Abstract

Coordination complexes can be used to photocage biologically active ligands, providing control over the location, time, and dose of a delivered drug. Dual action agents can be created if both the ligand released and the ligand-deficient metal center effect biological processes. Ruthenium (II) complexes coordinated to pyridyl ligands generally are only capable of releasing one ligand in H2O, wasting equivalents of drug molecules, and producing a Ru(II) center that is not cytotoxic. In contrast, Ru(II) polypyridyl complexes containing diazine ligands eject both monodentate ligands, with the quantum yield (ϕps) of the second phase varying as a function of ligand pKa and the pH of the medium. This effect is general, as it is effective with different Ru(II) structures, and demonstrates that diazine-based drugs are the preferred choice for the development of light-activated dual action Ru(II) agents.

Graphical Abstract

Light-triggered Ru(II) molecules that produce active species capable of forming covalent adducts with DNA are being actively explored for photoactivated chemotherapy (PACT).1 A complementary and potentially compatible approach is “photocaging,” where a biologically active, monodentate ligand is masked by coordination to a metal center.2–7 Photo-release of this ligand allows for temporal and spatial control over activity. However, a persistent issue that has limited the utility of Ru(II) photocages is the sluggish photochemistry associated with ejecting the monodentate ligand. Strain-inducing bidentate ligands are known to activate dissociative photochemical pathways within cells,8–11 and have been used to increase the photo-lability of the monodentate ligand.12–14

“Dual action” light-activated Ru(II) compounds, where both the metal center and the liberated ligands induce different, potentially synergistic biological effects, are also of interest.15–16 The same issue hampers development of such dual action agents, however, as photocages; the photoreactivity of the second ligand is often orders of magnitude lower than the first.17 This sub-optimal photochemistry result in the waste of one equivalent of the drug ligand, but more importantly, the opening of two binding sites on the metal appears important for the creation of the Ru(II) cytotoxic species.18,19–20 This is in notable contrast to platinum species such as phenanthrinplatin, a highly potent cytotoxin with only one reactive site.21

The limitation of photoejection of only one ligand has been demonstrated for Ru(II) photocages containing pyridine, imidazole, aliphatic amine derivatives,22 and phosphine ligands.23 These light-induced ligand dissociation phenomena have been explored by ultrafast spectroscopy techniques and computational approaches.24–25 In contrast, release of two monodentate ligands has been shown for complex with 5-cyanouracil,26 demonstrating that Ru(II) bound nitriles undergo light-activated ligand exchange more efficiently than other monodentate ligands.7 However, the second ligand ejection is slow, and the majority of nitrile-containing drugs, including anticancer agents, are derivatives of nitrogen-containing heterocycles.27 Therefore, coordination with a Ru scaffold by a direct synthetic pathway could be complicated by the presence of coordination isomers in the prodrug molecule.

Considering the difference between acid-base properties and photochemical behaviors for Ru(II) complexes with aliphatic amines or pyridine (hard and borderline bases, respectively) and nitriles (soft bases),28,29 we hypothesized that cis-[Ru(bpy)2(L2)]2+ (bpy = 2,2’-bipyridyl) complexes with monodentate diazines (which are softer bases then pyridine) would efficiently release two ligands upon light irradiation in aqueous media. This hypothesis is partially supported by the fact that incorporation of the bidentate diazine ligand bipyrimidine in Ru(II) complexes results in a photochemically active species without any strain-inducing groups, in marked contrast to bipyridine complexes.29–30 Diazines are privileged heterocycles in medicinal chemistry,9 and are bioisosteres for pyridine and phenyl rings, so this study was further motivated by the presence of these moieties in several known drugs and the potential for incorporation in many more. The results of this report may be applied as a started platform to develop improved light-activated photocages and dual-action ruthenium complexes with diazine-based antitumor agents.

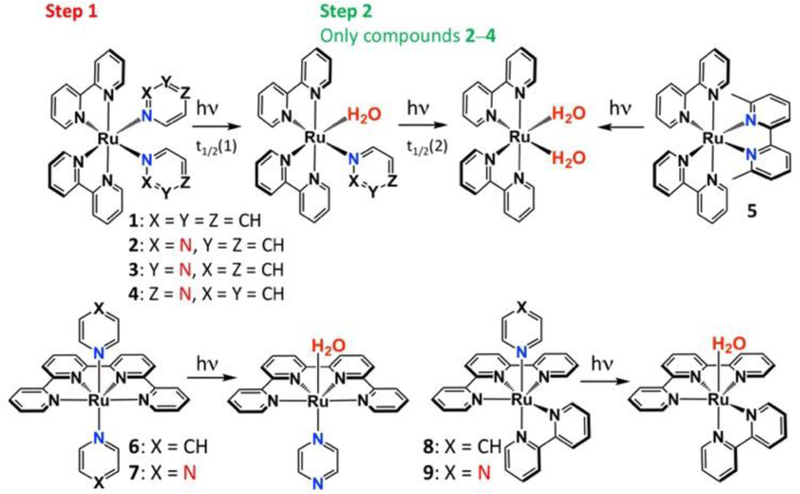

Three complexes with isomeric diazine coligands, cis-[Ru(bpy)2(pyd)2]2+ (pyd = pyridazine; compound 2), cis-[Ru(bpy)2(pym)2]2+ (pym = pyrimidine; 3), and cis-[Ru(bpy)2(pyz)2]2+ (pyz = pyrazine; 4) were synthesized and their photochemical properties compared to cis-[Ru(bpy)2(py)2]2+ (1; py = pyridine; Scheme 1). The complexes were prepared under low light conditions by refluxing cis-[Ru(bpy)2Cl2] with a 10-fold excess of the desired diazine in ethanol:water (1:1). Complexes 1, 2 and 4 have been reported previously,31–32 including the photophysical properties33 and some photosubstitution reactions34 for complexes 1 and 2. NMR spectroscopy and X-ray crystal structure have been reported for 1,32 though noteworthy differences were found in the NMR of compound 1.35

Scheme 1.

Photochemical reactions of complexes included in this study in H2O.

Structural analysis by x-ray crystallography revealed distorted octahedral geometries for complexes 2 and 3. The complexes exhibited altered [Ru−N] bond lengths in comparison to pyridine-containing 1 (Table S4);32 the Ru−N(pyd) and Ru−N(pym) bonds (2, 3) are equal, in contrast to Ru-N(py) bonds (1) where different length were found (2.063 and 2.13 Å). The N-Ru-N bond angles between diazine ligands are also distorted from ideal 90° and 180°, with the deviations of N2*-Ru-N2 (angle between trans-nitrogens in the bpy coligands) for complexes 2 (8.04°) and 3 (6.74°) larger than for 1 (5°) (Fig. S1A, C). The pyridazine ligands are bent from N2 (the top bpy nitrogen, Fig. S1B) with different bond angles (88.44° and 97.13°), and the bond angle between pyridazines is 92.53° in contrast to 90° between pyridine ligands in complex 1.32 This distortion was anticipated to affect the photochemical reactivity of the complexes.

All four Ru(II) complexes (1–4) were relatively stable in the dark for 72 h at 37 °C (Fig. S21), and exhibited selective photoejection of the first monodentate ligand in water (monitored by absorption spectroscopy; Scheme 1; Fig. S2–5) when irradiated with 470 nm light. The presence of an isosbestic point was interpreted as indicating the direct conversion to a single product. Compound 1 formed cis-[Ru(bpy)2(py)(H2O)]2+ (see absorption profile in Fig. 2B) and no further ligand loss was observed.

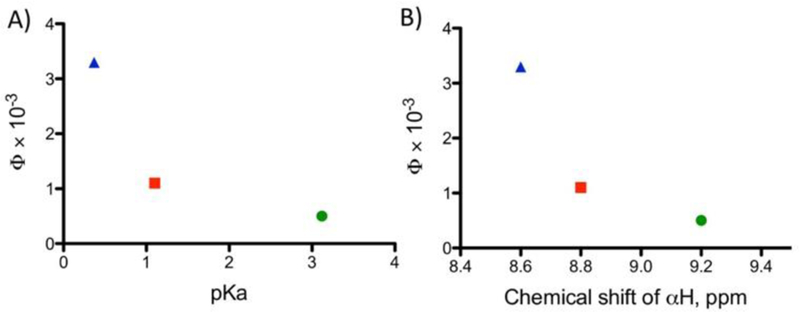

Fig. 2.

Correlation between quantum yields for the second ligand ejection for 2 (green ○), 3 (red □), 4 (blue Δ) and pKa of protonated free diazines (A) or chemical shifts of α protons of diazine ligands (B).

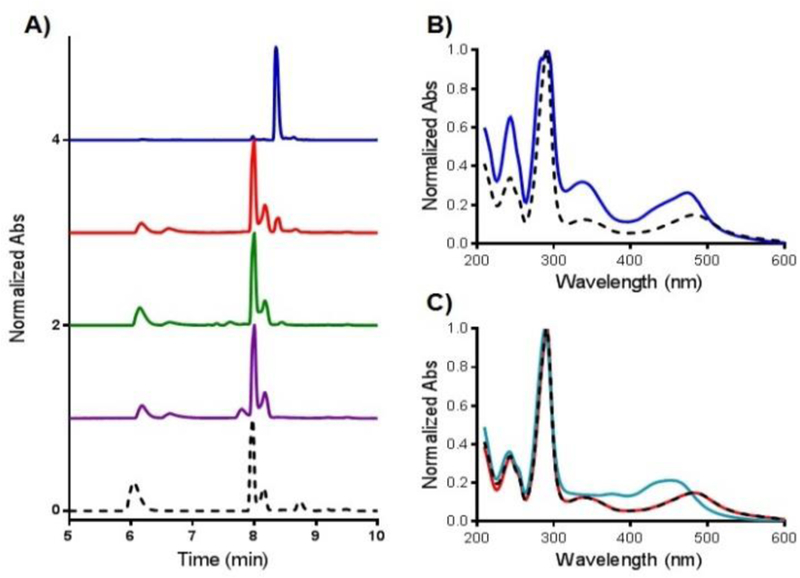

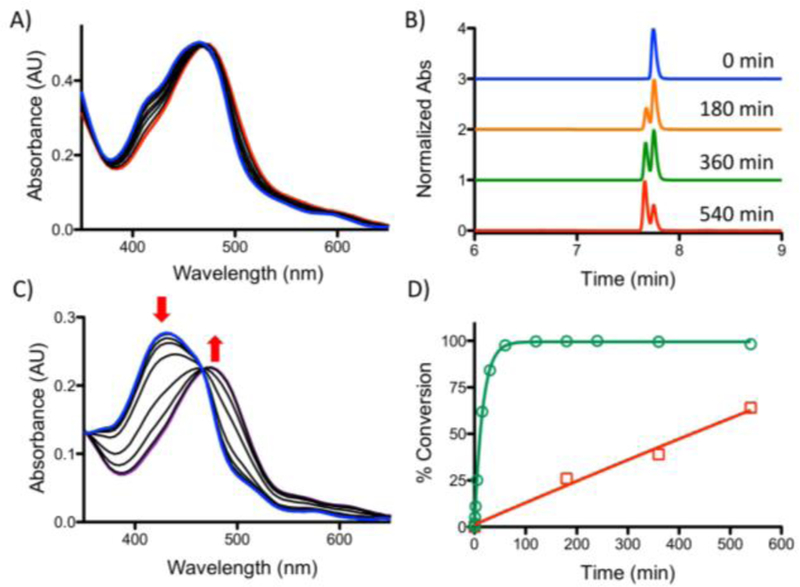

In marked contrast, a second photoreaction was observed for compounds 2–4 (Fig. 1A, C, S3–5). The quantum yields of photosubstitution by water (ϕPS) are shown in Table 1 and half-lives (t1/2) are provided in Table S13. Only the diazine complexes ejected two ligands. The first ligand photoejection is facile, with t1/2(1) of less than 1 min for complexes 1–4 and ϕPS of 0.031–0.11. In contrast, the ϕPS (2) for 2–4 in water were inverted relative to ϕPS (1), indicating both the sensitivity of the photochemistry to the identity of diazine ligand, and the presence of a specific chemical feature that drives the disparity in the yields of these sequential processes. The ϕPS values for the second ligand ejection ranged from 0.0005–0.0033, with 4 exhibiting the highest quantum yield. The product was identified as cis-[Ru(bpy)2(H2O)2]2+ by both HPLC and absorption spectroscopy (Fig. 1A, S3–5). The retention time (RT) and absorption profile was compared with [Ru(bpy)2]-based products after irradiation of strained compound 5 [Ru(bpy)2(dmbpy)]2+ (dmbpy – 6,6’-dimethyl-2,2’-bipyridyl).8 Further exposure of cis-[Ru(bpy)2(H2O)2]2+ to light after photoejection resulted in a decrease in the intensity of the MLCT (metal-to-ligand charge-transfer) absorption band at 490 nm following irradiation after 90 (4), 120 (3) and 150 (2) minutes, likely due to oxidation of the Ru(II) center.13

Fig. 1.

Determination of photoejection products by HPLC. A) Chromatogram of 1 (blue line, after 60 min irradiation), 2 (red line), 3 (green line) and 4 (violet line) after 120 min irradiation in comparison to 5 (black dash line, after 15 min irradiation). B) Absorption profile of Ru(II) photoproducts of 1 (blue line, RT = 8.35 min, cis-[Ru(bpy)2(py)(H2O)]2+) and 5 (black dash line, RT = 7.87 min, cis-[Ru(bpy)2(H2O)2]2+). C) Absorption profile of Ru(II) photoproducts of 2 after ejection of first (cyan line, 5 min irradiation, RT = 8.36 min) and second pyridazine ligand (red line, 120 min irradiation, RT = 7.99 min) overlaid with with cis-[Ru(bpy)2(H2O)2]2+ (black dash line, RT = 7.87 min).

Table 1.

Photophysical and photochemicala properties of compounds 1–9 in H2O

| Compound | λmax abs (nm)b | ϕPSd | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | (1) | (2) | |

| 1 | 455 | - | 0.031 | - |

| 2 | 420 | 450 | 0.11 | 0.0005 |

| 3 | 415 | 460 | 0.070 | 0.0011 |

| 0.059e | 0.0013e | |||

| 4 | 405 | 445 | 0.11 | 0.0033 |

| 5 | 0.022 | - | ||

| 6 | nd | nd | ||

| 7 | nd | nd | ||

| 8 | nd | - | ||

| 9 | 0.007 | - | ||

Measured using a 13 mW/cm2 470 nm LED.

For the MLCT.

From the fit to a single exponential.

See SI for a detailed description.

Determined by HPLC.

An inverse relationship was found between ϕPS(2) for complexes 2–4 and the pKa values for protonated parent ligands, as shown in Fig. 2A. The weaker basic dizaine ligands are more photolabile, and there was no ejection of the pyridine, which is the strongest base in this series. The quantum yields also correlate with chemical shifts of the α protons of the diazine ligands (Fig. 2B). In addition, ϕPS and t1/2(2) were found to be sensitive to the environment (pH), as compounds 2–4 demonstrated 1.7–2-fold faster ligand ejection in HCl-KCl buffer, pH = 2 than in sodium phosphate buffer, pH=7.4 (Table S4). A similar effect was observed with 1.8–3.5-fold faster t1/2 values in D2O vs. H2O. A possible explanation is that engagement of the non-bonding electrons of the uncoordinated aza nitrogen, either through protonation or hydrogen bonding, accelerates the photochemistry either by forming a pre-encounter complex with the incoming ligand or by polarizing the electrons on the diazine ligand.

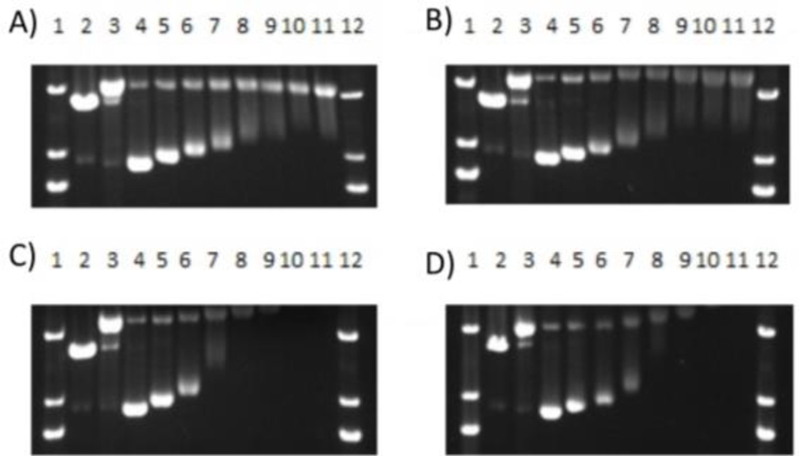

DNA damage was assessed by gel electrophoresis (Fig. 3). Incubation of each Ru(II) complex with plasmid DNA in the dark showed no interactions (Fig. S8), in contrast to the two types of DNA damage observed upon irradiation with 470 nm light. The diazine complexes 2–4 undergo ligands loss and covalent attachment to DNA, as observed by the reduction of DNA mobility and loss of ethidium bromide (EtBr) staining. Complex 1 created a combination of covalent damage and single strand breaks to form relaxed circular DNA, possibly through sensitization of singlet oxygen (1O2). There is some indication of single strand breaks for compound 2 as well, which has the slowest t1/2(2) of the diazine-containing complexes. Systems that both photoeject and create reactive oxygen species have previously been identified as useful dual mechanism agents;8, 36 if a diazine-containing drug were ligated, these would become triple action agents.

Fig. 3.

Agarose gel electrophoresis showing the dose response of compounds A) 1, B) 2, C) 3 and D) 4 incubated with 40 μg/mL pUC19 DNA with irradiation (470 nm light). Lanes 1 and 12, DNA ladder; lane 2, EcoRI; lane 3, Cu(OP)2; lane 4−11, 0−500 μM. EcoRI and Cu(OP)2 are controls for linear and relaxed circle DNA. See SI for full gels.

In order to determine if incorporation of diazines for improvement of Ru(II) complexes photo-lability is generalizable to other Ru(II) structures, the photochemistry of two trans-Ru(II) complexes containing pyridine (6) and pyrazine (7) ligands was investigated. Previously, trans Ru(II) complex containing thermally exchangeable ligands exhibited higher potency than an analogous cis compound,37 making this an appealing scaffold for the creation of dual action agents. Accordingly, trans-[Ru(qpy)(pyz)2]2+ (7; qpy = 2,2’:6’,2’’:6’’,2’’’-quaterpyridine) was synthesized and compared to the pyridine analogue 6, which is photo-stable in aqueous media. In contrast, the trans-Ru(II) complex with pyrazine ligands ejected the pyrazine ligand upon irradiation for nine hours (Fig. S9).

Finally, to demonstrate the useful application for a pure “photocaging” approach,38–39 two Ru(II) complexes (8, 9) were synthesized using a [Ru(tpy)(bpy)]2+ scaffold (tpy=2,2’;6’−2’’-terpyridine). The photochemical reaction of the complex containing pyridine, [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(py)]2+ (8), did not reach completion after nine hours irradiation (Fig. 4A, B), which is consistent with previous reports of ϕPS < 10−5 in MeCN.40,41 In contrast [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(pyz)]2+ (9) exhibited significantly enhanced photolability of pyrazine upon irradiation in aqueous media, with t1/2=10 min and complete ligand exchange in two hours (Fig. 4C, D, ϕPS = 0.007 in water). This significantly improved photochemistry makes [Ru(tpy)(bpy)]2+ a useful photocage in water if a diazine ligand is used.

Fig. 4.

Photochemistry of [Ru(tpy)(bpy)(L)]2+ complexes. A) Absorption spectra of 8 with irradiation (blue line, t=0, red line, t= 540 min). B) HPLC of 8 as a function of irradiation time. C) Absorption spectra of 9 with irradiation (blue line, t=0, red line, t= 100 min). D) Comparison of % conversion for 8 (red open □) and 9 (green open ○). The integrated area under the peaks from B) was used for % conversion of 8.

In conclusion, rather than incorporating strain-inducing bidentate ligands in Ru(II) scaffolds8–10, 42 or substituting monodentate ligands with electron withdrawing groups,43 these results demonstrate that simply using diazine ligands radically improves photochemical features. The approach works for a variety of Ru(II) scaffolds, and facilitates the ejection of two ligands from the cis-[Ru(bpy)2]2+ cage. We posit that simple electronic tuning by switching from pyridine to diazine systems is a far more efficient and flexible approach for the creation of functional light-activated metal complexes. These results suggest that photochemistry can be tuned by judicious use of ligands based on pKa values and HSAB theory.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the National Institutes of Health (Grant GM107586) for the support of this research. Crystallographic work was made possible by the National Science Foundation (NSF) MRI program, grants CHE-0319176 and CHE-1625732.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Notes and references

- 1.Farrer NJ; Salassa L; Sadler PJ, Dalton Trans 2009, (48), 10690–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zayat L; Calero C; Albores P; Baraldo L; Etchenique R, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2003, 125 (4), 882–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zayat L; Salierno M; Etchenique R, Inorg. Chem 2006, 45 (4), 1728–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Respondek T; Garner RN; Herroon MK; Podgorski I; Turro C; Kodanko JJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133 (43), 17164–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li A; Turro C; Kodanko JJ, Chem. Commun 2018, 54 (11), 1280–1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Renfrew AK, Metallomics 2014, 6 (8), 1324–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mosquera J; Sanchez MI; Mascarenas JL; Eugenio Vazquez M, Chem Commun (Camb) 2015, 51 (25), 5501–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howerton BS; Heidary DK; Glazer EC, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134 (20), 8324–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wachter E; Heidary DK; Howerton BS; Parkin S; Glazer EC, ChemComm 2012, 48 (77), 9649–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hidayatullah AN; Wachter E; Heidary DK; Parkin S; Glazer EC, Inorg. Chem 2014, 53 (19), 10030–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Havrylyuk D; Heidary DK; Nease L; Parkin S; Glazer EC, Eur. J. Inorg. Chem 2017, 2017 (12), 1687–1694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arora K; White JK; Sharma R; Mazumder S; Martin PD; Schlegel HB; Turro C; Kodanko JJ, Inorg Chem 2016, 55 (14), 6968–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huisman M; White JK; Lewalski VG; Podgorski I; Turro C; Kodanko JJ, Chem Commun (Camb) 2016, 52 (85), 12590–12593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wei J; Renfrew AK, J. Inorg. Biochem 2018, 179, 146–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zamora A; Denning CA; Heidary DK; Wachter E; Nease LA; Ruiz J; Glazer EC, Dalton Trans 2017, 46, ,2165–21l73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan H; Ghrayche JB; Wei J; Renfrew AK, Eur. J. Inorg. Chem 2017, 2017 (12), 1679–1686. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith NA; Zhang P; Greenough SE; Horbury MD; Clarkson GJ; McFeely D; Habtemariam A; Salassa L; Stavros VG; Dowson CG; Sadler PJ, Chem Sci 2017, 8 (1), 395–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The cytotoxicity appears to depend on the coligands used.

- 19.Cuello-Garibo JA; Meijer MS; Bonnet S, Chem Commun (Camb) 2017, 53 (50), 6768–6771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sgambellone MA; David A; Garner RN; Dunbar KR; Turro C, J Am Chem Soc 2013, 135 (30), 11274–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park GY; Wilson JJ; Song Y; Lippard SJ, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012, 109 (30), 11987–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.White JK; Schmehl RH; Turro C, Inorganica Chim Acta 2017, 454, 7–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Franco S; Manuel SR; Samira NG; Antonio R, Eur. J. Inorg. Chem 2016, 2016 (10), 1528–1540. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salassa L; Garino C; Salassa G; Gobetto R; Nervi C, J Am Chem Soc 2008, 130 (29), 9590–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenough SE; Roberts GM; Smith NA; Horbury MD; McKinlay RG; Zurek JM; Paterson MJ; Sadler PJ; Stavros VG, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2014, 16 (36), 19141–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garner RN; Gallucci JC; Dunbar KR; Turro C, Inorg. Chem 2011, 50 (19), 9213–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fleming FF; Yao L; Ravikumar PC; Funk L; Shook BC, J. Med. Chem 2010, 53 (22), 7902–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.House JE, Inorganic Chemistry, p. 297–98.

- 29.Crutchley RJ; Lever ABP, Inorg. Chem 1982, 21 (6), 2276–2282. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vicendo P; Mouysset S; Paillous N, Photochem. Photobiol 1997, 65 (4), 647–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adeyemi SA; Johnson EC; Miller FJ; Meyer TJ, Inorg. Chem 1973, 12 (10), 2371–2374. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hitchcock PB; Seddon KR; Turp JE; Yousif YZ; Zora JA; Constable EC; Wernberg O, J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans 1988, (7), 1837–1842. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Caspar JV; Meyer TJ, Inorg. Chem 1983, 22 (17), 2444–2453. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pinnick DV; Durham B, Inorg. Chem 1984, 23 (10), 1440–1445. [Google Scholar]

- 35.In contrast to the described 1H NMR spectrum (360 MHz, (CD3)2SO) for 1, some resonances for H5 and H5’ of bpy coligands (1–4) are present as doublet of doublets of doublets (ddd) (Figure S10). Detailed NMR spectra and interpretations are presented in Supporting Information.

- 36.Loftus LM; White JK; Albani BA; Kohler L; Kodanko JJ; Thummel RP; Dunbar KR; Turro C, Chemistry – A European Journal 2016, 22 (11), 3704–3708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wachter E; Zamora A; Heidary DK; Ruiz J; Glazer EC, Chem. Commun 2016, 52 (66), 10121–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lameijer LN; Ernst D; Hopkins SL; Meijer MS; Askes SHC; Le Devedec SE; Bonnet S, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 2017, 56 (38), 11549–11553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li A; Yadav R; White JK; Herroon MK; Callahan BP; Podgorski I; Turro C; Scott EE; Kodanko JJ, Chem Commun (Camb) 2017, 53 (26), 3673–3676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ru(II) complexes have higher quantum yields in MeCN than in water.

- 41.Knoll JD; Albani BA; Durr CB; Turro C, J. Phys. Chem. A 2014, 118 (45), 10603–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Knoll JD; Albani BA; Turro C, Acc Chem Res 2015, 48 (8), 2280–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vu AT; Santos DA; Hale JG; Garner RN, Inorg. Chim. Acta 2016, 450, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.