Abstract

We present a selection design that couples S-adenosylmethionine–dependent methylation to growth. We demonstrate its use in improving the enzyme activities of not only N-type and O-type methyltransferases by 2-fold but also an acetyltransferase of another enzyme category when linked to a methylation pathway in Escherichia coli using adaptive laboratory evolution. We also demonstrate its application for drug discovery using a catechol O-methyltransferase and its inhibitors entacapone and tolcapone. Implementation of this design in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is also demonstrated.

Author summary

Many important biological processes require methylation, e.g., DNA methylation and synthesis of flavoring compounds, neurotransmitters, and antibiotics. Most methylation reactions in cells are catalyzed by S-adenosylmethionine (SAM)–dependent methyltransferases (Mtases) using SAM as a methyl donor. Thus, SAM-dependent Mtases have become an important enzyme category of biotechnological interests and as healthcare targets. However, functional implementation and engineering of SAM-dependent Mtases remains difficult and is neither cost effective nor high throughput. Here, we are able to address these challenges by establishing a synthetic biology approach, which links Mtase activity to cell growth such that higher Mtase activity ultimately leads to faster cell growth. We show that better-performing variants of the examined Mtases can be readily obtained by growth selection after repetitive cell passages. We also demonstrate the usefulness of our approach for discovery of Mtase-specific drug candidates. We further show our approach is not only applicable in bacteria, exemplified by Escherichia coli, but also in eurkaryotic organisms such as budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

Introduction

Methylation is the transfer of a methyl group from one molecule to another. Its importance in gaining bioactivity and acquiring bioavailability of drugs has been recognized by chemists for some time [1]. Chemical methylation ordinarily utilizes noxious reagents and generates toxic waste and often lacks regioselectivity [2]. In contrast, enzymatic methylation is specific, environmentally friendly, and safer to work with.

Most methylation in cells takes place by S-adenosylmethionine–dependent methyltransferases (SAM-dependent Mtases), using SAM as the methyl donor. SAM-dependent methylation is involved in many important biological processes, including epigenetics and synthesis of a wide range of secondary metabolites (e.g., flavonoids, neurotransmitters, antibiotics). In fact, SAM is one of the most commonly used cofactors in cellular metabolism, second only to ATP [3]. SAM-dependent Mtases have become an important enzyme category, used either as biocatalysts, as part of fermentative production pathways in biotechnical and chemical industries [2–4], or as drug targets in the pharmaceutical industry [5,6].

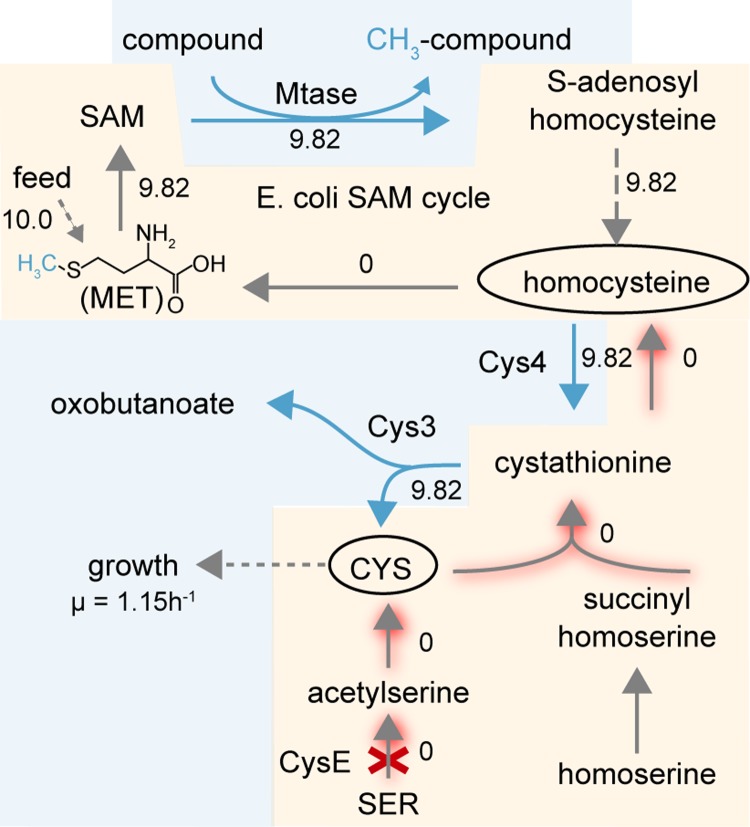

Implementing and engineering functional SAM-dependent Mtases is difficult since all existing assays lack robustness, are not cost effective, and are not generalizable to all types of Mtases or high throughput. Consequently, study and engineering of Mtases or building efficient methylation-dependent pathways is hard to achieve. We designed an in vivo synthetic selection system by coupling SAM-dependent methylation to growth via a homocysteine intermediate of the SAM cycle. This selection system design was first implemented in E. coli by deleting serine acetyltransferase (cysE) to prevent endogenous homocysteine and cysteine synthesis. We diverged homocysteine of the SAM cycle to cysteine using heterologously expressed yeast cystathionine-β-synthase (Cys4) and cystathionine-γ-lyase (Cys3) (Figs 1 and S1). Effectively, this design couples methylation to the conversion of exogenous methionine to the biosynthesis of cysteine, a required amino acid for growth. This growth-coupled design was computationally validated using a genome-scale metabolic model (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Illustration of growth-coupled methyltransferase selection system design in E. coli.

Native reactions are colored in gray, and heterologous reactions are colored in cyan. Dashed lines represent multiple enzymatic reactions. Red shaded lines indicate an inactive pathway after gene deletion (red cross). Metabolically related reactions are boxed together. Numbers shown are simulated metabolic fluxes as mmol gram per dry weight per hour. μ indicates the growth rate. CYS, cysteine; cysE, serine acetyltransferase; Cys3, cystathionine-γ-lyase; Cys4, cystathionine-β-synthase; MET, methionine; Mtase, methyltransferase; SAM, S-adenosylmethionine; SER, serine.

Results

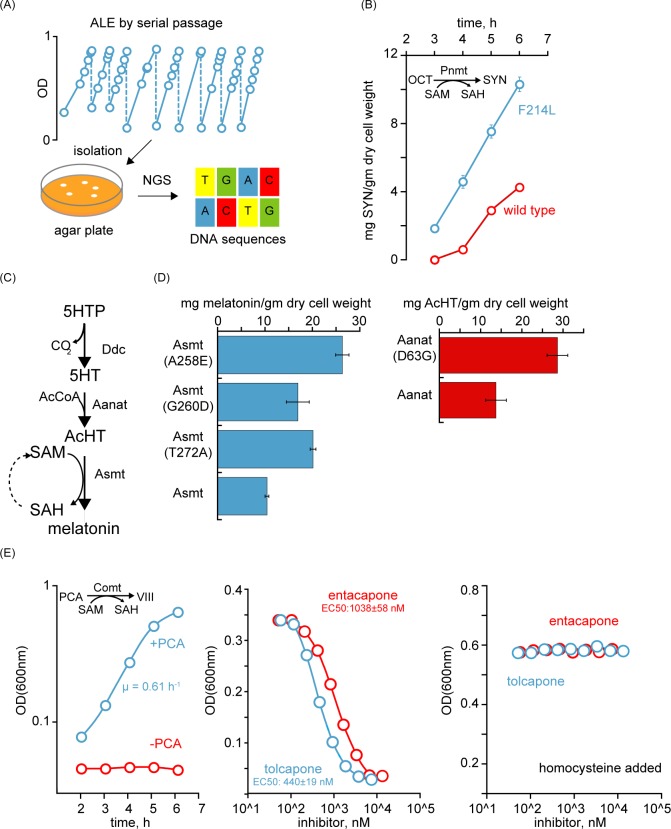

We demonstrate the use of our system to improve enzyme properties. Using adaptive laboratory evolution (ALE) with growth selection, we first achieved directed evolution of phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (Pnmt) using a non-natural substrate, octopamine (OCT). In recent years, ALE has emerged as a productive approach to address a wide range of biological questions [7–9]. We implemented an ALE-driven workflow to demonstrate our selection system because of the operational simplicity of ALE (serial passages), its ultra-high–throughput screening capability (over 10 million cells per passage), its ability to engage phenotype-driven in vivo evolution, and the affordability of DNA resequencing (Fig 2A). Following ALE, isolated strains were characterized and were subjected to full DNA resequencing. Mutations in E. coli cfa, involved in phospholipid synthesis, were identified in all non-growth–coupled isolates. The cfa gene encodes for a SAM-dependent Mtase, suggesting its role as a competing Mtase during ALE. On the other hand, a Pnmt (F214L) mutation was present in growth-coupled isolates, and a cell-based characterization showed that it led to approximately 2-fold activity improvement on synephrine (SYN) synthesis (Fig 2B).

Fig 2. Uses of the Mtase selection system.

(A) ALE-driven workflow. (B) In vivo enzymatic comparison of wild-type Pnmt and variant shown in time course. n = 4, and error bars indicate SD. (C) The melatonin pathway. (D) In vivo enzymatic activity of Asmt and Aanat variants after 6 h cell growth. See S2 Fig for details. n = 3, and error bars indicate SD. (E) Comt-dependent growth shown using an evolved isolate bearing RpoC (A328P). μ indicates the growth rate. Inhibitor titration curves of the same strain in the presence or absence of homocysteine. n = 4, and error bars are SD. Underlying data can be found in S1 Data. Aanat, aralkylamine N-acetyltransferase; AcHT, acetylserotonin; AcCoA, acetyl-CoA; ALE, adaptive laboratory evolution; Asmt, acetylserotonine O-methyltransferase; Comt, catechol O-methyltransferase; Ddc, aromatic-amino-acid decarboxylase; Mtase, methyltransferase; NGS, next-generation sequencing; OCT, octopamine; OD, optical density; PCA, protocatechuic acid; Pnmt, phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase; RpoC, RNA polymerase subunit beta; SAH, S-adenosylhomocysteine; SAM, S-adenosylmethionine; SD, standard deviation; SYN, synephrine; VIII, vanillic acid; 5HT, serotonin; 5HTP, 5-hydroxytryptophan.

Most often, Mtase substrates may not be readily available in large quantities or even membrane permeable in order to perform directed enzyme evolution in vivo, and it may then only be feasible to engage an active metabolic pathway. We thus applied our selection system to evolve a methylation-dependent pathway. The chosen candidate pathway was a de novo three-step melatonin biosynthesis pathway from 5-hydroxytryptophan (5HTP). It consisted of three enzymatic steps: decarboxylation (aromatic-amino-acid decarboxylase [Ddc]), acetylation (aralkylamine N-acetyltransferase [Aanat]), and methylation (acetylserotonine O-methyltransferase [Asmt]) (Fig 2C). By using ALE, Asmt was evolved in vivo, and three sequence variants (A258E, G260D, and T272A) were discovered (Fig 2D). All variants showed improved turnover compared to wild-type Asmt under physiological conditions, with the highest improvement observed in A258E (approximately 2.5-fold). It was additionally discovered that high levels of ddc expression from a plasmid caused genetic instability, and mutations in cfa could be seen in non-melatonin–producing cells, affirming its role as an unwanted sink for SAM in E. coli. Upon incorporating Asmt (A258E), a single copy of ddc, and cfa deletion in the background strain, Aanat was further evolved in the next ALE, and the D63G mutation was identified, leading to approximately 2-fold activity improvement (Fig 2D). These results demonstrated the usefulness of this growth selection system for directed evolution of enzymes or metabolic pathways when linked to a methylation reaction.

We next demonstrate the use of our system for drug discovery. SAM-dependent Mtases participate in many important cellular functions and are targeted by a number of drug development programs (such as DNA or histone Mtase inhibitors) [6]. We applied our selection system on catechol O-methyltransferase (Comt), a known drug target for treating Parkinson's disease [5]. Cells bearing human Comt were evolved to grow at high rates using ALE (Fig 2E). All isolates were growth-coupled to Comt activity. Resequencing results showed the comt gene did not acquire any mutations, while many isolates accumulated mutations on RpoC (such as A328P, E1146A, or E1146G), a subunit of E. coli RNA polymerase, suggesting a host factor effect. The suitability of using evolved cells to screen Comt inhibitors by growth was evaluated next by determining Z-factor in a 96-well format [10]. The Z-prime value was calculated to be between 0.87 to 0.97 when cells were grown for 3 h or more, indicating a high-throughput-screening (HTS)–compatible assay with large separation (Fig 2E and S1 Table). We then tested one evolved isolate with two known Comt inhibitors: entacapone and tolcapone, respectively. Both drugs reduced Comt-dependent cell growth at concentrations as low as 200 nM, with a slightly higher potency observed for tolcapone (Fig 2E). Both inhibitors were highly specific to Comt and showed no observable adverse effects on other cellular proteins (such as heterologous Cys3 and Cys4 or the essential E. coli proteins) when homocysteine was additionally supplemented, implying a general suitability of our selection system for in vivo Comt inhibitor screening (Fig 2E).

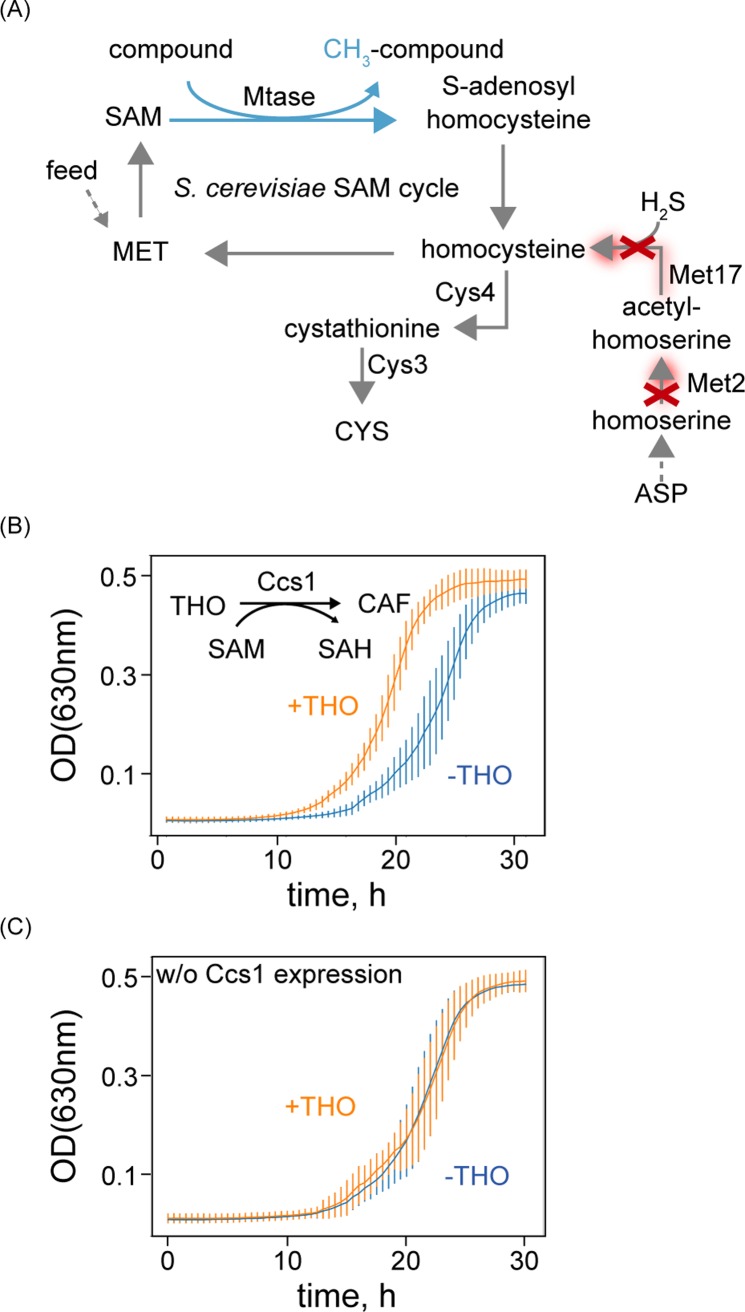

Lastly, we implemented our design in budding yeast S. cerevisiae. S. cerevisiae is an industrially important production host with growing interest for biobased production of value-added methylated products [11]. It is also a well-studied eukaryotic model organism expressing diverse cellular Mtases [12]. In contrast to E. coli, yeast is capable of synthesizing cysteine through reverse transsulfuration from homocysteine because of the natural appearance of the CYS3 and CYS4 genes (Fig 3A) [13]. Therefore, blockage of homocysteine biosynthesis from aspartate is required to enable the selection, and this was achieved by deleting the genes encoding homoserine O-acetyltransferase (MET2) and O-acetylhomoserine sulfhydrylase (MET17). Additional gene deletion of phosphatidylethanolamine methyltransferase (CHO2) and phospholipid methyltransferase (OPI3) required for phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis was performed to remove potential competing native Mtases for SAM [14]. In this quadruple knock-out strain, the heterologous caffeine synthase I gene (CCS1), encoding an N-Mtase from Coffea arabica acting on theobromine to synthesize caffeine, was introduced. The presence of Ccs1 conferred growth advantage when exogenous theobromine was supplemented compared to nonsupplemented cells, affirming the applicability of the design in yeast (Fig 3B). Control cells without Ccs1 expression showed similar growth regardless of theobromine supplementation (Fig 3C). Acknowledging the large number of native Mtases in yeast [12], this phenotype might be the result of the activity of remaining native Mtases for homocysteine synthesis required for growth.

Fig 3. Demonstration of Mtase selection design in S. cerevisiae.

(A) Illustration of growth-coupled Mtase selection design in S. cerevisiae. Native reactions are colored in gray, and heterologous reactions are colored in cyan. Dashed lines represent multiple enzymatic reactions. Red crosses indicate gene deletion. Red shaded lines indicate inactive reactions after gene deletion (red cross). Cofactors, byproducts, and co-substrates are omitted. Growth of S. cerevisiae expressing heterologous Ccs1 (B) and empty plasmid control cells (C) in the presence (orange) and absence (blue) of theobromine with methionine. Error bar indicates SD. Underlying data can be found in S1 Data. ASP, aspartic acid; CAF, caffeine; CCS1, caffeine synthase I; CYS, cysteine; Cys3, cystathionine-γ-lyase; Cys4, cystathionine-β-synthase; MET, methionine; Mtase, methyltransferase; OD, optical density; SAH, S-adenosylhomocysteine; SAM, S-adenosylmethionine; THO, theobromine; w/o, without.

Discussion

In summary, we have designed and validated a methylation-dependent growth selection system for Mtases. Not only did this selection system lead to the discovery of causal mutations that improve enzyme properties of heterologous Mtases and acetyltransferase, but it also demonstrated usefulness in drug discovery and the identification of critical host factors. Further applications of this technology can be used to acquire in-depth understanding of Mtases (such as their evolutionary path and governing factors for substrate specificity) or to engineer pathways or host cells of metabolic engineering interests. We have implemented our design in E. coli and S. cerevisiae; however, the conceptual design of this selection is transferable to any organism with an active SAM cycle. Implementing this selection system in higher eukaryotic cells (such as mammalian cells) is particularly valuable for drug development since permeability and stability of promising drug candidates can be determined at early stages. Overall, the described selection is robust, generalizable, compatible with HTS, and widely applicable, and it is likely to become a useful and valuable tool for the chemical biology and metabolic engineering communities.

Materials and methods

Microbial strains, media, and growth conditions

The E. coli BW25113 strain and derivatives were used throughout this study. Genome engineering of E. coli was facilitated by λ-red recombination, P1 transduction, and/or site-specific Tn7 transposon [15,16]. S. cerevisiae CEN.PK 102-5B (MATa) was used as background yeast strain for the engineered yeast strains. Genome engineering of S. cerevisiae was facilitated by CRISPR/Cas9 [17,18], and transformations were performed with the lithium acetate/single-stranded carrier DNA/PEG method [19]. A list of strains used is shown in S2 Table. Unless stated otherwise, all E. coli strains were maintained at 37°C in LB (Lennox) (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), 2xYT, or M9 media containing M9 minimal salts (BD Difco, BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), 2 mM MgSO4, 100 μM CaCl2, 500-fold diluted trace minerals (10 g/L FeCl3·6H2O, 2 g/L ZnSO4·7H2O, 0.4 g/L CuCl2·2H2O, 1 g/L MnSO4·H2O, 0.6 g/L CoCl2·6H2O, and 1.6 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]), 1× ATCC Vitamin Supplement (ATCC MD-VS), and 0.2% glucose (w/v). Unless stated otherwise, ampicillin and spectinomycin were used at 50 mg/L; chloramphenicol and kanamycin were used at 25 mg/L. Yeast strains were cultured on either rich yeast extract-peptone dextrose (YPD), yeast synthetic drop-out media (lacking the proper amino acids for selection) (Sigma Aldrich), or Delft medium [20] with 2% glucose. Delft medium was sterilized by filtration. All Δcho2- and Δopi3-derived strains were maintained on media supplemented with 1 mM choline chloride (Sigma Aldrich), except for YPD medium.

Plasmids

Plasmid DNA assemblies were performed by Gibson Assembly, USER cloning, or the EasyCloning method [20–22]. E. coli TOP10 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and DH5α were used for plasmid propagations. For propagation of yeast plasmids, 100 mg/L ampicillin was used. A list of plasmids used is summarized in S3 Table.

ALE

All ALE experiments were performed at 37°C using M9 supplemented with 50 mg/L methionine and substrates, unless stated otherwise. Cell passages were performed automatically according to previously described [23], and six lineages of the initial strain were usually maintained. OCT and PCA at 50 mg/L were supplemented for Pnmt and Comt evolution, respectively. The melatonin pathway was evolved in the presence of 100 mg/L of methionine and 100 mg/L of 5HTP. Antibiotics were not supplied during ALE.

Strain construction for methylation-dependent selection

The E. coli ECAH2 strain (ΔcysE), derived from JW3582 of the Keio Collection [24], was used as the host strain to test methylation-dependent growth in the presence of pHM11. The pHM11 plasmid harbored cys3 and cys4 from S. cerevisiae S288C. Homocysteine and Cys3/Cys4-dependent cysteine synthesis was demonstrated by transforming ECAH2 with pHM11. The transformed strain, ECAH3, was allowed to grow on an M9 plate containing 50 mg/L homocysteine at 37°C for 24 h to demonstrate homocysteine-dependent growth. The ECAH6 and ECAH7 strains were used for Pnmt and Comt evolution using ALE. All ΔcysE-derived strains were maintained on LB plates supplemented with 25 mg/L cysteine.

The E. coli HMP236 strain was initially used to evolve the melatonin pathway from 5HTP (S2 Table). It contained two plasmids, pHM11 and pHM12. Its parent strain was HMP221 with the following genome modifications: FolE (T198I), YnbB (V197A), ΔtnaA, ΔcysE, ΔmetE, and ΔmetH. Deletion of tnaA was to prevent 5HTP degradation. Deletion of metE and metH was to prevent a reverse methionine-to-homocysteine synthesis via methionine synthase encoded by both genes, but it was later determined not to be required.

The E. coli HMP579 was used for the subsequent melatonin pathway evolution. It carried two plasmids, pHM70 and pHM79. The pHM70 plasmid was modified from pHM11 with an insertion of Asmt (A258E). The second plasmid, pHM79, was not required in this study because of 5HTP feeding. Its parent strain was HMP553, carrying a single chromosomal copy of ddc and aanat. The ddc and aanat genes were introduced to the attTn7 site using pGRG25.

The S. cerevisiae SCAH124 strain, derived from S. cerevisiae CEN.PK102-5B (MATa), was constructed by sequential CRISPR/Cas9-facilitated full ORF markerfree knock-out of MET17, CHO2, OPI3, and MET2 mediated by homology-directed recombination using guide RNA (gRNA)-expressing plasmids PL_01_A2, PL_01_A3, PL_01_C8, and PL_01_E1 and two linear DNA fragments homologous to the flanking regions up- and downstream of the targeted ORF, as well as PL_01_A9 with CAS9. The following gRNA sequences were used for Cas9-targeting of indicated ORF and identified with the webservice CRISPy adapted for the S. cerevisiae CEN.PK genome sequence [25]: MET17 (5′-GATACTGTTCAACTACACGC-3′), CHO2 (5′-ACCACCTGTAACCCACGATA-3′), OPI3 (5′- GCAGAAACAACCAGCCCCGC-3′) and MET2 (5′- GTAATTTGTCATGCCTTGAC-3′). SCAH134 and SCAH138, derived from SCAH124 and harboring the Mtase gene CCS1 (PL_01_D2) and an empty vector (pRS415U), respectively, were used for demonstration of selection design in S. cerevisiae.

DNA resequencing and data analysis

Total DNA was extracted using a PureLink Genomic DNA Kit (Invitrogen) and was processed either commercially by Beckman Coulter Genomics (Danvers, MA, USA) or in house. When prepared in house, DNA libraries were prepared using a Kapa Hyper Prep Library Prep Kit (Roche Molecular Systems, Pleasanton, CA, USA). DNA samples were sequenced using Illumina MiSeq or NextSeq.

Trimmomatic tool (v0.32-v0.35) was used for quality trimming of raw sequencing data with "CROP:145 HEADCROP:15 SLIDINGWINDOW:4:15 MINLEN:30" parameters [26]. Breseq (v0.27.1) was employed for variant calling on processed sequencing data with "-j 4 -b 20" parameters [27]. E. coli BW25113 genome sequence with NCBI accession CP009273 was used as reference along with other relevant parts and plasmids.

Compound analysis

All compounds were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. PCA and its methylated product vanillic acid (VIII) were quantified using a Dionex 3000 HPLC system (Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) equipped with a Cortecs UPLC T3 column from Waters (Milford, MA, USA) and a guard column from Phenomenex (Torrance, CA, USA). The column temperature was set to 30°C, and the mobile phase consisted of a 0.1% formic acid and acetonitrile. Runtime was 11 min, including 4.2 min separation without acetonitrile, 1 min washing with 75% acetonitrile, and an additional 4.5 min run without acetonitrile. The flow rate was constant at 0.3 ml/min, and the injection volume was 1 μl. Both compounds were detected by UV at wavelengths 210, 240, and 300 nm as well as a 3D UV scan. HPLC data were processed using Chromeleon 7.1.3 software (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and compound concentrations were calculated using calibration curves.

5HTP, serotonin (HT), acetylserotonin (AcHT), and melatonin were quantified using a Dionex 3000 HPLC system equipped with a Zorbax Eclipse Plus C18 column (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and a guard column from Phenomenex. To achieve separation, the column was heated to 30°C, and the mobile phase consisted of a 0.05% acetate and a variable amount of acetonitrile. Runtime was 12 min, including 10 min of separation, whereas acetonitrile was reduced from 95% to 38.7% in 9.4 min. After holding 0.6 min, acetonitrile concentration was returned to 95% in 1 min and was held till the end of the run. The flow rate was set to 1 ml/min, and the injection volume was 1 μl. Elution of the compounds was detected by UV at wavelengths 210 nm, 240 nm, 280 nm, and 300 nm as well as a 3D UV scan. HPLC data were processed using Chromeleon 7.1.3 software (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and compound concentrations were calculated using calibration curves.

OCT was quantified using a Dionex 3000 HPLC system equipped with a Cortecs UPLC T3 column from Waters and a guard column from Phenomenex. The column temperature was set to 30°C, and the mobile phase consisted of 0.1% formic acid and acetonitrile. Runtime was 9 min, including 2.5 min separation without acetonitrile, 0.5 min washing with 70% acetonitrile, and an additional 5.5-min run without acetonitrile. The flow rate was constant at 0.3 ml/min, and the injection volume was 1 μl. OCT was detected by UV at wavelengths 210, 240, and 300 nm as well as a 3D UV scan. SYN was detected by LC-MS (Fusion, Thermo Fisher Scientific) in the positive full-scan mode using the same separation profile as OCT quantification. SYN was detected as [M + H]+ m/z 168.10191 with a mass accuracy of 2.2 ppm. Data were processed using Chromeleon 7.1.3 and X-calibur 4.1 from Thermo Fisher Scientific, and compound concentrations were calculated using calibration curves.

Growth measurements

Growth of E. coli was measured using a Duetz 96-well low well system (Enzyscreen, Heemstede, The Netherlands) coupled to a humidified Innova 44 shaker (5 cm orbit) (New Brunswick Scientific, Edison, NJ, USA) at 37°C and 300 rpm. Seed cells were grown in 400 μl LB in the presence of appropriate antibiotics for 4–5 h in 96-well deep well plates. When transferred to M9, 10 μl of cells were added to 400 μl of M9 with 25 mg/L cysteine and antibiotics. After overnight growth, cells were added to 150 μl of fresh M9 with 50 mg/L of methionine and 50 mg/L methylation substrates to approximately 4% in a 96-well low well plate. Changes in optical density at 600 nm (OD600) were recorded using a SynergyMx microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA). Growth rates were calculated from an average of four independent biological replicates using KaleidaGraph 4.1.3.

Six biological replicates of S. cerevisiae SCAH134 and SCAH138 were inoculated from seed cultures to similar ODs for sulfur amino acid starvation in Delft medium supplemented with histidine, uracil, and choline chloride and incubated for approximately 24 h. The seed cultures were grown in yeast synthetic complete medium without leucine, supplemented with choline chloride, for approximately 25 h. Both replicate seed cultures and starvation cultures were cultured in a total volume of 500 μl in 96-deep well plates at 30°C/300 rpm. Upon completion of starvation, cells were transferred to Delft medium supplemented with histidine, uracil, choline chloride, 1 mM L-methionine, and with/without 1 mM theobromine (Sigma Aldrich) to similar ODs and to a final volume of 150 μl in a flat-bottomed microtiterplate. Two technical replicates were inoculated for each of the six biological replicates. Growth was recorded in a microtiterplate reader (ELx808 Absorbance Reader, BioTek Instruments) with continuous shaking at strong setting, at 30°C, and with recording of absorbance at 630 nm every 30 min. The cultures had incubated in the plate reader 30 min prior to the first reading at time 0 h. Growth curves were plotted using mean absorbance of the replicates for 30 h. Blank media values were not subtracted.

Growth inhibition assay using entacapone and tolcapone

HL1818 was used to test the inhibition effect of entacapone and tolcapone. Cells were prepared for growth measurement as described above. The test growth medium was M9 with 50 mg/L PCA, 50 mg/L methionine, 1% DMSO, and various amount of inhibitors. The stock concentration of entacapone and tolcapone was 20 g/L dissolved in DMSO. To the positive controls, 50 mg/L homocysteine was additionally included so that effects of the drugs on E. coli cells (such as those other than Comt) could be determined. A drug concentration response curve was plotted using average OD600 after 6 h growth from three independent biological replicates. The EC50 values were calculated using OriginPro 2018b (version b9.5.5.409).

Characterizations of Pnmt activity in vivo

Measurements of SYN production were performed using a Duetz 96-well deep well system (Enzyscreen) coupled to an Innova 44 shaker (5 cm orbit) (New Brunswick Scientific) at 37°C and 300 rpm. HL1815 and HL1816 were used to measure SYN production (S1 Table). Seed cells were grown in LB in the presence of chloramphenicol for 4–5 h and thereafter grew in M9 overnight. Fresh M9 containing 200 mg/L OCT was inoculated with seed culture to 4%. These cells were transferred to a 96-well deep well plate, and each well contained 400 μl. 200 μl samples were withdrawn periodically for exometabolites analysis, while the remaining 200 μl cells were used to determine OD values using a SynergyMx microplate reader (BioTek). In vivo enzyme activity was averaged from four independent biological measurements normalized to dried cell weight. The conversion factor from OD to dried cell weight is 1 (i.e., 1 OD = 1 g/L) for our setup. It was observed that Pnmt activity was biomass dependent.

Characterizations of Asmt and Aanat activity in vivo

A Duetz 24-well deep well system (Enzyscreen) coupled to an Innova 44 shaker (5 cm orbit) (New Brunswick Scientific) was used. Physiological Asmt activity was determined by growing HMP231, HMP416, HMP416, HMP417, and HMP418 in 2 ml M9 supplemented with 100 mg/L AcHT at 37°C with shaking at 300 rpm. Samples were withdrawn periodically for exometabolites analysis using HPLC and OD measurements. Physiological Aanat activity was measured using HMP850 and HMP851 in the presence of 100 mg/L HT. In vivo enzyme activity was averaged from three independent biological measurements normalized to dried cell weight. It was observed that Asmt and Aanat activity was biomass independent.

Validation of selection systems using an E. coli genome-scale metabolic model

Validation of the selection system design was performed using the most recent E. coli genome-scale metabolic model [28], which computes the flux states of the entire metabolic network. Following established procedures [29], the cysE gene was “knocked out” in silico by setting the upper and lower bounds of the metabolic reaction it catalyzes to 0. Metabolic reactions catalyzed by Cys3 and Cys4 were inserted into the metabolic model. Additionally, a methylation-dependent reaction was inserted into the model (Pnmt, Comt, or Asmt). The metabolic model was then solved for its flux state using linear programming by setting cell growth as the objective. All model simulations were performed using the python package COBRApy 0.7.0 in Python 2.7 [30].

Supporting information

Cys3, cystathionine-γ-lyase; Cys4, cystathionine-β-synthase.

(TIF)

Underlying data can be found in S1 Data. Aanat, aralkylamine N-acetyltransferase; Asmt, acetylserotonine O-methyltransferase.

(TIF)

Comt, catechol O-methyltransferase.

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

Authors thank Christina Lenhard, Camilla C. Andersen, Ksenia Chekina, Svetlana Sherstyk, Charlotte Brøchner, Elsayed T.T. Mohamed, Mohammad Radi, Ida Bonde, Denis Shepelin, Inger R. Madsen and Jie Zhang for their assistance; Se Hyeuk Kim, Rebecca Lennen, Scott J. Harrison, Tobias Klein, and Miguel A. Campodonico Alt for discussion.

Abbreviations

- Aanat

aralkylamine N-acetyltransferase

- AcCoA

acetyl-CoA

- AcHT

acetylserotonin

- ALE

adaptive laboratory evolution

- Asmt

acetylserotonine O-methyltransferase

- ASP

aspartic acid

- CCS1

caffeine synthase I

- CHO2

phosphatidylethanolamine methyltransferase

- Comt

catechol O-methyltransferase

- CYS

cysteine

- cysE

serine acetyltransferase

- Cys3

cystathionine-γ-lyase

- Cys4

cystathionine-β-synthase

- Ddc

aromatic-amino-acid decarboxylase

- gRNA

guide RNA

- HT

serotonin

- HTS

high-throughput screening

- MET

methionine

- MET2

homoserine O-acetyltransferase

- MET17

O-acetylhomoserine sulfhydrylase

- Mtase

methyltransferase

- NGS

next-generation sequencing

- OCT

octopamine

- OD

optical density

- OPI3

phospholipid methyltransferase

- PCA

protocatechuic acid

- Pnmt

phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase

- RpoC

RNA polymerase subunit beta

- SAH

S-adenosylhomocysteine

- SAM

S-adenosylmethionine

- SD

standard deviation

- SER

serine

- SYN

synephrine

- VIII

vanillic acid

- YPD

yeast extract-peptone dextrose

- 5HTP

5-hydroxytryptophan

Data Availability

All resequencing files are available from the ArrayExpress (EMBL-EBI) database (accession number E-MTAB-6779). Materials used in this study are available upon a reasonable request.

Funding Statement

Novo Nordisk Foundation http://novonordiskfonden.dk/en (grant number NNF10CC1016517). The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Schönherr H, Cernak T. Profound methyl effects in drug discovery and a call for new C-H methylation reactions. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2013;52(47):12256–67. 10.1002/anie.201303207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Struck AW, Thompson ML, Wong LS, Micklefield J. S-adenosyl-methionine-dependent methyltransferases: highly versatile enzymes in biocatalysis, biosynthesis and other biotechnological applications. Chembiochem. 2012;13(18):2642–55. 10.1002/cbic.201200556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cantoni GL. Biological methylation: selected aspects. Annu Rev Biochem. 1975;44:435–51. 10.1146/annurev.bi.44.070175.002251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huber TD, Johnson BR, Zhang J, Thorson JS. AdoMet analog synthesis and utilization: current state of the art. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2016;42:189–197. 10.1016/j.copbio.2016.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lerner C, Jakob-Roetne R, Buettelmann B, Ehler A, Rudolph M, Rodríguez Sarmiento RM. Design of Potent and Druglike Nonphenolic Inhibitors for Catechol O-Methyltransferase Derived from a Fragment Screening Approach Targeting the S-Adenosyl-l-methionine Pocket. J Med Chem. 2016;59:10163–10175. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones PA, Issa JP, Baylin S. Targeting the cancer epigenome for therapy. Nat Rev Genet. 2016;17:630–41. 10.1038/nrg.2016.93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Portnoy VA, Bezdan D, Zengler K. Adaptive laboratory evolution—harnessing the power of biology for metabolic engineering. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2011;22:590–4. 10.1016/j.copbio.2011.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dragosits M, Mattanovich D. Adaptive laboratory evolution—principles and applications for biotechnology. Microb Cell Fact. 2013;12:64 10.1186/1475-2859-12-64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guzmán GI, Utrilla J, Nurk S, Brunk E, Monk JM, Ebrahim A, Palsson BO, Feist AM. Model-driven discovery of underground metabolic functions in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:929–34. 10.1073/pnas.1414218112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang JH, Chung TD, Oldenburg KR. A Simple Statistical Parameter for Use in Evaluation and Validation of High Throughput Screening Assays. J Biomol Screen. 1999;4:67–73. 10.1177/108705719900400206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galanie S, Thodey K, Trenchard IJ, Filsinger Interrante M, Smolke CD. Complete biosynthesis of opioids in yeast. Science. 2015;349:1095–100. 10.1126/science.aac9373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wlodarski T, Kutner J, Towpik J, Knizewski L, Rychlewski L, Kudlicki A, Rowicka M, Dziembowski A, Ginalsky K. Comprehensive Structural and Substrate Specificity Classification of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Methyltransferome. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(8):e23168 10.1371/journal.pone.0023168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas D, Surdin Kerjan Y. Metabolism of sulfur amino acids in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61(4):503–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sadhu MJ, Moresco JJ, Zimmer AD, Yates JR 3rd, Rine J. Multiple inputs control sulfur-containing amino acid synthesis in Saccharomyes cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell. 2014;25(10):1653–65. 10.1091/mbc.E13-12-0755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(12):6640–5. 10.1073/pnas.120163297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKenzie GJ, Craig NL. Fast, easy and efficient: site-specific insertion of transgenes into enterobacterial chromosomes using Tn7 without need for selection of the insertion event. BMC Microbiol. 2006;6:39 10.1186/1471-2180-6-39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reider Apel A, d’Espaux L, Wehrs M, Sachs D, Li RA, Tong GJ, Garber M, Nnadi O, Zhuang W, Hillson NJ, Keasling JD, Mukhopadhyay A. A Cas9-based toolkit to program gene expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1017;45(1):496–508. 10.1093/nar/gkw1023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DiCarlo JE, Norville JE, Mali P, Rios X, Aach J, Church GM. Genome engineering in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using CRISPR-Cas systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(7):4336–43 10.1093/nar/gkt135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gietz RD, Schiestl RH. Quick and easy yeast transformation using the LiAc/SS carrier DNA/PEG method. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2(1):35–7. 10.1038/nprot.2007.14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jensen NB, Strucko T, Kildegaard KR, David F, Maury J, Mortensen UH, Forster J, Nielsen J, Borodina I. EasyClone: method for iterative chromosomal integration of multiple genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast Res 2014;14(2):238–48. 10.1111/1567-1364.12118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gibson DG, Young L, Chuang RY, Venter JC, Hutchison CA 3rd, Smith HO. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat Methods. 2009;6:343–5. 10.1038/nmeth.1318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nour-Eldin HH, Geu-Flores F, Halkier BA. USER cloning and USER fusion: the ideal cloning techniques for small and big laboratories. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;643:185–200. 10.1007/978-1-60761-723-5_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.LaCroix RA, Sandberg TE, O'Brien EJ, Utrilla J, Ebrahim A, Guzman GI, Szubin R, Palsson BO, Feist AM. Use of adaptive laboratory evolution to discover key mutations enabling rapid growth of Escherichia coli K-12 MG1655 on glucose minimal medium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81:17–30. 10.1128/AEM.02246-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baba T, Ara T, Hasegawa M, Takai Y, Okumura Y, Baba M, et al. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol Syst Biol. 2006;2:2006.0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ronda C, Pedersen LE, Hansen HG, Kallehauge TB, Betenbaugh MJ, Nielsen AT, Kildegaard HF. Accelerating genome editing in CHO cells using CRISPR Cas9 and CRISPy, a webbased target finding tool. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2014. August;111(8):1604–16. 10.1002/bit.25233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(15):2114–20. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deatherage DE, Barrick JE. Identification of mutations in laboratory-evolved microbes from next-generation sequencing data using breseq. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1151:165–88. 10.1007/978-1-4939-0554-6_12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Monk JM, Lloyd CJ, Brunk E, Mih N, Sastry A, King Z, et al. iML1515, a knowledgebase that computes Escherichia coli traits. Nat Biotechnol. 2017;35(10):904–908. 10.1038/nbt.3956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Brien EJ, Monk JM, Palsson BO. Using Genome-scale Models to Predict Biological Capabilities. Cell. 2015;161(5):971–987. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ebrahim A, Lerman JA, Palsson BO, Hyduke DR. COBRApy: COnstraints-Based Reconstruction and Analysis for Python. BMC Syst Biol. 2013;7:74 10.1186/1752-0509-7-74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Cys3, cystathionine-γ-lyase; Cys4, cystathionine-β-synthase.

(TIF)

Underlying data can be found in S1 Data. Aanat, aralkylamine N-acetyltransferase; Asmt, acetylserotonine O-methyltransferase.

(TIF)

Comt, catechol O-methyltransferase.

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All resequencing files are available from the ArrayExpress (EMBL-EBI) database (accession number E-MTAB-6779). Materials used in this study are available upon a reasonable request.