Abstract

Feedstock aromatic compounds are compelling low-cost starting points from which molecular complexity can be generated rapidly via oxidative dearomatization. Oxidative dearomatizations commonly rely heavily on hypervalent iodine or heavy metals to provide the requisite thermodynamic driving force for overcoming aromatic stabilization energy. This article describes oxidative dearomatizations of 2-(hydroxymethyl)phenols via their derived bis(dichloroacetates) using hydrogen peroxide as a mild oxidant that intercepts a transient quinone methide. A stereochemical study revealed that the reaction proceeds by a new mechanism relative to other phenol dearomatizations and is complementary to extant methods that rely on hypervalent iodine. Using a new chiral phase-transfer catalyst, the first asymmetric syntheses of 1-oxaspiro[2.5]octa-5,7-dien-4-ones were reported. The synthetic utility of the derived 1-oxaspiro[2.5]octadienones products is demonstrated in a downstream complexity-generating transformation.

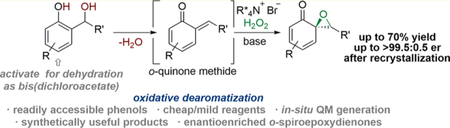

Graphical Abstract

1. INTRODUCTION

Oxidative dearomatizations of feedstock arenes, including phenols, are useful in delivering functionalized, complex organic building blocks.1 These processes often rely on excess, and in some cases costly, hypervalent iodine or heavy metal-based (i.e., lead and bismuth) reagents which can give rise to hazardous byproducts;2 this characteristic may counterbalance or overshadow the benefit of using inexpensive feedstock precursors. Reactions using catalytic or heavy metal-free conditions with benign oxidants, such as oxygen or hydrogen peroxide, have seldom been explored, especially in asymmetric fashion.3 Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is especially appealing as an oxidant due to its high effciency, abundance, and favorable byproduct profile (i.e., H2O).4

A recent report from these laboratories employed the Adler−Becker oxidation as the initiating step in a cascade sequence for the synthesis of highly functionalized hetero-cycles.5 The Adler−Becker oxidation utilizes stoichiometric sodium metaperiodate (NaIO4), a hypervalent iodine species, to convert 2-(hydroxymethyl)phenols 1, also referred to as salicyl alcohols, into racemic, dearomatized 1-oxaspiro[2.5]-octa-5,7-dien-4-ones 4 (spiroepoxydienones) (Scheme 1a),6 a motif which is readily found in a number of biologically active natural products (Scheme 1c).7 While these oxidation products have been broadly deployed due to their functionalizable dienone motif and proclivity to participate in a variety of cycloaddition reactions,8 the lack of access to enantioenriched spiroepoxydienones limits their applicability.

Scheme 1.

Oxidative Dearomatization of 2-(Hydroxymethyl)phenols

The favorable attributes of the (hydroxymethyl)phenol dearomatization and the interest in enantioenriched spiroepoxydienones led to the development of the hypothesis outlined in Scheme 1b. The reaction design imagines an enabling and underexplored intersection between transient quinone methides and mechanistically validated asymmetric nucleophilic epoxidations using basic H2O2.9

ortho-Quinone methides 2 (oQMs) are dearomatized species that have frequently been employed in forming complex natural products and synthetically useful building blocks.10 A strong driving force for rearomatization underlies the high reactivity of the enone toward [4 + 2]-cycloadditions11 and 1,4-conjugate additions.12 In almost all cases, these transformations irreversibly reset the aromaticity of the resultant system, limiting further complexity-building transformations. Reactions involving oQMs resulting in isolable, dearomatized products are rare.13

Because phenol 1 is formally related to its derived oQM 2 by dehydration, a key challenge to achieving the title process would be the identification of conditions that facilitate dehydrative QM formation under mild conditions: a new method of QM generation was deemed to be a prerequisite for success of the project.14 Scheme 1 moreover postulates that the reaction of a nonstabilized,15 ephemeral QM with H2O2 under basic conditions would initially re-establish aromaticity affording hydroperoxide 3 but concurrently set the stage for heterolytic O−O bond cleavage induced by engagement at the phenolic α-carbon, thereby breaking aromaticity for the second time in the sequence and creating the spiroepoxide substructure (4). Employing an asymmetric ion-pairing phase-transfer catalyst with phenoxide 3 could selectively facilitate the O−O bond cleavage, affording the enantioenriched spiroepoxydienone.

2. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Considering this hypothesis, we converted primary alcohol 1a16 to its unstable monoacetate 5 in low yield. When phenol 5 was subjected to KOH and H2O2 in MeCN at −5 °C, the desired spiroepoxydienone 4a was observed (Table 1, entry 1). Diacetate 6 was prepared in 70% yield and exhibited better stability than 5. Diacetate 6 in turn gave 4a in somewhat higher yield relative to the preparation from the monoacetate 5 (entry 2). The effciency of quinone methide formation could be affected by the rates of both the phenolic deacylation (loss of R1) and expulsion of (−)OR2; the electronic characteristics of both groups should be critical. To accelerate both steps, the more electron-deficient mono- and dichloroacetate analogues were prepared and exhibited drastically improved intermediate and product yields (entries 3 and 4). Bis(trifluoroacetate) 9 performed at a modest level (entry 5); consequently, bis(dichloroacetate) analogue 8 was selected for deployment with additional phenols.17 Dichloroacetate merits some consideration of the molecular mass “sacrificed”, but the attractiveness of this acid chloride as a dehydrating agent stems in no small part from its cheap access on scale, high yields (>90%), and wide applicability and the fact that bis-(dichloroacetates) 8 are stable and often exist as easily handled white solids.

Table 1.

Identification of an Optimal Activating Group for Quinine Methide Formation

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | R1 | R2 | acetate product | yield 5–9 (%)a | yield 4a (%)b | overall yield (%) |

| 1 | H |  |

5 | 40 | 21 | 8 |

| 2 |  |

|

6 | 70 | 37 | 26 |

| 3 |  |

|

7 | 89 | 60 | 54 |

| 4 |  |

|

8 | 95 | 80 | 76 |

| 5 |  |

|

9 | 74 | 55 | 41 |

Isolated yield.

1H NMR yield versus internal standard

Using the optimized racemic conditions identified in Table 1, alkyl-substituted 2-(hydroxymethyl)phenols afforded the highest yields of the desired spiroepoxide products (Table 2, 4a−c, i−k). Alkyl groups promote the formation of QMs while reducing the rate of detrimental dimerization processes.18 Electron-withdrawing substituents are reported to inhibit QM formation18 and lead to oligomerization under basic conditions;19 however, when using difluorophenol 8e, the desired product 4e was obtained (47%). In contrast, difluorophenol 1e failed to provide any discernible product when NaIO4 was used, highlighting the complementary nature of this method relative to the Adler−Becker oxidation. Mixed alkyl and halogen substitution afforded similar yields when 9 equiv of peroxide was used (4f). Because benzylic substitution (R5) often promotes facile rearrangement of spiroepoxydienones to benzodioxoles,5 we used bicyclic substrates 8g−h to prevent rearrangement and observed good yields with excellent diastereoselectivity in 4g.

Table 2.

Racemic Scope of Oxidative Dearomatization Using Bis(dichloroacetates) of 2-(Hydroxymethyl)phenolsa

|

Reactions performed with 1.0 equiv of 8 and 3.0 equiv of both H2O2 and KOH in MeCN ([8]0 = 0.05 M). Yields refer to isolated yields.

4 equiv of KOH was used.

Product isolated as dimer.

Slow addition of a solution of 8 and H2O2 over the course of 1 h.

9 equiv of H2O2 was used.

Determined by 1H NMR spectroscopic analysis.

The substitution pattern around the o-spiroepoxydienone was a critical determinant of whether the product was isolated in monomeric or dimeric form.20 Compounds 4i−l with no substitution at R4 generally favored dimerization upon isolation. Unsubstituted salicyl alcohol 4l afforded the lowest yield and resulted in a multitude of side products (i.e., oligomers, QM dimers). Substrates prone to dimerization required that bis(dichloroacetate) 8 and H2O2 were added over the course of 1 h to reduce excess QM accumulation in solution. Rapid addition (<1 min) of 8 and H2O2 to the KOH/ MeCN mixture resulted in a 1:1 mixture of the dimer and chromane 10, the product of trapping of the spiroepoxydienone with excess QM in solution (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Observed Competition between Product Dimerization and Quinone Methide Trapping

With a mechanistically distinct phenolic oxidation in hand, we became interested in developing an asymmetric variant of the title process. Enantioselective transformations utilizing oQMs lacking methide substitution under basic conditions are limited due to their high reactivity and propensity to dimerize rapidly in solution.21 While asymmetric Weitz−Scheffer-type epoxidations are well established for chalcones and other β-substituted enones using cinchona alkaloid phase-transfer catalysts (PTCs), asymmetric epoxidations of enones lacking β-substitution are rare.22 Employing in situ-generated oQMs that lack substitution at the methide position presents a formidable challenge in controlling the stereochemistry of the resultant spiroepoxide.

Toward this end, we envisioned employing an asymmetric ion-pairing PTC with phenoxide 3 as a method for controlling the facial selectivity of heterolytic O−O bond cleavage, a mechanism closely related to phase-transfer-catalyzed α-enolate substitution reactions.23 Computational analyses of these enantioselective reactions have revealed tight catalyst control of the substrate and electrophile to direct the facial selectivity of the substitution.24 While PTC α-enolate substitution reactions frequently involve the coordination of external electrophiles, more recent examples employ internal electrophiles using cinchona alkaloid PTCs bearing a free hydroxyl group.25

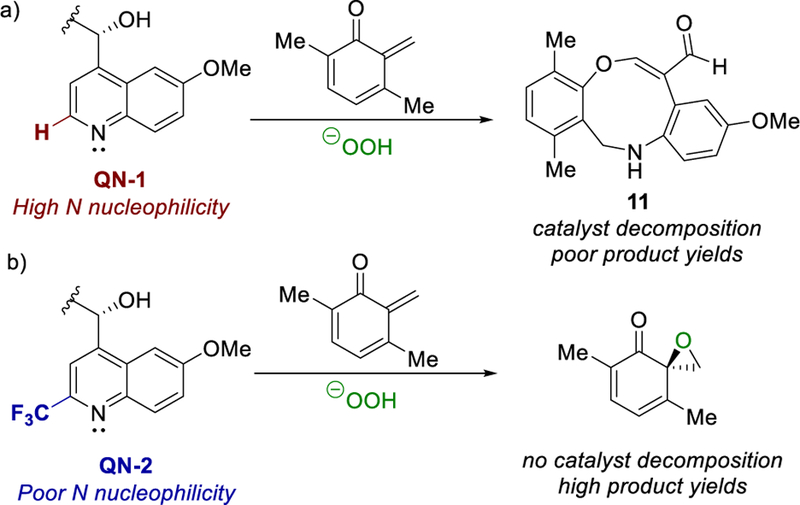

We therefore began our catalyst screening by employing various cinchona alkaloid PTCs with a free hydroxyl group.26 Gratifyingly, phase-transfer catalyst CN-1 with CH2Cl2 solvent using 30% aqueous H2O2 as the oxidant resulted in a 55:45 er (Table 3, entry 1). Further catalyst optimization revealed that more electron-deficient benzyl groups (i.e., CN-3) improved selectivity (entry 3). Employing urea·H2O2 (UHP) to limit water content gave appreciable increases in selectivities and yields. Switching to quinine as the cinchona alkaloid (QN-1) greatly improved the er while affording mediocre yields (entry 4). Cooling the reaction temperature to −20 °C resulted in lower yields and selectivities (entry 5). Dihydroquinine catalyst DHQ-1 was investigated to minimize potential in situ derivatization of the catalyst’s olefin via a Diels−Alder cycloaddition with a transient quinone methide (entry 6). Disappointingly, this catalyst resulted in the same yields and selectivities as QN-1. Upon further analysis, increased catalyst loading resulted in increased side product formation. Characterization revealed putative oxazonine 11 resulting from nucleophilic attack on a generated QM by the catalyst’s quinoline nitrogen followed by cleavage of the quinuclidine core (Scheme 3). To minimize the nucleophilicity of the quinoline nitrogen while simultaneously providing steric hindrance,27 catalyst QN-2 with a trifluoromethyl group was developed (30% yield over 3 steps from quinine N-oxide), which considerably improved yields while maintaining selectivities (entry 7).

Table 3.

Optimization of Enantioselective Oxidative Dearomatizationa

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | cat. | mol % | [O] | T (°C) | era | yield (%)b |

| 1 | CN-1 | 20 | H2O2 (aq) | 0 | 55:45 | <10 |

| 2 | CN-2 | 20 | H2O2 (aq) | 0 | 50:50 | <10 |

| 3 | CN-3 | 20 | H2O2 (aq) | 0 | 63:37 | <10 |

| 4 | CN-3 | 20 | UHP | 0 | 69:31 | 33 |

| 5 | QN-1 | 20 | UHP | 0 | 85:15 | 50 |

| 6 | QN-1 | 20 | UHP | −10 | 87:13 | 55 |

| 7 | QN-1 | 20 | UHP | −20 | 80:20 | 43 |

| 8 | DHQ-1 | 20 | UHP | −10 | 87:13 | 52 |

| 9 | QN-2 | 20 | UHP | −10 | 85:13 | 70 |

| 10 | QN-2 | 20 | UHP | −40 | 87:13 | 85 |

| 11 | QN-2 | 10 | UHP | −40 | 87:13 | 86 |

| ||||||

Reactions were performed using 8a (0.50 mmol), KOH (1.5 mmol), UHP (1.5 mmol), and [8a]0 = 0.05 M in CH2Cl2. 8a was added over the course of 2.5 h.

er was determined by chiral HPLC.

Isolated yields.

Scheme 3.

Preventing Catalyst Decomposition

Using the optimized catalyst and reaction conditions, various bis(dichloroacetates) were evaluated for conversion to their derived enantioenriched epoxides (Table 4). Monomers 4a−d were all found to afford modest selectivities with high yields; however, good to excellent enantioselectivities with good mass recovery could be achieved via a single recrystallization. Similarly, dimer 4i exhibited slightly diminished selectivities that could be upgraded by a single recrystallization, affording excellent selectivities and modest recovery. It was quickly apparent that the stability and substitution pattern of the generated QM were important factors in determining the yield and enantioselectivities of the reaction. Attempts to access the enantioenriched unsubstituted dimer 4l resulted in low yields of the racemic dimer due to rapid QM oligomerization relative to epoxidation under the basic conditions. In contrast, bicyclic substrate 4h gave excellent yields but afforded poor selectivity, although a change in the enantiodetermining step of the reaction should be noted with these β-substituted substrates.

Table 4.

|

Reactions were performed using 8 (0.50 mmol), QN-2 (10 mol %), KOH (1.5 mmol), UHP (1.5 mmol), and [8] = 0.05 M in CH2Cl2, at −40 °C.

er was determined by chiral HPLC.

Values in parentheses represent recrystallized yields and enantiomeric ratios.

20 mol % QN-2.

An evaluation of the reaction mechanism was initiated by comparing the stereochemical outcome of the H2O2-mediated oxidative dearomatization of 1g to that when NaIO4 was employed (Scheme 4a). NaIO4 oxidation proceeded with stereoretention (12), while Weitz−Scheffer epoxidation9 of the planar QM intermediate proceeded with highly diastereoselective inversion at the benzylic position (4g). Based upon this observation, we propose the initial deacylation of the phenolic dichloroacetate 8a to afford phenoxide A followed by formation of oQM B via elimination of the benzylic dichloroacetate. Conjugate addition by hydroperoxide affords the rearomatized phenoxide C that attacks the hydroperoxide to give the dearomatized epoxide 4a (Scheme 4b).

Scheme 4.

Mechanistic Insights and Proposed Mechanism

The unique and critical role of PTC QN-2 in both QM generation and stereoselective epoxide formation is evident in this mechanism. To further understand the catalyst’s role in promoting the observed stereoselectivity, the transition state of the epoxidation step between QN-2 and 3a was studied computationally using density functional theory (DFT) calculations at the level of M062X28a approximate functional and a compound Pople basis set.28b,c

Upon analysis of the calculated major stereoisomer (Figure 1a), several important interactions emerge: (a) the hydroxide nucleofuge is stabilized by two significant hydrogen bonding interactions derived from the Ar−H on the electron-deficient (CF3)2Ar ring (H···O distance 2.06 Å) and the benzylic C−H in close proximity to the ammonium cation (H···O distance 2.16 Å) as well as a weaker hydrogen bonding interaction from the C−H bond on the bridged quinuclidine (H···O distance 2.67 Å);29 (b) the catalyst −OH group forms a strong hydrogen bond (H···O distance 1.83 Å) to the phenoxide of the substrate, orienting the hydroperoxide in close proximity to the three stabilizing hydrogen bond donors; and (c) the C-2 methyl group on 3a experiences an attractive CH−π interaction with the quinoline ring (atom to plane distance of 2.50 Å).30 The apparent synergistic role of the R N+CH −cationic subunits and the (F C) Ar−H is to create an unconventional trifurcated oxyanion hole to stabilize and accommodate the nascent alkoxide during O−O scission (vide infra). Such interactions for nucleofuge stabilization have been previously identified via DFT calculations but arise principally or solely from the R3N+CH2−cationic subunit.24

Figure 1.

DFT-optimized stereodetermining transition states of QN-2 and 3a.

We were interested in comparing the stereodetermining catalyst−substrate interactions leading to the formation of the minor enantiomer to those leading to major isomer formation. These interactions were calculated to be similar to the major isomer (Figure 1b), with the distinction being a ∼90° rotation of the substrate’s aromatic ring to afford the opposite epoxide facial selectivity. The transition state leading to minor enantiomer formation was calculated to be 0.84 kcal/mol greater in energy than the major enantiomer. This higher energy transition state can be explained by (a) the loss of the attractive CH−π interaction between the substrate C-2 methyl group and the quinoline ring and (b) the observed lengthening of the hydrogen bonding interaction between the hydroxide nucleofuge and the benzylic C−H (2.36 Å versus 2.16 Å), mitigating, in part, the stabilization of the leaving group. The increased transition state barrier due to the loss of the methyl CH−π interaction is in accord with experimental evidence demonstrating reduced enantiocontrol with lack of alkyl substitution.

1-Oxaspiro[2.5]octa-5,7-dien-4-ones (4) are highly reactive species which readily participate in Michael additions,31 dihydroxylation,31 epoxide openings,32 and cycloadditions.33 To further highlight the synthetic utility of this reaction in complexity building transformations, enantioenriched spiroepoxydienone generation was merged with subsequent base-promoted acyl-nitroso generation from 1334 to realize a one-pot oxidative dearomatization/acyl-nitroso Diels−Alder cyclo-addition. The derived tricyclic oxazinanone 14 (Scheme 5) was obtained with excellent enantio- and diastereoselectivity after a single recrystallization. These tricyclic oxazinanones can be further elaborated to afford highly substituted cyclohexanone rings in a short number of synthetic steps.5

Scheme 5.

One-Pot Enantioselective Oxidative Dearomatization/Acyl-Nitroso Diels−Alder Cycloaddition

3. CONCLUSION

We have developed an enantioselective oxidative dearomatization of 2-(hydroxymethyl)phenols using H2O2 to afford stable, dearomatized 1-oxaspiro[2.5]octadienones employing a base-promoted in situQM activation technique. This reaction highlights the use of a mild and convenient oxidant to afford synthetically useful, dearomatized spiroepoxydienones. By using a new cinchona alkaloid-derived phase-transfer catalyst, the reaction allows for access to enantioenriched o-spiroepoxydienones which were previously inaccessible via the Adler−Becker oxidation. DFT calculations revealed a highly organized transition state involving a unique tripartite stabilization of the hydroxide leaving group leading to the observed facial selectivity. The synthetic utility of this method for rapid complexity generation has been demonstrated by preparing an enantioenriched tricyclic oxazinanone. This chemistry demonstrates the potential for complementary enantioselective dearomative processes involving quinone methides, and our laboratory is currently exploring these possibilities.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The project described was supported by Award R35 GM118055 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. M.F.M. gratefully acknowledges an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship. We thank Dr. Brandie Ehrmann (UNC Mass Spectrometry Core Laboratory) for assistance with mass spectrometry experiments on instrumentation acquired through the NSF MRI program under Award CHE-1726291. We also thank the UNC Research Computing Center for access to its facilities to perform the DFT calculations. Professor Marcey Waters (UNC), Dr. Steffen Good (UNC), and Dr. Samuel Bartlett (UNC) are acknowledged for helpful discussions. X-ray crystallography was performed by Dr. Blane Zavesky (UNC).

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/jacs.8b13006.

CIF file giving data for compound 4i (CIF)

Experimental procedures, characterization, and spectral data for all new chemical compounds as well as crystal data and data collection parameters (PDF)

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).(a) Vo NT; Pace RDM; O’Har F; Gaunt M An Enantioselective Organocatalytic Oxidative Dearomatization Strategy. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jackson SK; Wu K; Pettus TRR Sequential Reactions Initiated by Oxidative Dearomatization. Biomimicry or Artifact? In Biomimetic Organic Synthesis; Poupon E, Nay B, Ed.; Wiley-VCH Verlag & Co: Weinheim, Germany, 2011; pp 723–749. [Google Scholar]; (c) Roche SP; Porco JA Dearomatization Strategies in the Synthesis of Complex Natural Products. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2011, 50, 4068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).(a) Varvoglis A Hypervalent Iodine in Organic Synthesis; Academic Press, Inc: San Diego, CA, 1997. [Google Scholar]; (b) Feldman KS Cyclization Pathways of a (Z)-Stilbene-Derived Bis(orthoquinone monoketal). J. Org. Chem 1997, 62, 4983. [Google Scholar]; (c) Tchounwou PB; Yedjou CG; Patolla AK; Sutton DJ Heavy metal toxicity and the environment. EXS 2012, 101, 133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Dong S; Zhu J; Porco JA Enantioselective Synthesis of Bicyclo[2.2.2]octenones Using a Copper-Mediated Oxidative Dearomatization/[4 + 2] Dimerization Cascade. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 2738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).(a) Goti A; Cardona F Hydrogen Peroxide in Green Oxidation Reactions: Recent Catalytic Processes. In Green Chemical Reactions; Tundo P, Esposito V, Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp 191–212. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tsuji T; Zaoputra AA; Hitomi Y; Mieda K; Ogura T; Shiota Y; Yoshizawa K; Sato H; Kodera M Specific Enhancement of Catalytic Activity by a Dicopper Core: Selective Hydroxylation of Benzene to Phenol with Hydrogen Peroxide. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2017, 56, 7779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Good SN; Sharpe RJ; Johnson JS Highly Functionalized Tricyclic Oxazinanones via Pairwise Oxidative Dearomatization and N-Hydroxycarbamate Dehydrogenation: Molecular Diversity Inspired by Tetrodotoxin. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 12422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).(a) Adler E; Brasen S; Miyake H Periodate Oxidation of Phenols. IX. Oxidation of o-(omega-Hydroxyalkyl)phenols. Acta Chem. Scand 1971, 25, 2055. [Google Scholar]; (b) See the Supporting Information for a photochemical stability study of o-spiroepoxydienones. [Google Scholar]

- (7).(a) Bruno M; Omar AA; Perales A; Piozzi F; Rodriguez B; Savona G; de la Torre MC Neo-clerodane diterpenoids from Teucrium oliverianum. Phytochemistry 1991, 30, 275. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kupchan SM; Court WA; Dailey RG Jr.; Gilmore CJ; Bryan RF Tumor inhibitors. LXXIV. Triptolide and tripdiolide, novel antileukemic diterpenoid triepoxides from Tripterygium wilfordii. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1972, 94, 7194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Sperry S; Samuels GJ; Crews P Vertinoid Polyketides from the Saltwater Culture of the Fungus Trichoderma longibrachiatum Separated from a Haliclona Marine Sponge. J. Org. Chem 1998, 63, 10011. [Google Scholar]

- (8).(a) Corey EJ; Dittami JP Total synthesis of (±)-ovalicin. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1985, 107, 256. [Google Scholar]; (b) Shair MD; Danishefsky SJ Observations in the Chemistry and Biology of Cyclic Enediyne Antibiotics: Total Syntheses of Calicheamicin γ1I and Dynemicin A. J. Org. Chem 1996, 61, 16. [Google Scholar]; (c) Singh V Spiroepoxycyclohexa-2,4-dienones in Organic Synthesis. Acc. Chem. Res 1999, 32, 324. [Google Scholar]; (d) Yang D; Ye X; Xu M Enantioselective Total Synthesis of (−)-Triptolide, (−)-Triptonide, (+)-Triptophenolide, and (+)-Triptoquinonide. J. Org. Chem 2000, 65, 2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Weitz E; Scheffer A Über die Einwirkung von alkalischem Wasserstoffsuperoxyd auf ungesaẗtigte Verbindungen. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. B 1921, 54, 2327. [Google Scholar]

- (10).For excellent reviews on QMs, see:; (a) Willis NJ; Bray CD ortho-Quinone Methides in Natural Product Synthesis. Chem. - Eur. J 2012, 18, 9160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bai W; David JG; Feng Z; Weaver M; Wu K; Pettus TRR The Domestication of ortho-Quinone Methides. Acc. Chem. Res 2014, 47, 3655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Caruana L; Fochi M; Bernardi L The Emergence of Quinone Methides in Asymmetric Organo-catalysis. Molecules 2015, 20, 11733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Singh MS; Nagaraju A; Anand N; Chowdhury S ortho-Quinone methide (o-QM): a highly reactive, ephemeral and versatile intermediate in organic synthesis. RSC Adv 2014, 4, 55924. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Spence JTJ; George JH Total Synthesis of Peniphenones A−D via Biomimetic Reactions of a Common o-Quinone Methide Intermediate. Org. Lett 2015, 17, 5970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Guo W; Wu B; Zhou X; Chen P; Wang X; Zhou Y; Liu Y; Li C Formal Asymmetric Catalytic Thiolation with a Bifunctional Catalyst at a Water−Oil Interface: Synthesis of Benzyl Thiols. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2015, 54, 4522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).For examples of nucleophilic addition to stable pQMs resulting in dearomatized products, see:; (a) Yuan Z; Fang X; Wu J; Hequan Y; Lin A 1,6-Conjugated Addition-Mediated [2 + 1] Annulation: Approach to Spiro[2.5]octa-4,7-dien-6-one. J. Org. Chem 2015, 80, 11123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ma C; Huang Y; Zhao Y Stereoselective 1,6-Conjugate Addition/Annulation of para-Quinone Methides with Vinyl Epoxides/Cyclopropanes. ACS Catal 2016, 6, 6408. [Google Scholar]; (c) Roiser L; Waser M Enantioselective Spirocyclopropanation of para-Quinone Methides Using Ammonium Ylides. Org. Lett 2017, 19, 2338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).(a) Toteva MM; Richard JP The Generation and Reactions of Quinone Methides. Adv. Phys. Org. Chem 2011, 45, 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jaworski AA; Scheidt KA Emerging Roles of in Situ Generated Quinone Methides in Metal-Free Catalysis. J. Org. Chem 2016, 81, 10145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Jurd L Quinones and quinone-methides I: Cyclization and dimerisation of crystalline ortho-quinone methides from phenol oxidation reactions. Tetrahedron 1977, 33, 163. [Google Scholar]

- (16).Due to the propensity of spiroepoxydienones to dimerize,6,20 3,6-dimethylsalicyl alcohol (1) was selected as a model substrate since dimerization of 4a is slow and the monomer is stable for long periods.5

- (17). See the Supporting Information for detailed optimization of the racemic oxidative dearomatization reaction.

- (18).Weinert EE; Dondi R; Colloredo-Melz S; Frankenfield KN; Mitchell CH; Freccero M; Rokita SE Substituents on Quinone Methides Strongly Modulate Formation and Stability of Their Nucleophilic Adducts. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 11940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).(a) Wan P; Hennig D Photocondensation of o-hydroxybenzyl alcohol in an alkaline medium: synthesis of phenol−formaldehyde resins. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun 1987, 939. [Google Scholar]; (b) Chiang Y; Kresge AJ; Zhu Y Flash Photolytic Generation of ortho-Quinone Methide in Aqueous Solution and Study of Its Chemistry in that Medium. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2001, 123, 8089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).For structural orientation of dimers, see:; (a) Adler E; Holmberg K; et al. Periodate Oxidation of Phenols. X. Structural and Steric Orientation in the Diels-Alder Dimerization of o-Quinols. Acta Chem. Scand 1971, 25, 2775. [Google Scholar]; (b) Adler E; Holmberg K; et al. Diels-Alder Reactions of 2,4-Cyclohexadienones. I. Structural and Steric Orientation in the Dimerisation of 2,4-Cyclohexadienones. Acta Chem. Scand 1974, 28b, 465. [Google Scholar]

- (21).For excellent examples of base-promoted asymmetric reactions involving oQMs lacking methide substitution, see:; (a) Izquierdo J; Orue A; Scheidt KA A Dual Lewis Base Activation Strategy for Enantioselective Carbene-Catalyzed Annulations. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 10634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lee A; Scheidt KA N-Heterocyclic carbene-catalyzed enantioselective annulations: a dual activation strategy for a formal [4 + 2] addition for dihydrocoumarins. Chem. Commun 2015, 51, 3407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Zhu Y; Zhang L; Luo S Asymmetric Retro-Claisen Reaction by Chiral Primary Amine Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 3978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Kelly DR; Caroff E; Flood RW; Heal W; Roberts SM The isomerisation of (Z)-3-[2H1]-phenylprop-2-enone as a measure of the rate of hydroperoxide addition in Weitz−Scheffer and Juliá−Colonna epoxidations. Chem. Commun 2004, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).(a) Dolling UH; Davis P; Grabowski EJJ Efficient catalytic asymmetric alkylations. 1. Enantioselective synthesis of (+)-indacrinone via chiral phase-transfer catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1984, 106, 446. [Google Scholar]; (b) Corey EJ; Xu F; Noe MC A Rational Approach to Catalytic Enantioselective Enolate Alkylation Using a Structurally Rigidified and Defined Chiral Quaternary Ammonium Salt under Phase Transfer Conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1997, 119, 12414. [Google Scholar]; (c) Poulsen TB; Bernardi L; Aleman J; Overgaard J; Jorgensen KA Organocatalytic Asymmetric Direct α-Alkynylation of Cyclic β-Ketoesters. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).(a) de Frietas Martins E; Pliego JR Jr, Unraveling the Mechanism of the Cinchoninium Ion Asymmetric Phase-Transfer-Catalyzed Alkylation Reaction. ACS Catal 2013, 3, 613. [Google Scholar]; (b) He CQ; Simon A; Lam Y-H; Brunskill APJ; Yasuda N; Tan J; Hyde AM; Sherer EC; Houk KN Model for the Enantioselectivity of Asymmetric Intramolecular Alkylations by Bis-Quaternized Cinchona Alkaloid-Derived Catalysts. J. Org. Chem 2017, 82, 8645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).(a) Belyk KM; Xiang B; Bulger PG; Leonard WR Jr; Balsells J; Yin J; Chen C Enantioselective Synthesis of (1R,2S)-1-Amino-2-vinylcyclopropanecarboxylic Acid Ethyl Ester (Vinyl-ACCA-OEt) by Asymmetric Phase-Transfer Catalyzed Cyclopropanation of (E)-N-Phenylmethyleneglycine Ethyl Ester. Org. Process Res. Dev 2010, 14, 692. [Google Scholar]; (b) Xiang B; Belyk KM; Reamer RA; Yasuda N Discovery and Application of Doubly Quaternized Cinchona-Alkaloid-Based Phase-Transfer Catalysts. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2014, 53, 8375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Cullen LR; Denmark SE Development of a Phase-Transfer-Catalyzed, [2,3]-Wittig Rearrangement. J. Org. Chem 2015, 80, 11818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26). See the Supporting Information for a detailed optimization of the enantioselective dearomatization reaction.

- (27).(a) Johansson CCC; Bremeyer N; Ley SV; Owen DR; Smith SC; Gaunt MJ Enantioselective Catalytic Intramolecular Cyclopropanation using Modified Cinchona Alkaloid Organocatalysts. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2006, 45, 6024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Attempts to only sterically inhibit rather than electronically deactivate the quinoline nitrogen by placing a phenyl group at the quinoline 2-position reduced the presence of 11 but failed to improve the yields.

- (28).(a) Zhao Y; Truhlar DG The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Acc 2008, 120, 215. [Google Scholar]; (b) Krishnan R; Binkley JS; Seeger R; Pople JA Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. XX. A basis set for correlated wave functions. J. Chem. Phys 1980, 72, 650. [Google Scholar]; (c) Rassolov VA; Ratner MA; Pople JA; Redfern PC; Curtiss LA 6–31G* basis set for third-row atoms. J. Comput. Chem 2001, 22, 976. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Jeffery GA An Introduction to Hydrogen Bonding; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Carroll WR; Zhao C; Smith MD; Pellechia PJ; Shimizu KD A Molecular Balance for Measuring Aliphatic CH−π Interactions. Org. Lett 2011, 13, 4320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Liotta DC Branched Diepoxide Compounds for the Treatment of Inflammatory Disorders. U.S. Patent 20,100,324,133, December 23, 2010.

- (32).Cacioli P; Reiss JA Reactions of 1-Oxaspiro[2.5]octa-5,7-dien-4-ones with nucleophiles. Aust. J. Chem 1984, 37, 2525. [Google Scholar]

- (33).(a) Singh V; Lahiri S; Kane V; Stey T; Stalke D Efficient Stereoselective Synthesis of Novel Steroid−Polyquinane Hybrids. Org. Lett 2003, 5, 2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Singh V; Chandra G; Mobin S Aromatics to Diquinanes: An Expeditious Synthesis of Tetramethylbicyclo[3.3.0]octane Framework of Ptychanolide. Synlett 2008, 2008, 3111. [Google Scholar]; (c) Jarhad D; Singh V π4s + π2s Cycloaddition of Spiroepoxycyclohexa-2,4-dienone, Radical Cyclization, and Oxidation−Aldol−Oxidation Cascade: Synthesis of BCDE Ring of Atropurpuran. J. Org. Chem 2016, 81, 4304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Sutton AD; Williamson M; Weismiller H; Toscano JP Optimization of HNO Production from N,O-bis-Acylated Hydroxylamine Derivatives. Org. Lett 2012, 14, 472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.