Abstract

Level systems have been described as a framework which can be used to shape behavior through the systematic application of behavioral principles. Within level systems, an individual moves up and down through various levels contingent upon specific behaviors. Although level systems are commonly used within schools and other settings, they have a limited empirical literature base, and there is debate over the efficacy and overall acceptance of level systems. More especially, there is scant empirical literature on the use level systems to improve socially significant behaviors (e.g., synchronous engagement) with individuals diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of a level system with a structured, yet flexible approach to movement on improving synchronous engagement with two dyads of children diagnosed with ASD. The results of an ABAB reversal design indicated that the level system was effective at improving synchronous engagement for both dyads. The results are discussed in relation to potential future research difficulties and clinical implications.

Keywords: Level system, Flexible, Shaping, Feedback, Autism, Engagement

A level system has been described as a framework which can be used to shape behavior through the systematic application of behavioral principles (Smith & Farrell, 1993). A level system commonly combines multiple behavior change techniques such as the use of positive reinforcement, contingency contracting, response cost, shaping, and fading (Bauer, Shea, & Keppler, 1986; Smith & Farrell, 1993), while others have described a level system as a fading step within a token economy (Cooper, Heron, & Heward, 2007; Kazdin & Bootzin, 1972). Within this type of level system, an individual moves up and down slowly (e.g., over days and weeks) and there is a loose relationship between any specific response and an increase or decrease in immediately available reinforcers (Cooper et al., 2007; Kazdin & Bootzin, 1972). Furthermore, each level corresponds with a different overall standard of behavior and a corresponding level of entitlement to privileges.

Although level systems are commonly used within schools and other settings, they have a limited empirical literature base (Farrell, Smith, & Brownell, 1998; Smith & Farrell, 1993), and there is debate over the efficacy and overall acceptance of level systems within public schools (Farrell et al., 1998; Mohr, Martin, Olson, Pumariega, & Branca, 2009). While the research evaluating level systems is limited, there are a few recent empirical investigations. For instance, Hagopian et al. (2002) examined the efficacy of an individualized level system to decrease the rate of problem behavior exhibited by four individuals diagnosed with developmental disabilities. Each level system was individualized based on a functional analysis prior to intervention and ranged between two and three levels and was implemented in a one-to-one setting. Within the three tiered level system, level 3 generally consisted of dense schedules of reinforcement based on information from the functional analysis (e.g., frequent praise if the functional analysis indicated that attention was the maintaining variable for the challenging behavior). Level 2 indicated non-exclusionary time-out, in which the items available in level 3 were not available. Level 1 consisted of time-out in a separate room (i.e., exclusionary time-out). All participants started at level 3, and movement down through the levels was contingent upon the presence of challenging behavior. Movement back up the levels was contingent upon the absence of challenging behavior for a specific period of time. The results indicated the individualized level systems were efficacious at reducing the rate of challenging behavior for all four participants.

Gonzalez, Taylor, Borrero, & Sangkavasi (2013) examined the efficacy of an individualized level system to improve independent mealtime behavior for two children with various disabilities. The level system consisted of two levels for both children: one level to signal access to a high preferred item and one level to signal access to a less preferred item (the items were determined through a paired-choice preference assessment). Movement between levels was determined based on the number of prompts required to eat or prompts plus packs (i.e., larger than a pea-sized piece of food in the child’s mouth 30 s after a bite had been taken). That is, if the number of prompts or prompts plus packs, exceeded a predetermined number, the child moved down a level. Once a child moved down a level, there was no criterion for moving back up. Instead, the child remained on the lowest level until the next meal in which the child began at the highest level. The results of a reversal design indicated that the level system was effective in improving independent mealtime behavior for both participants.

To date, the authors are aware of only one study that has utilized a level system with individuals diagnosed with ASD. Leaf et al. (2017) incorporated an individualized level system within a behaviorally based social skills group. The level system involved five levels (i.e., “Superkid,” “Awesome,” “Okay,” “Warning,” and “Miss out on a fun activity”). Each participant had a clip with her or his name signaling his or her current level. Unlike previous studies, there were no previously determined rules for movement up or down through the levels. Instead, the interventionists had flexibility in determining movement which “was generally contingent upon the current targets as well as each individual’s overall social behavior” (Leaf et al., 2017, p. 249). Also, movement could occur within a level (e.g., moving from the bottom of Awesome to the top of Awesome) or across levels (e.g., moving from Okay to Warning). Miss out on a fun activity consisted of non-exclusionary time-out in which the participant observed his or her peers engaging in a fun activity. At the end of each session, if a child ended on the Superkid level, s/he could take a small toy home. The evaluation of the level system was not Leaf and colleagues’ purpose, but the overall results of the behaviorally based social skills group were highly significant across all three assessments (i.e., the Social Skills Improvement System, the Social Responsiveness Scale, and the Walker–McConnell Scale of Social Competence and School Adjustment). However, the efficacy of the level system alone with children diagnosed with ASD remains unknown.

While the aforementioned studies are promising, the literature on the effectiveness of level systems to improve socially significant behaviors for individuals diagnosed with ASD, and others, remains limited. One potential socially significant behavior with limited research is synchronous engagement (Vernon, Koegel, Dauterman, & Stolen, 2012). Synchronous engagement represents an attempt to evaluate the mutually reinforcing interactions among at least two individuals. Synchronous engagement differs from typical measures of engagement by including measures of simultaneous favorable affect as an indicator of the enjoyment. Synchronous engagement requires two individuals “simultaneously directing positive affect at one another while engaged in the same activity” (Vernon, Koegel, Dauterman, & Stolen, 2012, p. 7). Some have suggested that synchronous engagement can be critical in development, accelerate learning, and that the presence of synchronous engagement demonstrates the value of an interactive experience (Vernon et al., 2012). In one of the earliest studies including synchronous engagement as a dependent measure, Vernon et al. (2002) examined the effects of training parents to implement a social engagement intervention with three parent-child dyads. The training involved instructing parents to implement pivotal response training (PRT) social-communicative opportunities as well as embedding social interactions with reinforcing stimuli. The results indicated that the intervention was effective at improving synchronous engagement across all three dyads.

Given the potential benefits of level systems (e.g., flexibility in determining movement; Leaf et al., 2017) and the limited research on the use of level systems to improve socially significant behavior for individuals diagnosed with ASD, more research is necessary. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of a level system with a structured, yet flexible approach to movement on improving synchronous engagement with two dyads of children diagnosed with ASD.

Method

Participants

A total of four children participated in the study. The children were assigned to two different dyads. Will and MacKenzie were assigned to dyad 1. Will was a 7-year-old boy with an independent diagnosis of ASD. Will had an IQ of 72, a score of 69 on the Vineland-II Adaptive Behavior Scales, and a score of 86 on the Social Skills Improvement System. He had been receiving intervention based on the principles of applied behavior analysis (ABA) for approximately 1 year upon beginning the study. Will spoke in full sentences to communicate his wants and needs, engaged in moderate to low levels of stereotypic behavior (e.g., hand flapping, talking about the same topic for long periods of time), displayed limited social skills when compared to same aged typically developing peers, and had no experience with a level system prior to the study. MacKenzie was a 5-year-old girl with an independent diagnosis of ASD. MacKenzie had an IQ of 72, a score of 65 on the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, and a score of 74 on the SSiS. She had also been receiving intervention based on the principles of ABA for approximately 1 year upon beginning the study. MacKenzie spoke in full sentences to communicate her wants and needs, engaged in moderate to low levels of stereotypic behavior (e.g., talking to herself about specific topics), displayed limited social skills, and had no experience with a level system prior to the study.

Dyad 2 consisted of Jim and Maggie. Maggie was a 5-year-old girl with an independent diagnosis of ASD. Maggie scored 80 on the Vineland-II Adaptive Behavior Scales and 67 on the Social Skills Improvement System. She had been receiving intervention based on the principles of ABA for approximately 2 years upon beginning the study but had no experience with a level system prior to the study. Maggie communicated using full sentences and did not engage in behavior that would be classified as stereotypic. Her main behavior deficits were in the social skills domain, and most of her programming within the clinic consisted of social skills interventions. Jim was a 5-year-old boy with an independent diagnosis of ASD. Jim had an IQ of 130, a score of 99 on the Vineland-II Adaptive Behavior Scales, and a score of 67 on the Social Skills Improvement System. He had been receiving intervention based on the principles of ABA for approximately 2 years upon beginning the study but had no experience with a level system prior to the study. Jim’s main behavior deficits were in the social skills domain, and most of the programming he received consisted of social skills interventions.

Interventionist

Given the use of the flexible shaping, the experience, knowledge of the participants and population, and competencies with the principles used within such an approach of the interventionist may be important for application and replication. The first author served as the interventionist for all intervention sessions. At the time of the study, he had an undergraduate degree in special education, master’s degree in behavior analysis, and was a doctoral student in an applied behavior analysis program. He had over 10 years of experience providing intervention based on the principles of behavior analysis for individuals diagnosed with ASD. However, he had limited to no experience providing intervention for any of the participants within this study.

Setting and Materials

All sessions were conducted in a room (4.5 × 5.3 m) located within a private clinic in Southern California that provides intervention based on the principles of behavior analysis for individuals diagnosed with ASD. The room included a child-sized table, two child-sized chairs, adult-sized office chairs, video camera, toys/toy sets (described below), treasure chest (described below), level system (described below), other furniture (e.g., desks, bookcases, and a couch), and various instructional materials (e.g., toys, felt board, and computers). Sessions occurred once per day up to five times per week, based on participant availability. All sessions lasted approximately 5 min and were videotaped for scoring after each session.

Six toys/toy sets were selected for each dyad. The toys/toy sets were selected based on age appropriateness, peer interest (i.e., toys similar to those which same aged peers engaged), and could set the occasion for interaction (i.e., toys that are typically played with alone were avoided). The toys/toy sets were rotated across sessions and none were available outside of research sessions. Toys for dyad 1 consisted of Legos®, Light Sabers™, Gooey Louie™, Disney Pixar Cars Race Track, Iron Man set, and Nerf Guns. Toys for dyad 2 consisted of Legos®, Disney’s Frozen action figures, super hero action figures, race cars, Don’t Break the Ice®, and Light Sabers™. Prior to each session, five of the six toys/toy sets were arranged on the tables in the room. Several toys, other than those arranged and previously described, were placed inside a toy treasure chest (e.g., princess stickers, silly putty, sticky hands, plastic bracelets). These toys were selected based on child preferences identified through observation and interviews with the children’s staff, supervisors, and caregivers. These toys were available during intervention based on which level of the level system the child was on at the end of the session.

Level System

The level system (see Fig. 1 for a picture) was similar to the system Leaf et al. (2017) described. The visual reinforcement system consisted of three tiers. The bottom tier “Miss out on a fun activity” indicated that the child did not earn access to the treasure chest to play with a toy once the session ended. The middle tier “Friend” indicated that the child earned 2 min of access to the treasure chest at the end of the session but could not take the item from the treasure chest home. The top tier “Super friend” indicated that the child earned 2 min of access to the treasure chest at the end of the session and could take the item from the treasure chest home after already having access to the item. Each child in the dyad had a clip with her/his name or picture clipped onto the level chart which indicated the level s/he was on throughout the session. The children’s clips were moved up and down the level chart during intervention (described below).

Fig. 1.

Image of the level system used for both dyads

Measures, Interobserver Agreement, and Treatment Fidelity

The dependent variable was synchronous engagement (Vernon et al., 2012). Synchronous engagement was defined as times both children were simultaneously exhibiting favorable affect while engaging in the same activity. Engagement was defined as times both children were involved with the same activity (e.g., touching, manipulating). Favorable affect was defined as “visible and/or audible indications of happiness and enjoyment, including smiling, laughing, and physical affection (hugging and kissing)” (Vernon et al., 2012, p. 7). Synchronous engagement started anytime that both children were engaged in the same activity while displaying favorable affect and ended 3 s after one or both children were no longer engaged in the same activity or displaying favorable affect. Examples of synchronous engagement included, but were not limited to, if both children were pushing cars up or down a car ramp while both children were displaying favorable affect and if both children were engaging in a conversation with a tone indicating amusement while interacting with the same materials. Non-examples of synchronous engagement included, but were not limited to, if both children were pushing cars up and down a car ramp and one child was displaying favorable affect while the other child was displaying neutral affect and if both children were engaging in a conversation with a monotone while interacting with the same materials. Synchronous engagement was measured using a 10-s partial interval recording system (Powell, Martindale, & Kulp, 1975). That is, if synchronous engagement occurred at any point during the 10-s interval, in which interval was scored as SE. Partial interval recording was selected for synchronous engagement from observations of typically developing peers during 5 min of free play. These observations suggested that the peers did not engage in synchronous engagement continuously during the whole 5 min observation; therefore, whole interval recording systems may underestimate the duration and quality of the interaction with respect to SE.

A second observer recorded child responding during 33% of sessions across baseline, intervention, and dyads. An agreement occurred when both observers marked synchronous engagement as occurring during the same interval or marked synchronous engagement as not occurring during the same interval. A disagreement occurred when one observed marks synchronous engagement as occurring within an interval while the other observer did not. Interobserver agreement (IOA) was calculated by dividing the total number of agreements by the total number of agreements plus disagreements and multiplying by 100. IOA averaged 90% across conditions and ranged between 77 and 100%.

To ensure treatment fidelity, an independent observer recorded the interventionist’s implementation of the level system across 33% of sessions across baseline and intervention and dyads. Correct interventionist behavior during baseline consisted of (1) putting out five toys/toy sets, (2) instructing the children to go play, and (3) ending the session after 5 min. Correct interventionist behavior during intervention consisted of (1) putting out five toys/toy sets, (2) putting out the level system and treasure chest, (3) instructing the children to go play, (4) checking in after each minute, (5) ending the session after 5 min, and (6) providing the consequence based on where the child’s clip was at the end of each session. Treatment integrity was calculated by dividing the number of sessions during which the interventionist implemented all steps correctly over the total number of sessions and multiplying by 100. Treatment integrity across all baseline sessions was 100 and 100% across all intervention sessions.

Experimental Design

The effects of the level system on synchronous engagement of each dyad were evaluated using an ABAB reversal design (Baer, Wolf, & Risley, 1968). Experimental control within an ABAB reversal design is demonstrated if changes in the dependent variable are observed if, and only if, the independent variable is introduced and those effects are reversed when the independent variable is removed.

Baseline

During baseline, and prior to the children entering the room, the interventionist arranged the predetermined toys/toy sets for each session. When the children entered the room, the interventionist greeted the children and instructed them to “Find something to play with.” Following this instruction, the interventionist started a timer for 5 min. No programmed reinforcement occurred, and the interventionist did not interact with the children throughout the 5-min session. The interventionist would have, however, intervened if the children were going to cause harm to each other, which never occurred. After 5 min, the interventionist instructed the children that we were finished and the children were accompanied back to their regularly scheduled clinical session. It should be noted that neither the level system (described previously) nor the treasure chest were in the research room or visible to the participants during baseline sessions.

Intervention

The room was set up similar to baseline throughout the intervention. Toy/toy sets were arranged on the tables prior to the children entering the room. Additionally, the interventionist hung the level system on the wall with the toy treasure chest directly below. Once the children entered the room, the interventionist instructed the children to sit down in front of the level system (e.g., “Come have a seat over here”). During the first session with the level system, the interventionist then explained the system to the children by stating,

Today we are going to use the super friend chart [while pointing to the chart]. Each of you have a clip [while pointing to the clip]. If you end up on super friend, you can take something home from inside the treasure chest. If you end up on friend, you can play with something from the treasure chest for two minutes. If you end up on miss out on a fun activity, you don’t get to go to the treasure chest.

In an effort to ensure the children understood the system, the interventionist required the children to repeat the instructions with respect to the specific contingencies for each level (e.g., “If I end on Super Friend, I can take home a toy”). In sessions following the first intervention session, the interventionist would ask the participants to explain what happens at each level prior to stating them himself. After explaining the system, the interventionist instructed the children to go play and started a timer for 5 min.

The interventionist observed the children playing throughout the 5 min session. After each minute passed (i.e., a total of five times during each intervention session), the interventionist established attending (e.g. “Ok, let’s check in”) and moved each child up or down on the level system. Movement up was paired with general praise (e.g., “MacKenzie, I loved how you were playing with your friend! I can move you up!”), while movement down was paired with general informative feedback (e.g., “Will, you weren’t really playing with MacKenzie. I have to move you down.”). At no point during praise or feedback was affect specifically referenced (e.g., “I loved how you were both smiling at each other”). The interventionist used a flexible shaping strategy (Leaf et al., 2016b; Leaf et al., 2017) for moving the marker up, down, or leaving the marker unchanged. This strategy is similar to other studies documenting flexible approaches to behavior change such as in-the-moment reinforcer analysis (IMRA; e.g., Leaf et al., 2016a) and flexible prompt fading (FPF; Leaf, Leaf, Taubman, McEachin, & Delmolino, 2014).

If the behavior exhibited by a participant during the interval represented a general improvement, the marker would be moved up (i.e., the children’s markers moved independent of each other). Likewise, if the general quality of the behavior was below what was reasonable to expect of the child given a number of variables, the marker would be moved down. Some variables that were assessed and contributed to movement were how the child responded to movement (e.g., whether movement down resulted in the desired behavior change during the next interval), overall frequency and duration of the targeted behavior during the interval (e.g., during the interval did synchronous engagement occur more or less than the previous interval), and participant responding in current and previous sessions (e.g., during the session did synchronous engagement occur more or less than the previous session or sessions). Furthermore, engaging with the same item as the peer, responding to peer comments or requests, and/or following the peer to a new toy all could set the occasion for movement up through the levels. Ignoring comments or requests, engaging with a different item than the peer, and/or not following the peer to a new toy all could set the occasion for movement down through the levels.

Results

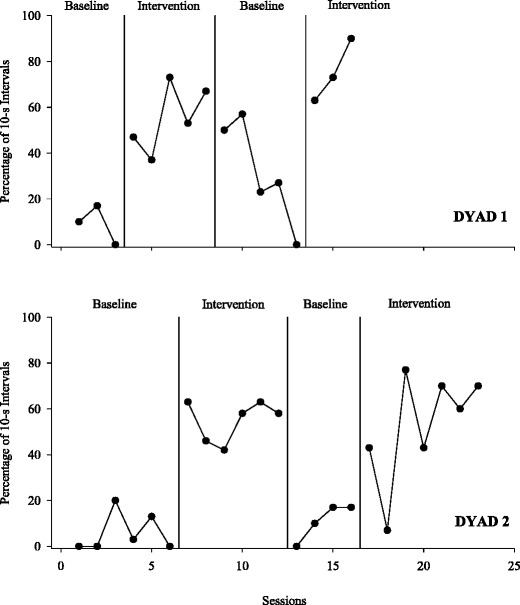

Figure 2 displays the results for both dyads. The top panel displays the results for dyad 1, Will and MacKenzie. During the first baseline condition, there was a low percentage (mean, 9%; range, 0 to 17%) of intervals in which synchronous engagement was observed. Following the introduction of the level system, there is an increase in the percentage of intervals in which synchronous engagement was observed (mean, 55%, range 37 to 73%). Returning to baseline conditions resulted in a large decrease in the percentage of intervals in which synchronous engagement was observed (mean, 31%; range, 0 to 57%) Reintroducing the level system resulted in a large increase in the percentage of intervals in which synchronous engagement was observed (mean, 75%; range, 63 to 90%). To further analyze the results from dyad 1, .the percentage of non-overlapping data (PND; Scruggs, Mastropieri, & Casto, 1987) was calculated. To calculate PND, the number of data points during the intervention phase above the highest data point in the baseline preceding that intervention phase was divided by the total number of data points during the intervention phase and multiplied by 100. The PND for the both phases of intervention for dyad 1 was 100% (i.e., highly effective).

Fig. 2.

The percentage of 10-s intervals in which SE was observed for each dyad

The bottom panel of Fig. 2 displays the results for dyad 2, Jim and Maggie. A similar pattern of responding was observed for dyad 2. During the first baseline condition, there were a low percentage (mean, 6%; range, 0 to 20%) of intervals in which synchronous engagement was observed. Following the introduction of the level system there is a large increase in the percentage of intervals in which synchronous engagement was observed (mean, 55%, range 42 to 63%). Returning to baseline conditions resulted in an immediate decrease in the percentage of intervals in which synchronous engagement was observed (mean, 11%; range, 0 to 17%). Reintroducing the level system resulted in a variable, but large increase in the percentage of intervals in which synchronous engagement was observed (mean, 52%; range, 7 to 77%). The PND for dyad 2 was 100% (i.e., highly effective) for the first phase of intervention and 86% (i.e., effective) for the second phase of intervention.

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that a level system can be effective in improving synchronous engagement with children diagnosed with ASD. The percentage of intervals in which synchronous engagement was observed in baseline conditions contrasted with intervention conditions when the level system was in place. For both dyads, changes from the first baseline to the first introduction of the level system were immediate. Returning to baseline conditions resulted in a decrease across sessions, and the reintroduction of the level system again resulted in an immediate increase in synchronous engagement. It should be noted that at no point was synchronous engagement observed in 100% of intervals for either dyad. Unlike measures of general engagement (e.g., two or more individuals interacting with the same activity), prolonged periods of synchronous engagement may not be appropriate or desired given that synchronous engagement is dependent upon mutual favorable affect. For example, if one child is pretending to be Darth Vader and one is pretending to be Obi-Wan Kenobi, it is likely that neither child will be displaying favorable affect, and, therefore, synchronous engagement would not be scored. Also, there are no empirical evaluations of typical levels of synchronous engagement with typically developing children. Future researchers evaluating synchronous engagement measures should collect ecological samples of typically developing children playing to compare and/or determine criterion levels of SE.

This study contributes to the limited literature examining the efficacy of the use of level systems in several ways. First, to the authors’ knowledge, this is the first experimental evaluation of a level system with individuals diagnosed with ASD. Although Leaf et al. (2017) used a level system similar to the one evaluated here, it was included as part of a treatment package; therefore, the contribution of the level system could not be determined. This study demonstrated the efficacy of the level system alone as opposed to its inclusion with other empirically based procedures. Second, to date, level systems have only been evaluated for ameliorating challenging behavior (e.g., Hagopian et al., 2002). This study, on the other hand, demonstrated that a level system can develop behavioral repertoires as opposed to eliminate challenging behavior. Third, ASD is marked by qualitative impairments with social skills (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Deficits in social and communication within ASD can manifest within peer play and, more specifically, a lack of mutually enjoyable engagement in peer play. The current study demonstrates an effective intervention to improve the appearance of mutually enjoyable engagement in age appropriate activities.

The limitations of this study can be evaluated from at least two different perspectives: research and practice. We will discuss the limitations from a research perspective first and hope that future researchers find the discussion fruitful and can address these limitations to continue to build on the limited research on SE, level systems, and flexible shaping. The first research limitation relates to the measurement of SE, which represents a complex interlocking of a variety of social behaviors. Common with most complex social behaviors, this creates difficulty with respect to operationalization. As a result, we provided definition by examples and non-examples, which may create replicability issues for future researchers. Perhaps the use of IOA can provide a potential avenue to ameliorate the measurement challenges for complex social behavior such as SE. While we achieved rather high agreement within this study, agreement only represents two observers. Future researchers may wish to include more independent observers when calculating IOA in addition to evaluating other means to operationalize complex social behaviors like SE.

On a related note, the use of a flexible shaping approach may also create replicability issues for future researchers. While flexible shaping may be common within practice, examining commonly implemented procedures like flexible shaping creates considerable difficulty for current and future research. The experience and competencies of the interventionist may be important variables to consider for future studies attempting to replicate the findings or train others on the use of flexible shaping. The interventionist in the current study had many years of experience providing ABA-based intervention for individuals diagnosed with ASD as well as academic training in behavior analysis. It is possible that similar results would not be achieved with an interventionist with less experience and training. Future researchers should examine the experience, knowledge, and measurable competencies required to effectively implement flexible shaping. Furthermore, future researchers may wish to examine if training in shaping specifically is sufficient or if more comprehensive training is necessary (e.g., Weinkauf, Zeug, Anderson, & Ala’i-Rosales, 2010).

Other limitations of potential interest to future researchers include the use of only two dyads, the treasure chest and level system were only present during intervention (i.e., not in baseline), and treatment fidelity not including fidelity regarding the contingencies on level movement behaviors or level change decisions. Future researchers may wish to address these limitations through including multiple dyads with more diverse participants, including the visibility of the treasure chest and level system across conditions, and including other treatment fidelity measures evaluating the flexible shaping approach.

While the use of flexible shaping and synchronous engagement create replicability challenges for researchers, they may not be limitations for clinicians who could use this intervention. There are, however, limitations of the intervention (as evaluated in this study) that may be of interest to clinicians. First, while the current study demonstrates experimental control, this may not be desirable for clinicians. Moreover, removal of the level system resulted in decreases in the percentage of intervals in which synchronous engagement was observed. While this was important to demonstrate with respect to experimental control, this may not map onto clinical practice, especially in the social area, in which it is desirable for the effects to continue after the removal of the level system. Therefore, clinicians should be aware of this potential within practice, and future researchers may wish to evaluate the effective fading techniques of level systems across a variety of contexts while maintaining the effects of its use. Second, the participants within each dyad had fairly sophisticated vocal/verbal repertoires and minimal challenging behavior. Until future researchers are able to evaluate this intervention with more diverse children, clinicians should be cautious about using this intervention with children greatly differing from those who participated in this study. Finally, this study only evaluated the use of a three-tiered level system across a relatively short period of time (i.e., 5 min). Within practice, however, such short durations may not be feasible, and this study, by itself, does not permit evaluation of the intervention with more tiers (i.e., levels) and increased durations. Therefore, practitioners should be cautious about the use of the intervention across longer period of times until future researchers can evaluate the use of level systems over longer periods, including up to several hours, and examine the utility of level systems with more differentiation between levels.

While this study did not go without its limitations, its merits should not be discounted. This study represents an empirical demonstration of a rather simple behavioral system to improve a complex social skill with individuals who, by definition, have deficits in social skills. Level systems could be effective for a wide variety of behaviors and this study provides further empirical evidence that level systems are not only effective at improving skills, but also effective with skills commonly associated with an autism diagnosis. This study also represents an evaluation of a common clinical practice, flexible shaping. Flexible approaches to ASD intervention are garnering more attention within the literature (e.g., Leaf et al., 2016a; Leaf et al., 2016b; Leaf et al., 2017; Leaf et al., 2014). However, the research on shaping within the applied setting remains limited, and the majority of the literature on flexible approaches is originating from the same research group. It is our hope that this study, in combination with the growing literature on flexible approaches to ASD intervention, motivates other research groups to build on the external validity of structured, yet flexible approaches to ASD intervention.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th Ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

- Baer DM, Wolf MM, Risley TR. Some current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1968;1(1):91–97. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1968.1-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer AM, Shea TM, Keppler R. Levels systems: a framework for the individualization of behavior management. Behavioral Disorders. 1986;12(1):28–35. doi: 10.1177/019874298601200101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JO, Heron TE, Heward WL. Contingency contracting, token economy, and group contingencies. In Applied behavior analysis. 2. Upper Saddle: Pearson; 2007. pp. 550–574. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell DT, Smith SW, Brownell MT. Teacher perceptions of level system effectiveness on the behavior of students with emotional or behavioral disorders. The Journal of Special Education. 1998;32(2):89–98. doi: 10.1177/002246699803200203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez ML, Taylor T, Borrero CSW, Sangkavasi E. An individualized levels system to increase independent mealtime behavior in children with food refusal. Behavioral Interventions. 2013;28(2):143–157. doi: 10.1002/bin.1358. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hagopian LP, Rush KS, Richman DM, Kurtz PF, Contrucci SA, Crosland K. The development and application of individualized levels systems for the treatment of severe problem behavior. Behavior Therapy. 2002;33(1):65–86. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(02)80006-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Bootzin RR. The token economy: an evaluative review. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1972;5(3):343–372. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1972.5-343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaf, J. B., Leaf, R., Leaf, J. A., Alcalay, A., Ravid, D., Dale, S., … & Oppenheim-Leaf, M. (2016a). Comparing paired-stimulus preference assessments with in-the-moment reinforcer analysis on skill acquisition: a preliminary investigation. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 1–11.

- Leaf, J. B., Leaf, R., McEachin, J., Taubman, M., Ala’i-Rosales, S., Ross, R. K., … & Weiss, M. J. (2016b). Applied behavior analysis is a science and, therefore, progressive. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(2), 720–731. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Leaf, J. B., Leaf, J. A., Milne, C., Taubman, M., Oppenheim-Leaf, M., Torres, N., … & Yoder, P. (2017). An evaluation of a behaviorally based social skills group for individuals diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(2), 243–259. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Leaf JB, Leaf R, Taubman M, McEachin J, Delmolino L. Comparison of flexible prompt fading to error correction for children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities. 2014;26(2):203–224. doi: 10.1007/s10882-013-9354-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr WK, Martin A, Olson JN, Pumariega AJ, Branca N. Beyond point and level systems: moving toward child-centered programming. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2009;79(1):8–18. doi: 10.1037/a0015375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell J, Martindale A, Kulp S. An evaluation of time-sample measures of behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1975;8(4):463–469. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1975.8-463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scruggs TE, Mastropieri MA, Casto G. The quantitative synthesis of single-subject research: methodology and validation. Remedial and Special Education. 1987;8:24–33. doi: 10.1177/074193258700800206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SW, Farrell DT. Level system use in special education: classroom intervention with prima facie appeal. Behavioral Disorders. 1993;18(4):251–264. doi: 10.1177/019874299301800408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vernon TW, Koegel RL, Dauterman H, Stolen K. An early engagement intervention for young children with autism and their parents. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2012;42(12):2702–2717. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1535-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinkauf S, Zeug N, Anderson C, Ala’i-Rosales S. Evaluating the effectiveness of a comprehensive staff training package for behavioral interventions for children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2010;5:864–871. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2010.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]