Abstract

Few attendance interventions have (a) addressed the issue of absenteeism as it applies to part-time adolescent employees, (b) distinguished between planned and unplanned absences, and (c) presented a cost-effectiveness analysis of the intervention. This study employed an A-B-A reversal design, including a small monetary bonus for attendance by part-time adolescent employees. Results indicate a 60% reduction in average group absences during the monetary contingency phase as compared to both baseline phases. The organization spent a total of $264 on monetary incentives during the intervention phase and reduced time spent on hiring and training substitute personnel by approximately 60%. Supervisors reported that a better staff–child ratio helped decrease chaos in the classroom and promoted an overall improvement in the quality of the youth groups.

Keywords: Part-time adolescent employees, Absenteeism, Monetary incentives, Attendance, Cost-effectiveness analysis

Excessive workplace absences can equate to decreased productivity and increased time and money spent hiring and training employee replacements. In 2014, productivity losses due to absenteeism cost U.S. employers $225.8 billion, or $1,685 per employee (Stinson, 2015). The direct costs associated with missed work include overtime pay for other employees or substitute workers and the administrative costs of managing absenteeism, whereas the indirect costs include poor quality of goods or services due to understaffing and poor morale among employees who have to do extra work to make up for their absent coworkers (Investopedia, 2013).

The vast majority of adolescents in the United States work both during the school year and summer months (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2004). A meta-analysis conducted by Martocchio (1989) indicated that both voluntary (planned) and involuntary (unplanned) absences are inversely related to age. Despite this inverse relationship, little research focuses on adolescent behavior in the work environment. Studies often concentrate on the effects of employment on a student’s academic, social, and home life (e.g., Greenberger & Steinberg, 1986).

Interventions that employ bonuses appear to be particularly effective attendance procedures (Landau, 1993). The current study partially replicated the work of Berkovits, Sturmey, and Alvero (2012) on attendance bonuses in adolescent employees with two important changes: (a) a comparison was made between planned and unplanned absences, and (b) a cost-effectiveness analysis was included for both the money and time spent managing absenteeism during each condition. Berkovits et al. (2012) found a substantial decrease in absences upon the implementation of individual- and group-contingent pay bonuses, with a slightly greater decrease during the group contingency. Despite the better attendance obtained during the group contingency, social validity measures indicated that a majority of employees preferred the individual contingency to the group contingency. Therefore, the previously reported employee preference was considered in the design of the current study, and no group contingency was employed. Both researchers and the organization’s management determined this decision to be particularly appropriate to the current setting and age of the participants.

Method

Participants

Twenty-four youth-group leaders (n = 13 female, n = 11 male), aged 13–20 (n = 20 high school, n = 4 college) participated during weekly Saturday-morning youth groups. There was a base pay of $10 a Saturday for eighth graders, with a $1–$2 increment per grade, which yielded a maximum pay of $20 a Saturday for college sophomores. Paychecks were mailed at the end of each month. No subject attrition occurred throughout the duration of the study. Approximately 125 children in nursery through sixth grade attended weekly Saturday-morning groups that lasted 1.5 h. There were nine groups. Between two and four leaders led each group.

Dependent Variables and Measurement

The dependent variable was the number of planned and unplanned leader absences per session. The leader contract stipulated that a leader who desired a weekend off from work must e-mail notification to the youth director (first author) by 11:59 p.m. on the Monday evening preceding the desired weekend off. Such absences were considered “planned.” The youth director saved these e-mails in an electronic folder and then recorded impending absences on an attendance sheet containing dates for each Saturday of that month and each employee’s name. The youth director printed a copy of the updated attendance sheet every Friday, which an on-duty observer used on Saturday morning to record staff presence. If a leader was absent without advance notification, the observer marked the absence as “unplanned.”

The first time a leader was absent without advance notification, the youth director sent the leader a written warning. The second time, the leader was placed on probation. The third time, the leader was subject to dismissal. As per the leader contract, this policy was in place for the 3 months preceding the study and remained in effect throughout its duration. No one was dismissed as a result of this policy.

Following each Saturday session, the youth director transferred absent marks onto an electronic copy of the attendance sheet stored in a locked folder on the youth director’s computer. For confidentiality, the youth director destroyed the hard copy once the transfer of data was complete.

Reliability

The youth director and a research assistant served as primary and secondary observers, respectively. Interobserver agreement (IOA) was calculated following the procedures described in Berkovits et al. (2012) for e-mail notifications and on-site observations. IOA for e-mail notifications averaged 99% and ranged from 96% to 100%, whereas IOA for on-site attendance averaged 99% and ranged from 92% to 100%.

Experimental Design

The participants were exposed to an A-B-A sequence: baseline (A), monetary contingency (B), and return to baseline (A). Baseline and return-to-baseline phases included recording of intended absence notifications, as well as on-site attendance. Observation and recording procedures for the baseline and return-to-baseline phases were identical to those described in Berkovits et al. (2012).

Procedure

Baseline

The youth director e-mailed all leaders regarding the absence-notification e-mails and their contingent rules. This e-mail stressed the importance of consistent attendance and planned absences.

Individual Contingency

The youth director informed all leaders via e-mail that an extra $2 would be added to their paychecks for every week that they were present at work. After recording each session’s attendance, the on-site observer informed leaders that were in attendance that they had earned a $2 bonus. All leaders received an extra $2 in their paychecks for each week that they were in attendance.

Return to Baseline

The youth director e-mailed all leaders regarding the termination of the individual contingency and included the information from the baseline e-mail. No monetary contingency was in place for attendance.

Data Analysis

It was determined a priori that an experimental effect would be considered present if a substantial decrease in total group absences or a reversal from upward trend to downward trend occurred during the monetary contingency phase.

Results and Discussion

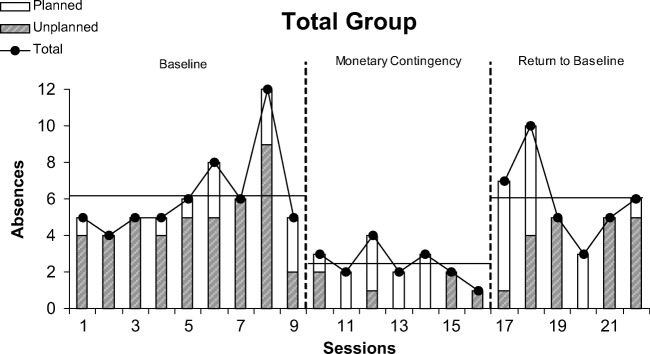

The monetary contingency decreased group absences as compared to the baseline and return-to-baseline phases. As can be seen in Fig. 1, an average of 6.22 leaders were absent per session during the baseline phase (range 4–12, SD = 2.44). In the monetary contingency phase, total group absences were reduced by half and averaged 2.43 leaders per session (range 1–4, SD = 0.98). When the monetary contingency was withdrawn in the return-to-baseline phase, absences once again increased to an average of 6 per session (range 3–10, SD = 2.37). A decrease in data variability for the monetary contingency phase compared to both baseline phases can be seen in Fig. 1. The last data point in baseline was quite low compared to the preceding four data points, thus giving the illusion of a possible downward trend. However, absences during the monetary incentive phase were consistently lower than the last baseline point, and absences increased when the incentives were eliminated.

Fig. 1.

Group planned and unplanned absences for baseline, monetary contingency, and return-to-baseline phases

It should be noted that the institution at which this research was conducted organized a teen leader social-action mission to New Orleans on Weekend 5 of data collection during the baseline phase. The seven participants who chose to participate in this mission were not included in the number of absences recorded for that day. In addition, the local high school, attended by many of the participants, scheduled a school-wide weekend retreat that coincided with Session 15 of the monetary contingency phase. Once again, the 10 leaders who chose to participate in the retreat were not included in the number of absences for that day.

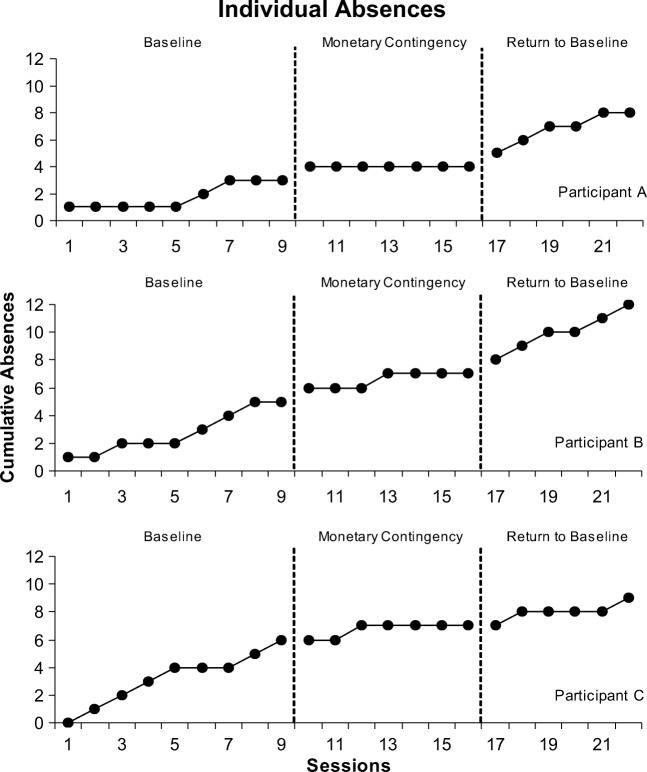

Figure 2 shows cumulative absences for three participants with the greatest number of total absences across all 22 sessions of the study. Data for Participant A indicate that the monetary contingency was successful at eliminating absences for that participant. This effect is evident by the flat slope during intervention as compared to the increasing slope during baseline and the steep slope of the function during return to baseline. Data for Participants B and C indicate absences during the monetary contingency phase and sessions of no absence during both baseline phases. Nonetheless, Participant B displayed a strong contrast between the shallow function of the monetary contingency and the steep function displayed during the last five sessions of baseline and the entire return to baseline. Similar results were obtained for Participant C, who demonstrated only one absence during the monetary contingency, a steep increase in absences during baseline, and two absences during return to baseline.

Fig. 2.

Individual cumulative data for baseline, monetary contingency, and return-to-baseline phases for three participants with the highest absentee rates

Payroll averaged $715 per baseline session and $773 per intervention session. Employees were paid a total of $264 in incentive pay. According to the youth director, the average amount of time spent finding replacement staff was 15–30 min per absence. Based on these self-reported time estimates, management spent a minimum average of 86 min per baseline session finding someone to replace the absent employees. This average decreased to 36 min during intervention; a savings of 1 h per work session. As the youth director was a salaried employee, a cost-benefit analysis was not applicable to assess the advantages of the intervention. Therefore, it was determined that a cost-effectiveness analysis, which is a form of economic analysis that compares costs and qualitative effects (Yates, 1994), would be more appropriate. The youth director reported a decrease in stress, less time spent staying late, and an overall increase in efficiency of the youth programming (e.g., when replacements could not be found, the quality of the program suffered).

There was a greater proportion of unplanned absences compared to planned absences throughout the baseline and return-to-baseline phases, where unplanned absences averaged 78.57% and 55.56%, respectively, of all total absences. In contrast, unplanned absences composed a minority of total absences during the monetary contingency phase, averaging 41.18% of all total absences. Despite the higher proportion of unplanned absences during the return-to-baseline phase compared to the monetary contingency phase, unplanned absences never recovered to preintervention levels.

Considering that the intervention did not target advance communication of absences, it is unclear why planned absences increased during the monetary contingency phase. It is possible that response generalization, in which a functionally similar, yet nontargeted behavior is influenced by the operations of an intervention (Camden, Price, & Ludwig, 2011), accounted for the increase in planned absences. Put colloquially, it is possible that “responsible behavior” as applied to the behavior of showing up to work generalized to another response related to responsible behavior, that of advance communication of impending absences. The failure of the unplanned absences to achieve preintervention levels may indicate a small carry-over effect of the response generalization caused by the monetary contingency.

Although lateness was not a dependent measure, an attempt was made to collect data on this variable. Due to practical considerations, such as the difficulty in obtaining accurate and reliable arrival times, lateness was recorded nominally for each participant, with only an “L” marked beside the names of late participants. Valuable information may have been overlooked using this method of recording, as there is no way of distinguishing between participants who arrived 1 or 35 min late. Therefore, any perceived relationship between absences and tardiness based on the obtained data remains limited.

This study precluded extensive staff training and required little monitoring of participant behavior. Data collection followed regular organizational procedures, consisting of minimally obtrusive observation and recording. These observations were executed from outside the group rooms, by using classroom windows and by recording attendance as the leaders entered the facility. Administration of the reinforcement itself did not take any additional time, and the cost to the organization was minimal (approximately $38 per intervention session). Informing leaders of the various study phases took little time and reached them quickly, as messages were sent out by e-mail, a popular method of communication among high school students. As is the case in all organizations, ease of implementation and seamless integration into an already-existent daily schedule are important factors in adherence to implementation guidelines.

As a result of the monetary contingency’s effectiveness, the supervisory staff in this setting needed to spend less time dealing with individual leader absences and, consequently, less time was spent in the hiring and training of replacement leaders. In addition to the managerial-reported benefits of this experiment, leaders also reported that a better staff–child ratio helped to decrease chaos in the classroom and promoted calm and orderly activities, resulting in a more collegial and pleasant environment. There are two important limitations that should be noted. First, a second return to intervention was not included in the current design, thus limiting the strength of experimental control. Second, all reported employee and management benefits were obtained through informal reports to the youth director, and no formal social validity measure was conducted. Future research should consider administering a social validity measure to employees, management, and clients as a means of formally assessing such reported benefits to help strengthen the conclusions of a cost-effectiveness analysis.

Implications for Practice

This study offers useful information for organizations that employ teenagers and college-aged students.

This study may provide guidance to those considering the use of monetary incentives to improve employee attendance.

Consideration is given to the differences in planned versus unplanned absences, and a cost-effectiveness analysis of the intervention is provided.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the youth group leaders and their parents for participation in this study and the organization for its support. The authors also wish to thank Ari Friedman and Dr. Ari Spiro for their dedication to the project and assistance with data collection.

Funding

This study was not funded.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

The work described has not been published before. It is not under consideration for publication anywhere else, and its submission for publication has been approved by all coauthors.

Contributor Information

Shira Melody Berkovits, Phone: (917) 455-1303, Email: shira@jewishsacredspaces.org.

Alicia M. Alvero, Phone: (718) 997-3212, Email: alicia.alvero@qc.cuny.edu

References

- Berkovits MS, Sturmey P, Alvero AM. Effects of individual and group contingency interventions on attendance in adolescent part-time employees. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 2012;32(2):152–161. doi: 10.1080/01608061.2012.676495. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Camden MC, Price VA, Ludwig TD. Reducing absenteeism and rescheduling among grocery store employees with point-contingent rewards. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 2011;31(2):140–149. doi: 10.1080/01608061.2011.569194. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberger, E., & Steinberg, L. (1986).When teenagers work: The psychological and social costs of adolescent employment. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Investopedia. (2013). The causes and costs of absenteeism in the workplace. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/investopedia/2013/07/10/the-causes-and-costs-of-absenteeism-in-the-workplace/#79f70a4a3eb6

- Landau JC. The impact of a change in an attendance control system on absenteeism and tardiness. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management. 1993;13(2):51–70. doi: 10.1300/J075v13n02_05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martocchio JJ. Age-related differences in employee absenteeism: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging. 1989;4:409–414. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.4.4.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinson, C. (2015). Worker illness and injury costs U.S. employers $225.8 billion annually. Retrieved from https://www.cdcfoundation.org/pr/2015/worker-illness-and-injury-costs-us-employers-225-billion-annually

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2004). Employment of teenagers during the school year and summer. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/nls/nlsy97r5.pdf

- Yates BT. Toward the importance of costs, cost-effectiveness analysis, and cost-benefit analysis into clinical research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:729–736. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.62.4.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]