Abstract

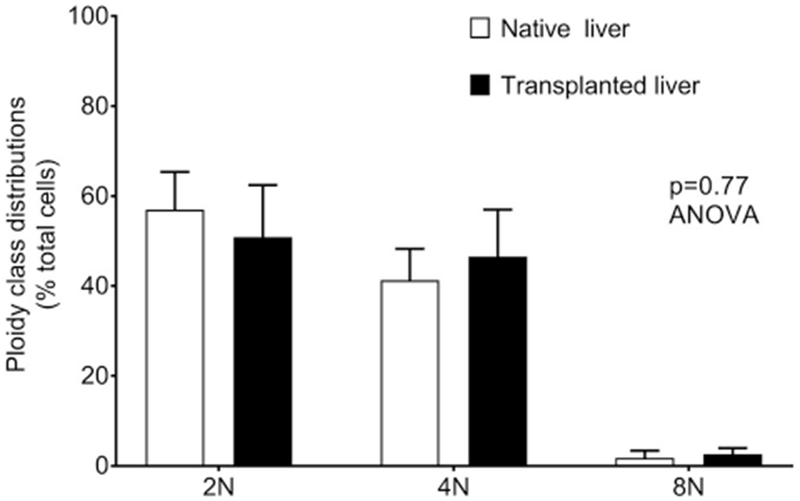

Scaffolds from healthy placentae offer advantages for tissue engineering with undamaged matrix, associated cytoprotective molecules, and embedded vessels for revascularization. As size disparities in human placenta and small recipients hamper preclinical studies, we studied alternative of bovine placentomes in smaller size ranges. Multiple cow placentomes were decellularized and anatomical integrity was analyzed. Tissue engineering used inbred donor rat livers. Placentomes were hepatized and immediately transplanted in rats with perfusion from portal vein and drainage into inferior vena cava. Cows yielded 99 ± 16 placentomes each. Of these, approximately 25% had 3 to 9 cm diameter and 7 to 63 ml volume, which was suitable for transplantation. After decellularization, angiography and casts documented 100% of vessels and vascular networks were well-perfused without disruptions or leaks. The residual matrix also remained intact for transplantation of placentomes. Perfusion in transplanted placentomes was maintained over up to 30 days. Liver tissue reassembled with restoration of hepatic acinar and sinusoidal structure. Transplanted tissue was intact without apoptosis, or necrosis. Hepatic functions were maintained. Preservation of hepatic homeostasis was verified by cytofluorimetric analysis of hepatocyte ploidy. The prevalence in healthy and transplanted liver of diploid, tetraploid and higher ploidy classes was similar with 57%, 41% and 2% versus 51%, 46.5% and 2.6%, respectively, p = 0.77, ANOVA.

Conclusions:

Cow placentomes will allow therapeutic development with disease models in small animals. This will also advance drug or toxicology studies. Portasystemic interposition of engineered liver will be particularly suitable for treating hepatic insufficiencies (metabolic, secretory or detoxification needs), including for children or smaller adults.

Keywords: Placenta, Portal hypertension, Regeneration, Transplantation, Vascular biology

1. Introduction

Tissue engineering for regenerative medicine requires testing efficacy of scaffolds and donor cells in disease models, especially in well-characterized small animals [1,2]. Studies of genetic or acquired diseases, e.g., liver-related metabolic deficits, enzyme deficiencies or injuries, will also be advanced by tissue engineering in small animals [3]. For this purpose, decellularized scaffolds supporting significant amounts of tissue are of much interest. Major gaps remain in engineering organs by alternative approaches, e.g., seeding of stem cell-derived constructs in ectopic sites, where problems related to vascularization, cell differentiation or proliferation of differentiated cells to assume significant masses pose difficulties [2]. By contrast, liver constructs in decellularized scaffolds have been successfully transplanted in small animals, such as rats [4–6]. However, transplantation of recellularized scaffolds with liver cells has yielded only short-term graft survival. Graft loss has resulted from thrombosis in blood vessels due to inability in restoring endothelial lining. Moreover, in recellularized scaffolds it has been difficult to restore acinar organization of liver. This acinar organization, incorporating interactions of hepatocytes with other specialized cell types present in hepatic sinusoids, is necessary for tissue homeostasis. The quality of scaffolds has been another significant concern; for instance, extracellular matrix (ECM) components or molecules benefiting recellularization may be degraded by diseases, injuries or post-mortem tissue alterations. Although, efforts for ECM modifications have previously been undertaken [7,8], these have not progressed to major applications.

To develop additional sources of decellularized scaffolds, we investigated the potential of healthy placenta [9]. This tissue offers many benefits: Placenta is universally available; it may be rapidly accessed; vascular structures include arterial and venous inlets and outlets for transplantation; decellularized placental ECM retains angiogenic and cytotrophic factors, e.g., VEGF, PDGF or HGF [10]. The potential of decellularized placental scaffold was tested in animal studies by assembly of tissue units containing all native liver cell types [11]. This principle utilized experiences with ectopic transplantation in rats of liver fragments or pancreatic islets (within vascularized intestinal segments or large veins) [12–15]. The implanted liver units in hepatized human placenta were well-perfused after transplantation in large animals (sheep) [11]. Consequently, over several weeks, transplanted liver tissue retained morphological and functional integrity. Also, in sheep with induction of acute liver failure (ALF) by subtotal hepatectomy, transplantation of hepatized placenta provided metabolic support and induced liver regeneration. Therefore, tissue engineering with placental scaffolds will be highly significant. Further development will be advanced by studies in well-characterized small animals modeling human disease [1,3]. Appropriately sized structures will be particularly important for eventual applications in pediatric populations or small individuals.

To resolve this issue, bovine (cow) placentome attracted us due to its unique anatomy with multiple units including independent vascular structures [16–20]. A characteristic of bovine placentome is availability of high-density vessel networks for blood exchanges with a fetal side (cotyledon); and a maternal side (caruncule). The vascular tree incorporates centralized incoming and outgoing vessels that are eminently suitable for transplantation. As cow placentome is thinner than human placenta [20], we considered it will be readily decellularized, lyophilized and rehydrated, similar to our recently published experience with human placenta [11]. Here, we developed decellularized cow placentome for liver transplantation in rats with following specific objectives: 1) Would decellularized placentome be capable of supporting implanted liver by perfusion and transfer of nutrients, substrates, metabolic intermediates; and 2) Would transplanted liver be reassembled and maintain homeostasis. For tissue perfusion, we interposed hepatized grafts in-between portal vein and inferior vena cava (IVC) (portasystemic circulation). Since portal blood contains nutrients and trophic factors, this should have benefited liver tissue after transplantation [21].

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Regulatory approval

Animal protocols were approved by Georgian National Medical Research Institute (Permit 14-48). All institutional and applicable guidelines were followed.

2.2. Animals

Cows were from an agricultural farm (Agara Village, Georgia). These were bred as usual. Placentomes were collected after routine birthing (n = 5). Lewis rats aged 8–10 weeks and weighing 200–250 g were bred at Tbilisi State Medical University. Rats were kept under 12-h day-night cycles. For surgery, rats were anesthetized by 60–100 mg/kg ketamine and 5–10 mg/kg xylazine i.p. (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA).

2.3. Placentome decellularization

Blood was cleared by irrigating placentomes with normal saline containing 1 U heparin per ml (Sigma-Aldrich, Schnelldorf, Germany). Placentome artery was perfused by 0.01%, 0.1% and 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS; Sigma-Aldrich) in distilled water at 1 ml per min for three consecutive 24 h periods each, as previously described [11], and with minor modifications of another previously described protocol [22]. To remove SDS, decellularized placentomes were irrigated by water for 30 min, 1% Triton X-100 in water for 1 h and normal saline for 3h. To inactivate contaminants, e.g., prions, placentomes were autoclaved in wet-cycle and incubated in 4% sodium hypochlorite for 24 h and 0.1% peracetic acid (Sigma) for another 3 h. Placentomes were then lyophilized (Power Dry PL 6000 Freeze Dryer, China). Gamma radiation to 15 Gray was used for further sterilization. This was followed by storage of placentomes in bags at room temperature.

2.4. Tissue DNA measurement

DNA was isolated from 30 mg tissue samples before and after decellularization of placentome with a commercial kit (G-spin Total DNA Extraction Mini kit; iNtRON Biotechnology, Inc., Seongnam, South Korea). Total DNA content was measured by spectrophotometer at 260 nm (NanoDrop 1000; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA).

2.5. Vascular anatomy of placentomes

For casts, placentome artery and vein were cannulated to instill 50% latex in water (NAIRIT L-3, NAIRIT) or Minimum Red oxide of lead (Pb304 + PbO [M −]) in olive oil. For angiography, 52% iodinated radiocontrast (Bilitrast, Russia) was used.

2.6. Electron microscopy (EM)

Tissues were fixed in glutaraldehyde and dried in Tousimis Samdri-780 critical point dryer (Tousimis Research Corp., Rockville, MD, USA). Ultrathin sections were sputter-coated with gold before imaging (Scanning Electron Microscope, Hitachi Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

2.7. Hepatization of placentome

Lyophilized placentome was rehydrated in normal saline for 60 min. Placentome and vessels were bonded with1000 U heparin per ml in 1% protamine sulfate and 1% glutaraldehyde (Sigma) at 4 °C, as previously described [23]. Donor rats were given 500 U heparin i.v. for anticoagulation Portal vein was isolated by midline laparotomy and cannulated. Blood was cleared from liver by sterile Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) (Sigma). Liver was excised and divided by a surgical knife in HBSS to obtain 1 mm3 fragments. Large fragments were removed by passage through two layers of surgical gauze in HBSS under gravity. Liver tissue 3 g was injected into decellularized placentome and also placed on maternal side and in-between fetal side. The edges of placentome overlaid with liver fragments were stitched together by 5-zero silk (Ethicon, New Jersey, USA). Latex dye casts were obtained for vessel leaks.

2.8. Portacaval interposition of hepatized placentome in rats

Portal vein was isolated by midline laparotomy. A 20-gauge blunt-tipped needle was placed alongside portal vein. A ligature of 5-zero silk (Ethicon) encircling portal vein and needle was tied, and needle was withdrawn from ligature, as previously established [24]. Hepatized placentome was positioned between portal vein and IVC. “End-to-side” anastomoses of placentome artery to portal vein and placentome vein to IVC used 8-zero Proline with atraumatic needles (Ethicon) under operating microscope (Zeiss, Germany). Caruncule (maternal side) was attached to inner abdominal wall by 5-zero sutures. Radiocontrast angiography was performed for perfusion in transplanted placentome. For placentome vessel casts latex dyes were used.

2.9. Histological studies

Tissue were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Five 5 μm thick sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or Masson’s trichrome. Microscopic examination was for following: Tissue morphology; ischemia or necrosis; congestion or occlusion of vessels and sinusoids; apoptosis, cell drop-out, steatosis or hydropic changes; excessive reticulin or collagen. For hepatic ploidy distributions, the area of hepatocyte nuclei with hematoxylin staining was scored in multiple images from animals by Cytation5 instrument (BioTek, Winooski, VT). These nuclear size classes were binned compared with diploid DNA (2 N) standards into 2 N, 4 N and 8 N + classes by Excel software (Microsoft Corp., Seattle, CA) as previously described [25].

2.10. Rat groups

Twenty rats served as tissue donors or controls for tissue studies. For placentome transplantation, 18 rats were used – these were euthanized 2 h and 1, 3, 7–10, 14–15, and 30 days after transplantation (n = 3 ea).

2.11. Statistics

Data are reported as means ± SEM. For paired comparisons, non-parametric data, or ploidy distributions, t-test, Mann-Whitney test, and Wilcoxon’s rank sum test were used, respectively, by GraphPad Prism7 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA). p < 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

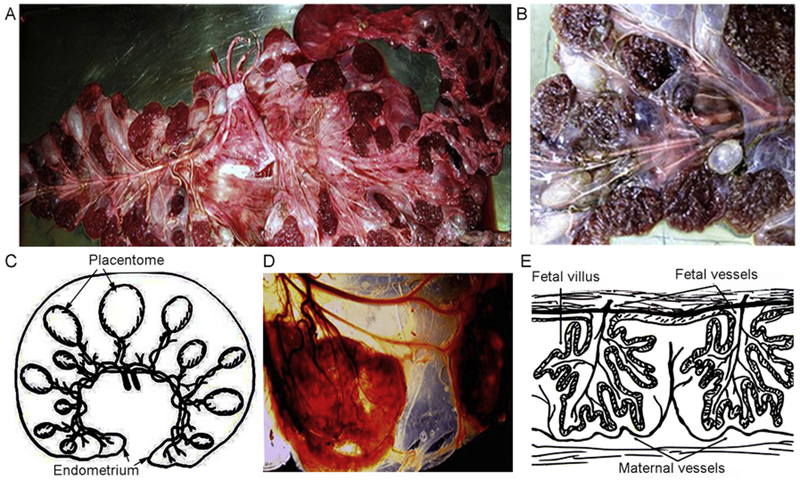

Placentomes from cows were arranged in orderly rows (Fig. 1A-C). This arrangement has been reported previously in healthy gravid cows [17–19,26]. Placentomes were endowed individually with arterial and venous blood vessels leading toward rich vascular networks (Fig. 1D, E). These included secondary and tertiary vessels with arterioles, terminal capillaries and venous tributaries.

Fig. 1.

Anatomical organization of cow placentome. (A, B) Gross morphology shortly after delivery of cow afterbirth with major vessels feeding placentomes (fetal surface) (A) and caruncules (maternal surface). (C) Schematic representation of the arrangement of placentome in uterine horn. (D) Vascular organization of a cotyledon/caruncule with blood vessels feeding into the internal vascular network contributing in fetal-maternal blood circulation. (E) Schematic representation of the vascular network and relationships between fetal and maternal blood vessels. Panels in C and E were modified and redrawn from Cornells et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013; 110, E828–837.

Each of 5 cows contained 99 ± 16 placentomes (range, 80 to 120). Dimensions (diameter) of placen tomes were (n = 495): 3–5 cm, 5 ± 2%; 6–9 cm, 17 ± 3%; 10–13 cm, 24 ± 3%; 14–16 cm, 36 ± 2%; 17–20 cm, 14 ± 4%; and > 20 cm, 4 ± 1%. Estimated volumes corresponding to these sizes were (ranges): 7–19 ml; 28–63 ml; 78–132 ml; 154–200 ml; 340–470 ml; and > 500 ml, respectively. Placen tomes of 3–5 cm diameter and 7–19 ml volume were suitable for transplantation in rats. Each cow yielded ~25 such placentomes.

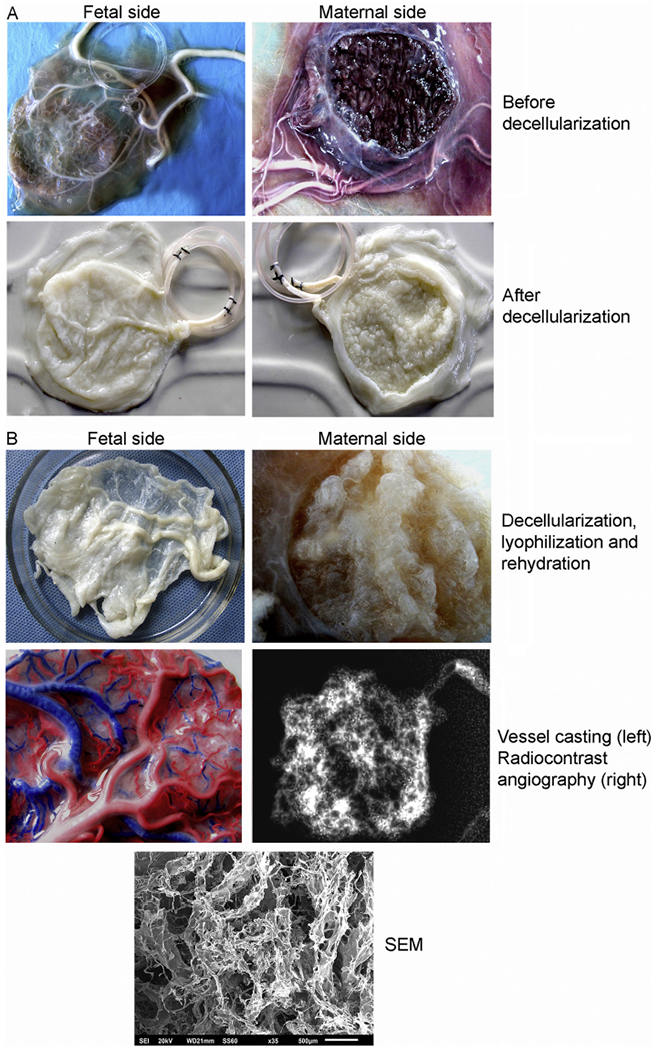

3.1. Decellularization and lyophilization of placentome

Vessels in placentomes were readily cannulated for decellularization procedures (Fig. 2A). After decellularization, vessels in cotyledons and caruncules remained intact. Removal of nucleated cells was verified by histology of scaffold (not shown). Scanning EM demonstrated complex structure, as expected, with vascular spaces interspersed amidst ECM components. Latex dyes flowed from larger vessels to smaller capillaries without leaks, indicating intact microvasculature. To facilitate transplantation studies, placentomes were prospectively lyophilized and stored. Rehydration with saline and heparin bonding of lyophilized placentome led to redistension of vessels and ECM components (Fig. 2B). Evaluation of vascular integrity with latex dyes indicated that lyophilization had no effect on vascular patency or reperfusion of placentomes (n = 10). These casts verified filling in each specimen examined of larger vessels, arterioles and venules. In all specimens, capillary networks were well-visualized. Similarly, radiocontrast angiography in each specimen verified major vessels and capillary networks were rapidly filled by arteries and drained equally rapidly by venous tributaries. Radiocontrast filled vessels throughout the placentomes. We noted neither absence of radiocontrast to suggest vascular obstructions; nor accumulation of radiocontrast in localized areas to suggest vascular disruptions.

Fig. 2.

Decellularization, lyophilization and rehydration of placentome. (A) Gross appearances of major inlet and outlet vessels in freshly harvested cotyledons (fetal side) and caruncules (maternal side). Representative examples are provided of placentomes before (top) and after decellularization (bottom). The latter resulted in colorless and flaccid structures with loss of components other than ECM components although vessels were apparent. (B) Gross appearance of decellularized placentomes after lyophilization and then rehydration (top). Vascular casts with latex containing red or blue dyes injected into the major artery and vein, respectively, of decellularized placentome showing intact vessels and downstream networks (middle, left). Radiocontrast angiography verified intact vessels with free inward and outward flows (middle, right). Bottom panel indicated by SEM refers to scanning EM of decellularized placentome with intact ECM with protrusions of fibers and fibrils around other structures, including vascular spaces (scale bar, 5 μm). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

The intact placentome prior to decellularization exhibited on average 4.6 μg DNA per mg tissues. After decellularization, we detected at most 40 ng DNA per mg tissues.

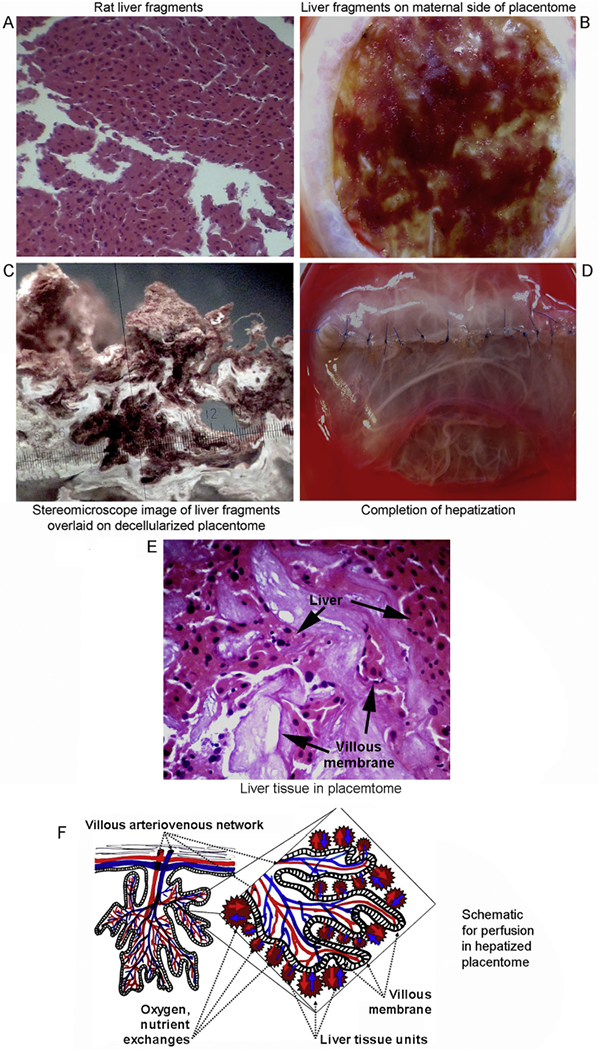

3.2. Construction and transplantation of hepatized placentome

Donor rat liver fragments were demonstrated by histological examination to be intact (Fig. 3A). These fragments retained hepatic acinar structure. Presence was confirmed of healthy hepatocytes, liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSEC), Kupffer cells (KC) and hepatic stellate cells (HSC). Liver fragments were distributed on the maternal side of placentomes between fetal villi. Implantation of 3 g of tissue in placentomes of 3–5 cm diameter represented 10–12% of donor liver in recipient rats (Fig. 3B). Microscopic examination verified placentome ECM and implanted liver fragments were in close proximity (Fig. 3C). Finally, the implanted liver was enclosed within the caruncule by suturing of the edges, which imparted additional mechanical strength to the construct (Fig. 3D). The hepatized placenta will have been perfused by blood and interstitial fluid emanating from capillaries in maternal side as well as those in fetal villi, which was verified by histological studies (Fig. 3E). This will have simultaneously allowed mass transfer with exchange of gases, intermediary substrates or secretory products from cells, as demonstrated schematically (Fig. 3F). Release of bile produced by transplanted tissue into blood will have led to eventual disposal of excretory products into the intestine through the biliary excretory apparatus in the native liver. This will have been similar to excretion of bile after implantation of liver tissue in another ectopic site (small intestinal segments), as previously verified by radiotracer studies using 99mTc-mebrofenin [14].

Fig. 3.

Construction of hepatized placentome. (A) Gross appearance of rat liver fragments showing intact hepatic structures with sinusoids. Liver fragments contained healthy hepatocytes and other liver cell types. H&E staining, magnification ×40. (B) Overlay of liver fragments on caruncule (maternal surface) of decellularized cow placentome after lyophilization and rehydration. (C) Stereoscopic microscopy of decellularized placentome with liver microfragments (magnification ×850).(D) Hepatized placenta with sutures joining edges of caruncule overlaid with amnion to enclose implanted liver fragments. (E) Tissue section of hepatized placenta indicating proximity of implanted liver tissue to villi of placentome. H&E staining, magnification ×400. (F) Schematic model representing perfusion of transplanted liver from villi and interstitium in hepatized placentome.

3.3. Fate of transplanted hepatized placentome

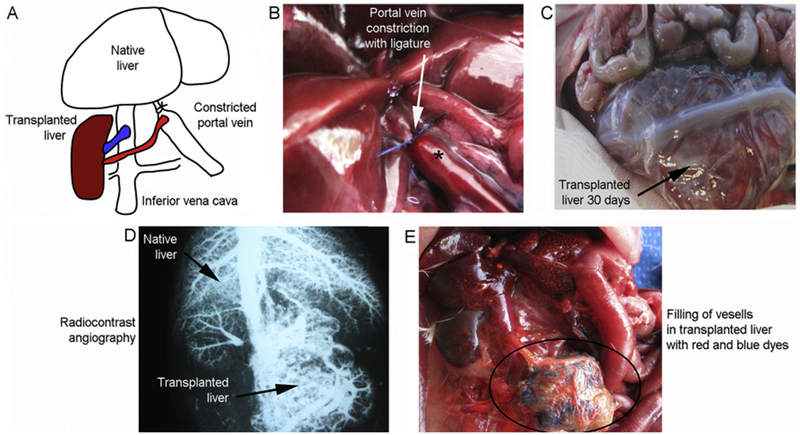

After pilot experiments, hepatized placentome was transplanted into multiple rats (n = 18).

All rats successfully survived surgery and recovered uneventfully. The surgical procedure was designed to interpose hepatized placentome in-between partially constricted portal vein and IVC (Fig. 4A). Inlet and outlet vessels in placentome allowed end-to-side anastomoses with portal vein and IVC. Controlled portal vein constriction divided portal blood flow to both native and transplanted livers (Fig. 4B). After vascular anastomoses and removal of clamps this provided excellent perfusion to transplanted liver. The native liver was equally well perfused without ischemic spots or altered color. Perfusion of native and transplanted livers was maintained after 2h and 1, 3, 7, 14, and 30 days (n = 3 ea per interval). All animals remained healthy with usual food intake and activities during study periods. Necropsy at each interval indicated vessel anastomoses were intact. Blood vessels of placentome anastomosed with portal vein were engorged with ongoing flow (Fig. 4C). At all intervals, native liver was healthy with neither atrophy nor hypertrophy. Transplanted liver in placentome was healthy with appropriate blood filling. Angiography in randomly selected rats verified perfusion – blood entered in transplanted liver from portal vein; blood exited from transplanted liver into IVC (Fig. 4D). Latex dye casts in transplanted liver verified intactness of major vessels and also capillary networks (Fig. 4E).

Fig. 4.

Transplantation of hepatized placentome in rats. (A) Schematic for placement of hepatized placentome between portal vein and IVC. Placentome artery was joined with portal vein for blood inflow and placentome vein with IVC for blood outflow. (B) Ligature encircling portal vein for calibrated constriction (by ~25% of diameter). After constriction, portal vein was engorged proximal to the ligature (asterisk). (C) Hepatized placentome 30 days after transplantation. Transplanted liver is distended with blood-filled vessels. (D) Angiographic image of rat 30 days after transplantation indicating simultaneous visualization of vessels and perfusion in both native and transplanted livers (arrows). Note drainage from transplanted liver of contrast into IVC. (E) Latex cast at necropsy of an animal 30 days after liver transplantation with lead tetroxide dye via portal vein and IVC. In hepatized placentome, major and minor vessels along with capillaries are filled (encircled area).

Histology of explanted hepatized placentome was informative: over 2 h to 3 days hemorrhagic exudates surrounded transplanted liver (Fig. 5A–C). These included neutrophils and monocytes. Liver fragments were separated from one another by exudates but were healthy without ischemia or necrosis. Blood vessels and sinusoids were without congestion or thromboses. After 7 days, inflammatory exudates in hepatized placenta had subsided. Between 7 and 14 days (Fig. 5D, E), transplanted liver reassembled in confluent sheets with blood-filled spaces and sinusoids. Transplanted tissue was interspersed with placentome-derived ECM components. This morphology was maintained subsequently over 30 days (Fig. 5F). Hepatocytes in transplanted tissue were healthy. No differences were observed in transplanted liver or donor and native livers in apoptosis, steatosis, cell drop-out, or hydropic changes. In healthy donors and transplanted liver 0 to 5 such cells were observed per 1000 or more hepatocytes, p > 0.05, Mann-Whitney rank sum tests. Blood vessels were re-endothelialized. Masson’s trichrome staining excluded excessive collagen or reticulin in transplanted liver. ECM components arising from placentome were present but transplanted liver did not have fibrosis. Staining for glycogen content in hepatocytes from these livers was similar (not shown).

Fig. 5.

Morphology of transplanted liver in placentome. (A–B) Liver in placentome 2 h (A) or Id after transplantation (B). Note separation of liver tissue fragments immediately after transplantation. ECM from placentome was interspersed with implanted liver tissue (panel on top right). (C–E) Transplanted liver after 3, 7 and 14 d showing early accumulation of neutrophils and monocytes (C) followed by reassembly of hepatic tissue with restoration of acinar organization and sinusoids. Presence of bile duct structures is also noteworthy (D, E). Tissues remained healthy with no necrosis or obvious damage. (F) Transplanted liver after 30d with placentome ECM (top left and bottom right panels). Transplanted liver in confluent sheets with blood-filled spaces, acinar organization and sinusoids (upper middle panels). Note absence of hepatic apoptosis, necrosis, steatosis or hydropic changes with cells lining sinusoids (upper right panel). Placentome artery with endothelial cells (arrows) and stroma (lower left panel). Occasional bile ducts are also noted (bottom middle panel). Masson’s trichrome (bottom right panel) visualized placentome ECM. Excessive collagen or reticulin were absent. H&E staining in all other panels. Original magnifications are as indicated.

On occasion, tissue fragments harbored bile ducts. This was similar to previous tissue transplantation studies. As established for ectopic liver transplants in vascularized small intestinal segments or human placenta constructs anastomosed to femoral vessels, bile will have entered blood followed by excretion into intestines from the native liver [11,14]. The excretion by specific bile transporters of ligands, such as that of MRP2-dependent 99mTc-mebrofenin excretion [27], was verified in these previous tissue transplantation studies.

In rats after partial hepatectomy (PH) or portal vein occlusion, either excessive or deficient portal perfusion may alter hepatic ploidy [28]. Alteration in ploidy classes is a fundamental response of hepatocytes to mitogenic signals and/or injuries [29]. Ploidy differences provide ways to address liver tissue stability over long periods. Therefore, we analyzed liver tissues from healthy controls and hepatized placenta 30 days after transplantation. The sizes of hepatocyte nuclei were compared morphometrically in healthy control liver (n = 3765) and transplanted liver (n = 2755). Prevalence of diploid (2 N), tetraploid (4 N) and octaploid (8 N + ) classes in these tissues was similar (Fig. 6). The 2N, 4N and 8N + classes constituted 57%, 41% and 2% versus 51%, 46.5% and 2.6% in healthy and transplanted liver, respectively, p = 0.77, ANOVA. Hence, portacaval interposition and perfusion of transplanted liver by portal blood maintained tissue homeostasis.

Fig. 6.

Ploidy class distributions of hepatocytes. Cumulative analysis of hepatocytes from multiple tissue sections for 2 N (diploid), 4 N (tetraploid) and 8 N + (octaploid) classes. Hepatic ploidy distributions were similar in donor rat livers and transplanted livers in placentomes.

4. Discussion

This study establishes that bovine placentome-derived scaffolds may be effectively developed and tested in small animals. Wide access to tissues from cows under defined microbial and hygienic conditions will advance applications of tissue transplantation. Storage of decellularized placentomes after lyophilization will be quite convenient for undertaking prospective studies. Extrapolating results with cow placentome in small animals will be particularly helpful for use of cell- or tissue constructs in people.

The anatomy of cow placentome differs in significant ways from human placenta: Bovine venous system outweighs arterial vessel number and volume in humans; bovine capillary complex is less dense than in humans; bovine maternal vasculature constitutes a closed system, whereas human placenta contains open lacunal intervillous spaces [20]. Cow placentome and human placenta do share anatomical arrangements of primary, intermediate, and terminal vessels. However, primary vessels in cow placentome are longer – this actually simplifies transplantation in animals and will be helpful for pediatric applications in people. For placement of liver in caruncule (maternal side) of cow placentome, its discoid structure was convenient.

After decellularization, intact vessels and structures in placentome was similar to human placenta [11]. To obtain complex organs, such as liver, three-dimensional scaffolds with networks of branched vessels and capillaries are critical for perfusion. Lyophilized placentomes were rehydrated without loss of ECM and vessel networks – large, small, capillaries. Decellularized placentome scaffold and vessels withstood mechanical needs for reanastomosis and perfusion in animals.

Tissue scaffolds may differ in immobilized factors that support not only implanted tissue but additionally foster recruitment of endothelial/mesenchymal/stromal cells for angiogenesis and vascularization. Studies have established that decellularized ECM of human placenta retains multiple growth factors [10]. This promotes endothelial cell migration in hepatized placental vessels from hosts [11]. Similarly, ECM in cow placentome contains multiple collagens-types I, III and IV, integrins, matrix-type metalloproteinases, etc. [30,31]. Also, ECM in cow placentome contains VEGF and its receptors [32]. These molecules will have advanced re-endothelialization and formation of stroma in hepatized placentome.

The process of transplanted liver reorganization, including early inflammatory exudates, followed by tissue reassembly, recapitulated liver transplantation in ectopic sites [9,12–15]. Portasystemic interposition provided portal blood supply to hepatized placentome and supported tissue homeostasis. Supply of blood and interstitial fluid from maternal vessels and fetal capillaries and villi should have allowed exchanges of gases, intermediary substrates, metabolites and secretory or excretory products. The critical role of interstitium in tissue maintenance has recently been recognized [33]. This inveterate interstitial component allows survival of migratory cells. In studies here, transplanted tissue was without ischemia, necrosis or injury (apoptosis, cell drop-out, steatosis, hydropic changes), No fibrosis was observed suggesting absence of recruitmentor activation of inflammatory cells, e.g., KC or HSC, that contribute in fibrogenesis [34]. Multiple cell types in constructs will have promoted beneficial interactions.

Analysis of ploidy states in hepatized placentome verified tissue homeostasis. If portal blood supply becomes mismatched to tissue needs, e.g., after two-thirds PH, remnant liver suddenly receives 3-fold more blood, which leads to polyploidy [28,29,35]. Excessive polyploidy coupled with DNA damage, as after ischemia-reperfusion injury or radiation, leads to cell growth-arrest and eventually to cell losses [36,37]. By contrast, insufficient supply of portal blood causes hepatic atrophy [21,38]. Therefore, the absence of advancement in ploidy states in hepatized placentome excluded hepatic hypertrophy on the one hand and atrophy on the other.

Multiple sizes of placentomes will allow organ transplantation in small, medium or larger animals. Similarly, this will be extremely useful for pediatric applications. By contrast, bigger size of human placental cotyledons (volume, 6 to 14 ml), prevents transplantation in small animals and will be difficult for pediatric populations. Therefore, small animal studies will permit further development of cow placentome for therapeutic applications: Portasystemic shunts for relieving portal hypertension are often complicated by encephalopathy, which may be avoided by hepatic interposition; liver failure may be ameliorated by metabolic functions or secreted proteins (albumin, coagulation factors, etc.); enzyme deficiency states may be corrected by healthy liver. For diabetes, cotransplantation of liver and pancreatic islets will similarly be relevant.

In portasytemic interposition balanced blood supply to transplanted tissues will be critical. This is substantiated by clinical experiences of auxiliary partial orthotopic liver transplantation [39]. This procedure has had variable outcomes related to perfusion differences in native versus grafted livers.

To delineate metabolic, enzymatic and synthetic functions in transplanted liver, prospective studies will be required in various animal models. These mechanisms were beyond the scope of this study. Other critical issues in tissue engineering should also be worthy of study with placentome transplants, e.g., reorganization of stem cell-derived or other cell types, cell interactions, induction of angiogenesis, etc. Disease models could be obtained by transplanting human tissues in immuno deficient animals, including for drug development, toxicology studies, or gene therapy.

Acknowledgements

Sanjeev Gupta and Yogeshwar Sharma were supported in part by National Institutes of Health [grants R01-DK071111 and P30-DK41296].

Abbreviations:

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- EM

electron microscopy

- HBSS

Hanks’ balanced salt solution

- HSC

hepatic stellate cells

- i.p.

intraperitoneal

- i.v.

intravenous

- IVC

inferior vena cava

- KC

Kupffer cells

- LSEC

liver sinusoidal endothelial cells

- OLT

orthotopic liver transplantation

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PH

partial hepatectomy

- RT

room temperature

- SEM

standard error of mean

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

- TBS

tris-buffered saline

Footnotes

Statement of conflicts

The authors declare no conflicts of interest exist.

References

- [1].Langer R, Vacanti J, Advances in tissue engineering, J. Pediatr. Surg 51 (2016) 8–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Stevens KR, Scull MA, Ramanan V, Fortin CL, Chaturvedi RR, Knouse KA, Xiao JW, Fung C, Mirabella T, Chen AX, McCue MG, Yang MT, Fleming HE, Chung K, de Jong YP, Chen CS, Rice CM, Bhatia SN, In situ expansion of engineered human liver tissue in a mouse model of chronic liver disease, Sci. Transl. Med 9 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Forbes SJ, Gupta S, Dhawan A, Cell therapy for liver disease: from liver transplantation to cell factory, J. Hepatol 62 (2015) S157–S169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Wang Y, Nicolas CT, Chen HS, Ross JJ, De Lorenzo SB, Nyberg SL, Recent advances in decellularization and recellularization for tissue-engineered liver grafts, Cells Tissues Organs 203 (2017) 203–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ko IK, Peng L, Peloso A, Smith CJ, Dhal A, Deegan DB, Zimmerman C, Clouse C, Zhao W, Shupe TD, Soker S, Yoo JJ, Atala A, Bioengineered transplantable porcine livers with re-endothelialized vasculature, Biomaterials 40 (2015) 72–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Uygun BE, Soto-Gutierrez A, Yagi H, Izamis ML, Guzzardi MA, Shulman C, Milwid J, Kobayashi N, Tilles A, Berthiaume F, Hertl M, Nahmias Y, Yarmush ML, Uygun K, Organ reengineering through development of a transplantable recellularized liver graft using decellularized liver matrix, Nat. Med 16 (2010) 814–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Sun G, Shen YI, Kusuma S, Fox-Talbot K, Steenbergen CJ, Gerecht S, Functional neovascularization of biodegradable dextran hydrogels with multiple angiogenic growth factors, Biomaterials 32 (2011) 95–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Oh SH, Ward CL, Atala A, Yoo JJ, Harrison BS, Oxygen generating scaffolds for enhancing engineered tissue survival, Biomaterials 30 (2009) 757–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kakabadze Z, Kakabadze A, Chakhunashvili D, Karalashvili L, Berishvili E, Sharma Y, Gupta S, Decellularized human placenta supports hepatic tissue and allows rescue in acute liver failure, Hepatology 67 (2018) 1956–1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Choi JS, Kim JD, Yoon HS, Cho YW, Full-thickness skin wound healing using human placenta-derived extracellular matrix containing bioactive molecules, Tissue Eng. A 19 (2013) 329–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kakabadze Z, Kakabadze A, Chakhunashvili D, Karalashvili L, Berishvili E, Sharma Y, Gupta S, Decellularized human placenta supports hepatic tissue and allows rescue in acute liver failure, Hepatology (2017), 10.1002/hep.29713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kakabadze Z, Gupta S, Pileggi A, Molano RD, Ricordi C, Shatirishvili G, Loladze G, Mardaleishvili K, Kakabadze M, Berishvili E, Correction of diabetes mellitus by transplanting minimal mass of syngeneic islets into vascularized small intestinal segment, Am. J. Transplant 13 (2013) 2550–2557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kakabadze Z, Shanava K, Ricordi C, Shapiro AM, Gupta S, Berishvili E, An isolated venous sac as a novel site for cell therapy in diabetes mellitus, Transplantation 94 (2012) 319–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Joseph B, Berishvili E, Benten D, Kumaran V, Liponava E, Bhargava K, Palestro C, Kakabadze Z, Gupta S, Isolated small intestinal segments support auxiliary livers with maintenance of hepatic functions, Nat. Med 10 (2004) 749–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Berishvili E, Liponava E, Kochlavashvili N, Kalandarishvili K, Benashvili L, Gupta S, Kakabadze Z, Heterotopic auxiliary liver in an isolated and vascularized segment of the small intestine in rats, Transplantation 75 (2003) 1827–1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Rodriguez-Sosa JR, Rathi R, Wang Z, Dobrinski I, Development of bovine fetal testis tissue after ectopic xenografting in mice, J. Androl 32 (2011) 271–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Pfarrer C, Ebert B, Miglino MA, Klisch K, Leiser R, The three-dimensional feto-maternal vascular interrelationship during early bovine placental development: a scanning electron microscopical study, J. Anat 198 (2001) 591–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Schlafer DH, Fisher PJ, Davies CJ, The bovine placenta before and after birth: placental development and function in health and disease, Anim. Reprod. Sci 60-61 (2000) 145–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Leiser R, Krebs C, Klisch K, Ebert B, Dantzer V, Schuler G, Hoffmann B, Fetal villosity and microvasculature of the bovine placentome in the second half of gestation, J. Anat 191 (Pt 4) (1997) 517–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Leiser R, Krebs C, Ebert B, Dantzer V, Placental vascular corrosion cast studies: a comparison between ruminants and humans, Microsc. Res. Tech 38 (1997) 76–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Rozga J, Jeppsson B, Bengmark S, Hepatotrophic factors in liver growth and atrophy. Br. J. Exp. Pathol 66 (1985) 669–678. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Wang Y, Cui CB, Yamauchi M, Miguez P, Roach M, Malavarca R, Costello MJ, Cardinale V, Wauthier E, Barbier C, Gerber DA, Alvaro D, Reid LM, Lineage restriction of human hepatic stem cells to mature fates is made efficient by tissue-specific biomatrix scaffolds, Hepatology 53 (2011) 293–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Noishiki Y, Miyata T, A simple method to heparinize biological materials, J. Biomed. Mater. Res 20 (1986) 337–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Gupta S, Yemeni PR, Vemuru RP, Lee CD, Yellin EL, Bhargava KK, Studies on the safety of intrasplenic hepatocyte transplantation: relevance to ex vivo gene therapy and liver repopulation in acute hepatic failure, Hum. Gene Ther 4 (1993) 249–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Viswanathan P, Sharma Y, Gupta P, Gupta S, Replicative stress and alterations in cell cycle checkpoint controls following acetaminophen hepatotoxicity restrict hepatic regeneration, Cell Prolif (2018), 10.1111/cpr.12445 (March 5. doi: 10.1111/cpr.12445). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Cornells G, Heidmann O, Degrelle SA, Vernochet C, Lavialle C, Letzelter C, Bernard-Stoecklin S, Hassanin A, Mulot B, Guillomot M, Hue I, Heidmann T, Dupressoir A, Captured retroviral envelope syncytin gene associated with the unique placental structure of higher ruminants, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 110 (2013) E828–E837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Bhargava KK, Joseph B, Ananthanarayanan M, Balasubramaniyan N, Tronco GG, Palestro CJ, Gupta S, Adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette subfamily C member 2 is the major transporter of the hepatobiliary imaging agent (99m)Tc-mebrofenin, J. Nucl. Med 50 (2009) 1140–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Gupta S, Hepatic polyploidy and liver growth control, Semin. Cancer Biol 10 (2000) 161–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Duncan AW, Taylor MH, Hickey RD, Hanlon Newell AE, Lenzi ML, Olson SB, Finegold MJ, Grompe M, The ploidy conveyor of mature hepatocytes as a source of genetic variation, Nature 467 (2010) 707–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Boos A, Stelljes A, Kohtes J, Collagen types I, III and IV in the placentome and interplacentomal maternal and fetal tissues in normal cows and in cattle with retention of fetal membranes, Cells Tissues Organs 174 (2003) 170–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Dilly M, Hambruch N, Shenavai S, Schuler G, Froehlich R, Haeger JD, Ozalp GR, Pfarrer C, Expression of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2, MMP-14 and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase (TIMP)-2 during bovine placentation and at term with or without placental retention, Theriogenology 75 (2011) 1104–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Pfarrer CD, Ruziwa SD, Winther H, Callesen H, Leiser R, Schams D, Dantzer V, Localization of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptors VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 in bovine placentomes from implantation until term, Placenta 27 (2006) 889–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Benias PC, Wells RG, Sackey-Aboagye B, Klavan H, Reidy J, Buonocore D, Miranda M, Kornacki S, Wayne M, Carr-Locke DL, Theise ND, Structure and distribution of an unrecognized interstitium in human tissues, Sci. Rep 8 (2018) 4947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Benten D, Kluwe J, Wirth JW, Thiele ND, Follenzi A, Bhargava KK, Palestro CJ, Koepke M, Tjandra R, Volz T, Lutgehetmann M, Gupta S, A humanized mouse model of liver fibrosis following expansion of transplanted hepatic stellate cells, Lab. Investig (2018), 10.1038/s41374-017-0010-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Sigal SH, Rajvanshi P, Gorla GR, Sokhi RP, Saxena R, Gebhard DR Jr., Reid M, Gupta S, Partial hepatectomy-induced polyploidy attenuates hepatocyte replication and activates cell aging events, Am. J. Phys 276 (1999) G1260–G1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Gorla GR, Malhi H, Gupta S, Polyploidy associated with oxidative injury attenuates proliferative potential of cells, J. Cell Sci 114 (2001) 2943–2951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Malhi H, Gorla GR, Irani AN, Annamaneni P, Gupta S, Cell transplantation after oxidative hepatic preconditioning with radiation and ischemia-reperfusion leads to extensive liver repopulation, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 99 (2002) 13114–13119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Ren W, Chen G, Wang X, Zhang A, Li C, Lv W, Pan K, Dong JH, Simultaneous bile duct and portal vein ligation induces faster atrophy/hypertrophy complex than portal vein ligation: role of bile acids, Sci. Rep 5 (2015) 8455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Reddy MS, Rajalingam R, Rela M, Revisiting APOLT for metabolic liver disease: a new look at an old idea, Transplantation 101 (2017) 260–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]