Abstract

Commercial interests have long been identified as a macrosocial determinant of health. We present a composite indicator of corporate permeation- the Corporate Permeation Index (CPI) -, a novel tool for explaining variations in the consumption of products such as alcohol or tobacco and in the comprehensiveness of health policy regarding these products.

Using a published framework for the analysis of commercial influences on health as a theoretical basis, we collected 25 indicators of corporate permeation comparable across 148 countries in five continents for six years 2010–2015. Two alternative approaches were used in each of the steps taken to build the measure – imputation of missing data, multivariate analysis, and weighing and aggregation of the subcomponents. We assessed the Index’s criterion-related validity by calculating the strength of the association among the different formulations of the Index.

Alternative formulations of the CPI are highly correlated. Whilst High Income Countries are generally overrepresented among the lowest scores, some High Income Countries have high permeation scores. There is no clear regional pattern, with scores showing as much intra-regional as inter-regional variability.

The CPI appears to be a robust measure of corporate permeation at the national level, suggesting tremendous variability in permeation worldwide. There are limitations to the CPI, the most notable of which is the lack of large scale cross-country comparable data on some important mechanisms of corporate permeation (e.g., lobbying expenditures by large corporations). Further work will target proxy measures for these phenomena to be incorporated in the Index calculation.

Keywords: Commercial determinants of health, Macrosocial Determinants of Health, Non Communicable Diseases, Corporate power

Introduction

Corporate permeation refers to the extent to which corporations penetrate all aspects of society, from macrosocial and political aspects, such as corporate donations to election campaigns (Jorgensen, 2013), to shaping individual consumption patterns, through, for example, advertising that encourages eating calorie-dense, nutrition poor foods at fast food chains (Siddique, 2017). Corporate permeation does not measure whether corporate presence in a given society is positive or negative but rather, measures the extent to which corporations are embedded in the political, legal, social, economic and cultural fabric of a country. Corporate permeation, like corporate power, “is a capacity [authors’ emphasis] not the exercise of that capacity (it may never be, and never need to be exercised)” (Lukes, 2005).

This capacity often relies on collusion between both the private and the public sector. Where the rules of the game -laws, and institutions - have been shaped to benefit vested interests, corporate influence may be entirely legal, even if it adversely affects public health outcomes (Mindell et al., 2012). Accordingly, vested interests that remove public policy from the realm of democratic, contestable decision making should be taken into account by measures gauging undue corporate capture of the public sector. Kauffman proposes the term “privatization of public policy” (Kauffmann, 2004, Kauffmann and Vicente, 2011) to describe this phenomenon. Furthermore, vested interests may be drivers of undue corporate influence. Using a cross-country dataset, Wu found that low corporate governance standards have an important role in the supply side of undue corporate behaviour (versus the demand side whereby public officials offer to incur in wrongdoing) (Wu, 2005). For example, in their study of the influence of transnational tobacco companies (TTC) on social policy, Holden and Lee point out how TTC derive structural power in their relationships with states from integrated supply chains and the opportunities to exit from any given national economy (Holden & Lee, 2009), this enables corporations to punish and reward countries for their policy choices (Fuchs, 2005). The reward and punishment may erode even the sturdiest of institutional governance systems. Countries such as the United States (US) or Germany may score highly on indicators of institutional governance merely because reward and punishment systems– e.g. the magnitude of campaign donations from industry and revolving doors between the public and private sectors - are not incorporated into popular tools such as Transparency International’s Perceptions of Corruption Index. Despite their high institutional governance scores, both countries have documented histories of tight relationships between industry and regulators leading to institutional erosion as evidenced by the current state of gun control legislation in the US (Langbein and Lotwis, 1990, Gambino, 2018, Spies, 2018) or the car emissions revelations in Germany in 2015 (Barkin , 2015, Hotten, 2015).

We present the Corporate Permeation Index, a composite indicator of the degree to which corporate power is embedded in the social, political and cultural fabric of a country. The CPI intends to be a tool for academics, public health practitioners and advocates to explain variations in the consumption of products such as alcohol or tobacco and in the comprehensiveness of health policy regarding these products, in individual countries over time and across different countries.

A composite indicator is likely the most suitable tool to quantify a complex concept such as corporate permeation because most often commercial interests deploy myriad tactics to promote their products (Brownell and Warner, 2009, Mccambridge et al., 2014, Mialon et al., 2015). For example, in the 1960s the sugar industry funded research highlighting saturated fat as a major contributor to cardiovascular disease (Kearns, Schmidt, & Glantz, 2016). As a result, the medical community and public at large became concerned with the nefarious effects of saturated fat on cardiovascular health, while sugar’s equivalent contributions remain largely ignored. This has implications on medical advice regarding lifestyle and on product regulation. The discourse on the health effects of sugar consumption puts pressure on legislators to, for example, subsidize sugar crops to bring sugar prices down, increasing availability (Siegel et al., 2016). At the same time, industries funnel their energy into public health solutions that will not impact their profits. The sugar industry funds organisations that advise increased physical activity to combat childhood obesity to the detriment of policies that curtail exposure to obesogenic foods (Serôdio, McKee, & Stuckler, 2018). Last but not least, industries employ these tactics in a climate where an emphasis on personal responsibility for individual and population health increasingly limits statutory regulation of food environments (Brownell & Warner, 2009). Seemingly independent industry sponsored think tanks and media in turn fuel the personal responsibility rhetoric without disclosing industry funding or conflicts of interest (Alvy and Calvert, 2008, Simon, 2013).

The Corporate Permeation Index (CPI) is the quantitative expression of theoretical concepts organised in the framework proposed by Madureira Lima and Galea (Madureira Lima & Galea, 2018) to guide the study of corporate practices that influence the health of populations. We used the categories the authors call “Vehicles of [Corporate or Commercial] Power”- the Political Environment, Preference Shaping, Knowledge Environment, Legal Environment, and Extra Legal Environment- and the corresponding “Practices of Power” —the tactics that enable corporate power—to guide the selection of indicators. The first category quantifies the Vehicles of Political Environment: it covers national regulations on party, campaign, and election financing, trade related indicators and factors related to how corporations interact with the public sector. The second category quantifies the Vehicle of Extra-Legal Environment: unambiguously illegal practices such as bribing. The third category quantifies the Vehicle of Legal Environment: aspects of corporate governance and corporate ethics which include practices inherent to the corporate structure, the transparency of reporting systems, and whether shareholders can hold management accountable for unethical or risky behaviours. The fourth category includes aspects of the Vehicle of Preference Shaping or explicit strategies directed at making the consumption environment more receptive to their products including increased ownership of media outlets and intensity of marketing. Some of the Practices of Power, by virtue of their unofficial nature, are impossible to quantify or to compare across countries. This is the case with lobbying expenditure, revolving doors between the public and the private sector or contributions of industry representatives to trade agreement negotiation. Where exact indicators of the Practices could not be found e.g. corporate capture of trade negotiations, proxies were found e.g. Foreign Direct Investment, tariffs, and barriers to trade.

Methods

Data selection

(Table 1A in the Annex provides a Checklist of step by step construction of a composite indicator).

Each source was evaluated against the following criteria:

-

A)

Reliable data collection and methodology from a credible institution: each source should originate from a professional institution that clearly documents its methods for data collection.

-

B)

Quantitative granularity: The scales used by the data sources must allow for sufficient differentiation in the data on the perceived or directly measured levels of corporate dominance across countries.

-

C)

Cross country comparability: As the aim is to compare countries, the source data must also be legitimately comparable between countries; the source should measure the same thing in each country scored, on the same scale.

-

D)

Multiyear data-set: Sources that capture indicators for a single point in time, but that are not designed to be repeated over time, are excluded.

This is because one of the applications of the CPI is to explain variations in the consumption of unhealthful commodities and strictness and comprehensiveness of health policy. If we don’t use comparable measures over time, the only possible design is a cross sectional one, which means that we will not be able to quantify these associations within countries, only between.

The data sources are: The World Economic Forum’s Executive Opinion Survey, International IDEA’s database on Political Finance, Political Risk Index; United Nations Conference on Trade and Development UNCTD; Freedom of the Press Index; and KOF Swiss Economic Institute. (We provide additional details in Table 2A in the Annex.).

Indicators

We selected 25 indicators of corporate permeation. We describe each indicator, its source and the rationale for inclusion in detail in Annex 2 and we provide a summary of each indicator in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of CPI indicators for 2015a.

| Variable | Observations | % Missing | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Political Environment | ||||||

| Cluster Development | 140 | 5,40% | 3,78 | 0,76 | 2,32 | 5,49 |

| Electoral Policy | 138 | 6,80% | 1,84 | 0,48 | 1,00 | 2,88 |

| Foreign Direct Investment as % of GDP | 148 | 0% | 5,30 | 11,10 | -4,13 | 100,20 |

| Foreign Ownership of Companies | 140 | 5,40% | 4,48 | 0,84 | 2,14 | 6,26 |

| Impact of Rules on FDI on Business | 140 | 5,40% | 4,45 | 0,79 | 2,05 | 6,57 |

| Inward Flows of Trade | 0 | 100% | ||||

| Market Dominance of Firms | 140 | 5,40% | 4,24 | 0,73 | 2,10 | 5,72 |

| Outward Foreign Direct Investment as % of GDP | 131 | 11,40% | 2,52 | 8,68 | -4,62 | 68,91 |

| Restrictions to Trade | 0 | 100% | ||||

| Trade Barriers | 140 | 5,40% | 4,30 | 0,49 | 2,98 | 5,63 |

| Trade Tariffs | 140 | 5,40% | 22,60 | 5,03 | 1,66 | 29,00 |

| Value Chain | 140 | 5,50% | 3,93 | 0,75 | 2,73 | 6,15 |

| Preference Shaping | ||||||

| Extent of Marketing | 140 | 5,40% | 4,34 | 0,68 | 2,41 | 6,04 |

| Freedom of the Press from Economic Interests | 148 | 0,00% | 14,26 | 5,90 | 4,00 | 27,00 |

| Legal Environment | ||||||

| Anti Monopoly Policy | 140 | 5,40% | 4,12 | 0,72 | 2,43 | 5,66 |

| Audit Reporting Standards | 140 | 5,40% | 3,35 | 0,86 | 1,42 | 5,48 |

| Efficacy of Corporate Boards | 140 | 5,40% | 3,23 | 0,66 | 1,73 | 5,60 |

| Investor Protection | 140 | 5,40% | 4,53 | 1,20 | 1,80 | 8,00 |

| Judicial Independence | 140 | 5,40% | 4,02 | 1,27 | 1,32 | 6,87 |

| Protection of Minority Shareholders | 140 | 5,40% | 3,86 | 0,76 | 1,93 | 5,53 |

| Extra Legal Environment | ||||||

| Corruption | 126 | 5,40% | 3,19 | 1,19 | 0,50 | 5,00 |

| Diversion of Public Funds | 140 | 5,40% | 4,39 | 1,20 | 1,59 | 6,78 |

| Ethical Behaviour of Firms | 140 | 5,40% | 3,89 | 0,88 | 1,70 | 5,60 |

| Favouritism of Government Officials | 140 | 5,40% | 4,76 | 0,92 | 2,35 | 6,59 |

| Irregular Payments and Bribes | 140 | 5,40% | 3,85 | 1,20 | 1,32 | 5,91 |

Authors own calculations

Normalization, missing value imputation and multivariate analysis

We used z scores to normalise the variables. To address missing values, we used multiple imputation (Allison, 2002, Schafer and Graham, 2002, Donders et al., 2006) to produce 10 imputed datasets using predicted mean matching for arbitrary patterns of missingness with three nearest neighbours. This means that we use a Stata command that specifies the number of closest observations (nearest neighbors) from which to draw imputed values. The default is to replace a missing value with the “closest” observation. The closeness is determined based on the absolute difference between the linear prediction for the missing value and that for the complete values. The closest observation is the observation with the smallest difference (Stata, no date). We created a complete dataset using conditional mean imputation as a robustness check.

Some of the 25 indicators used in the construction of the CPI are highly correlated with each other (See Table 4A in the Annex). Accordingly, it is plausible that among these 25 indicators, there are some that capture the same underlying concept. It was thus necessary to shed light on how these different indicators vary in relation to each other. We used Factor Analysis (FA) to detect the structure in the relationships between the variables (Yong & Pearce, 2013) and applied FA to each of the10 imputed datasets and extracted between 3 and 4 factors per dataset.1 The factor loadings, i.e. the correlations of the variables to the factor, seem to indicate the presence of five “underlying concepts” – Factor 1 (Public – Private Sector Governance); Factor 2 (Firms’ Commercial Strategy); Factor 3 (Trade Conditions); Factor 4 (Foreign Direct Investment); Factor 5 (Election Policies vis a vis Engagement with Corporations). These show some resemblance to those based on the theoretical framework: Political Environment, Legal Environment, Extra Legal Environment and Preference Shaping Environment. The composition of the factors was fairly constant across imputed datasets as well as in the dataset imputed using a conditional mean (Table 5.1–5.6n the Annex). The factor loadings for some variables were quite similar in two or more factors i.e. they were as important in capturing the concept underlying factor 1 as they were in capturing the concept underlying factor 2. Furthermore, the criteria for factor selection meant that more often than not, factors 4 and 5 were simply dropped. The problems that these challenges present to the validity of the Index will be addressed in subsequent sections.

Weighing and aggregation

We decided against using expert opinion based weights because they are not recommended for large numbers of indicators as they may hinder the trade-off process among the different options (OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), 2008). We decided instead to source the weights from the matrix of factor loadings after rotation. The individual indicators with the highest factors loadings are grouped into intermediate composite indicators. The resulting intermediate composites, which in this case varied from one imputed dataset to another between two and four, are aggregated by assigning each a weight equal to the proportion of the explained variance in the dataset. As for the aggregation method, we chose linear aggregation, or the summation of weighted and normalized individual indicators. This is the most widespread method of aggregation used by the most commonly used composite indicators.

The formula for the CPI is thus

Linear aggregation implies full (and constant) compensability, i.e. poor performance in some indicators can be compensated by sufficiently high values in other indicators. Weights express trade-offs between indicators: deficits in one dimension can be offset by surplus in another. When different goals are equally legitimate and important, a non-compensatory logic may be necessary (Nardo et al., 2005). We decided against compensatory methods because this would imply a judgement on the relative merits of one dimension versus another. In the case of corporate permeation where mechanisms such as the ownership of the media by corporations or the funding of science over policy decisions has not been studied exhaustively, it is nearly impossible to attribute the quantitative value to each of these tactics necessary to a non-compensatory approach.

Uncertainty analysis

Because the various components of the CPI construction process can introduce uncertainty into the output, we calculated six alternative formulations varying the type of imputation (multiple imputation and conditional mean imputation) and the type of multivariate analysis (FA Weighing; FA Equal Weighing and Equal Weighing). Each of the six formulations were arbitrarily assigned a letter to distinguish them. Formulations A, AA and B use multiple imputation and Z-scores and FA Weighing, FA Equal Weighing and Equal Weighing, respectively. Formulations E, EE and F use conditional mean imputation and and FA Weighing, FA Equal Weighing and Equal Weighing, respectively. The six formulations are highly correlated (Table 6A in the Annex).

Results

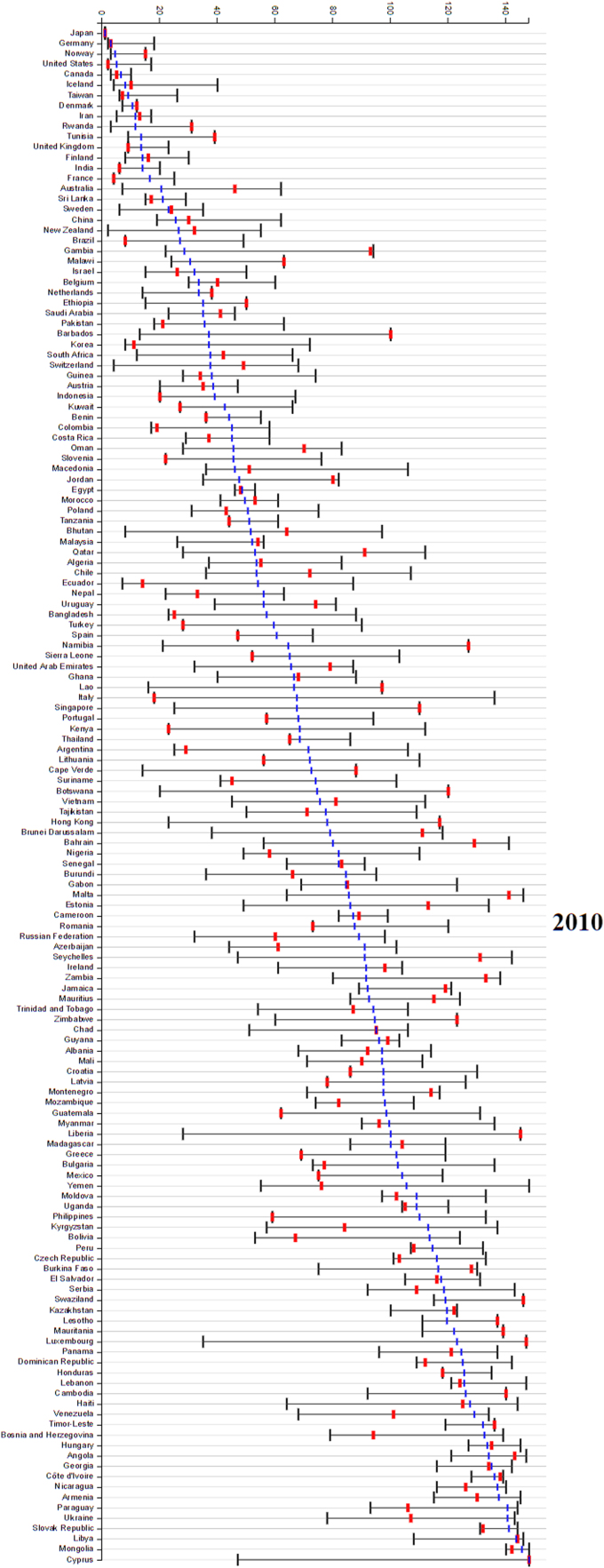

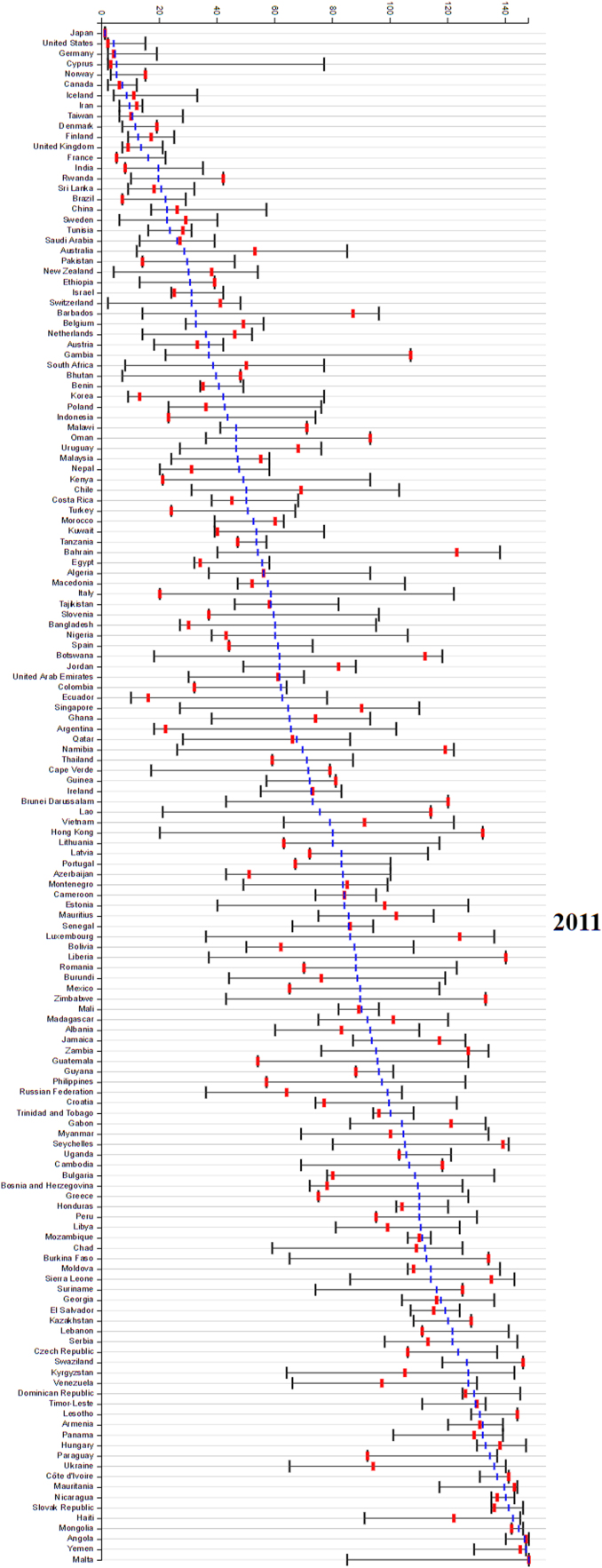

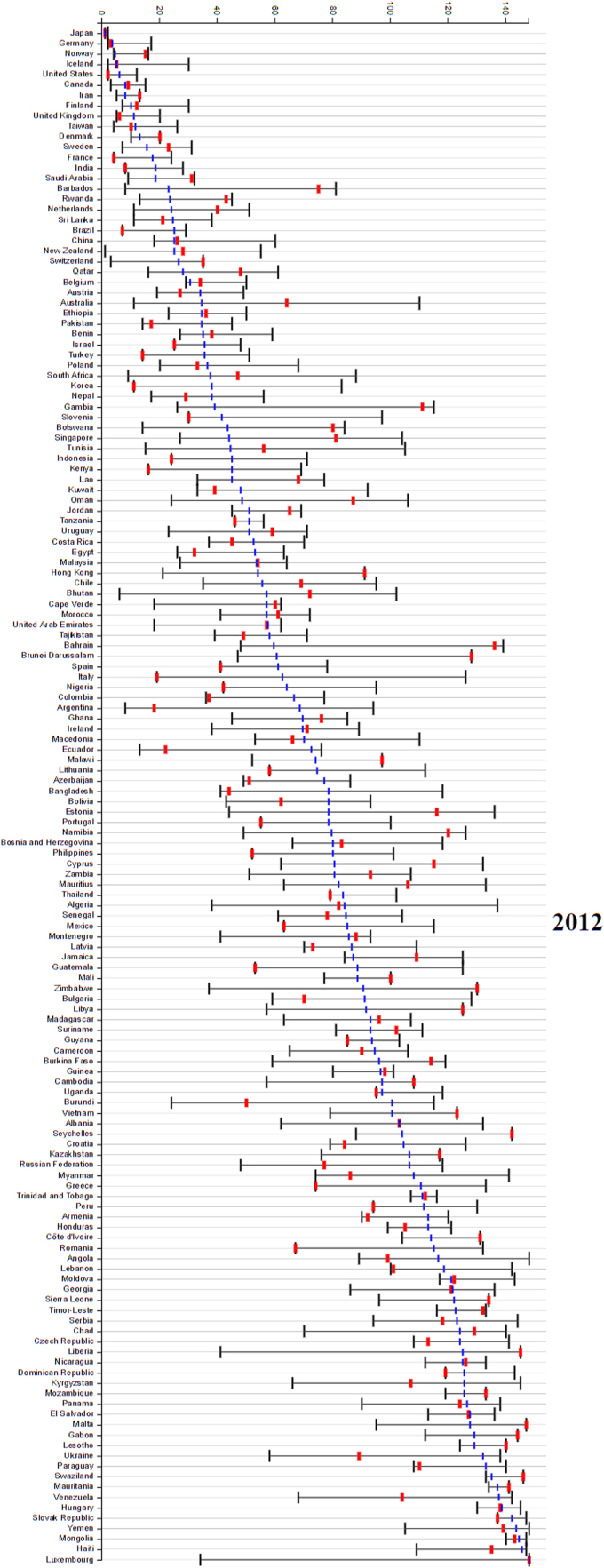

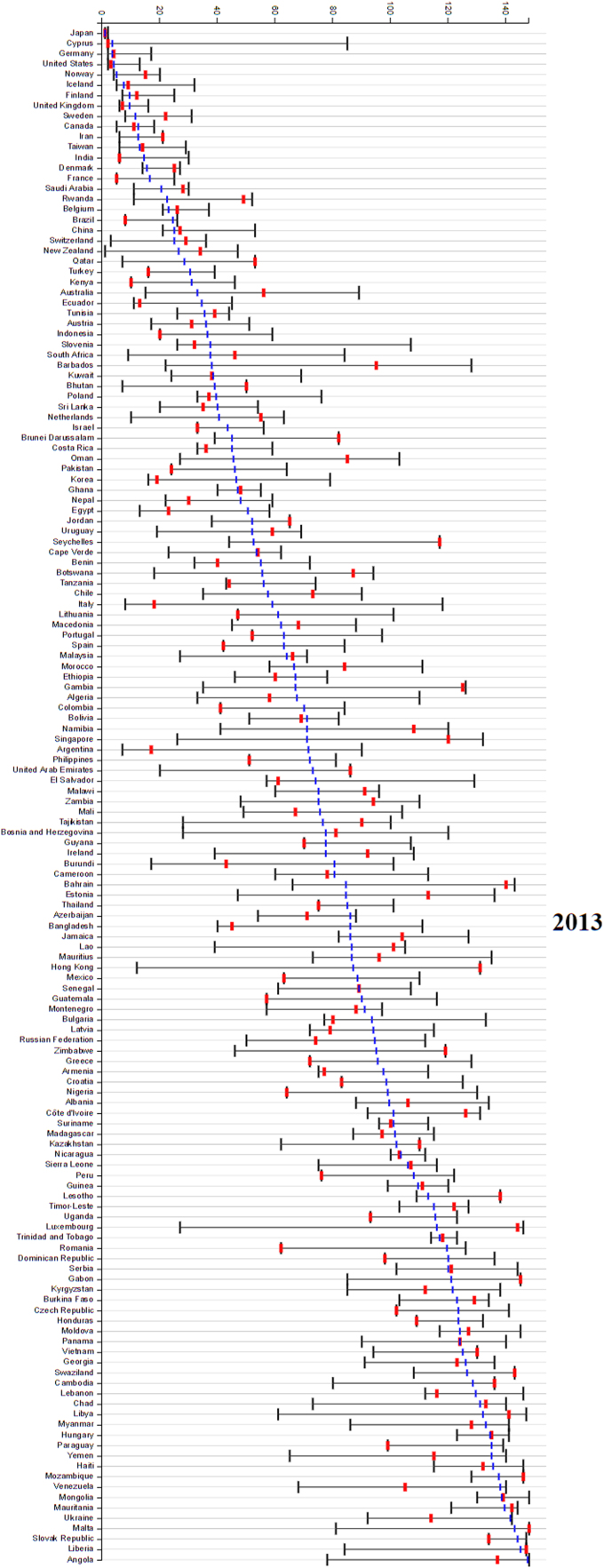

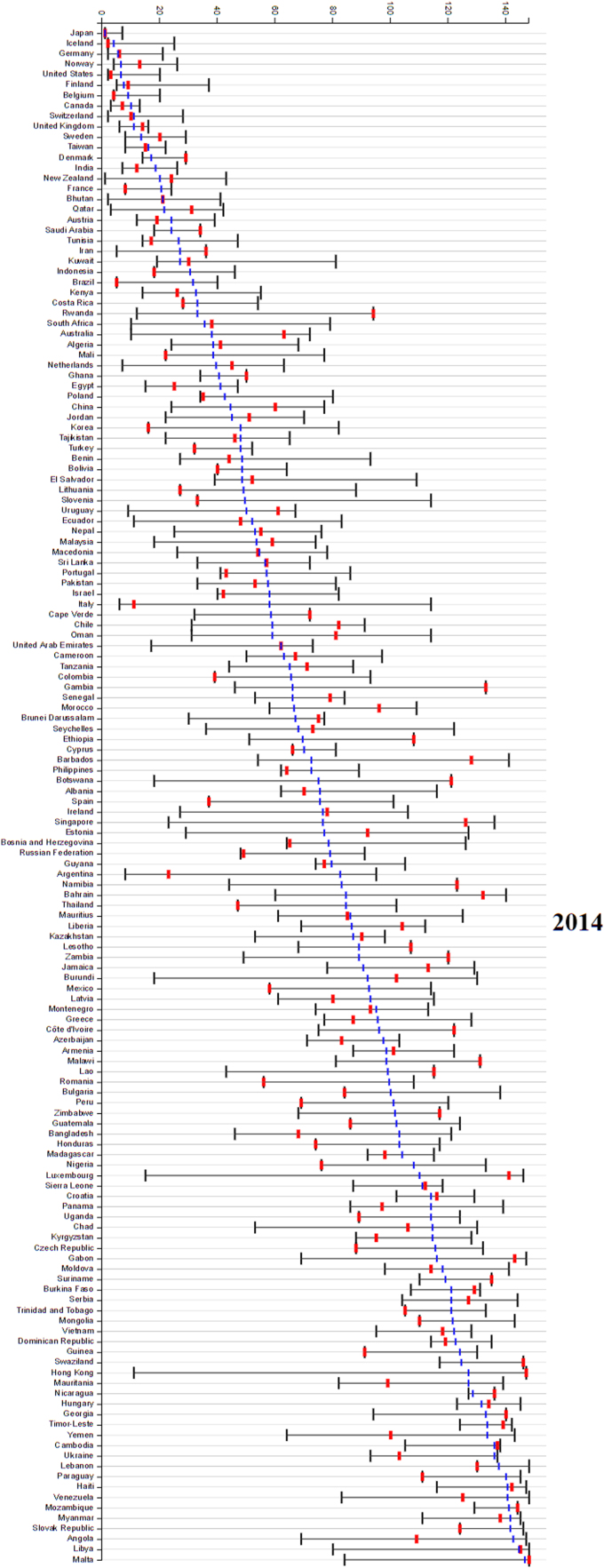

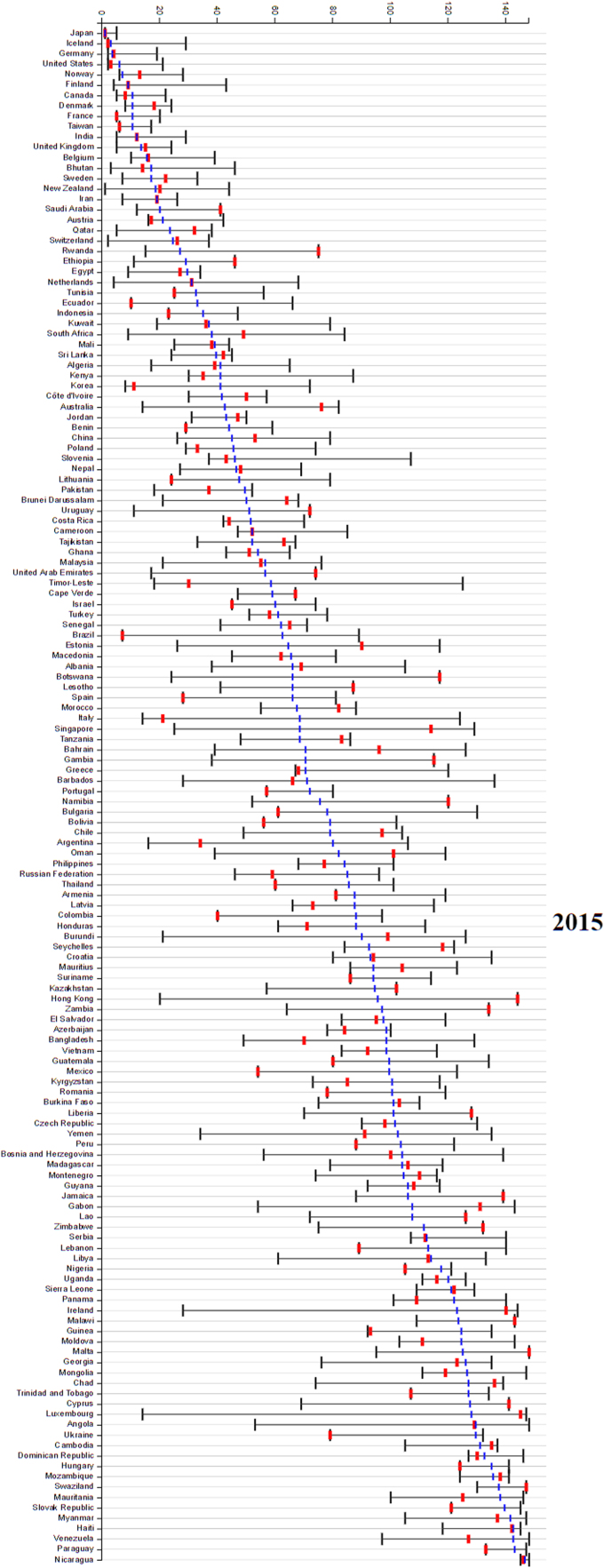

Graph 1, Graph 2, Graph 3, Graph 4, Graph 5, Graph 6 show the rankings for all six index formulations. The yellow rectangle represents the median of all scores obtained with different formulations and the red rectangle represents the score obtained with the EE formulation (equal weighing) (Graph 1, Graph 2, Graph 3, Graph 4, Graph 5, Graph 6). Countries are ordered according to the median of all scores, from the lowest to the highest.

Graph 1.

Graph 2.

Graph 3.

Graph 4.

Graph 5.

Graph 6.

In order to better understand the CPI, we focus here on countries in the fourth and first quartile of corporate permeation (calculated after ranking the countries by the median of the value of each formulation), discussing the countries in each quartile and the extent to which the CPI captures realities.

First quartile – low corporate permeation

The top quartile of countries with low corporate permeation comprises the 30 lowest ranking countries. Within the first quartile, in 2010 for example, Japan shows the lowest permeation and Saudi Arabia the highest (Graph1 1in the Annex). Although high-income countries are overrepresented in the first quartile of ranked countries, they are also represented in the fifth quartile.

Fourth quartile, high permeation index

The fourth quartile of the permeation index is populated with countries from across the development and geographic spectrum. It is an interesting finding that the high-income countries among the highest ranks are tax havens –Luxembourg, Malta, Cyprus, Ireland (in some years).

The geographic distribution of corporate permeation does not reflect regional lines; within some regions, median scores vary tremendously. In fact, we find more intraregional variability than international variability (Table 7A in the Annex and Graphs 1.1 to 6.1).

Discussion

First quartile – low corporate permeation

Iceland features consistently in the lowest quartile for corporate permeation. This may come as a surprise, given the collapse of the country’s banking system in the early days of the 2007 financial crisis that exposed a lack of transparency and accountability in the financial services industry. We would argue, however, that the low ranks reflect how a country responded to the crisis. In other words, all CPI formulations include variables that paint a multidimensional picture of corporate power in Iceland, including the country’s response to this crisis of transparency and accountability with an independent judiciary and media. For example, while some countries like the US and France convicted low ranking financial cadres following the 2007 crisis, in Iceland, bank chief executives received convictions and jail terms. Iceland’s response in the aftermath of the financial crisis sheds light on the weak corporate permeation of its financial sector, especially when compared with other severely affected economies such as those of the European Union or the United States where brokered deals managed to avert lawsuits (Silver-Greenberg & Craig, 2014). For example, in 2013 Eric Holder, the former US Attorney-General, explained his reticence to prosecute large banks:

“When we are hit with indications that if you do prosecute, it will have a negative impact on the national economy, perhaps even the world economy.” (Milne, 2016).

He later backtracked but, so far, no chief executive at a big US or European bank has been prosecuted in the aftermath of the collapse of the financial sector ten years ago.

Iceland’s attitude towards international financial institutions highlights the limits of corporate permeation of the banking and financial services sector. The International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) rescue package prescribed that the Icelandic Government would assume liability for the banks’ losses, which would have resulted in 50% of the national income between 2016 and 2023 being paid to the UK and Dutch Governments. The Icelandic president refused to approve the deal stating:

“Ordinary people, farmers and fishermen, taxpayers, doctors, nurses, teachers, are being asked to shoulder through their taxes a burden that was created by irresponsible greedy bankers” - President Olafur Ragnar Grimsson (The New York Times, 2010).

While, arguably, the CPI may be trusted to portray limited corporate permeation in Iceland, the low-ranking positions of some other high-income countries such as the United Kingdom, who ranked 12 in 2010, is more surprising. Holden and Lee document how in the late 1990s New Labour “did not require the protestations and representations of business to place corporate interests centre stage: perceived structural pressures were enough to drive the party’s corporate centred social policy.” (Farnsworth & Holden, 2006, p. 482)

“When I last addressed the CBI’s National conference, I promised a new partnership between New Labour and business. Six months into office, we have laid the foundations of that partnership. There are business people bringing their experience and expertise by serving in Government, on Advisory Groups, leading task forces, all contributing to the success of Government policy. But there is also great commitment and enthusiasm, right across the Government, for forging links with the business community. That this is the approach of a Labour government is of historic importance. It demonstrates we are entering a new era in British politics. (Tony Blair, Speech to the CBI Conference, 11 November 1997)” (cited in Farnsworth & Holden 2006 p.481).

It is therefore plausible that the CPI fails to fully capture all aspects of corporate permeation in the UK, namely, the first two vehicles of corporate power in the corporate power framework – Political Environment and Preference Shaping. In other words, the CPI does not incorporate any variables that could feasibly measure a government’s ideological proclivity to “place corporate interests centre stage” nor does it incorporate variables that lend quantitative support to that proclivity. These include volumes of corporate donations to parties and election candidates, prevalence of revolving doors between cabinet members and business, the dominance of business representatives in advisory committees (versus a balanced representation of other social actors), funding of think tanks that take advisory roles to government and government officials owning stock in corporations and using insider information from their official roles in hearings, to personally benefit and use their influence to support corporations.

Similarly, Germany’s and the US’s relatively low positions are striking because an abundance of research documents strong ties between the corporate sector and virtually every sphere of public and private life in both countries. In the US, the ultimate expression of these ties is found in the increasing legal personification of corporations (White, 2010). Recent US Supreme Court Rulings in Citizens United and Hobby Lobby expanded corporations’ First Amendment rights. Citizens United grants corporations the right to make unlimited campaign donations, while Hobby Lobby protects corporations’ religious freedom by allowing corporate religious objections to carve out exceptions to federally mandated guarantees i.e. insurance coverage for birth-control mandated by the Affordable Care Act (Greenfield & Winkler, 2015).

It is possible that the US’s rank range from number 2 to number 30 sheds some light on this apparent dissonance between documented and quantified corporate power. The US’s highest CPI score of 30 is obtained when we attribute higher weights to Factors 1 and 2, factors that capture Public – Private Sector Governance and Firm Commercial Strategy, respectively and lower weights to factors that measure Trade Conditions, Foreign Direct Investment and Election Policies. This finding, to some extent, is consistent with the US corporate power literature as most of the empirical studies document state capture. The Factors pertaining to Trade and FDI are arguably less accurate at predicting permeation within US borders than they are in predicting permeation within the borders of US trade partners, which explains why their inclusion yields a lower ranking.

Germany’s relative low CPI rank also deserves some discussion. On one hand, low CPI ranks may be explained by the composition of the German economy. More than 99%of German companies are small and medium enterprises - in absolute figures, more than 3.6 million companies, providing more than 60 percent of all jobs (Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy, 2017). Although Germany does have some world market leaders such as Volkswagen and Siemens, they are fewer than would be expected given the size of the economy. It is plausible that the CPI questions, chosen deliberately to grasp permeation by large international conglomerates fail to capture permeation by national small and medium enterprises. On the other hand, both of Germany’s Fortune 500 corporations -Volkswagen and Siemens - have been involved in high profile corporate corruption scandals that revealed close ties between government and the corporate sector on the national and international stages (Barkin , 2015, Hotten, 2015). As it was the case with the UK, it is likely that the absence of measures of corporate donations, revolving doors, prevalence of corporate members in advisory committees, and insider trading explains part of the CPI’s failure to portray this layer of government and institutional permeation.

Bhutan is worth highlighting as a low middle-income country that consistently features among the lowest CPI ranks over the years, especially after 2013. Its score ranges are relatively narrow, lowest ranks tend to be produced by formulations that weigh all indicators equally and highest ranks by those that attribute more weight to the Public Private Governance Factor. Low scores on Factors capturing Firms Commercial Strategy, Trade Conditions and FDI are unsurprising given the country’s history of isolation. It was never colonised and it did not join the United Nations until 1971. Its broadcasting company was launched in 1973 and it was the last country in the world to introduce television in 1999. Its integration into the globalised economy has been slow – its trade and other economic relationships are, for the most part, confined to India, Bangladesh and Nepal, and a few countries outside the region. Moves towards economic liberalization have been cautious with ascension to the World Trade Organization currently underway. According to the World Bank, Bhutan’s economy remains dominated by state owned enterprises with the private sector contributing only eight percent to the national revenue (The World Bank, 2013). The country has also adopted a unique and people centred approach to its socio-economic development that promotes population wellbeing over material development making Bhutan the first country in the world to pursue happiness as a state policy (Alkire et al., 2012). The perceived extent of corruption in Bhutan is low and this is expressed consistently across different national and international survey instruments (Leon, 2015). More encompassing formulations of the CPI are thus more likely to capture this holistic approach to development and bring the country down in the permeation ranks.

India, China and Brazil’s relative low scores are interesting findings given the high incidence of corruption scandals in all three countries. The results are consistent, however, with each country’s protectionist trade policy. High levels of protectionism mean enhanced trade barriers for foreign companies, including large corporations. This is not to say that domestic companies do not attain high levels of permeation, just that the CPI is not as well equipped to detect domestic permeation. The ranges of these countries back this hypothesis. In India and in Brazil, maximum scores are obtained with calculations that attribute higher weights to Factor 1 (Public – Private Sector Governance) and lower weights to factors related to trade policies and FDI. The lowest scores are obtained with approaches that weigh all factors equally, so that the protectionist nature of their trade policy is more prominent and is translated into lower permeation.

It is worth singling out Brazil among low-ranking countries. The impeachment of Brazil’s former President on the grounds of corrupt relations, the subsequent accusations of corruption pending over half of the members of the senate, the police force, and the President who subsequently took office, may prima facie raise concerns about the plausibility of its low position. On the other hand, a closer examination of Brazil’s exercise of soft power in the international arena to defy large corporate interests and to assist other developing countries in following suit may lend some credibility to its apparent low corporate permeation. Brazil’s involvement in the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) and in challenging Intellectual Property Rights over antiretroviral drugs at the WTO may also explain this apparent low level of permeation. During negotiations for the FCTC, Brazil set a strong example, as its National Tobacco Control Programme implemented many innovations: Brazil was the second country (after Canada) to adopt graphic warnings on cigarette packages, the first to create a body to regulate tobacco contents and emissions, and the first to ban the use of “light” and “mild” to describe tobacco products (Lee, Chagas, & Novotny, 2010). Of relevance to this discussion is the fact that Brazil is one of the biggest producers and exporters of tobacco. In the words of Brazil’s then coordinator of the National Tobacco Control Programme, Vera Luiza da Costa e Silva,

“To be a big producer, a big exporter with a strong and influential industry, and a big consumer market for tobacco products, with pressures in the domestic market generated by allies of a powerful industry, Brazil actively supported all the WHO resolutions that led to the creation of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Body. “(Lee et al., 2010).

Brazil opposed large US-backed pharmaceutical companies who brought a WTO panel against Brazil for infringement of Intellectual Property Rights on antiretroviral drugs (ARVs). In the early 90’s Brazil provided universal coverage of antiretroviral drugs to HIV patients at zero cost. The affordability of this strategy hinged largely on domestic production of the drugs in a mix of state pharmaceutical enterprises and private generic manufacturers. Brazil purchased the remaining drugs on the international market, where the government sought to negotiate the best possible prices with international pharmaceutical companies (Galvão, 2002). This included the threat of issuing compulsory licences for ARV. In 2001, the WTO accepted a request for a panel by the US, who challenged Brazil’s patent laws that permit the compulsory license of patents under special conditions. Brazil fought the challenge and, in June 2001, the US withdrew its complaint before the WTO (Galvão, 2005) (Okie, 2006).

Fourth quartile, high permeation index

Among the first group, Luxembourg is particularly interesting because it has a very wide range of ranks, going from 31 to 147 in 2010 and 11 to 148 in 2015. In both years, the lowest ranks are obtained with the formulation that attributes the highest weights to factors that capture traditional quid pro quo corruption, the Public Private Sector Governance Factor. The highest ranks were obtained with formulations that weighted all indicators equally. The former is unlikely to singlehandedly capture the type of corporate permeation that put the country in the international spotlight for its role in facilitating large scale tax evasion. The so called “sweetheart deals” it secured with the world’s largest corporations were not overtly illegal. For example, in 2003 Amazon secured a confidential deal from the Luxembourg tax authorities. In 2014 that deal became the subject of a formal investigation by the European Commission on whether it constituted state aid (European Commission - Press Release, 2014). On the nature of the relationship between the company, the Luxembourg government and the then Prime Minister, Jean Claude Junker, Amazon’s former head of tax said

“The Luxembourg government presents itself as business partner, and I think it’s an accurate description: it helps to solve problems.” (…) [Jean Claude Junker and top civil servants’ message was:] “If you encounter problems which you don’t seem to be able to resolve, please come back and tell me. I’ll try to help” (Bowers & Watt, 2014).

In sum, formulations that relied more heavily on indicators of traditional illegal corruption seemed to fail to capture undue but borderline legal corruption. On the other hand, formulations that treated a wider range of variables on equal footing seem to better lend a quantitative explanation to the qualitative evidence of corporate permeation. This interpretation of ranges in light of the components of their underlying formulations can be used to analyse the wide score ranges in, for example, Ireland where similar tax deals have been documented.

Limitations of the CPI

The CPI has a number of limitations. First, we were unable to find comparable indicators for each of the “Enablers” of Corporate Power which means that some “Vehicles” of Corporate Power are better represented and characterized than others in the CPI. Second, the reliance on opinion surveys such as the EOS introduces a number of biases. Third, the time span of only six consecutive years may not be entirely informative.

We were unable to find comparable indicators for all the Enablers of permeation of the political environment. Quantitative measures of undue influence such as “lobbying, revolving-doors, and donations to political parties, candidates and campaigns” and “Direct participation in governmental agencies, committees and policy formulation” are particularly, if not impossible to find, especially in formats that render these measures comparable across countries. Data on financial contributions to parties, candidates, and election campaigns are not always systematically collected at the country level. Some exceptions should be noted such as the case of the Centre for Responsible Politics Lobbying Database in the US, who collects data on lobbying resources by company, lobbying firm or individual lobbyist. It also tracks total spending by a particular industry; the interests that lobbied a particular government agency and lobbying on a general issue or specific piece of legislation (Centre for Responsible Politics - Open Secrets, 2019). This initiative illustrates that it is possible to systematically track money and human resources invested in lobbying, and, pending more countries requiring such reporting, wider geographic data sources could make the CPI more accurate.

As it stands, where information exists, accuracy in reporting may vary from industry to industry and from institution to institution. Further, comparability among the few countries that do collect and report financial contributions is impractical at best. Lobbying, almost by definition,2 is a difficult activity to observe and quantify. Nonetheless, a wealth of public health research has drawn links between lobbying efforts and health research and health policy outcomes (Best, 2012, CEO, 2015, Costa et al., 2014; Ozierański, McKee, & King, 2012; Reardon, 2014).

Industries deploy diverse lobbing techniques, from open participation in consultative processes to direct communications with decision-makers to organizing sometimes intentionally misleading grassroots campaigns. Further, a notable portion of influencing efforts occur outside of any formal participatory or consultative channels, drawing on informal relationships and a variety of social interactions. Again, many of these communications and interactions are “by design” kept off the record.

One attempt by Transparency International to quantify undue influence in the EU found that the vast majority of countries have no comprehensive regulation of lobbying. Few countries have any requirements on the public sector to record information about their contacts with lobbyists and lobbying interest groups. Documented information is frequently too narrow or sporadic, and is rarely, if ever proactively released to the public. Where they exist, lobby registers are not coupled with meaningful oversight mechanisms. Although the majority of EU states have some revolving door regulations requiring a ‘cooling-off’ period before former public officials can lobby former colleagues, no state has effective monitoring and enforcement of these provisions (Mulcahy, 2015). Moreover, lawyers have been particularly reluctant to identify themselves as lobbyists and have argued that transparency requirements would violate lawyer-client privilege. Of the approximately 7,000 organisations registered in the EU’s voluntary Transparency Register, only 88 are law firms.

Most countries regulate participation in public consultations, but implementation is usually inconsistent across governments, and in no states have comprehensive requirements to provide detailed explanations regarding decision-making processes. A potentially interesting proxy for the “capacity” for undue influence is the prevalence of public-private partnerships. Outsourcing of public services, secondments into the public sector, and the use of advisory bodies all carry the risk of lobbying from the “inside,” with private actors having access to potentially privileged information and performing dual private-public functions (Holden, 2009, Mulcahy, 2015). The World Bank keeps a database of public-private partnerships in 139 low and middle-income countries. Whilst this is very good coverage by any measure, it leaves out a substantial part of our sample i.e. developed countries. We will, however, incorporate this measure into future calculations of the CPI when the World Bank expands its country coverage.

International trade enables corporate permeation of the political environment. Fortunately, quantitative and comparable indicators for trade are more readily available than for other enablers. This is not to say that there are no limitations to the use of these indicators. Trade indicators may mean different things in terms of corporate permeation in rich developed countries than they do in poor countries as a result of the power differential in the negotiation and implementation of multilateral and bilateral trade agreements. In other words, power imbalances may mean different things in developed and developing countries. For example, countries with small populations and economies might have to grant major concessions, increasingly beyond the stipulations of the World Trade Organisation agreements, to secure even modest improvements in market access. The differential is exacerbated by the common ground fostered by corporations and national bureaucratic political elites who will advocate on their behalf. For example, during the US negotiations for the Trans Pacific Partnership agreement, private industry and trade groups represented 85% of the committee members, vastly outweighing the representation of all other sectors such as civil society. At the supranational level, the weighting of IMF and World Bank votes by financial contribution propagates power imbalances in trade policy emanating from these institutions. Kentikelenis and colleagues argue that skilled social actors can introduce and legitimate new norms without recourse to formal processes of change. They demonstrate this by documenting how the U.S. and its allies engineered the rise of ‘structural adjustment’ at the International Monetary Fund in the 1980s. This entailed reorienting the organization towards intrusive, market-oriented policy reforms, even though its mandate formally precluded this approach (Kentikelenis, 2017). In sum, whereas the CPI encompasses objective measures of the vibrancy of trade in the different countries such as Foreign Direct Investment or the value of Trade Tariffs, they many translate different realities of corporate permeation depending on the negotiating power of the country in question in international trade negotiations or in the institutions that host these negotiations.

Indicators of “Enablers” of Corporate Permeation of “Preference Shaping” are equally hard to collect systematically in a comparable format. For example, like with public-private partnerships, it can be difficult to measure the influence of corporate interests on think-tanks and other institutions that help shape public discourse around corporate power. One survey by the Bertelsmann Stiftung on the Sustainable Development Indicators, examines this question. They ask their national informants “To what extent are economic interest associations capable of formulating relevant policies? In order to formulate such policies, interest groups will draw on capabilities such as their own academic personnel, associated institutes and think tanks, or they undertake cooperative efforts with academic bodies”, but only in developed countries. Future formulations of the Bertelsmann Stiftung Transformation Index, which focuses on developing countries, may include questions that capture the same concept and will be included in the next formulations of the CPI.

In sum, in the absence of objective measures of corporate undue influence, we relied on measures of perceived undue influence as captured by a variety of surveys. In the case of the Executive Opinion Survey, the respondents are business executives from small- and medium-sized enterprises and large companies representing the main sectors of the economy (agriculture, manufacturing industry, non-manufacturing industry, and services). This brings us to the second set of limitations of the CPI: challenges presented by these measures.

The business community may be more prone to underreporting or failing to report illicit behaviour, such as “informal lunches” with government officials, which despite their dubious connotations, may be entirely normalised and internalised within the community. There is also a risk that the reporting of illicit behaviour is inconsistent across countries. It is plausible that the business community in low and middle-income countries is composed of expatriates from high income countries. We cannot discard the possibility that business people have some inherent bias or double standards and report differently on the same phenomenon depending on whether they are in, say, countries of the G8 or in less advanced economies. In other words, practices that would not be reported as corrupt in G8 or OECD countries, e.g. revolving doors or business lunches, could potentially be reported as such in the rest of the world. In fact, we see a similar phenomenon occurring when it comes to the enforcement of anti-bribery laws. A significant number of high income countries who perform well on bribery control domestically, have a poor record of enforcing international antibribery laws abroad (Transparency International, 2016). If we assume that business people from OECD countries, for example, are overrepresented in business communities in both countries of origin and in less advanced economies, there is potential for this reporting bias to artificially polarize countries based on valid or even unsubstantiated perceptions of corruption. Flawed as it may be, however, the EOS is still by far the most comprehensive survey of attitudes and behaviours in the international business community.

The third limitation results from the modest time coverage of only six years, from 2010 to 2015, a compromise between data availability for the largest possible number of countries and length of the “observation period.” The fourth limitation regards the actual timing of the observations. Yearly differences in CPI values over just six years may not reflect long-term policy phenomena such as changes in health policy. A six year period still allows for cross-sectional analysis. The timing of the observations may pose a problem because the period coincides with either the economic crisis or its aftermath, which had diverse global affects.

Both limitations can be addressed by continuing to calculate the CPI in subsequent years.

Conclusion

The CPI is a novel tool that captures country level dimensions of the interaction between corporations and the wider society that are neglected by popular measures of quid pro quo corruption, traditionally employed by the World Bank or by Transparency International, with a focus on the public sector.

Whilst High Income Countries are overrepresented among the lowest scores, there is no clear regional pattern, with scores showing as much intra-regional as interregional variability.

Even though the CPI adds value to the study of the interface between corporate and public governance, country rankings must be examined with caution. The CPI does not accurately measure aspects of illicit corporate behaviour that became licit through processes of “privatization of the public policy”, including, for example amounts spent on lobbying at the country level or the frequency of revolving doors between the public and the private sector. This highlights the need for devising and strengthening legislation around mandatory reporting of lobbying activities and provisions of cooling off periods between employment in the public and the private sector, to name a few. Similarly, CPI gaps highlight the urgent need for robust monitoring and data collection systems for existing legal provisions.

In the future, the CPI may be used to explain variations in alcohol consumption and provide alternative explanations to the arguments that differences in alcohol consumption across countries are attributable to culture. Similarly, it can also be used to explain variations in obesogenic diets and the proliferation of gambling outlets. The CPI can also be used to explain variations in the formulation and implementation of public health policy and shed light on the associations between corporate permeation and the quality of public policy and the ability of health policy to mitigate against pressures from commercial interests to boost the consumption of unhealthful products. The CPI can also shed light on the role of corporate permeation in polarizing inequalities in the strictness and comprehensiveness of health policies among countries and in the prevalence of risk factors both between and within countries. Lastly, the CPI can be used as a monitoring tool for advocates and public health practitioners to track the relative progress of their countries in tackling the commercial determinants of health.

Acknowledgement

Joana Madureira Lima is the recipient of a Doctoral Scholarship from the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology. This paper was developed while she was a recipient of a Fulbright Scholarship for Research in Public Health.

Footnotes

Tables 5.1 to 5.6 show the rotated factor loadings for individual CPI indicators on the first through fourth imputed dataset, and in the two datasets resulting from conditional mean imputation using two normalisation methods

Lobbying is any direct or indirect communication with public officials, political decision-makers or representatives for the purposes of influencing public decision-making, and carried out by or on behalf of any organised group”

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100361.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

.

References

- Alkire, S. et al. (2012). An extensive analysis of gross national happiness index. Thimphu. Available at: http://www.grossnationalhappiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/An Extensive Analysis of GNH Index.pdf.

- Allison P.D. Sage Publications; London: 2002. Missing data. [Google Scholar]

- Alvy L.M., Calvert S.L. Food marketing on popular children’s web sites: A content analysis. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2008;108(4):710–713. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkin N. VW scandal exposes cozy ties between industry and Berlin. Reuters; 2015. Available at: 〈 http://www.reuters.com/article/us-volkswagen-emissions-germany-politics-idUSKCN0RQ0BU20150926〉. [Google Scholar]

- Best R.K. Disease politics and medical research funding: Three ways advocacy shapes policy. American Sociological Review. 2012;77(5):780–803. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers S., Watt N. The Guardian; 2014. Luxembourg tax files: Juncker “solved problems” for Amazon move.〈https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/dec/10/juncker-amazon-luxembourg-eased-tax-expert-comfort〉 Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Brownell K.D., Warner K.E. The perils of ignoring history: Big tobacco played dirty and millions died. How similar is big food. Milbank Quarterly. 2009;87(1):259–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00555.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Responsible Politics - Open Secrets (2019). Open Secrets Database, Lobbying Database. Available at: 〈https://www.opensecrets.org/lobby/〉 Accessed 05.01.19.

- CEO (2015). Policy prescriptions: The firepower of the European Pharmaceutical Lobby and Implications for Public Health. Brussels. Available at: 〈http://corporateeurope.org/power-lobbies/2015/09/policy-prescriptions-firepower-eu-pharmaceutical-lobby-and-implications-public〉.

- Costa H. Quantifying the influence of the tobacco industry on EU governance: Automated content analysis of the EU Tobacco Products Directive. Tobacco control. 2014;23(6):473–478. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donders A.R.T. Review: A gentle introduction to imputation of missing values. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2006;59(10):1087–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Commission - Press Release (2014). State aid: Commission investigates transfer pricing arrangements on corporate taxation of Amazon in Luxembourg, European Commission. Available at: 〈http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-14-1105_en.htm〉 (Accessed 23 August 2017).

- Farnsworth K., Holden C. The business-social policy nexus: Corporate power and corporate inputs into social policy. Journal of Social Policy. 2006;35(3):473–494. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (2017). Introducing the German Mittelstand. Available at: 〈http://www.make-it-in-germany.com/en/for-qualified-professionals/working/mittelstand〉 (Accessed 22 August 2017).

- Fuchs D. Commanding heights? The strength and fragility of business power in global politics. Millennium - Journal of International Studies. 2005;33(3):771–801. [Google Scholar]

- Galvão J. Access to antiretroviral drugs in Brazil. Lancet. 2002;360(9348):1862–1865. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11775-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvão J. Brazil and access to HIV/AIDS drugs: A question of human rights and public health. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(7):1110–1116. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.044313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambino L. The Guardian; 2018. NRA contributions: How much money is spent on lawmakers?〈https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2018/feb/16/florida-school-shooting-focus-shifts-to-nra-gun-lobby-cash-to-lawmakers〉 Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield K., Winkler A. The Atlantic Magazine; 2015. The U.S. supreme court’s cultivation of corporate personhood.〈https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2015/06/raisins-hotels-corporate-personhood-supreme-court/396773/〉 Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Holden C. Exporting public–private partnerships in healthcare: Export strategy and policy transfer. Policy Studies. 2009;30(3):313–332. [Google Scholar]

- Holden C., Lee K. Corporate power and social policy: The political economy of the transnational tobacco companies. Global social policy. 2009;9(3):1–22. doi: 10.1177/1468018109343638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotten R. BBC News; 2015. Volkswagen: The scandal explained.〈http://www.bbc.com/news/business-34324772〉 Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen P.D. Pharmaceuticals, political money, and public policy: A theoretical and empirical agenda. Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics. 2013;41(3):561–570. doi: 10.1111/jlme.12065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauffmann, D. (2004). ‘2.1. Corruption, Governance and Security: Challenges for the Rich Countries and the World’, in Global Competitiveness Report. 2004/2005. Washington DC: World Bank Institute, pp. 83–102. Available at: 〈http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTWBIGOVANTCOR/Resources/Kaufmann_GCR_101904_B.pdf〉.

- Kauffmann D., Vicente P. Legal corruption. Economics Politics. 2011;23(2):195–219. [Google Scholar]

- Kearns C.E., Schmidt L.A., Glantz S.A. Sugar industry and coronary heart disease research. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2016:9. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kentikelenis, A. (2017). ‘How Neoliberalism Went Global: The Rise of Structural Adjustment in the International Monetary Fund’, in Department of Sociology (ed.) How Neoliberalism Went Global: The Rise of Structural Adjustment in the International Monetary Fund. Oxford. Available at: 〈https://www.sociology.ox.ac.uk/events/how-neoliberalism-went-global-the-rise-of-structural-adjustment-in-the-international-monetary-fund.html?Cckid=194catid=50〉.

- Langbein L., Lotwis M. The political efficacy of lobbying and money: Gun control in the U. S. house, 1986. Legislative Studies Quarterly. 1990;15(3):413–440. [Google Scholar]

- Lee K., Chagas L.C., Novotny T.E. Brazil and the framework convention on tobacco control: Global health diplomacy as soft power. PLoS Medicine. 2010;7(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon J.R. Assessment of the Bhutan anti-corruption commission 2015. 2015. Available at: 〈 https://www.transparency.org/whatwedo/publication/assessment_of_the_bhutan_anti_corruption_commission_2015〉. [Google Scholar]

- Lukes S. Power a radical view. Second. Palgrave McMillan; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Madureira Lima J., Galea S. Corporate practices and health: A framework and mechanisms. Globalization Health. 2018;14(1) doi: 10.1186/s12992-018-0336-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mccambridge J., Hawkins B., Holden C. Vested Interests in Addiction Research and Policy: The challenge corporate lobbying poses to reducing society’s alcohol problems: Insights from UK evidence on minimum unit pricing. Addiction. 2014;109(2):199–205. doi: 10.1111/add.12380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mialon M., Swinburn B., Sacks G. A proposed approach to systematically identify and monitor the corporate political activity of the food industry with respect to public health using publicly available information. Obesity Reviews. 2015;16(7):519–530. doi: 10.1111/obr.12289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milne R. The Financial Times; 2016. Olafur Hauksson, the man who jailed Iceland’s bankers.〈https://www.ft.com/content/dcdb43d4-bd52-11e6-8b45-b8b81dd5d080〉 Available at. [Google Scholar]

- Mindell J.S. All in this together: The corporate capture of public health. British Medical Journal. 2012;345:e8082. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e8082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulcahy, S. (2015). Lobbying in Europe. Available at: 〈https://www.transparency.org/whatwedo/publication/lobbying_in_europe〉.

- Nardo, M. et al. (2005). Tools for composite indicators building. 〈 10.1038/nrm1524〉. [DOI]

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) Handbook on Constructing Composite Indicators: Methodology and User Guide. 2008. (Methodology). [Google Scholar]

- Okie S. Fighting HIV — Lessons from Brazil. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;354(19):1977–1981. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozierański P., McKee M., King L. Pharmaceutical lobbying under postcommunism: Universal or country-specific methods of securing state drug reimbursement in Poland? Health Economics, Policy and Law. 2012;7(2):175–195. doi: 10.1017/S1744133111000168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reardon S. Lobbying sways NIH grants. Nature. 2014;515(7525) doi: 10.1038/515019a. 〈https://www.nature.com/news/lobbying-sways-nih-grants-1.16280〉 Available at. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer J.L., Graham J.W. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(2):147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serôdio P.M., McKee M., Stuckler D. Coca-Cola - A model of transparency in research partnerships? A network analysis of Coca-Cola’s research funding (2008–2016) Public Health Nutrition. 2018;21(9):1594–1607. doi: 10.1017/S136898001700307X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddique H. The Guardian; 2017. McDonald’s pulls ad that ‘exploited child bereavement. Available at: 〈 https://www.theguardian.com/business/2017/may/16/mcdonalds-apologises-over-ad-exploiting-child-bereavement〉. (Accessed: 20 May 2017) [Google Scholar]

- Siegel K.R. Association of higher consumption of foods derived from subsidized commodities with adverse cardiometabolic risk among US Adults. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2016;312(2):189–190. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver-Greenberg J., Craig S. The New York Times; 2014. Fined Billions, JPMorgan Chase Will Give Dimon a Raise.〈https://dealbook.nytimes.com/2014/01/23/fined-billions-bank-approves-raise-for-chief/?hp&_r=0〉 Available at. [Google Scholar]

- Simon M. The best public relations money can buy: A guide to food industry front group. Centre for Food Safety; Washington DC, USA: 2013. Available at: 〈 http://www.centerforfoodsafety.org/files/front_groups_final_84531.pdf〉 (Accessed 17 March 2016) [Google Scholar]

- Spies M. The New Yorker; 2018. The N.R.A. lobbyist behind Florida’s pro-gun policies.〈https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/03/05/the-nra-lobbyist-behind-floridas-pro-gun-policies〉 Available at. [Google Scholar]

- Stata (no date) Multiple Imputation: Impute using predictive mean matching, Stata Manual. Available at: 〈https://www.stata.com/manuals13/mimiimputepmm.pdf〉.

- The New York Times . The New York Times; 2010. Iceland voters reject repayment plan.〈https://dealbook.nytimes.com/2010/03/07/iceland-voters-reject-repayment-plan/?_r=0〉 Available at. [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank (2013). Bhutan partnership: country program snapshot. 81703. Available at: 〈http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/649331468013173836/World-Bank-Group-Bhutan-partnership-country-program-snapshot〉.

- Transparency International (2016). Bribe Payers Index, Bribe Payers Index. Available at: 〈https://www.transparency.org/research/bpi/〉 (Accessed 18 August 2016).

- White S.K. Corporations, Public Health, and the Historical Landscape that Defines Our Challenge. In: Wiist W.H., editor. The Bottom Lime or Public Health Tactics that Corporations Use to Influence Health and Health Policy, and What We Can Do to Counter Them. 1st edn. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2010. pp. 73–96. [Google Scholar]

- Wu X. Corporate governance and corruption. Governance: An International Journal of Policy, Administration, and Institutions. 2005;18(2):151–170. [Google Scholar]

- Yong A.G., Pearce S. A beginner’ s guide to factor analysis: Focusing on exploratory factor analysis. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology. 2013;9(2):79–94. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material