Significance

Prions are infectious, self-propagating protein aggregates that are best known as the cause of the fatal transmissible spongiform encephalopathies in mammals. Unique among infectious agents because they lack nucleic acid, prions also exist in fungi, where they function as protein-based genetic elements. The recent identification of a bacterial prion-forming protein suggests that bacteria also harbor prions, but genetic tools for detecting prion-like behavior in bacteria are lacking. We describe the development of a bacteria-based genetic assay that reports on prion formation, and we use this assay to present evidence for a second bacterial prion protein, a DNA-binding protein from Campylobacter hominis. This genetic assay has the potential to facilitate the investigation of prion-like phenomena in all domains of life.

Keywords: prions, protein-based heredity, SSB, Sup35, Escherichia coli

Abstract

Prions are infectious, self-propagating protein aggregates that are notorious for causing devastating neurodegenerative diseases in mammals. Recent evidence supports the existence of prions in bacteria. However, the evaluation of candidate bacterial prion-forming proteins has been hampered by the lack of genetic assays for detecting their conversion to an aggregated prion conformation. Here we describe a bacteria-based genetic assay that distinguishes cells carrying a model yeast prion protein in its nonprion and prion forms. We then use this assay to investigate the prion-forming potential of single-stranded DNA-binding protein (SSB) of Campylobacter hominis. Our findings indicate that SSB possesses a prion-forming domain that can transition between nonprion and prion conformations. Furthermore, we show that bacterial cells can propagate the prion form over 100 generations in a manner that depends on the disaggregase ClpB. The bacteria-based genetic tool we present may facilitate the investigation of prion-like phenomena in all domains of life.

Prions are infectious, self-propagating protein aggregates that were first described in mammals (1), where they are the causative agent of a group of devastating neurodegenerative diseases known as the transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (2, 3). Prions have also been uncovered in budding yeast and other fungi, where they function as non-Mendelian, protein-based genetic elements that can confer new phenotypes on those cells that harbor them (4–7). Moreover, accumulating evidence suggests that prion-like phenomena play roles in normal biological processes in diverse organisms, including humans (7).

A defining property of prion-forming proteins is their ability to exist in alternative conformational states, at least one of which, the prion form, is self-perpetuating (8–11). Typically, prion-forming proteins adopt an amyloid fold in their prion conformations, thus forming fibrillar aggregates (6, 10). This ability to interconvert between forms commonly depends on a distinct prion domain (PrD) that can often function as a transferable prion-forming module (12–14).

The widespread existence of prion-forming proteins across the fungal kingdom (6, 15–17), together with the demonstration that bacterial cells could propagate a model yeast prion (18), motivated a search for bacterial prions. Relying on a bioinformatic approach to mine bacterial genomes for proteins with candidate PrDs (cPrDs), we identified a protein from Clostridium botulinum, the transcription termination factor Rho, which formed a prion in Escherichia coli cells (19).

It is not yet known how widespread prion-like phenomena are in bacteria, and to what extent such phenomena might represent epigenetic sources of phenotypic diversity in these organisms. Efforts to address these questions have been hampered by a lack of genetic tools to detect prion-like conversion events. Here we describe a transcription-based reporter that distinguishes between E. coli cells that carry a model eukaryotic prion-forming protein in its prion and nonprion forms. We further demonstrate the utility of this assay by investigating the prion-forming potential of a bacterial cPrD, that of single-stranded DNA-binding protein (SSB) from Campylobacter hominis (Ch). We find that the Ch SSB cPrD can convert to a self-propagating prion conformation in E. coli cells, and we use our genetic reporter to show that the cells can propagate the prion for more than 100 generations.

Results

Experimental Strategy.

In previous work with E. coli cells containing the yeast PrD Sup35 NM (where NM designates the transferable prion-forming module of the yeast Sup35 protein), we found that ClpB levels were elevated in cells that harbored Sup35 NM in the aggregated prion conformation compared with cells that contained soluble Sup35 NM (18). Taking advantage of this observation, we sought to develop a genetic assay that could report on prion propagation. Specifically, we fused the clpB promoter (PclpB) to the lacZ gene, creating reporter PclpB–lacZ, and asked whether propagation of the Sup35 NM prion in E. coli cells containing this reporter resulted in increased lacZ expression.

Informing the design of our experiment was the fact that initial formation of the Sup35 NM prion and its propagation are separable events. Whereas the spontaneous conversion of Sup35 NM to its prion form in both yeast and E. coli depends on the presence of a preexisting prion known as [PIN+] (13, 18, 20, 21), once formed, the Sup35 NM prion can be propagated in the absence of [PIN+] (18, 22). Therefore, by providing [PIN+] transiently, we could investigate the ability of the PclpB–lacZ fusion to report specifically on the stable propagation of the Sup35 NM prion. We note that the mechanistic basis for the effect of [PIN+] on acquisition of the Sup35 prion is still uncertain (23).

We previously demonstrated that the yeast New1 protein can serve as [PIN+] in E. coli cells, enabling formation of the Sup35 NM prion, and that a subset of the cells can then propagate the Sup35 NM prion in the absence of New1 (18). Accordingly, for our experiment, we provided the reporter strain cells with compatible plasmids directing the inducible synthesis of both Sup35 NM (fused to mYFP) and New1 (fused to mCFP) to induce formation of the Sup35 NM prion (in cells of the “starter culture”). Furthermore, the New1 plasmid (pSC101TS-NEW1) bore a temperature-sensitive origin of replication, so that the cells could be cured of New1-encoding DNA after a temperature shift to commence the propagation phase of the experiment.

PclpB–lacZ Fusion Reports on the Presence of Sup35 NM Prion Aggregates in E. coli Cells.

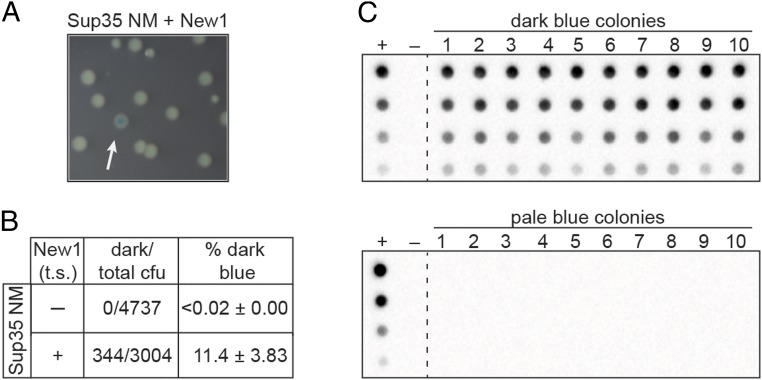

To test whether or not our PclpB–lacZ reporter could be used to distinguish clones of E. coli cells propagating the Sup35 NM prion from those that contained Sup35 NM in its nonprion form, we first prepared starter cultures of cells containing the PclpB–lacZ reporter on an F′ episome, the Sup35 NM plasmid and either the New1 plasmid (experimental sample) or an empty vector (control sample). These starter cultures were grown overnight at the permissive temperature, allowing for the formation of the Sup35 NM prion in the experimental sample. Consistent with our previous work (18), we detected SDS-stable Sup35 NM aggregates only in cells also producing the New1 fusion protein. The cells from both the experimental and the control samples were then plated on appropriate indicator medium and grown at the nonpermissive temperature to cure the cells of either pSC101TS-NEW1 or pSC101TS-empty. The control sample gave rise to colonies that were uniformly pale blue, whereas the experimental sample gave rise to both pale blue colonies and dark blue colonies (∼11% of colonies; Fig. 1 A and B).

Fig. 1.

PclpB–lacZ fusion reports on the presence of the Sup35 NM prion in E. coli cells. (A) Colonies formed by an experimental sample starter culture of PclpB–lacZ reporter strain cells containing Sup35 NM and New1 fusion proteins. After overnight growth at the permissive temperature, the starter culture cells were plated on indicator medium and grown at a temperature nonpermissive for pSC101TS-NEW1 replication. Colonies were photographed after ∼24 h of growth. The white arrow indicates a dark blue colony among pale blue colonies. (B) Dark blue colony counts, total colony forming units (cfu), and the corresponding dark blue colony frequencies (percentage dark blue) are reported for colonies generated from plating the indicated starter cultures. Starter cultures contained the Sup35 NM plasmid and either the New1 temperature sensitive (t.s.) plasmid (+) or the corresponding empty vector (−). The percentage values reflect the sample-size weighted mean of six independent experiments. The SEM of all experiments is reported for each starter culture type. (C) SDS-stable Sup35 NM aggregates are detected by a filter retention assay in cell extracts from 10 of 10 cultures inoculated with dark blue colonies (Top) and 0 of 10 cultures inoculated with pale colonies (Bottom). All colonies were derived from the Sup35 NM + New1 experimental sample starter culture. For each sample, cell extracts were serially diluted threefold. The experimental sample starter culture (Sup35 NM + New1) serves as the positive control (+), whereas the control sample starter culture (Sup35 NM + empty vector) serves as the negative control (−). The α-His antibody recognizes the Sup35 NM-mYFP-His6x fusion protein. See also SI Appendix, Fig. S1. This analysis was performed for two additional experiments (including a total of 24 dark blue colonies and 24 pale blue colonies), and the same correlation between colony color phenotype and the presence or absence of aggregates was observed.

To test whether or not the dark blue colony color is indicative of the presence of prion-like Sup35 NM aggregates, we picked 10 dark blue colonies and 10 pale blue colonies from the experimental sample, inoculated them into liquid medium for overnight growth, and assayed cell extracts for the presence of SDS-stable Sup35 NM aggregates. At the same time, we patched each of the colonies onto selective medium to test for the loss of the New1 plasmid. All 20 colonies had lost the New1 plasmid, as expected, and the absence of New1 protein was confirmed by Western blot analysis (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). We detected SDS-stable Sup35 NM aggregates in all 10 of the dark blue colony samples, but not in any of the pale blue colony samples (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, Western blot analysis revealed that the failure to detect Sup35 NM aggregates in the pale blue colony samples did not reflect a lack of Sup35 NM protein (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). We conclude that the dark blue colony color is a reliable proxy for the presence of Sup35 NM in the aggregated prion conformation.

PclpB–lacZ Reporter Assay Detects Presence of Prion-Like Aggregates Formed by Candidate Prion-Forming Protein from Campylobacter hominis.

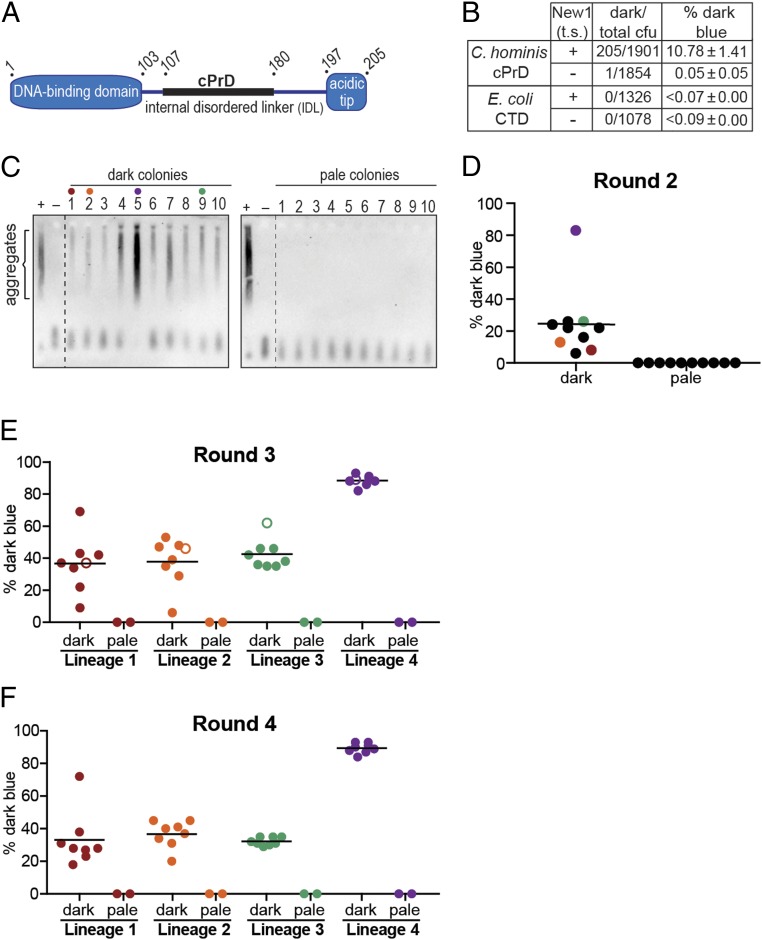

Having demonstrated that our PclpB–lacZ reporter assay could distinguish cells containing Sup35 NM in its soluble, nonprion conformation from cells containing Sup35 NM in its aggregated, prion conformation, we sought to use the assay to evaluate the prion-forming capacity of a candidate bacterial prion-forming protein. We previously performed a computational screen for bacterial proteins containing cPrDs (19) and prioritized high-scoring hits that corresponded to conserved proteins whose functions and domain structures are well characterized. Among these, we identified a number of single-stranded DNA-binding proteins (SSBs) from different bacterial species. SSB family members in bacteria have a conserved domain organization typically consisting of an N-terminal DNA-binding domain, an internal disordered linker, and a small C-terminal acidic tip (Fig. 2A) (24, 25). Each of the SSBs we identified contained a cPrD within the internal disordered linker; we note that many prion-forming proteins appear to have regions of intrinsic disorder (7). We focused in particular on an SSB from Ch because its cPrD (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A) formed intracellular aggregates more robustly than did other SSB cPrDs that we tested.

Fig. 2.

PclpB–lacZ reporter detects the presence of prion-like aggregates formed by Campylobacter hominis SSB cPrD. (A) Schematic of C. hominis SSB domain organization. The candidate prion domain (cPrD) is shown as a black rectangle. See also SI Appendix, Fig. S2A. (B) Dark blue colony counts, total colony-forming units (cfu), and the corresponding dark blue colony frequencies (percentage dark blue) are reported for round 1 (R1) colonies generated from plating the indicated starter cultures. Starter cultures contained either the Ch SSB cPrD plasmid or the E. coli SSB C-terminal domain (CTD) plasmid and either the New1 temperature-sensitive (t.s.) plasmid (+) or the corresponding empty vector (−). The percentage values reflect the sample-size weighted mean of at least four independent experiments. The SEM of all experiments is reported for each starter culture type. (C) SDS-stable Ch SSB cPrD aggregates are detected by SDD-AGE analysis in cell extracts from 10 of 10 cultures inoculated with dark blue R1 colonies (Left) and 0 of 10 cultures inoculated with pale blue R1 colonies (Right). All colonies were derived from the Ch SSB cPrD + New1 starter culture. For each blot, cell extract from the Ch SSB cPrD + New1 starter culture serves as a positive control (+), and cell extract from the Ch SSB cPrD + empty vector starter culture serves as a negative control (−). The α-His antibody recognizes the His6x–mYFP–Ch SSB cPrD fusion protein. The red, orange, green, and purple dots indicate the R1 colonies retrospectively selected as the founders of lineages 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. (D) The frequency of dark blue colonies in round 2 (R2) is shown. Ten dark blue and 10 pale blue R1 colonies were individually resuspended and replated to generate 20 sets of R2 colonies. The frequency of dark blue colonies in each R2 set was estimated by counting and noting the color of at least 100 colonies within each set. Each dot on the scatter plot represents the frequency of dark blue colonies for an individual R2 set. The black bar indicates the average of frequencies across the 10 R2 sets derived from replated dark blue R1 colonies. The red, orange, green, and purple dots indicate the sets selected as lineages 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively, from which eight dark blue and two pale blue colonies were selected and replated to generate round 3 colony sets. (E) The frequency of dark blue colonies in round 3 (R3) is shown. Eight dark blue and two pale blue R2 colonies from each of the four lineage were individually resuspended and replated to generate 40 R3 colony sets. As in R2, at least 100 colonies were counted within each set to estimate the frequency of dark blue colonies (represented by individual color-coded dots on the scatter plot: lineage 1, red; lineage 2, orange; lineage 3, green; and lineage 4, purple). The black bar indicates the average frequency across the 8 R3 sets within a lineage that were derived from replated dark blue R2 colonies. The open circle within each linage indicates the round 3 set from which eight dark blue and two pale blue colonies were selected and replated to generate round 4 colonies for each lineage. (F) The frequency of dark blue colonies in round 4 (R4) is shown. As in R3, eight dark blue and two pale blue R3 colonies from each of the four lineages were individually resuspended and replated to generate 40 R4 colony sets. As in the previous rounds of replating, at least 100 colonies were counted within each set to estimate the frequency of dark blue colonies (represented by individual color-coded dots on the scatter plot: lineage 1, red; lineage 2, orange; lineage 3, green; and lineage 4, purple). The black bar indicates the average frequency across the 8 R4 sets within a lineage that were derived from replated dark blue R3 colonies. The frequency of spontaneous loss of the SSB cPrD prion is estimated to be ≤0.7% per cell per generation for the high-propagation lineage, and ≤2.6% per cell per generation for the low-propagation lineages. These values were calculated by dividing the average percentage pale blue progeny colonies generated from a replated dark blue parent colony by the number of cell divisions required to generate a colony (26). We note that these estimates do not take into account the clonal expansion of pale progeny cells that arise during colony growth, but rather assume that each pale progeny cell arose from an independent spontaneous loss event. Therefore, these values are likely to be significant overestimates of the frequency of spontaneous loss. See also SI Appendix, Figs. S2 B and C and S3.

As an initial test of the ability of the Ch SSB cPrD to access a prion-like conformation, we provided our reporter strain cells with the same compatible plasmids described above, except that we replaced the Sup35 NM-mYFP fusion on the first plasmid with a mYFP-Ch SSB cPrD fusion. After growing the cells overnight at the permissive temperature under inducing conditions, we assayed cell extracts for the presence of SDS-stable Ch SSB cPrD aggregates. We detected Ch SSB cPrD aggregates in extract derived from the cells containing both the Ch SSB cPrD and New1, but not in extract derived from cells containing the Ch SSB cPrD and the corresponding empty vector (Fig. 2C).

The New1 dependence of Ch SSB cPrD aggregate formation under these experimental conditions enabled us to ask whether or not our PclpB–lacZ reporter could reveal a mixed population of cells containing or lacking prion-like (heritable) Ch SSB cPrD aggregates. To do this, we plated overnight cultures containing or lacking Ch SSB cPrD aggregates at the nonpermissive temperature (thereby depriving the aggregate-positive cells of New1) on appropriate indicator medium. Aggregate-positive cultures gave rise to both pale blue colonies and dark blue colonies (∼11% of colonies), whereas aggregate-negative cultures gave rise to pale blue colonies almost exclusively (Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). As a negative control, we performed a parallel set of experiments with an otherwise identical mYFP fusion protein containing the C-terminal domain from E. coli SSB, which lacks a cPrD. When cells producing this fusion protein were plated at the nonpermissive temperature, no dark blue colonies were detected regardless of whether or not the starter culture contained New1 (Fig. 2B).

Proceeding as we did in our proof-of-principle experiments with Sup35 NM, we tested whether or not the dark blue colony color is indicative of the presence of prion-like aggregates. Accordingly, we picked 10 dark blue colonies and 10 pale blue colonies (all derived from the aggregate-positive starter culture), inoculated them into liquid medium for overnight growth, and assayed cell extracts for the presence of SDS-stable Ch SSB cPrD aggregates by using a gel-based assay (semidenaturing detergent agarose gel electrophoresis; SDD-AGE) that permits the visualization of both SDS-stable aggregates and SDS-soluble material (26). We detected SDS-stable Ch SSB cPrD aggregates in all 10 of the dark blue colony samples, but not in any of the pale blue colony samples (Fig. 2C). Western blot analysis revealed that the intracellular Ch SSB cPrD fusion protein levels were comparable among the 20 samples, and all 20 samples were confirmed to have lost the New1 plasmid (by patching on selective medium) and to be devoid of New1 protein (by Western analysis; SI Appendix, Fig. S2B).

These findings demonstrate that the Ch SSB cPrD can access alternative conformations, a soluble nonprion conformation and an aggregated prion-like conformation, and that our PclpB–lacZ reporter reliably distinguishes clones based on these alternative protein conformations. Moreover, the distinguishable colony-color phenotypes indicate that the aggregates are heritable and can be propagated under conditions that do not permit their de novo formation (i.e., in the absence of New1). To further investigate this heritability, we asked whether or not the blue colony-color phenotype and the aggregated conformation of the Ch SSB cPrD could be propagated for additional rounds of plating. Proceeding with the 10 dark blue colonies and the 10 pale blue colonies selected from the first round of plating (designated R1 colonies), we resuspended each colony and plated each suspension to generate sets of round 2 (R2) colonies. Each of the 10 pale blue R1 colonies gave rise to pale R2 colonies exclusively (Fig. 2D). Among the 10 dark blue R1 colonies, 9 gave rise to dark blue R2 colonies at frequencies ranging from 6 to 26%, whereas one gave rise to dark blue R2 colonies at a frequency of 83% (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, these differences in frequency reflected similar differences in the amount of aggregated material present in the corresponding cell extracts (Fig. 2C).

To assess the stability of the blue colony-color phenotypes through additional rounds of plating, we retrospectively selected four of the dark blue R1 clones (Fig. 2D, clones 1, 2, 5, and 9) to establish four independent lineages. For each of the four lineages, we selected eight dark blue R2 colonies and two pale blue R2 colonies. The selected clones were used to inoculate overnight cultures, which were assayed for SDS-stable aggregates (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B), and in parallel, each clone was replated to generate R3 colonies (Fig. 2E). Similarly, we generated R4 colonies (Fig. 2F) for each of the four lineages by selecting eight dark blue R3 colonies and two pale blue R3 colonies (derived from a representative R2 clone from each of the four lineages), which were also analyzed for SDS-stable aggregates (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B). Whereas the selected dark blue colonies gave rise to mixtures of dark blue and pale blue colonies at each successive round of plating (see below), the selected pale blue negative control colonies gave rise exclusively to pale blue colonies (Fig. 2 E and F). Furthermore, the results of the SDD-AGE analysis mirrored the corresponding colony-color phenotypes, with aggregate-positive samples arising exclusively from dark blue colonies selected at each round of plating (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B).

Strikingly, each of the four lineages exhibited consistent behavior through all rounds of plating (Fig. 2 D–F). That is, the dark blue colonies from lineage 4 exhibited a consistent high-propagation phenotype, giving rise to dark blue colonies at frequencies of ≥82% in each round; in contrast, the dark blue colonies from lineages 1–3 gave rise to dark blue colonies at average frequencies of 32–42%. An independent experiment (SI Appendix, Fig. S3) revealed these same behaviors, with two of the four lineages exhibiting the high-propagation frequency phenotype and two exhibiting the lower-propagation phenotype (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 B–D). Despite the largely consistent behavior exhibited by representatives of any given lineage, our analysis revealed one example of apparent conversion from the lower-propagation to the high-propagation phenotype. Specifically, lineage 1 from the first experiment yielded one clone in eight at both R2 and R3 that gave rise to dark blue colonies at a high frequency in the subsequent round of plating (70% and 72%, respectively; Fig. 2 E and F). To investigate the stability of this phenotypic switch within lineage 1, we picked and replated eight dark blue R4 colonies and two pale blue R4 colonies from the set that gave dark blue colonies at a frequency of 72%. Seven of the eight selected dark blue colonies gave rise to dark blue R5 colonies at frequencies of >90%, whereas one gave rise to 34% dark blue R5 colonies, having apparently reverted to the low-propagation phenotype (SI Appendix, Fig. S2C).

Based on our analysis of the progeny of four lineages in each of two independent experiments, we conclude that the Ch SSB cPrD can access an aggregated prion-like conformation that can be propagated over at least 100 generations (∼104 generations for R4 colonies and ∼130 generations for R5 colonies; see SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods).

ClpB Is Required for the Propagation of Ch SSB cPrD Aggregates.

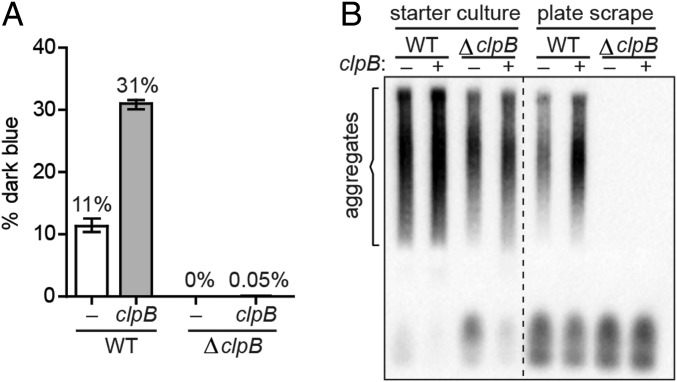

The propagation of the Sup35 prion and other prions in yeast depends on the ATP-dependent disaggregase Hsp104, which functions to fragment prion aggregates into smaller seeds that initiate new rounds of propagation, helping to ensure that prion particles are efficiently partitioned to daughter cells during cell division (7, 10). Similarly, the propagation of the Sup35 NM prion in E. coli cells depends on the Hsp104 ortholog ClpB (18). To investigate whether or not the propagation of Ch SSB cPrD aggregates depends on ClpB, we used a previously described strategy to deplete reporter strain cells of ClpB specifically during the propagation phase of the experiment (18). Specifically, we used a version of our New1 plasmid that also directed the synthesis of ClpB under the control of its native promoter (pSC101TS-NEW1-clpB). By introducing the Ch SSB cPrD plasmid together with pSC101TS-NEW1-clpB into a ΔclpB derivative of our reporter strain, we could grow starter cultures containing ClpB, and subsequently deprive cells of both New1 and ClpB by plating at the nonpermissive temperature.

For this experiment, we transformed both clpB+ and ΔclpB reporter strain cells with the Ch SSB cPrD plasmid and either pSC101TS-NEW1 or pSC101TS-NEW1-clpB. When the positive control clpB+ starter culture cells were plated at the nonpermissive temperature, we obtained both dark blue and pale blue R1 colonies, as expected (Fig. 3A); interestingly, the presence of plasmid-encoded ClpB in the starter culture resulted in an ∼threefold increase in the fraction of dark blue colonies (Fig. 3A), raising the possibility that the wild-type level of ClpB during starter culture growth is limiting for the formation of aggregate-positive colonies. In contrast, when the ΔclpB starter culture cells were plated at the nonpermissive temperature, we obtained almost exclusively pale blue R1 colonies (with just one exception), regardless of whether the starter cultures contained plasmid-encoded ClpB or not (Fig. 3A). The results of SDD-AGE analysis were consistent with these findings. All starter cultures (clpB+ and ΔclpB) contained SDS-stable Ch SSB cPrD aggregates (Fig. 3B). However, only clpB+ starter cultures gave rise to R1 colonies containing SDS-stable aggregates (detected in cell extracts prepared from pooled colonies scraped from R1 plates; Fig. 3B and SI Appendix, Fig. S4). We conclude that ClpB is required for the propagation of Ch SSB cPrD prion-like aggregates, mirroring the requirement of ClpB for the propagation of Sup35 NM aggregates in E. coli cells (18) and the requirement of Hsp104 for the propagation of Sup35 aggregates in yeast (10).

Fig. 3.

ClpB is required for propagation of Ch SSB cPrD aggregates. (A) The frequency of dark blue colonies generated from plating the indicated clpB+ and ΔclpB starter cultures is shown. All starter cultures contained the Ch SSB cPrD vector, and either pSC101TS–NEW1 (white bars) or pSC101TS–NEW1–clpB (gray bars). After overnight growth at the permissive temperature, cultures were plated at a nonpermissive temperature to cure cells of pSC101TS–NEW1 or pSC101TS–NEW1–clpB. The sample-size weighted mean percentage of dark blue colonies from three independent experiments is shown with error bars indicating the SEM. (B) Colonies were generated by plating the indicated starter cultures at a temperature nonpermissive for pSC101TS–NEW1 or pSC101TS–NEW1–clpB replication. Cell extracts were prepared by pooling and lysing ∼700 scraped colonies for each starter culture from a single experiment. SDS-stable aggregates of Ch SSB cPrD fusion protein are not detected in ΔclpB colony scrapes, regardless of whether or not clpB was supplied during starter culture growth. The α-His antibody recognizes the His6x–mYFP–Ch SSB cPrD fusion protein. See also SI Appendix, Fig. S4.

Discussion

We have developed a transcription-based reporter in E. coli that distinguishes between cells that harbor specific prion-forming proteins in their nonprion and their aggregated prion conformations. Specifically, we found that a PclpB–lacZ reporter responded to the presence of prion-like aggregates in the cell. Having shown that our assay distinguished between cells that contain the model yeast prion-forming protein Sup35 NM in its nonprion and prion forms, we used the same reporter-containing cells to demonstrate that a bioinformatically identified candidate PrD, the Ch SSB cPrD, accessed a self-propagating prion conformation in E. coli cells. Moreover, we found that E. coli cells could propagate this prion for over 100 generations, and that this propagation depended strictly on the presence of the disaggregase ClpB.

Colony-Color Heterogeneity as a Manifestation of Prion-Like Conversion Events.

The defining characteristic of prion-forming proteins is their ability to transition between alternative conformational states, one of which, the prion form, is self-propagating (7, 8, 10). Our assay enables the identification of these two alternative states based on a readily detectable colony-color phenotype. Moreover, it provides a facile means to assess the stability of the prion state, enabling a determination of the frequency of prion loss (see Fig. 2 legend). Although our reporter is likely to respond to the presence of various types of protein aggregates, we can readily distinguish between aggregation-prone proteins and prion-like phenomena on the basis of the appearance of alternative colony-color phenotypes that manifest under identical growth conditions.

PclpB Promoter Activity and Proteostatic Stress.

The increase in PclpB promoter activity in cells containing prion-like aggregates, and Sup35 NM aggregates in particular, is consistent with prior work in which we implicated the chaperone DnaK in remodeling Sup35 NM aggregates in E. coli cells (18). This follows because clpB is expressed under the control of the heat shock sigma factor σ32, whose activity is controlled by DnaK. Thus, DnaK interacts directly with σ32, inhibiting its activity and facilitating its degradation in the absence of stress-induced protein unfolding (27). However, the presence of protein substrates that compete with σ32 for DnaK binding (e.g., Sup35 NM aggregates) leads to increased σ32 activity and the up-regulation of σ32-dependent gene expression (28). Whether or not DnaK may be blind to certain prion-like aggregates, precluding the use of our PclpB–lacZ reporter for their detection, remains to be learned. In particular, both Sup35 and Ch SSB have PrDs that are rich in asparagines and glutamines (14), and we do not know whether the system can report on the presence of prion-like aggregates formed by proteins that do not share this characteristic. Furthermore, we presume that protein aggregates of interest must be present in sufficient quantity so that they can effectively titrate DnaK (which is a relatively abundant protein). We note also that a recently described class of nonamyloid prions, with structural characteristics that have not yet been defined, may or may not be detectable with our reporter (29).

The Ch SSB cPrD Adopts High-Propagation and Low-Propagation Prion States.

In examining the propagation of the Ch SSB cPrD prion, we observed two distinct behaviors. Among eight lineages that we followed (four in each of two independent experiments), three propagated the prion at high average frequencies of ≥80%, whereas five propagated the prion at average frequencies ranging between 27% and 48%. We speculate that the Ch SSB cPrD can access distinct prion-like conformations, a phenomenon that has been documented among both mammalian and fungal prion-forming proteins (30–32). Such distinct prion conformations are referred to as strains; that is, prions formed by identical proteins that nonetheless exhibit phenotypically distinguishable transmissible states that correspond to distinct amyloid conformations (33–36). Whether or not the high- and low-propagation phenotypes associated with the Ch SSB cPrD similarly correspond to distinct amyloid conformations remains to be investigated.

A Second Prion-Forming Protein in Bacteria.

Our findings with the cPrD of Ch SSB expand the repertoire of putative prion-forming proteins in bacteria. In prior work, we showed that the transcription termination factor Rho from Clostridium botulinum formed a prion in E. coli cells, with the concomitant loss of Rho activity eliciting genome-wide changes in the transcriptome (19). The demonstration that the cPrD of Ch SSB can function as a transferable prion-forming module suggests that Ch SSB likewise has prion-forming potential, providing additional support for the hypothesis that protein-based heredity can serve as a source of phenotypic diversity in the bacterial domain of life. SSB is conserved in bacteria (37) and plays critical roles in DNA replication, recombination, and repair, interacting with numerous other players in these processes (24). We do not know what the physiologic consequences of SSB prion formation in C. hominis might be. One possibility is that SSB prion formation might confer resistance to infection by a phage that depends on the host-encoded SSB for its replication cycle. As an example, phage N4, which infects E. coli, is strictly dependent on the bacterially encoded SSB for its early gene transcription (38); furthermore, although ssb is an essential gene, cells carrying a reduced-function ssb allele are viable but unable to support N4 replication (38).

Conclusion.

Our findings validate a simple bacteria-based genetic tool with the potential to greatly facilitate the evaluation and study of candidate prion-forming proteins from bacteria and other organisms, providing a complement to both classical and recently described yeast-based genetic assays (13, 14, 39, 40).

Materials and Methods

For details about strains, plasmid construction, PclpB–lacZ reporter construction, and experimental methods, see SI Appendix. Starter cultures were generated by inducing production of Sup35 NM or Ch SSB cPrD fusion proteins overnight, with or without simultaneous induction of the New1 fusion protein. The plate assay was performed by plating these starter cultures on indicator medium at the nonpermissive temperature to cure cells of the New1 plasmid. The resulting dark blue and pale blue colonies were screened for SDS-stable aggregates of Sup35 NM or Ch SSB cPrD fusion proteins by a filter retention assay or SDS-semidenaturing gel electrophoresis (SI Appendix). The Ch SSB cPrD propagation experiment was performed by serially passaging Ch SSB cPrD containing dark blue colonies on indicator medium for ∼100 generations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank S. R. Goldman for technical suggestions, S. L. Dove for invaluable discussion and critical reading of the manuscript, S. J. Garrity for critical reading of the manuscript, and T. G. Bernhardt for generous gift of antibody. Work was supported by Grant GM115941 (to A.H.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1817711116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Prusiner SB. Novel proteinaceous infectious particles cause scrapie. Science. 1982;216:136–144. doi: 10.1126/science.6801762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguzzi A, Calella AM. Prions: Protein aggregation and infectious diseases. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:1105–1152. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00006.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aguzzi A, Lakkaraju AKK. Cell biology of prions and prionoids: A status report. Trends Cell Biol. 2016;26:40–51. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wickner RB. [URE3] as an altered URE2 protein: Evidence for a prion analog in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science. 1994;264:566–569. doi: 10.1126/science.7909170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halfmann R, et al. Prions are a common mechanism for phenotypic inheritance in wild yeasts. Nature. 2012;482:363–368. doi: 10.1038/nature10875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Newby GA, Lindquist S. Blessings in disguise: Biological benefits of prion-like mechanisms. Trends Cell Biol. 2013;23:251–259. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chakravarty AK, Jarosz DF. More than just a phase: Prions at the crossroads of epigenetic inheritance and evolutionary change. J Mol Biol. 2018;430:4607–4618. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2018.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chien P, Weissman JS, DePace AH. Emerging principles of conformation-based prion inheritance. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:617–656. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tuite MF, Marchante R, Kushnirov V. Fungal prions: Structure, function and propagation. Top Curr Chem. 2011;305:257–298. doi: 10.1007/128_2011_172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liebman SW, Chernoff YO. Prions in yeast. Genetics. 2012;191:1041–1072. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.137760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harvey ZH, Chen Y, Jarosz DF. Protein-based inheritance: Epigenetics beyond the chromosome. Mol Cell. 2018;69:195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li L, Lindquist S. Creating a protein-based element of inheritance. Science. 2000;287:661–664. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5453.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osherovich LZ, Weissman JS. Multiple Gln/Asn-rich prion domains confer susceptibility to induction of the yeast [PSI(+)] prion. Cell. 2001;106:183–194. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00440-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alberti S, Halfmann R, King O, Kapila A, Lindquist S. A systematic survey identifies prions and illuminates sequence features of prionogenic proteins. Cell. 2009;137:146–158. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coustou V, Deleu C, Saupe S, Begueret J. The protein product of the het-s heterokaryon incompatibility gene of the fungus Podospora anserina behaves as a prion analog. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9773–9778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santoso A, Chien P, Osherovich LZ, Weissman JS. Molecular basis of a yeast prion species barrier. Cell. 2000;100:277–288. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81565-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saupe SJ. The [Het-s] prion of Podospora anserina and its role in heterokaryon incompatibility. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2011;22:460–468. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yuan AH, Garrity SJ, Nako E, Hochschild A. Prion propagation can occur in a prokaryote and requires the ClpB chaperone. eLife. 2014;3:e02949. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuan AH, Hochschild A. A bacterial global regulator forms a prion. Science. 2017;355:198–201. doi: 10.1126/science.aai7776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Derkatch IL, Bradley ME, Zhou P, Chernoff YO, Liebman SW. Genetic and environmental factors affecting the de novo appearance of the [PSI+] prion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1997;147:507–519. doi: 10.1093/genetics/147.2.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Derkatch IL, Bradley ME, Hong JY, Liebman SW. Prions affect the appearance of other prions: The story of [PIN(+)] Cell. 2001;106:171–182. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00427-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Derkatch IL, et al. Dependence and independence of [PSI(+)] and [PIN(+)]: A two-prion system in yeast? EMBO J. 2000;19:1942–1952. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.9.1942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Serio TR. [PIN+]ing down the mechanism of prion appearance. FEMS Yeast Res. 2018;18 doi: 10.1093/femsyr/foy026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shereda RD, Kozlov AG, Lohman TM, Cox MM, Keck JL. SSB as an organizer/mobilizer of genome maintenance complexes. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;43:289–318. doi: 10.1080/10409230802341296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bianco PR. The tale of SSB. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2017;127:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bagriantsev SN, Kushnirov VV, Liebman SW. Analysis of amyloid aggregates using agarose gel electrophoresis. Methods Enzymol. 2006;412:33–48. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)12003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gamer J, et al. A cycle of binding and release of the DnaK, DnaJ and GrpE chaperones regulates activity of the Escherichia coli heat shock transcription factor sigma32. EMBO J. 1996;15:607–617. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guo MS, Gross CA. Stress-induced remodeling of the bacterial proteome. Curr Biol. 2014;24:R424–R434. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chakrabortee S, et al. Intrinsically disordered proteins drive emergence and inheritance of biological traits. Cell. 2016;167:369–381. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Collinge J, Clarke AR. A general model of prion strains and their pathogenicity. Science. 2007;318:930–936. doi: 10.1126/science.1138718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tessier PM, Lindquist S. Unraveling infectious structures, strain variants and species barriers for the yeast prion [PSI+] Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:598–605. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tycko R. Amyloid polymorphism: Structural basis and neurobiological relevance. Neuron. 2015;86:632–645. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanaka M, Chien P, Naber N, Cooke R, Weissman JS. Conformational variations in an infectious protein determine prion strain differences. Nature. 2004;428:323–328. doi: 10.1038/nature02392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diaz-Avalos R, King CY, Wall J, Simon M, Caspar DL. Strain-specific morphologies of yeast prion amyloid fibrils. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:10165–10170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504599102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Toyama BH, Kelly MJ, Gross JD, Weissman JS. The structural basis of yeast prion strain variants. Nature. 2007;449:233–237. doi: 10.1038/nature06108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohhashi Y, et al. Molecular basis for diversification of yeast prion strain conformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:2389–2394. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1715483115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tatusov RL, et al. The COG database: New developments in phylogenetic classification of proteins from complete genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:22–28. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Markiewicz P, Malone C, Chase JW, Rothman-Denes LB. Escherichia coli single-stranded DNA-binding protein is a supercoiled template-dependent transcriptional activator of N4 virion RNA polymerase. Genes Dev. 1992;6:2010–2019. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.10.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sondheimer N, Lindquist S. Rnq1: An epigenetic modifier of protein function in yeast. Mol Cell. 2000;5:163–172. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80412-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Newby GA, et al. A genetic tool to track protein aggregates and control prion inheritance. Cell. 2017;171:966–979. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.