Significance

Last year, 1.6 × 106 people died from tuberculosis (TB), and about 10 × 106 became infected with the causative bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis and 460,000 of them with multidrug-resistant bacteria. Bedaquiline, a new anti-TB drug, developed to combat multidrug-resistant TB, kills M. tuberculosis by preventing the operation of its molecular machine for generating adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the fuel of life, without affecting the equivalent human machine. Here, we describe the molecular structure of the module in the mycobacterial machine where ATP is generated. Differences between this module and the equivalent human module can now be exploited to develop new anti-TB drugs, unrelated to bedaquiline, that also may help to prevent and cure TB by inhibiting the formation of ATP.

Keywords: Mycobacterium smegmatis, F1-ATPase, structure, inhibition, tuberculosis

Abstract

The crystal structure of the F1-catalytic domain of the adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthase has been determined from Mycobacterium smegmatis which hydrolyzes ATP very poorly. The structure of the α3β3-component of the catalytic domain is similar to those in active F1-ATPases in Escherichia coli and Geobacillus stearothermophilus. However, its ε-subunit differs from those in these two active bacterial F1-ATPases as an ATP molecule is not bound to the two α-helices forming its C-terminal domain, probably because they are shorter than those in active enzymes and they lack an amino acid that contributes to the ATP binding site in active enzymes. In E. coli and G. stearothermophilus, the α-helices adopt an “up” state where the α-helices enter the α3β3-domain and prevent the rotor from turning. The mycobacterial F1-ATPase is most similar to the F1-ATPase from Caldalkalibacillus thermarum, which also hydrolyzes ATP poorly. The βE-subunits in both enzymes are in the usual “open” conformation but appear to be occupied uniquely by the combination of an adenosine 5′-diphosphate molecule with no magnesium ion plus phosphate. This occupation is consistent with the finding that their rotors have been arrested at the same point in their rotary catalytic cycles. These bound hydrolytic products are probably the basis of the inhibition of ATP hydrolysis. It can be envisaged that specific as yet unidentified small molecules might bind to the F1 domain in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, prevent ATP synthesis, and inhibit the growth of the pathogen.

In 2017, around 1.6 × 106 people died from tuberculosis (TB), and Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the causative bacterium, is now the second greatest killer of mankind by a single infectious agent, surpassed in its lethal impact only by human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (1). Of the 10 × 106 people estimated to have developed TB in that single year, 4.6% were resistant to both rifampicin and isoniazid and are classed as multidrug resistant (MDR), and 8.5% of the MDR-TB cases were extensively drug resistant (XDR). Only 55% of the MDR-TB and 30% of the XDR-TB cases were treated successfully. These alarming statistics serve to emphasize the urgent need to develop new drugs that are effective and fast acting against drug-resistant strains of M. tuberculosis. Preferably, they should be effective also against latent M. tuberculosis infections where the bacteria lie dormant in infected humans in a nonreplicating state before emerging as an active infection. It has been estimated that between a quarter and a third of the world’s population are latently infected (2). However, the impact of this latency has been questioned recently as nearly everyone who falls seriously ill with TB does so within 2 y of being infected, and latent infections rarely become active even in old age (3).

In 2012, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the use of a novel oral drug bedaquiline (SIRTURO) for the treatment of MDR-TB (4, 5), and bedaquiline received fast-track approval as a component of a combination therapy for treating MDR-TB in adults. Its potential to shorten dramatically the treatment time for MDR-TB is highlighted by two recent studies. In mouse models of TB, a combination of bedaquiline with PA-824, an antimycobacterial drug with a complex mode of action (6) and linezolid, a repurposed protein synthesis inhibitor, significantly improved efficacy and relapse rates compared with the frontline regimen of rifampicin, isoniazid, and pyrazinamide (7, 8). In the Nix-TB phase III clinical trial using this three-drug combination, 74% of the patients with MDR-TB were culture negative in 8 wk*. The most recent recommendations for the treatment of MDR-TB, based on the balance of effectiveness and harm and a preference for oral administration, now include bedaquiline (9). Bedaquiline is effective against both actively growing and nonreplicating cells of M. tuberculosis and acts by inhibiting the ATP synthase (10, 11) thereby shutting off the supply of cellular energy in the bacterium without noticeably affecting the human enzyme found in the inner membranes of the mitochondria. Thus, these observations provide proof of principle that the mycobacterial ATP synthase is a suitable target for developing new drugs to combat tuberculosis. A rational approach to the design of new drugs in addition to bedaquiline to inhibit the mycobacterial ATP synthase requires ideally that the structures and mechanistic and regulatory mechanisms of the human and mycobacterial ATP synthases be understood. The human enzyme is very similar in both respects to the well-studied bovine enzyme, which therefore provides an excellent surrogate. Mycobacterial ATP synthases have been less studied, and only the structure of the c ring in the membrane domain of the enzyme’s rotor in the enzyme from the nonpathogenic organism Mycobacterium phlei has been established (12). It is here that bedaquiline binds (12), presumably impeding the turning of the rotor in the intact enzyme. It has been proposed that it also binds at a secondary site in the ε-subunit (13, 14). Before, the work described here, the structure of its F1-catalytic domain was not known in any mycobacterial ATP synthase, and there was no molecular understanding of why the mycobacterial enzymes are barely capable of hydrolyzing ATP (15), whereas, for example, the enzymes from facultative anaerobes, such as Escherichia coli can both synthesize and hydrolyze ATP. Here, we describe the structure of the inhibited state of the catalytic domain of the ATP synthase from another nonpathogenic Mycobacterium, Mycobacterium smegmatis. It is an excellent surrogate for the catalytic domain of the F1-ATPase from M. tuberculosis as a comparison of the sequences of the subunits from various mycobacterial species demonstrates (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 and Table S1).

Results and Discussion

Characterization of F1-ATPase from M. smegmatis.

The nine subunits of the ATP synthase in M. smegmatis are encoded by the atp operon, which includes the cluster of genes atpAGDC encoding the constituent α-, γ-, β-, and ε-subunits, respectively, of the F1-ATPase complex. This cluster was amplified by the polymerase chain reaction, modified to encode the N terminus of the β-subunit fused to a hexahistidine tag with an intervening protease cleavage site, and the vector containing the four genes was introduced into M. smegmatis. Attempts to overexpress the M. tuberculosis orthologs in M. smegmatis in the same way failed as the genes from the two mycobacterial species recombined. The overexpressed purified F1-ATPase (SI Appendix, Fig. S2) was a single complex with a mass of 380 kDa, composed of the expected complement of α-, β-, γ-, and ε-subunits with their characteristic molecular masses (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 and Table S2). It had a very low ATP hydrolase activity (0.07 U/mg), and, in contrast to some other latent F1-ATPases, for example, the enzyme from Caldalkalibacillus thermarum (16), this low activity could not be stimulated by lauryldimethylamine oxide (LDAO). However, when the mycobacterial enzyme was treated briefly with trypsin, the specific activity increased by 100-fold to 7 U/mg. Although characterization of the proteolytic fragments (SI Appendix, Table S3) did not provide a clear indication of the mechanism of activation, it is worth noting that the ε-subunit had been degraded almost completely after 2 min with a corresponding significant increase in activity. In E. coli F1-ATPase and F1Fo-ATPase from M. smegmatis, activation by trypsinolysis has been attributed to removal of the ε-subunit (17). The activity of F1-ATPase from M. smegmatis uncovered by trypsinolysis was doubled by the addition of LDAO (SI Appendix, Fig. S4).

Structure Determination.

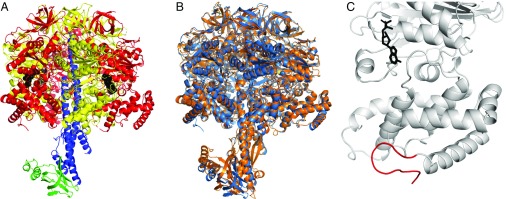

Hexagonal crystals of the complex containing all four subunits (SI Appendix, Fig. S5) have the unit-cell parameters a = b = 105.2, c = 628.6 Å with α = β = 90.0° and γ = 120.0° and belong to space group P3121 with one F1-ATPase in the asymmetric unit (see SI Appendix, Table S4 for a summary of data collection and refinement statistics). The quality of the electron density map is indicated in SI Appendix, Fig. S6 where representative segments and their interpretation are shown. The structure (Fig. 1A) contains the following residues: αE, 31–190, 202–511, and 1512–1522 (corresponding to the C-terminal extension where the register is unclear. Here, the residue numbers have been increased by 1,000 to indicate uncertainty as required by the PDB); αTP, 30–190, 202–406, and 414–511; αDP, 30–190, 202–409, and 412–511; βE, 9–41, 47–108, 116–132, and 136–471; βTP, 8–41, 47–108, and 114–471; βDP, 9–41, 47–108, and 116–471; γ, 4–57, 84–108, 119–129, 139–163, 188–198, and 238–304; ε, 3–115. Overall, the structure is similar to those of F1-ATPases determined previously in other species (SI Appendix, Fig. S7 and Table S5) and especially to the F1-ATPase from C. thermarum (18) (Fig. 1B). Although the structures of the αE-, αTP-, and αDP-subunits terminate at residue 511, the sequences of the subunits extend to residue 548. This C-terminal extension is characteristic of α-subunits in mycobacteria and is not found in other eubacterial, chloroplast, or mitochondrial sequences (SI Appendix, Fig. S8). By two independent programs, this extension is predicted to be intrinsically disordered (SI Appendix, Fig. S9), and it was possible to build a segment of 10 residues of extended structure immediately following the C-terminal α-helix of the αE-subunit (Fig. 1C). However, the sequence register could not be determined unambiguously, and so this segment is modeled as unknown and numbered 1512–1522. In a peptide representing residues 521–540, it has been shown by solution nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) that residues 526–539 are α-helical (but no coordinates are available) and on the basis of structure prediction that this α-helical structure prevailed in the intact protein (19). However, the current prediction of intrinsic disorder in the entire C-terminal region from residues 512–548 (SI Appendix, Fig. S9) and the secondary structures of the subunit in seven mycobacterial species predicted with the program PSIPRED (20) (SI Appendix, Fig. S10) are not in accord with this proposal. Another program, Predator (21), used previously (19), gives an ambiguous answer, predicting an α-helix in the region of residues 530–540 in four out of the seven species including M. tuberculosis but not M. smegmatis (SI Appendix, Fig. S10), M. phlei, or Mycobacterium ulcerans. In conclusion, on the basis of the current structure predictions (and acknowledging that NMR studies show that residues 526–539 in the isolated segment from residues 521–540 are α-helical), it appears on balance to be unlikely that an α-helix forms in this region of the intact α-subunit. Nonetheless, it remains possible that this additional region of the mycobacterial subunits could play a role in the regulation of the enzyme (19).

Fig. 1.

The structure of the F1-ATPase from M. smegmatis. (A) Side view in ribbon representation with the α-, β-, γ-, and ε-subunits in red, yellow, blue, and green, respectively, and bound nucleotides in black. (B) Comparison of the F1-ATPase complexes from M. smegmatis (sky blue) and C. thermarum (18) (orange). The structures were superimposed via their α3β3-domains. (C) The C-terminal extension in the αE-subunit of F1-ATPase from M. smegmatis. Density extending from the C-terminal helix (residues 494–511) was modeled from residues 1512–1522 (red), but the register is uncertain, and the following 27 residues are unresolved. An adenosine 5′-diphosphate (ADP) molecule (black) is shown bound to the nucleotide binding site.

The α3β3-Domain.

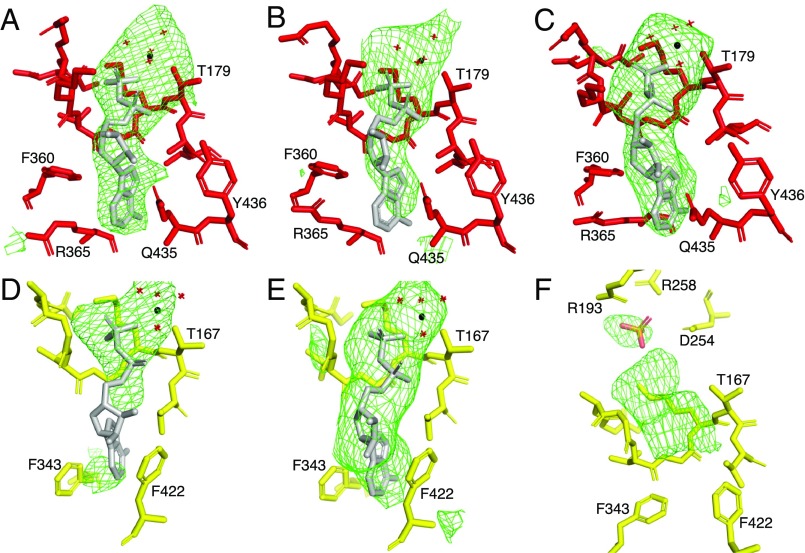

In the nucleotide binding sites of the three α-subunits and the βTP-subunit, additional electron density is compatible with them being occupied by an ADP molecule plus a magnesium ion (Fig. 2). There is also additional electron density associated with the nucleotide binding sites in both the βDP- and the βE-subunits. Although the additional density is discontinuous in the former, it can be interpreted plausibly as ADP plus a magnesium ion. In the latter site, the additional density is associated with the region of the phosphate-binding loop (P-loop) where the α- and β-phosphates of a nucleotide would be bound as, for example, in the βE-subunit of the F1-ATPase from C. thermarum (18) (where an ADP molecule with no magnesium ion is bound at 50–100% occupancy when crystals are grown in the presence of 500 µM ADP). Both the ADP and a single phosphate ion were tested near the P-loop at various occupancies, but neither refined well into this site. However, there is, also additional density above the P-loop where a phosphate ion has been modeled as in the βE-subunit of the C. thermarum enzyme where a phosphate ion sits above the ADP. Although this density has been modeled as a phosphate, it could possibly be a sulfate introduced from the crystallization buffer. Superimposition of the structures of the F1-ATPases from M. smegmatis and C. thermarum via their α3β3-domains showed that the two structures are very similar [root-mean-square deviation (rmsd) value of 0.91 Å]. The occupancy of nucleotide binding sites in the C. thermarum enzyme is ADP and a magnesium ion in the three α-subunits and in the βTP- and βDP-subunits and ADP and a phosphate without a magnesium ion in the βE-subunit. Therefore, although the additional density in the P-loop region of the βE-subunit in the M. smegmatis enzyme remains uninterpreted, the close similarity of the structure to the structure of the inhibited complex in C. thermarum suggests that the site is probably occupied by an ADP molecule (with no accompanying magnesium ion) at low occupancy.

Fig. 2.

Occupancy of nucleotide binding sites in the α- and β-subunits of the F1-ATPase from M. smegmatis. A Fo-Fc difference density map was calculated for the complex with the nucleotides, phosphate, Mg2+, and water molecules at zero occupancy. The difference density is shown as green mesh contoured to 2.5 σ. (A–C) The αDP-, αTP-, and αE-subunits; (D–F) the βDP-, βTP-, and βE-subunits. In (A–E), the sites are occupied by ADP and an accompanying magnesium ion (black sphere) with four water ligands (red crosses); the fifth and sixth ligands are provided by O2B of the ADP and the hydroxyl of either αThr-179 or βThr-167. In (F), the upper region of the catalytic site is occupied by a phosphate (or sulfate) ion (orange and red). Although the electron density beneath it in the vicinity of the P-loop cannot be interpreted with confidence, it probably can be accounted for by an ADP molecule (without a magnesium ion) at partial occupancy.

The γ-Subunit.

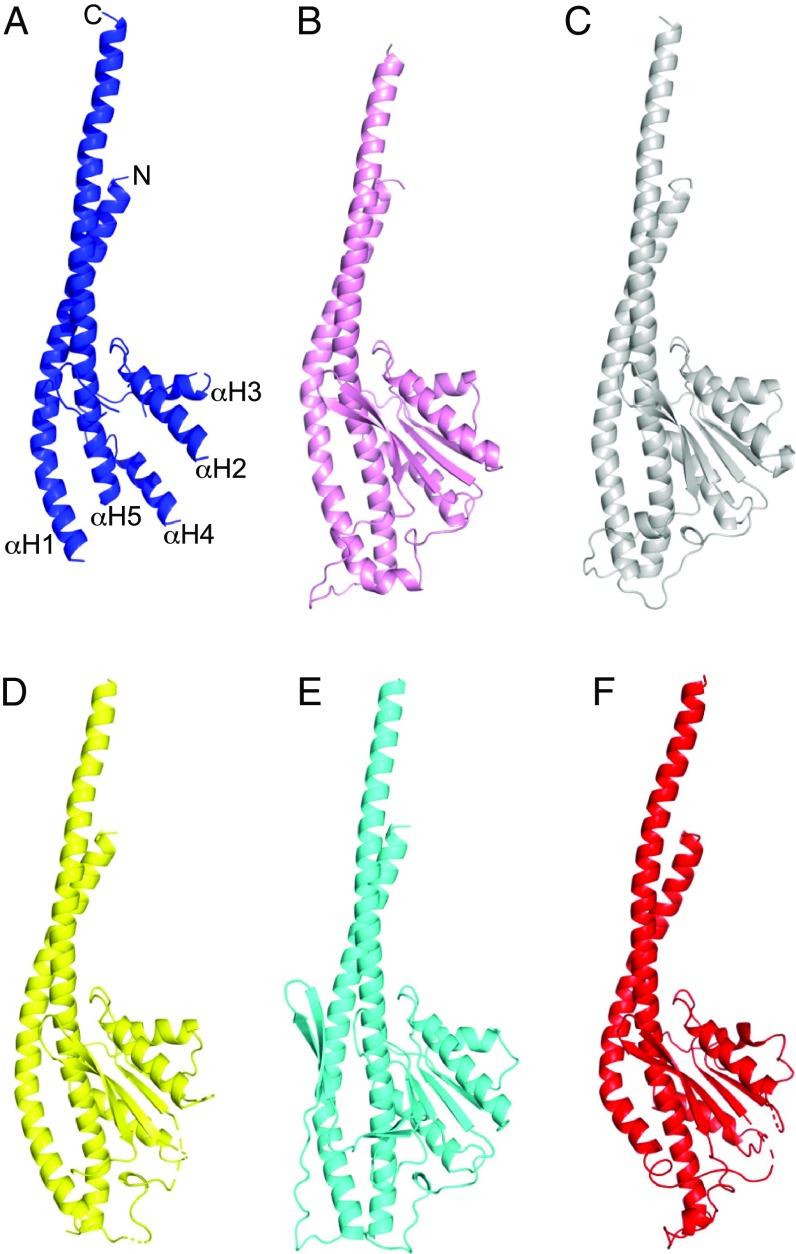

The structure of the γ-subunit is the least well resolved of the eight constituent subunits of the enzyme, probably because it is not constrained by any contacts with other F1-ATPase complexes in the crystal lattice. In C. thermarum, for example, where the subunit is constrained in the crystal lattice, it is resolved entirely apart from residues 1–3. The C. thermarum subunit is folded into two α-helices in its N- and C-terminal regions with an intervening Rossmann fold as in other species that have been studied (Fig. 3) (18, 22–25). The N- and C-terminal α-helices make an antiparallel coiled coil occupying the central axis of the α3β3-domain, and the Rossmann fold has five β-strands with α-helices among strands 1 and 2, 2 and 3, and 3 and 4. In the mycobacterial enzyme, the N- and C-terminal α-helices are well resolved except for approximately three α-helical turns at the N terminus of the C-terminal α-helix. The intervening α-helices 2, 3, and 4 were also resolved, but none of the five β-strands and connecting loops in the Rossmann fold could be built. However, superposition of the fragmentary structure of the mycobacterial γ-subunit upon the C. thermarum γ-subunit is consistent with the structures of the two orthologs being closely similar. This structural similarity extends to the γ-subunits from E. coli (22), P. denitrificans (23), and spinach chloroplasts (24) (Fig. 3). The overall fold of these γ-subunits is also similar to the γ-subunits from the enzymes from bovine (25) (Fig. 3) and yeast (26) mitochondria except that the N-terminal α-helices of the bacterial γ-subunits extend further in the C-terminal direction and they are less curved. However, the γ-subunits of the M. smegmatis and C. thermarum enzymes have an additional highly significant similarity that distinguishes them from the γ-subunits in the other F1-ATPases and supports the view that the two determined structures represent the same inhibited state of the enzyme. In the M. smegmatis and C. thermarum γ-subunits, residues 22–33, the “rigid-body” regions (see Materials and Methods) are rotated approximately to the same extent (10.5° in M. smegmatis, and 9° and 13° in the two copies in the asymmetric unit of the crystals of the C. thermarum enzyme, respectively), whereas the rotation angles in the E. coli, P. denitrificans, and spinach chloroplast enzymes, which have different nucleotide occupancies in their catalytic sites to the C. thermarum enzyme, are 50°, 27°, and 22°, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the structure of the γ-subunits of the F-ATPases from M. smegmatis with those of the orthologs. (A) M. smegmatis with the five α-helices numbered 1–5 from the N to the C terminus; (B) E. coli (22); (C) C. thermarum (18); (D) Paracoccus denitrificans (23); (E) chloroplast from spinach (24); (F) bovine mitochondria (25).

A feature, discussed before, that distinguishes mycobacterial γ-subunits from nonmycobacterial species that might be a target for drug design, is that 12–14 amino acids are inserted in the region from residues 165–169 in the aligned sequences (SI Appendix, Fig. S11). This insertion is at the C terminus of α-helix 4 (Fig. 3A) and is predicted to form a random coil (SI Appendix, Fig. S12) that might extend to the bacterial membrane surface (27). As this region is unresolved, it is not known whether this suggestion is correct.

The ε-Subunit.

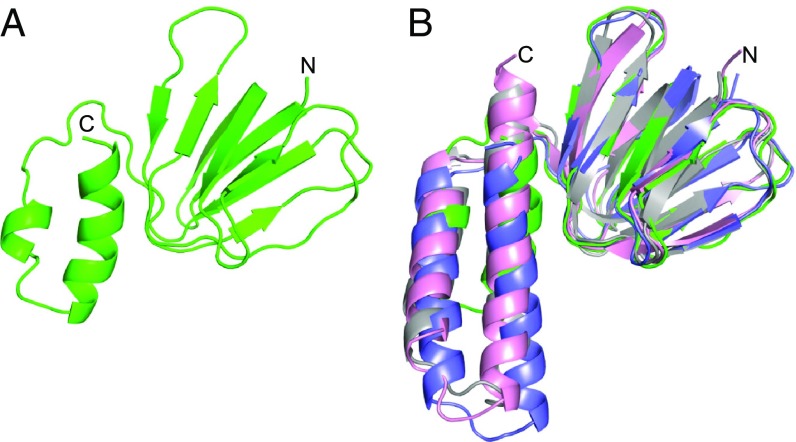

As in ATP synthases from other eubacteria, chloroplasts, and mitochondria (where the orthologous protein is known as the δ-subunit) (28), the M. smegmatis ε-subunit has two domains (Fig. 4). The N-terminal domain is folded into an eight-stranded β-sandwich and is very similar to those in other species. For example, the rmsd values for the comparisons of the N-terminal domain of the ε-subunit from M. smegmatis with those from E. coli and C. thermarum are 1.2 and 1.0 Å, respectively. In contrast, the C-terminal domain differs substantially from those in the orthologs. In E. coli, C. thermarum, G. stearothermophilus, and in bovine and yeast mitochondria, this region is folded into two α-helices, ∼23 and 30 Å long. In E. coli (22, 29–32) and G. stearothermophilus (33–35), the α-helices adopt two different states, referred to as “down” and “up.” In the down state of the F-ATPase from G. stearothermophilus (35), the α-helices of the ε-subunit bind an ATP molecule and are associated with the β-sandwich. In the absence of bound ATP, the α-helices assume the up position where they lie alongside the γ-subunit and interact with the α3β3-domain, inhibiting ATP hydrolysis. Up positions have been captured in structures of the F1-domain from E. coli (22) and in the intact E. coli ATP synthase complex (32), but the isolated E. coli ε-subunit adopts a down conformation, although ATP is not bound to it suggesting that ATP does not influence the position of the ε-subunit (29–31). In the F1-ATPase from C. thermarum, even in the absence of a bound ATP molecule, the α-helices remain in the down position, and the up state has not been observed (18). In mitochondria, the two C-terminal α-helices of the orthologous δ-subunit are also permanently down, and the site where the ATP molecule is bound in E. coli, G. stearothermophilus, and C. thermarum and is occupied by the single α-helix of a small protein not found in bacteria and chloroplasts, known confusingly as the ε-subunit (25). In the mycobacterial ε-subunits, the sequences of their C-terminal regions are shorter than in the other species where the structure of the subunit is known, and in the M. smegmatis ε-subunit, a C-terminal α-helical hairpin also forms next to the N-terminal domain in the down state, but the α-helices are truncated relative to E. coli, G. stearothermophilus, and C. thermarum. However, despite the shorter α-helical hairpin in the M. smegmatis ε-subunit, the general appearance of the interaction of the truncated C-terminal α-helix with the N-terminal domain of the protein is conserved (Fig. 4B) as are the number of interactions (eight in each case) and their approximate positions in the N- and C-terminal domains, although none of the side chains of these residues are conserved significantly in M. smegmatis (SI Appendix, Fig. S13). Furthermore, there is no evidence of an ATP molecule bound to the subunit. This was anticipated as Arg-94, one of the key residues involved in binding the nucleotide in E. coli, G. stearothermophilus, and C. thermarum is substituted in the equivalent site by an alanine residue in M. smegmatis (SI Appendix, Fig. S13), and superposition of the M. smegmatis and E. coli F1-ATPases demonstrated that the former ε-subunit cannot assume the up position in the structure of the inhibited enzyme as its C-terminal α-helix would clash with the DELSEED region in the C-terminal domain of the βDP-subunit (SI Appendix, Fig. S14). Moreover, there is no evidence for the presence of the up state in the current electron density map, and in an NMR structure of the isolated ε-subunit from M. smegmatis the protein is in the down position (14). This structure resembles the ε-subunit described here, but as the deposited coordinates have not been released, a precise comparison with the current structure is not possible. Thus, there is currently no structural evidence that the ε-subunit plays a role in the regulation of the hydrolytic activity of the M. smegmatis ATP synthase complex.

Fig. 4.

The structure of the ε-subunit of the F1-ATPase from M. smegmatis compared with the orthologs. (A) The mycobacterial ε-subunit showing the N-terminal β-sandwich and the C-terminal α-helical domains; (B) superimposition of the ε-subunits from M. smegmatis (green), C. thermarum (18) (gray), E. coli (29) (pink), and the bovine δ-subunit (25) (slate blue). The N-terminal domains are very similar, but both C-terminal helices of the M. smegmatis protein are shorter than in the other examples.

Regulation of ATP Hydrolysis.

It is becoming clear that a variety of mechanisms operates to regulate the ATP hydrolytic activity of ATP synthases in eubacteria, mitochondria, and chloroplasts. In α-proteobacteria, exemplified by P. denitrificans, ATP hydrolysis appears to be inhibited by a protein called the ζ-subunit (23, 36) where the N-terminal inhibitory region binds to a catalytic interface under hydrolytic conditions in a closely related fashion to the inhibitory action of the orthologous mitochondrial inhibitory protein IF1 on the mitochondrial ATP synthase (37–39). In the case of mammalian IF1, inhibition of ATP hydrolysis of the protein is activated by a fall in the pH (40), such as would occur in the mitochondrial matrix accompanying an increased reliance by cells on the provision of ATP by glycolysis. In the chloroplasts of green plants and algae, during the hours of darkness when the proton motive force is low, ADP-Mg remains bound to one of the three catalytic sites of the enzyme forming an inactive ADP inhibited state of the enzyme (41, 42). This inhibited state is stabilized by the formation of an intermolecular disulfide bond in the γ-subunit of the enzyme. The formation of this disulfide is proposed to stabilize a β-hairpin structure formed by a unique additional sequence in the γ-subunit (residues 198–233 in SI Appendix, Fig. S11; see SI Appendix, Fig. S15) that wedges between the β-subunit and the central stalk thereby blocking the rotation of the γ-subunit and preventing futile ATP hydrolysis (43). With daylight and a rising proton motive force, the synthetic activity of the enzyme is restored by reduction of the disulfide bond by thioredoxin. The γ-subunits in cyanobacterial ATP synthases also contain a related insertion (44), but it lacks the nine residue sequence containing the two cysteine residues (SI Appendix, Fig. S11), and, although the residual additional loop appears to inhibit ATP hydrolysis, it is not regulated by the redox mechanism found in chloroplasts (45).

The ATPases in the aerobic bacterium G. stearothermophilus (35) and in the facultative anaerobe E. coli (22, 32, 46) appear to be regulated by their ε-subunit. For G. stearothermophilus, it has been proposed that, when the proton-motive force and ATP concentration are low, this ATP molecule is released from the ε-subunit, allowing its two C-terminal α-helices to assume the up inhibitory position where they penetrate into a catalytic site alongside the rotary γ-subunit and impede the turning of the rotor (33, 47, 48). However, there is no evidence for the operation of a similar inhibitory mechanism in the thermoalkaliphile C. thermarum where it appears that ATP hydrolysis is prevented either by the failure to release the products of ATP hydrolysis from one catalytic site or, less likely, for those products to be released and rebound (18).

A characteristic feature of bacterial F-ATPases with latent hydrolytic activity is that ATP hydrolysis can be activated artificially in vitro. For example, LDAO activates the hydrolytic activity of F1-ATPase from C. thermarum 30-fold, and maximum activation was achieved by the removal of the C-terminal domain of the ε-subunit (49). The hydrolytic activity of this enzyme is not activated by proteolysis, and its ε-subunit is resistant to such treatment (49). In contrast, the F1-ATPase from M. smegmatis is activated by trypsinolysis, and its activity is stimulated further by the addition of LDAO. However, it is not activated by LDAO before trypsinolysis has taken place (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). In other bacterial species, the activation of hydrolytic activity by LDAO activation has been attributed to either release of an ADP molecule from a catalytic site (50, 51) or perturbation of the interaction between the ε-subunit and the α3β3-domain (52). However, the molecular basis of the activation of the hydrolytic activity of F1-ATPases by trypsinolysis and/or LDAO, including the enzyme from M. smegmatis, remains unclear.

The current structure of the F1-ATPase from M. smegmatis, albeit at modest resolution, is very similar to that of the inhibited complex from C. thermarum in terms of the protein structure itself (apart from the C-terminal extension of the α-subunits, which could also be involved in regulation of ATP hydrolysis). Especially, the rotational state of the γ-subunit suggests that the ATP hydrolytic activities of the two enzymes have been arrested at the same point in the rotary cycle. In C. thermarum, phosphate and ADP (at 50–70% occupancy) without a magnesium ion are bound to the site (18), whereas the occupancy of the βE-subunit in the M. smegmatis enzyme is likely to be similar. The order of release of the products of ATP hydrolysis by F-ATPases has not been established firmly, although it appears that the magnesium ion leaves first as the catalytic site opens (18, 26, 53, 54). The data about whether the subsequent release of ADP precedes that of phosphate are conflicting (26, 53–58), although in other NTPases, phosphate leaves first (59–61). The current structure of the F1-ATPase from M. smegmatis can be interpreted as being consistent with such an order.

Mycobacteria are obligate aerobes with an extraordinary ability to survive for prolonged periods of hypoxia. A key element of their survival is their ability to keep their respiratory chain energized and thereby to maintain their energy requirements by continuing to make ATP (62, 63). The membrane potential used by mycobacteria to drive ATP synthesis under hypoxia is low (−65 to −75 mV) (62, 63), and they are faced with the thermodynamic challenge of inhibiting ATPase activity while at the same time remaining competent for ATP synthesis. If the ATP synthase were freely reversible, the cells would become depleted of ATP rapidly to reestablish the membrane potential, and they would die. Thus, the extreme latency of the enzyme in the direction of ATP hydrolysis is a characteristic feature of ATP synthases from fast and slow growing mycobacteria (15), and the mechanism of ATP inhibition is an intrinsic feature of the F1-domain. The structure of the mycobacterial F1-domain reported here is a big step toward uncovering the molecular basis of this inhibitory mechanism, and it provides a framework for the structure-based design of a small molecule that might activate ATP hydrolysis or inhibit ATP synthesis specifically in the pathogen.

Materials and Methods

The F1-ATPase from M. smegmatis (subunits α, β, γ, and ε) was overexpressed from a plasmid in the M. smegmatis strain mc2 4517, purified by nickel affinity chromatography via a His6-tag attached to the β-subunit, size exclusion chromatography, crystallized by vapor diffusion, and its structure solved from X-ray diffraction data by molecular replacement with the F1-ATPase from C. thermarum (PDB5hkk). Images of the structures and electron density maps were prepared with PyMOL (64). For further details, see the SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Medical Research Council, U.K. by Grants MC_U105663150 and MR/M009858/1 (to J.E.W.) and MC_U105184325 (to A.G.W.L.) and by the European Drug Initiative on Channels and Transporters (EDICT) via Contract HEALTH-F4-2007-201924 (to J.E.W.). G.M.C. was supported by a James Cook Fellowship from The Royal Society of New Zealand. We thank the beamline staff at the Swiss Light Source, the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility and at beamline I04, the Diamond Light Source for their help, and Dr. I. M. Fearnley and Dr. S. Ding for recording mass spectra.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.wwpdb.org (PDB ID code 6FOC).

*Conradie F, et al. (2017) The NIX-TB trial of pretomanid, bedaquiline and linezoid to treat XDR-TB. Conference on RetroViruses and Opportunistic Infections 2017, Seattle, abstr 80LB.

See Commentary on page 3956.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1817615116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.World Health Organization 2018 Global tuberculosis report 2018. Available at https://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/. Accessed September 18, 2018.

- 2.Houben RM, Dodd PJ. The global burden of latent tuberculosis infection: A Re-estimation using mathematical modelling. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1002152. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Behr MA, Edelstein PH, Ramakrishnan L. Revisiting the timetable of tuberculosis. BMJ. 2018;362:k2738. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k2738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diacon AH, et al. Randomized pilot trial of eight weeks of bedaquiline (TMC207) treatment for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: Long-term outcome, tolerability, and effect on emergence of drug resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:3271–3276. doi: 10.1128/AAC.06126-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diacon AH, et al. TMC207-C208 Study Group Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis and culture conversion with bedaquiline. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:723–732. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1313865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manjunatha U, Boshoff HI, Barry CE. The mechanism of action of PA-824: Novel insights from transcriptional profiling. Commun Integr Biol. 2009;2:215–218. doi: 10.4161/cib.2.3.7926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tasneen R, et al. Contribution of the nitroimidazoles PA-824 and TBA-354 to the activity of novel regimens in murine models of tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:129–135. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03822-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tasneen R, et al. Contribution of oxazolidinones to the efficacy of novel regimens containing bedaquiline and pretomanid in a mouse model of tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;60:270–277. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01691-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization 2018 Rapid communication: Key changes to treatment of multidrug- and rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis (MDR/RR-TB). Available at https://www.who.int/tb/publications/2018/rapid_communications_MDR/en/. Accessed December 17, 2018.

- 10.Andries K, et al. A diarylquinoline drug active on the ATP synthase of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science. 2005;307:223–227. doi: 10.1126/science.1106753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koul A, et al. Delayed bactericidal response of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to bedaquiline involves remodelling of bacterial metabolism. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3369. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Preiss L, et al. Structure of the mycobacterial ATP synthase Fo rotor ring in complex with the anti-TB drug bedaquiline. Sci Adv. 2015;1:e1500106. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1500106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kundu S, Biukovic G, Grüber G, Dick T. Bedaquiline targets the ε subunit of mycobacterial F-ATP synthase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60:6977–6979. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01291-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joon S, et al. The NMR solution structure of Mycobacterium tuberculosis F-ATP synthase subunit ε provides new insight into energy coupling inside the rotary engine. FEBS J. 2018;285:1111–1128. doi: 10.1111/febs.14392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haagsma AC, Driessen NN, Hahn MM, Lill H, Bald D. ATP synthase in slow- and fast-growing mycobacteria is active in ATP synthesis and blocked in ATP hydrolysis direction. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2010;313:68–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.02123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cook GM, et al. Purification and biochemical characterization of the F1Fo-ATP synthase from thermoalkaliphilic Bacillus sp. strain TA2.A1. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:4442–4449. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.15.4442-4449.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gavilanes-Ruiz M, Tommasino M, Capaldi RA. Structure-function relationships of the Escherichia coli ATP synthase probed by trypsin digestion. Biochemistry. 1988;27:603–609. doi: 10.1021/bi00402a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferguson SA, Cook GM, Montgomery MG, Leslie AGW, Walker JE. Regulation of the thermoalkaliphilic F1-ATPase from Caldalkalibacillus thermarum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:10860–10865. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1612035113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ragunathan P, et al. The uniqueness of subunit α of mycobacterial F-ATP synthases: An evolutionary variant for niche adaptation. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:11262–11279. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.784959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buchan DW, Minneci F, Nugent TC, Bryson K, Jones DT. Scalable web services for the PSIPRED protein analysis workbench. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:W349–W357. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frishman D, Argos P. Incorporation of non-local interactions in protein secondary structure prediction from the amino acid sequence. Protein Eng. 1996;9:133–142. doi: 10.1093/protein/9.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cingolani G, Duncan TM. Structure of the ATP synthase catalytic complex (F(1)) from Escherichia coli in an autoinhibited conformation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:701–707. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morales-Rios E, Montgomery MG, Leslie AGW, Walker JE. Structure of ATP synthase from Paracoccus denitrificans determined by X-ray crystallography at 4.0 Å resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:13231–13236. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1517542112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hahn A, Vonck J, Mills DJ, Meier T, Kühlbrandt W. Structure, mechanism, and regulation of the chloroplast ATP synthase. Science. 2018;360:eaat4318. doi: 10.1126/science.aat4318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gibbons C, Montgomery MG, Leslie AGW, Walker JE. The structure of the central stalk in bovine F(1)-ATPase at 2.4 A resolution. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:1055–1061. doi: 10.1038/80981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kabaleeswaran V, Puri N, Walker JE, Leslie AGW, Mueller DM. Novel features of the rotary catalytic mechanism revealed in the structure of yeast F1 ATPase. EMBO J. 2006;25:5433–5442. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Priya R, et al. Solution structure of subunit γ (γ(1-204)) of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis F-ATP synthase and the unique loop of γ(165-178), representing a novel TB drug target. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2013;45:121–129. doi: 10.1007/s10863-012-9486-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walker JE, Runswick MJ, Saraste M. Subunit equivalence in Escherichia coli and bovine heart mitochondrial F1F0 ATPases. FEBS Lett. 1982;146:393–396. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(82)80960-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uhlin U, Cox GB, Guss JM. Crystal structure of the ε subunit of the proton-translocating ATP synthase from Escherichia coli. Structure. 1997;5:1219–1230. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00272-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilkens S, Dahlquist FW, McIntosh LP, Donaldson LW, Capaldi RA. Structural features of the ε subunit of the Escherichia coli ATP synthase determined by NMR spectroscopy. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2:961–967. doi: 10.1038/nsb1195-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilkens S, Capaldi RA. Solution structure of the ε subunit of the F1-ATPase from Escherichia coli and interactions of this subunit with β subunits in the complex. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:26645–26651. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sobti M, et al. Cryo-EM structures of the autoinhibited E. coli ATP synthase in three rotational states. eLife. 2016;5:e21598. doi: 10.7554/eLife.21598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yagi H, et al. Structures of the thermophilic F1-ATPase ε subunit suggesting ATP-regulated arm motion of its C-terminal domain in F1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:11233–11238. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701045104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kato S, Yoshida M, Kato-Yamada Y. Role of the ε subunit of thermophilic F1-ATPase as a sensor for ATP. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:37618–37623. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707509200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shirakihara Y, et al. Structure of a thermophilic F1-ATPase inhibited by an ε-subunit: Deeper insight into the ε-inhibition mechanism. FEBS J. 2015;282:2895–2913. doi: 10.1111/febs.13329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morales-Ríos E, et al. A novel 11-kDa inhibitory subunit in the F1FO ATP synthase of Paracoccus denitrificans and related α-proteobacteria. FASEB J. 2010;24:599–608. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-137356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gledhill JR, Montgomery MG, Leslie AGW, Walker JE. How the regulatory protein, IF(1), inhibits F(1)-ATPase from bovine mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15671–15676. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707326104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robinson GC, et al. The structure of F1-ATPase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae inhibited by its regulatory protein IF1. Open Biol. 2013;3:120164. doi: 10.1098/rsob.120164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bason JV, Montgomery MG, Leslie AGW, Walker JE. Pathway of binding of the intrinsically disordered mitochondrial inhibitor protein to F1-ATPase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:11305–11310. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1411560111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cabezon E, Butler PJ, Runswick MJ, Walker JE. Modulation of the oligomerization state of the bovine F1-ATPase inhibitor protein, IF1, by pH. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:25460–25464. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003859200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nalin CM, McCarty RE. Role of a disulfide bond in the γ subunit in activation of the ATPase of chloroplast coupling factor 1. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:7275–7280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ketcham SR, Davenport JW, Warncke K, McCarty RE. Role of the gamma subunit of chloroplast coupling factor 1 in the light-dependent activation of photophosphorylation and ATPase activity by dithiothreitol. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:7286–7293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murakami S, et al. Structure of the γ-ε complex of cyanobacterial F1-ATPase reveals a suppression mechanism of the γ subunit on ATP hydrolysis in phototrophs. Biochem J. 2018;475:2925–2939. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20180481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cozens AL, Walker JE. The organization and sequence of the genes for ATP synthase subunits in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus 6301. Support for an endosymbiotic origin of chloroplasts. J Mol Biol. 1987;194:359–383. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90667-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Werner S, Schumann J, Strotmann H. The primary structure of the gamma-subunit of the ATPase from Synechocystis 6803. FEBS Lett. 1990;261:204–208. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80671-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shah NB, Hutcheon ML, Haarer BK, Duncan TM. F1-ATPase of Escherichia coli: The ε- inhibited state forms after ATP hydrolysis, is distinct from the ADP-inhibited state, and responds dynamically to catalytic site ligands. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:9383–9395. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.451583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Feniouk BA, Suzuki T, Yoshida M. Regulatory interplay between proton motive force, ADP, phosphate, and subunit epsilon in bacterial ATP synthase. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:764–772. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606321200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Suzuki T, et al. F0F1-ATPase/synthase is geared to the synthesis mode by conformational rearrangement of ε subunit in response to proton motive force and ADP/ATP balance. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:46840–46846. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307165200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Keis S, Stocker A, Dimroth P, Cook GM. Inhibition of ATP hydrolysis by thermoalkaliphilic F1Fo-ATP synthase is controlled by the C terminus of the epsilon subunit. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:3796–3804. doi: 10.1128/JB.00040-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Paik SR, Jault JM, Allison WS. Inhibition and inactivation of the F1 adenosinetriphosphatase from Bacillus PS3 by dequalinium and activation of the enzyme by lauryl dimethylamine oxide. Biochemistry. 1994;33:126–133. doi: 10.1021/bi00167a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jault JM, et al. The α3β3γ complex of the F1-ATPase from thermophilic Bacillus PS3 containing the αD261N substitution fails to dissociate inhibitory MgADP from a catalytic site when ATP binds to noncatalytic sites. Biochemistry. 1995;34:16412–16418. doi: 10.1021/bi00050a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dunn SD, Tozer RG, Zadorozny VD. Activation of Escherichia coli F1-ATPase by lauryldimethylamine oxide and ethylene glycol: Relationship of ATPase activity to the interaction of the ε and β subunits. Biochemistry. 1990;29:4335–4340. doi: 10.1021/bi00470a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rees DM, Montgomery MG, Leslie AGW, Walker JE. Structural evidence of a new catalytic intermediate in the pathway of ATP hydrolysis by F1-ATPase from bovine heart mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:11139–11143. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207587109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bason JV, Montgomery MG, Leslie AGW, Walker JE. How release of phosphate from mammalian F1-ATPase generates a rotary substep. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:6009–6014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1506465112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Watanabe R, Iino R, Noji H. Phosphate release in F1-ATPase catalytic cycle follows ADP release. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:814–820. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Okazaki K, Hummer G. Phosphate release coupled to rotary motion of F1-ATPase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:16468–16473. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305497110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Watanabe R, Noji H. Timing of inorganic phosphate release modulates the catalytic activity of ATP-driven rotary motor protein. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3486. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nam K, Pu J, Karplus M. Trapping the ATP binding state leads to a detailed understanding of the F1-ATPase mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:17851–17856. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1419486111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gulick AM, Rayment I. Structural studies on myosin II: Communication between distant protein domains. BioEssays. 1997;19:561–569. doi: 10.1002/bies.950190707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wittinghofer A, Vetter IR. Structure-function relationships of the G domain, a canonical switch motif. Annu Rev Biochem. 2011;80:943–971. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-062708-134043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Milic B, Andreasson JO, Hancock WO, Block SM. Kinesin processivity is gated by phosphate release. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:14136–14140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1410943111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rao SP, Alonso S, Rand L, Dick T, Pethe K. The protonmotive force is required for maintaining ATP homeostasis and viability of hypoxic, nonreplicating Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:11945–11950. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711697105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Berney M, Cook GM. Unique flexibility in energy metabolism allows mycobacteria to combat starvation and hypoxia. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8614. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schrödinger, LLC 2018. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System (Schrödinger, LLC, New York), Version 2.2.2.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.