warranted. These efforts would bring us closer to reaching national HIV prevention goals to reduce stigma and establish competent and responsive HIV treatment and care.4

Limitations

This review has limitations. First, three of six (50%) studies included small sample sizes (n < 100 persons); larger samples of providers will be needed for future studies to provide more robust analyses and may be more generalizable. Second, social desirability and personal bias may have played a role in provider responses. The use of computer-assisted quantitative surveys may offer additional privacy and decrease this type of bias. Third, factors such as geographic location (cosmopolitan vs. insular) may play a role in the perspective of healthcare providers and access to care for HIV-positive patients, especially those who reside in the southern United States, an area in which the context of institutionalized racism and discrimination may create additional barriers to care. When developing surveys and measuring HIV disparities, particularly when addressing disparities among populations who have experienced ongoing marginalization (e.g., African Americans, Hispanics/Latinos, and other persons of color, especially those who reside in the Southern United States), it is essential to acknowledge and measure the effects of racism and discrimination and how those factors could impact their risk for HIV and utilization of HIV prevention, treatment, and care services. This context should be considered, and potential biases accounted for, as surveys are being developed and implemented with providers in the United States. Fourth, the authors only assessed peer-reviewed articles published in the last 8 years. This time frame was chosen in an effort to isolate more recent healthcare provider studies relating to biomedical interventions such as PrEP and to assess more up-to-date literature. Finally, the data are limited to studies conducted in the United States and do not include lessons learned from countries with limited resources, yet innovative approaches to addressing HIV-related stigma were exhibited by healthcare providers.22

Footnotes

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV surveillance report, 2016. 2017. Available at: www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html (Last accessed February 27, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnosed HIV infection among adults and adolescents in metropolitan statistical areas—United States and Puerto Rico, 2015. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report 2017;22. Available at: www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/surveillance (Last accessed March 3, 2018).

- 3.Smith DK, Van Handel M, Huggin R. Estimated coverage to address financial barriers to HIV preexposure prophylaxis among persons with indications for its use, United States, 2016. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017;76:465–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Office of National AIDS Policy. National HIV/AIDS strategy for the United States: Updated to 2020. 2015. Washington, DC: Available at: https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/national-hiv-aids-strategy/nhas-update (Last accessed March 3, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Understanding the HIV care continuum. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/dhap_continuum.pdf (Last accessed March 3, 2018).

- 6.Turan B, Budhwani H, Fazeli PL, et al. How does stigma affect people living with HIV? The mediating roles of internalized and anticipated HIV stigma in the effects of perceived community stigma on health and psychosocial outcomes. AIDS Behav 2017;21:283–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eaton LA, Driffin DD, Kegler C, et al. The role of stigma and medical mistrust in the routine healthcare engagement of black men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health 2015;105:75–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marshall A, Brewington S, Kathryn A, Haynes T, Zaller N. Measuring HIV-related stigma among healthcare providers: A systematic review. AIDS Care 2017;29:1337–1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belenko S, Dembo R, Copenhaver M, et al. HIV stigma in prisons and jails: Results from a staff survey. AIDS Behav 2016;20:71–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davtyan M, Olshansky EF, Brown B, Lakon C. A grounded theory study of HIV-related stigma in U.S.-based healthcare settings. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 2017;28:907–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fredericksen R, Edwards T, Crane HM, et al. Patient and provider priorities of self-reported domains in HIV clinical care. AIDS Care 2015;27:1255–1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stringer KL, Turan B, McCormick L, et al. HIV-related stigma among healthcare providers in the Deep South. AIDS Behav 2016;20:115–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Varas-Diaz N, Neilands T, Rivera S, Betancourt E. Religion and HIV/AIDS stigma, Implications for health professionals in Puerto Rico. Glob Public Health 2010;5:295–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walcott M, Kempf MC, Merlin JS, Turan JM. Structural community factors and sub-optimal engagement in HIV care among low-income women in the Deep South of the USA. Cult Health Sex 2016;18:682–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ford OG. How to reverse implicit bias in HIV care: 6 steps to take today. Available at: www.thebodypro.com/content/80491/how-to-reverse-implicit-bias-in-hiv-care-6-steps-t.html?getPage=4 (Last accessed August 17, 2018).

- 16.Institute of Medicine. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2003. Available at: 10.17226/10260 (Last accessed April 6, 2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teaching Tolerance. Test Yourself for Hidden Bias. Available at: https://www.tolerance.org/professional-development/test-yourself-for-hidden-bias (Last accessed January 30, 2018).

- 18.UNAIDS. Agenda for zero discrimination in health-care settings. 2017. Available at: www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2017ZeroDiscriminationHealthCare.pdf (Last accessed March 3, 2018).

- 19.HIV: Science and stigma. Lancet 2014;384:207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnston S, Kendall C, Hogel M, McLaren M, Liddy C. Measures of quality of care for people with HIV: A scoping review of performance indicators for primary care. PLoS One 2015;10:e0136757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Batey DS, Whitifield S, Mulla M, et al. Adaptation and implementation of an intervention to reduce HIV-related stigma among healthcare workers in the United States: Piloting of the FRESH workshop. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2016;30:519–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aggarwal S, Lee DH, Minteer WB, et al. Another generation of stigma? Assessing healthcare student perceptions of HIV-positive patients in Mwanza, Tanzania. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2017;31:87–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]