Abstract

Context

The advent of Web-based sports injury surveillance via programs such as the High School Reporting Information Online system and the National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance Program has aided the acquisition of boys' and men's lacrosse injury data.

Objective

To describe the epidemiology of injuries sustained in high school boys' lacrosse in the 2008–2009 through 2013–2014 academic years and collegiate men's lacrosse in the 2004–2005 through 2013–2014 academic years using Web-based sports injury surveillance.

Design

Descriptive epidemiology study.

Setting

Online injury surveillance from lacrosse teams of high school boys (annual average = 55) and collegiate men (annual average = 14).

Patients or Other Participants

Boys' and men's lacrosse players who participated in practices and competitions during the 2008–2009 through 2013–2014 academic years in high school or the 2004–2005 through 2013–2014 academic years in college.

Main Outcome Measure(s)

Athletic trainers collected time-loss (≥24 hours) injury and exposure data. Injury rates per 1000 athlete-exposures (AEs), injury rate ratios (IRRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and injury proportions by body site and diagnosis were calculated.

Results

High School Reporting Information Online documented 1407 time-loss injuries during 662 960 AEs. The National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance Program documented 1882 time-loss injuries during 390 029 AEs. The total injury rate from 2008–2009 through 2013–2014 was higher in college than in high school (3.77 versus 2.12/1000 AEs; IRR = 1.78; 95% CI = 1.63, 1.94). Most injuries occurred during competitions in high school (61.4%) and practices in college (61.4%). Injury rates were higher in competitions compared with practices in high school (IRR = 3.59; 95% CI = 3.23, 4.00) and college (IRR = 3.38; 95% CI = 3.08, 3.71). Lower limb injuries, muscle strains, and ligament sprains were common at both levels. Concussion was the most frequent competition diagnosis for all high school player positions.

Conclusions

Rates of time-loss injury were higher in college versus high school and in competitions versus practices. Attention to preventing common lower leg injuries and concussions, especially at the high school level, is essential to decrease their incidence and severity.

Key Words: concussions, musculoskeletal injuries, muscle strains, injury prevention

Key Points

The injury rate was higher in collegiate men's lacrosse than in high school boys' lacrosse.

Injury rates during competitions exceeded those during practices.

Concussions were the most common competition injury in high school players, whereas ligament sprains were the most common injury in collegiate players.

Lacrosse is a growing sport at both the high school and collegiate levels. In 2013–2014, a reported 106 720 boys participated in lacrosse at the high school level, representing a 77.9% increase from the 59 993 participants in 2004–2005.1 Similarly, participation in men's collegiate lacrosse increased 68.4% from 7313 participants in 2004–2005 to 12 682 in 2013–2014.2 As participation continues to rise, it is important to consider the development of prevention strategies that will help mitigate the increased number of injuries that may result.

Since the 1980s, the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) has used injury surveillance to acquire collegiate sports injury data to assist in the development of evidence-based prevention strategies. Although this NCAA-based surveillance system has had several names, we herein denote it as the NCAA Injury Surveillance Program (ISP). Since the 2004–2005 academic year, the NCAA has used a Web-based platform to collect collegiate sports injury and exposure data via athletic trainers (ATs).3 A year later, High School Reporting Information Online (HS RIO), a similar Web-based high school sports injury-surveillance system, was launched.4

As denoted in the van Mechelen et al5 framework, injury prevention benefits from ongoing monitoring of injury incidence, and updated descriptive epidemiology is needed. Furthermore, over the past decade, rule changes have been enforced to help reduce the incidence of injury. Lastly, few comparisons exist on the injury epidemiology of lacrosse injuries across levels. Differences in age, developmental stage, and level of play must be considered to drive targeted and effective injury-prevention efforts. The purpose of this article is to summarize the descriptive epidemiology of injuries sustained in high school boys' during the 2008–2009 through 2013–2014 academic years and collegiate men's lacrosse during the 2004–2005 through 2013–2014 academic years.

METHODS

Data Sources and Study Period

This study used data collected by HS RIO and the NCAA-ISP for the high school and collegiate levels, respectively. Use of HS RIO data was approved by the Nationwide Children's Hospital Subjects Review Board (Columbus, OH). Use of the NCAA-ISP data was approved by the Research Review Board at the NCAA.

An average of 55 high schools sponsoring boys' lacrosse participated in HS RIO during the 2008–2009 through 2013–2014 academic years (2008–2009 was the first year HS RIO collected data for the sport). An average of 14 NCAA member institutions (Division I = 6, Division II = 1, Division III = 7) sponsoring men's lacrosse participated in the NCAA-ISP during the 2004–2005 through 2013–2014 academic years. The methods of HS RIO and the NCAA-ISP are summarized in the following paragraphs. In-depth information on the methods and analyses used for this special series of articles on Web-based sports injury surveillance can be found in the previously published methodologic article.6 In addition, earlier publications have described the sampling and data collection of HS RIO4,7 and the NCAA-ISP3 in depth.

High School RIO

High School RIO consists of a sample of high schools with 1 or more National Athletic Trainers' Association-affiliated ATs with valid e-mail addresses. The ATs from participating high schools reported injury incidence and athlete-exposure (AE) information weekly throughout the academic year using a secure Web site. For each injury, the AT completed a detailed report on the injured athlete (age, height, weight, etc), the injury (site, diagnosis, severity, etc), and the injury event (activity, mechanism, etc). Throughout each academic year, participating ATs were able to view and update previously submitted reports as needed with new information (eg, time loss).

High School RIO has 2 data-collection panels: a random sample of 100 schools recruited annually since 2005–2006 that report data for the 9 original sports of interest (boys' baseball, basketball, football, soccer, and wrestling and girls' basketball, soccer, softball, and volleyball), and an additional convenience sample of schools recruited annually since 2008–2009 that report data for the additional sports of interest (eg, boys' ice hockey and lacrosse and girls' field hockey and lacrosse). For the first panel, high schools were recruited into 8 strata based on school population (enrollment ≤1000 or >1000) and US Census geographic region.8 If a school dropped out of the system, a replacement from the same stratum was selected. For the second panel, it was impossible to approximate a nationally representative random sample due to strong regional variations in sport sponsorship (eg, ice hockey). As a result, exposure and injury data for the schools in the second panel represent a convenience sample of US high schools. Athletic trainers at some schools from the first panel (those enrolled in the original random sample) chose to report for more than the original 9 sports of interest, and ATs at some of the schools from the second panel reported for some of the original 9 sports as well as the additional sports of interest. Those schools' data provided the original and convenience samples from boys' lacrosse.

National Estimates.

National injury estimate weights were not created for boys' lacrosse, and thus, national estimates could not be computed.

National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance Program

The NCAA-ISP depends on a convenience sample of teams with ATs voluntarily reporting injury and exposure data.3 Participation in the NCAA-ISP, while voluntary, is available to all NCAA institutions. For each injury event, the AT completes a detailed event report on the injury or condition (eg, site, diagnosis) and the circumstances (eg, activity, mechanism, event type [ie, competition or practice]). The ATs are able to view and update previously submitted information as needed during the course of a season. In addition, ATs also provide the number of student-athletes participating in each practice and competition. Data collection for the 2004–2005 through 2013–2014 academic years is described in the following paragraphs.

During the 2004–2005 through 2008–2009 academic years, ATs used a Web-based platform launched by the NCAA to track injury and exposure data.3 This platform integrated some of the functional components of an electronic medical record, such as athlete demographic information and preseason injury information. During the 2009–2010 through 2013–2014 academic years, the Datalys Center for Sports Injury Research and Prevention, Inc (Datalys Center, Indianapolis, IN), introduced a common data element (CDE) standard to improve process flow. The CDE standard allowed data to be gathered from different electronic medical record and injury-documentation applications, including the Athletic Trainer System (Keffer Development, Grove City, PA), Injury Surveillance Tool (Datalys Center), and the Sports Injury Monitoring System (FlanTech, Iowa City, IA). The CDE export standard allowed ATs to document injuries as they normally would as part of their daily clinical practice, as opposed to asking them to report injuries solely for the purpose of participation in an ISP. Data were deidentified and sent to the Datalys Center, where they were examined by data quality-control staff and a verification engine.

National Estimates.

To calculate national estimates of the number of injuries and AEs, poststratification sample weights based upon sport, division, and academic year were applied to each reported injury and AE. Weights for all data were further adjusted to correct for underreporting, consistent with Kucera et al,9 who estimated that the ISP captured 88.3% of all time-loss medical-care injury events. Weighted counts were scaled up by a factor of (0.883−1). In-depth information on the formula used to calculate national estimates can be found in the previously published methodologic article.6

Definitions

Injury.

A reportable injury in both HS RIO and the NCAA-ISP was defined as an injury that (1) occurred as a result of participation in an organized practice or competition, (2) required medical attention by a certified AT or physician, and (3) resulted in restriction of the student-athlete's participation for 1 or more days beyond the day of injury. Since the 2007–2008 academic year, HS RIO has also captured all concussions, fractures, and dental injuries, regardless of time loss. In the NCAA-ISP, multiple injuries occurring from 1 injury event could be included, whereas in HS RIO, only the principal injury was captured. Beginning in the 2009–2010 academic year, the NCAA-ISP also began to monitor all non–time-loss injuries. A non–time-loss injury was defined as any injury that was evaluated or treated (or both) by an AT or physician but did not result in restriction from participation beyond the day of injury. However, because HS RIO captures only time-loss injuries (to reduce the time burden on high school ATs), for this series of publications, only time-loss injuries (with the exception of concussions, fractures, and dental injuries as noted earlier) were included.

Athlete-Exposure.

For both surveillance systems, a reportable AE was defined as 1 student-athlete participating in 1 school-sanctioned practice or competition in which he or she was exposed to the possibility of athletic injury, regardless of the time associated with that participation. Preseason scrimmages were considered practice exposures, not competition exposures.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SAS-Enterprise Guide software (version 5.4; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). Because the data collected from HS RIO and the NCAA-ISP are similar, we opted to recode data when necessary to increase the comparability between high school and collegiate student-athletes. We also opted to ensure that categorizations were consistent among all sport-specific articles within this special series. Because methodologic variations may lead to small differences in injury reporting between these surveillance systems, caution must be taken when interpreting these results.

We examined injury counts, national estimates (for college only), and distributions by event type (practice, competition), time in season (preseason, regular season, postseason), time loss (1–6 days, 7–21 days, more than 21 days, including injuries resulting in a premature end to the season), body part injured, diagnosis, mechanism of injury, activity during injury, and position.

We also calculated injury rates per 1000 AEs and injury rate ratios (IRRs). The IRRs focused on comparisons by level of play (high school and college), event type (practice and competition), school size in high school (≤1000 and >1000 students), division in college (Division I, II, and III), and time in season (preseason, regular season, and postseason). For the IRR comparing high school and college, because HS RIO had data available only for 2008–2009 through 2013–2014, we considered only the NCAA-ISP data from that time period as well. All IRRs with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) not containing 1.0 were considered statistically significant.

Lastly, we used linear regression to analyze linear trends across time for injury rates and compute average annual changes (ie, mean differences). Because of the 2 separate data-collection methods for the NCAA-ISP during the 2004–2005 through 2008–2009 and 2009–2010 through 2013–2014 academic years, linear trends were calculated separately for each time period. All mean differences with 95% CIs not containing 0.0 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Total Injury Frequency and Injury Rates

During the 2008–2009 through 2013–2014 academic years, ATs reported a total of 1407 time-loss injuries in high school boys' lacrosse (Table 1). During the 2004–2005 through 2013–2014 academic years, ATs noted a total of 1882 time-loss injuries in collegiate men's lacrosse. The total injury rate for high school boys' lacrosse was 2.12/1000 AEs (95% CI = 2.01, 2.23). The total injury rate for collegiate men's lacrosse was 4.83/1000 AEs (95% CI = 4.61, 5.04). The total injury rate during 2008–2009 through 2013–2014 was higher in college than in high school (3.77 versus 2.12/1000 AEs; IRR = 1.78; 95% CI = 1.63, 1.94).

Table 1.

Injury Rates by School Size or Division and Type of Athlete-Exposure in High School Boys' and Collegiate Men's Lacrossea

| Surveillance System and School Size or Division |

Exposure Type |

Injuries in Sample, No. (%) |

Athlete- Exposures |

Injury Rate/1000 Athlete-Exposures (95% Confidence Interval) |

| HS RIO (2008–2009 through 2013–2014) | ||||

| ≤1000 students | Practice | 303 (40.5) | 191 094 | 1.59 (1.41, 1.76) |

| Competition | 446 (59.5) | 80 012 | 5.57 (5.06, 6.09) | |

| Total | 749 (100.0) | 271 106 | 2.76 (2.56, 2.96) | |

| >1000 students | Practice | 240 (36.5) | 268 292 | 0.89 (0.78, 1.01) |

| Competition | 418 (63.5) | 123 562 | 3.38 (3.06, 3.71) | |

| Total | 658 (100.0) | 391 854 | 1.68 (1.55, 1.81) | |

| Total | Practice | 543 (38.6) | 459 386 | 1.18 (1.08, 1.28) |

| Competition | 864 (61.4) | 203 574 | 4.24 (3.96, 4.53) | |

| Total | 1407 (100.0) | 662 960 | 2.12 (2.01, 2.23) | |

| NCAA-ISP (2004–2005 through 2013–2014) | ||||

| Division I | Practice | 646 (65.9) | 192 052 | 3.36 (3.10, 3.62) |

| Competition | 334 (34.1) | 29 031 | 11.50 (10.27, 12.74) | |

| Total | 980 (100.0) | 221 082 | 4.43 (4.16, 4.71) | |

| Division II | Practice | 29 (70.7) | 9812 | 2.96 (1.88, 4.03) |

| Competition | 12 (29.3) | 2493 | 4.81 (2.09, 7.54) | |

| Total | 41 (100.0) | 12 305 | 3.33 (2.31, 4.35) | |

| Division III | Practice | 480 (55.7) | 126 923 | 3.78 (3.44, 4.12) |

| Competition | 381 (44.3) | 29 719 | 12.82 (11.53, 14.11) | |

| Total | 861 (100.0) | 156 642 | 5.50 (5.13, 5.86) | |

| Total | Practice | 1155 (61.4) | 328 787 | 3.51 (3.31, 3.72) |

| Competition | 727 (38.6) | 61 242 | 11.87 (11.01, 12.73) | |

| Total | 1882 (100.0) | 390 029 | 4.83 (4.61, 5.04) | |

Abbreviations: HS RIO, High School Reporting Information Online; NCAA-ISP, National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance Program.

High school data originated from HS RIO surveillance data, 2008–2009 through 2013–2014; collegiate data originated from the NCAA-ISP surveillance data, 2004–2005 through 2013–2014. Injuries included in the analysis were those that (1) occurred during a sanctioned practice or competition; (2) were evaluated or treated (or both) by an athletic trainer, physician, or other health care professional; and (3) restricted the student-athlete from participation for at least 24 hours past the day of injury. All concussions, fractures, and dental injuries were included in the analysis, regardless of time loss. Data may include multiple injuries that occurred at 1 injury event. The athlete-exposures may not sum to totals due to rounding error.

School Size and Division

In high school, the total injury rate was higher in high schools with ≤1000 students than in high schools with >1000 students (IRR = 1.65; 95% CI = 1.48, 1.83; Table 1). In college, Division III had a higher total injury rate than Division I (IRR = 1.24; 95% CI = 1.13, 1.36) and Division II (IRR = 1.65; 95% CI = 1.21, 2.26). Injury rates did not differ between Divisions I and II (IRR = 1.33; 95% CI = 0.97, 1.82).

Event Type

The majority of injuries occurred during competitions in high school (61.4%) and practices in college (61.4%; Table 1). The competition injury rate was higher than the practice injury rate in high school (IRR = 3.59; 95% CI = 3.23, 4.00) and college (IRR = 3.38; 95% CI = 3.08, 3.71).

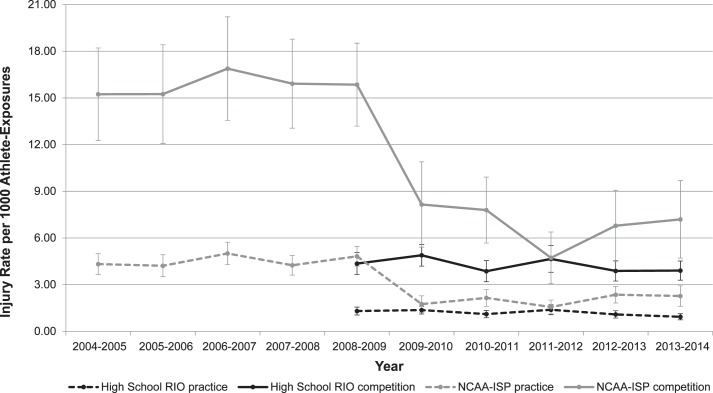

Decreases occurred in high school practice injury rates (annual average change of −0.07/1000 AEs; 95% CI = −0.12, −0.01) but not high school competition injury rates (annual average change of −0.13/1000 AEs; 95% CI = −0.29, 0.03; Figure). No linear trends were found in the 2004–2005 through 2008–2009 academic years for collegiate practices (annual average change of 0.10/1000 AEs; 95% CI = −0.08, 0.28) or competitions (annual average change of 0.19/1000 AEs; 95% CI = −0.14, 0.52). No linear trends were seen in the 2009–2010 through 2013–2014 academic years for collegiate practices (annual average change of 0.12/1000 AEs; 95% CI = −0.03, 0.28) or competitions (annual average change of −0.29/1000 AEs; 95% CI = −0.99, 0.41).

Figure.

Injury rates by year and type of athlete-exposure (AE) in high school boys' and collegiate men's lacrosse. Annual average changes for linear trend test for injury rates are as follows: High School Reporting Information Online (RIO; practices = −0.07/1000 AEs; 95% confidence interval [CI] = −0.12, −0.01; competitions = −0.13/1000 AEs; 95% CI = −0.29, 0.03); National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance Program (NCAA-ISP) 2004–2005 through 2008–2009 (practices = 0.10/1000 AEs; 95% CI = −0.08, 0.28; competitions = 0.19/1000 AEs; 95% CI = −0.14, 0.52); NCAA-ISP 2009–2010 through 2013–2014 academic years (practices = 0.12/1000 AEs; 95% CI = −0.03, 0.28; competitions = −0.29/1000 AEs; 95% CI = −0.99, 0.41). A negative rate indicates a decrease in annual average change between years, and a positive rate indicates an increase in annual average change; 95% CIs that include 0.00 were not significant.

Time in Season

For both high school and collegiate players, most injuries occurred during the regular season (high school = 77.6%, college = 58.9%; Table 2). In college, the preseason had a higher injury rate than the regular season (IRR = 1.15; 95% CI = 1.04, 1.26) and postseason (IRR = 1.82; 95% CI = 1.45, 2.29). In addition, the injury rate was higher during the regular season than during the postseason (IRR = 1.59; 95% CI = 1.27, 1.99). Injury rates by time in season could not be calculated for high school as AEs were not stratified by time in season.

Table 2.

Injury Rates by Time in Season and Type of Athlete-Exposure in High School Boys' and Collegiate Men's Lacrossea

| Time in Season |

Event Type |

HS RIO (2008–2009 Through 2013–2014) |

NCAA-ISP (2004–2005 Through 2013–2014) |

||

| Injuries in Sample, No. (%) |

Injuries in Sample, No. (%) |

Athlete- Exposures |

Injury Rate/1000 Athlete-Exposures (95% Confidence Interval) |

||

| Preseason | Practice | 226 (77.9) | 675 (97.4) | 126 686 | 5.33 (4.93, 5.73) |

| Competition | 64 (22.1) | 18 (2.6) | 1458 | 12.35 (6.64, 18.05) | |

| Total | 290 (100.0) | 693 (100.0) | 128 144 | 5.41 (5.01, 5.81) | |

| Regular season | Practice | 312 (28.7) | 438 (39.5) | 179 874 | 2.44 (2.21, 2.66) |

| Competition | 776 (71.3) | 670 (60.5) | 54 750 | 12.24 (11.31, 13.16) | |

| Total | 1088 (100.0) | 1108 (100.0) | 234 625 | 4.72 (4.44, 5.00) | |

| Postseason | Practice | 4 (16.7) | 42 (51.9) | 22 226 | 1.89 (1.32, 2.46) |

| Competition | 20 (83.3) | 39 (48.1) | 5034 | 7.75 (5.32, 10.18) | |

| Total | 24 (100.0) | 81 (100.0) | 27 260 | 2.97 (2.32, 3.62) | |

Abbreviations: HS RIO, High School Reporting Information Online; NCAA-ISP, National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance Program.

Excluded 5 injuries reported in HS RIO due to missing data for time in season. Injury rates by time in season could not be calculated for high school as athlete-exposures were not stratified by time in season. The athlete-exposures may not sum to totals due to rounding error. High school data originated from HS RIO surveillance data, 2008–2009 through 2013–2014; collegiate data originated from the NCAA-ISP surveillance data, 2004–2005 through 2013–2014. Injuries included in the analysis were those that (1) occurred during a sanctioned practice or competition; (2) were evaluated or treated (or both) by an athletic trainer, physician, or other health care professional; and (3) restricted the student-athlete from participation for at least 24 hours past the day of injury. All concussions, fractures, and dental injuries were included in the analysis, regardless of time loss. Data may include multiple injuries that occurred at 1 injury event.

Time Loss From Participation

In both high school and college, the largest proportion of injuries resulted in time loss of less than 1 week, ranging from 36.6% of injuries in high school competitions to 52.5% of injuries in collegiate competitions (Table 3).

Table 3.

Number of Injuries and Injury Rates by Time Loss and Type of Athlete-Exposure in High School Boys' and Collegiate Men's Lacrossea

| Surveillance System and Time-Loss Category |

Practices |

Competitions |

||

| Injuries in Sample, No. (%) |

Injury Rate/1000 Athlete-Exposures (95% Confidence Interval) |

Injuries in Sample, No. (%) |

Injury Rate/1000 Athlete-Exposures (95% Confidence Interval) |

|

| HS RIO (2008–2009 through 2013–2014) | ||||

| 1 d to <1 wk | 229 (44.0) | 0.50 (0.43, 0.56) | 302 (36.6) | 1.48 (1.32, 1.65) |

| 1 to 3 wk | 178 (34.2) | 0.39 (0.33, 0.44) | 276 (33.5) | 1.36 (1.20, 1.52) |

| >3 wkb | 114 (21.9) | 0.25 (0.20, 0.29) | 247 (29.9) | 1.21 (1.06, 1.36) |

| NCAA-ISP (2004–2005 through 2013–2014) | ||||

| 1 d to <1 wk | 550 (48.6) | 1.67 (1.53, 1.81) | 373 (52.5) | 6.09 (5.47, 6.71) |

| 1 to 3 wk | 357 (31.6) | 1.09 (0.97, 1.20) | 217 (30.6) | 3.54 (3.07, 4.01) |

| >3 wkb | 224 (19.8) | 0.68 (0.59, 0.77) | 120 (16.9) | 1.96 (1.61, 2.31) |

Abbreviations: HS RIO, High School Reporting Information Online; NCAA-ISP, National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance Program.

Excluded 61 injuries reported in HS RIO and 41 injuries reported in the NCAA-ISP due to missing data for time loss. Percentages may not add up to 100.0 due to rounding error. High school data originated from HS RIO surveillance data, 2008–2009 through 2013–2014; collegiate data originated from the NCAA-ISP surveillance data, 2004–2005 through 2013–2014. Injuries included in the analysis were those that (1) occurred during a sanctioned practice or competition; (2) were evaluated or treated (or both) by an athletic trainer, physician, or other health care professional; and (3) restricted the student-athlete from participation for at least 24 hours past the day of injury. All concussions, fractures, and dental injuries were included in the analysis, regardless of time loss. Data may include multiple injuries that occurred at 1 injury event.

Included injuries that resulted in time loss over 3 weeks, medical disqualification, the athlete choosing not to continue, the athlete being released from the team, or the season ending before the athlete returned to activity.

Body Parts Injured and Diagnoses

High School.

The most commonly injured body part during both practices and competitions was the head/face (practices = 16.8%, competitions = 31.9%; Table 4). Other frequently injured body parts were the knee (13.8%), hip/thigh/upper leg (13.4%), and ankle (12.0%) during practices and the shoulder/clavicle (12.9%) and knee (10.4%) during competitions. The most often cited injury diagnoses were muscle/tendon strains (22.7%) and ligament sprains (18.6%) during practices and concussions (28.8%), ligament sprains (19.4%), and contusions (15.6%) during competitions (Table 5).

Table 4.

Number of Injuries and Injury Rates by Body Part Injured and Type of Athlete-Exposure in High School Boys' and Collegiate Men's Lacrossea

| Surveillance System and Body Part Injured |

Practices |

Competitions |

||

| Injuries in Sample, No. (%) |

Injury Rate/1000 Athlete-Exposures (95% Confidence Interval) |

Injuries in Sample, No. (%) |

Injury Rate/1000 Athlete-Exposures (95% Confidence Interval) |

|

| HS RIO (2008–2009 through 2013–2014) | ||||

| Head/face | 91 (16.8) | 0.20 (0.16, 0.24) | 274 (31.9) | 1.35 (1.19, 1.51) |

| Neck | 9 (1.7) | 0.02 (0.01, 0.03) | 15 (1.7) | 0.07 (0.04, 0.11) |

| Shoulder/clavicle | 41 (7.6) | 0.09 (0.06, 0.12) | 111 (12.9) | 0.55 (0.44, 0.65) |

| Arm/elbow | 15 (2.8) | 0.03 (0.02, 0.05) | 26 (3.0) | 0.13 (0.08, 0.18) |

| Hand/wrist | 44 (8.1) | 0.10 (0.07, 0.12) | 74 (8.6) | 0.36 (0.28, 0.45) |

| Trunk | 33 (6.1) | 0.07 (0.05, 0.10) | 63 (7.3) | 0.31 (0.23, 0.39) |

| Hip/thigh/upper leg | 73 (13.4) | 0.16 (0.12, 0.20) | 74 (8.6) | 0.36 (0.28, 0.45) |

| Knee | 75 (13.8) | 0.16 (0.13, 0.20) | 89 (10.4) | 0.44 (0.35, 0.53) |

| Lower leg | 54 (9.9) | 0.12 (0.09, 0.15) | 31 (3.6) | 0.15 (0.10, 0.21) |

| Ankle | 65 (12.0) | 0.14 (0.11, 0.18) | 80 (9.3) | 0.39 (0.31, 0.48) |

| Foot | 30 (5.5) | 0.07 (0.04, 0.09) | 17 (2.0) | 0.08 (0.04, 0.12) |

| Other | 13 (2.4) | 0.03 (0.01, 0.04) | 6 (0.7) | 0.03 (0.01, 0.05) |

| NCAA-ISP (2004–2005 through 2013–2014) | ||||

| Head/face | 97 (8.4) | 0.30 (0.24, 0.35) | 119 (16.4) | 1.94 (1.59, 2.29) |

| Neck | 16 (1.4) | 0.05 (0.02, 0.07) | 16 (2.2) | 0.26 (0.13, 0.39) |

| Shoulder/clavicle | 84 (7.3) | 0.26 (0.20, 0.31) | 84 (11.6) | 1.37 (1.08, 1.66) |

| Arm/elbow | 12 (1.0) | 0.04 (0.02, 0.06) | 21 (2.9) | 0.34 (0.20, 0.49) |

| Hand/wrist | 92 (8.0) | 0.28 (0.22, 0.34) | 54 (7.4) | 0.88 (0.65, 1.12) |

| Trunk | 99 (8.6) | 0.30 (0.24, 0.36) | 46 (6.3) | 0.75 (0.53, 0.97) |

| Hip/thigh/upper leg | 251 (21.7) | 0.76 (0.67, 0.86) | 129 (17.7) | 2.11 (1.74, 2.47) |

| Knee | 156 (13.5) | 0.47 (0.40, 0.55) | 99 (13.6) | 1.62 (1.30, 1.93) |

| Lower leg | 76 (6.6) | 0.23 (0.18, 0.28) | 34 (4.7) | 0.56 (0.37, 0.74) |

| Ankle | 193 (16.7) | 0.59 (0.50, 0.67) | 100 (13.8) | 1.63 (1.31, 1.95) |

| Foot | 53 (4.6) | 0.16 (0.12, 0.20) | 23 (3.2) | 0.38 (0.22, 0.53) |

| Other | 26 (2.3) | 0.08 (0.05, 0.11) | 2 (0.3) | 0.03 (0.00, 0.08) |

Abbreviations: HS RIO, High School Reporting Information Online; NCAA-ISP, National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance Program.

Excluded 4 injuries reported in HS RIO due to missing data for body part. Percentages may not add up to 100.0 due to rounding error. High school data originated from HS RIO surveillance data, 2008–2009 through 2013–2014; collegiate data originated from the NCAA-ISP surveillance data, 2004–2005 through 2013–2014. Injuries included in the analysis were those that (1) occurred during a sanctioned practice or competition; (2) were evaluated or treated (or both) by an athletic trainer, physician, or other health care professional; and (3) restricted the student-athlete from participation for at least 24 hours past the day of injury. All concussions, fractures, and dental injuries were included in the analysis, regardless of time loss. Data may include multiple injuries that occurred at 1 injury event.

Table 5.

Number of Injuries and Injury Rates by Diagnosis and Type of Athlete-Exposure in High School Boys' and Collegiate Men's Lacrossea

| Surveillance System and Diagnosis |

Practices |

Competitions |

||

| Injuries in Sample, No. (%) |

Injury Rate/1000 Athlete-Exposures (95% Confidence Interval) |

Injuries in Sample, No. (%) |

Injury Rate/1000 Athlete-Exposures (95% Confidence Interval) |

|

| HS RIO (2008–2009 through 2013–2014) | ||||

| Concussion | 75 (13.8) | 0.16 (0.13, 0.20) | 248 (28.8) | 1.22 (1.07, 1.37) |

| Contusion | 65 (12.0) | 0.14 (0.11, 0.18) | 134 (15.6) | 0.66 (0.55, 0.77) |

| Dislocationb | 9 (1.7) | 0.02 (0.01, 0.03) | 22 (2.6) | 0.11 (0.06, 0.15) |

| Fracture/avulsion | 59 (10.9) | 0.13 (0.10, 0.16) | 108 (12.5) | 0.53 (0.43, 0.63) |

| Laceration | 10 (1.9) | 0.02 (0.01, 0.04) | 25 (2.9) | 0.12 (0.07, 0.17) |

| Ligament sprain | 101 (18.6) | 0.22 (0.18, 0.26) | 167 (19.4) | 0.82 (0.70, 0.94) |

| Muscle/tendon strain | 123 (22.7) | 0.27 (0.22, 0.32) | 95 (11.0) | 0.47 (0.37, 0.56) |

| Other | 100 (18.5) | 0.22 (0.18, 0.26) | 62 (7.2) | 0.30 (0.23, 0.38) |

| NCAA-ISP (2004–2005 through 2013–2014) | ||||

| Concussion | 72 (6.3) | 0.22 (0.17, 0.27) | 104 (14.3) | 1.70 (1.37, 2.02) |

| Contusion | 121 (10.5) | 0.37 (0.30, 0.43) | 138 (19.0) | 2.25 (1.88, 2.63) |

| Dislocationb | 16 (1.4) | 0.05 (0.02, 0.07) | 10 (1.4) | 0.16 (0.06, 0.26) |

| Fracture/avulsion | 63 (5.5) | 0.19 (0.14, 0.24) | 50 (6.9) | 0.82 (0.59, 1.04) |

| Laceration | 18 (1.6) | 0.05 (0.03, 0.08) | 13 (1.8) | 0.21 (0.10, 0.33) |

| Ligament sprain | 308 (26.7) | 0.94 (0.83, 1.04) | 207 (28.5) | 3.38 (2.92, 3.84) |

| Muscle/tendon strain | 293 (25.4) | 0.89 (0.79, 0.99) | 117 (16.1) | 1.91 (1.56, 2.26) |

| Other | 261 (22.7) | 0.79 (0.70, 0.89) | 88 (12.1) | 1.44 (1.14, 1.74) |

Abbreviations: HS RIO, High School Reporting Information Online; NCAA-ISP, National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance Program.

Excluded 4 injuries reported in HS RIO and 3 injuries reported in the NCAA-ISP due to missing data for diagnosis. Percentages may not add up to 100.0 due to rounding error. High school data originated from HS RIO surveillance data, 2008–2009 through 2013–2014; collegiate data originated from the NCAA-ISP surveillance data, 2004–2005 through 2013–2014. Injuries included in the analysis were those that (1) occurred during a sanctioned practice or competition; (2) were evaluated or treated (or both) by an athletic trainer, physician, or other health care professional; and (3) restricted the student-athlete from participation for at least 24 hours past the day of injury. All concussions, fractures, and dental injuries were included in the analysis, regardless of time loss. Data may include multiple injuries that occurred at 1 injury event.

Included separations.

College.

The most commonly injured body part during both practices and competitions was the hip/thigh/upper leg (practices = 21.7%, competitions = 17.7%; Table 4). Other frequently injured body parts were the ankle (16.7%) and knee (13.5%) during practices and the head/face (16.4%), ankle (13.8%), and knee (13.6%) during competitions. The injury diagnosed most often during practices and competitions was ligament sprains (practices: 26.7%, competitions: 28.5%; Table 5). Other common injury diagnoses were muscle/tendon strains (25.4%) during practices and contusions (19.0%), muscle/tendon strains (16.1%), and concussions (14.3%) during competitions.

Mechanisms of Injury and Activities

High School.

The most common injury mechanisms during practices and competitions were contact with another person (practices = 25.8%, competitions = 52.3%) and no contact (practices = 27.2%, competitions = 17.0%; Table 6). During competitions, 12.3% of injuries were due to contact with the stick. The most frequent activities during injury in practices and competitions were general play (practices and competitions both = 49.3%; Table 7). The general-play category consisted of injuries that occurred during body checking (practices = 27, competitions = 73), stick checking (practices = 5, competitions = 27), being body checked (practices = 33, competitions = 95), and being stick checked (practices = 27, competitions = 68). Other common activities during injury were conditioning (11.3%) in practices and chasing loose balls (10.1%) in competitions.

Table 6.

Number of Injuries and Injury Rates by Mechanism of Injury and Type of Athlete-Exposure in High School Boys' and Collegiate Men's Lacrossea

| Surveillance System and Mechanism of Injury |

Practices |

Competitions |

||

| Injuries in Sample, No. (%) |

Injury Rate/1000 Athlete-Exposures (95% Confidence Interval) |

Injuries in Sample, No. (%) |

Injury Rate/1000 Athlete-Exposures (95% Confidence Interval) |

|

| HS RIO (2008–2009 through 2013–2014) | ||||

| Contact with another person | 137 (25.8) | 0.30 (0.25, 0.35) | 447 (52.3) | 2.20 (1.99, 2.40) |

| Contact with playing surface | 57 (10.8) | 0.12 (0.09, 0.16) | 81 (9.5) | 0.40 (0.31, 0.48) |

| Contact with ball | 54 (10.2) | 0.12 (0.09, 0.15) | 44 (5.1) | 0.22 (0.15, 0.28) |

| Contact with goal | 1 (0.2) | <0.01 (0.00, 0.01) | 1 (0.1) | <0.01 (0.00, 0.01) |

| Contact with the stick | 32 (6.0) | 0.07 (0.05, 0.09) | 105 (12.3) | 0.52 (0.42, 0.61) |

| Contact with other playing equipment | 4 (0.8) | 0.01 (0.00, 0.02) | 9 (1.1) | 0.04 (0.02, 0.07) |

| Contact with out of bounds object | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 |

| No contact | 144 (27.2) | 0.31 (0.26, 0.36) | 145 (17.0) | 0.71 (0.60, 0.83) |

| Overuse/chronic | 92 (17.4) | 0.20 (0.16, 0.24) | 20 (2.3) | 0.10 (0.06, 0.14) |

| Illness/infection | 9 (1.7) | 0.02 (0.01, 0.03) | 3 (0.4) | 0.01 (0.00, 0.03) |

| NCAA-ISP (2004–2005 through 2013–2014) | ||||

| Contact with another person | 261 (22.8) | 0.79 (0.70, 0.89) | 328 (45.5) | 5.36 (4.78, 5.94) |

| Contact with playing surface | 96 (8.4) | 0.29 (0.23, 0.35) | 73 (10.1) | 1.19 (0.92, 1.47) |

| Contact with ball | 87 (7.6) | 0.26 (0.21, 0.32) | 29 (4.0) | 0.47 (0.30, 0.65) |

| Contact with goal | 2 (0.2) | 0.01 (0.00, 0.01) | 1 (0.1) | 0.02 (0.00, 0.05) |

| Contact with the stick | 82 (7.2) | 0.25 (0.20, 00.3) | 69 (9.6) | 1.13 (0.86, 1.39) |

| Contact with other playing equipment | 3 (0.3) | 0.01 (0.00, 0.02) | 2 (0.3) | 0.03 (0.00, 0.08) |

| Contact with out of bounds object | 4 (0.4) | 0.01 (0.00, 0.02) | 1 (0.1) | 0.02 (0.00, 0.05) |

| No contact | 496 (43.4) | 1.51 (1.38, 1.64) | 200 (27.7) | 3.27 (2.81, 3.72) |

| Overuse/chronic | 89 (7.8) | 0.27 (0.21, 0.33) | 18 (2.5) | 0.29 (0.16, 0.43) |

| Illness/infection | 23 (2.0) | 0.07 (0.04, 0.10) | 0 | 0.00 |

Abbreviations: HS RIO, High School Reporting Information Online; NCAA-ISP, National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance Program.

Mechanism of injury excluded 22 injuries reported in HS RIO and 18 injuries reported in the NCAA-ISP due to missing data or athletic trainer reporting Other or Unknown. Percentages may not add up to 100.0 due to rounding error. High school data originated from HS RIO surveillance data, 2008–2009 through 2013–2014; collegiate data originated from the NCAA-ISP surveillance data, 2004–2005 through 2013–2014. Injuries included in the analysis were those that (1) occurred during a sanctioned practice or competition; (2) were evaluated or treated (or both) by an athletic trainer, physician, or other health care professional; and (3) restricted the student-athlete from participation for at least 24 hours past the day of injury. All concussions, fractures, and dental injuries were included in the analysis, regardless of time loss. Data may include multiple injuries that occurred at 1 injury event.

Table 7.

Number of Injuries and Injury Rates by Activity During Injury and Type of Athlete-Exposure in High School Boys' and Collegiate Men's Lacrossea

| Surveillance System and Activity During Injury |

Practices |

Competitions |

||

| Injuries in Sample, No. (%) |

Injury Rate/1000 Athlete-Exposures (95% Confidence Interval) |

Injuries in Sample, No. (%) |

Injury Rate/1000 Athlete-Exposures (95% Confidence Interval) |

|

| HS RIO (2008–2009 through 2013–2014) | ||||

| Ball handling | 24 (4.8) | 0.05 (0.03, 0.07) | 56 (6.9) | 0.28 (0.20, 0.35) |

| Blocking | 17 (3.4) | 0.04 (0.0, 0.05) | 11 (1.4) | 0.05 (0.02, 0.09) |

| Conditioning | 57 (11.3) | 0.12 (0.09, 0.16) | 0 | 0.00 |

| Defending | 44 (8.7) | 0.10 (0.07, 0.12) | 80 (9.8) | 0.39 (0.31, 0.48) |

| Faceoff | 2 (0.4) | <0.01 (0.00, 0.01) | 21 (2.6) | 0.10 (0.06, 0.15) |

| General play | 248 (49.3) | 0.54 (0.47, 0.61) | 401 (49.3) | 1.97 (1.78, 2.16) |

| Goaltending | 20 (4.0) | 0.04 (0.02, 0.06) | 33 (4.1) | 0.16 (0.11, 0.22) |

| Loose ball | 46 (9.1) | 0.10 (0.07, 0.13) | 82 (10.1) | 0.40 (0.32, 0.49) |

| Passing | 13 (2.6) | 0.03 (0.01, 0.04) | 31 (3.8) | 0.15 (0.10, 0.21) |

| Receiving pass | 13 (2.6) | 0.03 (0.01, 0.04) | 43 (5.3) | 0.21 (0.15, 0.27) |

| Shooting | 19 (3.8) | 0.04 (0.02, 0.06) | 55 (6.8) | 0.27 (0.20, 0.34) |

| NCAA-ISP (2004–2005 through 2013–2014) | ||||

| Ball handling | 121 (10.7) | 0.37 (0.30, 0.43) | 97 (13.6) | 1.58 (1.27, 1.90) |

| Blocking | 17 (1.5) | 0.05 (0.03, 0.08) | 8 (1.1) | 0.13 (0.04, 0.22) |

| Conditioning | 101 (8.9) | 0.31 (0.25, 0.37) | 1 (0.1) | 0.02 (0.00, 0.05) |

| Defending | 168 (14.9) | 0.51 (0.43, 0.59) | 126 (17.6) | 2.06 (1.70, 2.42) |

| Faceoff | 13 (1.2) | 0.04 (0.02, 0.06) | 30 (4.2) | 0.49 (0.31, 0.67) |

| General play | 492 (43.5) | 1.50 (1.36, 1.63) | 238 (33.2) | 3.89 (3.39, 4.38) |

| Goaltending | 39 (3.5) | 0.12 (0.08, 0.16) | 10 (1.4) | 0.16 (0.06, 0.26) |

| Loose ball | 74 (6.6) | 0.23 (0.17, 0.28) | 94 (13.1) | 1.53 (1.22, 1.85) |

| Passing | 13 (1.2) | 0.04 (0.02, 0.06) | 19 (2.7) | 0.31 (0.17, 0.45) |

| Receiving pass | 24 (2.1) | 0.07 (0.04, 0.10) | 20 (2.8) | 0.33 (0.18, 0.47) |

| Shooting | 68 (6.0) | 0.21 (0.16, 0.26) | 73 (10.2) | 1.19 (0.92, 1.47) |

Abbreviations: HS RIO, High School Reporting Information Online; NCAA-ISP, National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance Program.

Activity excluded 91 injuries reported in HS RIO and 36 injuries reported in the NCAA-ISP due to missing data or athletic trainer reporting Other or Unknown. Percentages may not add up to 100.0 due to rounding error. High school data originated from HS RIO surveillance data, 2008–2009 through 2013–2014; collegiate data originated from the NCAA-ISP surveillance data, 2004–2005 through 2013–2014. Injuries included in the analysis were those that (1) occurred during a sanctioned practice or competition; (2) were evaluated or treated (or both) by an athletic trainer, physician, or other health care professional; and (3) restricted the student-athlete from participation for at least 24 hours past the day of injury. All concussions, fractures, and dental injuries were included in the analysis, regardless of time loss. Data may include multiple injuries that occurred at 1 injury event.

College.

The most common mechanisms of injury during both practices and competitions were contact with another person (practices = 22.8%, competitions = 45.5%) and no contact (practices = 43.4%, competitions = 27.7%; Table 6). The most frequent activities during injury in practices and competitions were general play (practices = 43.5%, competitions = 33.2%), defending (practices = 14.9%, competitions = 17.6%), and ball handling (practices = 10.7%, competitions = 13.6%; Table 7). General-play injuries consisted of 12 checking injuries in practices and 6 checking injuries in competitions.

Position-Specific Injuries in Competitions

In high school competitions, the most common injuries among all positions were concussions, many of which were due to contact with another player (Table 8). In collegiate competitions, hip/thigh/upper leg strains were the most frequent injury to defenders (16.3%) and goalkeepers (20.8%), whereas concussions were the most often cited injury to attackers (17.2%) and midfielders (15.1%).

Table 8.

Most Common Injuries Associated With Position in Competitions in High School Boys' and Collegiate Men's Lacrossea

| Position |

HS RIO (2008–2009 Through 2013–2014) |

NCAA-ISP (2004–2005 Through 2013–2014) |

||||

| Most Common Injuries |

Injuries Within Position (%) |

Most Frequent Mechanism of Injury for This Injury Within Position |

Most Common Injuries |

Injuries Within Position (%) |

Most Frequent Mechanism of Injury for This Injury Within Position |

|

| Attacker | Concussion | 22.5 | Contact with another person | Concussion | 17.2 | Contact with another person |

| Ankle sprain | 8.2 | No contact | Ankle sprain | 14.4 | Contact with another person | |

| Shoulder sprain | 8.4 | Contact with another person | ||||

| Defense | Concussion | 29.8 | Contact with another person | Hip/thigh/upper leg muscle strain | 16.3 | No contact |

| Ankle sprain | 11.1 | No contact | Ankle sprain | 12.7 | No contact | |

| Concussion | 9.6 | Contact with another person | ||||

| Knee sprain | 9.6 | Contact with another person | ||||

| Goalkeeper | Concussion | 31.7 | Contact with another person | Hip/thigh/upper leg muscle strain | 20.8 | No contact |

| Hand/wrist fracture/avulsion | 19.5 | Contact with ball | Hand/wrist fracture/avulsion | 12.5 | Contact with ball | |

| Knee sprain | 12.5 | No contact | ||||

| Midfielder | Concussion | 31.1 | Contact with another person | Concussion | 15.1 | Contact with another person |

| Ankle sprain | 7.0 | Contact with another person, no contact (tied) | Ankle sprain | 12.2 | No contact | |

| Hip/thigh/upper leg muscle strain | 11.8 | No contact | ||||

Abbreviations: HS RIO, High School Reporting Information Online; NCAA-ISP, National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance Program.

Excluded 47 competition injuries reported in HS RIO and 43 competition injuries reported in the NCAA-ISP due to position not being indicated. The table reads as follows: For the attacker position in high school, concussions comprised 22.5% of all competition injuries to that position. The most common mechanism of injury for this specific injury for this specific position was contact with another person. High school data originated from HS RIO surveillance data, 2008–2009 through 2013–2014; collegiate data originated from the NCAA-ISP surveillance data, 2004–2005 through 2013–2014. Injuries included in the analysis were those that (1) occurred during a sanctioned practice or competition; (2) were evaluated or treated (or both) by an athletic trainer, physician, or other health care professional; and (3) restricted the student-athlete from participation for at least 24 hours past the day of injury. All concussions, fractures, and dental injuries were included in the analysis, regardless of time loss. Data may include multiple injuries that occurred at 1 injury event.

DISCUSSION

Lacrosse is one of the fastest growing team sports at both the high school and collegiate levels.1 Both boys' and men's lacrosse are equipment-intensive collision sports that mandate helmets, mouth guards, shoulder and arm pads, and padded gloves due to continued contact with other players and equipment (ie, the stick, ball).10 Given the dramatic rise in popularity over the past decade and the full-contact nature of the sport, focusing on injury prevention for lacrosse athletes is essential. Injury rates in lacrosse have been relatively high in previous reports. In 2013–2014, boys' lacrosse also had the seventh highest injury rate out of 20 high school sports at 1.68 injuries per 1000 AEs.11 From 2009–2010 through 2013–2014, men's collegiate lacrosse had the seventh highest injury rate out of 25 NCAA sports at 6.5 injuries per 1000 AEs.12 Ours was the first study, to our knowledge, to examine the rates and patterns of injury in both high school boys' and collegiate men's lacrosse using comparable surveillance systems.

Comparison With Previous Research and Changes Over Time

A 3-year prospective study13 of high school athletes yielded competition and practice injury rates of 4.44 and 1.40/1000 AEs, respectively; these are very similar to our findings of 4.24 and 1.18/1000 AEs during competitions and practices, respectively. Another group14 observed competition and practice injury rates of 4.45 and 1.29/1000 AEs, respectively, in high school lacrosse players. Although we noted rates of injury similar to those of prior investigators, these comparisons are limited to sparse research on boys' lacrosse that supplied injury rates as opposed to the many authors15–18 who reported only specific injuries, patients with injuries presenting to emergency departments, or case studies.

In collegiate players, we found injury rates of 11.87 and 3.51/1000 AEs during competitions and practices, respectively. Authors of a prior NCAA study19 on men's lacrosse reported slightly higher rates during competitions (12.58/1000 AEs) and slightly lower rates during practices (3.24/1000 AEs); competition rates from 1988–1998 through 2003–2004 ranged from 9.2 to 17.3/1000 AEs, while practice rates ranged from 2.6 to 4.0/1000 AEs. Similar to the high school literature, other studies of collegiate lacrosse mainly focused on individual injuries rather than overall rates.15,18,20,21

Although the injury rate in high school boys' lacrosse remained stable over the course of the decade, the injury rate in collegiate men's lacrosse declined significantly from 15.3/1000 AEs in 2004–2005 to 7.4/1000 AEs in 2013–2014, with a sudden decrease from 2008–2009 to 2009–2010. This could be the result of the NCAA-ISP changing its data-collection procedures or injury-prevention efforts by the NCAA that also took place during that time. In 2009, the NCAA Rules Committee asked referees to more stringently penalize head and neck contact.22 In the 2011–2012 season, that rule was formalized and prohibited players from targeting the head or neck. A study19 of lacrosse injuries from 1988–1989 through 2003–2004 using comparable surveillance methods indicated that 45.9% of injuries were due to contact with another player. We found that proportion to be 31.6%, reflecting that either player-player contact decreased or the rules were being more strictly enforced.

In recent years, attention has focused on achieving a better understanding of the injury epidemiology of high school boys' and collegiate men's lacrosse to guide policy decisions that enhance the health and safety of players. The various lacrosse governing bodies (NCAA, National Federation of State High School Associations, and US Lacrosse) have enacted a variety of equipment standards (helmet, chest protector, and ball [http://nocsae.org/standards/lacrosse/]), and rule changes (no contact to the head or neck, no defenseless hits, mandatory mouth guards, etc) to reduce the risk of injury. In addition, education and certification programs for coaches and officials have been emphasized at the youth level to promote a full understanding and consistent enforcement of rules and advances in training approaches (www.uslacrosse.org/coaches/coach-development-program). These active efforts may have directly contributed to the lower injury rates. Although these changes are encouraging, we were unable to assess the specific effects of such rule changes and policy recommendations; therefore, continued monitoring of injury rates and patterns over time is essential to evaluate their effectiveness.

Event Type

Overall, collegiate lacrosse players had higher rates of injury than high school players (Table 1). This finding aligns with previous literature15,23–26 comparing other contact sports across the age spectrum, which suggested that athletes at higher levels of play may be more competitive and play more aggressively and, therefore, be injured more frequently. This might reflect a more time-intensive and rigorous practice schedule for collegiate athletes, which could improve their skills and potentially reduce contact-related injuries but increase the likelihood of noncontact and overuse injuries. High school athletes may also be more skeletally immature than collegiate athletes, increasing their susceptibility to injury. Furthermore, collegiate athletes may have better neuromuscular control compared with high school athletes, either through biological development or the continued practice of neuromuscular-control exercises, which may serve to reduce the severity of injuries.27,28 Taken together, our results suggest that although collegiate athletes have higher rates of injury, we must pay attention to high school athletes, who are still developing their skills and are also at risk for injury.

The discrepancy in injury rates is also likely influenced by increased exposure time during college. In high school, boys play 4 quarters of 12 minutes each at the varsity level, whereas in college, quarters are 15 minutes (48- versus 60-minute games). Because the definition of AE is the same at both levels, differences in rates could reflect playing time. We also found that a greater percentage of injuries occurred during competitions in high school, whereas a greater percentage of injuries occurred during practices in college. This could be due to increased time practicing at the collegiate level relative to time spent competing, allowing more injuries to occur during practices.24 In addition, it is possible that some injuries at the high school level were not reported given that not every AT at every high school could be at every practice; the NCAA recommends the presence of an AT at all collegiate practices and competitions. Collegiate ATs may have reported more injuries when an AT was dedicated to each team, as opposed to 1 AT covering multiple sports or all sports within 1 school.

Type of Injury

Injury patterns in our study were similar to those in previous lacrosse research13–15: the most commonly injured body parts at the high school level were the head/face, lower leg/ankle/foot, and knee. Collegiate lacrosse athletes most often sustained injuries to the hip/thigh/upper leg, ankle, and knee, which is also consistent with prior studies10,15,21,26 showing that lower extremity injuries represented the greatest burden (Table 4). Ligament sprains and muscle/tendon strains were typical in both high school and collegiate players, similar to previous research (Table 5).12,15,21 Given that high school and collegiate data originated from 2 different study periods (2008–2009 through 2013–2014 and 2004–2005 through 2013–2014, respectively), we urge caution in interpreting these findings. Nevertheless, our findings in conjunction with those of previous investigations highlight the fact that ligament sprains continue to be prevalent; more prevention efforts are needed to protect vulnerable joints. The US Lacrosse Association has developed LaxPrep,29 a warmup and exercise program that aims to decrease the lower extremity injury risk in lacrosse players. The effectiveness of the program is currently being examined.

The shoulders are vulnerable to injury in lacrosse as both contact and regular overhead activities are common.17,30 Shoulder and clavicle injuries were not unusual in this analysis, comprising 10.8% of high school and 8.9% of collegiate injuries, similar to prior studies (Table 4).14,30,31 Although it is important to develop proper techniques to protect the shoulder joint while passing or shooting, the most frequent mechanism of injury for shoulder injury at both the collegiate and high school levels was contact with another player, further emphasizing the need for safe contact strategies in this full-contact sport. As in NCAA football, male lacrosse players may benefit from safety-related recommendations that limit the amount of contact during practices.32

In our study, the most striking difference in type of injury between levels of play was observed for concussions (Table 5). Boys' lacrosse had the third highest rate of concussions among 22 high school sports, behind boys' football and ice hockey, but men's lacrosse ranked 13th among 25 collegiate sports.33,34 Consistent with prior research,33–35 the rate of concussion was higher during competitions than practices for both high school and collegiate athletes. However, we also saw differences in the proportions of injuries that were concussions in high school and collegiate athletes. Concussions sustained during practices comprised 13.8% of injuries in high school athletes and 6.3% of injuries in collegiate athletes. Similarly, during competitions, concussions comprised 28.8% of injuries in high school athletes and 14.3% of injuries in collegiate athletes. As previously noted, caution must be taken when interpreting these findings as the high school and collegiate data originated from 2 different study periods (2008–2009 through 2013–2014 and 2004–2005 through 2013–2014, respectively). Nevertheless, such a discrepancy between levels may be concerning because additional studies suggest that younger athletes take longer to recover after sustaining concussions. Kerr et al36 found that, in football, high school athletes with concussions who returned to play in 30 days or more constituted the largest proportion (19.5%) compared with youth (16.3%) and college (7.0%). Zuckerman et al37 demonstrated that athletes aged 13–16 years took longer to return to symptom baselines than those 18–22 years old. Conversely, another group38 found no significant age differences in the rates of acute clinical recovery. A possible explanation could be differences in postconcussion management; ATs and physicians who treat high school athletes may take a more conservative approach when considering return to play, as current guidelines suggest.39 Other extrinsic factors may include a lower skill level at the high school than the collegiate level, as well as differences in rules enforcement in competitions and the nature of contact allowed in practices. Given the lack of research, future studies of male lacrosse players should better address such potential predictors and correlates of concussion to identify prevention strategies to reduce the incidence of this injury. The effectiveness of recently enacted rules aimed at reducing direct contact to the head by the body or the stick should also be examined in longitudinal analyses.

Limitations

Our findings may not be generalizable to other playing levels, such as youth, middle school, and professional programs, nor to collegiate programs at non-NCAA institutions or high schools without National Athletic Trainers' Association-affiliated ATs. Furthermore, we were unable to account for factors potentially associated with injury occurrence, such as AT coverage, implemented injury-prevention programs, and athlete-specific characteristics (eg, previous injury, neuromuscular control, functional capabilities). Also, although HS RIO and the NCAA-ISP are similar injury-surveillance systems, it is important to consider the variations that do exist between them. In addition, differences may exist between high school and college in regard to the length of the season in total, as well as the preseason, regular season, and postseason; the potentially longer collegiate season may increase the injury risk. We calculated injury rates using AEs, which may not be as precise an at-risk exposure measure as minutes, hours, or total number of game plays across a season. However, collecting such exposure data is more laborious than collecting AE data and may be too burdensome for ATs collecting data for both HS RIO and the NCAA-ISP. We also caution about comparisons of injury distributions between the high school and collegiate levels as high school data were not available for the 2004–2005 through 2007–2008 academic years.

Although our study is one of few, to our knowledge, to examine injury incidence across multiple levels of play (eg, high school versus college and competition versus practice), we were unable to examine differences between starters and nonstarters during competitions; analyses that group both types of players may confound and thus weaken the possible exposure-outcome association for some known injury risk factors. Differences may also exist among the freshman, junior varsity, and varsity teams due to maturation status. Playing positions may vary in physical demands and resulting injury risk. Athlete-exposures were not collected by position, preventing the calculation of position-specific injury rates.

CONCLUSIONS

Continual sports injury surveillance across the age spectrum and levels of play is critical for identifying areas for injury prevention. Furthermore, accurate comparison of injury patterns across the age spectrum would not be possible without similar surveillance system methods. Given that data collection for high school lacrosse did not begin until the 2008–2009 academic year, continued examination of lacrosse injuries at both levels will aid in conducting stronger comparative analyses. Despite this limitation, we found evidence of similarities across age groups, with lower extremity injuries representing a large burden of injury in both collegiate and high school athletes. Concussions continue to represent a disproportionate amount of injuries at the high school level during competitions. Coaches and ATs should closely monitor player contact at the high school level to reduce the frequency and severity of injuries. At the collegiate level, monitoring activity during practices is important to detect changing trends in the incidence of noncontact injuries. Continual monitoring of rates and patterns of injuries across the age spectrum is essential for developing prevention efforts and measuring their effectiveness over time.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The NCAA-ISP data were provided by the Datalys Center for Sports Injury Research and Prevention, Inc. The NCAA-ISP was funded by the NCAA. Funding for HS RIO was provided in part by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention grants R49/CE000674-01 and R49/CE001172-01 and the National Center for Research Resources award KL2 RR025754. The authors also acknowledge the research funding contributions of the National Federation of State High School Associations (Indianapolis, IN), National Operating Committee on Standards for Athletic Equipment (Overland Park, KS), DonJoy Orthotics (Vista, CA), and EyeBlack (Potomac, MD). The content of this report is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding organizations. We thank the many ATs who have volunteered their time and efforts to submit data to HS RIO and the NCAA-ISP. Their efforts are greatly appreciated and have had a tremendously positive effect on the safety of high school and collegiate student-athletes.

REFERENCES

- 1.2013–14 high school athletics participation survey. National Federation of State High School Associations Web site. http://www.nfhs.org/ParticipationStatics/PDF/2013-14_Participation_Survey_PDF.pdf Published 2014. Accessed May 10, 2017.

- 2.2013–14 NCAA sports sponsorship and participation rates report. National Collegiate Athletic Association Web site. http://www.ncaapublications.com/productdownloads/PR1314.pdf Accessed April 26, 2017.

- 3.Kerr ZY, Dompier TP, Snook EM, et al. National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance System: review of methods for 2004–2005 through 2013–2014 data collection. J Athl Train. 2014;49(4):552–560. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-49.3.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Sports-related injuries among high school athletes–United States, 2005–06 school year. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(38):1037–1040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Mechelen W, Hlobil H, Kemper HC. Incidence, severity, aetiology and prevention of sports injuries: a review of concepts. Sports Med. 1992;14(2):82–99. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199214020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kerr ZY, Comstock RD, Dompier TP, Marshall SW. The first decade of web-based sports injury surveillance (2004–2005 through 2013–2014): methods of the National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance Program and High School Reporting Information Online. J Athl Train. 2018;53(8):729–737. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-143-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rechel JA, Yard EE, Comstock RD. An epidemiologic comparison of high school sports injuries sustained in practice and competition. J Athl Train. 2008;43(2):197–204. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.2.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Census regions of the United States. US Census Bureau Web site. http://www.census.gov/const/regionmap.pdf Published 2009. Accessed April 14, 2017.

- 9.Kucera KL, Marshall SW, Bell DR, DiStefano MJ, Goerger CP, Oyama S. Validity of soccer injury data from the National Collegiate Athletic Association's Injury Surveillance System. J Athl Train. 2011;46(5):489–499. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-46.5.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCulloch PC, Bach BR., Jr Injuries in men's lacrosse. Orthopedics. 2007;30(1):29–34. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20070101-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Comstock RD, Currie DW, Pierpoint LA. Convenience sample summary report: National High School Sports-related Injury Surveillance Study, 2013–2014 school year. University of Colorado Denver Web site. http://www.ucdenver.edu/academics/colleges/PublicHealth/research/ResearchProjects/piper/projects/RIO/Documents/2013-14%20Convenience%20Report.pdf Published 2014. Accessed May 10, 2017.

- 12.Kerr ZY, Marshall SW, Dompier TP, Corlette J, Klossner DA, Gilchrist J. College sports–related injuries—United States, 2009–10 through 2013–14 academic years. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(48):1330–1336. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6448a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hinton RY, Lincoln AE, Almquist JL, Douoguih WA, Sharma KM. Epidemiology of lacrosse injuries in high school-aged girls and boys: a 3-year prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(9):1305–1314. doi: 10.1177/0363546504274148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiang J, Collins CL, Liu D, McKenzie LB, Comstock RD. Lacrosse injuries among high school boys and girls in the United States: academic years 2008–2009 through 2011–2012. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(9):2082–2088. doi: 10.1177/0363546514539914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vincent HK, Zdziarski LA, Vincent KR. Review of lacrosse-related musculoskeletal injuries in high school and collegiate players. Sports Health. 2015;7(5):448–451. doi: 10.1177/1941738114552990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lincoln AE, Caswell SV, Almquist JL, Dunn RE, Hinton RY. Video incident analysis of concussions in boys' high school lacrosse. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(4):756–761. doi: 10.1177/0363546513476265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wasser JG, Chen C, Vincent HK. Kinematics of shooting in high school and collegiate lacrosse players with and without low back pain. Orthop J Sports Med. 2016;4(7):2325967116657535. doi: 10.1177/2325967116657535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diamond PT, Gale SD. Head injuries in men's and women's lacrosse: a 10 year analysis of the NEISS database. National Electronic Injury Surveillance System. Brain Inj. 2001;15(6):537–544. doi: 10.1080/02699050010007362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dick R, Romani WA, Agel J, Case JG, Marshall SW. Descriptive epidemiology of collegiate men's lacrosse injuries: National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance System, 1988–1989 through 2003–2004. J Athl Train. 2007;42(2):255–261. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lincoln AE, Hinton RY, Almquist JL, Lager SL, Dick RW. Head, face, and eye injuries in scholastic and collegiate lacrosse: a 4-year prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(2):207–215. doi: 10.1177/0363546506293900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mihata LC, Beutler AI, Boden BP. Comparing the incidence of anterior cruciate ligament injury in collegiate lacrosse, soccer, and basketball players: implications for anterior cruciate ligament mechanism and prevention. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(6):899–904. doi: 10.1177/0363546505285582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Collegiate Athletic Association. 2010 NCAA men's lacrosse annual meeting: summary of changes – approved. http://fs.ncaa.org/Docs/rules/mlax/2010/2011-12approvedruleschangesmemo.pdf Accessed January 23, 2017.

- 23.Yard EE, Collins CL, Dick RW, Comstock RD. An epidemiologic comparison of high school and college wrestling injuries. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(1):57–64. doi: 10.1177/0363546507307507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shankar PR, Fields SK, Collins CL, Dick RW, Comstock RD. Epidemiology of high school and collegiate football injuries in the United States, 2005–2006. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(8):1295–1303. doi: 10.1177/0363546507299745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gessel LM, Fields SK, Collins CL, Dick RW, Comstock RD. Concussions among United States high school and collegiate athletes. J Athl Train. 2007;42(4):495–503. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Webb M, Davis C, Westacott D, Webb R, Price J. Injuries in elite men's lacrosse: an observational study during the 2010 world championships. Orthop J Sports Med. 2014;2(7):2325967114543444. doi: 10.1177/2325967114543444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Myer GD, Faigenbaum AD, Ford KR, Best TM, Bergeron MF, Hewett TE. When to initiate integrative neuromuscular training to reduce sports-related injuries and enhance health in youth? Curr Sports Med Rep. 2011;10(3):155–166. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0b013e31821b1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chappell JD, Limpisvasti O. Effect of a neuromuscular training program on the kinetics and kinematics of jumping tasks. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(6):1081–1086. doi: 10.1177/0363546508314425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.LaxPrep. US Lacrosse Web site. http://www.uslacrosse.org/coaches/coaching-education-program/online-courses/laxprep Published 2017. Accessed May 5, 2017.

- 30.Gardner EC, Chan WW, Sutton KM, Blaine TA. Shoulder injuries in men's collegiate lacrosse, 2004–2009. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(10):2675–2681. doi: 10.1177/0363546516644246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yard EE, Comstock RD. Injuries sustained by pediatric ice hockey, lacrosse, and field hockey athletes presenting to United States emergency departments, 1990–2003. J Athl Train. 2006;41(4):441–449. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.2014 year-round football practice contact recommendations. National Collegiate Athletic Association Web site. http://www.ncaa.org/sites/default/files/2014%20Year-Round%20Football_20170117.pdf Published 2014. Accessed May 16, 2017.

- 33.Marar M, McIlvain NM, Fields SK, Comstock RD. Epidemiology of concussions among United States high school athletes in 20 sports. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(4):747–755. doi: 10.1177/0363546511435626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zuckerman SL, Kerr ZY, Yengo-Kahn A, Wasserman E, Covassin T, Solomon GS. Epidemiology of sports-related concussion in NCAA athletes from 2009–2010 to 2013–2014: incidence, recurrence, and mechanisms. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(11):2654–2662. doi: 10.1177/0363546515599634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marshall SW, Guskiewicz KM, Shankar V, McCrea M, Cantu RC. Epidemiology of sports-related concussion in seven US high school and collegiate sports. Inj Epidemiol. 2015;2(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s40621-015-0045-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kerr ZY, Zuckerman SL, Wasserman EB, Covassin T, Djoko A, Dompier TP. Concussion symptoms and return to play time in youth, high school, and college American football athletes. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(7):647–653. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zuckerman SL, Lee YM, Odom MJ, Solomon GS, Forbes JA, Sills AK. Recovery from sports-related concussion: Days to return to neurocognitive baseline in adolescents versus young adults. Surg Neurol Int. 2012;3:130. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.102945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nelson LD, Guskiewicz KM, Barr WB, et al. Age differences in recovery after sport-related concussion: a comparison of high school and collegiate athletes. J Athl Train. 2016;51(2):142–152. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-51.4.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCrory P, Meeuwisse WH, Aubry M, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport: the 4th International Conference on Concussion in Sport, Zurich, November 2012. J Athl Train. 2013;48(4):554–575. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-48.4.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]