Abstract

Objective:

Bipolar disorder (BPD) is a highly morbid disorder increasingly recognized in adolescents. The aim of this study was to examine the risk for substance use disorders (SUDs; alcohol or drug use or dependence) and cigarette smoking in adolescents with BPD.

Methods:

We evaluated the risk for SUDs and cigarette smoking in a case control family-based study of adolescents with (n=105, age 13.6 ± 2.5 years) and without (“controls”, n=98, age 13.7 ± 2.1 years) BPD at baseline and at 5 year follow-up (BPD: n=68; controls: n=81; 73% re-ascertainment). Rates of disorders were assessed by blinded structured interviews.

Results:

Adolescents growing up with BPD, compared to controls, were more likely to endorse higher rates of SUD (51% vs. 26%; Hazard Ratio (HR) =2.1; 95% Confidence Interval (CI): 1.2, 3.8, p=0.001) and cigarette smoking (51% vs. 17%; HR = 3.2; 95% CI: 1.6, 6.7; p=0.001); as well as earlier-onset of SUD (SUD (14.9 ± 2.6[SD] years vs. 16.5 ± 1.6 years; t=2.6; p=0.01). Subjects with the persistence of a BPD diagnosis were also more likely to endorse cigarette smoking and SUD in comparison to those who lost a BPD diagnosis or controls at follow-up.

Conclusion:

The results provide further evidence that adolescents with BPD are at a significantly increased risk to develop cigarette smoking and SUDs when compared to their non-mood disordered peers. These findings indicate that youth with BPD should be carefully monitored for the development of cigarette smoking and SUDs.

Keywords: adolescent, family, bipolar disorder, substance abuse, longitudinal

Introduction

A growing literature documents that juvenile bipolar disorder (BPD) is a prevalent, highly morbid condition estimated to affect up to 5% of adolescents1, 2. Longitudinal studies document that the disorder is associated with elevated levels of functional impairments including high rates of psychiatric hospitalization, academic and occupational underachievement, disruption of the family environment, psychosocial disability and comorbid psychiatric disorders3–6.

Among the most concerning problems in BPD are those associated with the development of cigarette smoking and substance use disorders (SUDs; drug or alcohol abuse or dependence)7. For instance, about one-half of referred and community samples of adults with BPD have a lifetime history of SUDs2 and excess BPD has been reported in SUD 8, 9. Data suggest a heightened risk for SUDs in adults who experienced BPD onset prior to age 18 years7, 10, 11.

The literature also suggests that juvenile BPD is a major risk factor for SUDs12–15 and is over-represented in youth with SUDs15, 16. For example, we previously reported that 31% of adolescents with BPD manifest a SUD at a mean age of 14 years compared to only 4% in a matched group of non-mood disordered adolescents (p< 0.001).12 Since the age of onset of BPD precedes that of SUDs12, 14, 17, it has been suggested the direction of risk is from BPD to SUD12, 14, 17.

The current study’s main aim was to examine the association between BPD and SUD in developing adolescents. We examined findings from a controlled, five year longitudinal family study of adolescents with and without BPD attending to developmental factors, correlates of BPD, and psychiatric comorbidity. We hypothesized that adolescents with BPD would continue to be at higher risk for SUD than non-mood disordered adolescents, and that the association between BPD and SUD would be independent of psychiatric comorbidity with ADHD and conduct disorder-two conditions known to raise the risk for SUD. Furthermore, we posited that persistence of BPD would be associated with the highest risk for SUD relative to non-persistent cases and controls.

1. Methods

1.1. Subjects

The current analysis is based on the five-year follow-up study, the methods of which are described in detail in the baseline report of this sample 12. We originally ascertained 108 bipolar adolescent probands and 98 non-mood disordered controls. Briefly, at baseline potential subjects were excluded if they had been adopted, if they had major sensorimotor handicaps, autism, inadequate command of the English language, or a Full Scale IQ less than 70. Child assent and parental consent was obtained.

1.2. Assessments

All diagnostic assessments were made using DSM-IV-based semi-structured interviews. Raters were blind to the (re)ascertainment status of the subjects. Psychiatric assessments for adolescents relied on the DSM-IV Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders-Epidemiologic Version (KSADS-E)18 while for subjects 18 or older the Scheduled Clinical Interview Diagnosis (SCID)19 was used. For each diagnosis at baseline and follow-up, information was gathered regarding the ages at onset and offset of syndromatic criteria, interval history (follow-up), and treatment history. As reported previously20, for a subject to be diagnosed with BPD, he or she had to meet full DSM-IV criteria for bipolar I or II disorder by both structured and clinical interviews.

Substance use disorders (SUD) included any non-nicotine drug or alcohol abuse or dependence, and was diagnosed based on DSM-IV criteria. To meet for nicotine dependence, subjects under 18 needed to endorse smoking daily, whereas subjects over 18 needed to endorse smoking at least a pack of cigarettes per day. Rates of disorders reported are lifetime prevalence and SUD data reflect moderate to severe impairment.

All cases at baseline and follow-up were presented to board certified child psychiatrists and licensed psychologists. Diagnoses were considered positive only if the disorder was of clinical concern due to the nature of the symptoms, the associated impairment, and the coherence of the clinical picture. Kappa coefficients of agreement were evaluated by having three experienced, board-certified child and adult psychiatrists diagnose subjects from audio taped interview. Based on 500 assessments from interviews of children and adults, the median kappa coefficient was 0.98 and included kappa coefficients for eight individual diagnoses.

1.3. Statistical analysis

The initial sample included 105 BPD probands and their first-degree relatives and 98 controls and their first-degree relatives 12. For this analysis, we merged the initial and follow-up data and computed lifetime rates of disorders and characteristics using the most severe diagnosis, the earliest onsets and the latest offsets unless noted otherwise. We compared demographic and clinical characteristics between cases and controls using t-tests for continuous outcomes, χ2 tests for binary outcomes and the Wilcoxon Rank sum test for socio-economic status (SES).

The Hollingshead Four-Factor Index was used to assess socioeconomic status (SES). We used Kaplan Meier Curves and Cox proportional hazard models to assess the risk of SUD at follow-up between BPD subjects and control subjects as well as between subjects with persistent BPD and non-persistent BPD. Persistence of BPD was described as full BPD at wave 1 and full or subthreshold BPD criteria at follow-up (persistent BPD)5. Subjects with BPD at baseline who no longer met criteria for BPD at follow-up were considered non-persistent BPD5. The age of onset was computed using the earliest age of onset between baseline and follow-up. An alpha-level of 0.05 was used to assert statistical significance; all statistical tests were two-tailed. We calculated all statistics using Stata 12.021.

2. Results

Among the 203 probands enrolled in the study at wave 1, we had follow-up data on 149 (73%) of probands: 68 BPD subjects and 81 control subjects. More BPD subjects were lost to follow-up compared to controls (37 (35%) vs. 17 (17%), χ2=8.3, p=0.004).

2.1. Clinical characteristics

As shown in Table 1, we found no significant differences at follow-up for age or sex between cases and controls. BPD subjects had a lower SES (higher Hollingshead scores) and more parental history of SUD.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics and lifetime comorbidities of the follow-up sample: Bipolar Disorder and Controls (N=149)

| Controls (n=81) |

BPD (n=68) |

Test statistics, p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |

| Age | 19.2 ± 2.5 | 20.1 ± 3.1 | t=−2.0, p=0.05 |

| Socioeconomic status | 1.9 ± 1.0 | 2.5 ± 1.1 | z=−3.4, p=0.0006 |

| N (%) | N(%) | ||

| Sex (male) | 48 (59) | 42 (62) | χ2 =1.0, p=0.76 |

| Parental History of SUD | 38 (47) | 51 (75) | χ2 =12.1, p<0.001 |

| Comorbidity(ies) | |||

| Multiple Anxiety Disorders | 7 (9) | 22 (32) | χ2=13.3, p<0.001 |

| ADHD | 16 (20) | 52 (76) | χ2 =47.9, p<0.001 |

| Conduct Disorder | 12 (15) | 43 (63) | χ2 =37.2, p<0.001 |

| Oppositional Defiant Disorder | 13 (16) | 63 (93) | χ2 =86.8, p<0.001 |

2.1.1. Disorders Comorbid with BPD

The BPD group at follow-up had higher lifetime rates of comorbid psychiatric disorders compared to controls. Significant differences were noted for conduct, oppositional defiant, ADHD, and multiple anxiety disorders (Table 1).

2.2. SUD and Cigarette Smoking in Youth with BPD

The BPD probands, compared to controls, had more new onset cases of SUD: alcohol abuse (14 (27%) vs. 12 (15%)), alcohol dependence (14 (22%) vs. 4 (5%)), drug abuse (10 (19%) vs. 10 (13%)), drug dependence (13 (24%) vs. 7 (9%)), any SUD (15 (31%) vs. 18 (23%)), and smoking (18 (25%) vs. 11 (14%)).

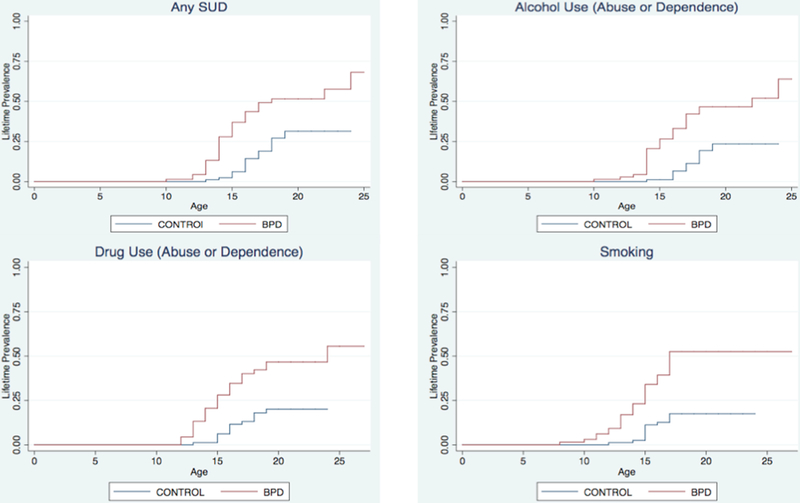

At the five year follow-up, while adjusting for SES and parental history of SUD, probands with BPD, compared to controls, reported a significantly higher rate of lifetime SUD (35 (51%) vs. 21 (26%), Hazard Ratio (HR)=2.1; 95% Confidence Interval (CI): 1.2, 3.8; p=0.001; Figure 1), as well as higher rates of all individual SUD including alcohol abuse (HR: 2.4; 95% CI: 1.2, 4.9; p=0.01), alcohol dependence (HR: 5.0; 95% CI:1.6, 15.7; p=0.006), drug abuse (HR:2.5; 95% CI:1.2, 5.6; p=0.02), drug dependence (HR:3.1; 95% CI:1.3, 7.2; p=0.01) and smoking (HR: 3.2; 95% CI: 1.6, 6.7; p=0.001). Subjects with BPD also had higher rates of an alcohol use disorder (abuse or dependence; HR: 2.6; 95% CI: 1.3, 5.0; p=0.006) and drug use disorder (HR: 2.6; 95% CI: 1.3, 5.1; p=0.007). Likewise, more BPD probands (38%, N=26) had combined alcohol plus drug use disorders (10%, N=8; adjusting for SES and parental history of SUD: HR=4.0; 95% CI: 1.6, 9.6; p=0.001).

Figure 1. Survival Curves for Substance Use and Smoking (N=149).

While adjusting for SES and parental history of SUD, probands with BPD, compared to controls, reported a significantly higher rate of lifetime SUD (35 (51%) vs. 21 (26%), Hazard Ratio (HR) =2.1;95% Confidence Interval (CI):1.2, 3.8; p = 0.001). Subject with BPD also had higher rates of alcohol use disorders (abuse or dependence;HR:2.6; 95% CI:1.3, 5.0; p = 0.006), drug use disorders (HR:2.6; 95% CI: 1.3, 5.1; p = 0.007) and cigarette smoking (smoking (HR:3.2; 95% CI: 1.6, 6.7; p = 0.001).

There was more abuse or dependence of cannabis, opiates, cocaine, sedatives, stimulants, hallucinogens, and other drugs (including aspirin and ecstasy) among subjects with BPD compared to controls (any use disorder, adjusting for SES and parental history of SUD: 27 (40%) vs. 11 (14%); Odds Ratio (OR): 3.7; 95% CI: 1.5, 9.0; p=0.003). While cannabis was the most commonly abused drug, 13% and 9% of the BPD group had an addiction to opiates or cocaine (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Specific Drugs of Abuse and Dependence in Bipolar Disorder and Controls (N=149)

| Controls (n=81) |

BPD (n=68) |

Test statistics, p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Type | N(%) | N(%) | |

| Cannabis | 10 (12) | 24 (35) | χ2=11.1, p=0.001 |

| Opiates | 2 (2) | 9 (13) | χ2=6.3, p=0.01 |

| Cocaine | 1 (1) | 6 (9) | χ2=4.8, p=0.047* |

| Sedatives | 0 (0) | 3 (4) | χ2 =3.6, p=0.09* |

| Stimulants | 0 (0) | 2 (3) | χ2 =2.4, p=0.21* |

| Hallucinogens | 1 (1) | 3 (4) | χ2=1.4, p=0.3* |

| Other (including aspirin and ecstasy) | 0 (0) | 3 (4) | χ2=3.6, p=0.09* |

Exact test was employed

2.2.1. The Effect of Comorbid Disorders on SUD

We repeated our analyses on SUD and nicotine addiction controlling for ADHD and conduct disorder (CD) – two major comorbid disorders found to independently result in SUD 22. When we added ADHD to the model with SES and parental SUD, we found a significant effect of BPD status on age-adjusted risk of nicotine dependence (HR: 3.8; 95% CI: 1.7, 9.0; p=0.002), alcohol dependence (HR: 7.3; 95% CI: 2.1, 25.8; p=0.002), drug abuse (HR: 4.1; 95% CI: 1.7, 10.2; p=0.002), drug dependence (HR: 3.5; 95% CI: 1.4, 9.3; p=0.01), and overall SUD (HR: 2.5; 95% CI: 1.2, 5.0; p=0.01). We did not find a significant association for alcohol abuse (HR:2.1; 95% CI: 1.0, 4.4; p=0.07). When we added conduct disorder to the model with SES and parental SUD, all associations lost significance (all p values > 0.05).

SUD onset in Youth with BPD

The mean age of onset for any SUD was 15.5 ± 2.4 years and was similar for the individual ages of onset for drug use disorders (15.5 ± 2.4 years) and alcohol use disorders (16.0 ± 2.4 years). In general, BPD subjects had a > 1 year earlier-onset of a SUD compared to controls: any SUD (14.9 ± 2.6 years vs. 16.5 ± 1.6 years; t=2.6; p=0.01), alcohol use disorders (15.5 ± 2.7 years vs. 17.1 ± 1.4 years; t=2.2; p=0.03), and any drug use disorders (15.1 ± 2.6 years vs. 16.2 ± 1.6 years; t=1.4; p=0.16). The mean duration of any SUD was 3.4 ± 3.1 years. We found that BPD subjects manifest a longer duration of SUD relative to controls (4.4 ± 3.2 years vs. 1.6 ± 1.9 years; p=0.0007).

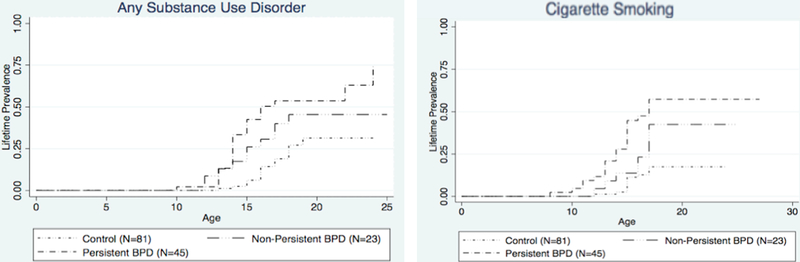

SUD and Nicotine Addiction in BPD at Follow-up: Persistent vs. Non-Persistent BPD

Among the 68 subjects with BPD at both baseline and wave 2 assessments, 23 (34%) reported no BPD at follow-up, 9 (13%) reported subthreshold BPD, and 36 (53%) reported having full-BPD. Qualitative analysis of the data suggested that those with persistent BPD had the highest risk for SUD relative to those with non-persistent BPD and controls. Moreover, we found a linear effect of the three groups (controls = 0, non-persistent BPD = 1, persistent BPD = 2) for any SUD (HR:1.8 (1.3, 2.4), p<0.001), and for smoking (HR: 2.1 (1.5, 2.95), p<0.001.) However, when stratifying solely by the presence or absence of persistent BPD, we failed to find significant differences between persistent BPD (N=45) and non-persistent BPD (N=23) in the percentage of any SUD or cigarette smoking (Figure 2, adjusting for SES and parental history of SUD: Non-persistent vs. controls: HR: 1.6; 95% CI: 0.7, 3.5; p=0.25; Persistent vs. controls: HR: 2.5; 95% CI: 1.3, 4.6; p=0.005; Persistent vs. non-persistent: HR: 1.5; 95% CI: 0.7, 3.2; p=0.25). We found similar results for cigarette smoking (Non-persistent vs. controls: HR: 2.1; 95% CI: 0.9, 5.3; p=0.11; Persistent vs. controls: HR: 4.1; 95% CI: 1.9, 8.9; p<0.001; Persistent vs. non-persistent: HR: 2.0; 95% CI: 0.9, 4.3; p=0.09).

Figure 2. Substance Use and Cigarette Smoking (N=149).

While adjusting for SES and parental history of SUD, we found that those with persistent BPD had the highest risk for SUD and cigarette smoking compared to those with non-persistent BPD and controls (SUD: Non-persisdent vs. controls: HR: 1.6; 95% CI: 0.7, 3.5; p = 0.25; presisdent vs. controls: HR: 2.5; 95% CI: 1.3, 4.6; p = 0.005; presisdent vs. non-persisdent: HR: 1.5; 95% CI: 0.7, 3.2; p = 0.25; Cigarette Smoking: Non-presistent vs. controls: HR: 2.1; 95% CI: 0.9, 5.3; p = 0.11; Persistent vs. controls: HR: 4.1; 95% CI: 1.9, 8.9; p < 0.001; persistent vs. non-persistent: HR: 2.0; 95% CI: 0.9, 4.9; p = 0.09).

BPD Characteristics associated with SUD

To examine what characteristics within BPD are associated with SUD at follow-up, BPD probands with SUD (N=35) were compared to BPD probands without SUD (N=33) (Table 3). BPD subjects with versus without SUD had more lifetime hospitalizations related to psychiatric or SUD (72% (N=49) vs. 4% (N=3); Χ2=76.0, p<0.0001). As expected, there were higher rates of lifetime psychopharmacology in all probands with BPD compared to controls, but these percentages did not significantly differ between those with and without SUD. At baseline or during the 5-year follow-up, we did not find any differences in rates of pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy between BPD subjects with and without SUD (all p values >0.05).

Table 3.

Clinical Characteristics and lifetime comorbidities of Individuals with Bipolar Disorder (BPD) without (−) and with (+) Substance Use Disorders

| BPD-SUD (n=33) |

BPD + SUD (n=35) |

Test statistics, p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |

| Age | 18.7 ± 2.9 | 21.3 ± 2.8 | t=−3.8, p=0.0004 |

| Socioeconomic status (SES) | 2.3 ± 1.0 | 2.7 ± 1.2 | z=−1.5, p=0.14 |

| N (%) | N(%) | ||

| Sex (male), % | 20 (61) | 22 (63) | χ2 =0.04, p=0.85 |

| Parental History of SUD | 24 (73) | 27 (77) | χ2 =0.18, p=0.67 |

| Parental History of MDD | 23 (72) | 30 (86) | χ2 =1.9, p=0.16 |

| Parental History of BPD | 10 (31) | 10 (29) | χ2 =0.06, p=0.81 |

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | ||

| Total BPD Symptom Count | 5.8 ± 1.3 | 6.3 ± 1.2 | t=−1.4, p=0.16 |

| BPD Episodes | 24.8 ± 39.8 | 30.6 ± 48.6 | t=−0.6, p=0.60 |

| N(%) | N(%) | ||

| BPD onset in adolescence | 5 (15) | 9 (26) | χ2=1.2, p=0.3 |

| MDD onset in adolescence | 5 (15) | 11 (31) | χ2 =2.5, p=0.1 |

| Conduct Disorder | 5 (15) | 19 (54) | χ2 =17.0, p<0.001 |

| Oppositional Defiant Disorder | 14 (42) | 23 (66) | χ2 =3.71, p=0.05 |

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | ||

| IQ | 102.4 ± 14.3 | 102.1 ± 11.2 | t=0.09, p=0.92 |

| N(%) | N(%) | ||

| Repeated a Grade | 5 (15) | 10 (292) | χ2 =1.78, p=0.18 |

| Special Class | 22 (67) | 21 (60) | χ2 =0.32, p=0.57 |

| Extra Help | 25 (76) | 27 (77) | χ2 =0.02, p=0.89 |

Abbreviations used: MDD=major depressive disorder

We then examined the temporal relationship of BPD and SUD by examining ages of onset of both disorders. A majority of BPD subjects (N=29 (83%)) experienced the full syndromatic onset of their BPD prior to SUD, while a minority had the onset within the same year (N=3 (9%)) or after the onset of SUD (N=3 (9%)). We did not find a significant difference in the chronology of mania compared to depression in the sample (onset of mania prior to depression in probands with BPD with and without SUD). We also did not find a significant difference in lifetime SUD or cigarette smoking between BPD I and BPD II at baseline (N’s=47, 58, respectively) or follow-up (31, 37; all p values >0.05).

Discussion

The results of this study support our hypotheses that developing adolescents with BPD manifest an increased risk for cigarette smoking and SUDs compared to their non-mood disordered peers. We also found a disturbing trend of more combined and severe SUDs in adolescents with BPD compared to controls. There was a linear trend for risk of cigarette smoking and SUD with persistent > nonpersistent > controls – although both BPD groups continued to be at higher risk than controls. These data punctuate the need for careful monitoring of cigarette smoking and SUD by providers for these highly dysregulated adolescents.

Our findings that adolescent BPD increases the risk for cigarette smoking and SUDs mirror an emerging literature documenting this risk in clinical and epidemiological samples14, 23–26. For instance, Goldstein et al.17 found that in 12–17 year old adolescents with BPD followed for a mean of 2.7 years, 32% of subjects had their first-onset of SUD, with 76% of the aforementioned group manifesting multiple SUDs. Our data also support findings noted in adult-based studies that provide further evidence linking age at onset of BPD with the risk for SUD7, 10, 12, 27–29. For instance, Lin et al.10 reported that early onset BPD was associated with a higher risk for SUD compared to later onset BPD.

Given that early-onset BPD is associated with SUD, and early-onset SUD is associated with a more pernicious SUD course and ongoing impairment30, BPD youth are at a very high risk for severe SUD related difficulties in addition to a chronic BPD course13, 31. In support of this notion, Kozloff and colleagues25 noted that individuals with BPD plus SUD were more likely to use mental health services compared to those without this comorbidity. These data highlight the need for careful ongoing screening of cigarette and substance use in adolescents and young adults 32 with BPD.

An important finding in the current study was that the higher risk of cigarette smoking and SUD in BPD youth was independent of ADHD22. However, unlike our results at baseline, the risk for SUD did not remain significant in our follow-up BPD sample when controlling for CD, suggesting that the comorbidity with CD mediates this risk. These findings may be confounded by the high risk for CD in BPD in our and other’s samples5, 6. Conversely, it may be that CD in BPD is an important variable in linking SUD to BPD33.

While potentially confounded by treatment effects on “persistence” and limited by statistical power, we found evidence of a linear effect in that subjects with persistent BPD manifest the highest risk (and earliest onset) of cigarette smoking and SUD relative to nonpersistent BPD and controls. However, our data also suggest that even subjects with non-persistent BPD were at elevated risk for SUD relative to controls. Our findings are consistent with a five-year follow-up report by Wozniak et al.5 who, using a similar definition of “persistence,” reported an almost two-fold higher risk for SUD and cigarette smoking in persistent cases. Along the same lines, Lewinsohn et al.34 reported a higher risk for alcohol and drug use in those with full BPD versus subthreshold BPD.

Similar to others, we found that the majority of adolescents (83%) with BPD and SUD experienced the full syndromatic onset of their BPD prior to SUD, while a minority had the onset of their BPD after that of SUD 35–37. Winokur et al.38, Strakowski et al.39, 40, and Lin et al.10 have helped elucidate this developmental timing of SUD as it pertains to BPD in adults. Lin et al.10 showed that early onset BPD precedes and is associated with SUD, and Winokur38 reported that a subgroup of subjects with BPD plus SUD showed evidence of alcoholism secondary to BPD. It is possible to hypothesize that BPD- associated poor judgment, limited self-control, and emotional dysregulation and disinhibition contribute to the high risk for SUD in young adulthood32, 41. In support of this notion, we recently reported a strong relationship between the degree of emotional dysregulation and the risk for SUD in BPD32.

The findings in the current study need to be tempered against methodological limitations. The sample was mostly Caucasian and may not generalize to community or minority samples. Although our sample was large, the subgroup of adolescents in the control group and those with specific disorders was relatively small, limiting our statistical power for some analyses. Our assessments at baseline and five year follow-up relied on retrospective reporting to detail BPD, SUD, and other psychiatric comorbidity, and may have missed important interval data. Lastly, SUD was defined categorically by subjects meeting full DSM criteria for abuse or dependence, and not by urine toxicology screens. Using these definitions, use and misuse of substances as well as subthreshold non-BPD psychopathology or substance abuse was not captured. Further studies should integrate parent, subject self-report, and subject report during structured interview, as well as urine toxicology testing to more accurately identify substance misuse both categorically and dimensionally in youth42.

Despite these limitations, the current data adds to a growing literature indicating that pediatric-onset BPD is associated with a highly significant risk for cigarette smoking and early onset SUD. Persistence of the active symptoms of BPD appears related to the risk for cigarette smoking and SUD at follow-up. Since BPD onsets prior to the SUD in the majority of the cases, practitioners following these individuals should treat symptoms of BPD, and continue to carefully monitor for cigarette smoking and the development of SUD.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source:

All phases of this study were supported by an NIH grant RO1 DA12945 and K24 DA016264 to Dr. Timothy Wilens.

Financial Disclosures:

Timothy Wilens: Dr. Timothy Wilens receives or has received grant support from the following sources: NIH(NIDA), and Pfizer. Dr. Timothy Wilens is or has been a consultant for: Euthymics/Neurovance, NIH(NIDA), Theravance and TRIS. Dr. Timothy Wilens has a published book with Guilford Press. Straight Talk About Psychiatric Medications for Kids; and co/edited books ADHD in Children and Adults, and Comprehensive Clinical Psychiatry. Dr. Wilens is Director of the Center for Addiction Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital. He serves as a consultant to the US National Football League (ERM Associates), U.S. Minor/Major League Baseball, and Bay Cove Human Services (Clinical Services).

Joseph Biederman: Dr. Joseph Biederman is currently receiving research support from the following sources: The Department of Defense, Ironshore, Vaya Pharma/Enzymotec, and NIH. In 2014, Dr. Biederman received honoraria from the MGH Psychiatry Academy for tuition-funded CME courses. He has a US Patent Application pending (Provisional Number #61/233,686) through MGH corporate licensing, on a method to prevent stimulant abuse. Dr. Biederman received departmental royalties from a copyrighted rating scale used for ADHD diagnoses, paid by Ingenix, Prophase, Shire, Bracket Global Sunovion, and Theravance; these royalties were paid to the Department of Psychiatry at MGH. In 2013, Dr. Biederman received an honorarium from the MGH Psychiatry Academy for a tuition-funded CME course. He received research support from APSARD, ElMindA, McNeil, and Shire. Dr. Biederman received departmental royalties from a copyrighted rating scale used for ADHD diagnoses, paid by Shire and Sunovion; these royalties were paid to the Department of Psychiatry at MGH.

Stephen Faraone: In the past year, Dr. Faraone received income, travel expenses and/or research support from and/or has been on an Advisory Board for Pfizer, Ironshore, Shire, Akili Interactive Labs, CogCubed, Alcobra, VAYA Pharma, Neurovance, Impax, NeuroLifeSciences and research support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). His institution is seeking a patent for the use of sodium-hydrogen exchange inhibitors in the treatment of ADHD. In previous years, he received consulting fees or was on Advisory Boards or participated in continuing medical education programs sponsored by: Shire, Alcobra, Otsuka, McNeil, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer and Eli Lilly. Dr. Faraone receives royalties from books published by Guilford Press: Straight Talk about Your Child’s Mental Health and Oxford University Press: Schizophrenia: The Facts.

Amy Yule: Dr. Amy Yule received grant support from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Pilot Research Award for Junior Faculty supported by Lilly USA, LLC.

Janet Wozniak: In 2013-2014, Janet Wozniak MD has received research support from Merck/Schering-Plough and income from MGH Psychiatry Academy. In the past she has received research support, consultation fees or speaker’s fees from: Eli Lilly, Janssen, Johnson and Johnson, McNeil, Pfizer, Shire. She is author of the book, “Is Your Child Bipolar” published May 2008, Bantam Books. In 2013-2014, her spouse received income from Associated Professional Sleep Societies, Cambridge University Press, Gerson Lerman Group, MGH Psychiatry Academy, Summer Street Partners, UCB, Cantor Colburn. In the past, he has received support, consultation fees, royalties or speaker’s fees from: Axon Labs, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Cambridge University Press, Covance, Cephalon, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Impax, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, King, Luitpold, Novartis, Neurogen, Novadel Pharma, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, Sepracor, Takeda, UCB (Schwarz) Pharma, UptoDate, Wyeth, Xenoport, Zeo.

MaryKate Martelon, Courtney Zulauf, Jesse Anderson, and Ronna Fried: The authors have no conflict of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

References

- 1.Youngstrom EA, Birmaher B, Findling RL. Pediatric bipolar disorder: validity, phenomenology, and recommendations for diagnosis. Bipolar Disord 2008. February;10(1 Pt 2):194–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007. May;64(5):543–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Axelson D, Birmaher B, Strober M, et al. Phenomenology of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006. October;63(10):1139–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geller B, Tillman R, Bolhofner K, Zimerman B, Strauss NA, Kaufmann P. Controlled, blindly rated, direct-interview family study of a prepubertal and early-adolescent bipolar I disorder phenotype: morbid risk, age at onset, and comorbidity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006. October;63(10):1130–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wozniak J, Petty CR, Schreck M, Moses A, Faraone SV, Biederman J. High level of persistence of pediatric bipolar-I disorder from childhood onto adolescent years: a four year prospective longitudinal follow-up study. J Psychiatr Res 2011. October;45(10):1273–1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Birmaher B, Axelson D. Course and outcome of bipolar spectrum disorder in children and adolescents: a review of the existing literature. Dev Psychopathol 2006. Fall;18(4):1023–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldstein BI, Levitt AJ. Further evidence for a developmental subtype of bipolar disorder defined by age at onset: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Am J Psychiatry 2006. September;163(9):1633–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rounsaville BJ, Anton SF, Carroll K, Buddle D, Prusoff BA, Gawin F. Psychiatric diagnoses of treatment-seeking cocaine abusers. Archives of General Psychiatry 1991;48:43–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, et al. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. JAMA 1990;264:2511–2518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin PI, McInnis MG, Potash JB, et al. Clinical correlates and familial aggregation of age at onset in bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163:240–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perlis R, Miyahara S, Marangell L, et al. Long-Term implications of early onset in bipolar disorder: data from the first 1000 participants in the systematic treatment enhancement program for bipolar disorder (STEP-BD). Biological Psychiatry 2004;55(9):875–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilens TE, Biederman J, Adamson JJ, et al. Further evidence of an association between adolescent bipolar disorder with smoking and substance use disorders: a controlled study. Drug Alcohol Depend 2008. June 1;95(3):188–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Birmaher B, Axelson D, Strober M, et al. Clinical course of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006. February;63(2):175–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldstein BI, Strober MA, Birmaher B, et al. Substance use disorders among adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Bipolar Disord 2008. June;10(4):469–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biederman J, Faraone SV, Hatch M, Mennin D, Taylor A, George P. Conduct disorder with and without mania in a referred sample of ADHD children. Journal of Affective Disorders 1997;44(2–3):177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weinberg NZ, Glantz MD. Child psychopathology risk factors for drug abuse: Overview. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology 1999;28(3):290–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldstein BI, Strober M, Axelson D, et al. Predictors of first-onset substance use disorders during the prospective course of bipolar spectrum disorders in adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2013. October;52(10):1026–1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ambrosini PJ. Historical development and present status of the schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children (K-SADS). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2000;39(1):49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M, First MB. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). I: History, rationale, and description. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992;49(8):624–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilens T, Biederman J, Wozniak J, Gunawardene S, Wong J, Monuteaux M. Can Adults with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder be Distinguished from those with Comorbid Bipolar Disorder: Findings from a Sample of Clinically Referred Adults. Biological Psychiatry 2003;54(1):1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stata Corporation. Stata User’s Guide: Release 9 College Station, TX: Stata Corp LP; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charach A, Yeung E, Climans T, Lillie E. Childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and future substance use disorders: comparative meta-analyses. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2011. January;50(1):9–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geller B, Tillman R, Bolhofner K, Zimerman B. Child bipolar I disorder: prospective continuity with adult bipolar I disorder; characteristics of second and third episodes; predictors of 8-year outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2008. October;65(10):1125–1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Delbello MP, Hanseman D, Adler CM, Fleck DE, Strakowski SM. Twelve-month outcome of adolescents with bipolar disorder following first hospitalization for a manic or mixed episode. Am J Psychiatry 2007. April;164(4):582–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kozloff N, Cheung AH, Schaffer A, et al. Bipolar disorder among adolescents and young adults: results from an epidemiological sample. J Affect Disord 2010. September;125(1–3):350–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strober M, Schmidt-Lackner S, Freeman R, Bower S, Lampert C, DeAntonio M. Recovery and relapse in adolescents with bipolar affective illness: A five-year naturalistic, prospective follow-up. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 1995;34(6):724–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldstein BI, Bukstein OG. Comorbid substance use disorders among youth with bipolar disorder: opportunities for early identification and prevention. J Clin Psychiatry 2010. March;71(3):348–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perlis RH, Brown E, Baker RW, Nierenberg AA. Clinical features of bipolar depression versus major depressive disorder in large multicenter trials. Am J Psychiatry 2006. February;163(2):225–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McElroy S, Altshuler L, Suppes T, et al. Axis I Psychiatric comorbidity and its relationship to historical illness variables in 288 patients with bipolar disorder. Am J Psych 2001;158(3):420–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brook JS, Adams RE, Balka EB, Johnson E. Early adolescent marijuana use: risks for the transition to young adulthood. Psychol Med 2002;32(1):79–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geller B, Tillman R, Craney JL, Bolhofner K. Four-year prospective outcome and natural history of mania in children with a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004. May;61(5):459–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilens TE, Martelon M, Anderson JP, Shelley-Abrahamson R, Biederman J. Difficulties in emotional regulation and substance use disorders: A controlled family study of bipolar adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013. February 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Carlson GA, Bromet EJ, Sievers S. Phenomenology and outcome of subjects with early- and adult-onset psychotic mania. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157(2):213–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lewinsohn PM, Klein DN, Seeley JR. Bipolar disorder during adolescence and young adulthood in a community sample. Bipolar Disord 2000. September;2(3 Pt 2):281–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilens TE, Biederman J, Abrantes AM, Spencer TJ. Clinical characteristics of psychiatrically referred adolescent outpatients with substance use disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997. July;36(7):941–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mezzich AC, Tarter RE, Hsieh Y, Fuhrman A. Substance abuse severity in female adolescents. Association between age at menarche and chronological age. The American Journal on Addictions 1992;1:217–221. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stowell R, Estroff TW. Psychiatric disorders in substance-abusing adolescent inpatients: A pilot study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 1992;31:1036–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Winokur G, Coryell W, Akiskal HS, et al. Alcoholism in manic-depressive (bipolar) illness: Familial illness, course of illness, and the primary-secondary distinction. American Journal of Psychiatry 1995;152(3):365–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Strakowski S, Tohen M, Stoll A, Faedda G, Goodwin D. Comorbidity in mania at first hospitalization. American Journal of Psychiatry 1992;149(4):554–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strakowski S, Sax K, McElroy S, Keck P, Hawkins J, West S. Course of psychiatric and substance abuse syndromes co-occurring with bipolar disorder after a first psychiatric hospitalization. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 1998;59(9):465–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tarter RE, Kirisci L, Mezzich A, et al. Neurobehavioral disinhibition in childhood predicts early age at onset of substance use disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2003. June;160(6):1078–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gignac M, Wilens TE, Biederman J, Kwon A, Mick E, Swezey A. Assessing cannabis use in adolescents and young adults: what do urine screen and parental report tell you? J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2005. October;15(5):742–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]