Abstract

Purpose:

To evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of a protocol determining the relationship between emergency team response (ETR) during childbirth and acute stress disorder (ASD) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms.

Methods:

In a prospective, observational, cohort design, women experiencing ETR during childbirth were approached and recruited on postpartum day 1 and followed for six weeks. Demographics, obstetric and birth characteristics, ASD scores and PTSD scores (by Impact of Events Scale, IES and PCL-civilian) were recorded. Recruitment and retention rates were recorded, and scores were compared to women who did not experience ETR.

Results:

369 were approached and 249 were enrolled (67.5% recruitment rate). 125 completed all procedures (50.2% retention). 20 experienced ETR (3.5% event rate), 12 enrolled (60.0% recruitment rate) and 8 completed the study (66.7% retention). The ETR group had higher PCL and IES scores (PCL: ETR median 12, non-ETR median 2, P = 0.08; IES: ETR median 22.5, non-ETR median 20, P = 0.08). ASD scores were similar between groups.

Conclusions:

Methodology investigating the link between ETR and postpartum psychological distress is feasible and acceptable. A relationship between ETR and PTSD symptoms appears to exist, with ETR being associated with higher PTSD scores compared to non-ETR childbirths. Methods that incorporate awareness of the unique concerns of vulnerable populations are needed.

Keywords: Postpartum, PTSD, ASD, trauma, morbidity, obstetric

Introduction

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a condition defined by disruptive symptoms of avoidance, re-experiencing, hyperarousal, and changes to cognition and mood that develop after an event associated with a real or perceived threat. A diagnosis of PTSD requires a persistence of symptoms one month after the initial event. Symptoms of PTSD within one month of an initial event may constitute Acute Stress Disorder (ASD). While PTSD and ASD are usually associated with events like military combat or severe accidents, they may also occur after childbirth [1]. The estimated prevalence of PTSD after childbirth is 1-2% [2, 3]. ASD and PTSD, along with other maternal mental health problems, may have a negative impact on maternal–infant relationships [4], and infant behavior and development [5]. Additionally, PTSD is a risk factor for of suicide, a leading non-obstetric cause of perinatal maternal mortality [6, 7].

An emergency team response (ETR) is the rapid assembly of a multidisciplinary team in response to an emergency. ETR systems have been advocated by several organizations, including the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Institute of Medicine, based on evidence that team training and synchronized team behaviors improve patient safety and reduce errors [8, 9, 10, 11]. Toward these safety goals, many hospitals that provide maternity care implement a code system in which teams of maternal and fetal experts respond to obstetrical and fetal emergencies. However, the unintended consequence of ETR may be increased risk for postpartum ASD or PTSD.

Known risk factors for postpartum ASD or PTSD include subjective distress during labor, emergency cesarean deliveries and instrumental vaginal deliveries, infant complications, lack of social support during labor and delivery, psychological difficulties in pregnancy, and previous traumatic experiences [2, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18]. To our knowledge, ETR during labor and delivery has not been identified as a risk factor for postpartum ASD and PTSD. Understanding the relationship between ETR and ASD or PTSD could help health providers target high-risk women for postpartum care and support. Alternatively, a lack of a relationship between ETR and ASD or PTSD symptoms could mean that formalized code calls during the childbirth experience are distinct from other types of traumatic birth. If this is the case, then identifying why women could experience formal emergency events during childbirth without increased risk for ASD and PTSD symptoms would add to the understanding of factors that mitigate postpartum ASD and PTSD.

The primary purpose of this pilot prospective study was to evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of a study protocol aimed at determining the relationship between ETR and psychological distress (i.e. ASD and PTSD symptoms). The secondary aims were to examine trends for associations between ETR and psychological distress and to calculate a sample size for a fully powered study that examines this relationship.

Methods

Institutional Review Board approval was given for this prospective observational cohort study. Convenience sampling was used for women admitted for a labor and delivery encounter at a high volume, urban, tertiary care referral birth center in the northeast United States, between June 6, 2016 and July 1, 2016 for labor and delivery. Women were approached on postpartum day 1. Cases were identified if they had an emergency team response (ETR) called during their labor and delivery. At our institution, ETR is generally activated during labor: if there are signs of fetal distress potentially necessitating expeditious management in an operating room; in cases of maternal distress; during shoulder dystocia. Controls were identified as those who had delivered within the same 24-hour time period as the cases identified, but who did not have an ETR activated during their labor. Exclusion criteria were inability to provide informed consent, lack of email address as this was the primary mode of instrument delivery and measurement, and patients who received care for non-viable fetuses as they are generally not considered candidates for ETR.

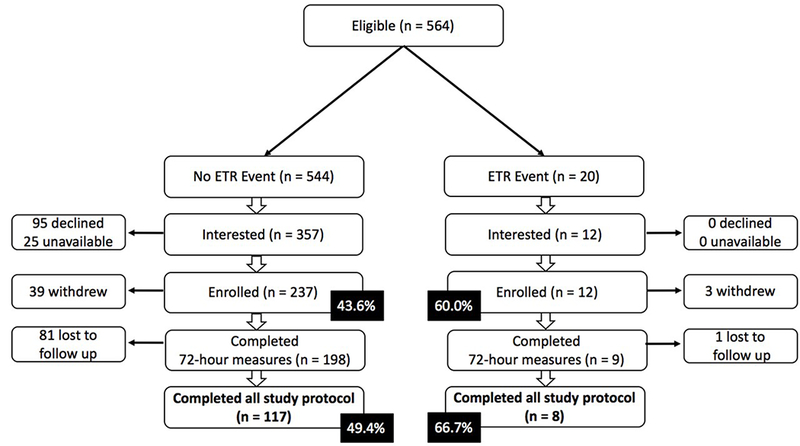

During the recruitment period, investigators prepared a list of eligible potential participants daily. Lists were distributed to health unit coordinators, who then coordinated with the patient care team to ask these patients if they were interested in learning about the research study. Patients who expressed interest were approached by a member of the study team. Participants were enrolled in the study after informed consent. Data was collected at two time points: 1) during the hospital stay within 72 hours postpartum; and 2) six weeks postpartum (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Enrollment and retention of participants. ETR, emergency team response

Within 72 hours postpartum:

Participants filled out five electronic questionnaires; the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) [19, 20]; an evaluation of social support (Social Provisions Scale, SPS) [21, 22]; a measurement of ASD symptoms (the Stanford Acute Stress Reaction Questionnaire, SASRQ) [23]; and a short questionnaire of demographic data and psychiatric history. Participants could fill out the questionnaires on a tablet provided by the study team or on their own devices via a link sent by email that was tagged with a unique identifier. Most participants were able to complete the questionnaires in 30-45 minutes. Participants were encouraged to complete questionnaires immediately after enrollment, but the protocol allowed for them to be completed anytime within 72 hours of birth, even if this was after discharge.

At six weeks postpartum:

Participants received an automatically generated email with a link to two additional electronic questionnaires, a validated and accepted PTSD screening tool (PTSD Check List-Civilian, PCL) [24] and a validated assessment of subjective distress (Impact of Events Scale, IES) [25]. Score ranges for PCL-C are 17 to 85 with a positive screen for civilian populations considered at PCL cut-points of 30-35. Score ranges for IES are 0 to 88 with a positive screen considered at a score greater than or equal to 24. If participants did not complete the questionnaires within 24 hours, the system automatically sent daily reminder emails for up to four days. If participants still did not complete their questionnaires, they received up to two reminder phone calls confirming receipt of email and asking if they still wanted to participate. If participants had not completed the questionnaires within seven days, they were categorized as lost to follow-up.

Data were also gathered from patients’ medical charts. This included details of ETRs if applicable and additional data that could influence the risk for PTSD or ASD, including episiotomy, perineal lacerations, use of instruments to assist vaginal birth, maternal or infant injury, fetal/infant co-morbid disease or anomaly, need for neonatal intensive care unit admission, infant 1-minute and 5-minute Apgar scores, past medical history, as well as demographic data such as age and previous number of pregnancies. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at our institution [26]. REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies, providing 1) an intuitive interface for validated data entry; 2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; 3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and 4) procedures for importing data from external sources.

Statistical analysis

The preliminary analysis compared the risk of ASD and PTSD symptoms among women who experienced an ETR and women who did not experience an ETR. A non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test was done to evaluate if there was a significant difference in scores on the SASRQ, PCL, or IES. A P-value of < 0.05 was required to reject the null hypothesis. The purpose of gathering data on confounders (e.g. maternal or infant injury, neonatal intensive care unit admission, episiotomy, etc.) was to assess feasibility of this data abstraction for multivariable logistic regression analysis in a fully powered study, but this analysis was not performed during this pilot phase with anticipated limited case numbers. Sample size calculations for a fully powered study were determined based on IES and PCL score means and variances/standard deviations with a priori specified effect size as detailed below (2-tailed α = 0.05, 80% power).

Results

Baseline characteristics of the sample are included in Table 1. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between ETR and non-ETR groups. Obstetric and birth characteristics were not different between groups. Enrollment and retention rates are included in Figure 1. A total of 564 women were eligible for enrollment during the study period. Of those, 369 agreed to being approached to learn more about the study. Ultimately, 249 were enrolled in the study, with the remainder either declining to participate or unavailable to be approached (e.g. not in room, did not wish to be disturbed, discharged before they were able to be approached, etc.). Of those who enrolled, 207 completed the questionnaires of the first time point with 125 going on to complete the questionnaires of the second and final time point (50.2% overall retention rate). During the study period, there were 20 women who required an ETR, an event rate of 3.5%. Of those 20, 12 agreed to be approached and all 12 were enrolled in the study. Nine completed the questionnaires of the first time point with 8 going on to complete the entire study (66.7% retention).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants

| No ETR (n=198) | ETR (n=9) | Total | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | ||||

| White | 171 [86.4] | 8 [88.9] | 179 [86.5] | 1.00 |

| African American | 25 [2.6] | 0 [0] | 25 [12.1] | 0.60 |

| Native American | 4 [2] | 0 [0] | 4 [1.9] | 1.00 |

| Asian | 2 [1] | 1 [11.1] | 3 [1.4] | 0.13 |

| Pacific Islander | 0 [0] | 0 [0] | 0 [0] | -- |

| Other | 3 [1.5] | 0 [0] | 3 [1.4] | 1.00 |

| Ethnicity | 0.13 | |||

| Hispanic/Latino | 2 [1] | 1 [11.1] | 3 [1.4] | |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 196 [99] | 8 [88.9] | 204 [98.6] | |

| Marital status | 0.77 | |||

| Single, never married | 47 [23.7] | 1 [11.1] | 48 [23.2] | |

| Married or partnered | 144 [72.7] | 8 [88.9] | 152 [73.4] | |

| Widowed | 1 [0.5] | 0 [0] | 1 [0.5] | |

| Divorced | 4 [2] | 0 [0] | 4 [1.9] | |

| Separated | 2 [1] | 0 [0] | 2 [1] | |

| Highest level of education | 0.40 | |||

| Some high school | 4 [2] | 0 [0] | 4 [1.9] | |

| High school grad or GED | 33 [16.7] | 0 [0] | 33 [15.9] | |

| Some college | 20 [10.1] | 1 [11.1] | 21 [10.1] | |

| Trade/technical/vocational | 9 [4.5] | 1 [11.1] | 10 [4.8] | |

| Associate degree | 19 [9.6] | 1 [11.1] | 20 [9.7] | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 54 [27.3] | 4 [44.4] | 58 [28] | |

| Master’s degree | 40 [20.2] | 1 [11.1] | 41 [19.8] | |

| Professional degree | 5 [2.5] | 1 [11.1] | 6 [2.9] | |

| Doctorate degree | 14 [7.1] | 0 [0] | 14 [6.8] | |

| Family income | 1.00 | |||

| Less than $24,999 | 33 [16.7] | 1 [11.1] | 34 [16.4] | |

| $25,000 to $49,999 | 39 [19.7] | 2 [22.2] | 41 [19.8] | |

| $50,000 to $99,999 | 62 [31.3] | 3 [33.3] | 65 [31.4] | |

| $100,000 or more | 64 [32.3] | 3 [33.3] | 67 [32.4] | |

| Planned pregnancy | 66 [33.3] | 3 [33.3] | 69 [33.3] | 1.00 |

| Prior traumatic delivery | 31 [15.7] | 1 [11.1] | 32[15.5] | 1.00 |

| History of anxiety | 56 [28.3] | 1 [11.1] | 57 [27.5] | 0.45 |

| History of depression | 51 [25.8] | 0 [0] | 51 [24.6] | 0.12 |

| History of PTSD | 15 [7.6] | 0 [0] | 15 [7.2] | 1.00 |

| History of sexual abuse | 22 [11.1] | 1 [11.1] | 23 [11.1] | 1.00 |

| History of physical assault | 26 [13.1] | 0 [0] | 26 [12.6] | 0.61 |

| Witnessed severe injury/death | 49 [24.7] | 2 [22.2] | 51 [24.6] | 1.00 |

| Been in a natural disaster | 8 [4] | 0 [0] | 8 [3.9] | 1.00 |

| Been in a serious accident | 15 [7.6] | 2 [22.2] | 17 [8.2] | 0.16 |

| Age | 29.95 (5.1) | 28.22 (4.2) | 29.88 (5.0) | 0.34 |

| Gravidity | 2.22 (1.5) | 2.11 (1.5) | 2.21 (1.5) | 0.72 |

| Term deliveries | 0.78 (1.0) | 0.44 (0.5) | 0.76 (1.0) | 0.44 |

| Preterm deliveries | 0.13 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 0.12 (0.4) | 0.29 |

| Abortions/miscarriages | 0.30 (0.7) | 0.67 (1.7) | 0.31 (0.8) | 0.76 |

| Living children | 0.89 (1.1) | 0.44 (0.5) | 0.87 (1.1) | 0.26 |

| Gestational age | 39 (1.6) | 38 (3.4) | 39 (1.7) | 0.88 |

Data are reported as mean (standard deviation) or frequency [%]

ETR, emergency team response; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; GED, general educational diploma

There was no difference between groups for ASD scores (median SARQ score ETR group, 4; median SARQ score non-ETR group, 4; P = 0.94) (Table 2). Symptoms of distress were higher in the ETR group (median IES score ETR group, 16; median IES score non-ETR group, 2; P = 0.084). PTSD scores were also higher in the ETR group (median PCL score ETR group, 23; median IES score non-ETR group, 20; P = 0.083). (Table 2).

Table 2.

ASD and PTSD symptom scores by ETR group.

| SASRQ (ASD) | IES (PTSD) | PCL (PTSD) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Median | IQR | P-value | N | Median | IQR | P-value | N | Median | IQR | P-value | |

| ETR | 9 | 4 | 2 - 5 | 0.94 | 8 | 16 | 1 - 21 | 0.08 | 8 | 22.5 | 20.5 - 29.5 | 0.08 |

| No ETR | 198 | 4 | 1 - 10 | 119 | 2 | 0 - 10 | 117 | 20 | 17 - 27 | |||

ASD, acute stress disorder; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; ETR, emergency team response; SASRQ, Stanford Acute Stress Reaction Questionnaire; IES, Impact of Events Scale; PCL, PTSD Checklist, IQR, interquartile range

Sample size calculation

Based on our data, a sample size of 90 (45 exposed to ETR, 45 non-exposed) is estimated to detect a 6-point difference between ETR groups for the outcome of subjective distress measured by IES, with 80% power and significance level alpha = 0.05. A sample size of 66 (33 in each group) is needed to detect a 5-point difference in PCL score between ETR groups, a difference that we considered clinically meaningful (80% power and significance level alpha = 0.05) [27]. Based on volume, recruitment and retention rates at our institution, it would require 5 months to enroll sufficient participants to detect a difference in PTSD outcome using the PCL measurement tool. Adjustments to this sample size and time frame should be made for planned multivariable regression analysis using conventional 10 events per adjusted variable [28].

Discussion

The acceptability and feasibility of this protocol design for evaluating the relationship between ETR and postpartum PTSD and ASD was evaluated. The methodology was moderately feasible and acceptable to participants and providers. Of eligible women, about 50% enrolled and about 50% completed the entire protocol. This data indicates unavoidable sampling biases inherent in observational research focused on vulnerable populations and highlights a need for methodology that addresses these biases.

Our preliminary data suggests a relationship between ETR and PTSD symptoms. Although the relationship in this small sample did not reach statistical significance at the conventional 0.05 level, a clear trend is observed, highlighting the importance of additional research. The sample size was not sufficient for regression analysis including confounders; however, future investigations can use this data to design a study in a larger target population that enables propensity score matching or regression analysis accounting for these factors.

Interestingly, although this data suggests a relationship between ETR and PTSD, it does not support a relationship between ETR and ASD symptoms. There are a few potential explanations for these findings. For some women, the physical and emotional toll of childbirth can be emotionally traumatic enough to trigger PTSD [29, 30, 31, 32], and for many women the childbirth experience may have been emotionally taxing enough to make ASD scores similar across women, regardless of ETR events. Further, between 4-13% of traumatic event survivors do not get ASD in the first month but will get PTSD in later months or years [33, 34]. It is possible, although untested in the current study, that ETR-related trauma during childbirth is unique because it is acutely experienced as “acceptable” in the interest of optimizing maternal and fetal outcomes, and thus undetectable by ASD screening, but subsequently manifests as PTSD much later. Indeed, it has been suggested that ASD screening is a means of identifying individuals who require “immediate” attention and treatment, rather than a means of identifying people at risk for developing PTSD [35]. In this way, ETR-related trauma may be a nidus of delayed negative psychiatric symptoms, as opposed to a trigger for acute symptoms.

This study had limitations. There was a relatively low frequency of ETR events, which will make it challenging to enroll a large sample. Additionally, there may have been a sampling bias. A higher proportion of participants who experienced an ETR enrolled in and completed the study compared to the non-ETR group. This observation may be explained by a more highly motivated cohort among the ETR group to assist in research investigating traumatic events. Because this study was not blinded, recruitment and enrollment could have been implicitly different for ETR participants, despite every effort of to approach each potential participant in a consistent manner. Another limitation is that the outcomes of this study are not a clinical diagnosis. The gold standard for diagnosing PTSD is a structured clinical interview by a trained clinician, which was not feasible in this study methodology due to a lack of available resources. Finally, no definitive conclusions about causality between ETR & PTSD can be made from this study given its observational design. A future regression analysis in a fully powered study that accounts for factors such as baseline anxiety or depression, acute stress symptoms, social support, history of traumatic experiences, other history of psychiatric co-morbidity, obstetric and birth characteristics, and neonatal characteristics will enable stronger conclusions to be drawn about whether ETR is an independent risk factor for PTSD. Finally, we are not able to describe characteristics of women who declined approach, or who declined enrollment after approach. One might surmise that these women may have been at higher risk for ASD or PTSD as these vulnerable populations are less likely to be open to disclosing sensitive information. For example, screening studies for mental health outcomes by self-report have noted the potential for recall and reporting biases; other studies on similarly sensitive subjects such as intimate partner violence have noted the potential for reporting bias due to stigma [36, 37].

In summary, this pilot study demonstrated moderate feasibility and acceptability of a prospective cohort study methodology that evaluates the relationship between ETR and postpartum subjective distress and PTSD. Methods that emphasize sensitivity to the unique concerns of these vulnerable populations are needed. A relationship between ETR and PTSD appears to exist. The effect of ETR on postpartum psychological distress remains a significant clinical question given the impact on maternal and infant well-being.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The project described was supported by the National Institutes of Health through Grant Numbers UL1TR001857 and K12HD043441.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimers

The views expressed in the submitted article are the authors own and not an official position of the institution or funder.

Disclosure of Interest

The authors report no financial conflicts of interest

References.

- 1.Alcorn KL ODA, Patrick JC, Creedy D, Devilly GJ. A prospective longitudinal study of the prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder resulting from childbirth events. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40(11):1849–59. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersen LB, Melvaer LB, Videbech P, et al. Risk factors for developing post-traumatic stress disorder following childbirth: a systematic review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2012. November;91(11):1261–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2012.01476.x PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ayers S, Joseph S, McKenzie-McHarg K, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder following childbirth: current issues and recommendations for future research. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2008;29(4):240–250. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ayers S, Eagle A, Waring H. The effects of childbirth-related posttraumatic stress disorder on women and their relationships: a qualitative study. Psychol Health Med 2006;11:389–398. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaw R, Bernard R, Deblois T, et al. The relationship between acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder in the neonatal intensive care unit. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:131–137. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kessler R Posttraumatic stress disorder: the burden to the individual and to society. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(Suppl 5):4–14. PubMed PMID: . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Furuta M, Sandall J, Bick D. A systematic review of the relationship between severe maternal morbidity and post-traumatic stress disorder. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;10(12):125 PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Committee on Patient Safety and Quality Improvement. Preparing for Clinical Emergencies in Obstetrics and Gynecology. Committee Opinion Number 590 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kohn L, Corrigan J, Donaldson M. To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merién A, van de Ven J, Mol B, et al. Multidisciplinary team training in a simulation setting for acute obstetric emergencies: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(5):1021–1031. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality Health Care in America. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garthus-Niegel S, Knoph C, von Soest T, et al. The role of labor pain and overall birth experience in the development of posttraumatic stress symptoms: a longitudinal cohort study. Birth. 2014;41(1):108–115. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garthus-Niegel S, von Soest T, Vollrath M, et al. The impact of subjective birth experiences on post-traumatic stress symptoms: a longitudinal study. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2013;16(1):1–10. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lev-Wiesel R, Chen R, Daphna-Tekoah S, et al. Past Traumatic Events: Are They a Risk Factor for High-Risk Pregnancy, Delivery Complications, and Postpartum Posttraumatic Symptoms? Journal of Women’s Health. 2009;18(1):119–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rowlands I, Redshaw M. Mode of birth and women’s psychological and physical wellbeing in the postnatal period. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12(138). PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shlomi Polachek I, Dulitzky M, Margolis-Dorfman L, et al. A simple model for prediction postpartum PTSD in high-risk pregnancies. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2015;19(3):483–490. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vossbeck-Elsebusch A, Freisfeld C, Ehring T. Predictors of posttraumatic stress symptoms following childbirth. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;16(14):200 PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wijma K, Soderquist J, Wijma B. Posttraumatic stress disorder after childbirth: a cross sectional study. J Anxiety Disord 1997;11:587–559. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spielberger C State-Trait Anxiety Inventory: Bibliography (2nd ed.). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spielberger C, Gorsuch R, Lushene R, et al. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cutrona C, Russell D. Social Provisions Scale (SPS): The provisions of social relationships and adaptation to stress In: Jones W, Perlman D, editors. Advances in personal relationships. Vol. 1 Greenwich, CT: JAI Press; 1987. p. 37–67. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gottlieb B, Bergen A. Social support concepts and measures. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2010;69(5):511–520. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cardena E, Koopman C, Classen C, et al. Psychometric properties of the Stanford Acute Stress Reaction Questionnaire (SASRQ): a valid and reliable measure of acute stress. J Trauma Stress. 2000. October;13(4):719–34. doi: 10.1023/A1007822603186 PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weathers F, Litz B, Herman D, et al. The PTSD Checklist: Reliability, validity, & diagnostic utility Annual convention of the international society for traumatic stress studies, San Antonio, TX: 1993;462. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weiss D, Marmar C. The impact of event scale – revised In: Wilson J, Keane T, editors. Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD. New York: Guilford Press; 1997. p. 399–411. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harris P, Taylor R, R T, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Monson C, Gradus J, Young-Xu Y, et al. Change in posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: Do clinicians and patients agree? . Psycholgical Assessment. 2008;20(2):131–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vittinghoff E, McCulloch C. Relaxing the rule of ten events per variable in logistic and Cox regression. Am J Epidemiol 2007;165:710–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Czarnocka J, Slade P. Prevalence and predictors of post-traumatic stress symptoms following childbirth. Br J Clin Psychol. 2000. March;39 ( Pt 1):35–51. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allen S A qualitative analysis of the process, mediating variables and impact of traumatic childbirth. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 1997. December;16(2–3):107–31. doi: 10.1080/02646839808404563. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ballard CG, Stanley AK, Brockington IF. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after childbirth. Br J Psychiatry. 1995. April;166(4):525–8. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boorman RJ, Devilly GJ, Gamble J, et al. Childbirth and criteria for traumatic events. Midwifery. 2014. February;30(2):255–61. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. PTSD: National Center for PTSD. Acute Stress Disorder. Available from: www.ptsd.va.gov/public/problems/acute-stress-disorder.asp Accessed on 7/30/2018. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cahill SP, Pontoski K. Post-traumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder I: their nature and assessment considerations. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2005. April;2(4):14–25. PubMed PMID: . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bryant RA. Acute stress disorder as a perdictor of posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011. February;72(2):233–9. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chang JC, Cluss PA, Burke JG, et al. Partner violence screening in mental health. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2011. Jan-Feb;33(1):58–65. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stark L, Sommer M, Davis K, et al. Disclosure bias for group versus individual reporting of violence amongst conflict-affected adolescent girls in DRC and Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2017. April 4;12(4):e0174741 PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]