Abstract

This article undertakes a close reading of the parliamentary debates associated with the topic of embryo cryopreservation in Aotearoa New Zealand. From our critical readings, we argue that there is a lack of transparency over the ethical reasons for enforcing a maximum storage limit. We demonstrate that arguments for the retention of this limit are associated (in New Zealand) with arguments based upon ‘build-up avoidance’ and ‘conflict avoidance’ as social goods based on Pākehā [New Zealander of European descent] cultural world views rather than identifiable universal ethical principles. We illustrate that the avoidance of embryo accumulation and related conflict was only achieved by the denial of indigenous spiritual and cultural concerns, while also shifting the ethical burdens of disposition on to clinic staff and those members of the public who protested against enforced cryopreserved embryo disposal. The Pākehā cultural concept of ‘tidy housekeeping’ emerges as a presumed ethical and social good in the New Zealand situation. This is despite abundant literature documenting the suffering created through forced decision-making upon disposition.

Keywords: bioethics, embryos, cryopreservation, indigenous, Aotearoa/New Zealand

Highlights

-

•

The ethical justification for finite storage limits of cryopreserved embryos varies cross-culturally.

-

•

Indigenous bioethical views were excluded from New Zealand parliamentary debates on the storage limits for cryopreserved embryos.

-

•

In New Zealand, mandated storage limits for cryopreserved embryos have been treated as a ‘tidying up’ legislative practice, in which removing ‘matter out of place’ had provided its own ethical reward.

-

•

As a result, an unacknowledged ethical burden has been placed upon indigenous citizens, individual clients and scientific workers.

Introduction

At the present time, the maximum permitted duration for the cryopreservation of embryos varies remarkably between countries. It ranges from no limit in the USA, China and Spain to as little as 1 year in Norway, 2 years in Denmark and Finland, and up to 10 years in the UK, most of Australia and New Zealand (IFFS, 2016). These diverse regulatory regimes reflect different local economies and reproductive governances, and the well-known difficulties in deciding upon a universal standard or value system attached to such localized lives and their purpose (Nie and Fitzgerald, 2016). Such a disconnect has consequences; in Simpson's (2013: S87) words, ‘the tension that arises between local worlds of meaning, morality, and kinship on the one hand and the powerfully naturalizing discourses of law, regulation, and bioethics in which they are encompassed on the other’. In this article, we draw on a close reading of such tensions manifesting in the New Zealand parliamentary debates surrounding enforced embryo cryopreservation limits to reveal the stratified reproduction (Colen, 1986, Ginsburg and Rapp, 1991) created through these debates. This occurred through the predominantly Pākehā [New Zealander of European Descent] parliamentarians' extraordinary neglect and oversight when considering the views of Māori [indigenous people of New Zealand] parliamentarians on the cultural significance of these enforced maximum storage times for the wider minority Māori population. Rights over reproduction are key elements of social citizenship for indigenous communities, as reproduction in its familial, cultural and societal regenerative aspects are frequently intertwined (Alcoff, 2008, Ginsburg and Rapp, 1991, Stone, 2018). The denial of one aspect of reproductive rights, such as the ability to be offered embryo cryopreservation services in a culturally sensitive manner, when repeatedly enacted on individual indigenous families can impact in the longer term on the vitality and recognition of the wider indigenous cultural identity.

In our New Zealand example, the representational biases against Māori views on embryo cryopreservation in the parliamentary debates have been particularly unjust. This is because in Aotearoa New Zealand, the background framework of the Treaty of Waitangi creates a moral imperative to attend to the issues of partnership, participation and protection in all aspects of national life, including healthcare provision by both treaty partners, i.e. Pākehā and Māori (MoH, 2018). The universalizing discourses of ethical regulation of cryopreservation and ‘normal’ biomedical practices of embryo disposal were never meant to subsume Māori interests in these topics. This is demonstrated, for example, in the guiding principles of the Advisory Committee on Assisted Reproductive Technology (ACART), the national bioethics committee that oversees new technologies, which states: ‘the different ethical, spiritual, and cultural perspectives in society should be considered and treated with respect’ (https://acart.health.govt.nz/about-us). In practice, however, this has not been the case, as Glover et al. (2008: 95–98) have described in detail. Instead, we see a national reproductive healthcare environment that is marked by the low rate of uptake of in-vitro fertilization (IVF) services within Māoridom (ibid, 2008; Reynolds, 2012); the apparent higher rate of infertility across the wider New Zealand population than global estimates for countries of similar wealth (Righarts et al., 2015); and the accounts of expressed suffering of Māori families struggling with interrupted fertility (Pihama, 2012). When considered together with the findings of this paper, it becomes possible to appreciate the strength of the continued structural press against Māori capacities to reproduce at individual, societal and cultural levels.

Background studies of social suffering and embryo cryopreservation

To understand New Zealand's decision to create maximum permissible storage limits for cryopreserved embryos is a complex task. The decision ran contrary to existing empirical studies (which we review briefly below) that were available for consultation by parliamentary researchers during the legislative process. These studies (had they been considered seriously) would have revealed evidence of the associated suffering surrounding the disposal decision-making that such limits invite. Williams et al. (2008), for example, argued that embryos create moral dilemmas in three aspects of their ‘social’ lives: as waste, as potential kin and as research objects. Cryopreservation and the requirement to eventually dispose of the embryos adds conflict to all three of these dimensions in the following ways.

With regard to their identity as waste, the manner of disposal of the embryo can be morally contested (Jonlin, 2015), as can the timing of disposal. For example, studies by Nachtigall et al. in the USA (where open-ended storage time is permitted) demonstrate how such opinions may vary over time (Nachtigall et al., 2005, Nachtigall et al., 2009). The key contribution to the difficulty of the disposition decision, which they identified, was related to the variety of ways in which participants viewed the moral status of embryos. These approaches included “biological tissue, living entities, ‘virtual’ children, genetic or psychological ‘insurance policies’, and symbolic reminders of their past infertility” (ibid, 2005: 431). Subsequently, the authors developed a steplike model for the process of decision-making in these circumstances, and note that such decision-making was ‘often marked by ambivalence, discomfort, and uncertainty’ (Nachtigall et al., 2009: 2094). In de Lacey's (2005) South Australian study of nine women and 12 couples who changed their mind about donating embryos (against a background maximum storage limit of 10 years) in favour of discarding them, she argues that retaining the embryos indefinitely in a cryopreserved state ‘would have been preferable’ than having to make a disposition decision. de Lacey concludes that people decided on their method of disposition in order ‘to avoid the ethical dilemma that they did not wish to endure’ in which embryo donation was a similar emotional landscape to ‘child relinquishment’ (2005: 1661). Another Australian study by Karpin et al. (2013: 5) notes that maximum storage limits created suffering by adding time pressure to complex family decision-making. The mandated limit removed autonomy, escalated the costs of treatments, and created distinctly gendered dilemmas of unanticipated and disconnected embodied experience of self and embryos (ibid: 6).

Similarly, a Chinese study of 363 couples by Jin et al. (2013), against a backdrop of no maximum legal limit for embryo storage, argues that clients' eventual disposition decisions were based on avoiding certain key ethical complexities. Lyerly et al. (2010) explored disposition decision-making in their cross-sectional survey of 1020 clients drawn from nine US IVF centres. The study concluded that clients were quite unlikely to be offered the method of disposition that they would have preferred. Particular concerns were the lack of provision of a suitable ritual ceremony for disposition, and the lack of the option of implanting the embryos in conditions unlikely to result in pregnancy. As the authors noted in an earlier associated study, ‘embryo cryopreservation may have untoward consequences, among which is the burden of facing what may be a morally difficult decision in the future’ (Lyerly et al., 2006: 1629). A particularly relevant example in Aotearoa New Zealand is where Māori concerns over disposition of frozen embryos are subsumed within the dominant social majority views on appropriate disposition. In this context, the appropriate location for such disposal is a debated issue. When Māori consider the disposition of embryos or fetuses, they are affording these living status whilst they are inside the womb (i.e. they are viewed as living entities); they are spoken to, sung to and addressed in the same way as a newly born child. As the embryo/fetus is recognized as a living entity, it has wairua, mauri, oho and hau (a collective of elements that are afforded to living entities, such as spirit, soul, living vitality and essence). Upon death, although the human body is interred, the essences synonymous with the living, mentioned above, take leave from the physical corpse to the ‘spiritual world’. The essence is still, however, spiritually attached with the physical body, be it alive or dead; therefore, there are cultural understandings that apply. Some Māori, for example, have been known to argue against the burial of body parts and body waste from living humans in urupā [cemeteries or burial sites] because designated urupā have been primarily designated for the dead, not for the living or body parts taken from living people. In the case of an amputee who may have his or her leg buried in a cemetary, the house joke ‘having one foot in the grave’ would be convivially expressed; however, underlying such a statement was caution that depositing part of a living person there may also infer that the remaining living parts of the body, that is, the person, might then follow. In the past 20 years, however, there has been some shift regarding this way of thinking, and Māori are renegotiating the correctness of such a practice of mixing aspects of the dead and the living. With regard to embryos however, the viewpoint still holds that it is a living entity.

A completely different social trajectory for embryos involves their social lives as potential kin. The presumed stability in family make up by IVF users in their initial thoughts on embryo disposition1 is an element of the process that can prove troubling at a later date, as family dissolution can still occur during what may be a lengthy cryopreservation period. The resulting legal battles over embryo custody and uses have mainly been published from the USA (Kindregan and McBrien, 2013). For example, in the previously mentioned US study, Lyerly et al. (2011) note that 39% of 1244 survey respondents reported ‘high decisional conflict’ over the topic of embryo disposition. In one of the serially published sets of results from a large Belgian study of embryo disposition (Provoost et al., 2011), non-responders to clinic requests for an embryo disposition decision were contacted to explain their avoidance. A full 12% of these non-responders cited the inability to come to agreement within the client couple as the reason for not responding. For Māori, in addition to these intrafamilial sites of discord, there are also larger relational groups to consider such as iwi [tribe] and hapū [subtribe] viewpoints. The study by Glover and Rousseau (2007), which explored the complexities of understanding reproductive technologies and their meaning for kinship within one particular iwi, suggests additional rather than fewer layers of controversy surrounding cryopreservation than the current Eurocentric-focused literature suggests.

Embryos may also serve in a positive way as a symbol of the relationship between the couple, as demonstrated in another Belgian publication involving a questionnaire of 412 participants (Provoost et al., 2012). The deeply personalized meanings attached to the embryo made it difficult to consider donating the embryo to another couple with problems of fertility; this was also noted in the previously mentioned Australian study by de Lacey (2005). This inwardly focused direction of thinking (i.e. back to the effects of disposition on the parents) contrasts with the findings of the study by Roberts (2011) of Ecuadorian couple's decision-making over embryo disposition. This ethnographic study reveals Ecuadorian couples' decision-making as being based on an outwardly oriented sense of kinship that focused on the kinship systems of the future offspring. Given the great significance of whakapapa [genealogies] within Māoridom, one could expect similar differences in decision-making over cryopreservation between Pākehā and Māori populations. Roberts' study contrasts such an orientation to US study sites where embryonic futures are understood within two dominant trajectories – as potential persons or as potential contributions to science (as research objects) – presenting quite different moral quandaries if not taken up. Paul et al. (2010: 258) note the minority of US families who donate embryos in order to honour kinship connections, and emphasize the painfully complex nature of making such a decision, noting its ‘both short and long term complex psycho-social dilemmas’ (Paul et al., 2010: 258). The Brazilian study by Melamed et al. (2009) cites ‘child abandonment’ as one of the key reasons why women refuse to donate embryos, along with strong consideration of the human quality of the embryo. Kato and Sleeboom-Faulkner’s (2011) Japanese study also highlights the nature of embryos as potential siblings to existing family; again, an emphasis on their value as relatedness rather than their isolated, individualized value. In Afshar and Bagheri's (2013) discussion of embryo donation in Iran, they argue that the problem of kinship resides in differing views on the nature of the primacy of the relations between offspring – biological and social parents – with religious arguments capable of supporting both interpretations, and the relevant legislation remaining silent on the issue.

Given that these IVF clients engaged directly with the idea of the embryo as future kin, the mandated destruction of embryos as an appropriate, one-approach-fits-all, ‘ethical response’ to their continued cryopreservation overlooks the social harm of the destruction of these culturally quite distinctively experienced kinship bonds. This is crucial to the New Zealand dilemmas, when the dominant social majority population of Pākehā parliamentarians ignored the different cultural values afforded to potential kin by Māori parliamentarians.

The manipulation of embryos as moral work objects by embryologists and other biological scientists associated with IVF laboratories is an area that has been even less systematically studied than the views of clients and, we argue, also subject to the experience of moral suffering. The spatialized metaphor of a moral landscape (Svendsen and Koch, 2008) has been used to describe the varied moral pathways which physicians and scientists traverse in order to declare an embryo to be ‘spare’ and thus, in some locales, available as a scientific work object. The terrain is ethically contested and is unequally located around the globe (IFFS, 2016), with New Zealand exhibiting permissive legislation for research although the authority for regulation of such research cannot be obtained from Parliament. Rosemann's (2011) study of the regulatory context for embryonic stem cell research in China compared with the UK argues that the ‘value’ of embryos is open to strategic construction in China with respect to the information supplied to ‘donors’ and the accrual of value to researchers. This instability in the moral nature of the embryo is also the case for the UK-based scientists working with embryos as research objects, as argued by Williams et al. (2008: 15). Depending on whether the embryo was being used during pre-implantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) or stem cell research, it shifted in its social meaning. The possible ascribed status of these embryos ranged from ‘affected spare PGD embryos’ or ‘waste in PGD’, to highly valued ‘disease in a dish’ in embryonic stem cell research procedures. Ethical concerns for such scientists when required to discard embryos have been noted in the UK (Ehrich et al., 2008) and New Zealand (Fitzgerald et al., 2013). In New Zealand, the difficulties arise not from research, but from the voluntary or mandated ending of cryopreservation which then places responsibilities for physical disposal on to the shoulders of the embryologists – a requirement of their duties but one that is frequently troubling.

In support of these comments and in a rare comparative study between the UK and Switzerland, Haimes et al. (2008) argued that ‘the embryo’ as a research object is a shifting and ambivalent concept created out of the confluence between situated discourses from the public, clinic and family. Our paper argues for a further discursive stream to be added to this confluence, namely the cultural concerns of indigenous communities.

The press towards mandated storage times as an ethically desirable aspect of regulation appears episodically in the literature. For example, writers from the UK have expressed concern over the temporal discontinuities of familial generations created through lengthy cryopreservation (Simpson, 2013). Certain regulatory authorities, such as the Reproductive Technology Council in Australia (Karpin et al. 2013: 3), have noted that indefinite storage has ‘questionable’ ethical outcomes. Stuhmcke (2014: 301), in a related study, notes the press towards maximum storage times in Australia as being a regulatory response to the otherwise ‘purposelessness’ of infinitely stored embryos. Together, these ideas create the momentum for the presumed ‘good’ in maximum permissible storage times. However, if we add to this consideration the UK findings by Goswami et al. (2015) that the clients in their study rarely understood the implications of deciding to freeze reproductive material, the wide variation in maximum storage times around the world, the small size of human embryos and the relative ease with which many thousands can be successfully stored in liquid nitrogen tanks, we ask why is it that, in 2004, the ethical imperative in a sparsely populated country like Aotearoa New Zealand was to introduce a maximum storage time for cryopreserved human embryos? The current literature suggests that all efforts at disposal create some degree of personal suffering, so our question is, why impose such a limit? Where is the public ‘good’ that legislators proposed that they were following?

Methods

To answer this question, we conducted a qualitative critical discourse analysis (Wetherell et al., 2001, Wodak and Chilton, 2007) of the relevant Hansard Debates within New Zealand as they pertained to the topic of embryo preservation, and the precursor UK debates which were influential in the crafting of the New Zealand legislation. New Zealand society has a strong internal referent to the UK due to its colonizing history, much more so than other anglophone settler societies (Phillips, 2015). Sections of the debates were chosen for their references to the arguments both for and against limiting storage. These transcripts and official briefing papers for the debates were obtained from the New Zealand Parliament webpage (https://www.parliament.nz/en/pb/hansard-debates), and read and verified for key themes by all authors. The texts were analysed in relation to language, tone and discourse to determine their particular discursive practices concerning the ethics of embryo cryopreservation and disposal. The technique used was based on our previous discourse analysis studies (Wardell et al., 2014), and involved detailed multiple readings of each text, taking note of keywords, type of language (e.g. emotive, legal, medical), focus and scope of content, tone, and the structuring and oppositional positioning of arguments within the text. As several indigenous Māori words and phrases were used during these debates and in this paper, their translation into English is followed in square brackets after the word. The resulting analysis is presented under sections that reflect the organizing time sequence of the prescribed checks and balances provided by the New Zealand legislative process. This process can be viewed at https://www.parliament.nz/en/visit-and-learn/how-parliament-works/how-laws-are-made/how-a-bill-becomes-law/. This layout thus reflects, in a meta sense, the repetitive rather than singular denial throughout this process of stated Māori concerns. The structured points embedded within the legislative process were designed specifically as further opportunities for parliamentarians to take additional advice and hear expert opinions, and thus more deeply inform the parliamentary debate on the substance of proposed legislation passing through the house. That such existing (multiple) structural ‘pauses’ in the passage of proposed legislation were used only as opportunities to speed up the passage of the legislation is quite telling of the force with which the Pākehā views were prioritized over indigenous concerns.

As this study utilized public information, ethical approval was not required.

Basis for Aotearoa New Zealand legislation

Given that New Zealand's legislative framework for regulating embryo storage [i.e. the Human Assisted Reproductive Technology (HART) Act 2004] drew heavily on the UK legislation [Human Fertilization and Embryology (HFE) Act 1990], which itself drew upon the findings from the Warnock Report (1984), it was important to begin by considering the UK parliamentary debates. This was to determine if the basis for mandatory storage, which authorized the New Zealand legislation, was borrowed from the earlier HFE Act. However, a search of Hansard UK (Health Committee Debate, 23 November 1984: 68; cc528–544) shows a very scanty discussion of cryopreservation of gametes and embryos in the Lower House. This occurred in the context of reservations expressed relating to the safety and long-term outcomes of children conceived from cryopreserved embryos. Sir Bernard Braine (ibid: c543) observes:

Nowhere does the [Warnock] report discuss what legal recourse the children would have if – God forbid – they found themselves faced with a tragic disability as a result of being frozen at the start of their lives.

All contributing members in the debate, both those in favour of IVF and those against it, drew on the metaphor of embryo experimentation to discuss the issue of cryopreservation. For some, it was the newness of the science that made it experimental, with Mr. Michael Meacher recalling the words of an original Warnock Committee Member, Mrs. Jean Walker: ‘Frozen embryos did not exist when we started the inquiry, but by the time we finished, the first baby had been born’ (Hansard UK 1984: c536–537).

The general sense is that UK Members of Parliament (MPs) were very cautious of the science underpinning cryopreservation, echoing the Warnock Report's assertion that IVF at that time was experimental, and thus a time limit seemed prudent. The final outcome of this debate (HFE Act 1990) was the establishment of a 5-year limit for the storage of embryos, with the Human Fertilization and Embryology Authority in practice remaining adamant that clinics ignoring this legal requirement would face the full force of the law, including clinic closures (Edwards and Beard, 1997). In 2008, the limit was increased to 10 years with some rare exceptions, which could allow a maximum of 55 years of storage (Jackson, 2016).

While continuing to engage in IVF since the 1980s, New Zealand took longer to regulate its practice than the UK. Consideration of the topic began with a Private Members Bill (Human Assisted Reproductive Technology Bill), first proposed by Dianne Yates in 1996. It was based on the UK legislation and, eventually, with additional debate and expert input, became the basis for the HART Act (2004). The law allowed for a cryopreservation storage period of 10 years, and treated punitively any storage period in excess of that as an ‘offence (carrying maximum penalty on summary conviction of $20000)’ (HART Act 2004). The public submissions and parliamentary debates around this bill have been studied extensively by Park et al. (2008) and McLauchlan and Park (2010), but contain no reference to storage limitations for cryopreserved embryos. It would appear that the need for a maximum storage provision was taken as a ‘given’.

In 2010, a legal opinion provided to the New Zealand Ministry of Health questioned the common understanding of the HART Act 2004. The suggestion was that it could have been read as any person with gametes or embryos stored prior to the Act, and which had been stored for more than 10 years, was breaking the law. This apparent anomaly led to the passage of the Human Assisted Reproductive Technology (Storage) Amendment Act 2010, the deliberations for which we discuss in a little more detail since they involve debate over the precise topic of interest – cryopreservation limits.

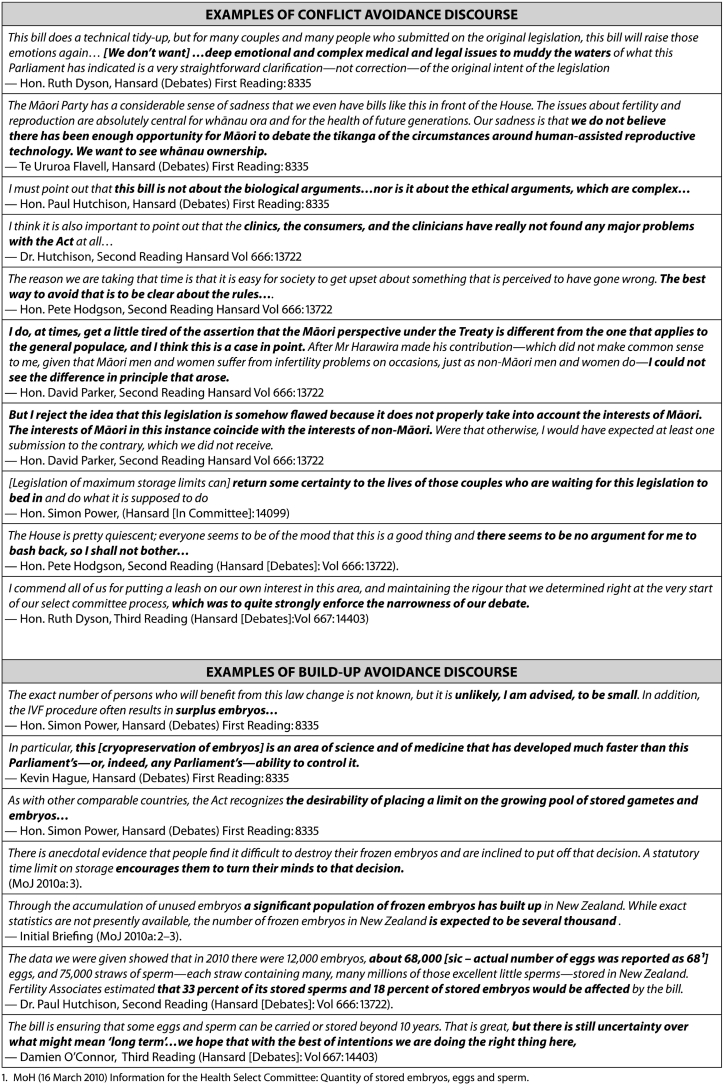

From this point onwards, two discourses (one major and one minor) emerged to frame the issues surrounding cryopreservation limits, and excerpts from these are set out in Fig. 1. They comprised a minor authorizing discourse surrounding the need for ‘build-up avoidance’ based on comments that reflected a sense of panic over the unknown number of embryos affected by the proposed time limit, anxiety over the large number of embryos (erroneously cited), and an amorphously conceived general ‘good’ in limiting the number of embryos. The second more strongly worded discourse of ‘conflict avoidance’ weaved through these anxious references to mounting numbers of frozen embryos, and reflected a beneficial quality in legislation that was clear to interpret, a sense that the legislation was neutral and thus able to include all local interests, and a determined refusal to consider any contrary views. Taken together, these discourses created an overarching discursive approach to ‘good’ legislative practice that we refer to as ‘tidy housekeeping’. Several parliamentarians used exactly this term (as the following results show) to describe their practice and to link it to an ethical duty to regulate the build-up of embryos.

Fig. 1.

Examples of the ‘conflict avoidance’ and ‘build-up avoidance’ discourses in the New Zealand parliamentary debates which reinforced each other to create the overall discursive Pākehā cultural response to cryopreserved embryos of ‘tidy housekeeping’.

In the Bill's first reading, storage was considered simply to be a technical procedure that was not difficult to undertake or regulate. Simon Power, Minister of Justice, set the overall tidy housekeeping tone of the discussion as follows: ‘As with other comparable countries, the Act recognises the desirability of placing a limit on the growing pool of stored gametes and embryos while at the same time acknowledging that in some cases there is often good reason to extend the storage beyond the set limit’ [Hansard NZ (Debates) 2009: 8335]. The continued framing of the activity as tidying was noticeable throughout the successive readings and debates. The Hon. Steve Chadwick referred specifically to the amendment as ‘a tidy-up of legislation’ [Hansard NZ (Debates) 2009: 8835]. Kevin Hague agreed noting, ‘The bill tidies that up nicely’ [Hansard NZ (Debates) 2009: 8835]. Iain Lees-Galloway also noted Parliament's task as ‘just to tidy up some aspects of the bill’ [Hansard NZ (Debates) 2010a: 13722]. Finally, the Hon. Damien O'Connor observed, ‘It tidies up some misunderstandings that have occurred’ [Hansard NZ (Debates) 2010d: 14458].

Only one discourse emerged to oppose this tone of ‘good’ housekeeping, and successive members of the Māori Party presented this in a series of addresses to the House. The first dissenting view came from Te Ururoa Flavell (MP), who argued: ‘…it should be up to the people from whom the in vitro gametes and embryos came from to decide how long they should be stored for and what they should be used for, including what happens in the event of their death’ [Hansard NZ (Debates) 2009: 8835]. Flavell raised specific points of interest for a variety of Māori on this issue, such as the concepts of survival, ownership and control. He drew on two resources to support his arguments: Te Puāwai Tapu (a long-established Māori organization dedicated to Māori sexual and reproductive health promotion, education and policy advice) and the paper by Glover and Rousseau (2007) exploring an empirical analysis of some Māori understandings of IVF. In citing this paper, Flavell argued that the legislation around storage must:

…facilit[ate] the rangatiratanga [authority, sovereignty] of whānau [family] over their whakapapa [genealogy] material... Such vital issues of survival should not be left to the realms of an ethics committee to decide. Te Puāwai Tapu also recommends that these elements of ownership and control should be apparent at every stage throughout the process. It suggests that tikanga [customary practices] must be applied at all stages, from the decision to enter into the process of fertility treatment to the completion and return of āhua kahukahu [spirit2 within the embryo], the unripened seed’ [Hansard NZ (Debates) 2009: 8835].

He emphasized that there had not been:

…enough opportunity for Māori to debate tikanga [customary practices] of the circumstances around human assisted reproductive technology. We want to see whānau [family] ownership. A collective sharing and responsibility is fundamental in the debate around whakapapa [genealogy]. We want to hear Māori voices in the literature and in the policy design [Hansard NZ (Debates) 2009: 8835].

Of particular relevance to our arguments about the social suffering caused by mandatory story limits, Te Ururoa Flavell (ibid) notes in a wider sense:

For many of us, when we consider the storage of human embryos and fertility clinics there is a sense of awkwardness and discomfort. That discomfort, that sense of something not being quite right, is the anxiety about the aspects of tikanga, of custom. We worry about the mana [authority] of the process, the wairua [spirit] of the gametes, and the authority of the whānau [family]. We are nervous that the tikanga [customary practices] of gifting and sharing of whakapapa [genealogy] brings with it certain expectations associated with the passing over of a life force.

Despite this expression of concern, the subsequent comments from MPs ignored Flavell's arguments at this first reading of the Bill.

Health Select Committee input

The Bill was then considered by the Select Committee, whose role in Parliament is to investigate and balance public opinion on the topic of the Bill with expert advice. A Departmental Report (Select Committee Advice: Departmental Report, 2010) was prepared and considered by the Select Committee prior to reporting back to the House. It provided a summation of the Select Committee proceedings, including a collation of all ‘key points’ raised by the public submission process presented to the Committee, as well as the recommendations regarding each issue by the relevant ministry's advisors. The eight public submissions received had raised concerns over the science supporting cryopreservation. For example, Dianne Yeats (mentioned previously as the promoter of the original Private Members Bill that became the HART legislation) observed:

My understanding is that the science is still out on the length of time embryos can be kept without deterioration. Interestingly, frozen peas have a ‘best used by date’ of usually not more than two years from the time of freezing.

Similar concerns were also mentioned in the submission by the New Zealand Nurses Organisation (NZNO Submission, 2010). The two statutory committees set up under the New Zealand HART Act to create policy and guidelines to support assisted reproductive technology (ACART) and to review ethical issues of non-standard application of IVF techniques [Ethics Committee on Assisted Reproductive Technology (ECART)] each made submissions. ACART supported the concept of a 10-year storage limit and raised additional issues relating to rights of children, adequacy of the science, and risks to offspring. ECART favoured ‘a flexible arrangement which leaves open the number of times an application for extension could be made’ (ECART Submission, 2010). Fertility Associates (a leading provider of IVF services) explored complexities in disposition decisions, such as disagreement between couples, which reflected their practical experience on these issues. In sum, the submitters supported a maximum permitted storage time, but those with practical experience of IVF (consumers, service providers) also argued for flexibility in the enforcement of the date and the right to appeal. None of the submissions reflected Māori interests in the issue.

Expert advice for the Health Select Committee was provided through the Initial Briefing, which is always prepared by officials associated with the department of the minister in charge of the bill (the Ministry of Justice in this case). A comment from Michael Woodhouse (MP) during the ‘in committee’ phase of the Bill's passage about this process notes:

We had a discussion that was more about the science behind that than about the time period, and we certainly had the advantage of not only the officials' counsel, but the chairman's counsel. The chairman [Dr Paul Hutchison] has a great deal of experience in this area from his professional [obstetrician and gynaecologist] background [Hansard NZ (In Committee) 2010b: 14099].

Thus, the discussion was framed around retaining the ‘status quo’ of fixed time limits on storage. The Initial Briefing (Ministry of Justice, 2010) uses the same two discourses, which were regularly appealed to throughout the parliamentary debates, to justify the undesirability of indefinite storage – ‘conflict avoidance’ and ‘build-up avoidance’. The latter related to concerns about the amount of reproductive material in storage, and was articulated through recourse to imagined scenarios such as the death of an embryo or gamete provider, or the dissolution of marriage, further bolstered with the anecdotal evidence that people ‘put off’ the decision to dispose of embryos due to the difficulty in making it (Initial Briefing, 2010: 4).

The previously mentioned Departmental Report provided no direct evidence relating to discourses of conflict or build-up avoidance as justification for a 10-year storage limit. The absence of any justification for storage demonstrates the Department's orientation in favour of the ‘status quo’ of mandated storage limits. For example, the Ministry of Justice dealt with Fertility NZ's (a leading fertility advocacy group) request for flexibility in storage times as follows:

The Ministry considers that acceptance of this proposal would weaken the protections provided by the storage limit (i.e. that extensions are carefully considered on a case by case basis) and would in turn undermine the policy intent of the Bill. (Select Committee Advice: Departmental Report 2010: 9).

Of note here is the word ‘protections’ and the fact that they do not elaborate or identify in detail what these protections are against. Similarly, the Ministry of Justice did not address Fertility NZ's request for an appeal process as they considered that this issue was ‘outside the scope of the Bill’ (Select Committee Advice: Departmental Report 2010: 9). In sum, this demonstrates that those with the authority to influence the drafting of the Bill were particularly conservative in their consideration of the storage period, taking its finite nature as a given.

The next discursive node appears when the Bill was returned to Parliament for its second reading on 7 September 2010. Here, the speakers reiterated what was said in the first reading, focusing largely on how the Bill was a technical bill that simply tidied, or clarified, a messy area of the legislation. Several MPs also noted that earlier concerns about the science of freezing and its possible side effects on embryos were now understood (subsequent to the committee discussions) to be invalid. Hone Harawira (MP) spoke about the necessity for the Bill to be reconsidered according to primary Māori concerns over storage and disposal, and the need for Māori to have ownership and control over this process. He was the only MP who specifically counteracted the focus on ‘technicalities’, and referred ‘to the wider field and the particular risks and concerns it poses for Māori’ [Hansard NZ (Debates) 2010a: 13722]. He posited that ‘the process used for the handing over of, the storage of, or the burial or cremation of embryos’ were ‘specially charged moments for Māori, and they need to be properly considered, managed, and handled in line with tikanga Māori [Māori customary practices]’ (ibid). He drew on Glover and Rousseau (2007) and on ACART's concerns for ‘collective discussion about cultural implications, kaitiakitanga [guardianship or management], and appropriate tikanga [customary practices] in its report’ [Hansard NZ (Debates) 2010a: 13722]. He also argued that ‘those eggs, those embryos those foetuses, those babies, belong to the whānau [family], not to the scientists’ (ibid). Thus, issues of the beginning of personhood are raised as well as that of ownership. He repeated his concern asking for discussion around ‘who owns them, whether or not they are destroyed, and how decisions are made about them’ [Hansard NZ (Debates) 2010a: 13722]. Finally, he expressed concern over whether reproductive technology is beneficial or spells ‘our demise as a people’, and the need for ‘the right of whānau [family] to be fully involved in all relevant decision-making … concerning their whakapapa [genealogy]’ and ‘over any of their own embryonic material’ (ibid). However, this was largely unacknowledged as MPs continued speaking to claim that this Bill was non-controversial. For instance, following after Hone Harawira's address, Jackie Blue said ‘This bill is not contentious’. Dr. Hutchison refers back to Flavell's earlier speech in the first reading of the Bill, beginning with the statement, ‘that it is vital that Māori are included’, but then insists that: ‘... the genesis of the original Human Assisted Reproductive Technology Act occurred over a long period of time – over a decade – and it involved ethicists, consumers, scientists, clinicians, psychologists, and lawyers. Eventually the Human Assisted Reproductive Technology Bill was enacted in 2004. I think it is also important to point out that the clinics, the consumers, and the clinicians have really not found any major problems with the Act at all…’ [Hansard NZ (Debates) 2010a: 13722]. The absence of Māori as an explicit consultation group within this list is striking, and shows the use of exclusion as a central feature of the ‘conflict avoidance’ discourse. David Parker's subsequent contribution demonstrates this dismissive engagement with Māori issues and is reproduced in Table 1.

Table 1.

Additional excerpts from Rahui Katene's speech on the third reading of the Human Assisted Reproductive Technology (Storage) Amendment Bill [Hansard NZ (Debates) 2010c: 14403].

| The ‘tikanga [customary practices] for destroying an embryo might take into account….’ |

| i) ‘The movement from living to not living’ |

| ii) ‘The preparation for burial, cremation etc.’ |

| iii) ‘The actual burial’ |

| iv) ‘The entry into the portals of the world of being and light’ |

| The ‘tikanga [customary practices] of gifting’; for when whānau [family] hand over their embryos and gametes…’ |

| i) ‘The sharing of whakapapa [genealogy]’ |

| ii) ‘The whakatau [or] settling process into the storage facility’ |

The Bill was subsequently passed from the second reading to the Committee of the Whole House with only the Māori Party opposing. When discussing the success of the amendments in giving clarity over storage length, Michael Woodhouse made an opaque reference to the ‘very dodgy ethical dilemmas’ produced through extremely long storage periods that had been considered recently in the UK House of Lords. The lack of specificity as to exactly what these dilemmas were was typical of the mind-set that fixed-term storage was in itself an ethical solution. There was one unusual comment, however, from Hon. Steve Chadwick in which she noted, ‘Those working in the field of human assisted reproductive technology do not like having to face the destruction of gametes…’; an explicit example of the social suffering the Bill would cause [Hansard NZ (Debates) 2010a: 13722].

After this, the Bill proceeded to its third and final reading, which spanned 2 days and was generally a repetition of points made previously. When voting occurred, only the Māori Party voted against it. Dr. Paul Hutchison (MP) directly critiqued the previous citation of Glover and Rousseau's (2007) work, stating it was ‘convoluted and inadequate’. He argued that ECART had Māori concerns at the ‘forefront’ of their guidelines, and that the Māori Party Members should not cite their own authorities, but rather the authoritative sources that Hutchison used himself. Rahui Katene from the Māori Party responded by arguing that:

it is one thing to talk about these matters; it is quite another to sit down and give expression to the tikanga [customary practices] that makes the words real [Hansard NZ (Debates) 2010c: 14458].

Rahui Katene explained that storing gametes and embryos was not simply a donation of biological material, but:

the handing over or passing over of a life-force. Such a tikanga [customary practices] provides a level of accountability and responsibility on the part of the agency to accept the Māori level of commitment. It also provides for the right of Māori to collect the embryo and gamete should the original agreement not be upheld.

Table 1 shows further issues raised by Rahui Katene.

Discussion

A good deal of public concern surrounding cryopreservation of embryos in New Zealand has focused on the unidentified assumed negativities of unchecked frozen embryo accumulation (Dominion, 2001, Dominion Post, 2004, Mayes, 2003, New Zealand Woman’s Weekly, 2004, Sunday Star Times, 2007, The Telegraph, 2010), as well as concerns about the imposition of mandated disposal (Little Treasures, 2014, New Idea, 2009, North and South, 2014, Otago Daily Times, 2014, Sunday Star Times, 2008). In this article, our close reading of the relevant parliamentary debates has failed to uncover recognizable ethical concerns that could explain the escalating publicly discussed unease about these accumulating embryos. Instead, the parliamentary rhetoric by those in favour of defining a maximum permissible storage time has most resembled (and frequently used) a language in which the regulatory discourse of tidy housekeeping best captures these undefined ethical concerns on embryo cryopreservation. These concerns were directed solely over the mounting stockpiles of frozen embryos. This is despite empirical studies about the difficulty of coming to terms with disposal, and the previously referenced local popular press concerns about the implementation of the 10-year freezing limit.

This is perhaps better understood, we argue, from the Pākehā legislator's perspectives as anxiety over ‘matter out of place’ (reflected in the examples in Table 1 of the ‘build-up avoidance discourse’ during parliamentary debate). Furthermore, the tone of the debate was speedy and business-like, such that all attempts to clarify and nuance the issues were quickly brushed aside (as described in the ‘conflict avoidance’ discourse). This rendered the topic of the time limit as unamenable to further contestation and negotiation. The necessity for speed was linked to the frequent and repeated references to the accumulating number of embryos, despite the continuing lack of accurate figures of frozen embryos, the failure to consider the small amount of space that such embryos physically occupy, and the unnoticed inflation of frozen eggs from the actual number of 68 to 68,000. This was a mistake that went unnoticed despite the self-satisfied ‘expertise’ on the issue of several of the parliamentarians. Highlights of these utterances are captured in Table 1. The social discomfort with this matter is somewhat like the Australian example, in which Stuhmcke (2014: 301) argues that the concerns over embryo accumulation were related to their apparent ‘purposelessness’. It also has similarities with the manner in which the creation of such embryos was understood as being in the dubious moral category of ‘abandoned’ in the Canadian example discussed by Cattapan and Baylis (2016).

The term ‘matter out of place’, which we argue best explains the New Zealand case study, draws on anthropologist Mary Douglas's work on the social meaning of dirt and its relationship to societal organization and general social mores (Douglas, 1966). Her work emphasizes the need to understand social history and cultural context before being able to explain the cultural logics behind seemingly arbitrary renderings of the sacred and the profane in concepts such as ‘waste’. Written in a period when anthropological theory neglected the complications of diversely constituted and cosmopolitan societies, it is still of relevance when considering the possibilities of various points of view on the meaning of reproductive ‘waste’ between indigenous and non-indigenous citizens in New Zealand. In Māoridom, reproduction itself is considered to be tapu (Le Grice and Braun, 2016), and this goes some considerable distance to explaining the unease and discomfort with Pākehā parliamentarians' consideration of embryo disposal as mundane, ordinary or unproblematic. In turn, the Pākehā legislators on this issue can also be understood to be responding to a distinctive world view.

A potent and very relevant local cultural logic has been noted by several New Zealand cultural studies theorists. Specifically, it is allied to the mentality of Christian Pākehā settlers to New Zealand who conflated moral wholesomeness with tidy and controlled landscapes leading to a cultural aesthetic in which, as Pawson (1987: 307) notes, ‘The imposition of order was thus central to the colonial enterprise’. In the local idiom of everyday New Zealand settler society, ‘tidy’ frequently appears in colloquial language with the contextualized meaning of ‘good’. In Egoz's (2000: 68) opinion, the legacy also remains today; for example, in the preferred management styles of rural farmlands where ‘messiness in the landscape carries social signals embedded in moral values’, and such signals carry connotations about industrialized Pākehā farming styles versus traditional Māori farming styles. These enduring cultural values are the cultural reason behind, we suggest, the recurring focus on the need to ‘tidy up’ embryo accumulation in the Pākehā contributions to the parliamentary debate.

If we make Pākehā cultural sense of cryopreserved embryos as ‘matter out of place’, then the rush to enforce mandatory storage is a culturally specific response to perceived moral and cultural risk, rather than any ethically argued moral principles for which, as previously noted, we have scoured relevant local publications and found none articulated. The imperative to accomplish this via the ‘conflict avoidance’ discourse frames the issues through a Pākehā cultural lens as closer to a minor moral panic (Cohen, 2002) where the authorities have responded to a threat to the imagined security of New Zealand's moral landscape with legislation. It is the speed with which the legislation was passed and the forceful quelling of any debate and delegitimation of Māori concerns as ‘outside’ of the artificially narrowed framework of discussion that is our basis for this view. The strong press for rapid consensus by Pākehā MPs on the need for storage that we have revealed, and the exaggerated anxieties of what they referred to as ‘dodgy’ but unidentifiable ethical problems associated with accumulation, further support this discursive reading. In Cohen's typology of the elements of a panic, the ‘folk devil’ would be the untidiness and clutter of steadily increasing numbers of frozen embryos, while the ‘suitable victims’, which Cohen (2002: xii) notes as having the qualities of ‘someone with whom you can identify, someone who could have been and one day could be anybody’, are the cryopreserved embryos.

The outcome of these cultural anxieties has been the enforcing of a maximum permissible storage time for cryopreserved embryos of 10 years, with the paradoxical effect of increasing social suffering as people respond to the imposition of the limit which we set out in detail in our earlier review. Jackson (2016) notes a similarly perverse set of outcomes for female clients, subject to the newly revised mandatory freezing limits for eggs created through IVF in the UK. In this instance, women have been denied the opportunity to store eggs in their early 30s for use in their later 40s, because reduced fertility at that age is the usual biological life course event and therefore outside the scope of reasons for allowing increased storage times (Jackson, 2016). As both Simpson (2013) and Haimes and Taylor (2011) have noted, legislative rules and bureaucratic decision-making around reproduction and cryopreservation in particular are not neutral endeavours.

In the New Zealand situation, two additional groups stand out as being unfairly affected by the changing regulations. The first are the IVF clinic staff, who have shouldered the ethical burdens of undertaking this large-scale embryo destruction. Our previous work (Fitzgerald et al., 2013, Fitzgerald and Legge, 2017) with New-Zealand-based embryologists has highlighted the emotional care they invest in the embryos and clients, and their concern for the process of disposition. This is an under-recognized aspect of such laboratory work generally, and was also noted by Ehrich et al. (2008) and Pickersgill (2012). The implementation of the 10-year cryopreservation limit simply shifts the ethical dilemmas on to the shoulders of those who must translate the legislation into action, but whose ethical qualms are not reported.

However, the final and largest group affected in New Zealand is the indigenous citizens who, as a group, hold a special and legally recognized relationship with place through the Treaty of Waitangi (Ministry of Justice, 2017). Glover and Rousseau's (2007) discussion of Māori views on reproductive technology which involved 15 interviews and six hui [gatherings, or open discussions with various key constituencies] indicates a complex diversity of Māori views on the spiritual, social and political ramifications of the technology, although there was no reported discussion of the implications of cryopreservation. More recently, a variety of Māori views relating to IVF technology have begun to emerge (Hiroti, 2011, Reynolds and Smith, 2012), although, again, the issues related to disposition and long-term storage have not been discussed explicitly. We suggest, however, that these issues are complex and involve far more than merely administrative formalities, particularly a different set of cultural anxieties compared with those expressed by the Pākehā parliamentarians. Katene raises an overview of some considerations required while dealing with such a practice. For example, the importance of the understanding by Māori that an embryo is ‘living’ or, in the case of cryopreservation, has the potential for life and the inheritance of Māori rights, then sets up the need for whānau [family] or even wider hapū [subtribe] involvement and decision-making around disposal and ‘actual burial’. It also raises the need for careful consideration in addressing the cultural sensitivity around the location to which the embryo is cryopreserved or buried, the cultural observations around preservation or burial, and the relocation or dislocation of a ‘genetic member’ of a whānau [family] or hapū [subtribe]. As one example of these complexities, we consider Katene's use of the term ‘whakatau’. This is a term that ranges in application. ‘Whakatau’ generally refers to the rendering of a state of feeling spiritually, emotionally, psychologically, culturally and physically settled, content, familiar or comfortable, rather than feeling uneasy, anxious, strange or even mildly uncomfortable. In considering cryopreservation, the whakatau process may well apply throughout all stages; that is, when cryopreservation was actually being considered, the cryopreservation process itself, through to disposal of the embryo. It is important that the psychological, emotional, spiritual and cultural components are considered in advance in order to make the process as comfortable and appropriate as possible, thereby allowing the process to be safely negotiated by and for all parties concerned, particularly the IVF centre and the donor (as biological parents), or, on occasion, the extended whānau [family] and hapū [subtribe]. For the donor, this might require having whānau support in place during the discussions and decision-making, should the donor choose. Whakatau, in this context, refers to the provision of an environment and process that assists the parties to discuss the pertinent issues and reach a decision with which they are fully content.

The next phase, the storage and physical location of the embryo, then needs to be considered, again taking into account the tikanga [customary practices] involved in its deposit there. When considering this, the Māori concepts tapu and noa become important as they inform and affect the application of tikanga [customary practices] (Reilly et al., 2018). Tapu is a concept which relates to things that are sacred or forbidden, having restriction, or being afforded a special deference and respect. Noa relates to the state free from extensions of tapu. Although tapu is often associated with death, in discussing cryopreservation, tapu would be better contextualized with respect and acknowledgement as afforded to a living person; this might also extend to how the embryo is being handled. The disposal of the embryo takes on another dimension, and how this is tended to may require another thought process around customary practice; one that is cognisant of death. When Māori deal with the deceased, the embryo is moving from the physical realm to the spiritual realm; therefore, things such as karakia [ritual chants] might be delivered in order to release the spirit from the embryo as it is interred, just as Māori would while burying the deceased. It is important to note that the discussion above regarding Māori may not apply to all Māori, and that the adherence to custom, as discussed, depends on how engaged Māori are with their culture.

What we are seeing politically in these debates is two different ways (Māori and Pākehā) of organizing society, acts of reproduction and the complex social relationships created, in part, through cryopreservation. Our analysis of these related parliamentary and public debates shows no engagement with any of these Māori concerns over these spiritual and cultural relationships. Humpage (2017) has also noted a similarly superficial engagement in New Zealand Government social policy formation with Māori concerns. This lack of broad community engagement in the Pākehā-dominated legislative process stands in stark and ironic contrast to the more inclusive and dialogical approaches to decision-making within Māoridom.

We conclude then that appreciating ethical concerns about embryo disposition requires researchers to explore the background cultural context of people's personal decision-making strategies, and the wider cultural logics powering the regulatory responses to the embryo's ambiguous status. The current literature on embryo disposal ignores the wider political context in which such decision-making occurs, treating decision-making as a highly individualized activity. Without this wider cultural political context, we hear only a portion of the diverse complexities and viewpoints into the moral dilemmas of embryo disposition. Furthermore, the ethical justification for finite storage periods (in those countries where they are enforced) remain unarticulated, while the existing literature demonstrates when read ‘against the grain’ that there is ample evidence of the anguish produced when disposition decisions are required. In New Zealand, it seems likely that the recent widespread disposal of embryos (approximately 2000 were deemed not to fit the legal criteria for longer storage) has been associated with significant but unrecorded social suffering as the referenced popular media articles would suggest. Thus, we agree with Haimes and Taylor (2011) that the technique of cryogenic storage is not a neutral tool, and its use has created ethical difficulties in itself (Jackson, 2016). While mandated storage limits appear to have alleviated the state's anxiety over accumulation of cryopreserved ‘spare’ embryos, this has been accomplished by simply shifting the ethical burden of disposal on to those individual clients for whom an undefined storage limit was preferable, wider Māoridom and scientific workers – all of whose private suffering has still to be publicly acknowledged.

In exposing the lack of appropriate representation of indigenous viewpoints in the making of New Zealand legislative decisions over cryopreservation limits, we demonstrate how this becomes a serious ethical issue through a lack of distributive justice accorded to the senior Treaty Partners in the Treaty of Waitangi. While disposal decision-making is always difficult, this should not be a reason for adding the additional issues of representational injustice to people's already heavy burdens. The problem of lack of attention (and outright exclusion of the Māori world view) through the legislation-making process towards Māori concerns could be ameliorated by allowing consideration of unlimited storage in certain cases, with cultural sensitivities to the understanding of embryos as waste being able to be recognized as a possible route for abstention from mandated disposal. It is notable that this is in accordance with all the requested and subsequently ignored amendments to the Bill during its passage through Parliament from all parties who had any direct involvement in engaging in the provision of fertility services with diverse clients. If this has been the case for our New Zealand case study, this research begs the question of the significance of cultural concerns from other indigenous communities around the world in relation to embryo disposal.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the Wenner Gren Foundation for partly funding the assistant researcher on this project. This work has been improved by the insightful comments of our anonymous reviewers.

Biography

Ruth Fitzgerald is a Professor of Social Anthropology at the University of Otago where she teaches and researches in the field of medical anthropology. Her specialist research interests are genetics, embodiment, moral reasoning, and ideologies of health and human reproduction. In 2018, she received a national teaching award for excellence in tertiary teaching, and prior to that, she was a recipient of the Te Rangi Hiroa medal awarded by the New Zealand Royal Society for research in medical anthropology. Ruth is also Chair of the Editorial Board of Sites, and Australasian Regional Editor for Teaching Anthropology.

Declaration: The authors report no financial or commercial conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

This has resulted in extremely lengthy consent forms for engaging in IVF procedures in New Zealand. Participants often find these consent forms challenging to complete due to the detail and variety of unanticipated possible consequences that they are required to imagine. This conservativism in imagined family impacts of IVF was first noted by Mulkay (1994) in his discussion of social debates around embryo research in the UK.

Translator's note. Related to this, Māori refer to an ‘ātua kahukahu’ as the spirit entity that is responsible for stillbirth or other detrimental effects on the unborn embryo or fetus. Some sources (e.g. http://rsnz.natlib.govt.nz/volume/rsnz_37/rsnz_37_00_000330.html) refer to the ātua kahukahu as a malign entity; however, the term ‘malign’ is possibly open to interpretation. Kahu sometimes refers to the membrane around the fetus.

References

- Afshar L., Bagheri A. Embryo Donation in Iran: an ethical review. Dev. World Bioeth. 2013;13(3):119–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8847.2012.00334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcoff L. Gender and Reproduction. Asian J. Women's Stud. 2008;14(4):7–27. [Google Scholar]

- Cattapan A., Baylis F. Frozen in perpetuity: ‘abandoned embryos’ in Canada. Reprod. Biomed. Soc. Online. 2016;1:104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.rbms.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. 3rd ed. Routledge; Oxford England: 2002. Folk devils and moral panics: The creation of the Mods and Rockers. [Google Scholar]

- Colen S. With Respect and Feelings’: Voices of West Indian Child Care Workers in New York City. In: Cole J.B., editor. All American Women: Lines That Divide, Ties That Bind. Free Press; New York: 1986. pp. 46–70. [Google Scholar]

- de Lacey S. Parent identity and ‘virtual’ children: why patients discard rather than donate unused embryos. Hum. Reprod. 2005;20(6):1661–1669. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominion . 2001. ‘Adopting the Unborn’ 26 March 2001; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Dominion Post . Australian Fairfax Group; Wellington NZ: 2004. Dilemma of life in cold storage. (31 May p B6) [Google Scholar]

- Douglas M. Routledge; London and New York: 1966. Purity and Danger: An analysis of the concepts of pollution and taboo. [Google Scholar]

- ECART Submission 2010. https://www.parliament.nz/en/pb/sc/submissions-and-advice/document/49SCHE_EVI_00DBHOH_BILL9694_1_A35839/ethics-committee-on-assisted-reproductive-technology

- Edwards R.G., Beard H.K. Destruction of cryopreserved embryos. Hum. Reprod. 1997;12:3–11. doi: 10.1093/humrep/12.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egoz S. Clean and green but messy: The contested landscape of New Zealand's organic farms. Oral Hist. 2000;28:63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrich K., Williams C., Farsides B. The embryo as moral work object: PGD/IVF staff views and experiences. Sociol. Health Illn. 2008;30(5):772–787. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2008.01083.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald R.P., Legge M. Ethics for Embryologists. In: Shaw R., editor. Bioethics Beyond Altruism: Donating and Transforming Human Biological Materials. Palgrave MacMillan; UK: 2017. pp. 141–164. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald R.P., Legge M., Frank N. When biological scientists become health-careworkers: emotional labour in embryology. Hum. Reprod. 2013;28(5):1289–1296. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg F., Rapp R. The Politics of Reproduction. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 1991;20:311–343. doi: 10.1146/annurev.an.20.100191.001523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover M., Rousseau B. Your child is your whakapapa: Maori considerations of assisted human reproduction and relatedness. Sites. 2007;4(2):117–136. [Google Scholar]

- Glover M., McCree A., Dyall L. An exploratory study, School of Population Health, University of Auckland; 2008. Māori Attitudes to Assisted Human Reproduction; pp. 95–98.http://www.maramatanga.co.nz/project/m-ori-and-assisted-human-reproduction-exploratory-study Available @. [Google Scholar]

- Goswami M., Murdoch A., Haimes E. To freeze or not to freeze embryos: clarity, confusion and conflict. Hum. Fertil. 2015;18(2):113–120. doi: 10.3109/14647273.2014.998726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haimes E., Taylor K. The contributions of empirical evidence to socio-ethical debates on fresh embryo donation for human embryonic stem cell research. Bioethics. 2011;25(6):334–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8519.2009.01792.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haimes E., Porz R., Scully J., Rehmann-Sutter C. ‘So what is an embryo?’ A comparative study of the views of those asked to donate embryos for hESC research in the UK and Switzerland. New Genet. Soc. 2008;27(2):113–126. doi: 10.1080/14636770802077041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansard NZ (Debates) Human Assisted Reproductive Technology (Storage) Amendment Bill — First Reading, 8 Dec 2009, Vol 659, Page 8335. 2009. https://www.parliament.nz/en/pb/hansard-debates/rhr/document/49HansD_20091208_00000935/human-assisted-reproductive-technology-storage-amendment [Online], available:

- Hansard NZ (Debates) Human Assisted Reproductive Technology (Storage) Amendment Bill — Second Reading, 7 Sep 2010, Vol 666, Page 13722. 2010. https://www.parliament.nz/en/pb/hansard-debates/rhr/document/49HansD_20100907_00000392/human-assisted-reproductive-technology-storage-amendment [Online], available:

- Hansard NZ (Debates) Human Assisted Reproductive Technology (Storage) Amendment Bill – In Committee, 16 Sep 2010, Vol 666, Page 14099. 2010. https://www.parliament.nz/en/pb/hansard-debates/rhr/document/49HansD_20100916_00001072/human-assisted-reproductive-technology-storage-amendment [Online], available:

- Hansard NZ (Debates) Human Assisted Reproductive Technology (Storage) Amendment Bill — Third Reading, 12 Oct 2010, Vol 667, Page 14403. 2010. https://www.parliament.nz/en/pb/hansard-debates/rhr/document/49HansD_20101012_00001122/human-assisted-reproductive-technology-storage-amendment [Online], available:

- Hansard NZ (Debates) Human Assisted Reproductive Technology (Storage) Amendment Bill — Third Reading, Resumed, 13 Oct 2010, Vol 667, Pages 14458. 2010. https://www.parliament.nz/en/pb/hansard-debates/rhr/document/49HansD_20101013_00001146/human-assisted-reproductive-technology-storage-amendment [Online], available:

- Hansard UK Human Fertilization and Embryology (Warnock Report). HC Deb. 23 November 1984, vol.68, cc528-44 [Online] 1984. http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/commons/1984/nov/23/human-fertilisation-and-embryology available:

- Hiroti L.P., editor. He Kākano: a collection of Māori experiences of fertility and infertility. Te Atawahi o te Ao. Independent Māori Institute for Environment & Health; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Humpage L. Does having an Indigenous Political Party in Government make a Difference to Social Policy? The Māori Party in New Zealand. J. Soc. Policy. 2017;46(3):475–494. [Google Scholar]

- IFFS . 7thed. 2016. Federation of Fertility Societies.http://www.iffs-reproduction.org/?page=Surveillance Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Jackson E. ‘Social’ egg freezing and the UK's statutory storage time limits. J. Med. Ethics. 2016:2016. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2016-103704. (Published Online First: August 23) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X., Xianwang G., Liu S., Liu M., Zhang J., Shi Y. Patients' Attitudes towards the Surplus Frozen Embryos in China. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2013/934567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonlin E.C. The voices of embryo donors. Trends. Mol. Med. 2015;21(2):55–57. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpin I., Millbank J., Stuhmcke A., Chandler E. Analysing IVF Participant Understanding of, Involvement in, and Control over Embryo Storage and Destruction. Aust. J. Law Med. 2013;20:811–820. [Google Scholar]

- Kato M., Sleeboom-Faulkner M. Meanings of the embryo in Japan: narratives of IVF experience and embryo ownership: IVF experience and embryo ownership in Japan. Sociol. Health Illn. 2011;33(3):434–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2010.01282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindregan C., McBrien M. Assisted Reproductive Technology: A look at the disposition of embryos in divorce. Fam. Lawyer Mag. 2013:54 +. (July 23) [Google Scholar]

- Le Grice J., Braun V. Matauranga Maori and Reproduction. Inscribing connections between the natural environment, kin and the body. Alternative. 2016;12(2):151–164. [Google Scholar]

- Little Treasures . 2014. ‘Expiry Anxiety’ Little Treasures Mar/April 2014. N 161; pp. 54–55. [Google Scholar]

- Lyerly A., Steinhauser K., Namey E., Tulsky J., Cookdeegan R., Sugarman J., Walmer D., Faden R., Wallach E. Factors that affect infertility patients' decisions about disposition of frozen embryos. Fertil. Steril. 2006;85(6):1623–1630. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyerly A.D., Steinhauser K., Voils C., Namey E., Alexander C., Bankowski B., Cook-Deegan R., Dodson W., Gates E., Jungheim E. Fertility patients' views about frozen embryo disposition: results of a multi-institutional U.S. survey. Fertil. Steril. 2010;93(2):499–509. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyerly A., Nakagawa S., Kupperman M. Decisional Conflict and the Disposition of Frozen Embryos: Implications for Informed Consent. Hum. Reprod. 2011;26(3):646–654. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayes Gwen. Medscape; 2003. Frozen in Time: Disposition of Frozen Embryos gives Rise to Ethical, Legal and yes,….. Political Considerations. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/456483

- McLauchlan L., Park J. ‘Quiet as lambs’: Communicative Action in the New Zealand Parliamentary Debates on Human Assisted Reproductive Technology. Sites. 2010;7(1):101–122. [Google Scholar]

- Melamed R.M.M., Bonetti T., Braga D., Madaschi C., Iaconelli A., Borges E. Deciding the fate of supernumerary frozen embryos: parents' choices. Hum. Fertil. 2009;12(4):185–190. doi: 10.3109/14647270903377186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health 2018. https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/populations/maori-health/he-korowai-oranga/strengthening-he-korowai-oranga/treaty-waitangi-principles

- Ministry of Justice Human Assisted Reproductive Technology (Storage) Amendment Bill – Initial Briefing, MLE 01 07, 1–6, [Online] 2010. https://www.parliament.nz/resource/en-NZ/49SCHE_ADV_00DBHOH_BILL9694_1_A36095/83ef3b8804a9f7c4a82f4725a078c43533d1a8f9 available:

- Ministry of Justice The Treaty of Waitangi/Te Tiriti o Waitangi. 2017. https://www.waitangitribunal.govt.nz/

- Mulkay M. Science and Family in the Great Embryo Debate. Sociology. 1994;28(3):699–715. doi: 10.1177/0038038594028003004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachtigall R.D., Becker G., Friese C., Butler A., MacDougall K. Parents' conceptualization of their frozen embryos complicates the disposition decision. Fertil. Steril. 2005;84(2):431–434. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.01.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachtigall R.D., MacDougall K., Harrington J., Duff J., Lee M., Becker G. How couples who have undergone in vitro fertilization decide what to do with surplus frozen embryos. Fertil. Steril. 2009;92(6):2094–2096. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New Idea . Pacific Magazines; Auckland NZ: 2009. Fighting for My Babies; pp. 26–27. [Google Scholar]

- New Zealand Woman’s Weekly . 2004. ‘What should we do with our frozen babies?’Wellington NZ 31 May 2004; p. B6. [Google Scholar]

- Nie J.-B., Fitzgerald R., editors. Methodologies of Transcultural Bioethics. 26(3) Kennedy Institute of Ethics; 2016. pp. 219–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North and South . 2014. ‘Last Chance for Life’. Oct 2014 n 343; pp. 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- NZNO Submission 2010. https://www.parliament.nz/en/pb/sc/submissions-and-advice/document/49SCHE_EVI_00DBHOH_BILL9694_1_A36109/new-zealand-nurses-organisation

- Otago Daily Times 2014 ‘Baby Odyssey: familiar face to call their own; Expiry date looms for frozen embryos; Legislated time limit. Otago Daily Times 26 July 2014 p 13.

- Park J., McLauchlan L., Frengley E. 2008. Normal Humanness, Change and Power in Human Assisted Reproductive Technology: An Analysis of the Written Public Submissions to the New Zealand Parliamentary Health Committee in 2003 Research in Anthropology & Linguistics – e Number 2 University of Auckland, Auckland New Zealand. [Google Scholar]

- Paul M.S., Berger R., Blyth E., Frith L. Relinquishing Frozen Embryos for Conception by Infertile Couples. Fam. Syst. Health. 2010;28(3):258–273. doi: 10.1037/a0020002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips J. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand; 2015. The New Zealanders - ‘Where Britain goes, we go.http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/the-new-zealanders/page-8 [Google Scholar]

- Pickersgill M. The Co-production of Science, Ethics, and Emotion. Human Values.;Sci. Technol. Hum. Values. 2012;37(6):579-60. [Google Scholar]

- Pihama L. Experiences of Whanau Maori within Fertility Clinics. In: Reynolds P., Smith C., editors. The Gift of Children: Maori and Infertility. Hui Publishers; Wellington: 2012. pp. 203–234. [Google Scholar]

- Pawson E. 'Order and Freedom: A Cultural Geography of New Zealand. In: Holland P., Johnston W., editors. Southern Approaches: Geography in New Zealand. New Zealand, Geographical Society; Christchurch: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Provoost V., Pennings G., De Sutter P., Dhont M. The frozen embryo and its nonresponding parents. Fertil. Steril. 2011;95(6):1980–1984. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provoost V., Pennings G., De Sutter P., Dhont M. ‘Something of the two of us’. The emotionally loaded embryo disposition decision making of patients who view their embryo as a symbol of their relationship. Gynecology.;J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012;33(2):45–52. doi: 10.3109/0167482X.2012.676111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly M., Duncan S., Leoni G., Paterson L., Carter L., Ratima M., Rewi P., editors. Te Kōparapara. Auckland University Press; Auckland: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds P. Tāne Maori, fertility and infertility. In: Reynolds P., Smith C., editors. The Gift of Children: Māori and Infertility. Huia; Wellington: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds P., Smith C. Huia Publishers; Wellington: 2012. The Gift of Children: Maori and Infertility. [Google Scholar]

- Righarts A., Dickson N.P., Parkin L., Gillett W.R. Infertility and outcomes for infertile women in Otago and Southland. N. Z. Med. J. 2015;128(1425) https://www.nzma.org.nz/journal/read-the-journal/all-issues/2010-2019/2015/vol-128-no-1425-20-november-2015/6724 Available @. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts E.F.S. Abandonment and Accumulation: Embryonic Futures in the United States and Ecuador. Med. Anthropol. Q. 2011;25(2):232–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1387.2011.01151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosemann A. Modalities of value, exchange, solidarity: the social life of stem cells in China. New Genet. Soc. 2011;30(2):181–192. [Google Scholar]

- Select Committee Advice: Departmental Report for Human Assisted Reproductive Technology (Storage) Amendment Bill. 2010. https://www.parliament.nz/en/pb/sc/submissions-and-advice/document/49SCHE_ADV_00DBHOH_BILL9694_1_A44496/departmental-report#RelatedAnchor

- Simpson B. Managing Potential in Assisted Reproductive Technologies. Reflections on Gifts, Kinship, and the Process of Vernacularization. Curr. Anthropol. 2013;54(7):S87–S96. [Google Scholar]

- Stone L. Kinship and Gender: An Introduction. 5th ed. Routledge; New York: 2018. Gender, Reproduction, and Kinship; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sunday Star Times . 2007. ‘Ice Storm’. 15 Feb 2007; p. C1.4. [Google Scholar]

- Sunday Star Times . 2008. ‘The Gift of Life’. 3 Aug 2008; p. C4. [Google Scholar]

- Svendsen M.N., Koch L. Unpacking the ‘Spare Embryo’: Facilitating Stem Cell Research in a Moral Landscape. Soc. Stud. Sci. 2008;38(1):93–110. [Google Scholar]

- The Telegraph . 2010. IVF: the hidden story of Britain's snowbabies. (23 Aug) [Google Scholar]

- Wardell S., Fitzgerald R.P., Legge M., Clift K. A qualitative and quantitative analysis of the New Zealand media portrayal of Down syndrome. Disabil. Health J. 2014;7:242–250. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnock Committee . HMSO; 1984. The Report of the Committee of Inquiry into Human Fertilization and Embryology. [Google Scholar]

- Wetherell M., Yates S., Taylor S. Sage in association with The Open University; London. Thousand Oaks [Calif.]: 2001. Discourse Theory and Practice: A Reader. [Google Scholar]

- Williams C., Wainwright S., Ehrich K., Michael M. Human embryos as boundary objects? Some reflections on the biomedical worlds of embryonic stem cells and pre-implantation genetic diagnosis. New Genet. Soc. 2008;27(1):7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wodak R., Chilton P.A., editors. A New Agenda in (Critical) Discourse Analysis: Theory, Methodology, and Interdisciplinarity. J. Benjamins Pub. Co.; Philadelphia: 2007. [Google Scholar]