Abstract

Social communication skills such as joint attention (JA), requesting, and social referencing (SR) are deficits in children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Shifting gaze is a common response across these skills. In many studies, children respond variably to intervention, resulting in modifications to planned intervention procedures. In this study, we attempted to replicate the procedures of Krstovska-Guerrero and Jones (Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities 28; 289–316, 2016) and Muzammal and Jones (Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities 29; 203–221, 2017) to teach JA, requesting, and SR. In general, intervention procedures consisting of prompting and reinforcement were effective in teaching requesting, SR, and JA skills to children with ASD. However, not all children acquired each skill, and all children required individualized procedures to acquire some skills. We report the process of deciding how to modify intervention and discuss considerations for practitioners when planning intervention that may improve children’s performance.

Keywords: Autism, Communication, Eye gaze, Joint attention, Requesting, Social referencing

Children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) show deficits in early social communication skills such as joint attention, requesting, and social referencing, all of which emerge in typically developing infants within the first year of life. Joint attention (JA) is one of the earliest nonvocal social communication skills (Beuker, Rommelse, Donders, & Buitelaar, 2013). JA is typically defined as involving coordinating attention between a social partner and an event in the environment, for the purely social consequence of sharing an experience. For example, a mother turns her head and shifts her gaze toward an interesting new photo on the wall. Her child then responds by following his mother’s gaze, turning his head toward the photo, and then looking back at his mother’s eyes. Later an airplane passes overhead outside; the child points and looks up at the airplane and looks back at his mother’s eyes. His mother responds by looking up, smiling, and commenting, “Wow, it’s a big airplane!” These examples illustrate two types of JA. The former involves a child following his mother’s gaze to respond to her joint attention bid (RJA) to look at the new photo. In behavioral terms, the mother’s head turn and eye gaze are antecedent stimuli in the presence of which looking in that direction usually leads to reinforcing consequences in the form of visual stimulation from the event (e.g., photo on the wall) and/or social praise from mom (Dube, MacDonald, Mansfield, Holcomb, & Ahearn, 2004; Holth, 2005; Isaksen & Holth, 2009). The child shifting his gaze from the event back to mom may lead to further reinforcement in the form of social interaction. In the latter example, the child shifts his gaze to initiate a joint attention bid (IJA) to direct his mother’s attention toward the airplane. The event in the environment (e.g., the airplane passing overhead) and the presence of his mother nearby are antecedent stimuli that signal the availability of attention from mom contingent on shifting his gaze from the event to his mother’s eyes (Dube et al., 2004; Holth, 2005; Isaksen & Holth, 2009).

JA is considered a component of social referencing (SR; Holth, 2005). Infants typically engage in SR in the presence of a novel or ambiguous event in the environment, which serves as an antecedent stimulus to shift gaze to an adult’s eyes, similar to a JA interaction. The adult may then provide a facial cue such as a smile or frown that serves as an antecedent for the child to engage in a behavioral regulation response (i.e., approach or avoid the event). The facial cue provided by the adult serves as a reinforcer for the gaze shift response and an antecedent stimulus for the behavioral regulation response (DeQuinzio, Poulson, Townsend, & Taylor, 2016; Holth, 2005; Klinnert, Emde, Butterfield, & Campos, 1986; Pelaez, Virues-Ortega, & Gewirtz, 2012).

Young children also shift gaze to request access to tangible items or events from a person in their environment (Mundy, 1995). In behavior-analytic terms, this is manding. Manding typically involves a motivating operation (e.g., deprivation of cookies) and, contingent on a response (e.g., child shifts gaze from cookies to mom and says, “I want cookies.”), the listener provides the reinforcer (e.g., cookies) that is related to that motivating operation (Skinner, 1957). When very young children request or mand, they gaze from the desired item to their caregivers’ eyes, the same topography of behavior observed in JA and SR. An infant may look at an item his or her parent is offering and then look at the parent’s eyes, responding to the parent’s request (RR), or the infant may initiate a request (IR) by looking at a preferred item that is out of reach and then back at his or her parent’s eyes. The item in the palm of the parent’s hand and the item that is out of reach are antecedent stimuli in the presence of which shifting gaze leads to the parent providing the preferred item.

Shifting gaze, in which the child moves his or her gaze from an object to his or her caregiver’s eyes, is a common topography across JA, SR, and requesting. Although it is the same response, the consequences of shifting gaze are different. The consequences for engaging in JA are purely social, whereas SR and requesting are followed by access to information and preferred items.

Challenges in early social communication skills including JA, SR, and eye contact are considered to be discriminative characteristics of infants and young children with and at risk of being diagnosed with ASD (Neimy, Pelaez, Carrow, Monlux, & Tarbox, 2017). Younger siblings of a child diagnosed with ASD who later go on to receive a diagnosis of ASD show deficits in many of these early social communication skills, including the response topographies of eye contact, disengagement of visual attention, and shifting gaze (Zwaigenbaum et al., 2005). At-risk siblings also show deficits in SR (Cornew, Dobkins, Akshoomoff, McCleery, & Carver, 2012), as well as JA and requesting (e.g., Landa, Holman, & Garrett-Mayer, 2007; Rozga et al., 2011). Deficits in initiating interactions, such as IJA, when children point, show, or use eye gaze to communicate, have been identified as discriminative characteristics of children with ASD (Mundy, Sigman, Ungerer, & Sherman, 1986; Stone, Ousley, Yoder, Hogan, & Hepburn, 1997). These skills may be pivotal such that, when acquired, they are associated with broad changes in other untrained areas of social communication development. JA acquisition is related to gains in other untrained social communication behaviors such as smiling (e.g., Krstovska-Guerrero & Jones, 2016; Whalen, Schreibman, & Ingersoll, 2006), vocalizations (Jones, Carr, & Feeley, 2006; Whalen et al., 2006), imitation, and play skills (Whalen et al., 2006). Teaching children with ASD to mand for reinforcing items is associated with collateral changes in social initiations, increases in other modes of communication, and even JA (Charlop-Christy, Carpenter, Le, LeBlanc, & Kellet, 2002).

A large literature suggests that there are documented effective behavioral intervention procedures to improve early social communication skills in young children with ASD (e.g., Hansen, Carnett, & Tullis, 2018; Murza, Schwartz, Hahs-Vaughn, & Nye, 2016; White et al., 2011) and even those at risk (Neimy et al., 2017). In many of these studies, the authors use the same intervention procedures for all participants. In two recent studies, Krstovska-Guerrero and Jones (2016) and Muzammal and Jones (2017) successfully taught young children with ASD early social communication skills, specifically, gaze shift to both request and engage in JA. Intervention procedures consisted of most-to-least prompting with a time delay, as well as access to a preferred item as reinforcement, which was eventually faded so only social consequences were provided for JA. Prompting consisted of a full prompt in which the interventionist moved her hand or an object to her eyes, a partial prompt in which the interventionist moved her hand or an object halfway to her eyes, and a time delay in which the interventionist waited 2 s (Krstovska-Guerrero & Jones, 2016) or 4 s (Muzammal & Jones, 2017) for the child to respond before providing any prompt. In addition to the same procedures resulting in increases in JA and requesting, in both studies children showed some generalization across social communication skills. In Krstovska-Guerrero and Jones (2016), children showed variable gains in generalization to multiple untrained social communicative skills. In Muzammal and Jones (2017), two children generalized to IJA, whereas the other did not until intervention was introduced.

Although some research suggests that the same intervention procedures may be effective across children, in other studies, at least some participants do not respond to the planned intervention procedures and are subsequently removed from intervention (e.g., Ferraioli & Harris, 2011; Whalen & Schreibman, 2003). Alternately, when children do not respond to planned intervention procedures, individualized procedures may improve performance. Rudy, Betz, Malone, Henry, and Chong (2014) used video modeling to teach IJA to children with ASD. Video modeling alone worked for two of the three children. One child required video modeling and a prompt at the child’s chin to shift gaze. It is not clear why the interventionist chose to use a prompt at the child’s chin or if the interventionist tried another prompt first. In Taylor and Hoch (2008), the planned intervention procedure was a least-to-most prompting procedure with gestural, physical, verbal, and echoic prompts to teach RJA and most-to-least prompting with physical, gestural, and echoic prompts and a prompt delay to teach IJA to children with ASD. The interventionist also planned to only provide comments and social interaction contingent on JA. These intervention procedures were effective for two of the three children. One child did not respond to the prompt delay during IJA intervention. Based on the child’s learning history, the interventionist introduced an individualized textual checklist prompt, as well as access to a preferred item contingent on IJA, to teach this child IJA. In another study, interventionists conducted a preassessment to help guide the choice of prompting procedures. The preassessment in Kryzak and Jones (2015) involved the interventionist saying the child’s name or the word “look” or tracing the child’s gaze with a stimulus in order to determine which antecedent evoked the child’s eye contact. For one of three children, the prompts that were selected based on the preassessment were not effective in evoking eye contact to engage in IJA while the child was engaging in circumscribed interest items. The interventionist then modified prompt procedures multiple times, but each time performance declined when prompts were faded to a time delay. The interventionist eventually changed the materials from circumscribed interest materials to preferred items, resulting in improvements in IJA. Thus, across JA intervention studies, changes in materials, prompts, and consequences may be considered to individualize intervention when children do not respond to planned procedures.

As in Taylor and Hoch (2008) and Kryzak and Jones (2015), interventionists sometimes also change prompting procedures during intervention for requesting with children with ASD. In a study of teaching multistep requests with a speech-generating device, Waddington et al. (2014) modified their planned procedures in two ways. For one of the three children, individualized intervention included changing the format of the display icons on the communication device. Another child resisted physical prompts. For this child, the interventionist switched from physical to verbal and gestural prompts and provided access to a preferred edible after each trial. Ganz, Lashley, and Rispoli (2010) not only changed prompts but also increased the intensity of intervention to teach two young children with autism to request. The interventionist first implemented a verbal modeling procedure with a time delay. When the children did not make gains in spontaneous requesting, the interventionist implemented a picture exchange communication systems (PECS) protocol. When the children did not make progress with the first phase of PECS, the interventionists increased the intensity of intervention by physically prompting the response during massed opportunities of the first phase of PECS. Even with these additional opportunities, both children did not consistently request and intervention was terminated. These studies highlight the need for more literature examining ways to troubleshoot intervention procedures for children who do not respond to intervention.

Less literature has examined intervention procedures to improve SR in children with ASD. Behavior-analytic procedures, however, are effective in increasing SR in typically developing infants (Pelaez, Virues-Ortega, Field, Amir-Kiaei, & Schnerch, 2013; Pelaez et al., 2012). As with JA and requesting, in the one study that taught SR to children with ASD, children showed variable responding. Brim, Townsend, DeQuinzio, and Poulson (2009) taught four children with ASD to engage in SR in the context of ambiguous academic tasks (e.g., a handwriting task with a jumbo marker). The interventionist used visual and verbal prompting to teach children to observe the interventionist’s face and graduated guidance to teach children to complete the task in the presence of a happy face and terminate the task in the presence of a frowning face. Three of the children acquired SR within a similar number of sessions; one child required many more sessions to acquire SR, potentially due to his learning history. The interventionist also examined if children demonstrated discrimination of the observing response by interspersing ambiguous and standard academic tasks. Although one child demonstrated this discrimination response, two children required further intervention to learn to perform the observing response only in the presence of ambiguous and not standard tasks. Similar to studies addressing JA and requesting skills in children with ASD, the results of this study suggests that individuals with ASD are likely to respond differently to SR intervention procedures and may require individualized intervention procedures.

Across studies of interventions to improve early social communication skills in children with ASD, there are many modifications to planned procedures when children do not respond to the planned intervention. The decision-making process for modifying materials, prompts, or consequences often remains unclear. In many cases, interventionists rely on information about the child’s learning history. Understanding factors to consider and what alternative procedures are in fact considered may help practitioners effectively intervene with children with ASD who show a range of characteristics. In this study, we attempted to replicate the procedures of Krstovska-Guerrero and Jones (2016) and Muzammal and Jones (2017) to teach JA, requesting, and SR and examine generalization across social communication skills. We chose to do so because of their consistent findings in which all children responded to JA and requesting intervention procedures. In attempting to replicate procedures that were successful without modification in two previous studies, we found that children responded very differently. As a result, we explored ways to individualize intervention to enhance learning for each child and skill. In this article we report the results of planned intervention procedures along with a detailed discussion of our process for making modifications.

Method

Participants

Children were included if parents reported a diagnosis of ASD from a licensed psychologist, pediatrician, or neurologist not affiliated with this research and provided informed consent. The institutional review board of Queens College, City University of New York, approved this study, and parents provided informed consent. Children were excluded if they did not demonstrate basic attending skills such as sitting upright and orienting toward the interventionist when the interventionist waved her hands or clapped to attempt to gain the child’s attention. Children were also excluded if they did not visually track moving objects or orient toward objects moving or lighting up/making noise. The interventionist presented five opportunities to screen for these behaviors; children responded correctly on 80% or more of the opportunities for each behavior. In addition, all children demonstrated the prerequisite skill of looking at a toy to which the interventionist pointed. One child was initially included in this study but then excluded when interfering problem behaviors emerged during preference assessments (prior to beginning intervention) and reevaluation revealed that he no longer met the prerequisite criteria. One child began intervention for requesting, but scheduling conflicts with therapies prohibited continuation.

Parents completed a survey of descriptive information about their children. A trained graduate student who did not conduct intervention with the child administered the Mullen Scales of Early Learning (MSEL; Mullen, 1995) to describe language, perceptual, and motor development; the Childhood Autism Rating Scale™, Second Edition (CARS™-2; Schopler, Van Bourgondien, Wellman, & Love, 2010), to describe symptomology; the Preschool Language Scale™, Fifth Edition (PLS™-5; Zimmerman, Steiner, & Pond, 2011), to describe auditory comprehension and expressive communication; and Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, Second Edition (Vineland™-II; Sparrow, Cicchetti, & Balla, 2005), to describe communication, daily living skills, socialization, and motor skills.

All three children were 3- to 4-year-old boys diagnosed with ASD according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), and receiving early intervention services and school-based intervention each week. Table 1 describes each child and his performance on the various assessments.

Table 1.

Descriptive information and performance on standardized assessments

| Trevor | Edward | Neil | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptive information | |||

| Age in months | 50 | 44 | 46 |

| Early intervention received before study in months | 2 | 24 | 34 |

| Early intervention services hr/week | 10–20 | 14 | 4 |

| Speech and language therapy hr/week | 6 | No response | No response |

| School-based interventions hr/week | More than 10 | More than 10 | 4–6 |

| Occupational therapy hr/week | None | No response | None |

| Mullen (descriptive category) | |||

| Visual reception |

Very low (1st percentile) |

Very low (1st percentile) |

Very low (1st percentile) |

| Fine motor |

Very low (1st percentile) |

Very low (1st percentile) |

Very low (1st percentile) |

| Receptive language |

Very low (1st percentile) |

Very low (1st percentile) |

Very low (1st percentile) |

| Expressive language |

Very low (1st percentile) |

Very low (1st percentile) |

Very low (1st percentile) |

| PLS™-5 (age equivalent) | |||

| Auditory comprehension |

1 year 1 month (1st percentile) |

2 years (1st percentile) |

9 months (1st percentile) |

| Expressive communication |

11 months (1st percentile) |

1 year 5 months (1st percentile) |

5 months (1st percentile) |

| Total language score |

11 months (1st percentile) |

1 year 8 months (1st percentile) |

7 months (1st percentile) |

| CARS™-2 (severity group) | |||

|

Mild-to-moderate symptoms of ASD (42nd percentile) |

Minimal-to-no symptoms of ASD (8th percentile) |

Severe symptoms of ASD (50th percentile) |

|

| Vineland™-II domains (adaptive level) | |||

| Communication |

Adequate (50th percentile) |

Low (2nd percentile) |

Low (<1 percentile) |

| Daily living skills |

Moderately low (10th percentile) |

Moderately low (4th percentile) |

Low (1st percentile) |

| Socialization |

Adequate (30th percentile) |

N/A |

Low (<1 percentile) |

| Motor skills |

Adequate (50th percentile) |

N/A |

Low (<1 percentile) |

| Diagnosis | ASD | ASD | ASD |

N/A indicates that the score could not be reported because too many items were left blank

Materials

A video camera was used to record all sessions. All baseline and intervention data were collected on data sheets.

Each child’s parent identified preferred types of toys and any toys to which the child might react negatively. Based on the parents’ initial reports, the interventionist selected a total of 45 toys for paired stimulus preference assessments. Of the 45 toys, 15 were stuffed animals and figures (to be used during RJA); 15 were activities with multiple pieces (to be used during requesting); and 15 were toys that activate with light, motion, and/or sound (to be used during IJA). The interventionist conducted preference assessments in groups of five toys that all had similar characteristics (e.g., a group of five toys with multiple pieces consisted of one preference assessment). In total, the interventionist conducted three preference assessments each consisting of five activities with multiple pieces; three preference assessments each consisting of five toys that activate with light, noise, or motion; and three preference assessments each consisting of five figures or stuffed animals. The three most preferred toys from each preference assessment were chosen for intervention resulting in nine stuffed animals/figures, nine multiple-piece activities, and nine toys that activate. These were supplemented with similar toys as those identified through the preference assessments in an effort to maintain children’s interest and motivation during instruction (e.g., if the preference assessment identified a red car as preferred, the interventionist may have also used a different color, but otherwise similar, car). During requesting, the interventionist used the nine toys with multiple pieces, identified in the preference assessments, and the same toy was provided to the child as part of the consequence for engaging in requesting.

During JA, toys identified as preferred from the preference assessments were used to set up the JA interaction (i.e., the nine stuffed animals/figures and the nine toys that activate were used to set up RJA and IJA opportunities). Following a correct JA response, the interventionist gave the child another toy as a reinforcer. The interventionist identified toys to use as reinforcers for JA based on parent report of child preferences and brief preference assessments throughout intervention. During SR, a cardboard box was used to set up the SR interaction. The object that was placed in the box that the child later received was also one of the toys identified through ongoing brief preference assessments.

Setting and Interventionist

Sessions took place in the child’s home either at a table or on the floor with the child seated in a small booster seat. The first author implemented intervention; she had over three years of experience teaching children with developmental disabilities using applied behavior-analytic procedures and was enrolled in a psychology doctoral program with an emphasis in behavior analysis at the Graduate Center, City University of New York. For Neil, a trained graduate student in the master’s in applied behavior analysis program at Queens College, City University of New York, also implemented intervention.

Dependent Variables

Children were taught to shift gaze for requesting, JA, and SR. The term “requesting” is used here because a motivating operation was not manipulated during requesting. Gaze shift (GS) for RR, RJA, and IJA was defined as the child directing his gaze directly from a toy/object to the interventionist’s eyes within 4 s of looking at the toy. During SR, the child shifted gaze directly from the box to the interventionist’s eyes within 5 s of the presentation of the box and then engaged in the following behavioral response: He either touched/opened the box within 5 s of GS on positive affect opportunities or sat with his hands 30 cm away from the box within 5 s of GS on negative affect opportunities. During negative affect opportunities, the child could have engaged in other responses (e.g., hands folded) as long as his hands were 30 cm away from the box.

The interventionist recorded the percentage of opportunities with a correct GS response for requesting and JA. For SR, the interventionist recorded the percentage of opportunities in which the child engaged in the GS and correct behavioral responses. During full- and partial-prompt conditions (described shortly), percentage of correct responses include prompted and, if they occurred, independent responses. During the time delay condition (described shortly), percentage of correct responses included only independent responses (i.e., those that occurred before the end of the time delay and the interventionist’s prompt).

Experimental Design

A nonconcurrent multiple-baseline probe design across participants was used to evaluate the effectiveness of intervention involving prompting and reinforcement on RR, SR, RJA, and IJA (Watson & Workman, 1981). The interventionist randomly assigned each child to receive 5, 10, or 15 baseline sessions for each of RR, SR, RJA, and IJA skills. The interventionist began by teaching RR, and performance of SR, RJA, and IJA was probed during the time delay condition for RR. After mastery of RR, intervention for skills that did not reach mastery criteria of 80% were introduced. For Edward and Neil, intervention was introduced in this order: SR, RJA, and IJA; for Trevor, intervention proceeded with SR and then IJA. Performance for remaining skills was examined during the time delay of each skill currently in intervention.

Procedure

Baseline

Following preassessments, the interventionist conducted baseline sessions and began intervention. Table 2 describes opportunities for each skill and prompting and reinforcement procedures in detail.

Table 2.

Intervention procedures for all children

| Opportunity | Prompting | Consequences | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FP | PP | TD | |||

| RR | While child played with a toy, interventionist said the child’s name and offered a piece of an activity (e.g., puzzle piece) in the palm of her hand out of the child’s reach. | Interventionist moved the offered toy slowly to her eyes. | Interventionist moved the offered toy halfway to her eyes. | Interventionist waited 4 s for the child to GS. | Interventionist provided social praise and access to the piece in her hand. |

| SR | Interventionist placed a box in front of and 35 cm away from the child. | Interventionist moved her index finger from the box to her eyes. | Interventionist moved her index finger halfway to her eyes. | Interventionist waited 5 s for the child to GS and then 5 s for the child to engage in the behavioral response. | For both positive and negative affect opportunities, interventionist provided the same preferred item that was in the box during positive affect opportunities, as well as social praise. |

| Positive affect opportunities: A toy had been placed inside the box and the interventionist smiled/nodded. | Interventionist prompted the child’s hands to open the box. | Interventionist prompted the child at the wrist to open the box. | |||

| Negative affect opportunities: Nothing was inside the box and the interventionist frowned/shook her head. | Interventionist prompted the child’s hands 30 cm away from the box. | Interventionist prompted the child’s wrist 30 cm away from the box. | |||

| RJA | Interventionist placed a toy on the left or right side of the child within 50 cm, gained the child’s attention by moving her hand or face in the child’s line of vision, and turned her head toward the toy. | Interventionist held her index finger in front of her face and moved her finger toward the toy as she turned her head. After the child looked at the toy for 1 s, the interventionist moved her index finger from the toy back to her eyes. | Interventionist moved her index finger halfway to the toy. After the child looked at the toy for 1 s, she moved her finger halfway between the toy and her eyes. | Interventionist waited 4 s for the child to look at the toy and then GS. | The child did not directly gain access to the JA toy, but the interventionist commented on the toy and physically engaged the child with the toy (e.g., running a toy car along the child’s arm). |

| IJA | Interventionist placed a toy that activates on the left or right side of the child within 50 cm and activated the toy. | When the toy stopped moving or lighting up, the interventionist used her finger to trace a path from the toy to her eyes. | The interventionist traced half of the pathway between the toy and her eyes | The interventionist activated the toy and waited 4 s after the toy stopped moving for the child to GS. | The child did not directly gain access to the toy, but the interventionist commented on the toy and physically engaged the child with the toy. |

During baseline, the interventionist sat across from the child and presented opportunities for each skill but did not prompt or reinforce responses. Because the natural consequence for gaze shift in RR is receipt of one of the pieces of the toy activity, the interventionist began RR sessions with a preference assessment during which the interventionist presented the child with two activities from the preferred activities assigned to requesting and asked the child to choose one. The first activity chosen was used to begin the session. During the session, if the child no longer looked at the activity and/or displayed negative affect toward the activity (e.g., frowning, whining, or crying), another preference assessment was conducted with two new activities to determine the next activity. The interventionist waited 4 s during RR, RJA, and IJA and 5 s during SR for the child to shift gaze. She provided only natural consequences if the child shifted his gaze (e.g., smiling and commenting on the toy during a JA opportunity). The interventionist also provided a reinforcer after approximately the first, third, and fifth opportunities contingent on sitting and attending behaviors. A new opportunity began after about 5 s lapsed since the end of the previous opportunity or the end of access to a reinforcer and the interventionist said something like, “Let’s keep going.” For RR, RJA, and IJA, baseline sessions consisted of five opportunities. For SR, sessions consisted of three positive affect and three negative affect opportunities, randomly sequenced.

Intervention

Intervention (described in Table 2) was conducted 1–3 sessions per day, 1–3 days per week depending on the child’s availability and lasted for approximately 10–15 min per session with a 3–5 min break between sessions, during which the child and interventionist engaged in free play. All intervention sessions consisted of 10 opportunities. Sessions began as in baseline. The interventionist introduced and faded prompts from a full prompt (FP) to a partial prompt (PP) and to a time delay (TD). During PP and TD, incorrect or no responding resulted in the use of the last successful prompt to ensure the child practiced the correct response every opportunity. The TD for GS for requesting and JA was 4 s for all participants, similar to previous research in which children with ASD were taught to GS to engage in JA (Jones, 2009; Krstovska-Guerrero & Jones, 2013). The TD for GS during SR was 5 s, based on previous research in which children with autism were taught to GS during an ambiguous task (e.g., Brim et al., 2009). During the time delay condition, only independent responses (i.e., those that occurred before the end of the time delay and the interventionist’s prompt) were considered correct. Reinforcement consisted of social praise (e.g., “Good looking! It is a car!”), as well as natural consequences consistent with each skill. For JA, tangible reinforcement was initially provided. For Neil and Trevor, it was not necessary to fade tangible reinforcement because they demonstrated the skill during probe sessions where tangible consequences were not provided. For Edward, this tangible reinforcement was faded out, so the interventionist only provided social consequences. To fade tangible reinforcers during RJA, when Edward performed at 80% correct responding for one session in the PP condition, the interventionist provided access to the preferred item in which every two responses (FR2) resulted in a preferred toy. The interventionist continued to provide natural social consequences and praise following every correct response (FR1) throughout intervention. When Edward performed at 80% correct for another session with a PP on an FR2, the interventionist introduced access to a preferred item on an FR5. From Sessions 45 through 47, performance declined during TD with an FR5. At Session 48, a PP with an FR1 schedule was reintroduced. Prompts were faded from a PP to TD with an FR1 schedule until Edward reached mastery. Only then, at Session 52, did the interventionist begin an FR2 again. Reinforcement was further faded to an FR5 during Session 53, and an FR10 during Session 55, contingent on Edward performing above 80%. Prompt fading and mastery criterion was 80% or above correct responding across two consecutive sessions across 2 days.

Three types of changes were made to individualize intervention procedures (described in detail in Table 3): reintroduction of more intrusive prompts, modification of prompts, and changes in antecedent opportunities. Prompts were reintroduced if the child’s responding decreased or remained below mastery level for two or more sessions. Factors such as environmental and child conditions were considered when reintroducing a more intrusive prompt (e.g., if performance was low, but the child’s mother reported he did not feel well, the interventionist conducted another session at the current prompt level on the next visit). If the interventionist introduced a more intrusive prompt two or more times and the child’s performance still remained low when fading those prompts, or if the child stopped responding to error-correction procedures, the interventionist modified the prompting procedure. For example, for Edward during IJA intervention around Session 69, performance declined and Edward was not responding to error-correction procedures. At this point the interventionist modified the prompt (i.e., she moved her hand while holding a toy visible in her palm). If the interventionist reintroduced a prompt and modified the prompt multiple times, but performance remained low or variable, she modified the antecedent opportunity. This modification was only made for Neil when teaching RJA.

Table 3.

Individualized intervention procedures

| Reintroduction of a previous prompt | Modification of a prompt | Modification of the antecedent opportunity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | Trevor | Reintroduced FP (12) | N/A | N/A |

| Edward | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Neil | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| SR | Trevor | Reintroduced PP (40) |

FP/FP: Interventionist provided an FP for both the GS and behavioral response (44). PP/FP: Interventionist provided a PP for GS and an FP for behavioral response (47). TD/FP: Interventionist waited 5 s (TD) for the GS and provided an FP for the behavioral response (49). TD/PP: Interventionist waited 5 s for the GS and provided a PP for the behavioral response (52). |

N/A |

| Edward | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Neil | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| RJA | Trevor | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Edward | Reintroduced PP (48) | N/A | N/A | |

| Neil |

Reintroduced FP (64) Reintroduced PP (74) |

PP2: Interventionist moved index finger a quarter of the way to the toy and then a quarter of the way back to her eyes (80). PP3: Interventionist kept her index finger in front of her face but did not move her finger (82). |

RJA with a point: Interventionist pointed toward the toy in addition to turning her head (89). | |

| IJA | Trevor | Reintroduced PP (64) | N/A | N/A |

| Edward | Reintroduced PP2 (77) | PP2: Same procedure as original PP but the interventionist held a preferred toy visible in her palm (70). | N/A | |

| Neil | N/A | N/A | N/A |

The number in parentheses indicates the session in which the interventionist changed the prompt or antecedent

Generalization

Generalization probes were conducted during baseline and within 1 week of mastery of each of RR, SR, RJA, and IJA. Generalization probes involved the same toys as during baseline and intervention, but no prompting or error-correction feedback. The interventionist provided only natural consequences for JA (i.e., commenting on the toy and smiling and nodding), requesting (i.e., giving the child the toy), and SR (i.e., access to the toy inside the box during smiling and nodding opportunities).

The interventionist examined generalization of GS to a broad array of social communication skills. The interventionist presented RR opportunities in which she only said the child’s name but did not offer the toy (GS: RR [name]), offered the toy but did not say the child’s name (GS: RR [offer]), and extended her palm open and upright as though asking for the child to give her the toy (GS: RR [give me]). The interventionist also presented IR opportunities in which she placed one of the child’s preferred items near the child but out of his reach (GS: IR). On RJA generalization opportunities, the interventionist turned her head toward an item, pointed toward the item, and commented about the item (e.g., “What a fun toy!”; GS: RJA [head turn, point, and comment]). On IJA generalization opportunities, the interventionist provided the child access to a toy that lit up or made noise for 12 s of play to examine whether the child shifted gaze in order to share the experience of the toy lighting up or making noise with the interventionist (GS: IJA [toy in hand]).

Generalization of all skills was examined with each child’s mother. The interventionist instructed each child’s mother to present the opportunity, not provide prompts, and only provide natural consequences if the child engaged in the behavior. The interventionist then modeled an opportunity and observed each mother while she was providing opportunities to her child. The interventionist provided corrective feedback when needed, but treatment integrity was not recorded. Maintenance of skills with both mom and the interventionist was examined at 1 and 3 months postintervention.

Interobserver Agreement and Treatment Integrity

Interobserver agreement (IOA) was examined for a minimum of 30% of the sessions within each of baseline, intervention, and generalization conditions for each skill. A trained research assistant scored IOA only from video-recorded sessions in which both the interventionist’s profile and child’s eyes gaze were easily discernible. Both the interventionist and the observer recorded data on the same data sheets for baseline and intervention. Agreements occurred when both the interventionist and the observer scored the same response on the same opportunity during intervention and generalization sessions and were calculated on an opportunity-by-opportunity basis by dividing the number of agreements by the total number of opportunities, multiplied by 100. A minority (2.5% for Edward, 3.9% for Neil, and 5.5% for Trevor) of IOA scores were below 80% and considered outliers. Average IOA was calculated including these outliers with the number and percentage IOA for the outliers also reported.

For Trevor, IOA was collected for 57% of baseline, 30% of generalization, and 45% of intervention sessions. Mean IOA was 95% (range 80%–100%) for baseline, 86% (range 80%–100%, with one outlier at 60%) for generalization, and 94% (range 80%–100%, with two outliers at 60% and 70%) for intervention. For Edward, IOA was collected for 37% of baseline, 35% of generalization, and 39% of intervention sessions. Mean IOA was 98% (range 80%–100%) for baseline, 92% (range 80%–100%, with two outliers at 60%) for generalization, and 94% (range 80%–100%) for intervention sessions. For Neil, IOA was collected for 46% of baseline, 35% of intervention, and 32% of generalization sessions. Mean IOA was 98% (range 80%–100%, with one outlier at 60%) for baseline, 92% for generalization (range 80%–100%, with two outliers at 60%), and 92% (range 80%–100%) for intervention sessions.

A trained research assistant collected treatment integrity (TI) data for a minimum of 30% of the sessions across baseline, intervention, and generalization conditions for each skill. The observer assessed intervention integrity on a data sheet listing the specific procedural steps described previously for baseline, generalization, and each skill taught in intervention. Percentage of correct implementation was calculated by diving the number of times the observer scored the interventionist as correctly implementing the component of the treatment by the total number of correct plus incorrect implementations, multiplied by 100.

For Trevor, TI was collected for 60% of baseline, 45% of generalization, and 44% of intervention sessions. Mean TI was 99% (range 92%–100%) for baseline, 100% for generalization (range 100%), and 100% (range 96%–100%) for intervention. For Edward, TI was collected for 37% of baseline, 35% of generalization, and 32% of intervention sessions. Mean TI was 99% (range 87%–100%) for baseline, 100% (range 95%–100%) for generalization, and 100% (range 96%–100%) for intervention sessions. For Neil, TI was collected for 43% of baseline, 38% of generalization, and 35% of intervention sessions. Mean TI was 99% (range 96%–100%) for baseline, 100% (range 100%) for generalization, and 100% for intervention (range 97%–100%).

Results

RR, SR, RJA, and IJA Intervention

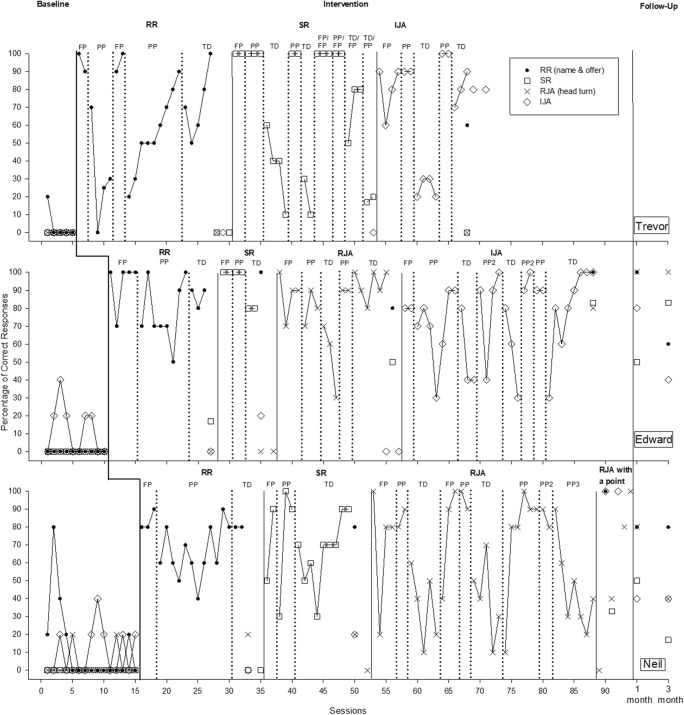

Figure 1 shows performance for all children during baseline and intervention sessions. Closed circles represent RR performance, open boxes represent SR performance, crosses represent RJA performance, and open diamonds represent IJA performance. During full- and partial-prompt conditions, percentage of correct responses include any prompted and, if they occurred, independent responses. During the time delay condition, percentage of correct responses included only independent responses (i.e., those that occurred before the end of the time delay and the interventionist’s prompt). During initial baseline sessions before intervention began for any skill, all children performed between 0% and 40% for each skill, with the exception of Neil, who performed at 80% during one RR baseline session. For all children, RR performance increased only when intervention was introduced. However, not all children acquired each skill and some required modifications of procedures. All children mastered RR and IJA in 16–22 sessions and 15–31 sessions, respectively. Each child’s performance will be discussed next.

Fig. 1.

Trevor’s, Edward’s, and Neil’s performance during baseline, intervention, and follow-up. FP = full prompt, PP = partial prompt, TD = time delay. PP2 and PP3 refer to individualized partial prompts

Trevor

The first panel of Fig. 1 shows Trevor’s performance during baseline and intervention for RR, SR, and IJA. Trevor met mastery criterion for RR with the reintroduction of an FP one time when performance declined during PP.

After mastery of RR, performance during baseline probes of SR, RJA, and IJA remained low at 0%. When intervention was introduced for SR, performance increased and remained high when the FP was faded to a PP. During TD, Trevor’s performance declined even after reintroduction of a PP. At this point the interventionist modified prompts to include an FP/PP chain procedure (described in Table 3). Performance remained high when fading the GS response from an FP to a TD; however, when prompts were faded for the behavioral response from an FP to a PP, performance declined. SR intervention lasted 23 sessions without meeting mastery criterion. At this point, Trevor showed the gaze shift response to RR and in the first part of SR, the same response taught in IJA, but continued to perform at IJA at 0%. We decided to teach IJA next and resume SR intervention after IJA acquisition. However, shortly after we began IJA, scheduling conflicts with Trevor’s ongoing services and activities necessitated ending intervention. At the completion of IJA, the interventionist probed for generalization to RJA and SR. Trevor acquired IJA after intervention began, only requiring the reintroduction of a PP once when responding decreased during TD. Although performance during probes of RJA and SR continued to be low at 0%, intervention ended due to scheduling conflicts and Trevor could not be reached for follow-up.

Edward

The second panel of Fig. 1 shows Edward’s performance during baseline, intervention, and follow-up for RR, SR, RJA, and IJA. Edward met mastery criterion for each of the four skills once intervention began and continued to show performance above baseline levels as subsequent skills were targeted in intervention. After meeting mastery criterion for a skill, performance during baseline probes of untaught skills remained low at 0%–20%. He required the reintroduction of a PP once for RJA when performance declined during TD. During IJA, he also required the introduction of a modified second partial prompt (PP2) twice when performance declined during the TD condition.

During the 1-month follow-up, Edward performed all skills at mastery levels, with the exception of SR, which declined to 50%. During the 3-month follow-up, Edward performed SR and RJA at mastery levels, but performance of RR and IJA declined to 60% and 40%, respectively.

Neil

The third panel in Fig. 1 displays Neil’s performance during baseline, intervention, and follow-up for RR, SR, RJA, and IJA. Neil acquired RR and SR after intervention began, but his performance of RJA and IJA during baseline probes remained low at 0%–20%.

Neil’s performance during RJA increased when intervention began but decreased during TD. The interventionist reintroduced a PP, but when she faded the prompt from a PP to a TD, Neil’s performance once again declined. The interventionist reintroduced a PP again, and Neil’s performance increased. The interventionist then faded to a second partial prompt (PP2). When she faded to a third partial prompt (PP3), Neil’s performance declined. At this point in intervention, both interventionists working with Neil conducted a number of informal probes modifying the antecedent, prompt, and motivation to determine how to tailor RJA intervention to improve performance. All probe sessions consisted of 4–10 opportunities depending on the child’s availability. The interventionists conducted the following probes: a verbal “do this” prompt (probed during four sessions with performance between 17% and 40%); a verbal “look” prompt (probed in one session with performance at 20%); a TD 30 s prompt (probed during two sessions with performance at 25%); a prompt in which the interventionist turned her head but also leaned her body toward the item (probed one session with performance at 0%); a preference assessment conducted before presenting an RJA opportunity, which used the preferred item as the RJA toy during the opportunity (probed during two sessions with performance at 10% independent correct responses), and a fading within session from an FP to a PP to a TD 4 s (probed during two sessions with performance at 0% independent responses). The interventionists also conducted four probe sessions in which the interventionist modified the antecedent and turned her head and pointed toward the item (instead of just turning her head as she had done before). Neil demonstrated mastery of RJA when the interventionists pointed as part of the modified antecedent. Although previous probes are not graphed, the four probes of RJA with a head turn and point are shown to demonstrate mastery of RJA. After acquiring RJA with a point, Neil showed mastery levels of performance during IJA.

During the 1-month follow-up, Neil’s performance of RJA and RR remained at mastery levels and performance of SR and IJA declined to 50% and 40%, respectively. During the 3-month follow-up, Neil’s performance of SR, RJA, and IJA declined to 17%, 40%, and 40%, respectively. His performance during RR remained at 80%.

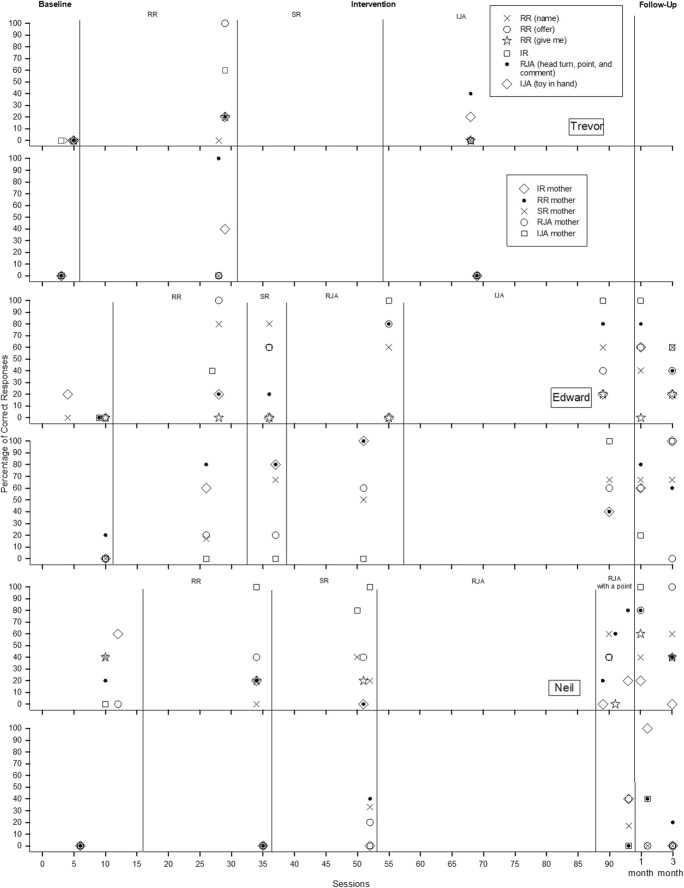

Generalization Across Skills

Figure 2 shows each child’s generalization performance. For each pair of panels, the top panel shows generalization across skills and the bottom panel shows generalization to each child’s mother. For the top panel in each pair, crosses represent RR (name); open circles represent RR (offer); open stars represent RR (give me); open squares represent IR; closed circles represent RJA (head turn, point, and comment); and open diamonds represent IJA (toy in hand). During generalization baseline sessions before intervention began, performance was low at 0%–20% for all children, with the exception of IJA (toy in hand) at 60%, RR (give me) at 40%, and RR (name) at 40% for Neil.

Fig. 2.

Trevor’s, Edward’s, and Neil’s performance during generalization to other skills and with their mothers, probed during baseline, intervention, and follow-up

Trevor

The first panel in Fig. 2 shows Trevor’s performance during generalization to other skills. After Trevor reached mastery criterion for RR, his performance of two other requesting skills, but no other skills, increased: IR and RR (offer), which were 60% and 100%, respectively. Because he did not master SR and we did not teach RJA, generalization was not probed again until mastery of IJA, when RJA (head turn, point, and comment) increased slightly to 40%, but all other skills decreased or remained low (0%–20%). Trevor could not be reached for follow-up.

Edward

The third panel in Fig. 2 shows Edward’s performance during generalization to other skills. When Edward mastered a skill, performance during generalization probes of similar skills increased to levels above baseline with the exception of RR (give me) and IJA (toy in hand), which remained low at 0%–20%. During the 1-month follow-up, Edward’s performance during IJA (toy in hand) increased to 60%. All other skills remained at levels above baseline (40%–100%), with the exception of RR (give me). During the 3-month follow-up, Edward’s performance decreased below mastery but remained above baseline levels (40%–60%), with the exception of RR (give me) and IJA (toy in hand) at 20%.

Neil

The fifth panel of Fig. 2 shows Neil’s performance during generalization to other skills. After mastering RR, performance of two other requesting skills increased: IR and RR (offer) increased to 100% and 40%, respectively. All other skills remained low or decreased slightly from baseline. After Neil mastered SR, performance of IR remained high (80%–100%), and RR (offer) remained at slightly increased levels (40%). Performance of all other skills remained low or at similar levels to baseline (0%–40%). After Neil mastered RJA (head turn with a point), performance of RJA (head turn, point, and comment) increased (80%) and RR (name) also increased slightly (60%). Performance of IR decreased slightly but remained above baseline levels (40%). Performance of all other skills remained low (0%–40%).

During the 1-month follow-up, Neil’s performance of RR (give me) and RR (offer) increased to 60% and 80%, respectively, whereas all other skills decreased slightly or remained at levels similar to those observed throughout intervention. During the 3-month follow-up, Neil’s performance of IR and RJA (head turn, point, and comment) decreased to 40%. All other skills remained at similar levels as the 1-month follow-up.

Generalization With Parents

Figure 2 also shows each child’s performance with his mother. For each pair of panels, the bottom panel shows generalization with parents for a given child. For the bottom panel in each pair, open diamonds represent IR, closed circles represent RR, crosses represent SR, open circles represent RJA, and open squares represent IJA. For all children, performance with their mothers at baseline was 0% for all skills, with the exception of RR at 20% for Edward.

Trevor

The second panel in Fig. 2 shows Trevor’s performance with his mother. After acquisition of RR, performance with his mother increased to 100% for RR, but only 40% for IR, and SR, RJA, and IJA remained low. After acquisition of IJA, performance of all skills decreased or remained low (0%). Trevor could not be reached for follow-up.

Edward

The fourth panel of Fig. 2 shows Edward’s performance with his mother. For all skills, once Edward mastered a skill with the interventionist, his performance increased for similar skills with his mother. At the 1-month and 3-month follow-ups, Edward’s performance with his mother remained at similar levels as throughout intervention, with the exception of IJA during the 1-month follow-up, which decreased to 20%, and RJA during the 3-month follow-up, which decreased to 0%.

Neil

The sixth panel of Fig. 2 shows Neil’s performance with his mother. After Neil acquired RR, performance with his mother remained low (0%). After he acquired SR, performance of RR (40%) and SR (33%) with his mother increased slightly. Performance of all other skills remained low (0%–20%). After Neil acquired RJA with a point and generalized to IJA, performance of RJA with a point and RR (offer) with his mother increased slightly (40%). Performance of all other skills remained low (0%–20%). During the 1-month follow-up, Neil’s performance with his mother remained at low or slightly increased levels, with the exception of IR, which increased to 100%. During the 3-month follow-up, Neil’s performance of all skills was at low levels (0%–20%).

Discussion

Results replicated previous literature by demonstrating that, in general, prompting and reinforcement resulted in acquisition of RR, SR, RJA, and IJA for two children with ASD. However, one child acquired RR and IJA, but not SR, even after changes to procedures (we did not teach RJA due to schedule conflicts that prohibited continued participation). Children showed variable generalization with their mothers, to other social communication skills, and maintenance across time. In general, for Edward, after a skill was acquired, he demonstrated increased performance of that skill with his mother. For Trevor and Neil, generalization with their mothers was more limited. Intervention involving more than one therapist may promote generalization across social partners, and parent training may encourage parents to prompt and reinforce these skills outside of intervention.

After children acquired RR, they showed some generalization to similar requesting skills, such as initiating a request, but none showed generalization to other types of skills (SR, RJA, and IJA). This is in contrast to Krstovska-Guerrero and Jones (2016) and Muzammal and Jones (2017), in which acquisition of RR led to increased levels of IJA and RJA for some children, and other literature, in which children were taught to mand (e.g., Charlop-Christy et al., 2002). None of the children showed generalized performance to RR (give me) either. It could be that RR (give me) serves a different function than the other requesting skills, or that motivation is different for this skill. In RR (offer) and IR, the child has no toy and receives a toy after shifting gaze. In RR (give me), the child already has the pieces to a toy when the interventionist extends her empty palm. Although the child was not required to hand over a piece of the toy, the child likely had a history of an empty palm serving as a discriminative stimulus to hand over something, without needing to shift gaze.

Unlike Krstovska-Guerrero and Jones (2016) and Muzammal and Jones (2017), we also taught SR. SR is a deficit in children with ASD, and the observing response is similar to the GS response during JA. For the two children who acquired SR, acquisition of SR did not lead to increases in JA. One reason for a lack of generalization across SR and IJA may be that the antecedent stimuli were different. For example, during SR the antecedent stimulus was always a box, whereas during JA the stimuli used were toys with which the child was familiar. The function of the responses during SR and JA may also be different enough to hinder generalization. The GS response during SR leads to the child gaining information during an uncertain event related to accessing or avoiding an item, and during JA the child gains purely social attention (e.g., interventionist smiling and commenting).

Children also showed limited generalization to JA, unlike in Krstovska-Guerrero and Jones (2016) and Muzammal and Jones (2017). After Edward acquired RJA (head turn) and Neil acquired RJA (head turn with a point), their performance generalized to a different RJA skill in which the interventionist turned her head, pointed toward a toy, and commented. Neil was the only child who demonstrated generalization to IJA after acquiring RJA. Consistent with literature showing that learning RJA leads to very minimal or no gains in IJA for at least some children (e.g., Martins & Harris, 2006; Muzammal & Jones, 2017; Rocha, Schreibman, & Stahmer, 2007), only Neil demonstrated generalization from RJA to IJA. And none of the children generalized from IJA to a different IJA (toy in hand) skill in which they had access to a similar toy.

At the 1- and 3-month follow-ups for Edward and Neil, performance of skills with the interventionist and the children’s mothers was variable with most skills below mastery level. One limitation is that Trevor was not available for follow-up. As mentioned previously, training parents to implement intervention may increase the likelihood of generalization across skills and maintenance of skills over time.

In addition to performing variably during the generalization probes, all children required individualized procedures for different target skills. Although these results contrast with previous research in which all children responded to the same intervention procedures (Krstovska-Guerrero & Jones, 2016; Muzammal & Jones, 2017), other studies suggest that individualized procedures are often required for at least some children (e.g., Rudy et al., 2014; Taylor & Hoch, 2008). Whereas modification of the independent variable is considered an experimental weakness, it may also be considered a clinical strength. Describing the decision-making process for modifications to intervention procedures provides interventionists with an idea of how to proceed when children do not respond to intervention, something that happens often. In this study, individualized procedures included reintroducing a prompt, modifying prompts, and modifying antecedent opportunities. In general, a previously successful prompt was reintroduced when performance declined, with the exception of Edward during IJA because he stopped responding to the partial prompt during error correction. Reintroducing a prompt worked well for some children and skills. In some instances, reintroducing a prompt was not successful and modification of a prompt or antecedent was required. We will discuss each child next in terms of how we modified prompts and antecedents.

Trevor

For SR for Trevor, we modified the prompting procedure and the response to a chain in which the observing response was taught first, based on the effectiveness of similar chaining strategies in previous literature (Brim et al., 2009). Even with modified prompts, Trevor did not acquire SR. Trevor’s history opening boxes may have impacted performance. He often approached the box and said, “Happy birthday,” or “Open the box,” even when the interventionist was frowning and shaking her head. Similar to Taylor and Hoch (2008), the interventionist may have considered Trevor’s learning history when modifying prompts. Given Trevor’s history of vocally responding in the presence of boxes and his learning history of following vocal directions, there are additional modifications that may have been effective but were not implemented due to time constraints. Varying the stimuli in which the item was placed (e.g., bag, cloth, container) and modifying the prompt by pairing the affective cue with a verbal cue such as “no” or “yes” (faded after mastery) may have been effective.

Edward

Edward stopped responding to the original partial prompt during IJA. Similar to Kryzak and Jones (2015), in which a preassessment was used to determine what prompt would evoke eye contact in children with ASD, the interventionist screened children to determine if they visually tracked moving objects. Because Edward consistently tracked moving objects, the interventionist modified the partial prompt to consist of holding a toy visible in the palm of the her hand as she moved her hand from the IJA toy to her eyes to trace the child’s visual path.

Neil

For Neil during RJA, performance consistently declined when the interventionist faded from a partial prompt to a time delay, suggesting that he may have developed a dependency on the prompt. The interventionist tried gradually fading to less intrusive prompts in which she moved her index finger a quarter of the way to the toy and then a quarter of the way back to her eyes and then eventually she kept her index finger in front of her face but did not move her finger. Performance still declined when the prompt was entirely removed, suggesting that a prompt or antecedent modification may be necessary. Because the interventionist did not have a history of teaching Neil outside of intervention, she asked Neil’s mother about more effective prompts for other similar skills. Based on this report, the interventionist conducted informal probes of modified prompts (e.g., turning her head and leaning her body toward the item), motivation (e.g., conducting a preference assessment before intervention), and antecedents (e.g., pointing her finger and turning her head toward the item) to determine what would work best for Neil. Similar to Kryzak and Jones (2015), in which a manipulation of the antecedent stimuli was necessary for one child to acquire IJA, probes showed that modifying the antecedent to include a point resulted in improvements in Neil’s performance of RJA.

We reintroduced prompts, then modified prompts, and finally modified antecedents to improve children’s performance, generally resulting in acquisition. Future research should continue to examine a variety of procedures for targeting social communication skills and consider variables that might relate to children’s response to intervention.

Consideration for Practitioners Teaching Social Communication Skills

Observations of children’s performance and the modified intervention procedures in this study suggest certain child and intervention characteristics may impact children’s response to social communication skills intervention. Practitioners may consider the following factors when developing similar intervention procedures for children with ASD.

Setting

Sessions took place in each child’s home in either the family’s living room or the child’s bedroom. Although similar to some studies (e.g., Ferraioli & Harris, 2011; Krstovska-Guerrero & Jones, 2016; Muzammal & Jones, 2017), this is in contrast to other studies in which JA intervention occurred in a controlled environment such as a treatment center (e.g., Rudy et al., 2014) or laboratory (e.g., Whalen & Schreibman, 2003). In children’s homes, sessions often occurred in rooms that had many other toys with which the children regularly played. Homes were bustling places with noise from other children or work outside. Any of these factors could impact children’s performance and be more distracting for some children than for others. Preassessments conducted in natural settings, as well as a more controlled setting containing minimal toys, other people, and so forth, could inform how intervention should proceed. If the child responds well on the preassessments in the controlled environment, but not in the natural environment, intervention may begin in a controlled environment with natural elements faded in over time during intervention.

Parent training

In most research studies, the relationship between the interventionist and the child outside of the research study is not clearly described. In recent studies in which JA and/or requesting was taught as part of a larger curriculum of skills, it is likely that the same therapists who taught JA or requesting also taught other skills, thus being very familiar to the child (e.g., Chang, Shire, Shih, Gelfand, & Kasari, 2016; Kaale, Smith, & Sponheim, 2012; Vivanti & Dissanayake, 2016). In both Muzammal and Jones (2017) and Krstovska-Guerrero and Jones (2016), the interventionists also provided intervention focused on other skills to the children outside of the research study (I. Krstovska-Guerrero and M. Muzammal, personal communication, April 10, 2017). In contrast, in the current study the interventionist only saw the children a couple of times a week and only for the purposes of this study. Social communication intervention may be more effective when the interventionist has an established relationship with the child and engages with the child for more time and other instructional programs.

An interventionist who has a long history of providing reinforcement for appropriate behaviors has an opportunity to develop strong instructional control with the child. Parents may be ideal interventionists for early social communication intervention because of their history with reinforcement. Including parents in intervention may also increase the likelihood of generalization because parents can provide natural learning opportunities outside of the intervention context. Recent research has successfully involved parents in JA and social communication intervention with their children with ASD (Gulsrud, Hellemann, Shire, & Kasari, 2016; Kasari, Gulsrud, Wong, Kwon, & Locke, 2010). The lack of generalization to parents in this study suggests that practitioners may consider including parent training. Future research should continue to explore the impact of parent training and including parents in early social communication interventions on skill acquisition, generalization, and maintenance.

Treatment intensity

Treatment intensity is often defined as the amount of intervention provided over time and is reported in terms of the number of sessions administered or how frequently sessions were administered (Warren, Fey, & Yoder, 2007). In many studies of social communication intervention, intervention was relatively intense, occurring daily (e.g., Brim et al., 2009; Gulsrud, Kasari, Freeman, & Paparella, 2007; Kasari, Freeman, & Paparella, 2006) or several days per week (Krstovska-Guerrero & Jones, 2016; Muzammal & Jones, 2017). In this study, the interventionist conducted intervention with each child 1–3 days per week, with children receiving intervention most weeks on 2 days. More frequent sessions may positively impact JA acquisition (Paparella & Freeman, 2015) and likely other social communication skills.

It is also possible that treatment intensity interacts with other child characteristics. For example, Granpeesheh, Dixon, Tarbox, Kaplan, and Wilke (2009) found that gains in treatment for younger children (2–7 years of age) may be greater at higher intensity treatment compared to lower intensity treatment, whereas for older children (7–12 years of age), there was no relationship between treatment intensity and intervention gains. Intensity may also increase if both parents and practitioners were to provide instructional opportunities.

Child characteristics

A number of recent studies focused on social communication skills such as JA have involved very young children with ASD below 5 years of age (e.g., Kaale et al., 2012; Lawton & Kasari, 2012; Schertz, Odom, Baggett, & Sideris, 2013), and many early intervention programs targeting these skills involve children under or just at 3 years of age (Dawson et al., 2010; Devescovi et al., 2016). The children in Krstovska-Guerrero and Jones (2016) and Muzammal and Jones (2017) were quite young, between 20 and 32 months of age, and had just begun receiving early intervention services. The children in this study were between 44 and 50 months of age. Older children have a longer history of receiving services, as well as reinforcement for engaging in other social communicative behaviors that do not include GS. While teaching RR, Edward and Trevor sometimes vocally requested the item during baseline but then did not shift gaze. Thus, they had already learned another mode of social communication to request. Teaching the GS response in addition to other social communication behaviors may promote generalization of behaviors across skills, as well as maintenance over time. In fact, GS along with other topographies has been taught to children with ASD of a similar age (e.g., Krstovska-Guerrero & Jones, 2013; Rudy et al., 2014; Taylor & Hoch, 2008; Whalen & Schreibman, 2003). Future research should continue to explore the effect of teaching multiple and combinations of forms of social communication with young children with ASD. Observation of or a parent- or teacher-completed survey of children’s existing social communicative repertoire may be helpful when planning intervention.

Although it is not clear that children varied significantly on any preassessment administered in this study such as the CARS™-2, PLS™-5, Vineland™-II, or prerequisite skills, there may be other child characteristics that were not measured that play a role in how children responded to intervention. Children did vary in their baseline performance. During baseline, Neil demonstrated higher levels of performance of the GS response than the other two children. Neil was also the only child to generalize from RJA to IJA. Trevor’s performance during baseline was lower than the other children, and he also demonstrated the most limited gains in generalization to other social communication skills. Lower baseline performance may suggest that fading prompts in smaller increments or increasing the frequency of sessions may increase effectiveness and efficiency of intervention and gains in generalization.

Child characteristics, such as attending skills, may inform choice of prompting strategy. Children showing poorer attending may also benefit from fading prompts in smaller steps. Although all children in this study passed the prerequisite test of orienting toward an activated toy and following a moving item, this was observed to be more inconsistent for some children during intervention than during the prerequisite test. A more thorough prerequisite assessment of attending skills on multiple occasions and in different environments containing different distracting stimuli may more accurately capture the child’s attending skills and inform intervention. A thorough preassessment may also help researchers and clinicians determine what skills to teach children who do not meet prerequisite criteria. For example, visually tracking moving items or attending to items in a noisy environment could be taught before beginning social communication intervention. Similar to Kryzak and Jones (2015), a survey of the child’s current therapist or teacher or a baseline assessment of various prompts may reveal prompting strategies that work best for each child.

Summary and Future Directions

Results suggest that, in general, intervention procedures consisting of prompting and reinforcement were effective in teaching requesting, SR, and JA skills to children with ASD. However, not all children acquired each skill and all children required individualized prompting procedures to acquire some skills. Future research should continue to explore social communication intervention including variables that relate to the choice of prompting and reinforcement procedures to improve acquisition, generalization, and maintenance. Determining what variables impact how children respond to intervention and how to modify intervention when children do not respond to intervention may help practitioners plan and individualize future social communication interventions for children with ASD.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the children and their families who participated in this research project, as well as the research assistants who assisted with data collection and video coding: Adriana Villanueva, Esther Jungreis, Lena Khouri, Jessica Wasserman, and Shoshana Linzer.

This research was completed in partial fulfillment for the degree for Doctorate in Philosophy in Psychology, Behavior Analysis Program.

Funding

The corresponding author has received the organization for autism research (OAR) graduate student research grant.

This research was funded in part by the Organization for Autism Research Graduate Research Grant Competition-Lisa Higgins Hussman Donation.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The first author has received the organization for autism research (OAR) graduate student research grant. The second author served as mentor on the grant.

Ethical approval

The institutional review board of Queens College, City University of New York, approved this study. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Parents provided informed consent.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Beuker KT, Rommelse NJ, Donders R, Buitelaar JK. Development of early communication skills in the first two years of life. Infant Behavior & Development. 2013;36(1):71–83. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brim D, Townsend DB, DeQuinzio JA, Poulson CL. Analysis of social referencing skills among children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2009;3(4):942–958. [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y, Shire SY, Shih W, Gelfand C, Kasari C. Preschool deployment of evidence-based social communication intervention: JASPER in the classroom. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2016;46(6):2211–2223. doi: 10.1007/s10803-016-2752-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlop-Christy MH, Carpenter M, Le L, LeBlanc LA, Kellet K. Using the picture exchange communication system (PECS) with children with autism: Assessment of PECS acquisition, speech, social-communicative behavior, and problem behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2002;35(3):213–231. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2002.35-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornew L, Dobkins KR, Akshoomoff N, McCleery JP, Carver LJ. Atypical social referencing in infant siblings of children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2012;42(12):2611–2621. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1518-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, G., Rogers, S., Munson, J., Smith, M., Winter, J., Greenson, J., … Varley, J. (2010). Randomized, controlled trial of an intervention for toddlers with autism: The Early Start Denver Model. Pediatrics, 125(1), e17–e23. 10.1542/peds.2009-0958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- DeQuinzio JA, Poulson CL, Townsend DB, Taylor BA. Social referencing and children with autism. Behavior Analyst. 2016;39(2):319–331. doi: 10.1007/s40614-015-0046-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devescovi R, Monasta L, Mancini A, Bin M, Vellante V, Carrozzi M, Colombi C. Early diagnosis and Early Start Denver Model intervention in autism spectrum disorders delivered in an Italian Public Health System service. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 2016;12:1379–1384. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S106850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube WV, MacDonald RF, Mansfield RC, Holcomb WL, Ahearn WH. Toward a behavioral analysis of joint attention. Behavior Analyst. 2004;27(2):197–207. doi: 10.1007/BF03393180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraioli SJ, Harris SL. Teaching joint attention to children with autism through a sibling-mediated behavioral intervention. Behavioral Interventions. 2011;26(4):261–281. [Google Scholar]

- Ganz JB, Lashley E, Rispoli MJ. Non-responsiveness to intervention: Children with autism spectrum disorders who do not rapidly respond to communication interventions. Developmental Neurorehabilitation. 2010;13(6):399–407. doi: 10.3109/17518423.2010.508298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granpeesheh D, Dixon DR, Tarbox J, Kaplan AM, Wilke AE. The effects of age and treatment intensity on behavioral intervention outcomes for children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2009;3(4):1014–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Gulsrud AC, Hellemann G, Shire S, Kasari C. Isolating active ingredients in a parent-mediated social communication intervention for toddlers with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2016;57(5):606–613. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulsrud AC, Kasari C, Freeman S, Paparella T. Children with autism’s response to novel stimuli while participating in interventions targeting joint attention or symbolic play skills. Autism. 2007;11(6):535–546. doi: 10.1177/1362361307083255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen SG, Carnett A, Tullis CA. Defining early social communication skills: A systematic review and analysis. Advances in Neurodevelopmental Disorders. 2018;2(1):116–128. [Google Scholar]

- Holth P. An operant analysis of joint attention skills. Journal of Early and Intensive Behavior Intervention. 2005;2(3):160–175. [Google Scholar]

- Isaksen J, Holth P. An operant approach to teaching joint attention skills to children with autism. Behavioral Interventions. 2009;24(4):215–236. [Google Scholar]