Significance

The nuclear lamina is an integral component of all metazoan cells. While the individual constituents of the nuclear lamina, the A- and B-type lamins, have been well studied, whether they exhibit a distinct spatial organization is unclear. Using stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy, we have identified two organizing principles of the nuclear lamina: lamin B1 forms an outer concentric ring, and its localization is curvature-dependent. This suggests that a role of lamin B1 is to stabilize nuclear shape by restraining outward protrusions of the lamin A/C network. These findings provide a model for the nuclear lamina that can predict its behavior and clarify the distinct functional roles for the individual lamina components and the consequences of their perturbation.

Keywords: nucleus, lamin, bleb, curvature, meshwork

Abstract

The nuclear lamina is an intermediate filament meshwork adjacent to the inner nuclear membrane (INM) that plays a critical role in maintaining nuclear shape and regulating gene expression through chromatin interactions. Studies have demonstrated that A- and B-type lamins, the filamentous proteins that make up the nuclear lamina, form independent but interacting networks. However, whether these lamin subtypes exhibit a distinct spatial organization or whether their organization has any functional consequences is unknown. Using stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM) our studies reveal that lamin B1 and lamin A/C form concentric but overlapping networks, with lamin B1 forming the outer concentric ring located adjacent to the INM. The more peripheral localization of lamin B1 is mediated by its carboxyl-terminal farnesyl group. Lamin B1 localization is also curvature- and strain-dependent, while the localization of lamin A/C is not. We also show that lamin B1’s outer-facing localization stabilizes nuclear shape by restraining outward protrusions of the lamin A/C network. These two findings, that lamin B1 forms an outer concentric ring and that its localization is energy-dependent, are significant as they suggest a distinct model for the nuclear lamina—one that is able to predict its behavior and clarifies the distinct roles of individual nuclear lamin proteins and the consequences of their perturbation.

The nuclear lamina is a meshwork of intermediate filaments that lies beneath the inner nuclear membrane (INM) in all metazoan cells (1). In addition to playing a critical role in regulating the shape and structural integrity of the nuclear envelope, it also has important functions in regulating gene expression through chromatin interactions and integrating cytoskeletal dynamics within the cell (2, 3). Two types of intermediate filament proteins make up the nuclear lamina: A-type lamins, primarily lamin A and lamin C, are coded for by LMNA, while B-type lamins include lamin B1 and lamin B2 and are coded for by LMNB1 and LMNB2, respectively (4–6). The two lamin subtypes also undergo distinct posttranslational modifications, with the B-type lamins retaining the addition of a farnesyl group, while this is not present in A-type lamins (7).

A-type lamin expression is associated with differentiated mesenchymal cells and with stiffer cells and nuclei (8). Mice null for Lmna initially develop normally but succumb to muscular dystrophy and cardiomyopathy after 4–6 wk (9). Alternatively, neurons and glia in the central nervous system have high lamin C expression but little to no lamin A (10). In contrast, B-type lamins are expressed in all cell types throughout development and differentiation and are required for proper organogenesis as well as neuronal migration and patterning during brain development (11, 12). Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) from Lmna-knockout mice demonstrate highly elongated nuclei with the loss of nuclear envelope proteins, including B-type lamins, from one pole (9). In contrast, knockouts of Lmnb1 result in excessive nuclear herniations known as blebs that are highly associated with gene-rich euchromatin (13). Mutations in lamin A result in a wide variety of diseases, collectively termed as laminopathies, that include muscular dystrophies, lipodystrophies, and premature aging phenotypes such as Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS), while mutations in lamin B1 cause the demyelinating disorder autosomal dominant leukodystrophy (14).

Studies utilizing optical microscopy and cryo-electron tomography to visualize the structural organization of lamins in mammalian cells revealed the presence of a meshwork structure and indicated that each component formed separate but interacting meshworks (13, 15, 16). However, no distinct spatial organization of the individual lamin subtypes across the nuclear envelope was reported.

Here, we used stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM) and quantitative image analysis to examine the spatial localization of lamin A/C and lamin B1 at the nuclear periphery. We have found that farnesylated lamin B1 forms an outer rim within the nuclear lamina, preferentially localizing closest to the INM, while the lamin A/C meshwork faces the nucleoplasm with significant overlap between the two networks. Additionally, A-type lamins form tightly spaced structures juxtaposed by the loosely spaced, deformable lamin B1 filament network. We also show that the localization of lamin B1 is dependent upon the presence of its farnesyl moiety and is excluded from regions of tight curvature, while lamin A/C is not. This multielement composite can deform on different length scales, which is crucial for maintaining nuclear integrity across various levels of mechanical strains. These fundamental organizing principles predict the behavior of the nuclear lamina and help clarify the disparate functional and structural consequences of the perturbation of individual lamina components.

Results

Differential Localization, Membrane Association, and Network Organization of Lamin B1 Versus A/C.

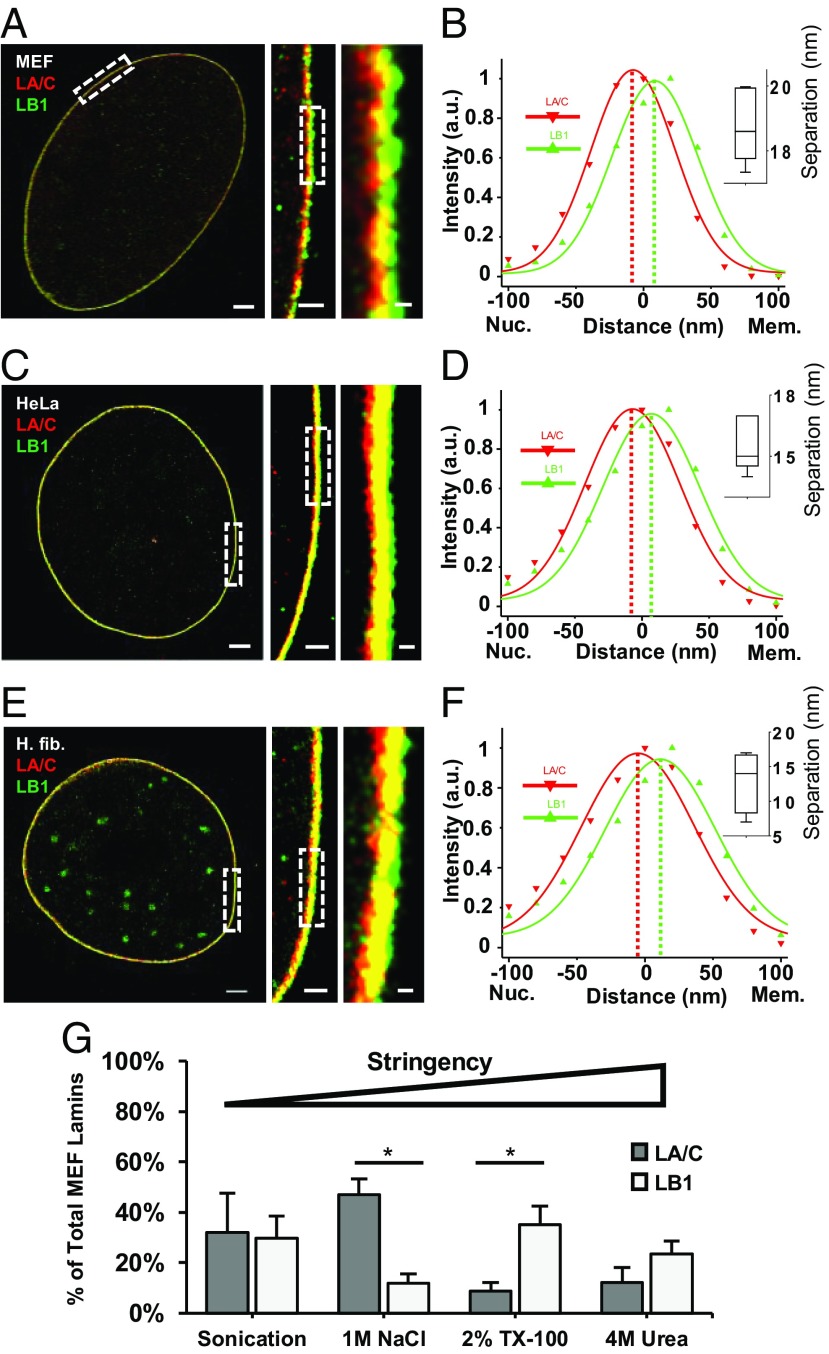

To visualize the spatial relationship between lamin A/C and B1, we used two-color STORM imaging in cells immunostained with primary antibodies against two nuclear lamina proteins: lamin A/C and lamin B1, and then with secondary antibodies conjugated with activator–reporter dye pair (17) [Cy2–Alexa Fluor (AF) 647 and AF405-AF647]. The use of the same reporter dye (Alexa Fluor 647) eliminates chromatic aberration, which is crucial for the precise localization of the two types of lamins. We specifically focused on the equatorial plane of the cell as the superior resolution in the x-y axes would allow us to better appreciate differences in spatial localization between the lamin A/C and B1 species across nuclear periphery. We discovered that lamin B1 preferentially localizes closer to the INM, whereas lamin A/C is localized closer toward the nucleoplasm; there is also significant spatial overlap between the A-type and B-type lamina meshworks. This pattern was consistent across different cell types and species including primary MEFs (Fig. 1 A and B and SI Appendix, Fig. S1A), HeLa cells (Fig. 1 C and D and SI Appendix, Fig. S1B), and primary human fibroblasts (Fig. 1 E and F and SI Appendix, Fig. S1C). Lamin B1 was localized closer to the INM compared with lamin A/C along the entirety of the nuclear periphery (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). To control against chromatic aberration artifacts associated with STORM imaging, these results were confirmed by switching the fluorescent dyes attached to immunolabeled lamin B1 and lamin A/C (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 A and B).

Fig. 1.

Spatially distinct localization and differential membrane binding of lamin B1 and lamin A/C. (A, C, and E) STORM images of immunofluorescently labeled lamin B1 (green) and lamin A/C (red) nuclear proteins in MEF (A), HeLa (C), and human fibroblast (E) nuclei at their equatorial planes. (Scale bar: 2 μm.) Rectangles denote Inset zoomed areas. (Inset scale bars: 500 and 100 nm.) (B, D, and F) Fluorescence-intensity profile plots across the nuclear envelopes in STORM images. x axis, distance (nm). Zero distance denotes center of nuclear lamina y axis: intensity (arbitrary units). (Inset) Box-and-whisker plot of separation (nm) between lamin A/C and B1 fluorescent-intensity peaks (n = 5 nuclei). (G) Quantification of fractional amount of nuclear lamin proteins solubilized in increasingly stringent sequential extractions in WT MEFs. Graph represents fraction of total lamin B1 and lamin A/C signal in each extraction from three independent experiments. Bars, means ± SEM. *P ≤ 0.05 (unpaired two-tailed t test).

To independently test association of lamin B1 with the INM, we subjected isolated MEF nuclei to extraction buffers of increasing stringency that sequentially isolate proteins from the lipid-bound fractions. We observed that lamin B1 requires more stringent conditions for its release into solution. In the two least stringent conditions, 80% of the total lamin A/C is extracted, compared to only 40% of lamin B1 in MEFs (Fig. 1G and SI Appendix, Fig. S3C). Since A-type and B-type lamin proteins have similar percentages of hydrophobic amino acids (lamin A: 32%; lamin C: 33%; lamin B1: 34%), differences in extraction profiles are most likely due to differences in membrane association. We replicated these results in HeLa cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 C and D), and they are consistent with our STORM imaging data that lamin B1 is more closely associated with the INM compared with lamin A/C. Localization of lamin B1 closest to the INM was also confirmed at the bottom surface of the cell nucleus using 3D STORM imaging in the x-z and y-z planes (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). For further confirmation, we carried out electron microscopy with immunogold labeling of lamin A/C and B1 proteins. These experiments clearly demonstrated a more peripheral localization for lamin B1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S5).

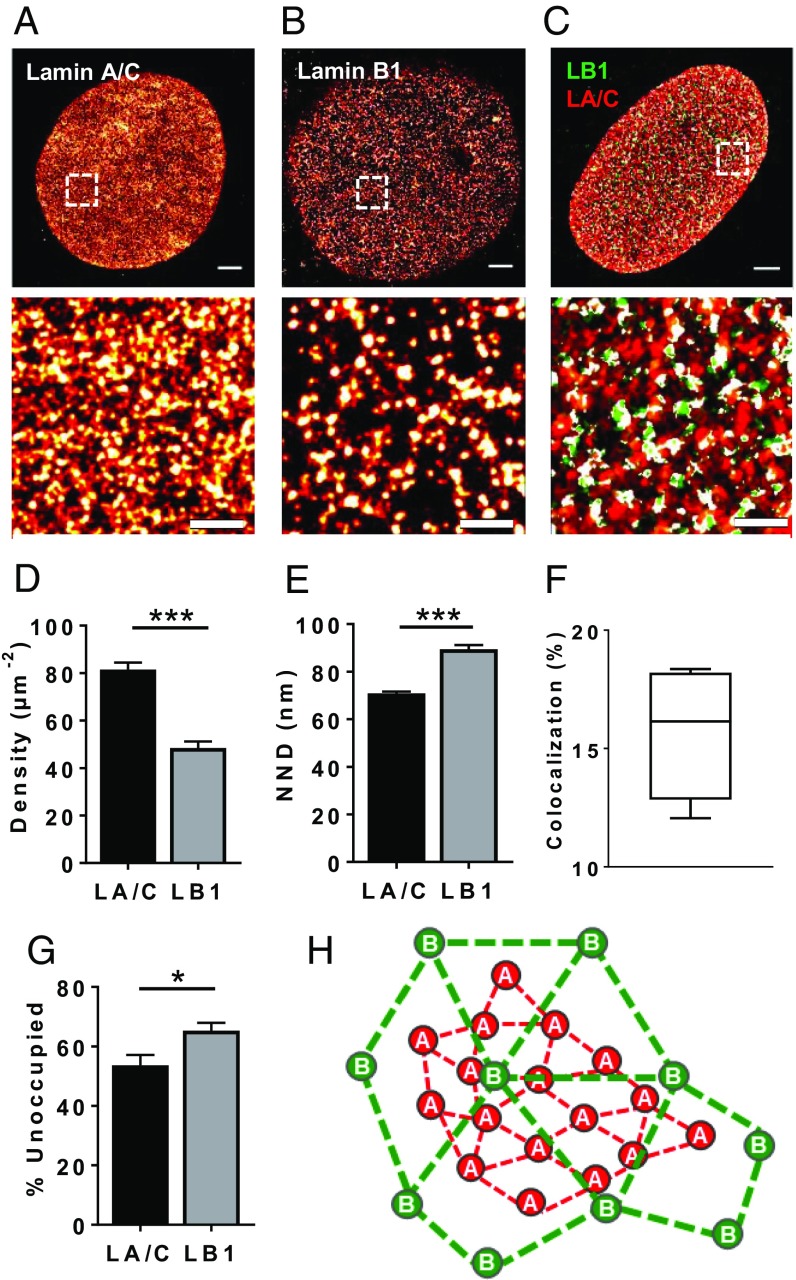

STORM images of WT MEF nuclei surfaces (Fig. 2 A and B) revealed that lamin A/C and lamin B1 networks exhibit different densities, with lamin A/C forming denser meshworks, while lamin B1 forms networks with clusters that are farther apart (Fig. 2 D and E), as indicated by nearest-neighbor distance (NND) measurements. Dual-color imaging (Fig. 2C) revealed mostly independent networks, with only 18% colocalization between the A-type and B1-type lamins (Fig. 2F). The meshwork formed by lamin B1 has larger interstitial spaces, as indicated by the higher percentage of unoccupied area (Fig. 2G). Taken together, these results suggest lamin B1 forms a less closely packed network with larger interstitial spaces, overlaying a denser lamin A/C network (Fig. 2H).

Fig. 2.

Lamin B1 and A/C have meshworks with distinct structural characteristics. (A–C) STORM images at the bottom nuclear surfaces of WT MEFs immunolabeled separately against lamin A/C (A), lamin B1 (B), or dual-color immunolabeled against lamin A/C (red) and lamin B1 (green) (C). White areas represent colocalization. Rectangles denote zoomed area. [Scale bars: Top, 2 μm; Bottom, 500 nm.] (D and E) Density (D) and NND (E) measurements of lamin B1 versus lamin A/C clusters in STORM-imaged WT MEF nuclei (n = 15 nuclei). (F) Box-and-whisker plot of degree of colocalization among lamin molecules calculated from dual-color STORM images (n = 5 nuclei). (G) Quantification of unoccupied area in lamin A/C versus lamin B1 meshworks (n = 15 nuclei). Bars, means ± SEM. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001 (unpaired two-tailed t test). (H) Simplified schematic representation of A-type and B-type lamins illustrating potential network characteristics based on NND calculations.

The C-Terminal Farnesyl Group Is Necessary for Proper Lamin B1 Localization and Network Organization.

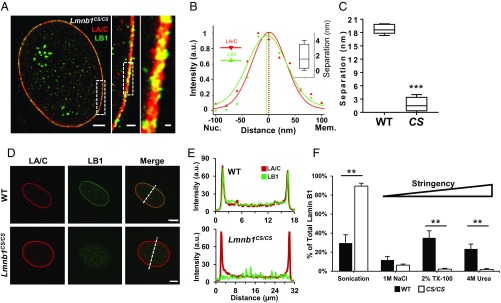

Given that lamin B1 retains its farnesyl group, we sought to test whether this moiety might be responsible for its association with the INM and examined MEFs derived from mice homozygous for a cysteine-to-serine mutation (Lmnb1CS/CS) in the CAAX domain, which inhibits farnesylation of lamin B1 (18). STORM images of Lmnb1CS/CS MEFs showed that lamin B1 was no longer localized closer to the INM (Fig. 3A), and the relative intensity profiles revealed a lamin B1 signal completely overlapping with that of lamin A/C (Fig. 3 B and C).

Fig. 3.

The C-terminal farnesyl group determines the spatial organization of lamin B1. (A) STORM image at equatorial plane of an immunofluorescently labeled Lmnb1CS/CS MEF nucleus. (Scale bar: 2 μm.) Rectangles denote Inset zoomed areas. (Inset scale bars: 500 and 100 nm.) Lamin B1, green; lamin A/C, red. (B) Fluorescence intensity profile plots across the STORM imaged Lmnb1CS/CS MEF nuclear envelope. x axis, distance (nm); y axis, intensity (arbitrary units). (Inset) Box-and-whisker plot of separation (nm) between lamin A/C and B1 fluorescent-intensity peaks from five nuclei. (C) Comparison of lamin B1 and lamin A/C intensity peak separation in WT versus Lmnb1CS/CS MEFs (n = 5 nuclei). (D) Confocal immunofluorescence images of representative WT and Lmnb1CS/CS MEF nuclei taken at the equatorial plane. Lamin B1, green; lamin A/C, red. (Scale bar: 10 μm.) Dotted lines depict measurement lengths of fluorescent-intensity plots shown in Fig. 5E. (E) Fluorescence intensity profile plots across representative WT and Lmnb1CS/CS nuclei. The sharp peaks at each end of the lamin A/C and WT lamin B1 plots represent bright peripheral staining. x axis, measurement distance (μm); y axis, fluorescence intensity (arbitrary units). (F) Comparison of sequential lamin B1 extractions in WT versus Lmnb1CS/CS cells. The graph represents fraction of total lamin B1 signal in each extraction from three independent experiments. Bars, means ± SEM. **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001 (unpaired two-tailed t test).

Confocal microscopy of Lmnb1CS/CS nuclei at their equatorial planes demonstrated an abnormal distribution of lamin B1 throughout the nucleus (Fig. 3D), including abnormally high lamin B1 levels in the nucleoplasm, whereas lamin A/C appears to be unaffected (Fig. 3E). Quantifying the ratio of fluorescence intensity at the nuclear periphery (P) to the intensity at the nuclear center (C) (SI Appendix, Fig. S6A), the P/C ratio of lamin B1 is significantly smaller in Lmnb1CS/CS MEFs compared with WT MEFs (SI Appendix, Fig. S6B), whereas lamin A/C ratios remains unchanged. Although lamin B1 protein levels are slightly reduced in Lmnb1CS/CS compared with WT MEFs (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 C and D), a reduction of lamin B1 protein does not result in altered localization. RNAi-induced lamin B1 reduction in HeLa cells still demonstrated outward localization of lamin B1 closest to the INM (SI Appendix, Figs. S6 E and F, and S7C). We measured extraction of lamin proteins from nuclei isolated from Lmnb1CS/CS MEFs (SI Appendix, Fig. S6G), finding that a striking 89.4 ± 3.1% of the total lamin B1 was extracted in the least stringent fraction (Fig. 3F), compared with 29.6 ± 8.7% in WT cells, and is consistent with previous results using farnesyl transferase inhibitors (19). Lamin A/C extraction profiles remained unchanged across WT and Lmnb1CS/CS cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S6H). These data confirmed the STORM imaging results, indicating that the farnesyl group of lamin B1 is required for its proper localization to the INM.

The STORM images at the nuclear surface in the Lmnb1CS/CS MEFs revealed a dramatic alteration in the lamin B1 network, which showed a significant reduction in spatial density with a corresponding increase in NND measurements. However, we did not observe any alteration in lamin A/C distribution (SI Appendix, Fig. S8).

Lamin B1 Localization at the Nuclear Envelope Is Curvature-Dependent.

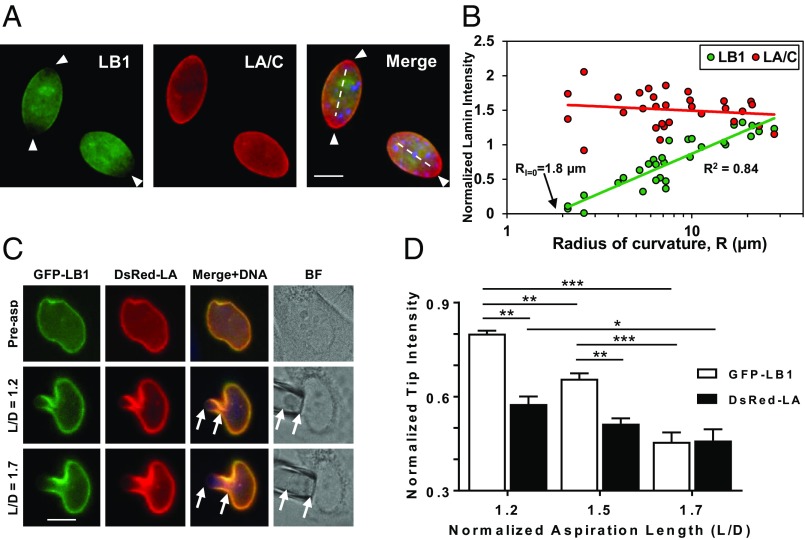

Wide-field fluorescence images of WT MEF nuclei revealed a differential localization of lamin B1 and lamin A/C at the nuclear rim (Fig. 4A): in more ellipsoidal nuclei, lamin B1 intensity was reduced at the poles. We quantified local radius of curvature, R, as a function of normalized lamin intensity (SI Appendix, Fig. S9A for methodology) across WT MEF nuclei. The intensity profiles of lamin staining with respect to R showed no correlation with lamin A/C, but an exceptionally strong correlation with lamin B1 (Fig. 4B). Regions of lower R had reduced lamin B1 intensity and an extrapolation of the fit line to zero lamin B1 intensity suggests that curved structures with a radius of less than 1.8 μm would be devoid of lamin B1.

Fig. 4.

Lamin B1 meshwork is curvature and strain-responsive. (A) Wide-field fluorescent microscopy images of WT MEF nuclei displaying differential localization of lamin B1 and lamin A/C across the nucleus. Dashed lines represent major axes. The vertices at the ends of the major axis are defined as the nuclear poles. Arrowheads point to areas of decreased lamin B1 intensity. (Scale bar: 10 µm.) (B) Plot of normalized lamin intensity versus radius of curvature R for 30 points across 17 nuclei, with logarithmic trend lines. At the x intercept, R = 1.8 µm. (C) MEFs were doubly transfected with GFP-LMNB1 and DsRed-LMNA plasmids and then aspirated with a micropipette. Normalized aspiration length, L/D, is defined as the aspirated projection length, L, divided by the diameter of the micropipette, D. Arrows point to aspiration tip and base. (Scale bar: 10 µm.) (D) Graph of lamin intensities at the aspiration tip versus L/D (n = 5). Lamin intensities at the aspiration tip were normalized to its intensity throughout the rest of the nucleus. Bars, means ± SEM. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001 (two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test).

Alternatively, plotting of lamin intensity versus bending energy of the nuclear envelope can be approximated by the equation for a 2D network: (20, 21). Since the bending modulus κ is a constant material property, we plot the effective bending energy as a function of 1/R2 (SI Appendix, Fig. S9B). Lamin A/C localization is independent of lamina bending energy. In contrast, lamin B1 intensity is an extremely strong function of bending energy. An elongated nucleus forms a tight curve (i.e., high bending energy) at polar ends; as a result, these regions are more likely to be devoid of lamin B1. Consistent with our epifluorescence data, STORM images of elongated MEF nuclei also show the characteristic loss of lamin B1 at the polar ends (SI Appendix, Fig. S9C).

To confirm the strain-dependent localization of the A- and B-type lamins, we used micropipette aspiration to induce and increase strain and visualize lamin intensity at the tip in the pipette, which is the region of highest strain (22) (Fig. 4C). At small aspiration lengths, normalized GFP–lamin B1 intensity is higher than normalized DsRed–lamin A intensity at the tip, which suggests that the stiff lamin A is resistant to deformation, as expected, compared with lamin B1. With increasing aspiration length, the normalized GFP–lamin B1 intensity significantly decreases at the tip, while normalized DsRed–lamin A intensity remains relatively unchanged (Fig. 4D). These findings are consistent with our imaging results and indicate that the network deformation of lamin B1 is influenced by strain at the pipette tip.

Bleb Architecture Is Dependent upon Lamin Levels and Localization.

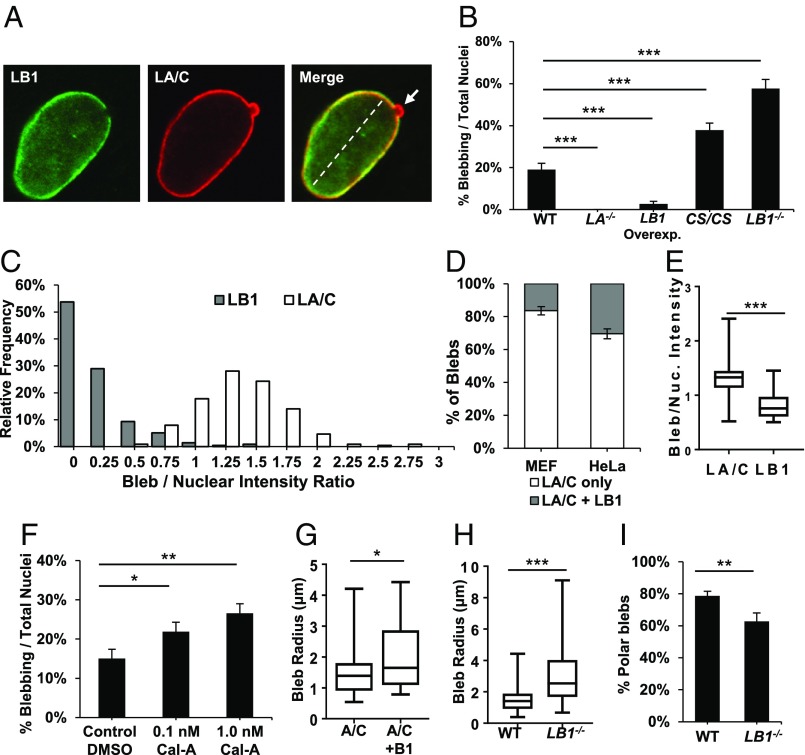

One physiological consequence of curvature-dependent localization of the A- and B-type lamins is evident in the structure of nuclear blebs, which are characteristic outward protrusions of the nuclear lamina. Blebs were initially reported as a consequence of nuclear lamin perturbations, most pronounced in lamin B1-null and HGPS cells (8, 13, 23). However, we observed that these blebs were also present in a small fraction of WT MEFs (19.1 ± 2.9%; Fig. 5 A and B) and untreated HeLa cells (12.2 ± 1.7%; SI Appendix, Fig. S10C). Plotting the ratio of bleb lamin fluorescence intensity to nuclear fluorescence intensity reveals that 80% of blebs were devoid of lamin B1 (Fig. 5C). All nuclear blebs contained lamin A/C, while only a subset also contained lamin B1 (16.4 ± 2.5% in MEFs, 30.4 ± 3.0% in HeLa cells; Fig. 5D). No blebs contained lamin B1 without lamin A/C also present. In the blebs that did contain lamin B1, the normalized fluorescence intensity of lamin B1 within the bleb was significantly lower than that of lamin A/C (Fig. 5E), also suggesting that lamin B1 is depleted from blebs.

Fig. 5.

Lamin structure determines its roles in maintaining nuclear shape. (A) Confocal images of a WT MEF nucleus at the equatorial plane showing a typical nuclear envelope protrusion referred to as a bleb (arrow). The dashed line represents major axis. (B) Quantification of bleb frequencies among WT (n = 178), Lmna−/− (n = 178), Lamin B1-overexpressing (n = 182), Lmnb1CS/CS (n = 201), and Lmnb1−/− (n = 201) MEF nuclei. (C) Histogram of bleb lamin intensity relative to nuclear body intensity in WT MEFs (n = 214). Median ratios: 1.34 (LA/C), 0.10 (LB1). (D) Frequencies of blebs that contain LA/C only versus both LA/C plus LB1 in primary MEFs (n = 225) and HeLa cells (n = 230). (E) Box-and-whisker plot of lamin fluorescence intensity ratios among blebs that contain both lamin A/C and lamin B1 in WT MEFs (n = 24). (F) Nuclear bleb frequencies in HeLa cells treated with 0.1 nM (n = 288) and 1 nM Cal-A (n = 324), compared with DMSO-treated control (n = 220). (G) Radius measurements of blebs containing only lamin A/C (n = 158) versus both A/C and B1 (n = 31). (H) Radius measurements of blebs in WT (n = 189) versus Lmnb1−/− (n = 87) MEFs. (I) Percentages of polar-localized blebs in WT (n = 206) versus Lmnb1−/− (n = 87) MEFs. Bars, means ± SE. *P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001 (χ2 tests were used for B, F, and I; Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test for E, and unpaired two-tailed t test with Welch’s correction for G and H).

To determine whether altering levels of the different lamin subtypes had any effect on bleb frequency, we then examined bleb formation in WT, Lmnb1−/−, and Lmna−/− MEFs (SI Appendix, Fig. S10 A and B). Interestingly, we observed that while Lmna−/− MEFs were highly elongated and displayed ragged gaps at the polar ends, no blebs were present. In contrast, we observed a marked increase of bleb frequency in Lmnb1−/− MEFs. Lmnb1CS/CS MEFs also had more frequent blebbing nuclei, but not to the degree seen in Lmnb1−/− cells (Fig. 5B). In agreement with the lamin-null MEF data, siRNA-induced reduction of lamin B1 increased bleb frequency, while the reduction of lamin A decreased bleb frequency (SI Appendix, Fig. S10C). Therefore, a possible role of the outer lamin B1 meshwork may be to prevent the A-type lamins underneath from expanding outward and forming nuclear envelope protrusions.

We hypothesized that rather than solely arising as a consequence of nuclear lamin perturbations, bleb formation may be a mechanism to redistribute tension on the lamina due to cytoskeletal forces exerted on the nucleus. To test this, HeLa cells were treated with 0.1 and 1 nM calyculin A (Cal-A), a potent PP1 and PP2A-C phosphatase inhibitor that induces contraction of the actin-myosin cytoskeleton (24). We reasoned that intensifying intracellular stress to promote rapid nuclear compression would lead to an increase of bleb frequencies. Cal-A treatment indeed resulted in increased bleb frequencies over control cells in a dose-responsive manner (Fig. 5F). The short treatment period (30 min) ensures that the differences in bleb frequencies are not due to nuclear reorganization induced by cell division. To confirm that the increased blebbing frequency was due to increased actin–myosin contractility and not due to off-target phosphorylation caused by Cal-A treatment, we used the cell-permeable myosin II inhibitor blebbistatin to reduce intracellular pressure by suppressing cell contraction. Blebbistatin treatment resulted in a dose-dependent decrease of blebbing nuclei (SI Appendix, Fig. S10D). Notably, it eliminated Cal-A’s ability to induce bleb formation, indicating that blebs likely arose due to increased intracellular pressure and not from nonspecific effects of calyculin treatment.

The architecture of the blebs allows us to test predictions that arise out of our model of the nuclear lamina, where the lamin B1 network is located toward the outside of lamin A/C, and the location of lamin B1 is curvature-dependent. Based on our findings, we expect that lamin B1 is likely to be excluded from tightly curved regions of the nuclear envelope. Consistent with this prediction, we found that blebs containing lamin B1 are larger on average than lamin A/C-only blebs (Fig. 5G). In addition, blebs that form in Lmnb1−/− MEFs are significantly larger than those in WT cells (Fig. 5H). Further proof of the functional consequences of our model is seen in the location of blebs. If a role for lamin B1 is to stabilize the outward protrusion of the lamin A/C network, we would expect to see a higher frequency of blebs in regions depleted of lamin B1. In agreement with our model, we observe most blebs form at the major axis poles, where the radius of curvature is low, resulting in a consequent depletion of lamin B1. However, in Lmnb1−/− MEFs, where the constraining effects of lamin B1 are no longer present, blebs assume a more random distribution with a significant reduction in polar blebs (Fig. 5I).

To further test our hypothesis that lamin B1 inhibits the lamin A/C meshwork from protruding outward, we examined lamin B1-overexpressing MEFS (SI Appendix, Fig. S10E). Compared with WT and untreated cells, lamin B1-overexpressing cells had a significantly lower frequency of blebbing nuclei (Fig. 5B and SI Appendix, Fig. S10F). By increasing lamin B1 expression, we could almost eliminate the formation of nuclear blebs.

Discussion

Superresolution localization microscopy is a powerful imaging tool for simultaneous visualization of multiple molecular species at nanometer resolutions (17). Here, we have used STORM combined with quantitative image analysis to identify the spatial organization of A- and B-type lamins. We find that the lamin B1 meshwork is closest to the INM and forms a less dense outer rim around the more tightly spaced lamin A/C meshwork facing the nucleoplasm, with a spatial separation of ∼15–20 nm. Such precise localization of the two lamin species was achieved by several key technical attributes of our approach. First, it required chromatic aberration-free, two-color superresolution imaging. A complete correction of chromatic aberration is often difficult to achieve, especially when the imaging target is farther away from the coverslip surface (as in our case of imaging equatorial plane of the nuclear periphery). To overcome this hurdle, we used the same reporter dye in the activator–reporter dye pairs in two-color STORM imaging to essentially eliminate any chromatic aberration. Second, by averaging spatial distribution around the nuclear periphery, we can quantify the separation of different lamin types at a higher precision than the STORM imaging resolution of ∼20 nm (25). Third, focusing on the equatorial plane also maximizes the spatial resolution by imaging the projection of the cross-sectional profiles of the two lamin types across the nuclear periphery.

Our biochemical data confirm the STORM imaging observations that lamin B1 is more closely associated with INM than lamin A/C and that this association is dependent upon the farnesylation of lamin B1. All lamins are initially farnesylated, but only B-type lamins retain their farnesyl group after prelamin A undergoes proteolytic cleavage at its C terminus (2). This farnesyl tail can allow lamin B1 to tightly associate with the INM, similar to the way Ras GTPases anchor to the cell membrane (26, 27), and provides a rationale for the retention of the farnesyl group by lamin B1. Interestingly, although the lamin B1 farnesyl mutant significantly altered the lamin B1 network structure, consistent with earlier reports using conventional fluorescence microscopy (18), our results also show that it did not alter lamin A/C distribution, suggesting that proper localization of lamin B1 is not required for the integrity of the lamin A/C network.

While farnesylation of lamin B1’s CAAX domain is important for its peripheral localization, other posttranslational modifications might also be maintaining nuclear envelope stability. Inhibition of Rce1-mediated endoproteolysis or Icmt-mediated carboxymethylation of lamin B1’s CAAX domain has been shown to result in compromised structural integrity of the lamina, namely with gaps in the lamin B1 meshwork through which chromatin herniations can be seen (19). Farnesylation of lamin B1 may be critical for its proper localization adjacent to the INM, but it might not be the only factor. This can now be tested using the STORM imaging protocol we have described.

Taken together with their relative spatial organization at the nuclear periphery (the less dense lamin B1 network overlaying a more closely spaced A-type lamin network), lamin B1 is also less likely to be present in tightly curved structures and is more responsive to bending energy. This implies that the nuclear lamina is composed of independent mechanical elements with distinct properties. Lamin A/C has been previously shown to contribute to the mechanical stiffness of the nucleus (8). We show here that it forms a tighter meshwork that functionally maintains the mechanical integrity of the nuclear lamina regardless of nuclear shape. In contrast, the lamin B1 meshwork has larger interfilament spaces that are more bending energy-responsive, stabilizing the nuclear membrane structure by complementing the rigidity of lamin A/C. This complement of stiff and strain-dependent deformable filament structures is not unique to the nuclear envelope. Similar multielement mechanical complements are also found throughout the cytoskeleton (28).

Although we are lacking data on lamin B2’s meshwork in this study, most of the nuclear envelope shape changes can be sufficiently modeled with the physical arrangement of lamin B1’s meshwork relative to that of A-type lamins, as well as their mechanical properties. Although knockdown of lamin B2 results in abnormal nucleolar morphology (29), Lmnb2−/− mouse fibroblasts do not have significant irregularities in their lamin meshwork (15) and do not exhibit higher frequencies of nuclear blebs than WT fibroblasts (30). It is therefore possible that lamin B2 might contribute very little to nuclear shape dynamics, although this has yet to be confirmed.

Previous studies have shown that individual lamin A and lamin C proteins preferentially homodimerize to form independent but similar mesh-like structures, with little detectable interaction with lamin B1 (31–33). Although we have not differentiated between the A- and C-type lamins in our experiments, our model of the nuclear lamina is not incompatible with this finding, since it is not predicated upon A-type lamins together forming a single, heteromultimeric meshwork at the nuclear periphery. The higher cluster density of lamin A/C’s meshwork that we have observed in our STORM data may in fact be a combination of the lamin A network overlapping a separate lamin C network. Although we show A-type lamins form meshworks that preferentially localize closer to the nucleoplasm, a future direction would be to determine if there are spatial localization differences between lamin A and lamin C networks, as we have observed between lamin A/C and lamin B1, using our sensitive dye pair STORM imaging protocol.

Blebs are often considered to be related to pathological phenomena, especially in the context of laminopathies like HGPS (34) and Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy (35), metastasizing cancers (36, 37), or as consequences of nuclear lamina perturbations such as lamin B1 silencing (13). However, we suggest that nuclear blebs are not necessarily pathological abnormalities but may be useful for the rapid nuclear morphology changes needed to respond to intracellular forces such as cytoskeleton contraction. This is supported by our results where a stimulated increase of intracellular forces using Cal-A resulted in significantly increased numbers of blebs. Our data are consistent with a recent report that blebs are also found in WT cells, and these are usually lacking lamin B1 (38). All blebs contain lamin A/C but only a minority also contain lamin B1. In these blebs, lamin B1 is significantly depleted. Together, these results suggest lamin A/C is a major driver of bleb formation. These findings are consistent with another report, published while our manuscript was under review, finding that depletion of all lamins leads to a complete absence of blebs (39).

Our micropipette aspiration experiments showed that localization of GFP–lamin B1 and DsRed–lamin A/C along various aspiration lengths is dissimilar to what is observed in naturally occurring blebs. It is important to note that micropipette aspiration induces hyperphysiological strains—high force applied over short times—that allow us to induce energy-dependent deformation independently of cellular forces and visualize lamin network deformation at a rate faster than protein exchange or other biological processes. As such, these shorter time scales and higher forces probably contribute to the distribution of lamin A/C and lamin B1 appearing different from in blebs that occur under normal cellular forces of adherent cells.

We propose that most blebs lack lamin B1 for two main reasons: first, blebs form more readily in the absence of the outer stabilizing layer of lamin B1; and, second, because of the curvature dependent localization, lamin B1 is less likely to be located within smaller structures like blebs once they are formed. Whether lamin B1-containing blebs develop from different cellular processes as the blebs containing only A-type lamins remains to be determined. Lamin B1 degradation has been shown to be mediated by autophagy through nucleus-to-cytoplasmic transport of vesicles that deliver lamin B1 to the lysosome (40). It is possible that the lamin B1-containing blebs represent nascent stages of such autophagic vesicles.

We observed a marked difference in bleb orientation among WT and Lmnb1−/− MEF nuclei. Nearly 80% of blebs were positioned adjacent to the major axis poles in WT nuclei. With the complete lack of lamin B1, we observed a more random assortment of bleb positioning. In WT cells, the poles are the regions of high curvature and are consequently mostly devoid of lamin B1, while Lmnb1−/− cells are uniformly devoid of lamin B1. The blebbing pattern in these two cell types thus mirrors the depleted laminB1 localization and is consistent with our hypothesis that lamin B1 plays a role in suppressing bleb formation in the nuclear envelope. While high curvature strain as a mechanism for preferentially polar bleb formation, as previously proposed, still holds (38), our results suggest that this mechanism is also mediated by the absence of lamin B1 at these locations.

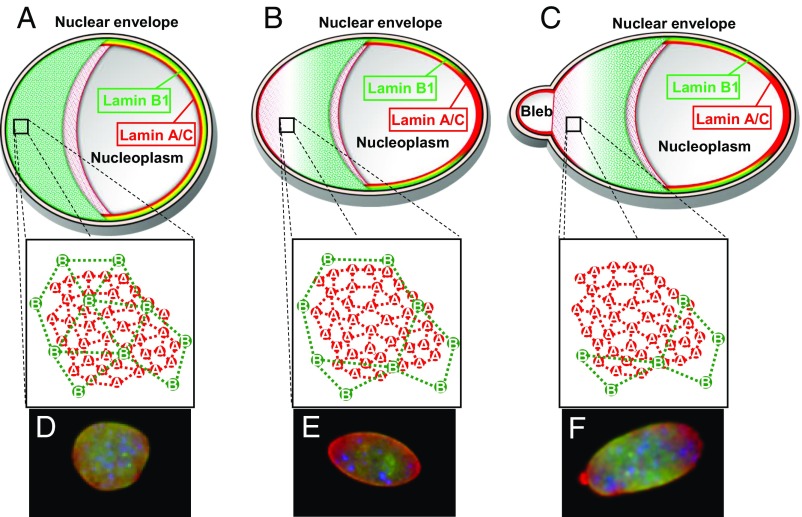

In summary, we have identified a model for the spatial organization of the nuclear lamina based on two critical principles: (i) lamin B1 forms a looser, outer meshwork facing the nuclear membrane, while lamin A/C forms a tighter, inner meshwork facing the nucleoplasm; and (ii) lamin B1’s meshwork is more curvature- and strain-responsive than lamin A/C’s meshwork, which affects its localization in tightly curved structures (Fig. 6). This model reveals a role for lamin B1 in preventing the A-type lamin meshwork from protruding outward and can predict the disparate structural consequences of perturbing individual lamina components.

Fig. 6.

Schematic representation of lamin organization at the nuclear envelope. Lamin B1’s meshwork (green) lies closest to the INM, while lamin A/C’s meshwork (red) faces the nucleoplasm. (A) In circular or slightly elliptical nuclei, the B-type lamin meshwork is sufficient to contain the underlying A-type lamin meshwork. (B) Regions of high curvature in elongated nuclei can result in a dilation or loss of the lamin B1 meshwork. (C) Lamin A/C forms blebs through the gaps within the lamin B1 meshwork. (D–F) Representative MEF nuclei displaying circular (D), elongated (E), and blebbed (F) morphologies as illustrated in the above models. Lamin B1, green; lamin A/C, red, DNA, blue.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture.

Primary MEFs {WT, TRE-FLAG-LMNB1;ROSA26-rtTA, Lmnb1CS/CS [Jung et al. (18)], Lmnb1−/− [Vergnes et al. (41)], and Lmna−/− [Lammerding et al. (8)]}, human fibroblasts, and HeLa cells were cultured in complete DMEM [high-glucose DMEM (Corning) supplemented with 10% FBS (Fisher), 2 mM l-glutamine (Millipore), and 1% penicillin streptomycin (HyClone)]. Cells were incubated in a humidified chamber at 37 °C and 5% CO2. When cells reached 90–100% confluence, they were trypsinized, diluted, and replated using fresh media. Lamin B1 overexpression was induced in TRE-FLAG-LMNB1;ROSA26-rtTA transgenic MEFs by adding 2 μg/mL doxycycline in growth medium for 5 d. For Cal-A and blebbistatin treatments, HeLa cells grown on coverslips were treated with 0.1 and 1 nM Cal-A (no. 508226; Sigma) for 30 min, or 10, 50, and 100 μM blebbistatin (no. 203389; Sigma) for 2 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Cells were washed and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution in PBS immediately after treatment.

STORM Imaging and Analysis.

Cells for STORM imaging were prepared as previously described (42). Rabbit anti-lamin B1 (no. ab16048; Abcam) were diluted 1:600 and/or mouse anti-lamin A/C (no. 4777; Cell Signaling) were diluted 1:300 in PBS plus 3% BSA and incubated on the cells overnight at 4 °C. The next morning, cells were washed with PBS three times for 5 min each at room temperature. Secondary antibodies were diluted in PBS plus 3% BSA and incubated with the cells for 2 h at room temperature in the dark. Unconjugated secondary antibodies (nos. 711-005-152 and 715-005-150; Jackson ImmunoResearch) were conjugated with AF647 (no. A20006; Thermo Fisher Scientific) in the laboratory of Y.L. AF647-conjugated secondary antibodies were used for single-color STORM imaging. For two-color STORM imaging based on dye pairs, secondary antibodies labeled with activator–reporter dye pairs (AF405-AF647, Cy2-AF647) were used. AF405-AF647 conjugated donkey anti-mouse secondary antibody was used to label lamin A/C, and Cy2-AF647 conjugated donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibody was used to label lamin B1. For the dye-switch experiment, AF405-AF647 conjugated donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibody was used to label lamin B1, and Cy2-AF647 conjugated donkey anti-mouse secondary antibody was used to label lamin A/C. Immediately before imaging, the buffer was switched to STORM imaging buffer [10% wt/vol glucose (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.56 mg/mL glucose oxidase (Sigma-Aldrich), and 0.17 mg/mL catalase (Sigma-Aldrich)]. For single-color imaging, 0.14 M β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich) was used, and for two-color imaging, 0.1 M mercaptoethylamine (Sigma-Aldrich) was used. Single-color STORM imaging was performed on a custom-built system using an Olympus IX71 inverted microscope frame with a 60× oil objective. Fluorescent beads [0.1 μm diameter (no. F8803; Fisher Scientific), excited using 488 nm laser] were used as fiduciary markers on the coverslip to correct for 3D system drift every 200 frames. Two-color STORM images using dye pairs were acquired on a commercial imaging system (N-STORM; Nikon Instruments). The samples were periodically activated with a sequence of 405-nm, 488-nm laser pulses and then imaged with the 647-nm laser. In each switching cycle, the activation laser was turned on for one frame, followed by three frames of illumination with the red imaging laser. A total of 40,000 frames, including 10,000 activation frames and 30,000 imaging frames for each channel, were acquired at an exposure time of 20 ms. Imaging frames immediately following an activation pulse were recognized as controlled activation events, and a color was assigned accordingly. A crosstalk subtraction algorithm was used to subtract the nonspecific activation signal (17). Nuclei were imaged at the equator for measuring lamina thickness and relative localization. The bottom surfaces of nuclei were imaged to minimize curvature artifacts. The reconstruction of a superresolution image and Gaussian clustering were performed using a custom program written in Matlab 2015 (MathWorks), as previously described (43). The degree of colocalization was calculated using Clus-DoC algorithm (44) and defined as the degree of colocalization in lamin A/C and lamin B1 with respect to the combined lamin A/C and lamin B1. For measuring lamina thickness, the nuclear periphery of the superresolution image was automatically divided into numerous small segments at a length of ∼50 nm. Intensity peaks were measured along the steepest gradient perpendicular to the nuclear envelope and averaged. The intensity profile was plotted as distance (x axis) versus normalized lamin intensity (y axis), and thicknesses was defined as the full width at half-maximum.

Isolation of Nuclei.

Low-passage cells were seeded in 100-mm tissue culture dishes (Thermo BioLite) and grown to 90% confluence. Nuclei were isolated as previously described (45), with modifications. The cells were washed once with 3 mL of ice-cold PBS and then scraped down with 1 mL of cold PBS into 1.5-mL microcentrifuge tubes. Samples were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 15 s at 4 °C, and the supernatants were discarded. Cell pellets were resuspended in 1 mL of cold PBS+IGEPAL [1× PBS plus 0.1% IGEPAL CA-630 (Sigma) plus protease inhibitors], triturated 5× on ice with a 1,000 μL pipet tip, and 100 μL was transferred into new microcentrifuge tubes as the whole cell fraction. Remaining volumes were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 15 s at 4 °C. Supernatants were transferred to new microcentrifuge tubes labeled “cytosol.” Pellets were resuspended in 1 mL of PBS+IGEPAL and then centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 15 s at 4 °C, and the supernatants were discarded. Remaining pellets were used for sequential protein extractions. Cytosol samples were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 1 min at 4 °C, and then 300 μL of the supernatant was transferred to new microcentrifuge tubes as the clean cytosolic fraction.

Sequential Extraction of Nuclear Envelope Proteins.

Subfractionation of nuclear proteins was performed as previously described (46). Nuclear pellets were resuspended in 300 μL of nuclear isolation buffer [10 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), 2 mM MgCl2, 25 mM KCl, 250 mM sucrose, 1 mM DTT, protease inhibitors]; 50 μL of each sample were transferred to new microcentrifuge tubes as the “whole nuclei” fraction. Samples were sonicated on ice with two 5-s pulses at 10-μm amplitude and then centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were transferred to new microcentrifuge tubes as the “sonication” fraction. Pellets were resuspended in 250 μL of nuclear extraction buffer [20 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), 1 M NaCl, protease inhibitors] and incubated for 20 min at room temperature with end-over-end rotation. After incubation, samples were centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C, and the supernatants were transferred to new microcentrifuge tubes as the “1 M NaCl” fraction. Extractions were repeated on the pellets using 250 μL of nuclear extraction buffer with 2% vol/vol Triton X-100, 4 M urea, then 8 M urea in sequential incubations. All protein extracts were stored at −80 °C until ready for immunoblotting.

Statistical Analysis.

Two-sided t tests were used to calculate statistical significance between two groups. For micropipette aspiration comparisons, two-way ANOVAs were used followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. For sequential protein extractions, lamin signal percentages were arcsine-transformed before statistical analysis. χ2 tests were used to assess statistical significance of blebbing ratios. Bleb versus nuclear lamin intensity differences were compared using Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test. A P value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The following convention for representing P values was followed: *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001. All error bars represent SE unless otherwise specified. Data were graphed and analyzed in Microsoft Excel 2016 and GraphPad Prism 7. Additional materials and methods information and SI figures are located in SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the K.N.D., Y.L., and Q.S.P. labs for helpful discussions; Loren Fong for help with providing the Lmnb1−/−, Lmna−/−, and Lmnb1CS/CS MEFs; the Center for Biological Imaging at the University of Pittsburgh for assistance with STORM, EM, and confocal imaging; and the Biomedical Mass Spectrometry Center for helpful discussions. This work was supported by NIH Grant R01NS095884 and National Multiple Sclerosis Society Research Grant 5045A1 (to Q.S.P.); NSF Civil, Mechanical and Manufacturing Innovation Grant 1634888 (to K.N.D.); NIH Grant EB003392 (to T.J.A. and K.N.D.); NIH Grants R01EB016657 and R01CA185363 (to Y.L.); and NIH Grants 1S10RR019003-01 and 1S10RR025488-01 (to D.B.S.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1810070116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Gerace L, Huber MD. Nuclear lamina at the crossroads of the cytoplasm and nucleus. J Struct Biol. 2012;177:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ho CY, Lammerding J. Lamins at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:2087–2093. doi: 10.1242/jcs.087288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burke B, Stewart CL. The nuclear lamins: Flexibility in function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:13–24. doi: 10.1038/nrm3488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biamonti G, et al. The gene for a novel human lamin maps at a highly transcribed locus of chromosome 19 which replicates at the onset of S-phase. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:3499–3506. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.8.3499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin F, Worman HJ. Structural organization of the human gene (LMNB1) encoding nuclear lamin B1. Genomics. 1995;27:230–236. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin F, Worman HJ. Structural organization of the human gene encoding nuclear lamin A and nuclear lamin C. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:16321–16326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dechat T, et al. Nuclear lamins: Major factors in the structural organization and function of the nucleus and chromatin. Genes Dev. 2008;22:832–853. doi: 10.1101/gad.1652708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lammerding J, et al. Lamins A and C but not lamin B1 regulate nuclear mechanics. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:25768–25780. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513511200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sullivan T, et al. Loss of A-type lamin expression compromises nuclear envelope integrity leading to muscular dystrophy. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:913–920. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.5.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jung HJ, et al. Regulation of prelamin A but not lamin C by miR-9, a brain-specific microRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:E423–E431. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111780109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim Y, et al. Mouse B-type lamins are required for proper organogenesis but not by embryonic stem cells. Science. 2011;334:1706–1710. doi: 10.1126/science.1211222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coffinier C, et al. Deficiencies in lamin B1 and lamin B2 cause neurodevelopmental defects and distinct nuclear shape abnormalities in neurons. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:4683–4693. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-06-0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shimi T, et al. The A- and B-type nuclear lamin networks: Microdomains involved in chromatin organization and transcription. Genes Dev. 2008;22:3409–3421. doi: 10.1101/gad.1735208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Padiath QS, et al. Lamin B1 duplications cause autosomal dominant leukodystrophy. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1114–1123. doi: 10.1038/ng1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shimi T, et al. Structural organization of nuclear lamins A, C, B1, and B2 revealed by superresolution microscopy. Mol Biol Cell. 2015;26:4075–4086. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E15-07-0461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turgay Y, et al. The molecular architecture of lamins in somatic cells. Nature. 2017;543:261–264. doi: 10.1038/nature21382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bates M, Huang B, Dempsey GT, Zhuang X. Multicolor super-resolution imaging with photo-switchable fluorescent probes. Science. 2007;317:1749–1753. doi: 10.1126/science.1146598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jung HJ, et al. Farnesylation of lamin B1 is important for retention of nuclear chromatin during neuronal migration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:E1923–E1932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303916110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maske CP, et al. A carboxyl-terminal interaction of lamin B1 is dependent on the CAAX endoprotease Rce1 and carboxymethylation. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:1223–1232. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200303113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Israelachvili JN. Intermolecular and Surface Forces. 3rd Ed. Academic; Burlington, MA: 2011. pp. 382–385. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boal DH. Mechanics of the Cell. 2nd Ed. Cambridge Univ Press; Cambridge, UK: 2012. pp. 156–171. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Discher DE, Boal DH, Boey SK. Simulations of the erythrocyte cytoskeleton at large deformation. II. Micropipette aspiration. Biophys J. 1998;75:1584–1597. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)74076-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Candelario J, Sudhakar S, Navarro S, Reddy S, Comai L. Perturbation of wild-type lamin A metabolism results in a progeroid phenotype. Aging Cell. 2008;7:355–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00393.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishihara H, et al. Calyculin A and okadaic acid: Inhibitors of protein phosphatase activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;159:871–877. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)92189-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szymborska A, et al. Nuclear pore scaffold structure analyzed by super-resolution microscopy and particle averaging. Science. 2013;341:655–658. doi: 10.1126/science.1240672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seabra MC. Membrane association and targeting of prenylated Ras-like GTPases. Cell Signal. 1998;10:167–172. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(97)00120-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Michaelson D, et al. Postprenylation CAAX processing is required for proper localization of Ras but not Rho GTPases. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:1606–1616. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-11-0960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pegoraro AF, Janmey P, Weitz DA. Mechanical properties of the cytoskeleton and cells. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2017;9:a022038. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a022038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sen Gupta A, Sengupta K. Lamin B2 modulates nucleolar morphology, dynamics, and function. Mol Cell Biol. 2017;37:e00274-17. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00274-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coffinier C, et al. Abnormal development of the cerebral cortex and cerebellum in the setting of lamin B2 deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:5076–5081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908790107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burke B. On the cell-free association of lamins A and C with metaphase chromosomes. Exp Cell Res. 1990;186:169–176. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(90)90223-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xie W, et al. A-type lamins form distinct filamentous networks with differential nuclear pore complex associations. Curr Biol. 2016;26:2651–2658. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kolb T, Maass K, Hergt M, Aebi U, Herrmann H. Lamin A and lamin C form homodimers and coexist in higher complex forms both in the nucleoplasmic fraction and in the lamina of cultured human cells. Nucleus. 2011;2:425–433. doi: 10.4161/nucl.2.5.17765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eriksson M, et al. Recurrent de novo point mutations in lamin A cause Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Nature. 2003;423:293–298. doi: 10.1038/nature01629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fidziańska A, Toniolo D, Hausmanowa-Petrusewicz I. Ultrastructural abnormality of sarcolemmal nuclei in Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy (EDMD) J Neurol Sci. 1998;159:88–93. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(98)00130-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Denais CM, et al. Nuclear envelope rupture and repair during cancer cell migration. Science. 2016;352:353–358. doi: 10.1126/science.aad7297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raab M, et al. ESCRT III repairs nuclear envelope ruptures during cell migration to limit DNA damage and cell death. Science. 2016;352:359–362. doi: 10.1126/science.aad7611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stephens AD, et al. Chromatin histone modifications and rigidity affect nuclear morphology independent of lamins. Mol Biol Cell. 2018;29:220–233. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E17-06-0410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen NY, et al. Fibroblasts lacking nuclear lamins do not have nuclear blebs or protrusions but nevertheless have frequent nuclear membrane ruptures. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:10100–10105. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1812622115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dou Z, et al. Autophagy mediates degradation of nuclear lamina. Nature. 2015;527:105–109. doi: 10.1038/nature15548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vergnes L, Péterfy M, Bergo MO, Young SG, Reue K. Lamin B1 is required for mouse development and nuclear integrity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:10428–10433. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401424101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu J, Ma H, Liu Y. Stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM) Curr Protoc Cytom. 2017;81:12.46.1–12.46.27. doi: 10.1002/cpcy.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ma H, Xu J, Jin J, Huang Y, Liu Y. A simple marker-assisted 3D nanometer drift correction method for superresolution microscopy. Biophys J. 2017;112:2196–2208. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pageon SV, Nicovich PR, Mollazade M, Tabarin T, Gaus K. Clus-DoC: A combined cluster detection and colocalization analysis for single-molecule localization microscopy data. Mol Biol Cell. 2016;27:3627–3636. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E16-07-0478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nabbi A, Riabowol K. Rapid isolation of nuclei from cells in vitro. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2015;2015:769–772. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot083733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Otto H, Dreger M, Bengtsson L, Hucho F. Identification of tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins associated with the nuclear envelope. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:420–428. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2001.01901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.