Significance

Bladder cancer poses a big clinical challenge, particularly in advanced cases. Here we present a culture system for bladder cancer based on organoid culture technology. We have created a living biobank containing organoids grown from over 50 patient samples, which reflects many aspects of bladder cancer pathogenesis. Organoids of human bladder cancer cells can be maintained for prolonged periods of time, and closely resemble the tumor histology. Bladder organoids can be used for drug screening, and therefore provide a platform for development of new drugs for the treatment of bladder cancer and personalized medicine.

Keywords: bladder cancer, organoid, urothelium

Abstract

Bladder cancer is a common malignancy that has a relatively poor outcome. Lack of culture models for the bladder epithelium (urothelium) hampers the development of new therapeutics. Here we present a long-term culture system of the normal mouse urothelium and an efficient culture system of human bladder cancer cells. These so-called bladder (cancer) organoids consist of 3D structures of epithelial cells that recapitulate many aspects of the urothelium. Mouse bladder organoids can be cultured efficiently and genetically manipulated with ease, which was exemplified by creating genetic knockouts in the tumor suppressors Trp53 and Stag2. Human bladder cancer organoids can be derived efficiently from both resected tumors and biopsies and cultured and passaged for prolonged periods. We used this feature of human bladder organoids to create a living biobank consisting of bladder cancer organoids derived from 53 patients. Resulting organoids were characterized histologically and functionally. Organoid lines contained both basal and luminal bladder cancer subtypes based on immunohistochemistry and gene expression analysis. Common bladder cancer mutations like TP53 and FGFR3 were found in organoids in the biobank. Finally, we performed limited drug testing on organoids in the bladder cancer biobank.

Bladder cancer is the sixth most common malignancy in men, and treatment for advanced cases has not improved in the last 30 y (1, 2). In recent years, the introduction of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) has resulted in an increase of 6% in the 10-y overall survival (3). In addition, new therapies including antibodies and immune checkpoint inhibitors have further improved the treatment and survival of bladder cancer patients (4). The success of immune checkpoint inhibitors can most likely be partially attributed to the high mutational load present in many bladder tumors (5). One reason for the lack of improvement in treatment is the absence of model systems to study the normal and malignant bladder epithelium (urothelium). The urothelium consists of several cell layers lining the bladder wall, providing an impenetrable barrier for urine (6). Under physiological conditions, renewal of the urothelium is relatively slow compared with other tissues (7). Mutations in oncogenes and tumor suppressors can lead to the formation of bladder cancer. Bladder cancer is classified in two pathological categories: non−muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) and muscle invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) (8). Patients with NMIBC have a relatively good prognosis, and can be treated by surgical removal of the tumor and subsequential intravesical chemotherapy (Mitomycin C) or immunotherapy (bacillus Calmette–Guérin) (8). In addition, NAC has been introduced and shown to be beneficial for a subset of MIBC patients (3). Currently, no good procedure exists to identify patients who will respond well or poorly to NAC. Finally, for patients with MIBC, the predominant treatment option is radical cystectomy, a procedure in which the entire bladder is removed (8). Furthermore, genetic and gene expression studies have shown that bladder cancer is a very heterogeneous disease with the presence of a large number of mutations (9, 10).

Currently, few model systems exist that faithfully recapitulate the biology of the normal urothelium and bladder cancer. Cultures of primary mouse and human bladder cells have been reported but are limited, due to their short lifespan (11, 12). Improving on this is the development of urothelial cells from induced pluripotent stem cells (13, 14). Models for the study of bladder cancer include bladder cancer cell lines. These, however, fail to recapitulate many aspects of the original tumor and are often difficult to establish (15, 16). Genetic mouse models and orthotopic xenografts for bladder cancer have been created and studied as well (17–20). These models are a faithful representation of the clinical manifestation, but are time-consuming to establish and maintain. Three-dimensional cultures of primary bladder cancer cells have recently been published (21, 22). This inspired us to apply our previously published organoid culture method of colorectal, pancreas, and prostate cancer cells on bladder cancer (23–25). Similar studies were published recently showing the feasibility of this approach (26–28). Unlike the previously published 3D culture methods, organoids can be passaged multiple times and thereby be massively expanded. To enable the growth of bladder (cancer) cells, we amended the original organoid protocol that was tailored for colorectal cancer (29). Molecular signals that regulate renewal of the urothelium under physiological conditions are incompletely understood. Upon bacterial infection, rapid proliferation of the urothelium is observed (30). For this reason, we screened several culture media conditions, in which we included growth factors and inhibitors that were previously published to influence urothelium culture (31–34). In contrast to most published media compositions for the culture of either normal mouse urothelium or human bladder cancer, our bladder (cancer) organoid media is completely defined and devoid of any animal products. Here we present the development of a culture system for the mouse urothelium. In addition, we present the construction of a living biobank with organoids derived from more than 50 bladder cancer patients.

Results

Establishment of Primary Murine Bladder Basal Cell Organoids.

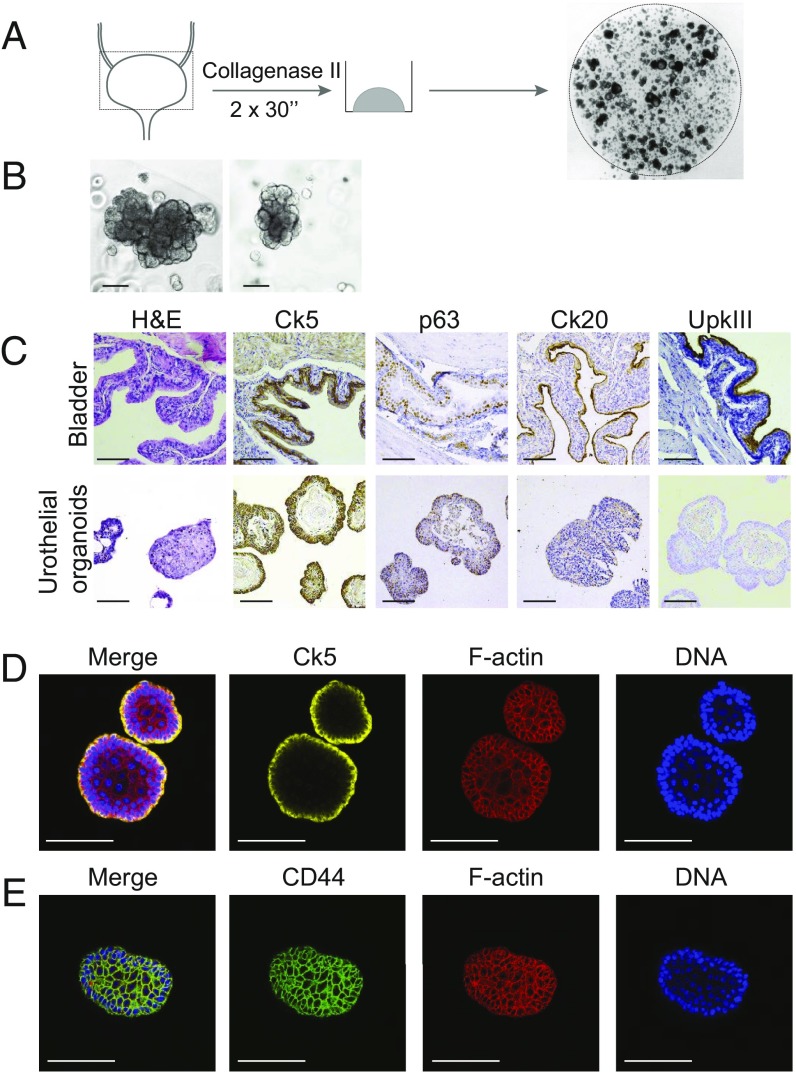

To establish murine bladder organoids, we mechanically dissociated mouse bladder tissue and extracted cells with collagenase. The resulting cell suspension was plated in basement membrane extract and supplied with culture media containing growth factors (Fig. 1A). First, we screened different culture media to find the optimal growth conditions for mouse bladder organoids (data not shown). Components of this culture media were based on previous reports on primary bladder urothelium and published organoid culture, for instance, mouse prostate (33–35). Organoids appeared in several different media conditions after only a few days in culture (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Surprisingly, epidermal growth factor was unable to sustain long-term cultures of mouse bladder organoids (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). This procedure is very efficient and allowed us to generate organoid lines in all instances that we attempted. Culture media is described in detail in the experimental procedures and is of remarkable low complexity compared with previously published organoid media. Murine bladder organoids are dense structures of cells that proliferate fast and have a grape-like morphology (Fig. 1B). When seeded at low density, murine bladder organoids grow very large in size and branch extensively (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). Although these branches seem to form a tube-like structure, imaging showed that these structures are, in fact, solid (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B). Murine bladder organoids could be passaged on a weekly basis and propagated for prolonged periods (>2 y). During this prolonged passaging (60 passages in total), no gross chromosomal abnormalities were observed, as determined by karyotyping (SI Appendix, Fig. S2C).

Fig. 1.

Establishment of murine urothelial organoid cultures. (A) Schematic of organoid culture procedure of murine bladder. (B) Representative bright-field images showing the morphology of murine bladder organoids. (Scale bars, 100 µm.) (C) IHC analysis of murine bladder (Top) and murine urothelial organoids (Bottom) for H&E, Ck5, Ck20, and UPKIII as indicated. (Scale bars, 100 µm.) (D) IF staining of murine bladder organoids with Ck5, Phalloidin (F-actin), and DAPI (DNA) as indicated. (Scale bars, 100 µm.) (E) IF staining of murine bladder organoids with CD44, Phalloidin (F-actin), and DAPI (DNA) as indicated. (Scale bars, 100 µm.)

Next, we performed immunohistochemistry (IHC) to determine the cellular composition of murine bladder organoids. Using antibodies for basal (keratin 5, Ck5), intermediate (p63), and suprabasal/umbrella (keratin 20, Ck20, and UpkIII) cell markers, we observed that most cells in the organoids resemble basal cells (Fig. 1C) (36). Remarkably, we did not observe any cells that were positive for either keratin 20 (Ck20) or uroplakin (UpkIII) proteins. These observations were corroborated by changes in gene expression measured by qPCR (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 D and E). To get a more in-depth view of the composition of our mouse bladder organoids, we performed confocal microscopy on whole-mount organoids. These experiments confirmed the presence of Ck5+ cells in the organoids (Fig. 1D). Keratin 5 is a marker of basal cells in the urothelium; therefore, we will refer to these organoids as basal bladder organoids. The presence of stem cells is a hallmark of organoids (37). Unfortunately, no urothelial stem cell markers are known, although it has been reported that urothelial stem cells reside in the basal cell layer (36). In addition, we observed that most cells in mouse bladder organoids are positive for CD44, a previously proposed marker for stem cells in bladder cancer (Fig. 1E) (38).

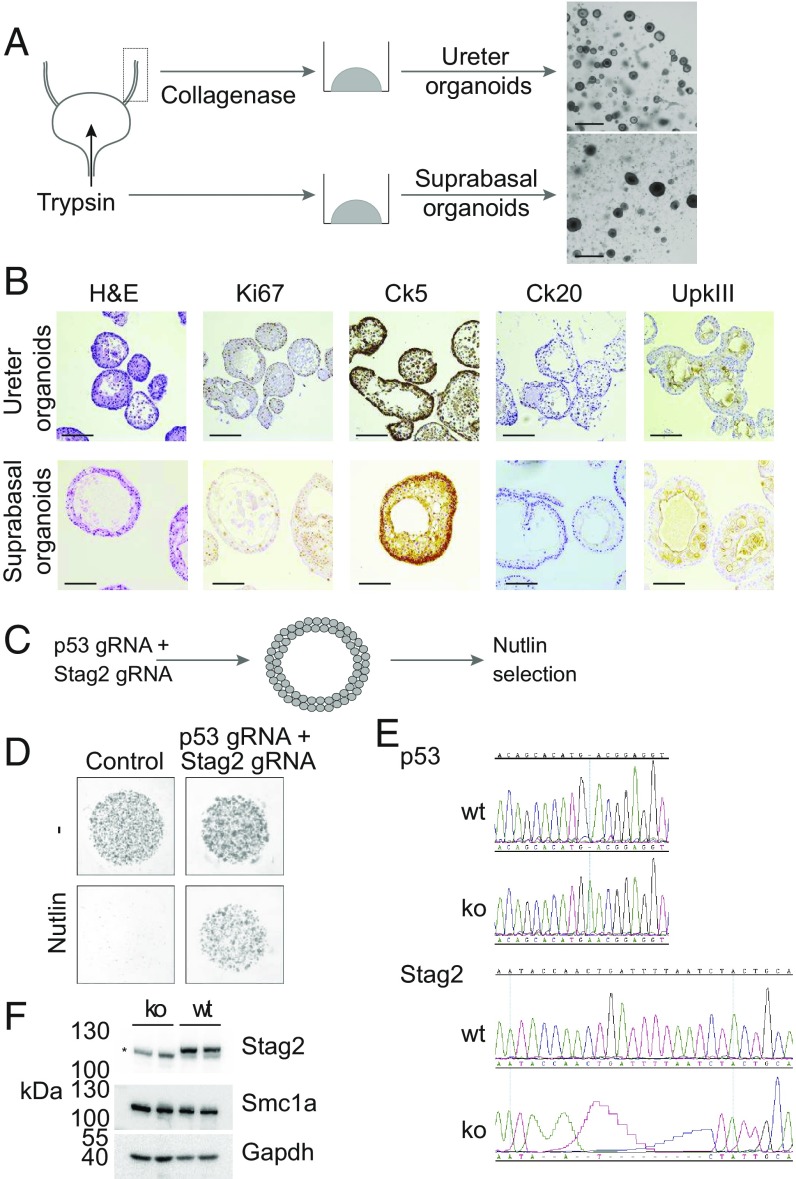

Establishment of Murine Ureter and Suprabasal Bladder Organoids.

Organoids derived from entire dissociated bladders lacked suprabasal and umbrella cells. To derive organoids containing all cell types of the urothelium, we used two alternative methods to isolate cells from the urothelium. First, we established organoid lines from ureter tissue. Mouse ureter was prepared into a cell suspension by collagenase digestion and plated into basement membrane extract, and cultured using the same media we optimized for bladder organoids. Murine ureter organoids did show a markedly different morphology compared with basal bladder organoids (Fig. 2A). Next, we extracted cells from mouse bladder by filling the bladder ex vivo with trypsin. In this way, we hoped to enrich the extracted cells for suprabasal umbrella cells that were lacking from our basal organoid cultures. Organoids derived from this procedure morphologically were very similar to ureter organoids (Fig. 2A). Both ureter and suprabasal mouse urothelial organoids could be established efficiently and passaged frequently (every 2 wk). Strikingly, when we analyzed these organoids using IHC, we observed uroplakin positive cells, indicating the presence of intermediate or umbrella cells (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, keratin 5-positive cells were also present, showing that these organoids contain both basal and suprabasal cells (Fig. 2B). Similar to basal organoids, we observed the presence of the basal marker (Ck5) predominantly on the outside of organoids (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A), while CD44 appeared to have a broader pattern of staining (SI Appendix, Fig. S3B). To get a better understanding of the transcriptional patterns in both our basal bladder and ureter organoids, we performed RNA sequencing. Approximately 1,200 genes were found to be significantly (P < 0.05) differentially expressed when comparing organoids and primary urothelium (SI Appendix, Fig. S3C). Apparent from this analysis was a very high level of expression of several basal markers (Keratins 4, 5, 6a, and 14) in basal bladder organoids (SI Appendix, Fig. S3D). Similarly, we observed an absence of luminal cell markers (Krt20 and uroplakins) in our basal organoids (SI Appendix, Fig. S3D).

Fig. 2.

Establishment of murine ureter and suprabasal bladder organoids. (A) Schematic of organoid culture procedure of murine ureter and suprabasal bladder organoids. (B) IHC analysis of murine ureter (Top) and murine suprabasal bladder organoids (Bottom) for H&E, Ki67, Ck5, Ck20, and UPKIII as indicated. (Scale bars, 100 µm.) (C) Schematic of CRISPR experiment in murine basal bladder organoids. (D) Images of transfected (p53 and Stag2 gRNAs) and control bladder organoids in absence and presence of 5 µM Nutlin in the culture media. (E) Sanger sequencing of the mouse Trp53 (Top) and Stag2 (Bottom) genomic loci. In both cases, a Sanger sequencing trace of a wild-type (wt) organoid is compared with a knockout (ko) organoid. (F) Western blot analysis of resulting organoid wt and p53/Stag2 ko clones for indicated antibodies. Asterisk (*) indicates a nonspecific background band generated by the Stag2 antibody.

Genetic Editing of Murine Basal Bladder Organoids.

Few long-term cultures of primary mouse or human urothelium have been reported (39). Bladder organoids provide a system in which genetic editing experiments can be performed. As a proof of concept, we used CRISPR/Cas9 technology to create knockout basal urothelium organoids. Basal cells (Ck5+) have been reported to be the cell of origin of MIBC and carcinoma in situ (40). We chose to genetically target one very well-established tumor suppressor (Trp53) and one recently identified tumor suppressor in urothelial carcinomas (Stag2) (41–43). Stag2 is a member of the cohesin complex that is involved in sister chromatid cohesion, DNA looping, and DNA damage repair (44). We transfected murine basal bladder organoids with Cas9 and gRNAs (guide RNAs) targeting the Trp53 and Stag2 genes. The Stag2 gene is located on chromosome X, which creates the opportunity to generate knockouts in male cells with CRISPR/Cas9 with relative ease. We performed CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing for the Tp53 and Stag2 genes in organoids derived from male and female animals. Plasmids containing Cas9 and gRNAs for Tp53 and Stag2 were transfected into bladder organoids made into single-cell suspensions. Next, we selected for cells that had inactivated their Tp53 gene by adding an MDM2 inhibitor (Nutlin) to the culture media (Fig. 2C). Organoids derived from both male and female animals were treated with TP53 gRNAs and proliferated in the presence of Nutlin (data not shown). Single organoids were picked and expanded, and the targeted genomic locus was sequenced; results shown here are from bladder organoids derived from female animals. As expected, in all clones tested, both alleles of the p53 gene were found to be mutated (Fig. 2E). We found that, in some clones (2 out of 10), in addition to a mutation in Tp53, both alleles of the Stag2 gene had incurred a mutation (Fig. 2E). We confirmed that this, indeed, resulted in a complete loss of endogenous Stag2 protein by Western blot analysis (Fig. 2F). In addition, we confirmed that the Smc1a protein, another member of the cohesin complex, is unaffected by the loss of Stag2 (Fig. 2F). Strikingly, we did not observe an obvious phenotype in our p53/Stag2 double-knockout organoids. The experiments above show that the genome of murine bladder organoids can be edited with ease and high efficiency.

Establishment of an Organoid Biobank of Human Urothelial Carcinoma.

Bladder cancer, predominantly urothelial carcinoma, is a relatively common cancer (8). Currently, very few model systems exist to study this disease. Therefore, we decided to create an in vitro organoid-based culture system of urothelial carcinoma. Patients diagnosed with MIBC are generally treated through radical cystectomy, a procedure in which the entire bladder is removed. This provides a source of tissue that we could access after obtaining informed consent from the patient. We collected samples from the bladder tumor as well as macroscopically normal urothelium from the same patient (indicated with N and T, respectively, in the organoid identifier). For urothelial carcinoma, it has been reported that normal-appearing epithelial cells can harbor genetic lesions similar to the tumor (45). These tissue pieces were prepared into a cell suspension and grown as organoids (Fig. 3A). Culture media was optimized, resulting in a growth factor mix that was very similar to the mouse bladder culture media (for details, see Experimental Procedures and SI Appendix, Fig. S4). We observed that several fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) stimulated the proliferation of human bladder cancer organoids; to understand which FGFs are essential for human bladder cancer organoids, we tested these individually (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). From this experiment, we learned that both FGF7 and FGF10 are sufficient for the growth of human bladder cancer organoids. Human urothelial organoids cultures could be established with around 50% efficiency and propagated for extended periods (>1 y). Most bladder cancer patients are diagnosed through biopsies taken using a cystoscope entering the bladder through the urethra. Pathological assessment of tissue obtained through these so-called transurethral resections (TUR) confirmed the presence of the disease and distinguishes MIBC from NMIBC. In addition, we used biopsies from TUR procedures to establish organoid cultures (Fig. 3B). After optimizing culture conditions, we set out to create a biobank of human bladder cancer organoids. This biobank was intended to capture the diversity of bladder cancer on the cellular and molecular level as previously reported (9, 10, 46). We prospectively collected samples from 53 bladder cancer patients (42 cystectomies and 11 TURs) and processed these into organoid cultures (Fig. 3C). A list of all organoid lines used in this study as well as patient information can be found in SI Appendix, Table S1. Similar to previous reports, we observed a gender bias in the samples that we collected (Fig. 3C). We initiated 133 organoid cultures from the 53 patient samples we collected. In most cystectomy cases, we started cultures from both normal and tumor tissue, and, in the case of large tumors, we established several lines of different parts of the tumor. So far, we have managed to culture several organoid lines for more than 30 passages (Fig. 3D and SI Appendix, Table S1).

Fig. 3.

Establishment of human urothelial cancer organoids. (A and B) Schematic overview and representative images of organoids derived from (A) human bladder tissue obtained from radical cystectomies and (B) biopsy material obtained from TUR procedures. (Scale bars: tissue, 1 cm; organoids, 500 µm.) (C) Overview of the composition of the human bladder cancer biobank indicating the proportion of samples obtained from each procedure (TUR and cystectomy) and the gender distribution of the bladder samples. (D) Overview of bladder cancer organoids lines; each bar represents a single organoid line.

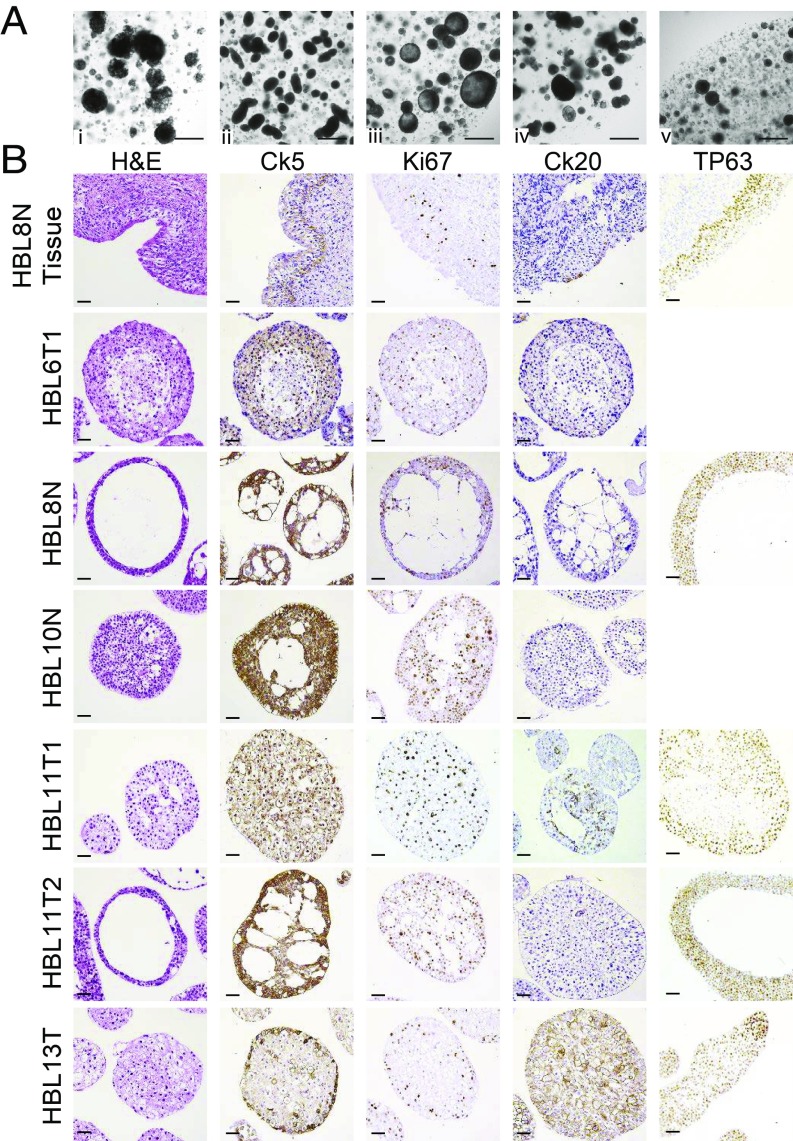

Histological Analysis of Bladder Cancer Organoids.

The vast majority of bladder cancers are classified as urothelial carcinoma (8). Within urothelial carcinoma, several different histologies are observed (47). During the culturing of the bladder cancer organoids, we observed morphological differences between samples derived from different patients (Fig. 4A). Organoids from different patients appeared as either solid (Fig. 4A, iv) or lumen-containing (Fig. 4A, iii). Some organoids appeared as smooth rounded (Fig. 4A, v) or elongated (Fig. 4A, ii) structures, while other organoids (Fig. 4A, i) had a very irregular morphology. For more in-depth analysis of our bladder organoid biobank, we performed IHC on a selection of our organoids (Fig. 4B). Haemotoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining confirmed that some organoid lines grow as solid structures (HBL11T1 and HBL13T), while others contain a lumen inside the organoid structure (HBL8N and HBL11T2). In addition, H&E staining showed several different cellular morphologies. As expected, all organoids contained active cycling cells as measured by Ki67 staining (Fig. 4B). We assessed the presence of basal (Ck5+) cells, which were present in most organoid lines (but absent in HBL6-I and HBL11T1) (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, we used TP63 to stain basal and intermediate cells, which were present in all organoids tested so far (Fig. 4B). Strikingly, we observed a big difference in the presence of CK20+ (luminal) cells in the organoids we tested so far. Some organoids (most prominent in HBL13T) were clearly positive Ck20, while most others were negative. Two commonly described subtypes of bladder cancer are the luminal and basal subtypes (46, 48). The luminal subtype is characterized by Ck20+ cells, while the basal subtype contains Ck5+ cells (46). Based on these criteria, sample HBL13T would be classified as luminal bladder cancer, while most others (HBL8N, HBL10N, and HBL11T2) resemble more the basal subtype. Worth noting is the difference between two organoid lines that were derived from the tumor in patient HBL11 (HBL11T1 and HBL11T2): Only one of the two contains Ck20+ cells. This highlights the fact that the culture of tumor samples as organoids is a great asset in the study of tumor heterogeneity.

Fig. 4.

Morphology and histology of human bladder cancer organoids. (A) Representative images of human bladder organoid lines. (Scale bar, 500 µm.) (B) IHC of normal human bladder tissue (HBL8N Tissue) and six representative human bladder cancer organoid lines. Tissue and organoids were stained for H&E, Ck5, Ki67, Ck20, and TP63 as indicated. (Scale bar, 50 µm.)

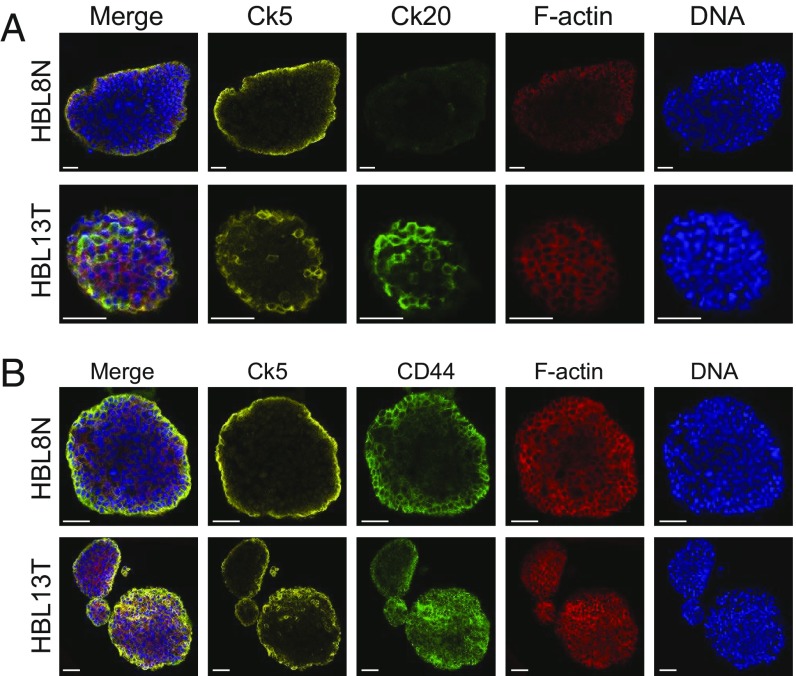

Human Bladder Cancer Organoids Contain Basal and Luminal Cells.

To confirm the presence of basal and luminal cells in human bladder cancer organoids, we performed immunofluorescent imaging. We stained organoids with different antibodies that are known to stain basal (Ck5), luminal (Ck20), and potential tumor-initiating cells (CD44) (Fig. 5) (38). We confirmed IHC results and showed that luminal and basal markers do not cooccur within cells. Indeed, we observed that heterogeneity exists between different samples; for instance, sample HBL8N contains no Ck20+ luminal cells, while HBL13T has an abundance of Ck20+ cells (Fig. 5A). We confirmed that, as expected, Ck5+ cells are never Ck20+, and vice versa (see merge image of HBL13T). In addition, we observed that both organoid lines tested here (including HBL8N, which originated from healthy urothelium) contained an abundance of CD44+ cells, a previously found marker for tumor-initiating cells in urothelial carcinoma (Fig. 5B) (49).

Fig. 5.

Cellular composition of human bladder cancer organoids. (A) IF staining of two representative human bladder cancer organoid lines with Ck5, Ck20, Phalloidin (F-actin), and DAPI (DNA) as indicated. (Scale bars, 50 µm.) (B) IF staining of two representative human bladder cancer organoid lines with Ck5, CD44, Phalloidin (F-actin), and DAPI (DNA) as indicated. (Scale bars, 50 µm.)

Functional Validation of Bladder Cancer Organoids.

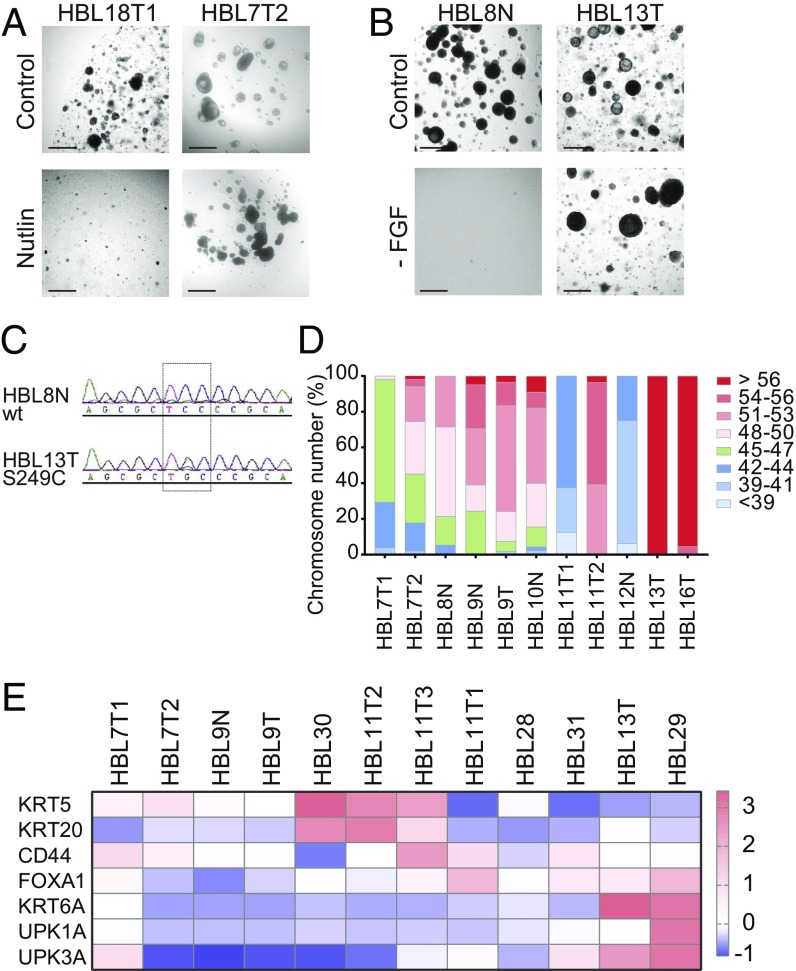

To confirm that the organoids resulted from the bladder tumors, we performed a series of functional tests. Bladder cancer is characterized by the presence of large numbers of mutations (9, 10). Several key tumor suppressors and oncogenes are among the genes that are found mutated in bladder cancer (9, 10). One of the most common tumor suppressors that is inactivated in bladder cancer is TP53 (9, 10). To identify organoid lines that harbored a mutation in TP53, we added the MDM2 inhibitor Nutlin-3 to the culture media (Fig. 6A) (50). Addition of Nutlin-3 will induce cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in cells with a functional p53 pathway but leave cells with a mutant p53 pathway unaffected. We observed that several human bladder cancer organoids showed unimpeded growth in the presence of Nutlin-3, leading to the conclusion that these organoid lines have inactivated their p53 response (Fig. 6A). Similarly, we functionally tested which human bladder organoids have an activated growth factor receptor pathway (Fig. 6B). Activation of growth factor receptor pathways in bladder cancer has been described to occur at the receptor level (activating FGFR3 mutations) as well as downstream activators (51). To screen for growth factor independence, we cultured organoids in the absence of any growth factors in the culture media. We observed that some organoid lines managed to keep proliferating in the absence of growth factors (Fig. 6B). Results from the Nutlin and FGF withdrawal experiments are summarized in SI Appendix, Fig. S6 and Table S1. Next, we performed targeted sequencing of the most frequent site of mutation in FGFR3 and confirmed that this mutation was indeed present in the growth factor-independent organoid line (Fig. 6C). Genomic instability is a common feature of bladder cancer (52). To assess gross genomic abnormalities in the bladder cancer organoids, we performed karyotyping. The majority of organoid lines tested (10 out of 11 lines) showed an abnormal number of chromosomes, leading to the conclusion that these lines are of cancerous origin (Fig. 6D). In recent years, RNA expression studies have identified several molecular subtypes of bladder cancer (53). Different studies have uncovered as many as seven subtypes or as few as two subtypes (46, 53, 54). Two commonly found subtypes of bladder cancer are the basal and luminal subtypes, which are characterized by gene expression patterns that reflect normal basal and luminal cells in the urothelium (46). We used qPCR to assess the expression levels of both basal (KRT5 and KRT6) and luminal (KRT20, UPK1A, and UPK3A) markers in human bladder cancer organoids to see whether bladder cancer organoids can be classified in basal and luminal subtypes (Fig. 6E). This analysis identified several basal (HBL30, HBL11T2, and HBL11T3) and luminal (HBL13T and HBL29) subtypes in our organoid collection (Fig. 6E). Other organoids lines (HBL7T1, HBL7T2, HBL9N, HBL9T, HBL28, and HBL31) do not clearly identify with one of the subtypes above. More in-depth analysis is required to find how these molecular subtypes are maintained in organoid lines.

Fig. 6.

Functional analysis of the human bladder cancer organoid biobank. (A) Images of human bladder cancer organoid cultures in the presence and absence of Nutlin in the culture media. (B) Images of human bladder cancer organoid cultures in presence and absence of FGF in the culture media. (C) Sanger sequencing of the FGFR3 genomic locus in human bladder cancer organoids. (D) Karyotype analysis of human bladder cancer organoids as indicated. (E) RT-qPCR for basal (KRT5 and KRT6) and luminal markers (KRT20, UPK1A and UPK3A) in human bladder cancer organoid. (Scale bars, 500 μm.)

Human Bladder Organoids as Predictors of Therapy Response.

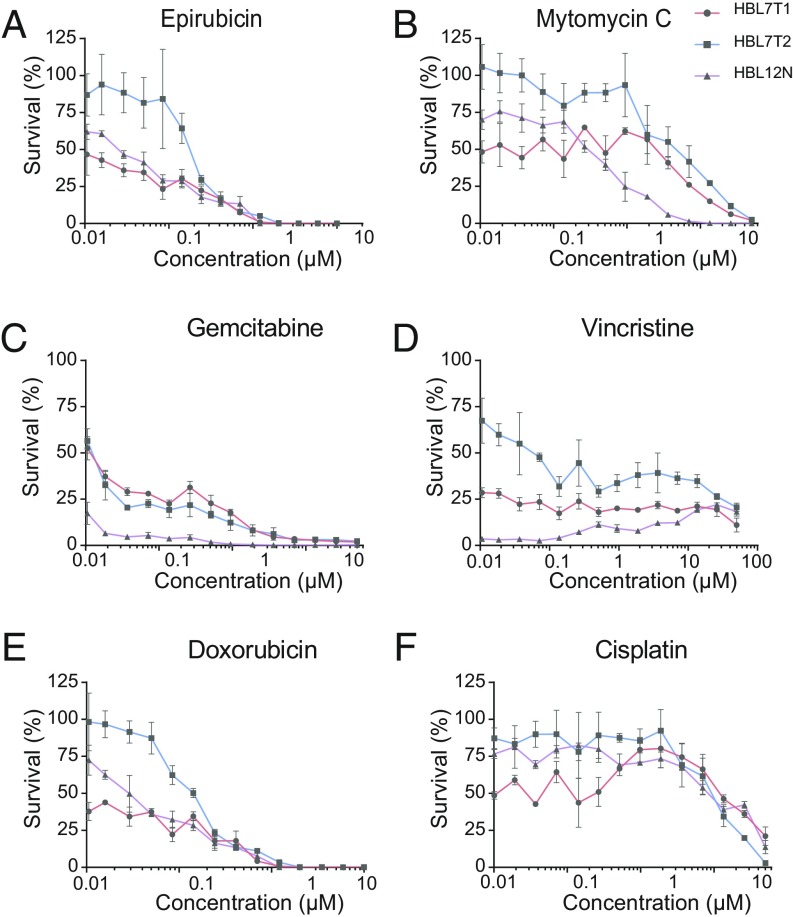

We randomly selected three organoid lines from our human bladder cancer biobank and exposed these to several commonly used chemotherapeutic agents. These drugs were chosen because they are used as first-line treatment for bladder cancer. Organoids were subjected to a range of concentrations of drugs and incubated for 5 d. We observed differences when comparing the different lines in their response to the drug treatment (Fig. 7). For example, organoid line HBL7T2 was relatively resistant to epirubicin and doxorubicin, two widely used topoisomerase inhibitors. In contrast, organoid line HBL12N was more sensitive to gemcitabine and vincristine. These experiments show how human bladder cancer organoids can be employed to determine response to anticancer drugs. Potential applications include the screening of novel drugs and predicting the response of tumors to current treatment options.

Fig. 7.

Drug response to chemotherapeutic agents. Organoids were subjected to the chemotherapy drugs (A) epirubicin, (B) mitomycin C, (C) gemcitabine, (D) vincristine, (E) doxorubicin, and (F) cisplatin. Cell viability was measured and plotted as percentage of untreated organoids.

Discussion

Preclinical bladder cancer research has mostly been performed on a small set of bladder cancer cell lines (15). These cell lines poorly recapitulate many features seen in human bladder tumors. In addition, mouse models for bladder cancer (PDX and genetic models) have been generated (20). Here, we have developed a culture method for human bladder cancer cells and mouse primary urothelial cells. This culture method is based on the previously established organoid cultures for human and mouse normal and tumor cells (23, 55). Recently, the generation of mouse bladder organoids was reported by several research groups (26, 27, 56). In contrast to previously published culture methods of normal mouse urothelium, organoid cultures of normal mouse urothelium could be passaged for prolonged periods of time. In addition, mouse urothelial organoids can be genetically manipulated with relative ease, as shown here for the Trp53 and Stag2 genes. These experiments show that mouse bladder organoids provide an effective tool to model and study oncogenic mutations.

Compared with traditional cell line generation, human bladder cancer organoids can be generated at high efficiency (60 to 70%). Due to this high efficiency, we have been able to generate several independent organoid lines from individual tumors, which creates the potential to study intratumor heterogeneity in great detail. In addition, we grew organoids from macroscopically healthy urothelium from patients whose bladders were removed in cystectomy procedures. Upon analysis, we found that several tissues that were pathologically scored healthy were in fact premalignant (based on p53 status and karyotype). This confirms earlier findings that describe the field effect in bladder cancer: Premalignant cells spread through the epithelium and, upon acquiring more mutations, give rise to the formation of bladder cancer (49).

Organoids are classified as stem cell-containing self-organizing structures that can be propagated for prolonged periods of time (37). The exact identity of the urothelial stem cell is currently a matter of debate (30, 57, 58). We found that all mouse and most of our human bladder (cancer) organoids contained cells that stained positive for keratin 5 and CD44, two putative (cancer) stem cell markers (30, 38). Further analysis of our organoids can potentially shed light on the actual stem cell in the urothelium.

Bladder cancer is a very heterogeneous disease on the molecular and genetic level (9). Histological and immunofluorescence (IF) analysis of our human bladder cancer organoids showed a large variation between organoids from different tumors. In addition, we confirmed that human bladder organoids can also be classified based on their gene expression signature, similar to what has been shown for tumor samples (59). The fact that bladder organoids can be grown for prolonged periods allowed us to perform functional studies. For instance, we show that cells with a very common FGFR3 mutation (S249C) can proliferate for prolonged periods in the absence of any growth factor in the media. This also opens the possibility to screen (novel) drugs on bladder cancer organoids, potentially yielding much-needed new therapeutics for the treatment of this disease. On exiting area is the application of immunotherapy for the treatment of bladder cancer. Several groups have reported the coculture of immune cells with organoids; these models could be very useful for bladder cancer to identify patients who will respond well to immunotherapy regimen.

Experimental Procedures

Human Tissue.

Human bladder tissue was obtained from the University Medical Center Utrecht (UMCU). Ethical approval was granted by the Medical Ethical Committee of the UMCU. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients involved. Bladder tissue was obtained through TUR or cystectomy procedures. All tissue samples were examined by a dedicated uropathologist.

Mouse Bladder Organoid Culture.

To collect cells for murine basal bladder and ureter organoids, after surgical excision of the murine bladder or ureter, the tissue was cut into small pieces (1 mm to 2 mm) with a surgical blade. Next, the tissue was placed into a collagenase solution (1 mg/mL of collagenase from Clostridium histolyticum, C9891; Sigma Aldrich) in Adv DMEM/F-12 (ThermoFisher 12634028) with ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632, 10 µM). The tissue was incubated at 37 °C for 2 × 30 min while shaking. Resulting cell suspension was filtered through a 70-µm filter, and cells were collected through centrifugation. To collect cells for murine suprabasal organoids, murine bladders were surgically removed. Bladders were filled with between 0.5 mL and –1 mL of TrypLE (ThermoFisher 12605036) containing ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632, 10 µM) using a hypodermic needle. The bladder opening was closed using a suture to prevent leakage. Filled bladders were placed in a Petri dish with Adv DMEM/F-12 and placed in a humidified incubator at 37 °C for 30 min. After incubation, cell suspension was filtered through a 70-µm filter, and cells were collected through centrifugation. Next (similar for basal, ureter, and suprabasal organoids), cells were plated in ∼200 µL of Basement Membrane Extract (BME, Cultrex 3533-001-02) in four individual wells of a prewarmed 24-well plate. After the BME was solidified, mouse bladder media [Adv DMEM/F-12, FGF10 (100 ng/mL of Peprotech 100-26), FGF7 (25 ng/mL of Peprotech 100-19), A83-01 (500 nM), and B27 (2% ThermoFisher 17504001)] was added. Mouse ureter, basal, and suprabasal bladder organoids were passaged weekly and either sheared through a glass pipet or by dissociation using TrypLE. ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632, 10 µM) was added to the media after passaging, to prevent cell death. Organoids were frozen in freezing media (50% FBS, 10% DMSO, and 40% Adv DMEM/F-12) and could be recovered efficiently.

Human Bladder Organoids.

Human bladder tissue was examined by a trained pathologist. In the cystectomy cases, whenever possible, we obtained a piece of tumor tissue and a piece of normal- appearing tissue from the same patient. The tissue was cut into smaller pieces (1 mm to –2 mm) with a surgical blade and digested with collagenase (1 mg/mL of collagenase from Clostridium histolyticum, C9891; Sigma Aldrich) in Adv DMEM/F-12 (ThermoFisher 12634028) with ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632, 10 µM) for 30 min′ at 37 °C. The incubation was repeated once, after which the cell suspension was filtered through a 70-µm strainer. Cells were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in ∼200 µL of BME (Cultrex 3533-001-02) and plated into four individual wells of a prewarmed 24-well plate. When the BME was solidified, human bladder organoid media was added [Adv DMEM/F-12, FGF10 (100 ng/mL of Peprotech 100-26), FGF7 (25 ng/mL of Peprotech 100-19), FGF2 (12.5 ng/mL of Peprotech 100-18B), B27 (2% ThermoFisher 17504001), A83-01 (5 µM), N-acetylcysteine (1.25 mM), and nicotinamide (10 mM)]. Human bladder organoids were passaged biweekly and either sheared through a glass pipet or by dissociation using TrypLE (ThermoFisher 12605036). ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632, 10 µM) was added to the media after passaging, to prevent cell death. Organoids were frozen in freezing media (50% FBS, 10% DMSO, and 40% Adv DMEM/F-12) and could be recovered efficiently.

Histology.

Organoids and tissue were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 h to 6 h, dehydrated, and paraffin-embedded according to standard histology procedures. Sections were stained with H&E and the following antibodies: Keratin 5 (AF138 COVANCE 160P-100), Ki67 (Monosan MONX10283), Keratin 20 (KS20.8 Dako M7019), TP63 (4A4 Abcam ab735), and Uroplakin III (AU1 Progen 651108) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Images were acquired with a Leica DM4000 microscope.

Immunofluorescence.

Organoids were fixed in 4% formaldehyde solution for 6 h and overnight (o/n). Next, fixed organoids were blocked with 2% donkey serum in PBS. Blocked organoids were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton in PBS. Primary antibody was incubated in 0.1% Triton in PBS at 4 °C o/n. Antibodies used in this study are Keratin 5 (AF138 COVANCE 160P-100), Keratin 20 (KS20.8 Dako M7019), and CD44 (IM7 Biolegend 103015). After incubation with the primary antibody, organoids were washed, F-actin was stained with Phalloidin (Sigma 65906), and DNA was stained with DAPI.

Transfection.

Mouse bladder organoids were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (ThermoFisher 11668027). Mouse bladder organoids were dissociated to single cells with TrypLE (brand) and passed through a 70-µm cell strainer. Cells were resuspended in regular culture media, added to the Lipofectamine/DNA mixture, and plated in a suspension cell culture plate. Cells were centrifuged at 600 × g for 60 min at 32 °C and subsequently placed back into the tissue culture incubator for 4 h to 6 h. Next, cells were plated in BME in regular culture media.

CRISPR Genome Editing.

CRISPR experiments in mouse bladder organoids were performed using two different methods. For TP53, we used a separate gRNA and Cas9 plasmid as described previously (60). To target mouse Stag2, we used the pSpCas9(BB)-2A-Puro or pSpCas9(BB)-2A-GFP plasmid (61). Here we cotransfected plasmids encoding the TP53 gRNA together with pSpCas9(BB)-2A-Puro with a Stag2 gRNA. The gRNA sequences used in this study are mouse TP53: AAGTCACAGCACATGACGG and mouse Stag2: ACTGATTTTAATCTACTGCA. Nutlin-3 (5 µM) was added 72 h after transfection, and organoids were maintained in Nutlin-containing culture media until viable clonal organoids were observed. Single organoids were picked and expanded. Genomic DNA was isolated and amplified to confirm the presence of mutations at the gRNA target site. PCR primers used were TP53 (F: TGGTGCTTGGACAATGTGTT, R: TACCTTATGAGCCACCCGAG) and Stag2 (F: CTCAGGTTACTGTGTCTTGAGAA, R: TGCCACTTCTGTAATATTTTGGATC). PCR products were sequenced using one of the primers used for amplification to identify mutations introduced.

Western Blot.

Organoids were recovered from BME and incubated in TrypLE for 5 min to remove remaining BME. Organoids were resuspended in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer and sonicated to ensure efficient lysis. Protein lysates were loaded on SDS/PAGE and transferred to immobilon membrane. Proteins were visualized using the following antibodies: Stag2: J-12 Santacruz, SMC1A: Bethyl A300-055A, and GAPDH: Abcam ab9485.

Karyotyping.

Organoids were split 2 d to 5 d before the start of karyotype procedure. Cells were treated with colcemid (final concentration: 100 ng/mL; ThermoFisher 15210040) in the culture media for 16 h. Cells were collected and made into single-cell suspension by TrypLE addition. Single cells were swollen by addition of 75 mM KCl and incubation at 37 °C for 10 min. Cells were fixed by addition of MeOH/HAc (3:1) while vortexing the cell suspension. Fixed cells were dropped on a microscopy slide and stained with DAPI. Metaphases were imaged with a 100× objective.

The qRT-PCR.

RNA was isolated using an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen 74104). The cDNA was prepared using GoScript reverse transcriptase (Promega A5003) using random hexamers (ref). The qRT-PCR was run using Biorad SYBR green supermix (1708886). Primers used were mHprt: F-CAGTACAGCCCCAAAATGGT, R-CAAGGGCATATCCAACAACA; mKrt5: F-GTCAGGACTGAGGAGAGGGA, R-TGTCCAGGACCTTGTTCTGC; mTrp63: F-CCTCCAACACAGATTACCCG, R-AGCTTCTTCAGTTCGGTGGA; mKrt20: F-CGAGCACCATCCGAGACTAT, R-TGCAGCCAGCTTAGCATTGT; mUpk1B: F-GAAGAAGGCAGAGGAGACCA, R-AATCAACAGGCCCTGGAAG; mUpk2: F-GTATGGCATCCACACTGCCT, R-GAGACAGCAGACCAGAGAGG; mUpk3a: F-AGCGGCTCTTACGAGGTTTA, R-AGTAGTGCTCAGTGGGACGC; hKRT5: F-GGAGCTCATGAACACCAAGC,

R-CTGGTCCAACTCCTTCTCCA; hKRT6A: F-CTGAGATCGACCACGTCAAG, R-CAGCTTGTTCTTGGCATCCT; hKRT20: F-TTGAAGAGCTGCGAAGTCAG, R-GAAGTCCTCAGCAGCCAGTT; CD44: F-GACAAGTTTTGGTGGCACG,

R-CACGTGGAATACACCTGCAA; hFOXA1: F-CTGTGAAGATGGAAGGGCAT,

R-GCCTGAGTTCATGTTGCTGA; hUPK1A: F-ATCACGGTGGGTGTAGGACG,

R-TGCCATCTTCTGCGGCTTCT; and hUPK3A: F-CAATATGTCCACGGGCTTG,

R-CGTGTCGATCGTCGAGTATG.

RNA Sequencing.

Urothelium was isolated by scraping the surface of an opened murine bladder with a surgical blade. RNA of organoids and urothelium was isolated using an RNeasy kit. RNA sequencing of mouse urothelium and organoids was performed using the CEL-Seq2 protocol (62). Paired-end reads from Illumina sequencing were aligned to the human transcriptome with BWA (63). Differential expressed genes were identified using the Bioconductor package DESeq (28).

Drug Response.

Organoids were split using TrypLE and strained through a 70-µm filter and replated in BME. Two days later, organoids were counted, and 1,000 organoids per well were plated in a 384-well plate in culture media containing 5% BME. Drugs were added at the indicated concentration, and cells were incubated for 5 d. Cell viability was measured using CellTiter-Glo 3D (Promega G9681).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Marie Bannier for critical reading of the manuscript; members of the Clevers group for useful discussion; and Willem de Blok (Master in Advanced Nursing Practice) for patient counseling. This work is part of the Oncode Institute, which is partly financed by the Dutch Cancer Society and was funded by Dutch Cancer Society Grant KWF-BUIT2012-5358.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1803595116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Dutch Cancer Registry (NKR) 2018 Available at https://www.cijfersoverkanker.nl/. Accessed February 1, 2018.

- 2.Berdik C. Unlocking bladder cancer. Nature. 2017;551:S34–S35. doi: 10.1038/551S34a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hermans TJN, et al. Neoadjuvant treatment for muscle-invasive bladder cancer: The past, the present, and the future. Urol Oncol. 2018;36:413–422. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2017.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Felsenstein KM, Theodorescu D. Precision medicine for urothelial bladder cancer: Update on tumour genomics and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Urol. 2018;15:92–111. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2017.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gopalakrishnan D, Koshkin VS, Ornstein MC, Papatsoris A, Grivas P. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in urothelial cancer: Recent updates and future outlook. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2018;14:1019–1040. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S158753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khandelwal P, Abraham SN, Apodaca G. Cell biology and physiology of the uroepithelium. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;297:F1477–F1501. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00327.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jost SP. Cell cycle of normal bladder urothelium in developing and adult mice. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol Incl Mol Pathol. 1989;57:27–36. doi: 10.1007/BF02899062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanli O, et al. Bladder cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17022. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robertson AG, et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Cell. 2017;171:540–556.e25. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network Comprehensive molecular characterization of urothelial bladder carcinoma. Nature. 2014;507:315–322. doi: 10.1038/nature12965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daher A, et al. Growth, differentiation and senescence of normal human urothelium in an organ-like culture. Eur Urol. 2004;45:799–805. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Southgate J, Hutton KA, Thomas DF, Trejdosiewicz LK. Normal human urothelial cells in vitro: Proliferation and induction of stratification. Lab Invest. 1994;71:583–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anumanthan G, et al. Directed differentiation of bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells into bladder urothelium. J Urol. 2008;180(Suppl 4):1778–1783. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.04.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Osborn SL, et al. Induction of human embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells into urothelium. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2014;3:610–619. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2013-0131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Earl J, et al. The UBC-40 urothelial bladder cancer cell line index: A genomic resource for functional studies. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:403. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1450-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nickerson ML, et al. Molecular analysis of urothelial cancer cell lines for modeling tumor biology and drug response. Oncogene. 2017;36:35–46. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahmad I, Sansom OJ, Leung HY. Exploring molecular genetics of bladder cancer: Lessons learned from mouse models. Dis Model Mech. 2012;5:323–332. doi: 10.1242/dmm.008888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu XR. Biology of urothelial tumorigenesis: Insights from genetically engineered mice. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2009;28:281–290. doi: 10.1007/s10555-009-9189-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inoue T, Terada N, Kobayashi T, Ogawa O. Patient-derived xenografts as in vivo models for research in urological malignancies. Nat Rev Urol. 2017;14:267–283. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2017.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kobayashi T, Owczarek TB, McKiernan JM, Abate-Shen C. Modelling bladder cancer in mice: Opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15:42–54. doi: 10.1038/nrc3858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoshida T, et al. High-dose chemotherapeutics of intravesical chemotherapy rapidly induce mitochondrial dysfunction in bladder cancer-derived spheroids. Cancer Sci. 2015;106:69–77. doi: 10.1111/cas.12567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burgués JP, et al. A chemosensitivity test for superficial bladder cancer based on three-dimensional culture of tumour spheroids. Eur Urol. 2007;51:962–969, and discussion (2007) 51:969–970. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van de Wetering M, et al. Prospective derivation of a living organoid biobank of colorectal cancer patients. Cell. 2015;161:933–945. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karthaus WR, et al. Identification of multipotent luminal progenitor cells in human prostate organoid cultures. Cell. 2014;159:163–175. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huch M, et al. Unlimited in vitro expansion of adult bi-potent pancreas progenitors through the Lgr5/R-spondin axis. EMBO J. 2013;32:2708–2721. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee SH, et al. Tumor evolution and drug response in patient-derived organoid models of bladder cancer. Cell. 2018;173:515–528.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Real FX, et al. 2018. Urothelial organoids originate from Cd49f-high stem cells and display notch-dependent differentiation capacity. bioRxiv: 287979. Preprint, posted March 23, 2018.

- 28.Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sato T, et al. Long-term expansion of epithelial organoids from human colon, adenoma, adenocarcinoma, and Barrett’s epithelium. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1762–1772. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shin K, et al. Hedgehog/Wnt feedback supports regenerative proliferation of epithelial stem cells in bladder. Nature. 2011;472:110–114. doi: 10.1038/nature09851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okuyama H, et al. Involvement of heregulin/HER3 in the primary culture of human urothelial cancer. J Urol. 2013;190:302–310. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.12.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Daher A, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor regulates normal urothelial regeneration. Lab Invest. 2003;83:1333–1341. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000086380.23263.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bagai S, et al. Fibroblast growth factor-10 is a mitogen for urothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:23828–23837. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201658200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tash JA, David SG, Vaughan ED ED, Herzlinger DA. Fibroblast growth factor-7 regulates stratification of the bladder urothelium. J Urol. 2001;166:2536–2541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Drost J, et al. Organoid culture systems for prostate epithelial and cancer tissue. Nat Protoc. 2016;11:347–358. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2016.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ho PL, Kurtova A, Chan KS. Normal and neoplastic urothelial stem cells: Getting to the root of the problem. Nat Rev Urol. 2012;9:583–594. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2012.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Drost J, Clevers H. Translational applications of adult stem cell-derived organoids. Development. 2017;144:968–975. doi: 10.1242/dev.140566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chan KS, et al. Identification, molecular characterization, clinical prognosis, and therapeutic targeting of human bladder tumor-initiating cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:14016–14021. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906549106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Boer WI, et al. Functions of fibroblast and transforming growth factors in primary organoid-like cultures of normal human urothelium. Lab Invest. 1996;75:147–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van Batavia J, et al. Bladder cancers arise from distinct urothelial sub-populations. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:982–991. doi: 10.1038/ncb3038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Balbás-Martínez C, et al. Recurrent inactivation of STAG2 in bladder cancer is not associated with aneuploidy. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1464–1469. doi: 10.1038/ng.2799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guo G, et al. Whole-genome and whole-exome sequencing of bladder cancer identifies frequent alterations in genes involved in sister chromatid cohesion and segregation. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1459–1463. doi: 10.1038/ng.2798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Solomon DA, et al. Frequent truncating mutations of STAG2 in bladder cancer. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1428–1430. doi: 10.1038/ng.2800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nasmyth K, Haering CH. Cohesin: Its roles and mechanisms. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:525–558. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Czerniak B, et al. Genetic modeling of human urinary bladder carcinogenesis. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2000;27:392–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Choi W, et al. Identification of distinct basal and luminal subtypes of muscle-invasive bladder cancer with different sensitivities to frontline chemotherapy. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:152–165. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Amin MB. Histological variants of urothelial carcinoma: Diagnostic, therapeutic and prognostic implications. Mod Pathol. 2009;22(Suppl 2):S96–S118. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2009.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aine M, Eriksson P, Liedberg F, Sjödahl G, Höglund M. Biological determinants of bladder cancer gene expression subtypes. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10957. doi: 10.1038/srep10957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thomsen MBH, et al. Comprehensive multiregional analysis of molecular heterogeneity in bladder cancer. Sci Rep. 2017;7:11702. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11291-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vassilev LT, et al. In vivo activation of the p53 pathway by small-molecule antagonists of MDM2. Science. 2004;303:844–848. doi: 10.1126/science.1092472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Iyer G, Milowsky MI. Fibroblast growth factor receptor-3 in urothelial tumorigenesis. Urol Oncol. 2013;31:303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fadl-Elmula I, et al. Karyotypic characterization of urinary bladder transitional cell carcinomas. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2000;29:256–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McConkey DJ, Choi W, Dinney CP. Genetic subtypes of invasive bladder cancer. Curr Opin Urol. 2015;25:449–458. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0000000000000200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sjodahl G, et al. A molecular taxonomy for urothelial carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:3377–3386. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0077-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sachs N, et al. A living biobank of breast cancer organoids captures disease heterogeneity. Cell. 2018;172:373–386.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Halstead AM, et al. Bladder-cancer-associated mutations in RXRA activate peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors to drive urothelial proliferation. eLife. 2017;6:e30862. doi: 10.7554/eLife.30862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Colopy SA, Bjorling DE, Mulligan WA, Bushman W. A population of progenitor cells in the basal and intermediate layers of the murine bladder urothelium contributes to urothelial development and regeneration. Dev Dyn. 2014;243:988–998. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.24143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gandhi D, et al. Retinoid signaling in progenitors controls specification and regeneration of the urothelium. Dev Cell. 2013;26:469–482. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Choi W, et al. Intrinsic basal and luminal subtypes of muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Nat Rev Urol. 2014;11:400–410. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2014.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Drost J, et al. Sequential cancer mutations in cultured human intestinal stem cells. Nature. 2015;521:43–47. doi: 10.1038/nature14415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ran FA, et al. Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:2281–2308. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hashimshony T, et al. CEL-seq2: Sensitive highly-multiplexed single-cell RNA-seq. Genome Biol. 2016;17:77. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-0938-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.