Abstract

The relationship literature describes that declining commitment leads to breakup. The goal of this manuscript is to distinguish declining commitment and breakup to clarify this claim to better understand relationship processes. Data comes from a longitudinal study of heterosexual dating couples (N = 180). Both individuals in the relationship independently graphed changes in commitment to wed their partner and reported reasons for each change monthly for eight consecutive months. Frequency and intensity of decreased interaction, relational uncertainty, and alternative partners were measured across periods of stability (increased or stable levels of commitment to wed) and declining commitment (decreased commitment to wed that was at least one month in duration). Hierarchical linear models revealed that more frequent reports of these characteristics were associated with declining commitment rather than stability. Using survival analyses, intensity of each characteristic predicted breakup versus declining commitment. Implications for relationship processes are discussed.

Keywords: commitment, commitment to wed, breakup, dating

Ending a relationship is a common and often difficult experience in the context of dating (Rhoades, Kamp Dush, Atkins, Stanley, & Markman, 2011; Simon & Barrett, 2010; Slotter, Gardner, & Finkel, 2010; Weisskirch & Delevi, 2012). However, few studies have differentiated breaking up from declining commitment, as some couples experience declining commitment but do not break up (Kellas, Bean, Cunningham, & Cheng, 2008; Reed, 2007). Although researchers acknowledge that breaking up is a process involving declining commitment (Sprecher 1994, Vangelisti, 2006), the literature has focused on breakup as an outcome rather than investigating the processes that precede breakup (Barber, 2006; Connolly & McIsaac, 2009). The focus of breakup as an end point has left a gap in knowledge about the process of declining commitment that precedes breakup, particularly regarding individuals that experience declines in commitment but do not breakup. By fleshing out these processes, researchers will not only gain a better comprehension of the process of breaking up, but will more fully understand how individuals experience declining commitment. Subsequently, information about the experience of declining commitment will provide couples with the tools to benefit their relationships in the long-run. Information from this study will also assist clinicians and practitioners working with couples that experience declining commitment and want to maintain their relationships.

The goal of this study is to identify characteristics that distinguish declining commitment from breakup using commitment to wed among heterosexual dating couples. We focus on dating couples because finding a stable, committed relationship is important for identity development (Erikson, 1980) and for developing a romantic self-concept (Slotter et al., 2010). Also, we use commitment to wed as the variable to differentiate declining commitment from breakup. Commitment is a multidimensional phenomenon, as definitions vary from a focus on long-term orientation (Rusbult, 1980), an intent to continue a relationship (Kelley, 1983), moral obligation to persist with the relationship (Johnson, 1999), and dedication (Stanley & Markman, 1992). For dating couples, long-term orientation has been a significant predictor of relationship functioning (Ogolsky & Surra, 2014), which means that the experience of commitment is distinct for dating couples. The expectation of future continuation and questions about whether the relationship will continue is fundamental in dating relationships (Surra, Hughes, & Jacquet, 1999). The bulk of the literature on heterosexual relationships focuses on global commitment; however, considerations for commitment vary according to relationship context. For instance, commitment to marrying and commitment to long-term cohabitation are likely to be different, as commitment to marrying demonstrates higher dedication to the relationship versus cohabitating (Ogolsky & Surra, 2014). Likewise, commitment to wed is likely to differ from more general evaluations of global commitment in that asking partners to consider their commitment to marrying is likely to prompt more serious consideration of relationship quality, structural constraints, and longevity due to the increased focus on continuation and the potential costliness of divorce (Ogolsky & Surra, 2014; Surra & Hughes, 1997). In addition, commitment can be operationalized as “chance of marriage” as this definition includes the belief that a partner would like to continue the relationship without the partner reporting changes in commitment. Therefore, for this study, we adopted Surra and Hughes’ (1997) measure of commitment to wed, where individuals graph their chance of marriage over a monthly period, to differentiate declining commitment and breakup. We operationalize commitment to wed as “chance of marriage,” an estimate of participants’ belief that the relationship will result in marriage.

While some might question the focus on commitment to wed in an age where cohabitation is on the rise (Lichter, Turner, & Sassler, 2010; Manning & Stykes, 2014), it may be that what appears to be a decline in marriage for most individuals is, in fact, a delay in marriage (Manning, Brown, & Payne, 2014). The age at first marriage has continued to rise (Payne, 2014), the age at which cohabitations are formed has remained stable (Manning & Stykes, 2014), and most marriages are preceded by cohabitation (Tach & Halpern-Meekin, 2009). Whether the delay of marriage to later ages is, in fact a rejection of marriage over the entire lifespan remains to be seen. Meanwhile, the formation of marital unions, which we measured as commitment to wed, continues to be an important question in the study of how relationships are formed, persist, or deteriorate. Although assuming that all individuals plan to get married at the time of the interview is a limitation, we believe that having participants graph their chances of marrying their partner is more likely to prompt a serious consideration of the longevity and quality of the relationship that would be more difficult to capture if using subjective measures of commitment, measures of global commitment, or relationship satisfaction (Ogolsky & Surra, 2014).

Issues with Current Frameworks

According to traditional and contemporary models of breakup, couples generally experience periods of declining commitment prior to breakup (e.g. Kellas et al., 2008; Lee, 1984; Rhoades et al., 2011; Sprecher, 1994). In some models, prior to breaking up, an individual decides whether or not to stay in the relationship, meaning that the process of declining commitment may not always lead to the event of breaking up (Duck, 1981; Reed, 2007). Following declines in commitment, it is possible that a relationship will return to its previous level of commitment (Dailey, Rossetto, Pfiester, & Surra, 2009; Rusbult, Agnew, & Arriaga, 2012) or will increase commitment levels, potentially prompting increased confidence in the ability to conquer stressful relationship experiences (Agnew & VanderDrift, 2015).

The first step in being able to differentiate declining commitment from breakup is to define declining commitment using commitment to wed. Before a breakup occurs, a relationship is likely to show signs of instability that impact the long-term continuation of the relationship (Le & Agnew, 2003; Simon & Barrett, 2010). Instability results in negative changes for relationships where one or both partners question the future of the relationship (Surra & Bohman, 1991). Thus, declining commitment is a period during which individuals experience some form of instability that leads to a decline in commitment to wed their partner. This deduction suggests that (a) declining commitment may be preceded by stability, a period during which commitment to wed is increasing or maintaining steady levels and (b) declining commitment begins when commitment to wed decreases subsequent to stability.

It is important to differentiate fluctuations in relationships from instability of commitment. We argue that instability reflects a pattern of decline that is evidenced by declines reported over a longer period of time whereas fluctuations are more fleeting changes in relationship experiences. Research has shown that fluctuations in relationship satisfaction or uncertainty about a relationship occur even on a daily basis and are normative (Arriaga, 2001; Arriaga, Reed, Goodfriend, & Agnew, 2006). Individuals have reported daily changes in satisfaction resulting from a variety of experiences, such as disagreements with a romantic partner (Peterson, 2002) or jealousy (Salovey & Rodin, 1988). These experiences are commonly followed by attempts to repair the relationship rather than consideration to end the relationship (Agnew & VanderDrift, 2015). However, changes in commitment to wed a partner are not as fluid as satisfaction (Ogolsky & Surra, 2014; Surra et al., 1999). Changes in commitment to wed demonstrate instability to the degree that partners consider ending the relationship versus remaining in the relationship (Ogolsky & Surra, 2014; Surra & Bohman, 1991). Therefore, the experience of declining commitment to wed that last at least one month in duration should demonstrate periods of declining commitment that is different from fluctuations in relationships.

The end of declining commitment occurs when commitment to wed ceases to decline. Consistent in many models of breakup is deciding whether to stay in the relationship or break up (Duck, 1981; Slotter et al., 2010; VanderDrift, Agnew, & Wilson, 2009). Therefore, the end of declining commitment occurs with a (a) breakup, which we define as no longer committed to wed a romantic partner, or (b) post-declining commitment, which is reflected by increasing or maintaining a steady level of commitment to wed after declining commitment.

Identifying Characteristics to Differentiate Declining Commitment and Breakup Using Investment Theory

One of the fundamental approaches to understanding decreasing levels of commitment is Rusbult’s (1980; 1983) investment theory. According to this theory, individuals who invest less in their relationships, report less satisfaction, and give more attention to alternative partners decrease their commitment to their partner. Based on previous assumptions – that declining commitment is defined by decreasing commitment to wed – attention to alternative partners should be more apparent during declining commitment than periods of stability. Evidence supports the association between attention to alternatives and decreasing commitment (Miller, 2008; VanderDrift et al., 2009). An alternative is described as an attractive option individuals perceive they have if the current relationship were to end (Rusbult, 1980; 1983; VanderDrift et al., 2009). Alternatives may include a new partner, reuniting with an old partner, or being single, which are commonly viewed as threats to relationships that result in decreased commitment (Rhoades et al., 2011; Rusbult, 1980; 1983). Researchers also describe that attention to alternative partners is associated with breakup (Le & Agnew, 2003; Rusbult et al., 2012; VanderDrift et al., 2009). Connolly and McIsaac (2009) used self-reports to show that alternative partners were one of the major reasons participants ended their romantic relationship. However, to our knowledge, no studies have investigated how some experiences with alternative partners do not result in breakup. For example, a partner who fantasizes about a former partner versus a partner who commits sexual infidelity likely will have different implications for the relationship (VanderDrift et al., 2009). Subsequently, an individual’s own experiences with alternative partners as opposed to an individual’s partner’s experiences with alternative partners should also have repercussions for declining commitment. Therefore, understanding the varied influences of alternative partners should assist in differentiating stability, declining commitment, and breakup.

The investment model of commitment also describes the importance of relationship satisfaction in predicting commitment and breakup. Relationship satisfaction is directly related to the quality of romantic relationships – less satisfied individuals are in lower quality relationships and vice versa (Rusbult 1980; 1983). However, relationship quality and commitment are two distinct motivations for breaking up (Schoebi, Karney, & Bradbury, 2012); therefore, indicators of the investment model and relationship quality should assist with differentiating increasing, decreasing, and stable levels of commitment from breakup. Decreasing interactions with romantic partners is an indicator of declining relationship quality and also predicts breakup. Decreasing interaction is indicated by spending less time with the romantic partner, feeling separated from a romantic partner, avoiding each other – both in public and in private, such as ignoring phone calls and text messages – and making excuses for not going out together (Hess, 2003; Weisskirch & Delevi, 2012). Empirical support has shown that investing less time in a relationship is related to breakup (Le & Agnew, 2003; Rusbult et al., 2012). Yet, these findings do not describe how often and how varied experiences of decreased interaction differ between declining commitment and breakup.

Another indicator of declining relationship quality that is associated with breakup is relational uncertainty. Relational uncertainty is defined as “the degree of confidence people have in their perceptions of involvement within interpersonal relationships” (Knobloch, 2008, pg. 139). Uncertainty about relationships arises when individuals lack information about themselves and others (Knobloch, 2008). Feelings of uncertainty in a relationship typically occur when a relationship is low quality and can prompt breakup (Solomon & Theiss, 2008). For example, Arriaga (2001) found that couples who reported greater fluctuation in satisfaction in their relationships were more likely to breakup. However, few studies have examined varied experiences with relational uncertainty that could be used to differentiate why some couples breakup versus stay together. Therefore, for the current study we examine diverse experiences of alternative partners, decreased interactions, and relational uncertainty, as these variables represent different motivations to end a romantic relationship.

Using Decreased Interactions, Relational Uncertainty, and Alternative Partners to Identify and Differentiate Relationship Processes

The experience of decreased interactions, relational uncertainty, and alternative partners varies by frequency and intensity. For example, more frequent reports of decreased interactions with a romantic partner may predict breakup, whereas less frequent reports of decreased interactions may resemble declining commitment, but not breakup. More frequent adverse experiences in romantic relationships should negatively influence commitment, potentially prompting breakup. On the other hand, the degree that an individual experiences these hypothesized characteristics may also predict which couples remain intact versus breakup. For example, an individual who is uncertain about a significant other’s behavior may have different implications from an individual who is uncertain that a romantic relationship will succeed independent of frequency of these experiences. In other words, the severity of the experience may better predict changes in relationship processes – an individual who catches their partner having sexual intercourse with an alternative partner versus an individual who is mad at their partner for looking at an alternative partner during dinner may predict breakup despite the frequency of these experiences. The intensity and frequency of decreased interactions, relational uncertainty, and alternative partners are important variables to measure when predicting increases in commitment, decreases in commitment, and breakup. Thus, the first step for the current investigation is to examine the effects of frequency and intensity of the hypothesized characteristics to predict declining commitment from stability. Second, we examine how the frequency and intensity of these characteristics predict breakup as opposed to declining commitment to achieve the primary goal of this study.

Hypothesis 1: Compared to periods of stability, during periods of declining commitment individuals will report (a) fewer and less intense interaction with their partners, (b) more frequent and intense experiences of relational uncertainty, and (c) more frequent and intense references to alternative partners.

Hypothesis 2: Among participants experiencing declining commitment, individuals who breakup versus stay together report (a) fewer and less intense interactions with their partners, (b) more frequent and intense experiences of relational uncertainty, and (c) more frequent and intense references to alternative partners.

Method

Participants

Data for this investigation came from a larger study of the development of commitment among heterosexual dating couples that took place over a span of 9 months (Surra et al., 1999). During this time, participants completed up to nine face-to-face, monthly interviews in three phases. The first interview, Phase 1, lasted from 1 to 3 hours and involved each participant recalling retrospectively the development of their relationship from its beginning until the day of the interview. During Phase 2, for each of the subsequent 7 months, participants completed a short interview lasting 15 to 30 minutes to update their reports since the previous interview (also referred to as monthly updates). During the final Phase 3 interview, each participant gave a monthly update, completed other relationship measures, and again reported retrospectively on the development of their relationship from its beginning to the day of the interview. Research staff scheduled and conducted interviews separately for each partner either on campus or in participants’ homes, whichever was more convenient for participants. Although couples were recruited together, all interactions with participants occurred separately, meaning that some partners completed different numbers of interviews.

Sample

Participants were recruited by means of random digit dialing of approximately 36,000 homes in a large city in the Southwestern United States. Staff of a market research firm asked whoever answered the telephone if anyone in the household was dating someone of the opposite sex. If the answer was yes, the staff asked to speak to the dater, and proceeded through screening criteria (dating someone of the opposite sex, never-married, age between 19–35 years old, and expect to be in the area for 9 months; Surra et al., 1999), which yielded 861 eligible individuals. Of these, 27% agreed to participate and had partners who also agreed. These individuals were also asked for the name and address of their dating partner. Project staff then contacted both the original respondent and dating partner independently to ask about participation in the study. Of those eligible, 464 individuals and their partners (232 couples) agreed to participate and completed the first interview. Individuals who declined to participate stated that they or their partners were too busy, not interested, or were unable or unwilling to participate for the entire study.

Over the course of the study, a total of 18% of participants dropped out. Attrition analyses demonstrated that participants who dropped out did not differ significantly from participants who completed the study on any of the study variables. To be included in the current investigation, participants had to have completed at least two monthly updates from Phase 2 and 3, in which they described decreasing commitment to wed that lasted at least 1 month. We dropped 209 participants because they did not report declines in commitment to wed during the period of time covered by this study. Seventy-five participants were not included because one individual of a couple reported declining commitment and the other did not. These individuals were not statistically different from couples who did report declining commitment based on demographic variables. Ultimately, a total of 180 participants (90 couples) from the original sample had valid data and were included in this study. For the current study, participants on average completed 5.5 out of 8 possible interviews. The average age for female participants was 23.4 years (SD = 3.46) and 24.4 years for male participants (SD = 3.51). Seventy-five percent of participants identified themselves as white, with education levels that ranged from “high school dropout” to “a Master’s degree or more”, with the median education level “some college experience.” At the end of the study, the average relationship length was 25.75 months (SD = 26.57), but varied from 1.5 months to 156 months.

Procedures

During the Phase 1 interview, participants were asked to construct a graph from memory of changes in the chance to wed their partner over the course of the relationship. At each Phase 2 interview, respondents provided a monthly update of their relationship by first indicating whether they were dating the same partner. If so, they completed a graph of the chance of marriage from the date of the prior interview until the date of the current interview. For both phases, participants were shown a blank graph, which displayed chance of marriage from 0% to 100% on the vertical axis. The time in months was on the horizontal axis. The chance of marriage was defined with the following description: “There may have been times when you have thought, with different degrees of certainty about the possibility of marrying [partner’s name]. These thoughts have been based on your ideas about eventually marrying [partner’s name] and on what you think have been [partner’s name’s] thoughts about marrying you. Taking both of these things into consideration, I will graph how the chance of marrying [partner’s name] has changed over the time you have had a relationship.” Participants were told that if they were certain they would never marry their partner, the chance of marriage would be 0%, but if they were certain they would marry their partner the chance would be 100%.

For Phase 1, interviewers asked about and marked on the graph the chance of marriage today and at the beginning of the relationship. For Phase 2, interviewers asked about and marked on the graph the chance of marriage from today from the last interview. Next, participants were asked when they were first aware that the chance of marriage had changed from its initial value and the percentage at the time of the change. When the new value was marked, participants were asked about the shape of the line that should connect the two points (see Huston, Surra, Fitzgerald, & Cate, 1981, for a pictorial example of the graphing procedure). The period of time covered by this line constituted a turning point. After this line was drawn, the interviewer asked, “Tell me, in as specific terms as possible, what happened here from [date] to [date] that made the chance of marriage go [up/down] [__%]?” Participants were asked, “Is there anything else that happened…” until they said, “No.” This questioning continued in sequence until the graph reached the date of the interview. Participant’s responses were transcribed.

The Phase 3 interview took place approximately 9 months after the first interview. Participants completed two graphs. First, they graphed any change since their last Phase 2 interview. This report constituted the eighth monthly update. Next, participants constructed a retrospective graph of the chance of marriage from the beginning of their relationship until the day of the Phase 3 interview. Participants were paid $20 for each of the long interviews and $5 for each of the Phase 2 interviews. For this study, we use graph and transcripts from all of Phase 2 and the monthly update from Phase 3. Although the Phase 1 transcripts provide a view of how individuals portrayed their relationship development and maintenance, these descriptions were retrospective. While retrospective data are useful, they typically are less reliable than data collected at the time of the study and are prone to bias (Ash, 2009; Bradfield & Wells, 2005).

Distinguishing Declining Commitment from Stability

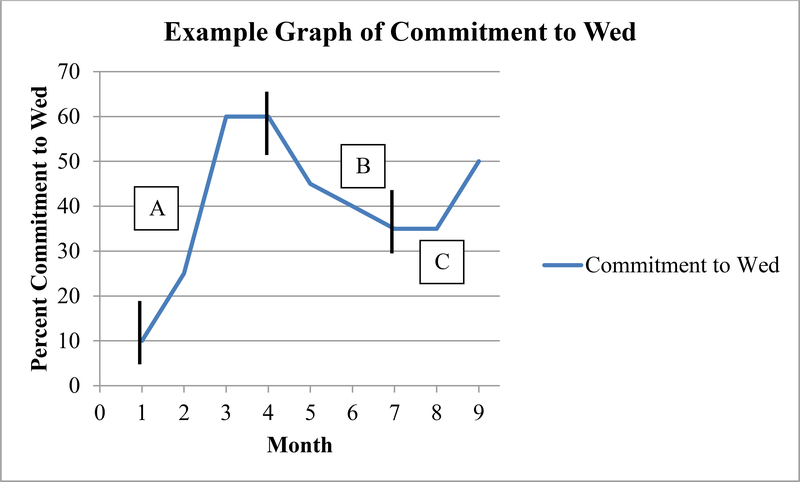

For the current investigation, we analyzed both the graphs and reasons for change in commitment to wed. Commitment to wed that declined at any rate for at least one month represented periods of declining commitment. This timeframe distinguishes declining commitment from fluctuations in commitment to wed, as fluctuations are commonly represented by daily changes in relationships (Arriaga, 2001; Ogolsky & Surra, 2014). For the current study, we used only the first instance of declining commitment to wed as this experience may have been the couple’s first experience with declining commitment. Participants who reported multiple instances of declining commitment were not significantly different from those who reported a single instance of declining commitment with respect to gender, age, race, education, and relationship length. Each graph was divided into sections representing stability, declining commitment, and post-declining commitment (see Figure 1). Instances of increases in or steady levels of commitment to wed before declining commitment were labeled stability. Some participants did not report a period of stability because at their first Phase 2 interview they reported a decline in commitment to wed (n = 48). These participants were not significantly different in terms of age, gender, education, race, and relationship length from participants reporting stability at their first Phase 2 interview, and therefore, were still included in all analyses. All subsequent declines in commitment to wed that lasted at least one month were labeled declining commitment. Any increases or steady levels of commitment to wed after declining commitment were labeled post-declining commitment, but were not used in this investigation.

Figure 1.

Portrayal of a hypothetical commitment to wed graph. Path A reflects stability with increasing and stable levels of commitment to wed. Path B reflects declining commitment with a pattern of declining commitment to wed that lasts over a month. Path C reflects the end of declining commitment with stability and increasing commitment to wed (post-declining commitment; not examined in this study).

Next, each participant’s reasons for changing commitment to wed were organized into two transcripts: a transcript representing stability (reasons that correspond to increasing and stable levels of commitment to wed until declining commitment, if participants reported stability at the first Phase 2 interview) and a transcript representing declining commitment (reasons that correspond to when commitment to wed decreased for at least one month) as reported in participants’ graphs. For example, Figure 1 portrays a hypothetical example of a graph of commitment to wed. For Path A, all of the reasons referencing increasing and stable levels of commitment to wed were combined in chronological order to create a “stability” transcript. Subsequently, participant’s reasons for declines in commitment to wed were combined into a “declining commitment” transcript (see Path B). Using the graphs and the transcripts provides a more precise, in-depth experience of declining commitment that we would have been unable to capture with standard measures of commitment (Ogolsky & Surra, 2014).

Coded Measures

After Phase 3 of the investigation in which the data originated, research assistants divided participant’s reasons for changing levels of commitment to wed into thought units. For example “Um, I was, just really missing my free time / and I felt like he and I were getting too close”, with each “/” designating different thought units (see Surra et al., 1999 for more details). For the current investigation, the first and second authors trained three undergraduate research assistants in the use of a coding manual describing how to rate different experiences of decreasing interaction, relational uncertainty, and alternative partners (available from first author) using randomly selected transcripts from Phase 1 of the original study until they reached an acceptable level of reliability (Cohen’s Kappa of at least .60). Research assistants read through each transcript and counted each time a thought unit fit one of the variables of interest (decreased interaction, relational uncertainty, alternative partners). Thought units that did not correspond with the variables of interest were not included. Based on the transcripts created for this study, approximately 10% of all thought units fit the variables of interest. The count of each code served as the measure of frequency. To measure the intensity of the thought unit, coders rated each thought unit found during the frequency task using the aforementioned coding manual. Intensity was defined as the degree to which the variable in question was expressed, and was rated on a scale of 1 (low) to 3 (high). Discrepancies among coders were discussed collectively until each research assistant agreed on a score. Research assistant’s codes were reliable based on Cohen’s Kappa for each code (range .63 – .83).

Decreased interaction.

A decrease in interaction was defined as spending less time with one’s partner, communicating less with one’s partner, or other descriptions of decreases in the amount of interaction, whether physical or emotional. An example of a thought unit coded as low intensity is, “I guess we weren’t talking on the phone as much,” and an example of high intensity is, “And we weren’t, um, speaking.”

Relational uncertainty.

This code was defined as doubts about the relationship or being unsure about the current state of the relationship. An example of low intensity is, “Eventually that’s how I started havin’ my doubts just cause the way she acted that night,” and an example of high intensity is, “I’m not sure he’s the one for me.”

Alternative partners.

This code was defined as an involvement with, anticipated involvement with, imagined involvement with, desired involvement with, or either partner’s attributions about or reactions to alternative dating partners. This code was separated into two subcategories: alternative partners – self (referencing alternative partners for the individual being interviewed) and alternative partner – partner (referring to alternative partners of the participant’s partner). Examples of the low intensity of alternative partners are, “I saw my old crush and…I was wonderin’ what it would be like if I was to date him instead” (self), and “I know that he…was thinking about her the entire time” (partner). High intensity examples include: “At this party, I had, actually made out with this other guy” (self), and “[She] had spent the night with somebody that I knew” (partner).

Breakup. Breakup status was measured by a single item asked at each monthly interview: “Which of the following stages best describes your relationship with [dating partner] right now?” One of the answer choices was “broken up.” If participants reported multiple breakups with the same partner across the study (n = 6), only the first breakup was used. When analyzing these two groups separately, the results were very similar; therefore, to increase the power of the study, participants reporting multiple breakups were included in all analyses. Also, all partners reporting a breakup agreed on the occurrence of a breakup, but they did not always agree on the timing of the breakup.

Analytic Strategy

The first hypothesis predicted that, compared to stability, during declining commitment, individuals will report more frequent and intense experiences of decreased interaction, relationship uncertainty, and alternative partners. For this hypothesis, we conducted analyses using hierarchical linear modeling (HLM; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). When testing for frequency, we analyzed separate models using decreased interaction, uncertainty, alternative partners – self, and alternative partners – partner as dependent variables. We included a time-varying dummy variable to distinguish declining commitment from stability. More specifically, we created a person-period dataset that designated each monthly interview as either stability, coded as a 0, or declining commitment, coded as a 1. We used a 3-level HLM model to analyze frequency of the hypothesized characteristics: stability versus declining commitment was used as the level-1, within-individual variable; gender was used as the level-2, within-couple variable; and relationship length was included as the level-3, between-couple variable. To test for differences in intensity, we used the variable indicating stability versus declining commitment and the variables for relational uncertainty, alternative partners – self, and alternative partners – partner as level-1 predictors. This approach makes decreased interaction the reference variable, which reflects the baseline level of intensity of decreased interactions for all participants. The coefficient for stability versus declining commitment quantifies the main effect of declining commitment on intensity across all codes. In addition, although HLM accounts for missing data using Full Maximum Likelihood, no data was missing at the between-person level for this dataset. For the current study, missing data occurred (at random) only when participants failed to complete a monthly update.

The second hypothesis predicted that higher frequency and intensity of decreased interactions, relationship uncertainty, and alternative partners during declining commitment will predict breakup versus staying together. To test this hypothesis, we conducted discrete-time survival analyses using binary logistic regressions, following the recommendations of Singer and Willett (2003). Discrete-time survival analysis assesses the probability that a randomly selected individual will experience an event; thus, the occurrence of breakup is the dependent variable. Two models were analyzed, using either frequency or intensity of the characteristics of declining commitment as independent variables.

Results

Describing Stability and Declining commitment

Descriptive statistics for the current study sample are displayed in Table 1. For the current sample (N = 180), women were significantly younger, on average, than men (23.4 years vs. 24.4 years; F(1, 179) = 3.95, p < .05). The experience of stability varied, as 48 participants (27%) began with declining commitment, 69 participants (38%) began with a steady level of commitment to wed, and 63 participants (35%) began with increasing levels of commitment to wed. A slight majority of the sample (n = 111) reported only one instance of declining commitment during the study. Individuals reporting multiple instances of declining commitment were not significantly different from participants reporting a single instance of declining commitment on demographic characteristics, frequency, or intensity of the hypothesized characteristics. Of the 90 couples included in the study, 27 (30%) reported a breakup. There were no gender differences regarding breakup, stability, or number of declining commitment experiences.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of couples experiencing declining commitment (N = 180).

| Males | Females | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 90 | 90 | |

| Age | 24.41 (3.51) | 23.38 (3.46) | |

| Race | |||

| White | 71 (78.9) | 64 (71.1) | |

| Not-white | 19 (21.1) | 26 (28.9) | |

| Religion | |||

| Protestant/Catholic | 29 (32.3) | 35 (38.8) | |

| Other religious affiliation | 39 (43.3) | 31 (34.5) | |

| Atheist/No religious beliefs | 22 (24.4) | 24 (26.7) | |

| Education | |||

| High school/GED or less | 20 (22.2) | 12 (13.3) | |

| Some college | 32 (35.6) | 39 (43.4) | |

| College degree | 35 (38.9) | 29 (32.2) | |

| Post college | 3 (3.3) | 10 (11.1) | |

| Breakup | |||

| Yes | 27 (30.0) | 27 (30.0) | |

| No | 63 (70.0) | 63 (70.0) | |

| Stability | |||

| Started with declining commitment | 19 (21.1) | 29 (32.2) | |

| Steady levels of commitment | 42 (46.7) | 27 (30.0) | |

| Increasing levels of commitment | 29 (32.2) | 34 (37.8) | |

| Number of Declining Commitment Experiences | |||

| Single instance of declining commitment | 58 (64.4) | 53 (58.9) | |

| Multiple periods of declining commitment | 32 (35.6) | 37 (41.1) | |

Note: Age is presented as averages with standard deviations in parentheses; all other information is presented as counts with column percentages in parentheses. Based on χ2 analysis, there were no differences on any variable across genders.

The average length of time of declining commitment was 44 days, but there was great variation (30 to 198 days). Over the period of declining commitment, commitment to wed declined an average of 16%, although, again, there was wide variation in the amount of decline, ranging from 4% to 100%. If experiencing breakup, couples reported that the breakup occurred during (30%) or after (70%) declining commitment. For couples who did not break up, most increased commitment to wed their partner (73%), indicating that after declining commitment, many couples may improve their relationship rather than breakup. The remaining participants who did not breakup either ended the study in declining commitment (15%) or with steady levels of commitment (12%).

Testing the Predictors of Declining Commitment versus Stability

Hypothesis 1 predicted that during declining commitment, participants will self-report fewer interactions with a romantic partner, increased references to uncertainty, and increased involvement with alternative partners relative to stability. The results for this hypothesis are presented in Table 2. The effect for stability versus declining commitment was significant for frequency of each characteristic. Although we predicted that declining commitment would be characterized by more intense statements of each characteristic compared to stability, we did not find support for this hypothesis.

Table 2.

Summary of the effect of frequency of each characteristic in predicting declining commitment and stability using hierarchical linear models (N = 180).

| Decreased Interaction | Relational Uncertainty | Alternative-Partner Self | Alternative Partner-Partner | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Effects | ||||

| Intercept | −.22 (.24) | −.12 (.23) | −.02 (.17) | −.01 (.13) |

| Stability versus declining commitment | .71 (.13)*** | .90 (.13)*** | .42 (.09)*** | .24 (.07)*** |

| Gender | .12 (.13) | .09 (.13) | .08 (.10) | .02 (.07) |

| Relationship length | .00 (.00) | .00 (.00) | .00 (.00) | .00 (.00) |

Note: Statistics are standardized beta coefficients and presented as B(SD).

p < .001

* p < .05

Hypotheses 2 predicted that for individuals experiencing declining commitment, increased frequency and greater intensity of the characteristics of declining commitment would predict breakup. Results are shown in Table 3, with the effects for frequency displayed on the top of the table and the effects for intensity displayed at the bottom. The coefficients for frequency of alternative partners – self and partner were significant, indicating that the likelihood of breakup increased significantly as the frequency of references to alternative partners increased. The effects for frequency of decreased interaction and relational uncertainty were not significant. The intensity of all four hypothesized characteristics significantly predicted breakup. The odds ratios indicate that an individual is 68% more likely to breakup if they reported more intense statements of relational uncertainty, 68% more likely for self-attention to alternative partners, 56% more likely for more intense statements of decreased interaction, and 55% more likely to breakup if they reported more intense partner’s attention to an alternative partner.

Table 3.

Summary of survival analyses predicting breakup (N = 180).

| Predictor | B | SE B | eB |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | |||

| Decreased Interaction | .09 | .11 | 1.09 |

| Relational Uncertainty | .20 | .10 | 1.22 |

| Alternative Partner – Self | .47** | .17 | 1.60 |

| Alternative Partner - Partner | .40* | .16 | 1.49 |

| Relationship Length | .01 | .01 | 1.01 |

| Constant | −3.74*** | ||

| χ2 | 12.37* | ||

| Intensity | |||

| Decreased Interaction | .44** | .16 | 1.56 |

| Relational Uncertainty | .52** | .17 | 1.68 |

| Alternative Partner – Self | .52** | .19 | 1.68 |

| Alternative Partner - Partner | .44* | .17 | 1.55 |

| Relationship Length | .00 | .01 | 1.00 |

| Constant | −4.57*** | ||

| χ2 | 24.16*** | ||

| % broken up at end of study | 30.0% | ||

Note: Model testing frequency is displayed at the top and the model testing intensity is at the bottom. Statistics represent standardized beta coefficients in predicting the likelihood of the event of breakup; eB = exponentiated B, the odds ratios.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001

Discussion

In this study, we advance knowledge about the processes of declining commitment and breakup in heterosexual romantic relationships in several ways. To our knowledge, this study is the first to demonstrate how declining commitment, defined in terms of declining commitment to wed that lasts at least one month, is a separate process from stability, defined in terms of increases in or steady levels of commitment to wed prior to declining commitment. Our findings show that relationships frequently experience a unique, but highly variable, period of declining commitment that is distinct from a period of stability, which is reflected in increased uncertainties, decreased interaction with the partner, and increased attention to alternative partners. Declining commitment is also distinct from breakup in that the predictors of declining commitment differ from those that predict whether relationships will end. The results of this study confirm that not all individuals who experience declining commitment will break up. Many couples experience decreasing commitment to marry their partners from which they recover, at least over the short-term, and that periods of declining commitment are common occurrences when dating. Such knowledge, while practiced over the short-run, may be good preparation for maintaining relationships over the long-run. Information from this study can assist couples during instances of declining commitment, particularly couples considering breakup based on less frequent, less intense experiences of decreasing interactions, relational uncertainty, and alternative partners.

Differentiating Stability and Declining Commitment

The results from the first hypothesis show that more references to decreases in interaction with partners, relational uncertainty, and alternative partners distinguish declining commitment from stability. Stability and declining commitment did not differ on the intensity of participants’ statements in these domains, however. These findings suggest that partners who are experiencing declining commitment are doing a more thorough analysis of reasons, perhaps even obsessive in some cases, for declines in commitment to wed, compared to periods of stability or growth in commitment to wed. Because we coded thought units, it was possible for participants to refer to and interpret certain events and experiences multiple times and in multiple ways within the same code, which may be reflected in excessively talking about negative relational experiences (Surra & Bohman, 1991; Surra, Curran, & Williams, 2009). In our study, rumination may be reflected in more frequent references to the characteristics of declining commitment.

It may also be possible that couples who experience declining commitment may ruminate more on negative relationship experiences. Experiences other than the ones tested in this study, such as conflicts, may cause declines in commitment that may spur more frequent thoughts of fewer interactions, relational uncertainty, or alternative partners. Future investigations would benefit from examining other potential sources of declining commitment to test for temporal order of the frequency and intensity of decreased interactions, relational uncertainty, and alternative partners. The contrast between periods of commitment to wed that are steady or increasing from periods when commitment to wed is decreasing may be unnerving for partners, as they try to make sense of, explain, and cope with declining commitment. This information is useful for both couples and practitioners to assist individuals when they describe negative relationship experiences. Individuals who experience declining commitment and still love their partner should focus on preventing rumination over negative relationship events.

Differentiating Declining Commitment and Breakup

The results from the second hypothesis distinguish the process of declining commitment from the event of breakup. Although several theorists have proposed models describing how relationships go through a period of declining commitment prior to breakup (Duck, 1981; Lee, 1984; Reed, 2007), empirical support for this notion has been weak. We found that the higher frequency of characteristics commonly associated with breakup in previous research as aligned with the investment model of commitment and relationship quality (Barber, 2006; Reed, 2007; Schoebi et al., 2012) predicts declining commitment, not breakup. The only case in which the frequency of statements predicts breaking up was alternative partners. Yet, the greater intensity of references to alternative partners, decreased interaction, and uncertainty increased the likelihood of breakup. In the context of premarital dating relationships, frequency of these characteristics predicts declining commitment, whereas intensity predicts breakup. In other words, more frequent experiences of decreased interactions, relational uncertainty, and alternative partners describes declining commitment that may not lead to breakup, whereas more intense experiences of these characteristics represent declining commitment that is predictive of breakup.

Frequency and intensity of alternative partners were both predictive of breakup. According to our results, the odds ratios for both measures suggest that thinking about alternative partners increases chance of breakup by 55% and higher. Individuals or their partners who desire or engage in external relationship experiences, such as flirting with alternative partners or finding someone else attractive may enable transitions from one relationship to another. In coding the transcripts, some participants went so far as to say that they planned to end the relationship as soon as they had another lined up. In this way, having alternative romances may be both a result of and a stimulus for breakup.

The findings further suggest that the intensity, or seriousness, of an experience involving decreased interaction, uncertainty, and alternative partners may prompt or be necessary for the movement from declining commitment to breakup. Relationships may be able to survive less serious elements associated with declining commitment, and may even recover from them. For example, not speaking with a partner and purposely avoiding them for extended periods of time may prompt breakup (Hess, 2003), but avoiding a partner for a shorter period of time is more likely a descriptive of declining commitment. An individual may have doubts about their partner’s behavior, but these doubts may not be strong enough to initiate breakup. Daters who have bouts of decreased interaction, uncertainty, or alternative partners that are of lower intensity may recover more easily from them, and they may be more comfortable with waning commitment to wed unless they receive strong and clear evidence that the relationship is over. In the case of alternative partners, individuals may be more likely to tolerate more frequent experiences of declining commitment that are lower intensity perhaps because these experiences are more difficult to interpret definitively. An individual whose partner is frequently caught gazing at alternative partners, a lower intensity experience, may be more tolerant of that behavior as long as the partner does not commit infidelity. The latter experience, which was coded as high intensity, contains clear information about where one stands with a partner and is much harder to deny or disregard. The ability to tolerate experiences of low intensity may predict steady levels of commitment or subsequent growth while highly interpretable experiences are more likely to lead to breakup. Understanding the differences between declining commitment and breakup, therefore, also has implications for relationship maintenance and conflict resolution.

From a prevention and intervention perspective, understanding the impact of decreased interactions, relational uncertainty, and alternative partners for declining commitment can provide professionals in the health and welfare services information to assist couples through difficult relationship experiences. First, consistent with the investment theory of commitment, clinicians should recommend that couples focus on decreasing attention to alternative partners in order to promote relationship development. If individuals are wary of their partner’s intentions with others, clinicians should recommend that couples work together to solve the problem to prevent more intense experiences with alternative partners, which should prevent breakup. Clinicians should also encourage couples to spend quality time with their partners when providing targeted intervention. For example, when dealing with distressed couples, clinicians should be aware of individuals who are insecure (Rhoades et al., 2011; Simon & Barrett, 2010), as they may be more likely to ruminate on whether or not their partner is ignoring them. Professionals in the health and welfare services should encourage communication with distressed couples regarding rumination and uncertainty to prevent more serious declines in couples’ commitment to wed. Given the results of this study, if clinicians or practitioners become aware of more intense instances of decreased interaction, relational uncertainty, or alternative partners, information from this study can provide a potential threshold that distinguishes when a couple may breakup during instances of declining commitment. Based on the findings of the current investigation, intervention approaches would vary depending on the frequency and intensity of decreased interactions, relational uncertainty, and alternative partners. When assisting couples in therapy, clinicians and healthcare professionals should help couples work together to understand the source of their problems and what to do to prevent these problems from occurring in the future (Kellas et al., 2008; Peterson, 2002). Distressed couples that experience intense bouts of the characteristics of declining commitment may be likely to seek help preparing for or coping with a potential breakup.

Limitations and Future Directions

Despite the uniqueness of this study, it has limitations. In an effort to limit priming of hypothesized characteristics, participants were not asked directly about either the occurrence or intensity of the characteristics of interaction, alternative partners, and uncertainty, which may have resulted in under reporting of these characteristics. Nevertheless, the lack of priming should have elicited the most important explanations for why commitment changed. Also, we measured an estimate of commitment to wed by means of chance of marriage. This measure is specific to the context of marriage while previous studies have measured global commitment. The use of more global measures of commitment, such as “Do you think your relationship will last over the long-run?” may produce different results. Also, individuals may view cohabitation or other relationship transitions as similar to marriage, but we did not focus on contexts outside of marriage. Thus, our findings of a distinct period of declining commitment may be specific to the context of romantic partners who have been asked to think about marriage. This measure also assumes that young adults want to get married, which may not have been true. Yet asking about commitment to wed could have prompted individuals to more seriously consider their commitment to their partner that other measures may not have captured. Future investigations should further validate the findings of this study in other relationship contexts. Another drawback to the current investigation was the focus on couples where both individuals reported declining commitment. In some relationships, only one individual may experience declining commitment whereas their partner may not. Future investigations are encouraged to examine the experience of declining commitment in these relationships to test for similarities and differences with couples who report declining commitment, which should provide a more nuanced depiction of declining commitment.

This study utilized censored data, both left-censored, where individuals may have experienced declining commitment prior to the study’s start, and right-censored, where the study may have ended before some relationships experienced declining commitment or a breakup. This limitation has the effect of decreasing the number of breakups that occurred and the number of individuals reporting declining commitment. A longer-term study design with more frequent measures of commitment to wed would be especially useful for studying post-declining commitment outcomes other than breakup. Also, by using survival analysis as our analytic approach, breakup was treated as an event rather than a process. However, the process of breakup in the relationship literature describes how declining commitment leads to the event of breakup (Connolly & McIsaac, 2009; Reed, 2007). This study provides evidence that the process of declining commitment is separate from the event of breakup.

From this study, we were able to define and distinguish declining commitment from stability and breakup based on facets of investment theory, relationship quality, and the breakup literature. Frequent perceptions of fewer interactions, more relational uncertainty and alternative partners signify that an individual is experiencing declining commitment. When these experiences are intense, the couple is more likely to break up. These findings provide empirical evidence for different processes in relationship development, maintenance, and dissolution. Information for this study can be used to help inform others about the effects of declining commitment that can be used for intervention and prevention of negative relationship experiences.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH47975).

Contributor Information

Michael R. Langlais, Family Studies, University of Nebraska – Kearney, Kearney, NE, USA.

Catherine A. Surra, Behavioral Sciences and Education, Penn State Harrisburg, Harrisburg, PA, USA.

Edward R. Anderson, Human Development and Family Sciences, University of Texas – Austin, Austin, TX, USA

Jennifer Priem, Department of Communication, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, NC, USA..

References

- Agnew CR, & VanderDrift LE (2015). Relationship maintenance and dissolution In Mikulincer M, Shaver PR, Simpson JA, Dovidio JF, Mikulincer M, Shaver PR, ... Dovidio JF (Eds.) , APA handbook of personality and social psychology, Volume 3: Interpersonal relations (pp. 581–604). Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; DOI: http://0-dx.doi.org.rosi.unk.edu/10.1037/14344-021. [Google Scholar]

- Arriaga XB (2001). The ups and downs of dating: Fluctuations in satisfaction in newly formed romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 754–765. DOI: http://0-dx.doi.org.rosi.unk.edu/10.1037/0022-3514.80.5.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arriaga XB, Reed JT, Goodfriend W, & Agnew CR (2006). Relationship perceptionsand persistence: Do fluctuations in perceived partner commitment undermine dating relationships?. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91, 1045–1065. DOI: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.6.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ash IK (2009). Surprise, memory, and retrospective judgment making: Testing cognitivereconstruction theories of the hindsight bias effect. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 35, 916–933. DOI: http://0-dx.doi.org.rosi.unk.edu/10.1037/a0015504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber BL (2006). To Have Loved and Lost...Adolescent Romantic Relationships and Rejection In Crouter AC, Booth A (Eds.) , Romance and sex in adolescence and emerging adulthood: Risks and opportunities (pp. 29–40). Mahwah, NJ US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Bradfield A, & Wells GL (2005). Not the same old hindsight bias: Outcome information distorts a broad range of retrospective judgments. Memory & Cognition, 33, 120–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly J, & McIsaac C (2009). Adolescents’ explanations for romantic dissolutions: A developmental perspective. Journal of Adolescence, 32, 1209–1223. DOI: http://0-dx.doi.org.rosi.unk.edu/10.3758/BF03195302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dailey RM, Rossetto KR, Pfiester A, & Surra CA (2009). A qualitative analysis of on again/off-again romantic relationships: “It’s up and down, all around”. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 26, 443–466. DOI: http://0-dx.doi.org.rosi.unk.edu/10.1177/0265407509351035. [Google Scholar]

- Duck SW (1981). Toward a research map for the study of relationship breakdown In Duck SW & Gilmour R (Eds.), Personal Relationships 3: Personal Relationships in Disorder (pp. 1–30). London England: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH (1980). Identity and the life cycle. New York, NY, US: W. W. Norton & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Hess JA (2003). Measuring distance in personal relationships: The Relationship Distance Index. Personal Relationships, 10, 197–215. DOI: http://0-dx.doi.org.rosi.unk.edu/10.1111/1475-6811.00046. [Google Scholar]

- Huston TL, Surra C, Fitzgerald N, & Cate R (1981). From courtship to marriage: Mate selection as an interpersonal process In Duck S & Gilmour R (Eds.), Personal relationships: Vol. 2. Developing personal relationships (pp. 53–88). London, England: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M (1999). Personal, moral, and structural commitment to relationships: Experiences of choice and constraint In Jones W & Adams J (Eds.), Handbook of interpersonal commitment and relationship stability (pp. 73–87). New York, NY: Plenum Press; DOI: http://0-dx.doi.org.rosi.unk.edu/10.1007/978-1-4615-4773-0_4. [Google Scholar]

- Kellas J, Bean D, Cunningham C, & Cheng K (2008). The ex-files: Trajectories, turning points, and adjustment in the development of post-dissolutional relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 25, 23–50. DOI: http://0-dx.doi.org.rosi.unk.edu/10.1177/0265407507086804. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley H (1983). Love and commitment In Kelley H, Berscheid E, Christensen A, Harvey J, Huston TL, Levinger G, … Peterson D (Eds.), Close relationships (pp. 265–314). New York, NY: Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Knobloch LK (2008). The content of relational uncertainty within marriage. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 25, 467–495. DOI: http://0-dx.doi.org.rosi.unk.edu/10.1177/0265407508090869. [Google Scholar]

- Le B, & Agnew CR (2003). Commitment and its theorized determinants: A meta-analysis of the investment model. Personal Relationships, 10, 37–57. DOI: http://0-dx.doi.org.rosi.unk.edu/10.1111/1475-6811.00035. [Google Scholar]

- Lee L (1984). Sequences in Separation: A framework for investigating endings of the personal (romantic) relationship. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 1, 49–73. DOI: http://0-dx.doi.org.rosi.unk.edu/10.1177/0265407584011004. [Google Scholar]

- Lichter DT, Turner RN, & Sassler S (2010). National estimates of the rise in serial cohabitation. Social Science Research, 39, 754–765. DOI: http://0-dx.doi.org.rosi.unk.edu/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD, Brown SL, & Payne KK (2014). Two decades of stability and change in age at first union formation. Journal Of Marriage And Family, 76, 247–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD, & Stykes B (2014). Twenty-five years of change in cohabitation in the U.S., 1987–2013. National Center for Family and Marriage Research: Family Profiles, FP-15–01, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Miller RS (2008). Attending to temptation: The operation (and perils) of attention to alternatives in close relationships In Forgas JP & Fitness J, (Eds.), Social relationships: Cognitive, affective, and motivational processes (pp. 321–337). [Google Scholar]

- Ogolsky BG, & Surra CA (2014). A comparison of concurrent and retrospective trajectories of commitment to wed. Personal Relationships, 21, 620–639. DOI: http://0-dx.doi.org.rosi.unk.edu/10.1111/pere.12054. [Google Scholar]

- Payne KK (2014). Marriage rate in the U.S., 2013. National Center for Family and Marriage Research: Family Profiles, FP-14–15, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson DR (2002). Conflict In Kelley HH, Berscheid E, Christensen A et al. (Eds.), Close relationships (pp. 265–314). Clinton Corners, NY: Percheron Press. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, & Bryk AS (2002) Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods (2nded.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Reed J (2007). Anatomy of a breakup: How and why do unmarried couples with children break up? In England P & Edin K (Eds.), Unmarried Couples with Children, (pp. 133–156). New York, US: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades GK, Kamp Dush CM, Atkins DC, Stanley SM, & Markman HJ (2011). Breaking up is hard to do: The impact of unmarried relationship dissolution on mental health and life satisfaction. Journal Of Family Psychology, 25, 366–374. DOI: http://0-dx.doi.org.rosi.unk.edu/10.1037/a0023627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult CE (1980). Commitment and satisfaction in romantic associations: A test of the investment model. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 16, 172–186. DOI: http://0-dx.doi.org.rosi.unk.edu/10.1016/0022-1031(80)90007-4. [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult CE (1983). A longitudinal test of the investment model: The development (and deterioration) of satisfaction and commitment in heterosexual involvements. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45, 101–117. DOI: http://0-dx.doi.org.rosi.unk.edu/10.1037/0022-3514.45.1.101. [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult CE, Agnew CR, & Arriaga XB (2012). The investment model of commitment processes In Van Lange PM, Kruglanski AW, Higgins E (Eds.) , Handbook of theories of social psychology (Vol 2) (pp. 218–231). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Salovey P, & Rodin J (1988). Coping with envy and jealousy. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 7, 15–33. [Google Scholar]

- Schoebi D, Karney BR, & Bradbury TN (2012). Stability and change in the first 10 years of marriage: Does commitment confer benefits beyond the effects of satisfaction?. Journal Of Personality And Social Psychology, 102, 729–742. DOI: 10.1037/a0026290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon RW, & Barrett AE (2010). Nonmarital romantic relationships and mental health in early adulthood: Does the association differ for women and men?. Journal Of Health And Social Behavior, 51, 168–182. DOI: http://0-dx.doi.org.rosi.unk.edu/10.1177/0022146510372343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, & Willett JB (2003). Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. New York, NY US: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Slotter EB, Gardner WL, & Finkel EJ (2010). Who am I without you? The influence of romantic breakup on the self-concept. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36, 147–160. DOI: http://0-dx.doi.org.rosi.unk.edu/10.1177/0146167209352250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon D, & Theiss JA (2008). A longitudinal test of the relational turbulence model of romantic relationship development. Personal Relationships, 15, 339–357. DOI: http://0-dx.doi.org.rosi.unk.edu/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2008.00202.x/ [Google Scholar]

- Sprecher S (1994). Two sides to the breakup of dating relationships. Personal Relationships, 1, 199–222. DOI: http://0-dx.doi.org.rosi.unk.edu/10.1111/j.1475-6811.1994.tb00062.x. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, & Markman HJ (1992). Assessing commitment in personal relationships. Journal Of Marriage And The Family, 54, 595–608. DOI: http://0-dx.doi.org.rosi.unk.edu/10.2307/353245. [Google Scholar]

- Surra CA, & Bohman T (1991). The development of close relationships: A cognitive perspective In Fletcher GO & Fincham FD, (Eds.), Cognition in close relationships (pp. 281–305). Hillsdale, NJ England: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Surra CA, Curran MA, & Williams K (2009). Effects of participation in a longitudinal study of dating. Personal Relationships, 16, 1–21. DOI: http://0-dx.doi.org.rosi.unk.edu/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2009.01207.x. [Google Scholar]

- Surra CA, & Hughes DK (1997). Commitment processes in accounts of the development of premarital relationships. Journal Of Marriage And The Family, 59, 5–21. DOI: http://0-dx.doi.org.rosi.unk.edu/10.2307/353658. [Google Scholar]

- Surra CA, Hughes DK, & Jacquet SE (1999). The development of commitment to marriage: A phenomenological approach In Adams JM, Jones WH (Eds.), Handbook of interpersonal commitment and relationship stability (pp. 125–148). Dordrecht Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; DOI: http://0-dx.doi.org.rosi.unk.edu/10.1007/978-1-4615-4773-0_7. [Google Scholar]

- Tach L, & Halpern-Meekin S (2009). How does premarital cohabitation affect trajectories of marital quality?. Journal Of Marriage And Family, 71, 298–317. DOI: http://0-dx.doi.org.rosi.unk.edu/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00600.x. [Google Scholar]

- VanderDrift LE, Agnew CR, & Wilson JE (2009). Nonmarital romantic relationship commitment and leave behavior: The mediating role of dissolution consideration. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35, 1220–1232. DOI: http://0-dx.doi.org.rosi.unk.edu/10.1177/0146167209337543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vangelisti AL ( 2006). Relationship dissolution: Antecedents, processes, and consequences In Noller P & Feeney JA ( Eds.), Close relationships: Functions, forms, and processes (pp. 353–374). New York: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weisskirch RS, & Delevi R (2012). Its ovr b/n u n me: Technology use, attachment styles, and gender roles in relationship dissolution. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, And Social Networking, 15, 486–490. DOI: http://0-dx.doi.org.rosi.unk.edu/10.1089/cyber.2012.0169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]