Actin is one of the most abundant and highly conserved proteins in nature. The cellular pool of actin is roughly evenly divided between monomeric (G-actin) and filamentous (F-actin) forms, with the dynamic transition between these two states being tightly regulated in time and space (1). Most actin functions are linked to its filamentous form. The atomic structure of the actin monomer in complex with DNase I was determined ∼30 y ago (2) and was used to produce the first model of the filament by fitting the 8.4-Å-resolution X-ray diffraction pattern of oriented gels of actin filaments (3). Today, more than 100 structures of the monomer have been determined. Crystallization has been made possible using one of several strategies that prevent polymerization, including mutagenesis, covalent modification of actin, and the formation of soluble complexes with actin-binding protein (ABPs) or marine toxins. Remarkably, the conformation of the monomer in all these structures is essentially the same. Actin has four subdomains, with subdomains 1 and 3 being structurally related, and subdomains 2 and 4 consisting of large insertions into subdomains 1 and 3. Because of their relative position in the filament, actin is also described as consisting of two major domains, with subdomains 1 and 2 forming the more exposed outer domain and subdomains 3 and 4 forming the inner domain (Fig. 1). Actin has two opposite clefts, one between subdomains 2 and 4 that harbors the nucleotide-binding site, and one between subdomains 1 and 3 that mediates most of the interactions with ABPs. The polypeptide chain crosses between the outer and inner domains only twice, at helix Q137-S145 and at loop R335-Y337, such that the nucleotide itself becomes a major bridge between the two domains.

Fig. 1.

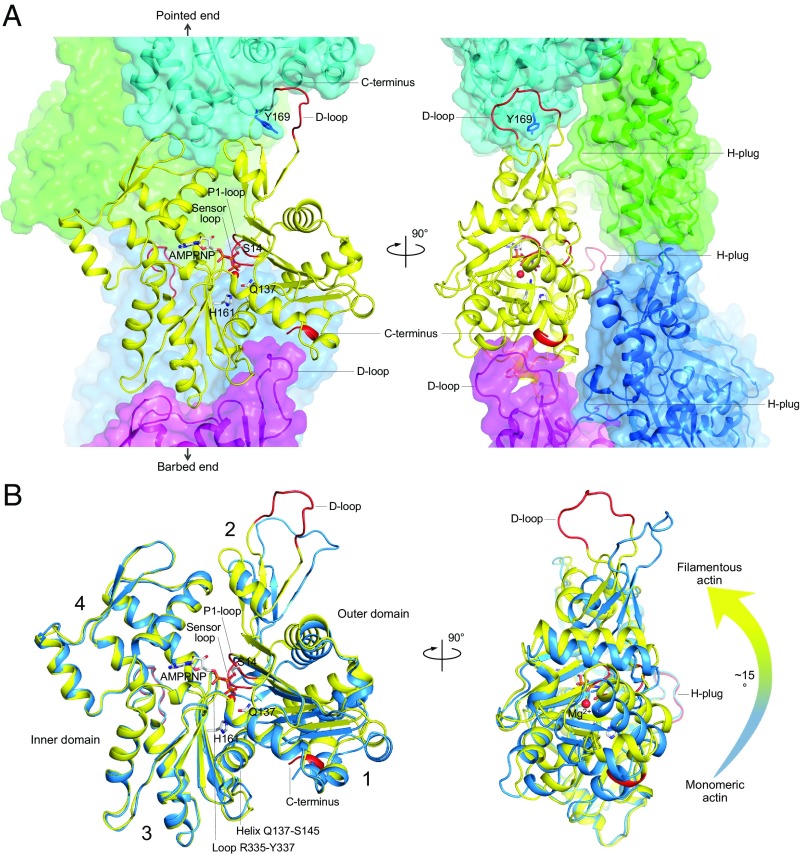

Structure of the actin filament in the AMPPNP-bound state (23). (A) Orthogonal views of the cryo-EM structure of the filament with bound AMPPNP determined at 3.1 Å resolution [Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID code 6DJM]. One subunit in the filament (yellow) interacts with four other subunits: two along the long-pitch helix (cyan, magenta) and two on the opposite strand (green, blue). The conformational change upon Pi release affects primarily the P1-loop (G13-G15), sensor loop (E72-G74), D-loop (Q41-Q49), and the C terminus (R372-F375), all highlighted red. Interactions along the long-pitch helix are stronger and involve the D-loop, which binds in the hydrophobic- (or target-)binding cleft of the subunit immediately above it, making contacts with both subdomain 1 (C terminus) and subdomain 3 (Y169). Lateral contacts involve primarily the hydrophobic plug (H-plug), which contacts two subunits on the opposite strand, including the D-loop of one of these subunits. (B) Superimposition of a subunit from the AMPPNP-bound filament structure (yellow) with the ATP-bound structure of monomeric actin in complex with a tropomodulin fragment (blue, PDB ID code 4PKG), using the inner domain as reference for fitting (G146-E334). The orientation and highlighted regions (red) are the same as in A. Numbers 1 to 4 indicate the four actin subdomains. The transition from monomeric to filamentous actin involves an ∼15° rotation of the outer domain with respect to the inner domain (arrow on the right), with helix Q137-S145 and loop R335-Y337 acting as a hinge for this rotation. This rotation repositions the side chains of Q137, H161, and the P1-loop for ATP hydrolysis.

The original model of the filament was mostly correct; it properly defined the orientation and relative position of subunits with respect to one another. The filament can be described as either two right-handed, long-pitch helices of head-to-tail interacting actin subunits or a single left-handed, short-pitch helix. However, this model lacked the resolution to reveal conformational changes occurring upon polymerization or the exact nature of intersubunit contacts. This is because the monomer structure was fitted into the fiber diffraction pattern with only minor changes. However, a conformational change was anticipated, since it has long been known that ATP hydrolysis occurs immediately upon polymerization, whereas the monomer essentially lacks ATPase activity (4). A second conformational change was expected upon release of the γ-phosphate (Pi), which occurs slowly after hydrolysis and acts as a molecular timer to control depolymerization and the interactions of several ABPs (1, 4). Thus, cofilin, which accelerates depolymerization by inducing a twist in the filament that creates fragile boundaries at the interface between bare and cofilin-decorated segments (5, 6), binds preferentially to ADP-actin (7). Myosin also seems to sense nucleotide state-dependent differences in the filament. Thus, myosin-5 and myosin-6, which travel in opposite directions along actin filaments, take longer runs on ADP-Pi (younger) and ADP (older) filaments, respectively (8). Newly assembled, ADP-Pi filaments are also more rigid than older, ADP-actin filaments, with persistence lengths of 13.5 and 9 μM, respectively (9). Consistent with these observations, studies using site-specific proteolysis, chemical modification, cysteine cross-linking, and spectroscopic measurements supported the existence of a nucleotide-dependent conformational change, affecting specifically the DNase I-binding loop (D-loop) within subdomain 2 and the C terminus (10–12). Low-resolution structural studies using electron microscopy (EM) also suggested the existence of large nucleotide-dependent (13) and even nucleotide-independent (14) structural changes in the filament, including opening and closing of the nucleotide-binding cleft and movements of the D-loop.

A significant breakthrough in our understanding of the structure of the filament occurred in 2009 when Oda et al. (15) improved the resolution of X-ray fiber diffraction to 3.3 Å and established that actin subunits in the filament adopt a flatter conformation compared with that of the monomer. Subunit flattening was proposed to rearrange the catalytic cleft for hydrolysis, although this could not be directly visualized using model fitting to the fiber diffraction data. A validation of these findings and direct visualization of the structural changes taking place upon polymerization followed in a series of cryo-EM studies of ever-improving resolution, both before and after the advent of direct electron detectors and of the filament alone (16, 17) or bound to ABPs (5, 18–21).

These structures all represented the ADP-bound state of the filament, and thus important questions regarding the catalytically active conformation of actin subunits and the effects of nucleotide hydrolysis and Pi release on the structure of the filament remained unanswered. Two recent studies address these questions, including a study by Merino et al. (22) and a study by Chou and Pollard in PNAS (23). The two groups determine structures of the filament in various nucleotide-bound states using cryo-EM. However, while their structures are similar, the two groups reach somewhat different conclusions, with Merino et al. (22) emphasizing the existence of structurally distinct “open” and “closed” states and Chou and Pollard (23) stressing the close similarity of the structures independent of nucleotide state. The analysis below is based on the structures of Chou and Pollard (23), which are determined at higher resolution thanks to several optimizations during sample preparation to ensure homogeneity of the nucleotide state and bound divalent cation (Mg2+ in this case), as well as during the preparation of cryo-EM grids and data collection, including optimization of the ice thickness, minimization of the tension on filaments during blotting, and the selection of micrographs and filaments for averaging. Importantly, Chou and Pollard (23) do not use phalloidin or any other filament-stabilizing molecule that could impede nucleotide-dependent structural transitions in the filament (9).

The main conclusion from both studies is that the structures of ATP [represented by the slowly hydrolyzed ATP analog β,γ-imidoadenosine 5′-triphosphate (AMPPNP)], ADP-Pi and ADP filamentous actin are nearly identical so that assembly, not hydrolysis, drives the conformational change. This conclusion mirrors the situation with the monomer, in which the structures of ATP- (or AMPPNP-) and ADP-bound actin are nearly identical (24–26). However, the conformation of subunits in the filament is quite different from that of the monomer, with polymerization flattening the actin subunit by a rotation of the outer domain relative to the inner domain using helix Q137-S145 and loop R335-Y337 as a hinge (Fig. 1B). This transition readies the catalytic site for ATP hydrolysis by repositioning the side chains of Q137 and H161 and the P1-loop containing S14, which coordinates the γ-phosphate.

In both the filament and the monomer, the subtle changes occurring upon Pi release are confined to the nucleotide-binding site and the neighboring sensor loop, and these changes seem to impact the stability, albeit less so the structure, of subdomain 2, and specifically the D-loop (Fig. 1). However, in the filament, these minor changes are transmitted from subunit to subunit resulting in cumulative effects that may explain previous biochemical observations (4, 7–12). Intersubunit contacts are stronger along the long-pitch helix of the filament (helical strand) and are more significantly impacted by these structural changes. Chou and Pollard (23) show that the D-loop of one subunit contacts Y169 and the C terminus of the subunit immediately above it, which also changes conformation upon Pi release (Fig. 1A). Intermolecular coupling between the D-loop and the C terminus had been previously noted using fluorescence and proteolytic digestion (27). Interstrand contacts are weaker and primarily involve the hydrophobic plug (Fig. 1A), which fits at the interface between two subunits of the opposite strand, notably making contacts with the D-loop of one of these subunits. In this way, changes in the D-loop occurring upon Pi release also affect the lateral interstrand contacts.

In retrospect, it is not surprising that the structure of the filament changes little among the various nucleotide states, since the filament does not disassemble readily upon Pi release, and proteins such as cofilin are needed to accelerate this step. Chou and Pollard (23) propose that the minor changes in the D-loop, specifically its increased flexibility in the ADP state, can explain the higher affinity of cofilin for this state, since cofilin binding would be sterically incompatible with the stable conformation of the D-loop in the AMPPNP and ADP-Pi structures. Recently, Tanaka et al. (5) showed that cofilin binding to the filament reverts most of the flattening transition occurring upon polymerization, with actin subunits adopting a new conformation that more closely resembles that of the monomer.

Still missing are reliable structures of the pointed and barbed ends of the filament. Chou and Pollard (23) propose that subunits at the barbed end have the same flattened conformation as the rest of the filament, creating a favorable binding interface for incoming monomers. In contrast, free monomers are not flattened and thus lack a favorable binding interface for incorporation at the pointed end, which may explain why the barbed end elongates faster than the pointed end. It is likely, however, that subunits at the pointed end are not flattened, since they are not constrained by interactions of their D-loop and are more likely to contain ADP bound. This would explain why actin structures in complex with tropomodulin, which caps the pointed end in striated muscle (28), display a nonflattened conformation with the D-loop interacting extensively with tropomodulin (29).

Acknowledgments

R.D.’s research is supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 GM073791 and R01 MH087950.

Footnotes

The author declares no conflict of interest.

See companion article on page 4265.

References

- 1.Dominguez R, Holmes KC. Actin structure and function. Annu Rev Biophys. 2011;40:169–186. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-042910-155359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kabsch W, Mannherz HG, Suck D, Pai EF, Holmes KC. Atomic structure of the actin:DNase I complex. Nature. 1990;347:37–44. doi: 10.1038/347037a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holmes KC, Popp D, Gebhard W, Kabsch W. Atomic model of the actin filament. Nature. 1990;347:44–49. doi: 10.1038/347044a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Korn ED, Carlier MF, Pantaloni D. Actin polymerization and ATP hydrolysis. Science. 1987;238:638–644. doi: 10.1126/science.3672117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanaka K, et al. Structural basis for cofilin binding and actin filament disassembly. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1860. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04290-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huehn A, et al. The actin filament twist changes abruptly at boundaries between bare and cofilin-decorated segments. J Biol Chem. 2018;293:5377–5383. doi: 10.1074/jbc.AC118.001843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blanchoin L, Pollard TD. Mechanism of interaction of Acanthamoeba actophorin (ADF/Cofilin) with actin filaments. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:15538–15546. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.22.15538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zimmermann D, Santos A, Kovar DR, Rock RS. Actin age orchestrates myosin-5 and myosin-6 run lengths. Curr Biol. 2015;25:2057–2062. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Isambert H, et al. Flexibility of actin filaments derived from thermal fluctuations. Effect of bound nucleotide, phalloidin, and muscle regulatory proteins. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:11437–11444. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.19.11437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muhlrad A, Cheung P, Phan BC, Miller C, Reisler E. Dynamic properties of actin. Structural changes induced by beryllium fluoride. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:11852–11858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oztug Durer ZA, Diraviyam K, Sept D, Kudryashov DS, Reisler E. F-actin structure destabilization and DNase I binding loop: Fluctuations mutational cross-linking and electron microscopy analysis of loop states and effects on F-actin. J Mol Biol. 2010;395:544–557. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moraczewska J, Wawro B, Seguro K, Strzelecka-Golaszewska H. Divalent cation-, nucleotide-, and polymerization-dependent changes in the conformation of subdomain 2 of actin. Biophys J. 1999;77:373–385. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)76896-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belmont LD, Orlova A, Drubin DG, Egelman EH. A change in actin conformation associated with filament instability after Pi release. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:29–34. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galkin VE, Orlova A, Schröder GF, Egelman EH. Structural polymorphism in F-actin. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:1318–1323. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oda T, Iwasa M, Aihara T, Maéda Y, Narita A. The nature of the globular- to fibrous-actin transition. Nature. 2009;457:441–445. doi: 10.1038/nature07685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujii T, Iwane AH, Yanagida T, Namba K. Direct visualization of secondary structures of F-actin by electron cryomicroscopy. Nature. 2010;467:724–728. doi: 10.1038/nature09372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galkin VE, Orlova A, Vos MR, Schröder GF, Egelman EH. Near-atomic resolution for one state of F-actin. Structure. 2015;23:173–182. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.von der Ecken J, et al. Structure of the F-actin-tropomyosin complex. Nature. 2015;519:114–117. doi: 10.1038/nature14033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.von der Ecken J, Heissler SM, Pathan-Chhatbar S, Manstein DJ, Raunser S. Cryo-EM structure of a human cytoplasmic actomyosin complex at near-atomic resolution. Nature. 2016;534:724–728. doi: 10.1038/nature18295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mentes A, et al. High-resolution cryo-EM structures of actin-bound myosin states reveal the mechanism of myosin force sensing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:1292–1297. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1718316115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iwamoto DV, et al. Structural basis of the filamin A actin-binding domain interaction with F-actin. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2018;25:918–927. doi: 10.1038/s41594-018-0128-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merino F, et al. Structural transitions of F-actin upon ATP hydrolysis at near-atomic resolution revealed by cryo-EM. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2018;25:528–537. doi: 10.1038/s41594-018-0074-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chou SZ, Pollard TD. Mechanism of actin polymerization revealed by cryo-EM structures of actin filaments with three different bound nucleotides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:4265–4274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1807028115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Graceffa P, Dominguez R. Crystal structure of monomeric actin in the ATP state. Structural basis of nucleotide-dependent actin dynamics. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:34172–34180. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303689200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Otterbein LR, Graceffa P, Dominguez R. The crystal structure of uncomplexed actin in the ADP state. Science. 2001;293:708–711. doi: 10.1126/science.1059700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rould MA, Wan Q, Joel PB, Lowey S, Trybus KM. Crystal structures of expressed non-polymerizable monomeric actin in the ADP and ATP states. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:31909–31919. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601973200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim E, Reisler E. Intermolecular coupling between loop 38-52 and the C-terminus in actin filaments. Biophys J. 1996;71:1914–1919. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79390-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fowler VM, Dominguez R. Tropomodulins and leiomodins: Actin pointed end caps and nucleators in muscles. Biophys J. 2017;112:1742–1760. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rao JN, Madasu Y, Dominguez R. Mechanism of actin filament pointed-end capping by tropomodulin. Science. 2014;345:463–467. doi: 10.1126/science.1256159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]