Abstract

Study Objectives:

Upper airway collapsibility is a key determinant of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) which can influence the efficacy of certain non-continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) treatments for OSA. However, there is no simple way to measure this variable clinically. The present study aimed to develop a clinically implementable tool to evaluate the collapsibility of a patient’s upper airway.

Methods:

Collapsibility, as characterized by the passive pharyngeal critical closing pressure (Pcrit), was measured in 46 patients with OSA. Associations were investigated between Pcrit and data extracted from patient history and routine polysomnography, including CPAP titration.

Results:

Therapeutic CPAP level, demonstrated the strongest relationship to Pcrit (r2=0.51, p < .001) of all the variables investigated including apnea-hypopnea index, body mass index, sex, and age. Patients with a mildly collapsible upper airway (Pcrit ≤ −2 cmH2O) had a lower therapeutic CPAP level (6.2 ± 0.6 vs. 10.3 ± 0.4 cmH2O, p < .001) compared to patients with more severe collapsibility (Pcrit > −2 cmH2O). A therapeutic CPAP level ≤8.0 cmH2O was sensitive (89%) and specific (84%) for detecting a mildly collapsible upper airway. When applied to the independent validation data set (n = 74), this threshold maintained high specificity (91%) but reduced sensitivity (75%).

Conclusions:

Our data demonstrate that a patient’s therapeutic CPAP requirement shares a strong predictive relationship with their Pcrit and may be used to accurately differentiate OSA patients with mild airway collapsibility from those with moderate-to-severe collapsibility. Although this relationship needs to be confirmed prospectively, our findings may provide clinicians with better understanding of an individual patient’s OSA phenotype, which ultimately could assist in determining which patients are most likely to respond to non-CPAP therapies.

Keywords: Obstructive sleep apnea, CPAP, phenotyping, collapsibility, Pcrit

Statement of Significance

Upper airway collapsibility is the most important physiological trait involved in the pathogenesis of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). The severity of an individual’s collapsibility has been shown to influence the efficacy of a number of therapies for OSA; however, current methods for measuring upper airway collapsibility are not practical for use in a clinical setting. This study demonstrates that a patient’s therapeutic continuous positive airway pressure level requirement, a measurement easily and routinely determined in many sleep clinics, provides useful, predictive, information regarding a patient’s upper airway collapsibility. Such information may ultimately help clinicians tailor existing as well as novel treatments toward an individual’s underlying abnormalities.

INTRODUCTION

Although it is well recognized that patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) have a more collapsible upper airway compared to healthy controls,1 recent evidence has highlighted a number of nonanatomical factors that also contribute to airway collapse. These include a hypersensitive ventilatory control system,2 an ineffective upper airway dilator muscle response,3 and a low respiratory arousal threshold.4 These traits vary substantially between patients, such that OSA can manifest from a number of different physiological mechanisms. Such variability in the OSA phenotype may therefore explain the variable efficacy of the current non-CPAP therapies for treating OSA. Importantly, emerging evidence demonstrates that people with OSA with less severe upper airway collapsibility are more likely to respond to therapies targeting both anatomical (ie, oral appliances5 and weight loss6) and nonanatomical causes of OSA (ie, oxygen/sedatives7). It should be noted, however, that this has not been found to be the case for all CPAP-alternative treatments.8,9

One of the major hurdles to adopting a personalized approach to treating OSA is the lack of clinically implementable physiological screening tools. Currently, methods for quantifying the degree of upper airway collapsibility require specialized equipment and technically difficult methodologies. As such, there is a need to establish simplified ways of determining this pathophysiological information to allow personalized treatment approaches to be implemented in the clinic. Therefore, the current study aimed to develop a method of determining upper airway collapsibility using routinely collected clinical information from a patient’s history or from clinical polysomnography (PSG) or CPAP titration.

METHODS

Participants

We analyzed data from 60 people with OSA who participated in studies conducted in sleep laboratories at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Monash University. Participants were recruited through the general community and at sleep clinics at either site. All patients were screened and excluded if they had a history of renal failure, neuromuscular disease, neurological disorders, central sleep apnea, uncontrolled diabetes, heart failure, thyroid disease, or any other uncontrolled medical condition. Patients were also excluded if they were taking any medications known to affect sleep, ventilation, or muscle control. Forty-two (70%) of these patients had been regularly receiving treatment (either via CPAP or an oral appliance) before study enrolment but were not required to abstain from treatment before study procedures. Written informed consent was provided before enrolment, which was approved by the local ethics committees.

Experimental Protocol

At each of the sites, participants underwent an in-laboratory clinical PSG to confirm the presence and severity of OSA (defined by apnea-hypopnea index [AHI] >10 events/hour) and a research PSG to measure the OSA traits (including upper airway collapsibility). For the clinical PSG, a standard clinical montage recorded electroencephalogram (EEG), electrooculogram, chin and leg electromyogram, electrocardiogram, nasal pressure, nasal/oral thermistor, thoracic and abdominal respiratory effort, and arterial oxygen saturation. Sleep staging, arousals, and respiratory events were scored according to standard criteria.10 During the research PSG, in addition to the standard clinical montage, patients slept with a nasal mask which facilitated the measurement of airflow via a pneumotachometer (Hans Rudolph, Kansas City, Missouri), mask pressure (Validyne, Northridge, CA), and CO2 (Vacumed, Ventura, California). CPAP was delivered by a device capable of delivering both positive and negative pressure (+20 cmH2O to −20 cmH2O) as well as near instantaneously switching between two pressure levels (Philips-Respironics, Murrysville, Pennsylvania).

Determining Therapeutic CPAP Level

During supine non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, CPAP level was titrated to a level sufficient to eliminate apnea, hypopnea, snoring, and inspiratory flow limitation (ie, therapeutic CPAP level). The step size (in cmH2O) and the time interval between individual increases in CPAP level was left to the discretion of the titrating researcher but was no greater than 1 cmH2O per minute of sleep. The therapeutic CPAP level was reassessed multiple times during the research PSG by reducing CPAP to a confirmed subtherapeutic pressure and retitrating until respiratory events and flow limitation were again resolved.

Measuring Upper Airway Collapsibility

Passive upper airway critical closing pressure (Pcrit) was measured during the research PSG to assess upper airway collapsibility using standard techniques.11 Briefly, stepwise reductions in the CPAP from the therapeutic level for five breaths were performed until apnea was produced during stable supine NREM sleep. Linear regressions were performed between the peak inspiratory airflow and mask pressure for breaths three to five (if the breaths were flow limited) after each CPAP drop. The x intercept of the peak inspiratory airflow versus mask pressure regression (zero flow crossing) was taken as the Pcrit. Multiple series of these stepwise CPAP reductions were conducted throughout the sleep period, each yielding a measurement of the participant’s Pcrit. Each individual’s Pcrit measurements were then averaged to provide a single Pcrit value for each participant.

Data and Statistical Analysis

A “development” data set (n = 60) consisting of physiological (Pcrit), clinical (AHI, therapeutic CPAP), and anthropometric (age, sex, body mass index [BMI]) data was examined for variables capable of accurately predicting upper airway collapsibility. In the studies in which a treatment intervention was tested, only data from the baseline/placebo conditions were used. Using univariate regression, the development data set was examined for associations between Pcrit and the anthropometric/clinical variables described above to determine the best predictors. To control for colinear interactions, a multivariate linear regression was then performed incorporating all independent variables to determine which predictors remained significant. Hierarchical multiple regression was performed to determine whether a multivariate model provided a better prediction than any of the single predictors. A binary classification was used to differentiate patients with a mildly collapsible airway (defined by Pcrit ≤ −2 cmH2O) from a moderate-severely collapsible airway (defined as a Pcrit > −2 cmH2O) based on previously published data.12 Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were then calculated to determine the best threshold values (based on sensitivity and specificity) that differentiated patients' groups based on these collapsibility categories.

Those variables determined in the development data were then tested by assessing their accuracy against an independent (“validation”) data set (n = 75) collected as part of a previously published physiological study with a similar number of patients.12 Sensitivity, specificity, positive, and negative predictive values were compared between the development and validation data set.

RESULTS

Of the 60 participants included in the development analysis, successful Pcrit measurements were obtained in 46 patients (77%). The validation data set included 75 participants, 74 (99%) of whom had successful Pcrit measurements.12 Demographic and anthropometric information for both groups is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Development and Validation Data Sets.

| Characteristics | Development data set (n = 46) | Validation data set (n = 74) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 30 males:16 females | 49 males:25 females | .91 |

| Age (years) | 50.8 ± 12.0 | 44.7 ± 11.6 | <.01 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 33.8 ± 7.9 | 33.0 ± 6.7 | .55 |

| AHI (events/hour) | 40.8 [43.4] | 29.3 [45.4] | .01 |

| Therapeutic CPAP (cmH2O) | 9.5 ± 3.0 | 9.4 ± 3.5 | .92 |

| Pcrit (cmH2O) | 0.2 ± 3.3 | −1.5 ± 4.9 | .04 |

AHI = apnea-hypopnea indexl; BMI = body mass index; CPAP = continuous positive airway pressure.

Mean ± standard deviation, or median [interquartile range] are shown.

Associations Between Pcrit and Demographic and Polysomnographic Indexes

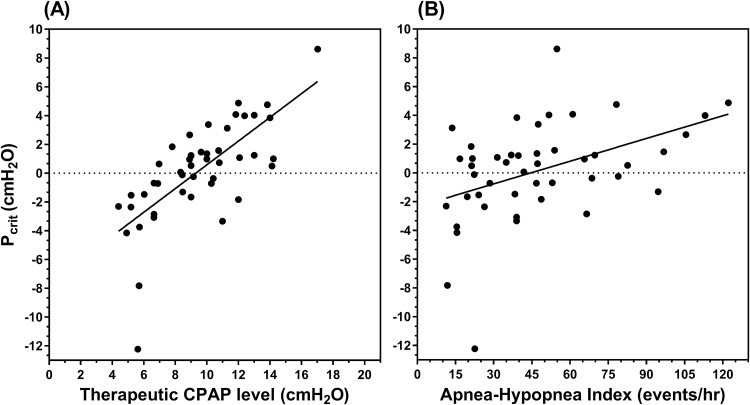

In the development data set, no significant associations were found between Pcrit and BMI, age, or male sex, see Figure 1. A significant association was found between Pcrit and AHI (r2 = 0.19, p = .002). Of each of the variables investigated, therapeutic CPAP level demonstrated the strongest relationship to Pcrit (r2 = 0.51, p < .001), see Figure 2.

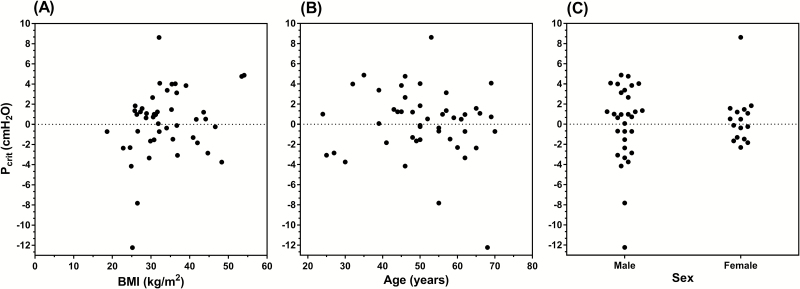

Figure 1.

Univariate associations between Pcrit and body mass index (BMI), age, and sex. Neither (A) BMI (r2 = 0.07, p = .07), (B) age (r2 = 0.01, p = .44), nor (C) sex (r2 = 0.004, p = .66) were found to be significantly associated with Pcrit. Data from the development data set are shown..

Figure 2.

Clinical predictors of Pcrit. Univariate linear regressions demonstrated (A) therapeutic CPAP level to be the strongest predictor of Pcrit (r2 = 0.51, p < .001) and to a lesser extent (B) apnea-hypopnea index (r2 = 0.19, p = .002). Data from the development data set are shown. CPAP = continuous positive airway pressure.

Multivariate linear regression (including therapeutic CPAP, AHI, BMI, age, and sex as independent variables) demonstrated that therapeutic CPAP level and AHI remained the only independent predictors of Pcrit (r2 = 0.57, p < .001, adjusted r2 = 0.52). When assessed against the simple regression including only therapeutic CPAP level, this multivariate model did not significantly improve the prediction of Pcrit (r2 change = 0.07, F[4,40] = 1.51, p = .218), see Table 2. We therefore decided to test the predictive value of the simplest (most parsimonious) model (therapeutic CPAP level alone) for estimating upper airway collapsibility.

Table 2.

Comparison of Linear Regression Models for Determining Pcrit.

| Variable | β | SE of β | βStd | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple model | ||||

| Therapeutic CPAP level | 0.82 | 0.12 | 0.71 | <.001 |

| Multivariate model | ||||

| Therapeutic CPAP level | 0.76 | 0.13 | 0.66 | <.001 |

| AHI | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.28 | .02 |

| BMI | −0.04 | 0.06 | −0.09 | .54 |

| Age | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.04 | .78 |

| Male sex | −0.14 | 0.77 | 0.02 | .86 |

Data from the development data set are shown.

AHI = apnea-hypopnea index; BMI = body mass index; CPAP = continuous positive airway pressure; β = beta efficient; βStd =standardized beta efficient; SE = standard error.

Determining Upper Airway Collapsibility From Therapeutic CPAP Level

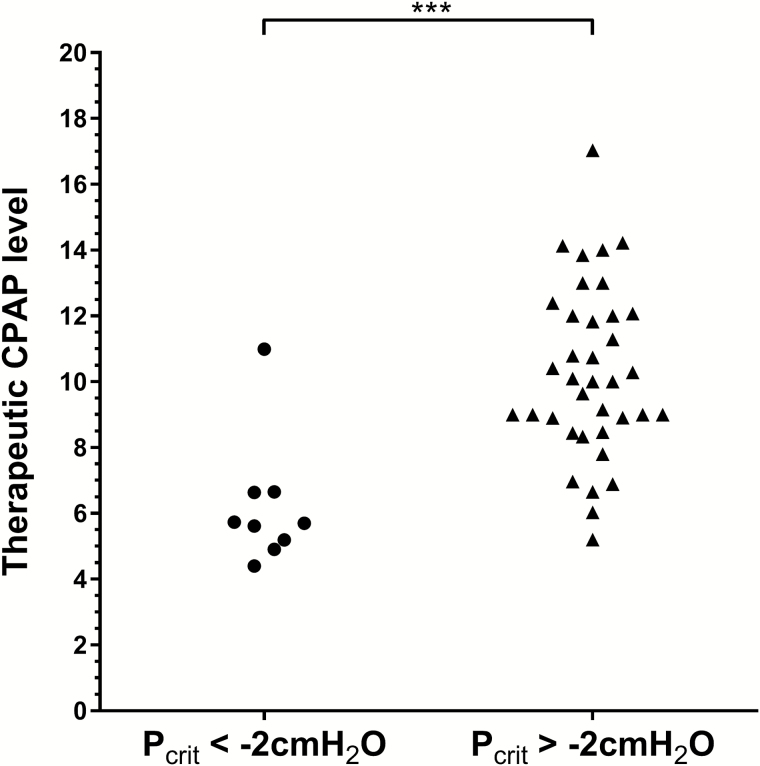

In the development data set, patients with a mildly collapsible upper airway (Pcrit ≤ −2 cmH2O) had a significantly lower therapeutic CPAP level compared to the more collapsible group (Pcrit > −2 cmH2O; t(44) = 4.41, p < .001), see Figure 3. ROC curve analysis using therapeutic CPAP level as the testing variable to predict Pcrit, showed a significant area under the curve (AUC) of 0.91 ± 0.07 (p < .001). The best sensitivity/specificity trade-off was found for therapeutic CPAP levels between 6.0 and 8.0 cmH2O. A therapeutic CPAP level of ≤6.0 cmH2O provided a sensitivity of 67% (confidence interval [CI]: 31%–91%) and a strong specificity of 97% (CI: 84%–100%) to detect a mildly collapsible upper airway. Positive predictive value (PPV) was 86% (CI: 42%–99%), which means that a CPAP level less than or equal to 6.0 cmH2O correctly predicted a Pcrit ≤ −2 cmH2O 86% of the time. Negative predictive value (NPV) was 92% (CI: 78%–98%), that is, CPAP level > 6.0 cmH2O correctly predicted a Pcrit > −2 cmH2O 92% of the time. By comparison, a therapeutic CPAP level of less than or equal to 8.0 provided a sensitivity of 89% (CI: 51%–99%) and a specificity of 84% (67%–93%). PPV was 57% (CI: 30%–81%) and NPV was 97% (CI: 83%–99%). Importantly, those individuals misclassified as having a mildly collapsible airway using these CPAP level thresholds (ie, false positives) still tended to have negative Pcrit values (≤6 cmH2O: −1.5 cmH2O, ≤7 cmH2O: −0.8 ± 0.4 cmH2O, ≤8 cmH2O: −0.3 ± 0.5 cmH2O). Sensitivity and specificity values for each CPAP level (between 4.0 and 16.0 cmH2O) are provided in the online Supplementary Material.

Figure 3.

Comparison of therapeutic CPAP level between participants with mild upper airway collapsibility (Pcrit < −2 cmH2O, circles) and those with moderate-severe collapsibility (Pcrit > −2 cmH2O, triangles). Participants with Pcrit less than −2 cmH2O had a significantly lower therapeutic CPAP level (p < .001), with the majority (8/9) having a CPAP level less than 7 cmH2O. Interestingly, the five participants with a therapeutic CPAP level less than 7 cmH2O but were classed as having a more collapsible airway (Pcrit greater than −2), still had low, mostly negative Pcrit values (−1.53, −1.48, −0.69, −0.72, 0.64 cmH2O). Data from the development data set are shown. CPAP = continuous positive airway pressure.

Assessing the Accuracy of Therapeutic CPAP Level to Predict Upper Airway Collapsibility in an Independent Data Set

In the independent (validation) data set, therapeutic CPAP level was also strongly associated with Pcrit (r2 = 0.54, p < .001), and ROC curve analysis demonstrated a similarly high AUC of 0.88 ± 0.05 (p < .001). See online Supplementary Material for comparison plots between the development and validation data sets. The therapeutic CPAP level cutoff values of 6.0–8.0 cmH2O maintained good predictive accuracy for determining the degree of upper airway collapsibility (Table 3). The specificity and PPV improved (at the expense of reduced sensitivity and NPV) relative to the development data set.

Table 3.

—Comparison of CPAP Cutoff Levels to predict Mild Upper Airway Collapsibility.

| CPAP level | Data set | Sens(%) | Spec (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | Acc (%) | TP (n) | TN (n) | FP (n) | FN (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤6.0 cmH2O | Development set | 67 | 97 | 86 | 92 | 91 | 6 | 36 | 1 | 3 |

| Validation set | 54 | 100 | 100 | 78 | 82 | 15 | 45 | 0 | 13 | |

| ≤7.0 cmH2O | Development set | 89 | 86 | 62 | 97 | 87 | 8 | 32 | 5 | 1 |

| Validation set | 64 | 98 | 95 | 82 | 85 | 18 | 45 | 1 | 10 | |

| ≤8.0 cmH2O | Development set | 89 | 84 | 57 | 97 | 86 | 8 | 31 | 6 | 1 |

| Validation set | 75 | 91 | 84 | 86 | 85 | 21 | 42 | 4 | 7 |

Acc = accuracy of test; FN = false negative; FP = false positive; NPV = negative predictive value; PPV = positive predictive value; Sens = sensitivity; Spec = specific; TN = true negative; TP = true positive.

DISCUSSION

The major finding of our study is that an OSA patient’s therapeutic CPAP requirement provides key information about the collapsibility of their upper airway. Lower therapeutic CPAP levels are associated with more negative Pcrit (less collapsible) values. Specifically, patients with a CPAP requirement below 6–8 cmH2O were highly likely to have a mildly collapsible upper airway (defined by a Pcrit ≤ −2 cmH2O). Importantly, when applied to a separate validation data set, the therapeutic CPAP thresholds we established predicted mild upper airway collapsibility with high specificity and PPV. Although, the association between these variables may seem intuitive, the current findings highlight for the first time the strength and predictive utility of this relationship. In a clinical context, this information could potentially be used by physicians to distinguish between patients in whom a highly collapsible upper airway is a dominant factor contributing to OSA, from those where the upper airway is only mildly collapsible (but abnormalities in one or more nonanatomical traits could be a major causative factor12).

Relationship Between Pcrit and Therapeutic CPAP Level

The present study found a strong positive association between therapeutic CPAP levels and Pcrit in both our development (r2 = 0.51) and validation data (r2 = 0.54). This contrasts with previous work by Sforza et al.,13 who found only a weak association between these variables (r2 ~ 0.07). This discrepancy is likely due to the fact that Sforza et al. measured Pcrit under active neuromuscular conditions, and thus, any associations between Pcrit and therapeutic CPAP level would have been confounded by individual variability in upper airway muscle responsiveness. By contrast, our measurements of Pcrit assessed collapsibility of the upper airway under relatively passive neuromuscular conditions (ie, passive Pcrit14).

A positive association between passive Pcrit and therapeutic CPAP makes intuitive sense when one considers how these variables are defined and measured. Pcrit represents the mask pressure at which the upper airway collapses. The therapeutic CPAP level represents the minimal mask pressure capable of producing nonflow limited (eupneic) ventilation. At mask pressures lower than therapeutic CPAP level, peak inspiratory flow reduces in a linear fashion until flow becomes zero (ie, Pcrit is reached).1 In this way, more positive Pcrit values should be associated with a higher CPAP level required to resolve flow limitation (ie, therapeutic CPAP), similarly more negative Pcrits would be expected to require lower CPAP levels. By extrapolating pressure/flow dynamics from published data in controls, snorers, and people with OSA to a starling resistor model of the upper airway, Gold and Schwartz,15 similarly predicted that a pressure difference of 8 cmH2O would exist between the holding pressure (therapeutic CPAP) and Pcrit. Our observed data confirm this modeled relationship, although we found a slightly wider average differential between Pcrit and the therapeutic CPAP level (median = 8.8, interquartile range [IQR] = 2.6). For this simple relationship between Pcrit and therapeutic CPAP level to exist in our group data, it suggests that reductions in inspiratory flow for any given reduction in mask pressure (ie, the slope of the flow/mask pressure relationship) are similar between individuals. Conversely, our data suggest that the slope of this relationship demonstrates a mild positive association with Pcrit, and that those with greater collapsibility have a significantly steeper gradient to this flow/pressure relationship (see Supplementary Material). This indicates that below the therapeutic CPAP level, small stepped reductions in mask pressure tend to result in lesser reductions in peak flow in those with mild collapsibility, whereas in those with more severe collapsibility, the same reductions in mask pressure tend to result in more significant collapse of the airway, resulting in greater reductions in peak inspiratory flow. Such variation in the slope of the flow/pressure relationship may be related to the mechanism or site of upper airway collapse, although this warrants further investigation.

Relationship Between Pcrit and Demographic/Anthropometric Variables

Contrary to previous investigations,13,16–18 the present study did not find a statistically significant association between Pcrit and BMI nor did we find any difference in Pcrit between males and females. However, the previous documented associations between BMI and Pcrit have been found to be relatively weak (r2 ~ 0.10–0.14), and in some cases, these associations have included patients as well as healthy controls (ie, non-OSA patients).16 Such associations must be interpreted with care as they may not necessarily be as predictive within an OSA only cohort such as that used in the present study. The magnitude of reported sex differences in Pcrit have varied substantially between studies (0.5–1.8 cmH2O) but has tended to be small or only significant in groups matched for BMI.18 Importantly, with regard to the present analysis, for such variables to be useful clinical predictors of upper airway collapsibility, not only must they share a statistically significant association, the association must be strong and account for a large amount of variability in Pcrit. In the present data, the only variable that fit this criterion was therapeutic CPAP level.

OSA Pathophysiology: Importance of Upper Airway Collapsibility

The present findings support to the concept that the therapeutic CPAP level could be used to identify which patients with OSA have a Pcrit < −2 cmH2O, indicating that they have an airway which is only mildly collapsible. In a recent study, designed to identify the pathophysiological causes of OSA in a large cohort of patients, Eckert et al.12 found that 19% of people with OSA studied had mild upper airway collapsibility (defined by a Pcrit < −2 cmH2O), a proportion consistent with that found in our development data set (9/46, 20%) as well as other physiological investigations.19 Importantly, Eckert found that 100% of such patients had abnormalities in one or more of the nonanatomical traits also known to cause OSA (ie, ineffective upper airway muscles responsiveness, hypersensitive ventilatory control, or a low respiratory arousal threshold). Of note was the finding that many control participants were found to have similar airway collapsibility to patients with OSA but did not have OSA, likely due to the absence of these nonanatomical abnormalities. Consistent with this finding, Patil et al.19 reported that all people with OSA they studied had Pcrit values greater than −5 cmH2O but above this threshold found a similar degree of overlap in airway collapsibility between people with OSA and roughly half of their non-OSA control participants. The key factor differentiating individuals in this area of overlap was that the controls had a more robust upper airway muscle response compared to patients with OSA, thus allowing them to overcome their mildly collapsible airway. Together, these studies suggest that individuals with a Pcrit between −5 and −2 cmH2O are vulnerable to developing OSA, but the influence of nonanatomical contributors to OSA pathogenesis can dictate whether or not OSA develops. Thus, OSA patients with mild upper airway collapsibility are likely to be the most appropriate targets for interventions that modify these nonanatomical traits, such as supplemental oxygen to reduce ventilatory control instability20 or hypnotics to increase respiratory arousal threshold.21 In support of this concept, we have recently demonstrated that patients who responded (defined by a reduction in the AHI of 50% and an AHI on therapy <10 events/hour) to the combination of both supplemental oxygen and the hypnotic eszopiclone, had a less collapsible airway (ie, more negative Pcrit) compared to nonresponders.7

Interestingly, mild upper airway collapsibility has also been shown to be predictive of response to anatomically oriented OSA treatments. Recent evidence suggests that patients who are responders to oral appliances also have a less collapsible airway compared to nonresponders.5 This finding is not surprising given that these devices decrease upper airway collapsibility, and the extent to which they can improve OSA severity is related to the degree to which collapsibility reduced.22 Of note, the data of Schwartz et al.6 similarly show that those patients with a lower baseline Pcrit are more likely to have OSA resolved following weight loss. This notion raises the possibility the mild airway collapsibility may also predict responses to other anatomically oriented OSA treatments which have been shown to reduce Pcrit, such as upper airway surgeries23 and sleeping in the lateral position.24

Clinical Implications

The inability to easily measure upper airway collapsibility/Pcrit in a clinical setting is one of the major factors limiting the adoption of these personalized treatment options into clinical practice. The key implication of our study’s findings is that therapeutic CPAP requirement can be used to categorically approximate a given patient’s degree of upper airway collapsibility. In this way, patients likely to have a mild collapsibility may be identified in a clinically practical way, by using existing titration procedures and standard CPAP equipment.

Although our data are retrospective and require further prospective validation, our proposed CPAP level thresholds demonstrate high specificity and PPV, which would allow clinicians to use this information to “rule in” patients into trialing an alternative (non-CPAP) intervention or therapy. CPAP ≤6 cmH2O provided the highest predictive value at “ruling in” mild collapsibility, although thresholds of ≤7 and 8 cmH2O also performed well and would allow a greater proportion of patients to be considered for non-CPAP treatments. Clinicians and researchers can use different thresholds depending on whether the aim is to “rule in” or “rule out” participants with a mildly collapsible airway. It is important to note that in the present data, individuals misclassified as having a mildly collapsible airway using these cutoffs (ie, false positives) still tended to have negative Pcrit values and thus would likely still be amendable to non-CPAP interventions. In support of this concept, Tsuiki et al.25 reported in a Japanese population of people with OSA that therapeutic CPAP levels ranging between 8.5 and 10.5 cmH2O could be used to help judge the likelihood of response to oral appliance therapy. Similar findings, albeit with slightly higher CPAP cutoff values, have also been reported in a predominantly Caucasian sample.26 Conversely, other studies have demonstrated that therapeutic CPAP levels poorly predict oral appliance treatment response27 and do not predict which individuals respond to nasal expiratory positive airway pressure therapy.8

Given the complexity of OSA pathophysiology, it is likely that other physiological factors may be important in predicting the likelihood of therapeutic response. For example, although our data suggest that a patient’s therapeutic CPAP level can provide clinicians with an understanding about whether upper airway collapsibility plays a major or relatively minor role in determining why an individual patient develops OSA, it is important to note that this simplified measure does not provide any information about the specific site of airway collapse. This may be an important factor particularly in determining the efficacy of certain non-CPAP therapies,28,29 thus information regarding the therapeutic CPAP level paired with an otorhinolaryngological examination and/or drug-induced endoscopy30 may produce a more comprehensive understanding of the propensity toward airway collapse. Furthermore, other nonanatomical pathogenic traits may be important factors contributing to OSA in many individuals, particularly those with mild upper airway collapsibility. Fortunately, recent progress has also been made toward simplified measurement of the other contributing traits responsible for OSA. Terrill et al.31 have demonstrated that loop gain (a measure of ventilatory control instability) can be quantified using signals collected routinely in a diagnostic sleep study (EEG, nasal pressure, SaO2, and respiratory effort). In addition, we previously demonstrated that a patient’s arousal threshold can be determined by indices easily obtainable from a diagnostic sleep study report (AHI, nadir oxygen desaturation, and proportion of respiratory events scored as hypopnea compared to apneas).32 Although these tools are clinically feasible and promising, future prospective studies are needed to investigate specifically whether this information can prospectively predict treatment response.

The way in which therapeutic CPAP level is determined is likely to be a critical component contributing to the strength of the predictive relationship we have demonstrated between CPAP level and Pcrit. In the present work, CPAP titration procedures and our definition of the therapeutic CPAP level were based on strict physiological criteria (ie, the minimum pressure capable of eliminating respiratory events and inspiratory flow limitation). Moreover, our therapeutic level and was reassessed/retitrated multiple times to ensure accuracy. It is important for clinicians to carefully consider the specific circumstances and method of CPAP titration performed before attempting to use therapeutic CPAP level data clinically. Given that autotitrating positive airway pressure (APAP) devices use sensitive measurement of flow-limited breathing to titrate pressure, we believe that a therapeutic CPAP level determined from APAP devices (conventionally defined by the 90th/95th percentile pressure statistic) is also likely to predict upper airway collapsibility. It is important to note, however, that differently branded APAP devices are likely to use different algorithms for detecting flow limitation, titrating pressure, and for determining 90th/95th percentile pressure levels. Future prospective work is required to further test the prediction of collapsibility using CPAP level. Such work should investigate how this relationship may change across titration procedures, between manual versus autotitration, and between APAP devices.

Methodological Considerations

When interpreting our findings, there are a number of limitations that must be considered. The current predictive tool was based on data obtained when patients were sleeping in the supine position. It is therefore uncertain whether the relationship between therapeutic CPAP and Pcrit we have demonstrated is generalizable to patients sleeping in the lateral position. However, given that OSA is often less severe, the upper airway less collapsible, and CPAP level requirements are often reduced in the lateral position,33 we expect the supine therapeutic CPAP level will be more useful in defining who will respond to non-CPAP therapies in all sleeping positions.

Many participants in the present study were receiving treatment for OSA (via CPAP or oral appliance) before study procedures, and no washout period was required before they underwent the clinical and research PSGs. Given that the AHI has been shown to remain somewhat reduced for a period (~1 week) following the termination of CPAP therapy,34 our measurement of participant’s AHI may have been underestimated. Importantly, both therapeutic CPAP and upper airway collapsibility appear to be unaffected by this “CPAP washout” effect,35 and thus, this factor is unlikely to have influenced the reported association between therapeutic CPAP level and Pcrit.

Of note, the therapeutic CPAP level derived in each of our participants was accomplished specifically in supine, NREM sleep, while determining Pcrit during a research PSG. It is possible that this CPAP level may differ from values determined during a clinical CPAP titration. In a subset of 27 patients in which we had both measurements, the research PSG derived therapeutic CPAP level (median = 10.7, IQR = 3.07) was slightly higher compared to the physician prescribed CPAP level (median = 10.0, IQR = 4.00, p = .56). However, in each case, the prediction of upper airway collapsibility (mild vs. moderate/severe upper airway collapsibility) was not altered based on whether we used the patient’s prescribed or research determined therapeutic CPAP level.

Conclusions

In summary, our findings show a strong relationship between a patient’s therapeutic CPAP requirement and the underlying severity of upper airway collapsibility. Importantly, we have demonstrated that the therapeutic CPAP level can be used to discriminate between individuals with a mildly collapsible upper airway from those with moderate/severe collapsibility. Although our data need to be confirmed prospectively under different titration conditions, this simple tool has the potential to aid in personalizing the treatment of OSA, by allowing clinicians to screen for and determine which patients are most suitable for individual non-CPAP therapies targeted at treating the underlying causes of OSA.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available at SLEEP online.

FUNDING

Dr. Landry is supported by NeuroSleep, a NHMRC Centre of Research Excellence (1060992) as well as the Monash University Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences postdoctoral bridging Fellowship. Dr Eckert is supported by a NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship (1116942). Dr Jordan is supported by the Australian Research Council (FT100203203). Dr. Sands was supported by the American Heart Association (15SDG25890059), National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (1053201), the Menzies Foundation, American Thoracic Society Foundation, and the National Institute of Health (R01HL128658, 2R01HL102321, P01HL10050580). Dr. Edwards was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia’s CJ Martin Overseas Biomedical Fellowship (1035115) and is now supported by a Heart Foundation of Australia Future Leader Fellowship (101167). Dr. Malhotra is PI on NIH R01HL085188, K24HL132105 and coinvestigator on R21HL121794, R01HL119201, R01HL081823. This work was also supported by Harvard Catalyst (National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health Award UL1TR001102).

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

As an Officer of the American Thoracic Society, Dr. Malhotra has relinquished all outside personal income since 2012. ResMed, Inc. provided a philanthropic donation to the UC San Diego in support of a sleep center. Dr. White was the chief medical officer for Philips Respironics until 12/31/12 but is now a consultant. Dr White is also the chief scientific officer for Apnicure Inc as of January 2013 and a consultant for Night Balance since 2014. A/Prof Hamilton and Dr Joosten have received equipment to support research from ResMed, Philips Respironics and Air Liquide Healthcare. Dr Sands has worked as a consultant for Cambridge Sound Management. All other authors have no conflicts to disclose and do not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Lauren Hess, Erik Smales, Pam DeYoung, Alison Foster, Elizabeth Skuza, and Chris Andara for their laboratory assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1. Gleadhill IC, Schwartz AR, Schubert N, Wise RA, Permutt S, Smith PL. Upper airway collapsibility in snorers and in patients with obstructive hypopnea and apnea. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991; 143(6): 1300–1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wellman A, Jordan AS, Malhotra A, et al. Ventilatory control and airway anatomy in obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004; 170(11): 1225–1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McGinley BM, Schwartz AR, Schneider H, Kirkness JP, Smith PL, Patil SP. Upper airway neuromuscular compensation during sleep is defective in obstructive sleep apnea. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2008; 105(1): 197–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Younes M. Role of arousals in the pathogenesis of obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004; 169(5): 623–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Edwards BA, Andara C, Landry S, et al. Upper-airway collapsibility and loop gain predict the response to oral appliance therapy in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016; 194(11): 1413–1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schwartz AR, Gold AR, Schubert N, et al. Effect of weight loss on upper airway collapsibility in obstructive sleep apnea. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991; 144(3 Pt 1): 494–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Edwards BA, Sands SA, Owens RL, et al. The combination of supplemental oxygen and a hypnotic markedly improves obstructive sleep apnea in patients with a mild to moderate upper airway collapsibility. Sleep. 2016; 39(11): 1973–1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Patel AV, Hwang D, Masdeu MJ, Chen GM, Rapoport DM, Ayappa I. Predictors of response to a nasal expiratory resistor device and its potential mechanisms of action for treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2011; 7(1): 13–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Xie A, Teodorescu M, Pegelow DF, et al. Effects of stabilizing or increasing respiratory motor outputs on obstructive sleep apnea. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2013; 115(1): 22–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.AASM., ESRS., JSSR., LASS. International Classification of Sleep Disorders, Revised: Diagnostic and Coding Manual.2nd Edition ed: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Patil SP, Punjabi NM, Schneider H, O’Donnell CP, Smith PL, Schwartz AR. A simplified method for measuring critical pressures during sleep in the clinical setting. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004; 170(1): 86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Eckert DJ, White DP, Jordan AS, Malhotra A, Wellman A. Defining phenotypic causes of obstructive sleep apnea. Identification of novel therapeutic targets. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013; 188(8): 996–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sforza E, Petiau C, Weiss T, Thibault A, Krieger J. Pharyngeal critical pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Clinical implications. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999; 159(1): 149–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schwartz AR, O’Donnell CP, Baron J, et al. The hypotonic upper airway in obstructive sleep apnea: role of structures and neuromuscular activity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998; 157(4 Pt 1): 1051–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gold AR, Schwartz AR. The pharyngeal critical pressure. The whys and hows of using nasal continuous positive airway pressure diagnostically. Chest. 1996; 110(4): 1077–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kirkness JP, Schwartz AR, Schneider H, et al. Contribution of male sex, age, and obesity to mechanical instability of the upper airway during sleep. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2008; 104(6): 1618–1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Genta PR, Schorr F, Eckert DJ, et al. Upper airway collapsibility is associated with obesity and hyoid position. Sleep. 2014; 37(10): 1673–1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jordan AS, Wellman A, Edwards JK, et al. Respiratory control stability and upper airway collapsibility in men and women with obstructive sleep apnea. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2005; 99(5): 2020–2027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Patil SP, Schneider H, Marx JJ, Gladmon E, Schwartz AR, Smith PL. Neuromechanical control of upper airway patency during sleep. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2007; 102(2): 547–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wellman A, Malhotra A, Jordan AS, Stevenson KE, Gautam S, White DP. Effect of oxygen in obstructive sleep apnea: role of loop gain. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2008; 162(2): 144–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Eckert DJ, Owens RL, Kehlmann GB, et al. Eszopiclone increases the respiratory arousal threshold and lowers the apnoea/hypopnoea index in obstructive sleep apnoea patients with a low arousal threshold. Clin Sci (Lond). 2011; 120(12): 505–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ng AT, Gotsopoulos H, Qian J, Cistulli PA. Effect of oral appliance therapy on upper airway collapsibility in obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003; 168(2): 238–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schwartz AR, Schubert N, Rothman W, et al. Effect of uvulopalatopharyngoplasty on upper airway collapsibility in obstructive sleep apnea. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992; 145(3): 527–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Joosten SA, Edwards BA, Wellman A, et al. The effect of body position on physiological factors that contribute to obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2015; 38(9): 1469–1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tsuiki S, Kobayashi M, Namba K, et al. Optimal positive airway pressure predicts oral appliance response to sleep apnoea. Eur Respir J. 2010; 35(5): 1098–1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sutherland K, Phillips CL, Davies A, et al. CPAP pressure for prediction of oral appliance treatment response in obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014; 10(9): 943–949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dort L, Savard N, Dort E, Dort M, Dort J. Does CPAP pressure predict treatment outcome with oral appliances? Journal of Dental Sleep Medicine. 2017; 04 (01): 113–117. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ng AT, Qian J, Cistulli PA. Oropharyngeal collapse predicts treatment response with oral appliance therapy in obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2006; 29(5): 666–671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vanderveken OM, Maurer JT, Hohenhorst W, et al. Evaluation of drug-induced sleep endoscopy as a patient selection tool for implanted upper airway stimulation for obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013; 9(5): 433–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Croft CB, Pringle M. Sleep nasendoscopy: a technique of assessment in snoring and obstructive sleep apnoea. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1991; 16(5): 504–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Terrill PI, Edwards BA, Nemati S, et al. Quantifying the ventilatory control contribution to sleep apnoea using polysomnography. Eur Respir J. 2015; 45(2): 408–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Edwards BA, Eckert DJ, McSharry DG, et al. Clinical predictors of the respiratory arousal threshold in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014; 190(11): 1293–1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Joosten SA, O’Driscoll DM, Berger PJ, Hamilton GS. Supine position related obstructive sleep apnea in adults: pathogenesis and treatment. Sleep Med Rev. 2014; 18(1): 7–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vroegop AV, Smithuis JW, Benoist LB, Vanderveken OM, de Vries N. CPAP washout prior to reevaluation polysomnography: a sleep surgeon’s perspective. Sleep Breath. 2015; 19(2): 433–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Loewen A, Ostrowski M, Laprairie J, et al. Determinants of ventilatory instability in obstructive sleep apnea: inherent or acquired? Sleep. 2009; 32(10): 1355–1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.