Abstract

This paper describes effects of the flexibility, length, and branching of side chains on the mechanical properties of low-bandgap semiconducting polymers. The backbones of the polymer chains comprise a diketopyrrolopyrrole (DPP) motif flanked by two furan rings and copolymerized by Stille polycondensation with thiophene (DPP2FT). The side chains of the DPP fall into three categories: linear alkyl (C8, C14, or C16), branched alkyl (ethylhexyl, EH, or hexyldecyl, HD), and linear oligo(ethylene oxide) (EO3, EO4, or EO5). Polymers bearing C8 and C14 side chains are obtained in low yields and thus not pursued. Thermal, mechanical, and electronic properties are plotted against the number of carbon and oxygen atoms in the side chain. We obtain consistent trends in the thermal and mechanical properties for branched alkyl and linear oligo(ethylene oxide) side chains. For example, the glass transition temperature (Tg) and elastic modulus decrease with increasing number of carbon and oxygen atoms, whereas the crack-onset strain increases. Among polymers with side chains of 16 carbon and oxygen atoms (C16, HD, and EO5), C16 exhibits the highest Tg and the greatest susceptibility to fracture. Hole mobility, as measured in thin-film transistors, appears to be a poor predictor of electronic performance for polymers blended with [60]PCBM in bulk heterojunction (BHJ) solar cells. For example, while EO3 and EO4 exhibit the lowest mobilities (< 10–2 cm2 V–1 s–1) in thin-film transistors, solar cells made using these materials performed the best (efficiency > 2.6%) in unoptimized devices. Conversely, C16 exhibits the highest mobility (≈ 0.2 cm2 V–1 s–1) but produces poor solar cells (efficiency < 0.01%). We attribute the lack of correlation between mobility and power conversion efficiency to unfavorable morphology in the BHJ solar cells. Given the desirable properties measured for EO3 and EO4, the use of flexible oligo(ethylene oxide) side chains is a successful strategy to impart mechanical deformability to organic solar cells, without sacrificing electronic performance.

TOC Entry.

This paper compares the electronic and mechanical properties of low-bandgap polymers with n-alkyl, branched alkyl, or oligo(ethylene oxide) side chains.

Introduction

The mechanical properties of π-conjugated polymers determine the amenability of devices based on these materials to roll-to-roll manufacturing and their stability in real-world environments.1–3 These properties are determined by chemical structure,4–9 molecular weight,10–14 and solid-state morphology.15 Conjugated polymers require side chains to solubilize the otherwise intractable conjugated core.16,17 Moreover, the structure and composition of these side chains influence the mechanical properties of solid polymeric films.5,18,19 This paper examines the role of the flexibility, length and branching of side chains on the thermomechanical and electronic properties of a collection of low-bandgap polymers in which the acceptor moiety is N-substituted diketopyrrolopyrrole (DPP) and the donor unit is thiophene, which is a class of materials described recently in an account by Janssen and coworkers, who pioneered the field.20 We compared linear alkyl, branched alkyl, and linear oligo(ethylene oxide) (EO) side chains and found that the crack-onset strain—a measure of extensibility—increases as the side chain is altered from linear alkyl to EO to branched alkyl (Scheme 1). These results have important implications for the design of semiconducting polymers for deformable electronics, including stretchable, ultra-flexible, and robust thin-film transistors and sensors21,22 for wearable23,24 and implantable25,26 health monitoring devices.

Scheme 1.

Chemical structure of PDPP2FT polymers with linear (n-) alkyl, branched alkyl, and oligo(ethylene oxide) side chains. The polymers bearing n-alkyl side chains with 8 and 14 carbon atoms were obtained in low yields and with low molecular weights and were thus not studied further.

Background

Semiconducting polymers require flexible, aliphatic side chains to be soluble in common organic solvents such as chloroform and dichlorobenzene. Side chains confer solubility by interrupting van der Waals interactions between main chains and by permitting greater entropic freedom of the polymer in solution.2 The size and attachment density of these side chains also has a profound effect on thermomechanical properties. For example, in the case of the regioregular poly(3-alkylthiophene)s (P3ATs), the elastic modulus decreases and the ductility increases with increasing length of the side chain.2,27 In a simple conception of a semiconducting polymer as comb-like, longer side chains reduce the energy needed for the polymer to deform by lowering the number of carbon–carbon bonds along the main chain that are aligned with (and bear) the applied load.28 Longer side chains also inhibit secondary interactions between main chains, increase the free volume, and thus lower the glass transition temperature (Tg).2,16,29,30 The relationship between Tg and the ambient temperature has a large effect on the mechanical properties: polymers above the Tg are rubbery and those below the Tg are glassy. The significance of the Tg is prominent in P3ATs: polymers with side chains of n ≥ 6 are rubbery and those with n < 6 are glassy at ambient temperature.18

The density of side chains and the ways in which they pack also influences the mechanical response. For example, polymers such as poly[2,5-bis(3-tetradecylthiophen-2-yl)thieno[3,2-b]thiophene] (PBTTT) exhibiting interdigitation of the side chains can be highly crystalline, and thus brittle.31 Interdigitation of the side chains is also observed in conjugated polymers comprising flexible, aliphatic spacers that interrupt conjugation along the backbone.6,32 Despite increased flexibility of the main chain, polymers with these so-called “conjugation-break spacers” may produce brittle films. This counterintuitive property has been attributed to the increased interdigitation of side chains (even for a low attachment density),33 which results in greater microstructural order, closer packing of main chains, and stiffening of the polymer film.34

Aside from the length and attachment density of side chains, other molecular aspects of these pendant groups (e.g., chemical structure and branching) have not yet been explored. While there is some evidence from a library of donor–acceptor polymers that branched side chains tend to produce ductile materials with low elastic moduli,5 the molecular weight and polydispersity of these polymers were not rigorously controlled. Furthermore, all previous studies on the mechanical properties of semiconducting polymers involved strictly alkyl side chains. The flexibility of linear EO chains suggests that polymers comprising such side chains should be deformable.35 To test this hypothesis, we compared DPP-based polymers with side chains of three different kinds: namely, linear alkyl, branched alkyl, and linear EO.

Experimental Methods

Materials.

[6,6]-Phenyl C61 butyric acid methyl ester ([60]PCBM) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich with >99% purity. (Tridecafluoro-1,1,2,2-tetrahydrooctyl)-1-trichlorosilane (FOTS) and octadecyltrichlorosilane (OTS) were obtained from Gelest. Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly(styrene sulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS, Clevios PH 1000) was purchased from Heraeus. DMSO was purchased from BDH. Chloroform, ortho-dichlorobenzene (oDCB), dimethylformamide (DMF), and tetrahydrofuran (THF) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. All other reagents were used as received unless specified otherwise. Unless otherwise noted, all reactions were carried out under nitrogen with standard Schlenk techniques.

Characterization of the polymers.

All compounds were characterized by 1H NMR (300 MHz, Bruker) and 13C NMR (500 MHz, Jeol) using CDCl3 as the solvent. The residual chloroform peak at 7.28 ppm was used to calibrate the chemical shifts for 1H NMR. Gel-permeation chromatography (GPC) was carried out in chloroform using an Agilent 1260 separation module equipped with a 1260 refractive index detector and a 1260 photodiode array detector. Molecular weights were calculated relative to linear polystyrene standards. Atomic force micrographs were obtained using a Veeco scanning probe microscope (SPM) in tapping mode, and the data were analyzed with NanoScope Analysis v1.40 software (Bruker Corp.). Ultraviolet-visible (UV-vis) absorption spectra were obtained for polymers in chloroform and in the solid state (as cast from chloroform at 10 mg mL–1) using a Perkin Elmer Lambda 1050 UV-vis-NIR spectrometer.

Synthesis of monomers.

Synthesis of the series PDPP2FT-EOx was carried out using the following procedure, shown below for the case of PDPP2FT-EO3, beginning with the monomers. The syntheses of PDPP2FT-EO4 and PDPP2FT-EO5 were carried out in the same way and described in detail in the Supporting Information. Synthesis of the monomer, DPP2F-EO3, was carried out in three steps (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Synthetic pathway for the monomers with oligo(ethylene oxide) (EO) side chains.

3,6-di(furan-2-yl)-2,5-dihydropyrrolo[3,4-c]pyrrole-1,4-dione (2):

A 500 mL three-neck round-bottom flask connected to a condenser and dry nitrogen flow was charged with a stir bar and tert-amyl alcohol (140 mL), furan-2-carbonitrile (1) (6.24 g, 68.8 mmol), and sodium pentoxide 1.4 M in THF (49 mL, 60 mmol). The temperature was progressively raised to 120 °C. Diethyl succinate (4.18 g, 24.0 mmol) was added dropwise over a period of 10 min. The reaction mixture turned dark orange-red, and the resulting mixture was stirred for 2 h. MeOH (300 mL) and acetic acid were added to the hot mixture, and the resulting mixture was stirred for 2 h with reflux. The reaction mixture was then cooled to room temperature, and the resulting compound was filtered over a Buchner funnel for collection and dried under vacuum (3.7 g, 58% yield). Compound 2 was used without further purification.

3,6-di(furan-2-yl)-2,5-bis(2-(2-(2-methoxyethoxy)ethoxy)ethyl)-2,5-dihydropyrrolo[3,4-c]pyrrole-1,4-dione (3-EO3):

EO3-OTs (generalized as ROTs in Scheme 2) was synthesized according to a previously reported synthesis.36 Compound 2 (3.32 g, 12.4 mmol), EO3-OTs (14.96 g, 47.0 mmol), tetra-n-butylammonium bromide (0.40 g, 1.24 mmol) and 120 mL of dry DMF were added to a 250 mL single-neck round–bottom flask, equipped with stir-bar and placed under nitrogen atmosphere. The mixture was heated to 120 °C and stirred for 45 h. The reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature. DMF was removed under vacuum distillation, and distilled water (200 mL) was added. The product was extracted with chloroform, then washed with brine, and dried over MgSO4, and red solid was purified by silica gel chromatography eluting with CHCl3 / acetone (9:1 to 8:2). 2.12 g of 3-EO3 were isolated (31% yield). (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) = 8.28 (d, J = 3.5 Hz, 2 H), 7.66 (d, J = 1.1 Hz, 2 H), 6.69 (dd, J = 1.8 Hz, 3.7 Hz, 2 H), 4.37 (t, J = 6.3 Hz, 4 H), 3.74 (t, J = 6.3 Hz, 4 H), 3.70 – 3.40 (m, 16 H), 3.35 (s, 6 H). The 1H NMR characterization is consistent with previous reports of this compound.37

3,6-bis(5-bromofuran-2-yl)-2,5-bis(2-(2-(2-methoxyethoxy)ethoxy)ethyl)-2,5-dihydropyrrolo[3,4-c]pyrrole-1,4-dione (4-EO3):

Compound 3-EO3 (2.11 g, 3.77 mmol) and 170 mL of CHCl3 was charged in a 250 mL single-neck round–bottom flask, equipped with stir-bar and placed under nitrogen atmosphere. The mixture was cooled to 0 °C and stirred while N-bromosuccinimide (NBS, 1.41 g, 7.92 mmol) was added in small portions. The mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature and stirred for 67 h following complete addition of NBS. The organic phase was extracted with CHCl3 and washed with water. The CHCl3 was evaporated, and the resulting tacky, dark red solid was purified by silica gel chromatography eluting with CHCl3 / acetone (9:1 to 8:2). 2.35 g of 4-EO3 were isolated (87% yield). (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) = 8.23 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 2 H), 6.63 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 2 H), 4.32 (t, J = 6.1 Hz, 4 H), 3.75 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 4 H), 3.70 – 3.40 (m, 16 H), 3.35 (s, 6 H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ (ppm) = 160.52, 146.20, 132.69, 126.49, 122.15, 115.56, 106.43, 71.98, 70.71, 70.62, 70.57, 69.52, 59.10, 41.69. HR-MS: m/z calc’d for C28H35Br2N2O10 [M+H]+ 717.0647 found 717.0653.

The synthesis of the EO4 and EO5 monomers followed similar procedures and is reported in the Supporting Information.

Synthesis of PDPP2FT polymers.

The three known polymers, PDPP2FT-EH, PDPP2FT-HD, and PDPP2FT-C16, were synthesized according to previously reported procedures.29 The polymerization of PDPP2FT-EO3 proceeded as follows (Scheme 3): 4-EO3 (215 mg, 0.300 mmol), 2,5-bis(trimethylstannyl)-thiophene (5) (117 mg, 0.285 mmol), Pd2(dba)3 (2.7 mol %) and P(o-tolyl)3 (10.7 mol %) were charged within a 25 mL 3-necked flask, cycled with nitrogen and subsequently dissolved in 6 mL of degassed chlorobenzene. The mixture was stirred for 20 h at 110 °C. The reaction mixture was allowed to cool to 25 °C, 5 mL of CHCl3 was added, and precipitated into methanol (200 mL). The precipitate was purified via Soxhlet extraction for 3 h with methanol and 3 h with hexanes, followed by collection in chloroform. The polymer 6-EO3 (PDPP2FT-EO3) was obtained as a dark solid (170 mg). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm) = 8.37 (bs, 2H), 7.28–6.74 (m, 4H), 4.38–3.33 (m, 30H). The polymerization reactions for PDPP2FT-EO4 (6-EO4) and PDPP2FT-EO5 (6-EO5) followed similar conditions as described in the Supporting Information. (Since the polymers all have a common backbone, PDPP2FT, they are referred to in the rest of the paper by their side chains using the following simplified forms: EH, HD, C16, EO3, EO4, EO5.) GPC analysis for all polymers is available in Table S1, and their GPC traces can be found in the Supporting Information.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of PDPP2FT-EOx polymers.

Preparation of glass substrates.

Glass slides were cut into squares 2.5 cm per side with a diamond-tipped scribe. The slides were then successively washed in Alconox solution (2 mg mL–1), deionized water, acetone, and isopropyl alcohol (IPA) in an ultrasonic bath for 10 min each and dried with compressed air. The glass slides were then plasma treated (~30 W) for 3 min at a pressure of 200 mTorr under ambient air to remove any residual organic material and activate the surface. The surfaces were then passivated by treating the slides with ~100 μL of FOTS and placing them under static vacuum for 3 h. Finally, the glass slides were thoroughly rinsed with IPA to remove excess FOTS. The finished surface had a water contact angle of approximately 110°.

Mechanical buckling.

Sylgard 184 polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) was prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions at a ratio of 10:1 (base:crosslinker) and cured at room temperature for 36 to 48 h prior to use in mechanical testing. After curing, the PDMS was cut into rectangular strips (l = 10 cm, w = 1 cm, h = 0.3 cm) for use in buckling experiments. The PDMS strip was pre-strained to 2–4% on a linear actuator and fixed to a glass slide. Thin films of each polymer were prepared at three different thicknesses and transferred to PDMS substrates. The applied strain was released, and the resulting wrinkles (due to a mechanical buckling instability) were analyzed under a Leica DM2700M microscope. The thickness of the films was measured using a Veeco Dektak stylus profilometer, and the elastic modulus of PDMS was measured using an Instron pull tester. The Poisson ratio of PDMS and the polymer films were estimated to be 0.5 and 0.35, respectively.38 This general procedure and calculation of the elastic moduli of the polymers are reported in detail elsewhere.12

Crack-onset strain.

Measurements of the crack-onset strain were performed by transferring polymer films to pristine strips of PDMS, which were then elongated in increments of 1% using a linear actuator. The films were inspected under the microscope and progressively elongated until cracks or pinholes appeared. In brittle samples, the crack-onset strain was marked at the formation of long, slender cracks. In ductile samples, the crack-onset strain was marked either on the appearance of new pinholes—which often resemble diamond-shaped microvoids—or on the enlargement of preexisting pinholes.12

Fabrication of organic field-effect transistors (OFETs).

Highly doped (0.001–0.005 Ω cm) n-type Si wafers with 300 nm of oxide were functionalized with a crystalline OTS monolayer using a previously reported technique.39 Polymers were dissolved in chloroform (10 mg mL–1) and allowed to stir overnight. Films were then spin coated in air at 1500 rpm for 2 min, annealed at 100 °C for 1 h in a nitrogen glovebox, and tested using a Keithley 4200 parameter analyzer in a nitrogen glovebox.

Fabrication of organic photovoltaic (OPV) devices.

We fabricated photovoltaic devices using [60]PCBM as the electron acceptor. All polymers were mixed in a 1:2 ratio with [60]PCBM (polymer:PCBM) at a concentration of 10 mg mL−1 in a solution of 1:4 oDCB:CHCl3. The solutions were stirred overnight and filtered with a 1 µm syringe filter prior to spin coating. The films were spin coated at a rate of 1000 rpm (500 rpm s−1 ramp) for 120 s followed by 30 s at a speed of 2000 rpm (1000 rpm s−1 ramp) with no thermal treatment. We deposited a layer of PEDOT:PSS containing 7% DMSO and 0.1% Zonyl as the transparent electrode at a rate of 500 rpm (250 rpm s−1 ramp) for 120 s followed by 30 s at a speed of 2000 rpm (1000 rpm s−1 ramp). The PEDOT:PSS films were annealed on a hot plate at 150 °C for 30 min. We selected eutectic gallium-indium (EGaIn) as the top contact for all solar cell measurements.

Results and discussion

Synthesis of polymers.

We chose, as a donor–acceptor system, a polymer based on the N-substituted DPP unit flanked by two furan rings and copolymerized with thiophene (PDPP2FT). Polymers of this type, first described by the Fréchet group, exhibit increased solubility compared to those in which the furan rings are substituted with thiophene rings.40 The DPP2FT unit bearing each of 8 different side chains is condensed with a thiophene ring in a Stille polymerization to yield polymers for testing (Scheme 1). Polymers bearing linear side chains with shorter lengths (i.e., C8 and C14) were synthesized in low yields and with low molecular weights because of the poor solubility of the starting materials and products (Table 1). These materials were thus not explored further. With C16 as the side chain, however, the polymer was produced in high yield and with high molecular weight. Two polymers bearing branched side chains—ethylhexyl (EH) and hexyldecyl (HD)—were also produced, both of which exhibited good solubility and high-quality thin films by spin coating. In addition to these polymers comprising hydrocarbon side chains, we prepared three examples of polymers with oligo(ethylene oxide) side chains of 3, 4, and 5 repeat units (EO3, EO4, and EO5). These six materials allow for direct comparison of the effects of the structure of the side chain. For example, the progression from EO3 to EO4 to EO5 allows measurement of the evolution in properties as the side chain is lengthened by one EO unit at a time. Comparison of EO5, HD, and C16, on the other hand, allows comparison of properties between materials with an equal number of carbon and oxygen atoms (i.e., 16) in the side chain.

Table 1.

Molecular Characterization of DPP-Based Polymers with Various Side Chains

| Entry | Number of C and O atoms in side chain |

Yield (%) |

Mn

a (kg mol–1) |

Mw

a (kg mol–1) |

PDI a | λmax (nm)b |

Egopt (eV) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solution | Film | |||||||

| EO3 | 10 | 65 | 14.6 | 52.8 | 3.6 | 812 | 830 | 1.35 |

| EO4 | 13 | 60 (70) | 17.1 (21.8) | 44.8 (151.6) | 2.6 (7.0) | 812 | 832 | 1.34 |

| EO5 | 16 | 86 | 23.8 | 116.8 | 4.9 | 813 | 835 | 1.33 |

| EH | 8 | 59 (57) | 19.6 (33.8) | 63.7 (138.8) | 3.3 (4.1) | 812 | 797 | 1.41 |

| HD | 16 | 74 | 29.2 | 101.4 | 3.5 | 812 | 807 | 1.41 |

| C8 | 8 | 10 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| C14 | 14 | 11 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| C16 | 16 | 74 (74) | 64.9 (57.2) | 268.9 (331.6) | 4.1 (5.6) | 813 | 809 | 1.37 |

Determined by GPC relative to polystyrene standards. (The numbers in parentheses indicate the molecular weight of the polymer used in the characterization of electronic properties).

Determined by UV-vis. (ND: No data acquired).

Glass transition temperature.

The Tg reflects the thermal motility of polymer chains in a solid film, and its value has a strong influence on mechanical properties.2 We measured the Tg using an approach previously developed by our group that is based on the onset of aggregation detected by UV-vis spectroscopy.41 The trend from EO3 to EO5 shows a monotonic decrease in Tg from 123 °C to 94 °C (Figure 1a). The inverse correlation between the length of the side chain and Tg has previously been observed in P3ATs.18 The Tgs, however, are much greater for polymers with backbones comprising the DPP2FT unit than those comprising only thiophene rings, which afford greater flexibility to the chains. In the series consisting of 16 atoms in the side chain, EO5 has the lowest Tg, followed by HD and C16. This trend suggests that increased flexibility of a linear side chain has a greater effect in depressing the Tg than does branching.

Figure 1.

Thermal and mechanical properties of the synthesized polymers. (a) Tg, (b) elastic modulus, and (c) crack-onset strain as functions of the number of carbon and oxygen atoms in the side chain. (c) Optical micrographs of the cracking behavior on PDMS at 0% (pristine), 20%, and 50% applied strain.

Mechanical properties.

We expected the materials with low Tg to also exhibit low elastic moduli and high extensibilities. Elastic moduli were measured using the buckling-based methodology (Figure 1b); again, the trend for EO3, EO4, and EO5 shows that the longer the side chain, the lower the modulus. The modulus of EH is exceptionally high (~3 GPa), while that of HD is nearly an order of magnitude lower. The trend among the samples having 16 atoms in the side chain does not exactly match the one found for the Tg: while EO5 has the lowest modulus, the modulus of HD is slightly higher than that of C16, though the values are similar.

The ductility or extensibility, as measured by the crack-onset strain (Figure 1c), is greatest for HD, although this value is within the uncertainty of the extensibility of EO5. This comparison is also complicated by the fact that the crack-onset strain strongly depends on the quality of the film, as thin regions and defects are sites at which stress localizes and where fracture initiates and propagates.12 The crack densities at 0%, 20%, and 50% applied strain for each polymer were imaged using optical microscopy (Figure 1d). The high ductility of HD and EO5 is consistent with their low crack densities at 50% applied strain. Interestingly, EO4 has a crack-onset strain nearly equal to that of EO5, though EO4 has a much greater crack density at 50% applied strain. This observation is consistent with greater energy dissipation in the material with increasing length of the side chain.

When analyzing the effects of molecular structure of a polymeric material on its mechanical properties, it is critical to separate these effects from those of unequal molecular weights. To mitigate the effects of unequal molecular weight, we attempted to obtain polymers in as narrow a range as possible. As shown in Table 1, the range of Mn was 14.6 to 33.8 kg mol–1 for all polymers except for the outlier, C16 (65.9 kg mol–1), though the polydispersities ranged from 2.6 to 4.9. While this variability was potentially concerning, some of our observations suggest that the measured mechanical properties were more a consequence of molecular structure than of molecular weight. For example, when holding molecular structure constant, the effect of increasing molecular weight is usually to increase the ductility. For the set of compounds we tested, however, C16 had a much higher molecular weight than the other samples, yet it was also the most brittle. (Given the insolubility of C8 and C14, however, we cannot discount the possibility that C16 formed aggregates in solution and thus gave an artificially high molecular weight by GPC.) Additionally, EO5 had an exceptionally high weight-average molecular weight (Mw = 116.8 kg mol–1), yet it had near the same crack-onset strain as EO4 (Mw = 44.8 kg mol–1). While we recognize the large effect of molecular weight on the mechanical properties of polymers, our measurements suggest that these effects were masked by even larger effects due to the length, branching, and flexibility of the side chains.

Optical properties.

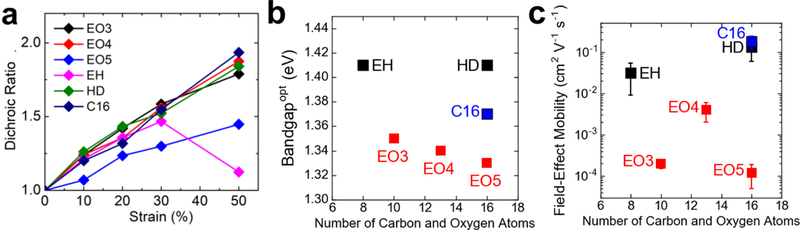

Stretching the conjugated polymers aligns the chains, which results in absorption that exhibits anisotropic absorption of polarized light42 (i.e., absorption is greater when incident light is polarized parallel to the strained axis). This anisotropy—quantified by the dichroic ratio—is a measure of the extent to which mechanical stress aligns main chains. In Figure 2a, the dichroic ratio is plotted as a function of the applied strain for each material; except for EH, the dichroic ratio is a monotonically increasing function of strain. The dichroic ratio of EH increases from 0% to 30% strain, but then decreases above 30%. This behavior could be the result of chain alignment up to moderate (30%) strain, followed by a return to a more isotropic state as the film fractures and the intact regions rebound elastically. Figure 2a also reveals slow increase in the dichroic ratio of EO5 with strain compared to those of EO3 and EO4. We hypothesize that greater free volume and more degrees of freedom in EO5 enable better dissipation of mechanical stress (e.g., through stretching and rotation of bonds) with less alignment of main chains.

Figure 2.

Optical and electronic properties of the synthesized polymers. (a) Evolution in dichroic ratio of each material as a function of applied strain. (b) Optical bandgap and (c) hole mobility as functions of the number of carbon and oxygen atoms in the side chain.

Optical bandgap.

We measured the optical bandgap of our polymers and plotted it as a function of the number of carbon and oxygen atoms in the side chain (Figure 2b). Polymers with EO side chains have the smallest bandgaps, while polymers with branched side chains have the largest bandgaps. Previous work on EO-substituted polythiophenes shows a similar narrowing in bandgap compared to their alkyl-substituted counterparts.43 Narrowing in the bandgap of EO-substituted polymers is attributed to long conjugation lengths that stabilize planar conformations by facilitating interaction between the EO side chains.44 Based on Figure 2b, this phenomenon appears to also hold for the low-bandgap polymers, the bandgap of which decreases with increasing length of the EO side chain. The PDPP2FT-based polymers with branched side chains, on the other hand, have larger bandgaps than those with linear side chains, which suggests greater steric hindrance between branched side chains that reduces the conjugation length by destabilizing planarity.45 The branched polymers EH and HD have nearly equal bandgaps, which suggests that lengthening of linear side chains does not significantly contribute to steric hindrance. Roncali et al. suggest that steric hindrance (in polythiophenes) is not affected by the length of branched side chains, but rather is influenced by the position of the branch point relative to the main chain.45 In future studies, altering the branch point of these side chains may be a viable approach to tune optoelectronic properties while retaining mechanical robustness.

Since low bandgaps and high conjugation lengths correspond to enhanced intramolecular charge transport,46 our results regarding conjugation along the backbone (Figure 2b) may account for the high photovoltaic performance of polymers with EO side chains in BHJ solar cells. Indeed, extensive conjugation allows charges to more effectively reach the donor-acceptor interface for charge separation, which explains the high photovoltaic performance of polymers with EO side chains despite their poor field-effect mobilities (Figure 2c), as field-effect mobility is often limited by intermolecular charge transport.47

Charge-carrier mobility.

We fabricated bottom-gate top-contact field-effect transistors to quantify charge-carrier mobility. Hole mobility was plotted in Figure 2c as a function of the number of carbon and oxygen atoms in the side chain. The materials with the highest mobilities were C16 and HD; EO5—the most deformable polymer—had the lowest mobility. We attribute the poor field-effect mobility of the polymers with EO side chains to poor molecular packing at the interface between these chains and OTS-treated surfaces. It is also possible that the increased polarity of these side chains promotes charge trapping by attracting water molecules or ionic impurities.48 Our results indicate that the length of side chains, compared to their chemical structure and branching, has a weak effect on hole mobility. This observation suggests that modification of the chemical structure, rather than the size, of side chains is a possible path to improve the mechanical properties of low-bandgap polymers.

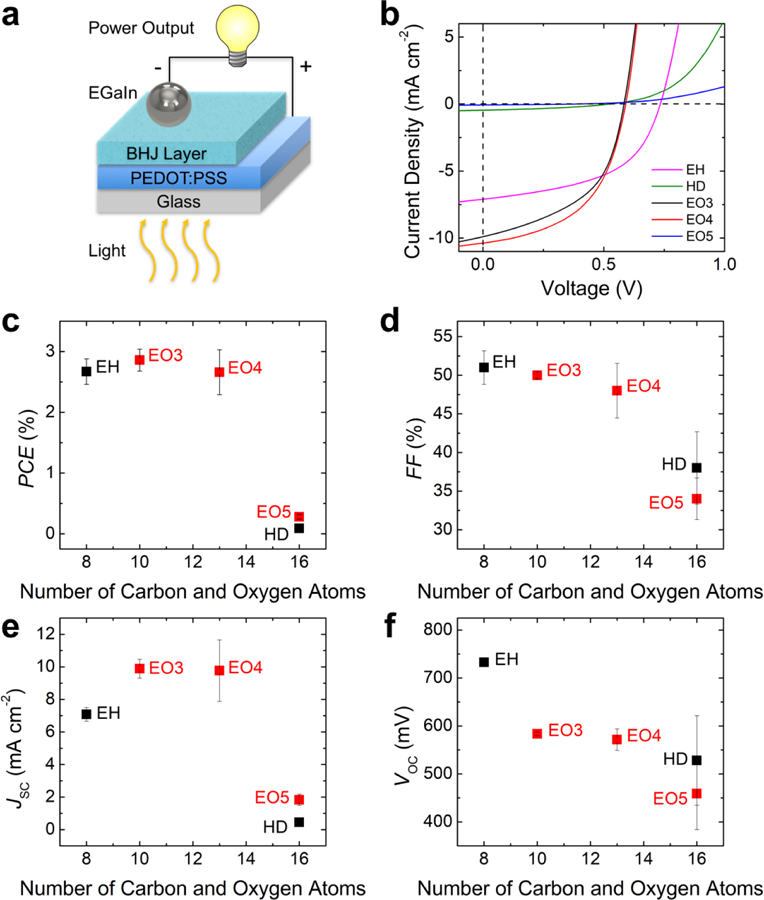

Photovoltaic performance.

Given the importance of mechanical reliability in both the (roll-to-roll) fabrication and use of polymer-based organic solar cells,49–51 we sought to measure the photovoltaic performance of our materials when blended in a 1:2 ratio by weight with [60]PCBM. The architecture of these devices is shown in Figure 3a. PEDOT:PSS was selected as the transparent anode and eutectic gallium-indium (EGaIn) as the cathode. The choice of electrodes was based on considerations of mechanical deformability, ease of fabrication, and consistency between different materials, as opposed to achieving the best possible photovoltaic performance. The current–voltage (J–V) properties of the polymers are presented in Figure 3b (best-performing cells), with averages for the figures of merit (power conversion efficiency (PCE), fill factor (FF), short-circuit current density (JSC), and open-circuit voltage (VOC)) plotted in Figure 3c–f and tabulated in Table 2. Three of the six polymers (HD, EO5, and C16) made poor solar cells with PCE values less than 0.3%. The other three polymers made functional solar cells with similar PCEs (>2.5%). Although HD has the highest field-effect mobility, it produced poor solar cells, possibly due to disrupted packing caused by the long, branched side chains and an unfavorable BHJ morphology when mixed with [60]PCBM.

Figure 3.

Photovoltaic properties of the synthesized polymers. (a) Architecture of the polymer-based organic solar cells. (b) Plots of current density vs. voltage for devices made from each of the six polymers. (c-f) Plots of PCE, FF, Jsc, and Voc, averaged over three devices of each type.

Table 2.

Photovoltaic Properties of DPP-Based Polymers with Various Side Chains

| Material | Jsc (mA cm−2) | Voc (mV) | FF (%) | PCE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EH | 7.08 ± 0.42 | 733 ± 02 | 51.4 ± 2.2 | 2.67 ± 0.21 |

| HD | 0.45 ± 0.07 | 528 ± 93 | 38.3 ± 4.7 | 0.09 ± 0.03 |

| EO3 | 9.89 ± 0.58 | 583 ± 03 | 49.6 ± 0.5 | 2.86 ± 0.18 |

| EO4 | 9.77 ± 1.89 | 571 ± 22 | 48.2 ± 3.5 | 2.66 ± 0.37 |

| EO5 | 1.83 ± 0.35 | 459 ± 75 | 34.0 ± 2.7 | 0.28 ± 0.04 |

Conclusions

This paper demonstrated the effects of the length, branching, and chemical structure of side chains on the thermal, mechanical, and optoelectronic properties of a series of polymers with a common donor–acceptor backbone. While the role of side chains has been extensively studied on model systems such as polythiophenes, the influence of side chains on the mechanical behavior of donor–acceptor materials has been underexplored. We found that linear side chains with high flexibility, such as oligo(ethylene oxide), are a viable pathway toward organic semiconductors with high deformability without sacrificing electronic performance. In particular, EO4 appeared to exhibit the best of all worlds in terms of its favorable field-effect mobility, low modulus, high extensibility, and good performance in a solar cell. These findings suggest a molecular design strategy toward fabricating mechanically compliant semiconducting polymers for organic solar cells as well as wearable and biointegrated devices.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported primarily by the NIH Director’s New Innovator Award under grant 1DP2EB022358–02 and by the JSR Corporation. D. R. and J. R. were supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program under grant number DGE-1144086.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

References

- 1.Jørgensen M, Norrman K, Gevorgyan SA, Tromholt T, Andreasen B and Krebs FC, Adv. Mater, 2012, 24, 580–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Root SE, Savagatrup S, Printz AD, Rodriquez D and Lipomi DJ, Chem. Rev, 2017, 117, 6467–6499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fukuda K, Takeda Y, Yoshimura Y, Shiwaku R, Tran LT, Sekine T, Mizukami M, Kumaki D and Tokito S, Nat. Commun, 2014, 5, 4147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lipomi DJ, Chong H, Vosgueritchian M, Mei J and Bao Z, Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells, 2012, 107, 355–365. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bérenger R, Savagatrup S, De Los Santos NV, Hagemann O, Carlé JE, Helgesen M, Livi F, Bundgaard E, Søndergaard RR, Krebs FC and Lipomi DJ, Chem. Mater, 2016, 28, 2363–2373. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Savagatrup S, Zhao X, Chan E, Mei J and Lipomi DJ, Macromol. Rapid Commun, 2016, 37, 1623–1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu HC, Hung CC, Hong CW, Sun HS, Wang JT, Yamashita G, Higashihara T and Chen WC, Macromolecules, 2016, 49, 8540–8548. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang GJN, Shaw L, Xu J, Kurosawa T, Schroeder BC, Oh JY, Benight SJ and Bao Z, Adv. Funct. Mater, 2016, 26, 7254–7262. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oh JY, Rondeau-Gagné S, Chiu Y-C, Chortos A, Lissel F, Wang G-JN, Schroeder BC, Kurosawa T, Lopez J, Katsumata T, Xu J, Zhu C, Gu X, Bae W-G, Kim Y, Jin L, Chung JW, Tok JB-H and Bao Z, Nature, 2016, 539, 411–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruner C and Dauskardt R, Macromolecules, 2014, 47, 1117–1121. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodriquez D, Kim J-H, Root SE, Fei Z, Boufflet P, Heeney M, Kim T-S and Lipomi DJ, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, 2017, 9, 8855–8862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alkhadra MA, Root SE, Hilby KM, Rodriquez D, Sugiyama F and Lipomi DJ, Chem. Mater, 2017, 29, 10139–10149. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balar N and O’Connor BT, Macromolecules, 2017, 50, 8611–8618. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koch FPV, Rivnay J, Foster S, Müller C, Downing JM, Buchaca-Domingo E, Westacott P, Yu L, Yuan M, Baklar M, Fei Z, Luscombe C, McLachlan MA, Heeney M, Rumbles G, Silva C, Salleo A, Nelson J, Smith P and Stingelin N, Prog. Polym. Sci, 2013, 38, 1978–1989. [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Connor BT, Awartani OM and Balar N, MRS Bull, 2017, 42, 108–114. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Savagatrup S, Printz AD, O’Connor TF, Zaretski AV, Rodriquez D, Sawyer EJ, Rajan KM, Acosta RI, Root SE and Lipomi DJ, Energy Environ. Sci, 2014, 8, 55–80. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Savagatrup S, Printz AD, Wu H, Rajan KM, Sawyer EJ, Zaretski AV, Bettinger CJ and Lipomi DJ, Synth. Met, 2015, 203, 208–214. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Savagatrup S, Printz AD, Rodriquez D and Lipomi DJ, Macromolecules, 2014, 47, 1981–1992. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shen J, Fujita K, Matsumoto T, Hongo C, Misaki M, Ishida K, Mori A and Nishino T, Macromol. Chem. Phys, 2017, 218, 1700197. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li W, Hendriks KH, Wienk MM and Janssen RAJ, Acc. Chem. Res, 2016, 49, 78–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lipomi DJ and Bao Z, MRS Bull, 2017, 42, 93–97. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liang J, Tong K, Sun H and Pei Q, MRS Bull, 2017, 42, 131–137. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keum H, Mccormick M, Liu P, Zhang Y and Omenetto FG, Science, 2011, 333, 838–844.21836009 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang Z, Deng J, Sun X, Li H and Peng H, Adv. Mater, 2014, 26, 2643–2647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim D-H, Viventi J, Amsden JJ, Xiao J, Vigeland L, Kim Y-S, Blanco JA, Panilaitis B, Frechette ES, Contreras D, Kaplan DL, Omenetto FG, Huang Y, Hwang K-C, Zakin MR, Litt B and Rogers JA, Nat. Mater, 2010, 9, 511–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fu KK, Wang Z, Dai J, Carter M and Hu L, Chem. Mater, 2016, 28, 3527–3539. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Savagatrup S, Makaram AS, Burke DJ and Lipomi DJ, Adv. Funct. Mater, 2014, 24, 1169–1181. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Postema AR, Liou K, Wudl F and Smith P, Macromolecules, 1990, 23, 1842–1845. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yiu AT, Beaujuge PM, Lee OP, Woo CH, Toney MF and Fréchet JMJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2012, 134, 2180–2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ho V, Boudouris BW and Segalman RA, Macromolecules, 2010, 43, 7895–7899. [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Connor B, Chan EP, Chan C, Conrad BR, Richter LJ, Kline RJ, Heeney M, McCulloch I, Soles CL and DeLongchamp DM, ACS Nano, 2010, 4, 7538–7544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao Y, Zhao X, Zang Y, Di CA, Diao Y and Mei J, Macromolecules, 2015, 48, 2048–2053. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Savagatrup S, Zhao X, Chan E, Mei J and Lipomi DJ, Macromol. Rapid Commun, 2016, 37, 1623–1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koch FPV, Heeney M and Smith P, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2013, 135, 13699–13709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Torabi S, Jahani F, Van Severen I, Kanimozhi C, Patil S, Havenith RWA, Chiechi RC, Lutsen L, Vanderzande DJM, Cleij TJ, Hummelen JC and Koster LJA, Adv. Funct. Mater, 2015, 25, 150–157. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gentilini C, Boccalon M and Pasquato L, European J. Org. Chem, 2008, 19, 3308–3313. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Purc A, Sobczyk K, Sakagami Y, Ando A, Kamada K and Gryko DT, J. Mater. Chem. C, 2015, 3, 742–749. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tahk D, Lee HH and Khang DY, Macromolecules, 2009, 42, 7079–7083. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ito Y, Virkar AA, Mannsfeld S, Oh JH, Toney M, Locklin J and Bao Z, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2009, 131, 9396–9404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woo CH, Beaujuge PM, Holcombe TW, Lee OP and Fréchet JMJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2010, 132, 15547–15549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Root SE, Alkhadra MA, Rodriquez D, Printz AD and Lipomi DJ, Chem. Mater, 2017, 29, 2646–2654. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schmid SA, Yim KH, Chang MH, Zheng Z, Huck WTS, Friend RH, Kim JS and Herz LM, Phys. Rev. B, 2008, 77, 115338. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bricaud Q, Cravino A, Leriche P and Roncali J, Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells, 2009, 93, 1624–1629. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roncali J, Marque P, Garreau R, Gamier F and Lemaire M, Macromolecules, 1990, 23, 1347–1352. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roncali J, Garreau R, Yassar A, Marque P, Garnier F and Lemaire M, J. Phys. Chem, 1987, 91, 6706–6714. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kanimozhi C, Yaacobi-Gross N, Chou KW, Amassian A, Anthopoulos TD and Patil S, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2012, 134, 16532–16535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Noriega R, Rivnay J, Vandewal K, V Koch FP, Stingelin N, Smith P, Toney MF and Salleo A, Nat. Mater, 2013, 13, 1038–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mei J and Bao Z, Chem. Mater, 2014, 26, 604–615. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krebs FC, Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells, 2009, 93, 394–412. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Finn M III, Martens CJ, Zaretski AV, Roth B, Søndergaard RR, Krebs FC and Lipomi DJ, Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells, 2018, 174, 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim J-H, Lee I, Kim T-S, Rolston N, Watson BL and Dauskardt RH, MRS Bull, 2017, 42, 115–123. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.