Abstract

Loneliness is associated with poor health outcomes, and there is growing attention on loneliness as a social determinant of health. Our study sought to determine the associations between community factors and loneliness. The Three-Item Loneliness Scale and zip codes of residence were collected in primary care practices in Colorado and Virginia. Living in zip codes with higher unemployment, poor access to health care, lower income, higher proportions of blacks, and poor transportation was associated with higher mean loneliness scores. Future studies that examine interventions addressing loneliness may be more effective if they consider social context and community characteristics.

Key words: loneliness, social determinants of health, social isolation

INTRODUCTION

The communities where patients live and work have an important role in health outcomes and perceived health.1 Recognizing the importance of social determinants of health, the National Academy of Medicine recommended that primary care clinicians routinely collect information on 12 social and behavioral domains.2 Social connections and social isolation were included as 1 of the domains, but loneliness, which is the subjective perception of the inadequacy of one’s social connections, was not.3 Although loneliness was initially emphasized in geriatric populations, there is growing recognition of its high prevalence in primary care settings, with an estimated prevalence of 20%.4 Furthermore, loneliness is associated with higher risk of premature death, dementia, high blood pressure, and depression as well as increased utilization of health services.3,5

Although these individual health associations with loneliness are well established, associations with community characteristics of place of residence are unknown. The National Academy of Medicine recommends including community characteristics in routine primary care,6 but it remains unclear whether doing so is of value compared with merely collecting patient information and unclear how clinicians could use this place-based information.7 Our study aimed to describe the associations between socioeconomic factors in communities and loneliness.

METHODS

Using a cross-sectional study design, we collected survey data from patients in 16 practices across 2 practice-based research networks: the Virginia Ambulatory Outcomes Research Network (ACORN) and the State Networks of Colorado Ambulatory Practices (SNOCAP). The survey used the Three-Item Loneliness Scale screening tool8 and also asked respondents for their zip code of residence, which we matched to Zip Code Tabulation Areas (ZCTAs.) The survey was collected on paper between April 2017 and January 2018 from patients aged 18 years and older while they were in the primary care waiting room before their appointment. Patients who could not read English were excluded. Patients were approached until 100 responses per practice were obtained or the end of a consecutive 7-day collection period, whichever occurred first. ZCTA-level community variables were obtained from American FactFinder9 and HealthLandscape.10 We included economic, demographic, transportation, and health care access variables. ZCTAs with <5 respondents were excluded.

Associations between ZCTA-level community variables and patient-level loneliness scores were estimated with a linear mixed model to account for clustering of patients within ZCTAs. Correlation coefficients were taken as the square root of the coefficient of determination, calculated via simple algebra from the resulting type III F-test statistic and numerator and denominator degrees of freedom (F = [R2/1 – R2] × [ndf/ddf]). The SAS statistical software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc) was used to perform analyses, and the R statistical software version 3.5.0 (the R Foundation) with the sp, rgdal, and classInt packages was used for mapping.

The study was approved by the Virginia Commonwealth University Institutional Review Board and the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

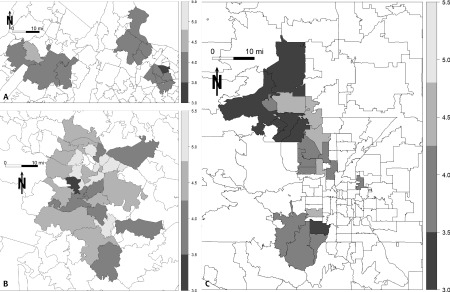

Of the 1,235 survey respondents (528 from SNOCAP and 707 from ACORN), 20% were identified as lonely (based on a score of 6 or higher on a scale of 1 to 9 on the Three-Item Loneliness Scale). A total of 44 ZCTAs from Virginia and 32 ZCTAs from Colorado were included in our analysis. A map showing the geographic distribution of loneliness is shown in Figure 1. In Richmond, Virginia, high loneliness score ZCTAs are adjacent. Scores in Denver, Colorado are lower overall.

Figure 1.

Mean loneliness score by zip code of residence in (A) Northern Virginia, (B) Metro Richmond, Virginia, and (C) Metro Denver, Colorado.

Patients living in ZCTAs with higher poverty, higher Social Deprivation Index scores, higher proportions of unemployment and of individuals with less than a high school education, and lower median household income were associated with higher mean loneliness scores. Those in ZCTAs with proportionally more 1-person households, females, and blacks had higher mean loneliness scores. Patients in ZCTAs with a higher mean travel time and with higher percentages of households with no vehicle had higher levels of loneliness. Patients in ZCTAs with higher percentages of residents without health insurance and without a usual source of care had higher loneliness scores. Associations are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Associations Between Loneliness and Geospatial Variables, by Zip Code Tabulation Area of Residence

| Pearson Correlation | P Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Economic variables | ||

| Poverty (<200% federal poverty line) | 0.35 | 0.02 |

| Social Deprivation Index scorea | 0.42 | <0.01 |

| Unemployed, % | 0.49 | <0.01 |

| Less than high school education, % | 0.45 | <0.01 |

| Median household income | –0.29 | 0.02 |

| Demographic variables | ||

| Median age | –0.07 | 0.52 |

| Female/male ratio | 0.27 | <0.01 |

| Race (% black) | 0.18 | <0.01 |

| Ethnicity (% Hispanic) | –0.13 | 0.27 |

| Linguistically isolated households, %b | 0.04 | 0.76 |

| Household size 1 person, % | 0.29 | 0.01 |

| Average household size | –0.07 | 0.53 |

| Transportation variables | ||

| Mean travel time to work | 0.15 | <0.01 |

| Households with no vehicle, % | 0.34 | <0.01 |

| Health care access variables | ||

| Without health insurance, % | 0.12 | <0.01 |

| Without usual source of health care, % | 0.37 | <0.01 |

The Social Deprivation Index is a composite measure of social and material deprivation encompassing education, housing, transportation, and poverty.

Households are considered linguistically isolated if all individuals ages 14 years and older in the household speak a language other than English and none speaks English well.

DISCUSSION

Living in a socioeconomically disadvantaged community is associated with higher mean loneliness scores. As others have shown, neighborhoods affect social relationships and interactions.1,2 These findings reinforce current calls by the National Academy of Medicine and other national leaders to routinely collect place of residence because of its influence on individual health and the need for interventions that address not only individual but also community-level factors that contribute to health and well-being.2 However, current screening tools are lengthy and may be difficult to routinely administer in primary care settings. Given the associations between loneliness and other community-level factors, screening for loneliness may be a proxy for other social needs. Primary care practices could play a leading role in developing and testing these interventions for loneliness, and loneliness could be an important first social need to address.

There are several limitations with our study. First, although we had 1,235 survey respondents across Virginia and Colorado, we were able to include only a minority of ZCTAs from each state (Virginia, 44/896; Colorado, 32/536). Second, because of the dispersion of the ZCTAs included, we were unable to perform more in-depth geospatial analyses. Even with this sample, however, we still found many significant associations.

This study reports the many associations between community-level variables and loneliness. Studies to replicate these findings with a more contiguous sample may help develop collaborative community–primary care interventions to address social determinants and loneliness, ultimately improving health outcomes for those with loneliness.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: authors report none.

References

- 1.Artiga S, Hinton E. Beyond health care: the role of social determinants in promoting health and health equity. https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/beyond-health-care-the-role-of-social-determinants-in-promoting-health-and-health-equity/. Published May 10, 2018 Accessed Jul 30, 2018.

- 2.Institute of Medicine. Capturing Social and Behavioral Domains and Measures in Electronic Health Records: Phase 2. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daaleman TP. The long loneliness of primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(5):388–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mullen R, Tong S, Sabo R, et al. Loneliness in primary care patients: a prevalence study. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(2):108–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holt-Lunstad J. The potential public health relevance of social isolation and loneliness: prevalence, epidemiology, and risk factors. Public Policy Aging Rep. 2017; 27(4): 127–130. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blumenthal D, McGinnis JM. Measuring vital signs: an IOM report on core metrics for health and health care progress. JAMA. 2015; 313(19): 1901–1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tong ST, Liaw WR, Kashiri PL, et al. Clinician experiences with screening for social needs in primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018; 31(3): 351–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: results from two population-based studies. Res Aging. 2004; 26(6): 655–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.United States Census Bureau. American fact finder. http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml Accessed Jul 9, 2018.

- 10.Robert Graham Center. HealthLandscape. http://www.healthlandscape.org Accessed Jul 9, 2018.