In principle, humans can make an antibody response to any non-self-antigen molecule in the appropriate context. This is achieved by a large naïve antibody repertoire whose diversity is expanded by somatic hypermutation (SHM) following antigen exposure.1 The diversity of the naive human antibody repertoire is estimated to be at least 1012 unique antibodies.2 Since the number of peripheral blood B cells in an healthy adult human is on the order of 5×109, the circulating B cell population samples only a small fraction of this diversity. Full-scale analyses of human antibody repertoires have been prohibitively difficult, primarily due to their massive size. The amount of information encoded by all the rearranged antibody and T cell receptor genes in one person -- the “genome” of the adaptive immune system -- exceeds the size of the human genome by more than four orders of magnitude. Further, because much of the B lymphocyte population is localized in organs or tissues that cannot be comprehensively sampled from living subjects, human repertoire studies have focused on circulating B cells.3 Here, we examine the circulating B cell populations of ten human subjects and present the largest single collection of adaptive immune receptor sequences described to date, comprising almost 3 billion antibody heavy chain sequences. This dataset allows genetic study of the baseline human antibody repertoire at unprecedented depth and granularity, revealing largely unique repertoires for each individual studied, a subpopulation of universally shared antibody clonotypes, and exceptional overall repertoire diversity.

Eighteen sequencing libraries were generated for each of ten subjects (Figure ED1). These libraries yielded 2.90×109 raw reads. Following annotation,4 which included duplicate removal using unique molecular identifiers,5 we obtained 3.64×108 productive antibody sequences (Table ED1).

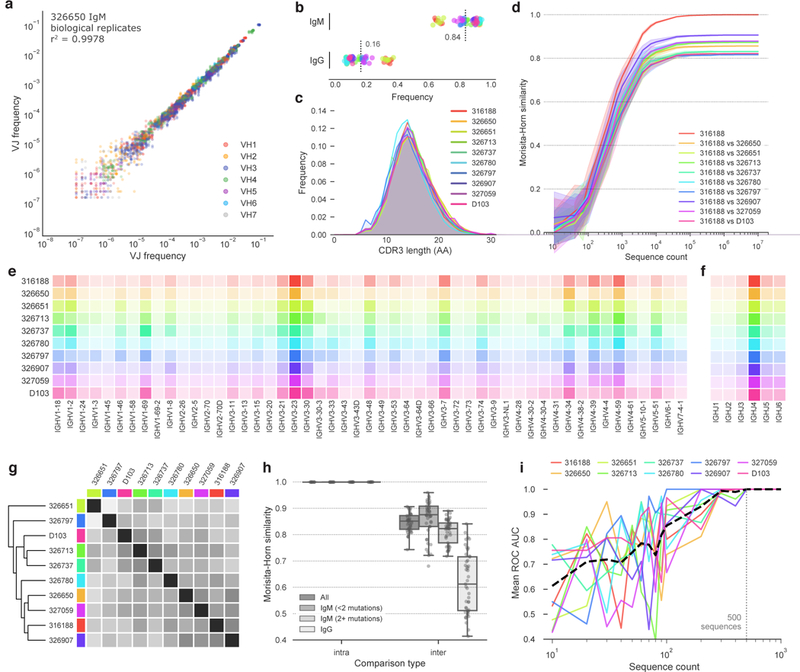

Amplification was reproducible, with similar gene usage between replicates (Figures 1A, ED2). The frequencies of IgM-encoding (0.62–0.94) and IgG-encoding (0.06–0.38) sequences were consistent with the expected frequency of circulating B cells expressing these isotypes (Figure 1B).6 Although V-gene, J-gene and CDRH3 length (VJ-CDR3len) distributions were similar between subjects (Figures 1C, E-F), differences were large enough that individual repertoires could conceivably be distinguished using only these features. We reduced sequence subsamples to VJ-CDR3len frequency distributions and quantified similarity using the Morisita-Horn similarity index.7,8 Subject repertoires were clearly distinguishable using as few as 104 sequences (Figures 1D, ED4) and did not cluster by age, gender or ethnicity (Figure 1G). The IgG+ repertoires were least similar, suggesting that subjects’ unique immunological histories are a significant contributor to repertoire individuality (Figure 1H). A one-versus-rest support vector machine (SVM) classifier trained on VJ-CDR3len data from 5 of the 6 biological replicates from each subject accurately assigned the remaining replicate using test/train datasets of as few as 500 sequences from each replicate (Figure 1I).

Figure 1. Uniqueness of the repertoires of individual subjects.

a) Frequency comparison of V/J combinations in biological replicates from subject 326650. V/J combinations are colored according to the V-gene used. b) Sequence frequency by antibody isotype. Subjects are colored as in (c). Each point represents a single biological replicate. Mean of all samples is indicated for each isotype. c) CDRH3 length distribution for each subject. CDRH3 lengths were determined using the IMGT numbering scheme. d) Morisita-Horn similarity of pairwise comparisons between subject 316188 and each of the other subjects. Lines indicate mean similarity of 20 bootstrap samplings and shaded areas indicate 95% confidence intervals. Data from subject 316188 is representative; plots for all other subjects can be found in Figure ED4. V-gene (e) and J-gene (f) use by subject. Increased color intensity indicates higher frequency. Subjects are colored as in (c). g) Clustered distance matrix of subjects, using pairwise VJ-CDR3len Morisita-Horn similarity as the distance measure. Distance matrix was computed using single-linkage clustering (Euclidean distance metric). Subject colors are as in (c). A dendrogram representation of the distance matrix is also shown on the left side of the distance matrix. h) Comparison of intra- and inter-subject VJ-CDR3len similarity, using either all sequences, IgM sequences with fewer than two nucleotide mutations, IgM sequences with two or more mutations, or IgG sequences. Points represent individual intra- or inter-subject comparisons. Boxplots show the median line and span the 25th-75th percentile, with whiskers indicating the 95% confidence interval. i) Mean receiver operating characteristic (ROC) area under the curve (AUC) for a one-versus-rest SVM classifier. The ROC AUC does not drop below 1.0 for any subject when the test/training datasets include ≥500 sequences each, and that threshold is indicated with a dashed vertical line.

To estimate repertoire diversity while minimizing the effects of sequencing and amplification error, we first considered clonotype diversity. An antibody clonotype is a collection of sequences using the same V/J-genes and encoding an identical CDRH3 amino acid sequence.9 For each subject, all sequences from each biological replicate were collapsed into a set of unique clonotypes. Any clonotypes repeatedly observed after pooling deduplicated biological replicates must be derived from different cells, providing a straightforward means of quantifying multiple occurrence. For clarity, clonotypes or sequences present in multiple biological replicates from a single subject will be called “repeatedly observed”, while clonotypes or sequences found in multiple subjects will be called “shared”.

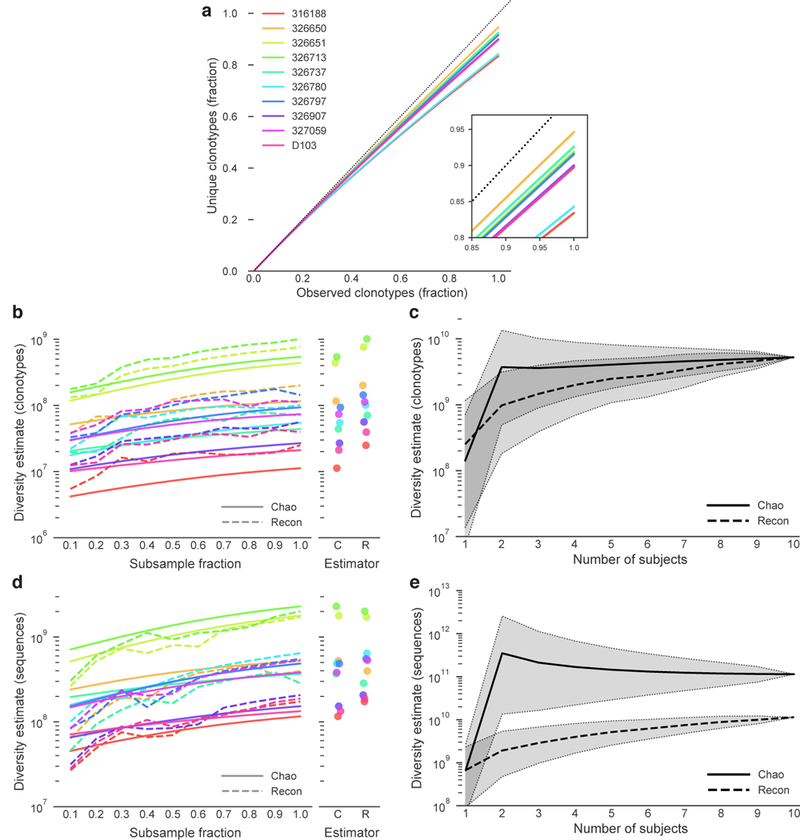

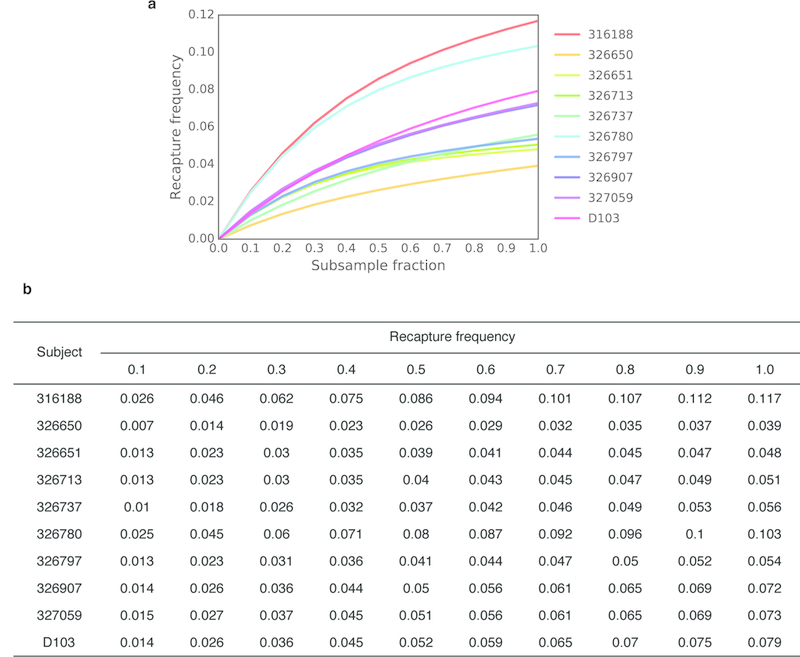

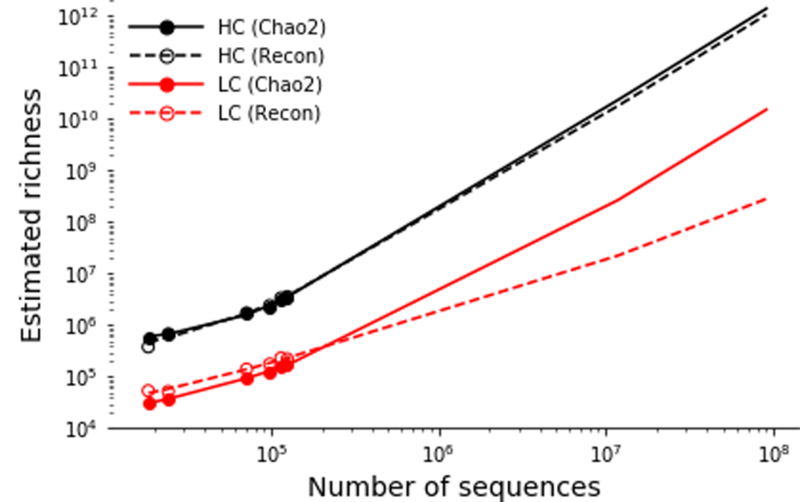

Rarefaction curves indicated a low frequency of repeatedly observed clonotypes, supported by capture-recapture sampling (3.9–11.7% recapture; Figure 2A, ED6). To estimate repertoire diversity, we selected two estimators: Chao2 and Recon. Chao2 is a non-parametric estimator that uses repeat occurrence data from multiple samples to estimate species richness.10 Recon uses maximum likelihood to estimate species richness, assuming only that the overall size of the repertoire is large (relative to sampling depth) and well mixed.11 These estimates represent the total diversity capable of being generated by the humoral immune system. Accordingly, these estimates may greatly exceed the actual number of B cells present in a single individual at any one time. The estimators produced similar estimates of clonotype diversity for each subject, with identical rank order (Figure 2B). Recon consistently estimated about 2-fold greater repertoire diversity (2×107-1×109) than Chao2 (1×107-5×108), consistent with reports that Chao2 underestimates richness for samples with a non-negligible frequency of rare species.12,13 Pooling unique clonotypes from multiple subjects allowed us to estimate cohort-wide diversity (Figure 2C). Chao2 (5×109) and Recon (5×109) produced nearly identical estimates for the complete 10-subject pool. Estimates of cohort-wide clonotype diversity exceed individual subject estimates by less than two orders of magnitude, suggesting a relatively high frequency of shared clonotypes. We next sought to estimate the sequence diversity for each individual, again using both Chao2 and Recon estimators. As expected, the estimates for sequences were substantially higher than for clonotypes, with Chao2 (2×108-2×109) and Recon (1×108-2×109) producing comparable estimates for each subject. Unlike the cohort-wide clonotype estimates, Recon estimated much lower cohort-wide sequence diversity (1×1010) than Chao2 (1×1011; Figure 2E). The light chain repertoire is estimated to be approximately four orders of magnitude less diverse than the heavy chain repertoire (Figure ED7) and pairing of heavy and light chains is approximately random,14 producing a total paired sequence diversity estimate of 1016 to 1018. The most commonly cited estimate for antibody repertoire diversity, 1012 unique sequences,2 considers only the unmutated naïve repertoire. As such, our sequence diversity estimates, which include both the naïve and memory sequences, are not directly comparable to this previous estimate. Clonotype diversity estimates, which incorporate only V and J gene assignments and the CDRH3 amino acid sequence, minimize the influence of SHM and are more suitable for comparison with prior estimates of naïve repertoire diversity. The cohort-wide paired clonotype diversity using either estimator, under the same assumptions about light chain diversity and random pairing, is estimated at 3×1015, over three orders of magnitude greater than previously estimated for the naïve repertoire.

Figure 2. Clonotype and sequence diversity amongst the 10 subjects.

a) Clonotype rarefaction curves for each subject. Lines represent the mean of 10 independent samplings, with the exception of the 1.0 fraction, which was sampled once. The dashed line represents a perfectly diverse sample. Inset is a close-up of the rarefaction curve ends. b) Total clonotype repertoire diversity estimates were computed for increasingly large fractions of each subject’s clonotype repertoire. Each line represents the mean of 10 random sub-samplings without replacement (again, except for the 1.0 fraction). Chao estimates are shown in solid lines, Recon estimates are shown in dashed lines. Subject colors are as in (a). Maximum diversity (1.0 fraction of each subject) for each estimator is shown in the right panel. c) Overall cross-subject clonotype diversity of each possible combination of 1 or more subjects. The Chao estimate is a solid line and the Recon estimate is a dashed line. Shaded regions indicate 95% confidence intervals. The confidence intervals in (c) are for different groupings of subjects, not for the estimators themselves. d) Total sequence repertoire diversity estimates were computed for increasingly large fractions of each subject’s sequence repertoire. Each line represents the mean of 10 random sub-samplings without replacement (except for the 1.0 fraction, for which only a single calculation was made). Chao estimates are shown in solid lines, Recon estimates are shown in dashed lines. Subject colors are as in (a). Maximum diversity (1.0 fraction of each subject repertoire) for each estimator is shown in the right panel. e) Overall cross-subject nucleotide sequence diversity of each possible combination of 1 or more subjects. The Chao estimate is a solid line and the Recon estimate is a dashed line. Shaded regions indicate 95% confidence intervals. Confidence intervals are as in (c).

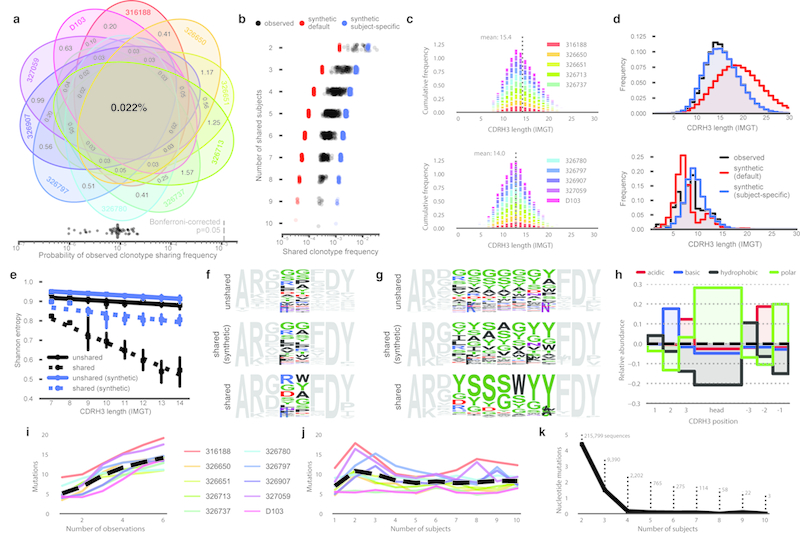

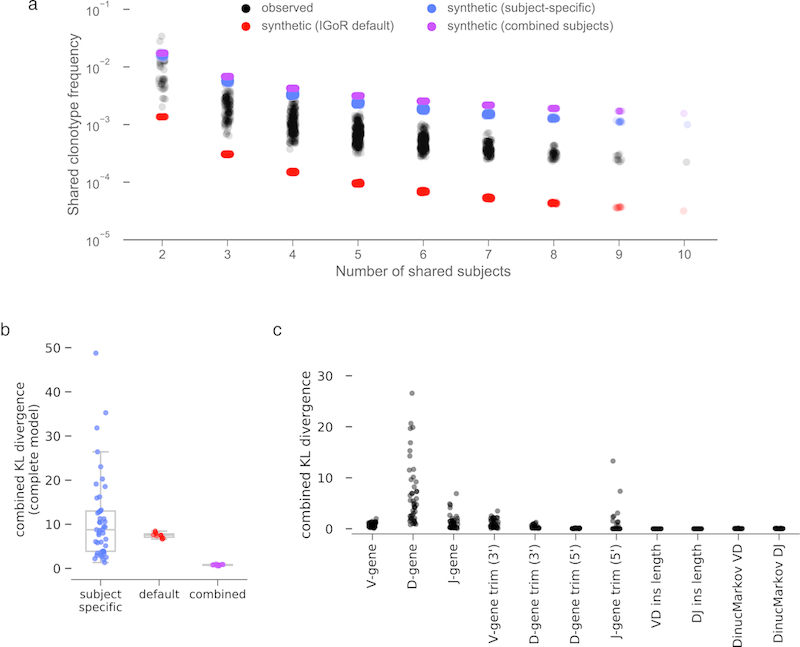

While it is known that convergent antibodies may arise from different individuals in response to immunological exposure and a low frequency of CDRH3 sharing has been observed in healthy adult repertoires,9,15 the overall prevalence of repertoire sharing is unknown. For each combination of two or more subjects, we computed the frequency of shared clonotypes (Figure 3A). Pairs of subjects shared, on average, 0.95% of their respective clonotypes and 0.022% of clonotypes were shared by all ten subjects. We next used two approaches to quantify the expected frequency of clonotype sharing by chance. Hypergeometric distributions, based on cohort-wide clonotype diversity (Chao2) and the number of unique clonotypes for each subject, indicated a low likelihood that the observed sharing was due to chance (8.8×10−6, Bonferroni-corrected p=0.05 is 1.1×10−3). We also generated synthetic antibody sequences using IGoR16 to determine the expected frequency of clonotype sharing due to coincident V(D)J recombination. Synthetic sequence sets were generated using three different recombination models: 1) IGoR’s default model, inferred from unproductive antibody rearrangements and is thus focused only on parameters related to V(D)J recombination; 2) subject-specific recombination models inferred from unmutated sequences from each subject; and 3) a combined-subject recombination model inferred from a pool of unmutated sequences drawn from all subjects. For each model, 10 batches of 108 sequences were generated, for a total of 3 billion synthetic sequences. In the sequence sets generated with IGoR’s default model, clonotype sharing was 7-fold lower than in human repertoires (0.0032%; Figure 3B) indicating that coincident V(D)J recombination alone is not sufficient to explain the observed sharing. The subject-derived synthetic sequence sets showed much more sharing (0.1% and 0.16%, respectively; Figure 3B, ED8). In addition to containing information about V(D)J recombination, the subject-derived models also implicitly encode information about selection processes involved in B cell development. The increased clonotype sharing frequency in subject-derived synthetic datasets indicates that the sieving effect of B cell development produces naive repertoires that are more similar than recombination alone would be expected to produce. Combined with our observation that naive-enriched repertoires are more similar than class-switched repertoires (Figure 1H), a model emerges in which individual repertoires are quite dissimilar after V(D)J recombination, are homogenized during B cell development, and become increasingly individualized following differential responses to immunological exposure.

Figure 3. Shared clonotypes and sequences amongst the 10 subjects.

a) Venn diagram of shared clonotype frequency. b) Shared clonotype frequency between subject groups. Points represent different group combinations. Observed sequences (black), synthetic sequences generated with IGoR’s default model (red), and sequences generated with subject-specific models (blue) are shown. c) CDRH3 length distribution of clonotypes found in one biological replicate (top) or all six biological replicates (bottom). CDRH3 length is defined using IMGT numbering. The legend was split maintain legibility; data for all subjects is present in both plots. d) CDRH3 length distribution of unshared clonotypes (top) or clonotypes shared by the majority of subjects (bottom). Observed sequences (black), default model (red) and subject-specific model (blue) synthetic sequences are shown. e) Per-position Shannon entropy of the CDRH3 head regions of unshared (solid) or majority-shared (dashed) clonotypes. Points indicate the mean, whiskers indicate the 95% confidence interval, and lines represent the linear best fit. f-g) Sequence logos of the CDRH3s encoded by observed unshared clonotypes, observed majority-shared clonotypes, and synthetic majority-shared clonotypes of length 8 (f) or 13 (g). Head region amino acid coloring: polar amino acids (GSTYCQN) are green, basic (KRH) blue, acidic (DE) red, and hydrophobic (AVLIPWFM) black. All torso residues are grey. h) Relative abundance of amino acid properties in the CDRH3s of majority-shared clonotypes. Abundances are normalized to the frequency in unshared clonotypes. i) Nucleotide mutations for singly observed or repeatedly observed clonotypes. Colored lines indicate the mean for each subject, the dashed black line indicates the mean of all subjects. j) Nucleotide mutations for shared or unshared clonotypes. Colored lines indicate the mean for each subject, the dashed black line indicates the mean of all subjects. k) Mutation frequency of nucleotide sequences shared by two or more subjects. Points indicate mean mutation frequency. The number of unique nucleotide sequences in each shared group is shown.

While the CDRH3 length distributions of unique and repeatedly observed clonotypes were similar, short CDRH3s were much more common in shared clonotypes (Figure 3C-D). The skew toward short CDRH3s in the shared population is likely due to the increased probability of similar recombination events among shorter CDRH3s. In contrast, repeatedly observed clonotypes are more often the result of clonal expansion, as evidenced their increased mutation frequency (Figure 3I). Shared nucleotide sequences showed a strong inverse relationship between mutation frequency and the number of shared subjects (Figure 3K); virtually all sequences shared by 4 or more subjects were unmutated. Thus, while coincident recombination infrequently produces identical antibody sequences, the likelihood of coincident recombination linked to an identical set of somatic mutations is exceptionally low.

Antibody CDRH3s can be divided into two primary regions: the framework-proximal “torso” and the more variable “head”.17,18 When comparing size-matched samples of shared and unshared clonotypes, we noted less diversity in the head regions of shared clonotypes. Further, head region diversity in shared clonotypes was inversely related to CDRH3 length, a relationship not seen in unshared clonotypes or synthetic repertoires (Figure 3E). This inverse relationship, along with the skewed distribution of CDRH3 lengths in shared clonotypes (Figure 3D), indicates two distinct processes shaping the shared clonotype population. The shortest shared CDRH3s encode head region diversity similar to unshared CDRH3s and synthetic CDRH3s of the same length (Figure 3F). Thus, short CDRH3s are likely shared primarily due to their lower CDRH3 diversity and concomitantly higher likelihood of independent generation by coincident recombination. In contrast, longer shared CDRH3s are less diverse than unshared or shared synthetic populations (Figure 3G) and more commonly encode head regions enriched in polar, uncharged residues and lacking hydrophobic residues (Figure 3H). This implies the existence of a mechanism by which these shared clonotypes are selected or enriched post-recombination based on the biochemical properties of their CDRH3 regions.

In summary, sequencing the circulating B cell population of ten individuals at unprecedented depth has revealed repertoires that are highly individualized and extremely diverse. We estimate cohort-wide repertoire diversity of approximately 5×109 unique heavy chain clonotypes and as many as 1×1011 unique heavy chain sequences. This indicates that the paired antibody diversity available to the circulating repertoire is very large, perhaps in the region of 1016-1018 unique antibody sequences. Despite enormous diversity, clonotypes are shared more frequently than would be expected from coincident V(D)J recombination. Further, we found that clonotype sharing likely is driven primarily by selection processes related to early B cell development rather than convergent responses to common antigens. The possible clinical and diagnostic applications of adaptive immune repertoire sequencing are myriad, however, much work remains. The results described here are confined to circulating B cells, which represent a minority of the total B cell population. The repertories of circulating and tissue-resident B cells are known to differ,19 and these differences may influence overall repertoire diversity and sharing. Further, we have only studied ten individuals from a limited age range (18–30 years) and geographic region at a single time point. Much larger cohorts representing diverse ethnicities, geographies and ages will be required to capture the true population-wide repertoire diversity. Nevertheless, large-scale sequencing of the human adaptive immune repertoire holds immense potential. Our use of high-level antibody feature frequencies to differentiate repertoires raises the possibility of identifying and classifying discrete repertoire perturbations associated with autoimmune disease and chronic infection. Further, because the adaptive immune receptor repertoire encodes a comprehensive record of an individual’s immunological encounters, leveraging large-scale adaptive immune receptor sequencing as a means to diagnose infection or deconvolute infection histories is appealing. Finally, the individuality of each subject’s baseline repertoire suggests that personalization of vaccine delivery and therapeutic intervention may produce substantial benefits in the treatment and prevention of infectious diseases.

METHODS

Leukapheresis samples

Full leukopaks (3 blood volumes) were obtained from ten human subjects (Hemacare). Samples were collected at Hemacare’s Southern California donor center. Sample collection was performed under a protocol approved by the Institutional Research Boards of Scripps Research and Hemacare. Informed consent was obtained from each subject. All subjects were healthy, HIV-negative adults between the ages of 18–30 with no reported acute illness in the 14 days prior to leukapheresis. The subject pool was gender balanced and evenly divided between African-American and Caucasian individuals (ethnicity was self-reported; Extended Data Table 1). Immediately upon receipt of the leukopak, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were purified by gradient centrifugation and cryopreserved.

Amplification strategy and primer bias

We elected to use RNA as the template for antibody variable gene amplification, as this focuses our analysis on productive heavy chain rearrangements and permits the use of amplification primers that anneal to the CH1 region (due to the presence of an intron between the JH gene and CH region, the use of CH1 primers is not feasible when amplifying from DNA). The decision to use RNA has some inherent downsides, however, primarily the likelihood of over-representation of transcriptionally active B cells (namely, memory B cells and plasmablasts). It should be noted that the use of molecular barcodes, which allow identification and collapsing of reads that originate from the same RNA molecule, will not correct this problem. To reduce the influence of multiplexed primer sets on the resulting composition of antibody genes that are amplified, we designed an amplification strategy that limits the use of multiplexed primers that anneal to the variable (V) gene region in an attempt to reduce primer bias during amplification. Following cDNA synthesis, 2nd strand synthesis was performed using multiplexed V gene primers that encode an overhang that comprises a portion of the Illumina adapters required for next-generation sequencing. V gene primers were then enzymatically removed before subsequent amplification of the antibody genes using the conserved overhang as the primer annealing site. Thus, the multiplexed V gene primers were only used for a single round of amplification.

Antibody gene amplification

For each subject, total RNA was separately isolated from 6 aliquots of approximately 5×108 cryopreserved PBMCs (RNeasy Maxi, Qiagen). For each RNA aliquot, antibody genes were amplified in triplicate (18 total samples per subject), with each of the technical replicates processed independently and starting with a separate aliquot of the RNA sample. To minimize the likelihood of cross-contamination between subjects, RT and PCR reactions for each subject were processed in isolation, such that samples from two different subjects were never in proximity during amplification reaction preparation. All primers20 are listed in Extended Data Table 2. In order to increase the sequencer-perceived nucleotide diversity during each sequencing cycle, “offsets” were added to the RT and 2nd strand synthesis primers. Three sets of these primers were synthesized, with each set containing either 2, 4 or 6 random nucleotides at the offset position (see Extended Data Table 2). These offsets stagger the conserved constant and framework regions and result in much higher diversity during each sequencing cycle and minimize the required PhiX spike. cDNA synthesis was performed on 11ul of RNA using 10pmol of each primer in a 20ul total reaction (SuperScript III, Thermo Fisher Scientific) using the manufacturer’s protocol and the following thermal cycling program: 55C for 60 minutes, 70C for 15 minutes. Residual primers and dNTPs were degraded enzymatically (ExoSAP-IT, Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The entire enzyme-treated cDNA synthesis product was used in a 100ul second strand synthesis reaction using 10pmol of each primer (HotStarTaq Plus, Qiagen) using the following thermal cycling protocol: 95C for 5 minutes, 55C for 30 seconds, 72C for 10 minutes. Residual primers and dNTPs were again degraded enzymatically (ExoSAP-IT) and dsDNA was purified using 0.8 volumes of SPRI beads (AmpureXP, Beckman Coulter Genomics) and eluted in 50uL of water. Antibody genes were amplified using 40uL of eluted dsDNA and 10pmol of each primer in a 100ul total reaction volume (HotStarTaq Plus) using the following thermal cycling program: 95C for 5 minutes; 25 cycles of: 95C for 30 seconds, 58C for 30 seconds, 72C for 2 minutes; 72C for 10 minutes. DNA was purified from the PCR reaction product using 0.8 volumes of SPRI beads (AmpureXP) and eluted in 50uL of water. 10ul of the eluted PCR product was used in a final indexing PCR (HotStarTaq Plus) using 10pmol of each primer in 100ul total reaction volume and using the following thermal cycling program: 95C for 5 minutes; 10 cycles of: 95C for 30 seconds, 58C for 30 seconds, 72C for 2 minutes; 72C for 10 minutes. PCR products were purified with 0.7 volumes of SPRI beads (SPRIselect, Beckman Coulter Genomics) and the entire set of samples from a single subject were eluted in a single 120ul volume of water.

Sequencing

SPRI-purified sequencing libraries were initially quantified using fluorometry (Qubit, Thermo Fisher Scientific) before size determination using a bioanalyzer (Agilent 2100). Libraries were re-quantified using qPCR (KAPA Biosystems) before sequencing on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 using 2×250bp Rapid Run chemistry.

Raw sequence processing

Raw paired FASTQ files were quality checked with FASTQC (www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/). Because the 5’ end of each paired read encodes the unique molecular identifier (UMI), reads were quality trimmed only at the 3’ end using Sickle (www.github.com/najoshi/sickle), using a window size of 0.1 times the length of the read, minimum average window quality score of 20, and a minimum read length after trimming of 50 nucleotides. Because UMIs are located on the ‘outside’ of the gene-specific primers used for amplification (see Extended Data Figure 1B), primer trimming was delayed until after UMI processing. Processed reads were quality checked again using FASTQC, and paired reads were merged with PANDAseq using the default (simple_bayesian) merging algorithm.21

Molecular barcodes

Although sequencing libraries were constructed to encode molecular barcodes on both ends of the amplicon, we observed low-level PCR recombination22 which produced “barcode swapping”, causing the frequency of these amplification artifacts to be amplified. In essence, a partial amplification product, composed of a CDRH3 and an incomplete VH gene, was able to prime a different antibody sequence and continue amplification, producing a hybrid VH gene. This hybrid amplicon encodes the 3’ molecular barcode from the primary antibody recombination and the 5’ molecular barcode from the second. The barcode swapping creates a unique barcode pair, forcing the hybrid sequence to be binned and processed separately. To minimize the effects of such barcode swapping, we binned sequences using only the 3’ molecular barcode. Because the likelihood of UMI collisions was relatively high given the sequencing depth, the CDRH3 nucleotide sequences of each UMI bin containing more than one sequence were clustered at high identity (90%) and a consensus sequence was computed for each cluster. For UMI bins containing only a single sequence, the lone sequence was used as the representative for the respective UMI bin. Because our sequencing depth was approximately equal to the number of input cells (~3×108 sequencing reads from ~3×108 input B cells), the majority of UMI bins contained only a single sequencing read. As such, the UMIs were not used primarily for error correction, but as a means for correcting differential representation arising from stochastic or primer-driven amplification biases. Mutation frequencies in the IgM and IgG sequence populations (Extended Data Figure 3) provide empirical evidence of a low amplification/sequencing error rate that corroborates sequencer-derived quality metrics.

Germline gene assignment and annotation

Adapters and V-gene amplification primers (used for second strand synthesis) were removed using cutadapt.23 cDNA synthesis primers, which anneal to the CH1 region, were not removed because this region is needed to determine the isotype. Sequences were annotated with abstar4 and two output formats were generated: a comprehensive JSON-formatted output, which was imported into a MongoDB database; and a minimal CSV-formatted output, which is tabular and suitable for direct parsing or conversion to Parquet for querying on a Spark cluster.

Antibody clonotypes

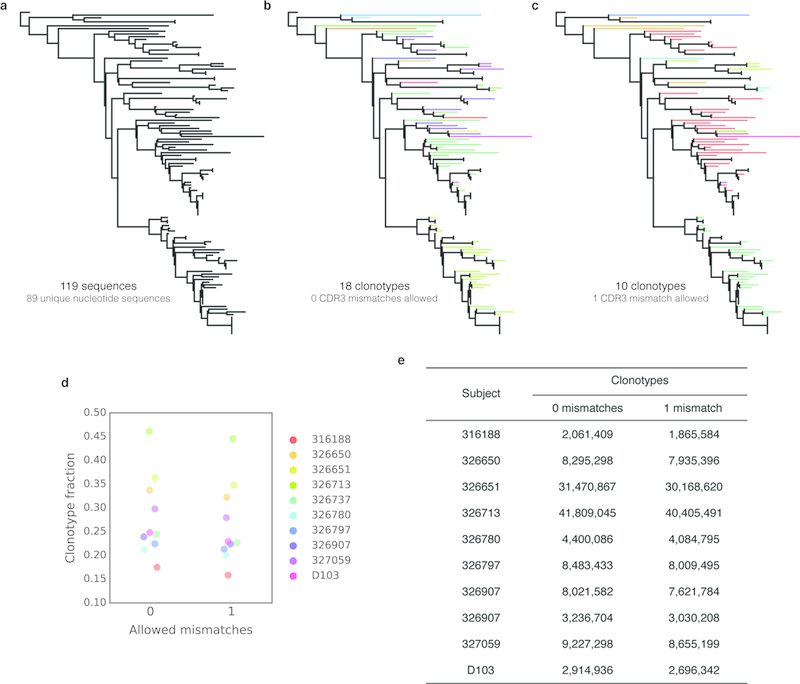

Antibody clonotypes, defined as a collection of sequences that use the same V and J germline segments and encode an identical CDRH3 amino acid sequence, were used throughout this study to reduce the influence of sequencing or amplification error. Although collapsing the V/J regions to just the germline assignment removes the possibility of double-counting sequences that differ only by error(s) in the V- or J-gene region, it does not eliminate the impact of error in the CDRH3. To gauge the effect of sequencing and amplification error in the CDRH3 on clonotype diversity, we collapsed sequences into clonotypes allowing either no mismatches in the CDRH3 amino acid sequence or allowing a single mismatch in the CDRH3. The total number of 1-mismatch clonotypes was lower than the number of 0-mismatch clonotypes by only 5.9% on average (3.4–9.5%), which is as expected when collapsing a sequence population containing expanded antibody lineages (Extended Data Figure 5) and indicates that CDRH3 sequencing errors do not contribute meaningfully to clonotype diversity. Thus, only 0-mismatch clonotypes were used for all further experiments utilizing clonotypes.

Estimation of light chain diversity relative to heavy chain diversity

Estimation of light chain diversity is, in some ways, more complex than estimating heavy chain diversity due to the relatively high frequency of coincidentally identical recombinations.24 Rather than sequencing unpaired light chains and attempting to discern independent rearrangements from distinct copies of RNA derived from the same recombination event, we leveraged a novel dataset of paired antibody heavy and light chains to estimate the diversity of light chains relative to the diversity of heavy chains.24 For each of the three subjects for which paired heavy/light sequencing data was available, we estimated the total richness using Chao2 and Recon estimators. Each subject was sequenced in duplicate, and separated estimates were computed for each sequencing replicate. Because the sequencing depth was far lower in the paired data set than in the large-scale experiment described here, we extrapolated the richness estimates so that the paired richness estimates were more comparable with the large-scale estimates. Although such an extrapolation may introduce a non-trivial amount of variance into the richness estimates, we believe that this provides the most accurate estimate of relative light chain diversity that is currently available. Diversity estimates and the associated extrapolations can be found in Extended Data Figure 7. The highest ratio of heavy chain to light chain richness (indicating the lowest diversity of light chains relative to heavy chains) was observed with the Chao2 estimator (3.8×103). Conservatively, we rounded this ratio up to the nearest order of magnitude (104) when computing the total paired repertoire diversity estimates.

Generating synthetic repertoires based on a probabilistic model of V(D)J recombination

We created a total of 3 billion synthetic antibody sequences using IGoR16 with one of three different approaches. First, we created 10 sequence batches, each containing 108 synthetic antibody sequences, using IGoR’s default recombination model, which was inferred from unproductive antibody rearrangements. The reason for using unproductive rearrangements for inferring IGoR’s default recombination model is that productive rearrangements are subject to a variety of selection processes during B cell maturation (negative selection of autoreactive clones, requirement for productive pairing with a light chain, etc), whereas unproductive rearrangements are subjected to none of these selection processes. Thus, a model inferred from unproductive rearrangements incorporates only information about the V(D)J recombination process. Second, we inferred subject-specific recombination models using 5×105 randomly selected IgM sequences that were entirely unmutated in the V-gene region. Ten synthetic sequence batches, each containing 108 sequences, were then generated, one batch per subject. Finally, we inferred a combined-subject recombination model using a pool of 5×105 umutated IgM sequences from all 10 subjects (5×104 sequences per subject, randomly selected from the sequences used to generate the subject-specific models). As with IGoR’s default model, 10 separate batches of 108 synthetic sequences were generated with the combined-subject model. All synthetic sequences were processed in the same manner as the observed antibody sequences, except that the adapter trimming and UMI-based correction steps were not performed. Kullback-Leibler divergence between models or model “events” was computed with the pygor package, which is distributed with IGoR (Extended Data Figure 8).

Morisita-Horn similarity

Antibody sequences from each subject were reduced to just the V-gene, J-gene and CDRH3 length (VJ-CDR3len) and were randomly sub-sampled with replacement at sample sizes ranging from 101-107. The frequency of each VJ-CDR3len was computed, and the frequency distributions from two donors was used to compute the Morisita-Horn similarity index:

where xi is the number of times VJ-CDR3len i is represented in one sample of size X and yi is the number of times VJ-CDR3len i is represented in a second sample of size Y.

Rarefaction

For each subject, all unique clonotypes from each of the biological replicates were pooled. For varying sample sizes (ranging from 0.1 to 1.0, as a fraction of the total number of pooled clonotypes), samples were randomly drawn without replacement and the number of unique clonotypes in the sample was computed. For each sample size, a total of 10 independent samplings were performed, with the exception of the 1.0 fraction, which was only sampled once (as samplings of the entire dataset will always produce the same result).

Classification of repertoires by subject

Repertoires were classified using one-vs-rest support vector machine classifier. Classifier training and evaluation were performed in Python using the scikit-learn framework. All code used for classification can be found at www.github.com/briney/grp_paper. It is important to note that this classification was performed using only 10 subjects and expanding the subject pool to thousands or millions of individuals while maintaining classifier accuracy would likely require much larger training datasets and/or the inclusion of additional sequence features to supplement the V-gene, J-gene, and CDRH3 length. Additionally, because the repertoire of each subject will be altered by new immunological encounters and ongoing turnover in the naive B cell population, it is possible that these high-level sequence feature frequencies will change substantially over time.

Statistical calculations

Statistical calculations were performed in Python using SciPy (www.scipy.org) or Seaborn (www.seaborn.pydata.org).

Extended Data

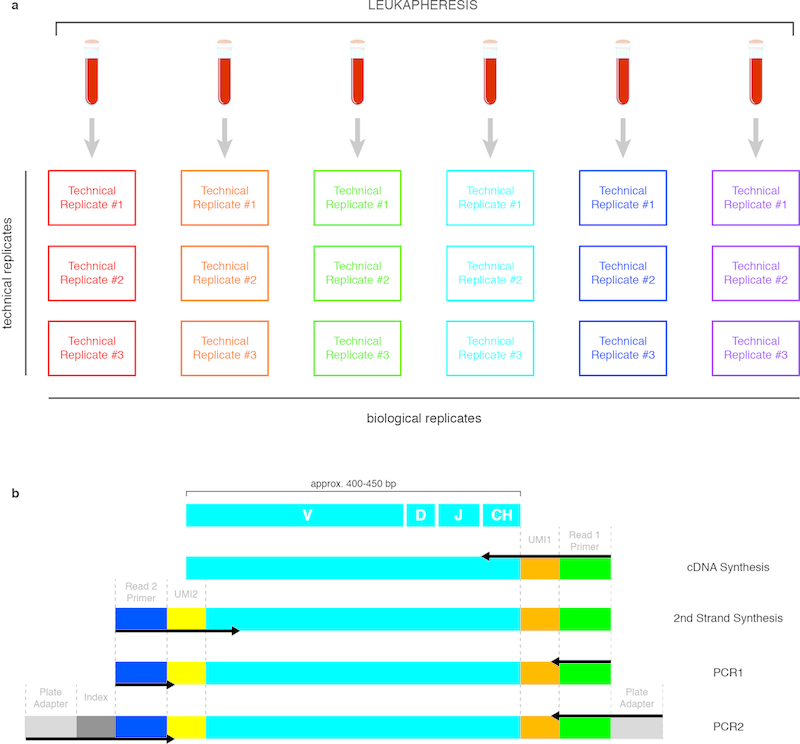

Extended Data Figure 1. Nearly full-length antibody gene amplification from biological and technical replicate samples.

a) Schematic of biological and technical replicate samples. Biological replicates (columns) are derived from distinct cell aliquots, so identical clonotypes or sequences found in multiple biological replicates must arise from different cells. Technical replicates (rows) were amplified using discrete RNA aliquots from a single cell aliquot. b) Strategy for nearly full-length antibody heavy chains. Black arrows indicate primers. Primers in the cDNA synthesis step anneal to the heavy chain constant region (CH) and add the first unique molecular identifier (UMI) and the Illumina read 1 primer annealing site. Primers in the 2nd strand synthesis step anneal to the framework 1 (FR1) region of the variable gene and add a second UMI and the Illumina read 2 primer annealing site.

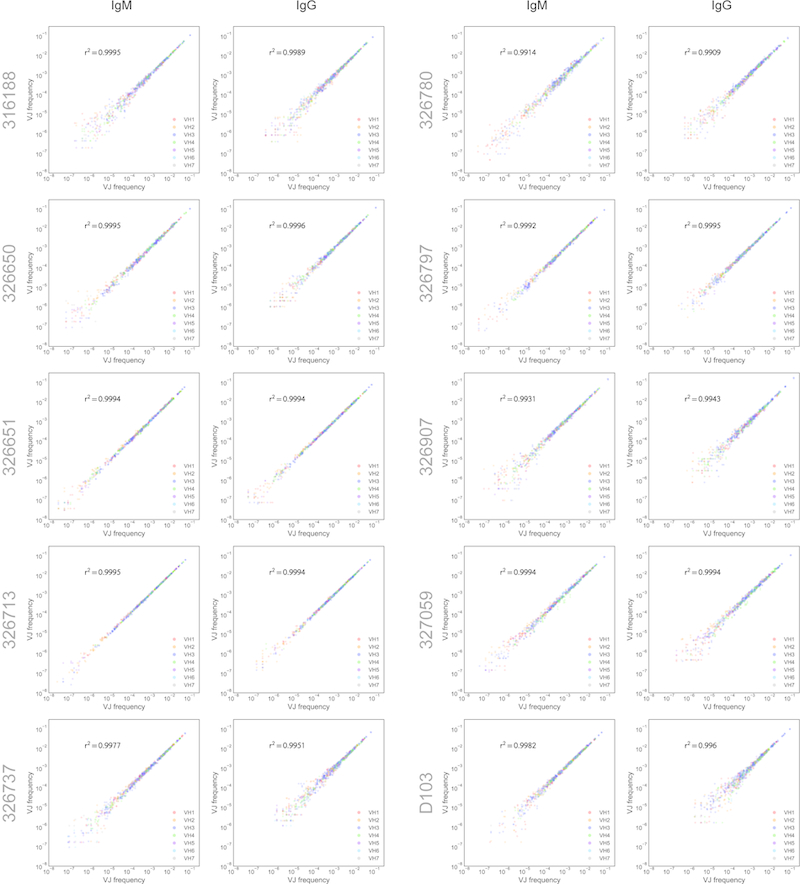

Extended Data Figure 2. V/J frequency correlations of technical and biological replicates.

For each subject, the frequency of V/J combinations was compared for technical replicates (left panels) or biological replicates (right panels). The coefficient of determination (r2) is shown for each plot.

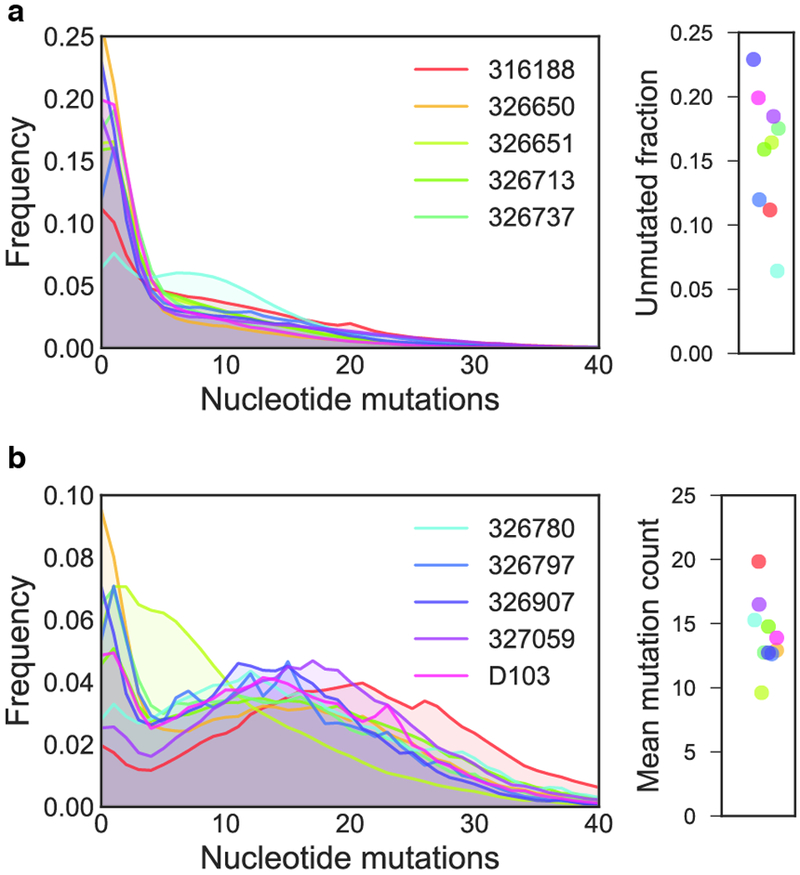

Extended Data Figure 3. Nucleotide mutation frequencies.

a) The distribution of nucleotide mutations in sequences encoding IgM are shown. On the right, the number of unmutated sequences containing no mutations in the variable gene segment is also plotted. b) The distribution of nucleotide mutations in sequences encoding IgG are shown. On the right, the mean mutation frequency for the IgG population of each subject is shown. Each line represents a single subject. For legibility, the legend is split between the two plots. Although only five subjects are shown in the legend of each plot, data from all ten subjects is present in each plot.

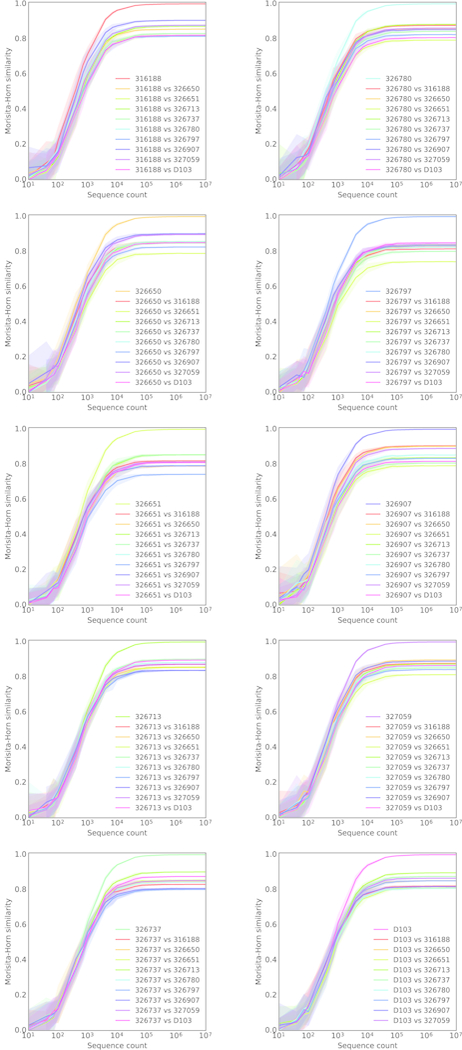

Extended Data Figure 4. Cross-subject repertoire similarity.

Pairwise Morisita-Horn similarity comparisons between each subject and all other subjects. Similarity was computed using the frequency of V-gene, J-gene and CDRH3 length combinations. Each line represents the mean of 20 independent repertoire samplings (with replacement). The shading surrounding the mean line indicates the 95% confidence interval.

Extended Data Figure 5. Collapsing sequences into clonotypes.

a) To demonstrate the effect of collapsing an expanded clonal lineage into clonotypes, we selected a previously reported lineage of Zika-specific monoclonal antibodies isolated from the plasmablast population of an acutely infected patient.25 Of 119 sequences, 89 were unique at the nucleotide level. b) Sequences encoding the same V-gene, J-gene and an identical CDRH3 amino acid sequence were collapsed into clonotypes, and the sequence phylogeny was colored by clonotype. 119 total sequences were collapsed into 18 clonotypes. c) Sequences were collapsed into clonotypes, allowing a single mismatch in the CDRH3 amino acid sequence, and the sequence phylogeny was colored by clonotype. 119 total sequences were collapsed into 10 clonotypes. d) The clonotype fraction (number of clonotypes divided by the total number of filtered sequences) when collapsing clonotypes while allowing zero or one mismatch in the CDRH3 amino acid sequence for each subject in this study. e) Number of total clonotypes recovered when allowing zero or one mismatch in the CDRH3 amino acid sequence for each subject in this study.

Extended Data Figure 6. Capture-recapture frequency.

a) Recapture frequency for each subject. Lines represent the mean of 10 random samplings (without replacement) for all subsample fractions except compete sampling (1.0). b) Mean recapture frequency for each subsample fraction.

Extended Data Figure 7. Relative light chain diversity estimation.

Using previously reported datasets of paired heavy and light antibody chains, clonotype diversity was estimated for heavy and light chains using both Chao2 and Recon estimators. Estimates are shown in filled or unfilled points. Lines indicate the least squares polynomial best fit (degree=2) and is extrapolated to include both the lowest (1.17×108) and highest (9.06×108) number of UMI-corrected sequences from the 10 sequenced subjects.

Extended Data Figure 8. Variance between inferred V(D)J recombination models.

a) Frequency of clonotype sharing between observed human subjects (black), synthetic datasets generated with IGoR’s default recombination model (red), synthetic datasets generated with subject-specific recombination models (blue) or synthetic datasets generated with a combined subjects recombination model (purple). b) Combined Kullback-Leibler divergence (KL divergence) between pairs of subject-specific models (blue), between subject-specific models and IGoR’s default model (red), or between subject-specific models and the combined-subject model (purple). c) Combined KL divergence between pairs of subject-specific models, separated by “event” type.

Extended Data Table 1. Per-subject demographic information and sequencing statistics.

All ethnicities are self-reported.

| Subject | Age | Gender | Blood Type | Ethnicity | Raw reads | Consensus sequences | Consensus |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 mismatch | 1 mismatch | |||||||

| 316188 | 30 | female | A-POS | AA | 320,844,194 | 11,767,640 | 2,061,409 | 1,865,584 |

| 326650 | 18 | female | O-POS | C | 218,356,368 | 24,592,893 | 8,295,298 | 7,935,396 |

| 326651 | 19 | male | O-POS | AA | 298,965,776 | 86,637,579 | 31,470,867 | 30,168,620 |

| 326713 | 25 | female | O-POS | AA | 228,526,194 | 90,598,768 | 41,809,045 | 40,405,491 |

| 326780 | 29 | male | O-NEG | C | 295,183,125 | 17,991,497 | 4,400,086 | 4,084,795 |

| 326797 | 21 | female | A-POS | C | 341,880,369 | 39,963,919 | 8,483,433 | 8,009,495 |

| 326907 | 29 | male | AB-POS | C | 275,955,787 | 35,726,036 | 8,021,582 | 7,621,784 |

| 326907 | 29 | female | O-NEG | AA | 267,970,240 | 13,528,917 | 3,236,704 | 3,030,208 |

| 327059 | 26 | male | B-POS | AA/C | 332,209,280 | 30,967,338 | 9,227,298 | 8,655,199 |

| D103 | 25 | male | O-NEG | C | 322,781,254 | 11,746,606 | 2,914,936 | 2,696,342 |

AA: African-American, C: Caucasian

Extended Data Table 2. Primers used for antibody gene amplification.

Regions in parenthesis indicate “offset” positions. Random offset nucleotides are added in multiples of 2. Xs indicate the position of Illumina TruSeq indexes.

| Name | Sequence | Step |

|---|---|---|

| lgM-RT | ACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCTNNNNNNNNNNNN(NNNNNN)GGTTGGGGCGGATGCACTCC | RT |

| lgG-RT | ACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCTNNNNNNNNNNNN(NNNNNN)SGATGGGCCCTTGGTGGARGC | RT |

| VH1-2SS | AGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCT(NNNNNN)GGCCTCAGTGAAGGTCTCCTGCAAG | 2nd strand synthesis |

| VH2-2SS | AGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCT(NNNNNN)GTCTGGTCCTACGCTGGTGAACCC | 2nd strand synthesis |

| VH3-2SS | AGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCT(NNNNNN)CTGGGGGGTCCCTGAGACTCTCCTG | 2nd strand synthesis |

| VH4-2SS | AGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCT(NNNNNN)CTTCGGAGACCCTGTCCCTCACCTG | 2nd strand synthesis |

| VH5-2SS | AGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCT(NNNNNN)CGGGGAGTCTCTGAAGATCTCCTGT | 2nd strand synthesis |

| VH6-2SS | AGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCT(NNNNNN)TCGCAGACCCTCTCACTCACCTGTG | 2nd strand synthesis |

| R1-fwd | GTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATC | PCR1 |

| R1-rev | ACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACG | PCR1 |

| R2-fwd | CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGAGATCGGTCTCGGCATTCCTGCTGAAGATXXXXXXGTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATC | PCR2 |

| R2-rev | AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATCTACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACG | PCR2 |

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank all of the study subjects for their participation and the Genomic Services Lab at the HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology for their sequencing expertise. This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (Center for HIV/AIDS Vaccine Immunology and Immunogen Discovery, UM1AI100663 [DRB]; Center for Viral Systems Biology, U19AI135995 [BB]), the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI) through the Neutralizing Antibody Consortium SFP1849 (DRB), and the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT, and Harvard (DRB).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Code availability statement

Code and data used to produce the figures are available at www.github.com/briney/grp_paper. Abstar is available at www.github.com/briney/abstar. Code for molecular barcode processing is available at www.github.com/briney/abtools.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Sequence data that support the findings in this study are available at the NCBI Sequencing Read Archive (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra) under BioProject number PRJNA406949. Raw and processed datasets, as well as code for data processing and figure generation, are available at www.github.com/briney/grp_paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rajewsky K Clonal selection and learning in the antibody system. Nature 381, 751–758 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alberts B et al. The Generation of Antibody Diversity. (Garland Science, 2002). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyd SD & Crowe JE Jr. Deep sequencing and human antibody repertoire analysis. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 40, 103–109 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Briney B & Burton D Massively scalable genetic analysis of antibody repertoires. bioRxiv 447813 (2018). doi: 10.1101/447813 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Briney B, Le K, Zhu J & Burton DR Clonify: unseeded antibody lineage assignment from next-generation sequencing data. Sci. Rep. 6, 23901 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morbach H, Eichhorn EM, Liese JG & Girschick HJ Reference values for B cell subpopulations from infancy to adulthood. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 162, 271–279 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morisita M Measuring of the dispersion of individuals and analysis of the distributional patterns. Mem. Fac. Sci. Kyushu Univ. Ser. E 2, 5–235 (1959). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horn HS Measurement of ‘Overlap’ in Comparative Ecological Studies. Am. Nat. 100, 419–424 (1966). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Setliff I et al. Multi-Donor Longitudinal Antibody Repertoire Sequencing Reveals the Existence of Public Antibody Clonotypes in HIV-1 Infection. Cell Host Microbe 23, 845–854.e6 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chao A Estimating the population size for capture-recapture data with unequal catchability. Biometrics 43, 783–791 (1987). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaplinsky J & Arnaout R Robust estimates of overall immune-repertoire diversity from high-throughput measurements on samples. Nat. Commun. 7, 11881 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chao A & Chiu C-H Nonparametric Estimation and Comparison of Species Richness in eLS (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eren MI, Chao A, Hwang W-H & Colwell RK Estimating the richness of a population when the maximum number of classes is fixed: a nonparametric solution to an archaeological problem. PLoS One 7, e34179 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeKosky BJ et al. In-depth determination and analysis of the human paired heavy- and light-chain antibody repertoire. Nat. Med. 21, 86–91 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arnaout R et al. High-resolution description of antibody heavy-chain repertoires in humans. PLoS One 6, e22365 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marcou Q, Mora T & Walczak AM High-throughput immune repertoire analysis with IGoR. Nat. Commun. 9, 561 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morea V, Tramontano A, Rustici M, Chothia C & Lesk AM Conformations of the third hypervariable region in the VH domain of immunoglobulins. J. Mol. Biol. 275, 269–294 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finn JA et al. Improving Loop Modeling of the Antibody Complementarity-Determining Region 3 Using Knowledge-Based Restraints. PLoS One 11, e0154811 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Briney BS, Willis JR, Finn JA, McKinney BA & Crowe JE Jr. Tissue-specific expressed antibody variable gene repertoires. PLoS One 9, e100839 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

EXTENDED DATA REFERENCES

- 20.van Dongen JJM et al. Design and standardization of PCR primers and protocols for detection of clonal immunoglobulin and T-cell receptor gene recombinations in suspect lymphoproliferations: report of the BIOMED-2 Concerted Action BMH4-CT98–3936. Leukemia 17, 2257–2317 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Masella AP, Bartram AK, Truszkowski JM, Brown DG & Neufeld JD PANDAseq: paired-end assembler for illumina sequences. BMC Bioinformatics 13, 31 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meyerhans A, Vartanian JP & Wain-Hobson S DNA recombination during PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 18, 1687–1691 (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin M Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet.journal 17, 10–12 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeKosky BJ et al. In-depth determination and analysis of the human paired heavy- and light-chain antibody repertoire. Nat. Med. 21, nm3743 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rogers TF et al. Zika virus activates de novo and cross-reactive memory B cell responses in dengue-experienced donors. Sci Immunol 2, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.