Abstract

Appropriate use of function-based assessments and interventions is crucial for improving educational outcomes and ensuring the well-being of children who engage in dangerous problem behaviors such as pica. A function-based assessment was conducted for a child engaging in pica in an inclusive childcare setting. Results suggest pica was maintained by access to adult attention. Function-based interventions were developed, assessed, and shared with the child’s teaching team. Follow-up data suggest that his teachers continued to use the intervention and that levels of pica remained low.

Keywords: Functional analysis, Early childhood, Playground, Pica

Pica—the persistent ingestion of nonnutritive substances—carries serious health risks (Wasano, Borrero, & Kohn, 2009). Function-based assessment and intervention are considered to be gold standard tertiary supports for problem behaviors (Dunlap & Fox, 2011), and a robust literature supports the use of functional analysis (FA) for identifying maintaining consequences of pica to design effective interventions. Although effective intervention approaches for addressing behavioral needs of young children with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) exist, the discrepancy between research and implementation in community-based early childhood programs is considerable (Metz & Bartley, 2012). This may be especially true for children with IDD who engage in less common topographies of problem behavior, such as pica. These behaviors occur more often in individuals with disabilities than in those without but, even so, are relatively rare (Ali, 2001).

Research related to pica has primarily focused on adults or school-aged children (Carter, Wheeler, & Mayton, 2004). A recent review outlined the use of overcorrection, contingent aversive stimulation, and other punishment-based procedures to reduce pica and its associated risks (Williams & McAdam, 2012). However, these interventions are unlikely to be widely accepted in early childhood settings (Brown & Conroy, 2011). FAs of pica can be conducted using safe-to-ingest substances in contrived environments, but access to these assessments is uncommon and the extent to which they are generalizable to typical conditions (e.g., playgrounds) is unknown.

More research is needed regarding the implementation of experimental FAs and interventions in inclusive early childhood settings, such as childcare and Head Start classrooms (Dunlap & Fox, 2011). The identification of effective interventions that can be implemented in early childhood settings might preclude future problems and prevent or reduce the need for punishment-based or more invasive interventions. The purpose of this study was to determine whether an FA resulted in the identification of a maintaining function for a child’s pica in an inclusive early childhood program and whether function-based intervention procedures resulted in decreases in pica.

Method

Participant, Implementers, and Setting

Luke was a White 4-year-old with Down syndrome; he used one-word approximations and was proficient at using an iPad with Proloquo2Go software to make requests but seldom used it without prompting. He rarely engaged with peers and frequently emitted repetitive behaviors, including pica. Teachers reported that Luke never self-restricted food intake and that he ate a variety of inedible items during all activities, but at especially high rates on the playground. Prior to assessment, teachers responded to pica by verbally reprimanding Luke (e.g., “No eat.”) and verbally or physically redirecting him to bite a rubber chewy (worn around his neck). Redirection to the chewy was at the direction of his occupational therapist.

Three graduate students in special education working toward certification as behavior analysts and teachers, under the supervision of two doctoral-level Board Certified Behavior Analysts (BCBAs), implemented most sessions (see Table 1). All sessions occurred in an inclusive, university-affiliated childcare facility during regularly scheduled playground activities. This facility did employ special education teachers but did not have any staff members who were BCBAs nor staff whose role was to provide instructional or behavioral supports to teachers. Approximately 20 other children and 4–8 adults were present during sessions. The FA, first intervention comparison condition, and follow-up session were conducted during the first 10 min of morning or afternoon playground activities; sessions for the second intervention comparison were conducted during the first 25 min of morning playground activities (i.e., two 10-min sessions with a 5-min break between sessions).

Table 1.

Summary of functional assessment and intervention procedures and implementers

| Activity | Components | Results | Implementers | Role | Race |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observation and Interview | ABC data collection, teacher interview | Potential functions identified: attention, tangible, automatic. |

Mona Katie |

GSR GSR |

AI/AN White |

| FA | Attention, tangible, play, ignore | Function identified: attention. |

Mona Katie |

GSR GSR |

AI/AN White |

| Intervention Comparison 1 | DR N, DR N+C, NCA+AMS | Low-effort interventions did not result in acceptable levels of pica. |

Mona Katie |

GSR GSR |

AI/AN White |

| Intervention Comparison 2 | Continuous attention, control | Continuous attention resulted in near-zero levels of pica. |

Mona Cora |

GSR GSR |

AI/AN White |

| Follow-Up | Classroom staff delivery of intervention | Classroom staff implementation maintained near-zero levels of pica. |

Ava Molly Meg Hattie |

Teacher Assistant Student worker SPED teacher |

White Black White White |

GSR, graduate student researcher working toward teacher and behavior analyst certifications; ABC, antecedent, behavior, consequence; DR N, differential reinforcement of no pica without chewy exception; DR N+C, differential reinforcement of no pica with chewy exception; NCA+AMS, noncontingent attention plus antecedent materials setup; SPED, special education; AI/AN, American Indian/Alaskan Native

Response Definitions and Materials

Researchers recorded sessions using a Canon VIXIA Mini camcorder and collected data using timed-event recording via video using Procoder DV software (Tapp, 2003). A single instance of pica was recorded when Luke brought any inedible object, excluding his chewy, toward his mouth and broke the plane of his lips. Pica was reported as a total number of occurrences per 10-min session. Stationary playground equipment and additional portable materials commonly available on the playground (balls, tunnels, scooters) were used.

Experimental Design

Potential functions were assessed in the context of a multielement design. Treatment comparisons were conducted using alternating-treatments designs (Barlow & Hayes, 1979).

Assessment

Structured observations were conducted using in situ antecedent-behavior-consequence (ABC) event recording to inform the FA. Observations suggested common antecedents for pica were diverted adult attention (54%) and attention from a nonproximal adult (more than 5 m away; 27%). Consequences often occurred in tandem; the most common were verbal reprimands (81%), physical redirection to the chewy (63%), and increased adult proximity (45%).

Implementers conducted four FA conditions: play, ignore, tangible, and attention. The order of conditions was randomized. One to two sessions per day were conducted, separated by approximately 4 h. During all sessions, the implementer ignored all nonpica problem behavior, removed inedible items via finger sweep while avoiding eye contact, and always removed the chewy following 30 s of access. During conditions in which pica would have traditionally been ignored, a delayed finger-sweep procedure was used for every occurrence of pica to decrease the likelihood of injury (i.e., accidental ingestion). No differential consequences were available for chewy use in any condition, except that it was removed after 30 s if Luke did not remove it himself. Access to playground equipment was never restricted; observations and teacher report suggested these materials were neutral rather than preferred. During ignore, tangible, and attention conditions, the implementer was at least 2 m away from Luke unless she was implementing a consequence. During play conditions, she was within 2 m of Luke at all times.

During the play condition, the implementer provided continuous attention (e.g., singing, spinning). If Luke engaged in pica, she continued playing without attending to pica, then removed the item after 30 s using a finger sweep.

During the ignore condition—to maintain Luke’s safety and prevent injury but in contrast to typical ignore conditions—the implementer shadowed him and, if Luke engaged in pica, removed items from his mouth after 30 s using a finger sweep.

During the tangible condition when Luke engaged in pica, the implementer removed items via finger sweep and immediately put the chewy in his mouth, removing it after 30 s. Per initial ABC observations and according to teacher report, the chewy was the only tangible item provided contingent on pica and was therefore the only hypothesized tangible reinforcer. To decrease concerns of Luke’s occupational therapist about chewy removal—but in contrast to typical tangible conditions—the chewy was available around Luke’s neck throughout the session. Despite the presence of the chewy, Luke rarely initiated its use without prompting; however, once he was prompted to use it, he often chewed it for a considerable period of time.

During the attention condition, the implementer provided 30 s of attention prior to the session. If Luke engaged in pica, she provided approximately 1 s of verbal attention (e.g., “Don’t eat that.”) and immediately removed the item using a finger sweep. No other attention was provided.

Intervention Procedures

Intervention Comparison 1

Three interventions for decreasing pica based on the functions identified by the FA were designed to provide attention contingent on nonpica behaviors. These interventions were low effort, in that classroom staff could replicate them without the need for continuous attention; two included differential reinforcement of other behaviors (momentary DRO) and one included noncontingent reinforcement. Luke’s chewy was available at all times.

Differential Reinforcement of No Pica without Chewy Exception (DR N)

The implementer started the session by saying, “Go play.” If Luke had nothing in his mouth at the end of each 1-min interval, she provided praise (e.g., “You have nothing in your mouth!”), physical contact (tickles), and positive commenting for appropriate playground behavior (e.g., “You’re sliding!”). If Luke had anything in his mouth at the end of the interval, she removed the chewy or removed the inedible object using a finger sweep.

Differential Reinforcement of No Pica with Chewy Exception (DR N+C)

Procedures in this condition were similar to those in the DR N condition except that reinforcement for no pica was provided if Luke had nothing or only the chewy in his mouth. The implementer reinforced absence of pica or removed items via finger sweep at 1-min intervals. DRO procedures with a chewy exception were conducted in an attempt to determine whether Luke’s pica behavior was sensitive to contingencies that resulted in reinforcement for chewy use because chewy use may be recommended when pica behaviors are automatically maintained.

Noncontingent Attention Plus Antecedent Materials Setup (NCA+AMS)

Before the session, implementers set up an obstacle course on the playground to facilitate engagement. Prior to starting, the implementer conducted a brief preteaching session to ensure Luke understood how to engage with the materials and then told him to “go play.” If Luke was not engaged in pica at the end of each 1-min interval, she verbally prompted him to play on the obstacle course (e.g., “Let’s jump.”) or with playground equipment (e.g., “Go down the slide!”) for 5–15 s and provided behavior-specific praise. If Luke had anything in his mouth at each 1-min mark, she removed the item or chewy and then provided play prompts (e.g., “Run to the base!”). Thus, regardless of Luke’s behavior, attention was provided, but nonedibles were removed prior to attention. This variation of NCA was used because researchers perceived teachers as unlikely to provide positive attention simultaneously with pica. Regardless, the attention was not contingent on the absence of pica.

Intervention Comparison 2

The second intervention comparison was conducted because none of the original interventions, designed with an emphasis on feasibility, resulted in reduced rates of pica. Thus, a higher effort intervention (i.e., continuous attention) was compared with the typical classroom condition. To improve participant detection of differences between conditions, different implementers conducted each condition.

Typical Classroom Procedures

The implementer engaged in behaviors similar to typical classroom conditions with the addition of frequent planned teacher attention (praise) contingent on no pica. She followed a system of least prompts each time Luke engaged in pica. First, the implementer said, “Take that out of your mouth,” and if Luke did not remove or spit out the item, she used a finger sweep to remove the item. She delivered praise every 1 min contingent on the absence of pica.

Continuous Attention

The implementer provided continuous attention to Luke by imitating his play, singing, and physically prompting him to engage with the playground structures. If Luke was unengaged for more than 5 s, she provided a choice between two activities; if Luke engaged in pica, she immediately removed the item using a finger sweep. This condition was designed to address the attention function of Luke’s problem behavior with antecedent- rather than consequence-based intervention components.

Follow-Up

Immediately after the intervention comparison, implementers met with Luke’s classroom teaching team. They shared results of all comparisons and discussed the need for a high-effort intervention on the playground to maintain safety. The team developed a plan such that one classroom team member would serve as an interventionist on the playground during all playground activities. Approximately 7 months after the final session of Intervention Comparison 2, an implementer who did not participate in the initial study activities video recorded Luke during three typical playground activities for 10 min each to collect follow-up data.

Fidelity and Interobserver Agreement (IOA)

IOA data were collected for at least 40% of all conditions for all assessment and intervention comparisons. Agreement was calculated using a point-by-point method with a 3-s window for agreement and averaged at least 90% across assessment and intervention conditions.

Procedural fidelity data were collected for at least 33% of all conditions for all assessment and intervention comparisons, and fidelity averages for assessment and intervention were 94%. During follow-up sessions, we measured provision of attention using momentary time sampling with 5-s intervals as a proxy for fidelity; across sessions, teachers delivered attention during 72%–79% of intervals.

Results

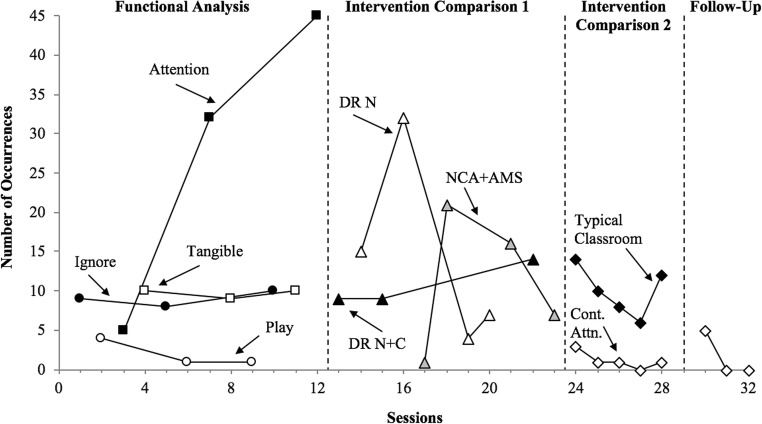

During the initial FA, Luke had the highest levels of pica during the attention condition, with a sharp increasing trend (see Fig. 1). Based on these results, low-effort teacher attention interventions were developed, based on contingent or noncontingent reinforcement paradigms. Levels during these conditions were similar to those in several FA conditions. Because levels were not sufficiently low in any of the low-effort conditions, a second comparison was conducted, with an intervention consisting of continuous antecedent teacher attention. This condition resulted in near-zero levels of pica across five sessions, compared to higher and relatively stable levels in the typical classroom condition. During follow-up, levels of pica remained low.

Fig. 1.

Number of instances of pica behavior during FA assessments, intervention comparisons, and follow-up. DR N = differential reinforcement of no pica without chewy exception; DR N+C = differential reinforcement of no pica with chewy exception; NCA+AMS = noncontingent attention plus antecedent materials setup; Cont. Attn. = continuous attention

Discussion

Results of the analyses suggest that FA procedures can be successfully implemented in an inclusive early childhood context. Moreover, preliminary data suggest the FA provided information that led to the development of a successful intervention, and follow-up data suggest continued use by indigenous implementers. It is possible that differential reinforcement duration (1 s of verbal attention or 30-s access to pica) contributed to differential results during the FA. Short-duration attention was provided because this closely mirrored typical consequences. During Intervention Comparison 2, adult attention successfully competed with pica behaviors.

Prior to Luke’s participation in the study, his teachers typically provided a verbal reprimand and a redirection to the chewy contingent on pica behavior. After the assessment, teacher interactions were provided contingent on not engaging in pica, and inedible items were removed from Luke’s mouth with minimal attention. Moreover, the classroom staff discontinued noncontingent access to the chewy, with no noted increase in pica. Teachers anecdotally reported satisfaction with this change, as it increased congruence between Luke’s behavior and that of his peers. It may have also decreased health risks associated with chewing an object over long periods of time.

None of the low-effort interventions resulted in decreased pica. The data suggested that providing social reinforcement at 1-min intervals was insufficient; these findings are similar to those from previous research, where less intrusive, less intensive interventions were not effective in reducing pica (McAdam, Sherman, Sheldon, & Napolitano, 2004). The higher effort intervention resulted in consistently lower levels of pica. This intervention required continuous adult attention, and although the adults could and often did give attention simultaneously to Luke and his peers, this type of intervention may be difficult to implement in preschools with fewer resources. Given the dangerous topography of pica, early childhood programs should consider temporarily reallocating resources to accurately implement effective interventions given the substantial risks associated with some problem behaviors.

Limitations

First, we were unable to conduct a true ignore FA condition due to safety concerns. Because pica levels in the ignore condition were consistently higher than in the play condition, we cannot rule out that pica may have been reinforced by either minimal adult attention or by access to up to 30 s of automatic reinforcement (i.e., chewing inedible items). Additionally, graduate students conducted conditions under the supervision of doctoral-level BCBAs. This level of expertise may not be available in typical early childhood or educational contexts but highlights the need for skilled behavioral consultation in schools, particularly for young children. In addition to expertise, other resources (e.g., time, staff availability), which may not be available in typical settings, are required to conduct FAs and intervention. Finally, we did not teach Luke a replacement behavior (e.g., to request teacher attention) because we implemented an antecedent intervention designed to provide immediate reductions in pica; teaching replacement behaviors might have further improved outcomes. Additional limitations include (a) the relatively long session length, which may be perceived as unacceptable in some typical environments but was done to reduce the likelihood of variability due to reduced sampling; (b) possible decreasing trends during the low-effort conditions; (c) classification of effort without social validation (i.e., gathering and setting up additional playground materials might be considered high effort); and (d) using a 1-min interval for DRO procedures, which may not have been sufficiently dense given rates of pica during the initial FA.

Conclusion

Despite the aforementioned limitations, results of the current study suggest that researchers successfully used information from the FA to develop intervention procedures based on identified functions of the problem behaviors, and long-term use of the intervention indicate its acceptability to staff. The data provide support for the use of FAs to inform effective interventions for young children with pica. Our data regarding the utility of FA procedures conducted in typical early childhood settings are encouraging. Future research should continue to evaluate ways to involve and train early childhood staff to implement FAs and identify and implement function-based interventions.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

Jennifer R. Ledford declares she has no conflicts of interest. Erin E. Barton declares she has no conflicts of interest. Monica N. Rigor declares she has no conflicts of interest. Kristen C. Stankiewicz declares she has no conflicts of interest. Kate T. Chazin declares she has no conflicts of interest. Emilee R. Harbin declares she has no conflicts of interest. Abby L. Taylor declares she has no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Research Highlights

• Functional assessments were conducted in an inclusive childcare setting.

• Results suggested pica was maintained by access to adult attention.

• Function-based but lower effort (e.g., noncontinuous) interventions were not effective for reducing levels of pica.

• A high-effort intervention was required to reduce pica; teachers maintained continued use of this intervention.

References

- Ali Z. Pica in people with intellectual disability: a literature review of aetiology, epidemiology, and complications. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability. 2001;26:205–215. doi: 10.1080/13668250020054486. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Hayes SC. Alternating treatments design: one strategy for comparing the effects of two treatments in a single subject. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1979;12:199–210. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1979.12-199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown WH, Conroy MA. Social-emotional competence in young children with developmental delays. Journal of Early Intervention. 2011;33:310–320. doi: 10.1177/1053815111429969. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter S, Wheeler J, Mayton M. Pica: a review of recent assessment and treatment procedures. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities. 2004;39:346–358. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap G, Fox L. Function-based interventions for children with challenging behavior. Journal of Early Intervention. 2011;33:333–343. doi: 10.1177/1053815111429971. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McAdam DB, Sherman JA, Sheldon JB, Napolitano DA. Behavioral interventions to reduce the pica of persons with developmental disabilities. Behavior Modification. 2004;28:45–72. doi: 10.1177/0145445503259219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz A, Bartley L. Active implementation frameworks for program success. Zero to Three Journal. 2012;32:11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Tapp J. Procoder for digital video [Computer software] Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wasano LC, Borrero JC, Kohn CS. Brief report: a comparison of indirect versus experimental strategies for the assessment of pica. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2009;39:1582–1586. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0766-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DE, McAdam D. Assessment, behavioral treatment, and prevention of pica: clinical guidelines and recommendations for practitioners. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2012;33:2050–2057. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]