Abstract

Background and aims

The current randomized controlled trial tested whether there was benefit to providing an online gambling intervention and a separate self-help mental health intervention for anxiety and depression (i.e. MoodGYM) (G + MH), compared to only a gambling intervention (G only) among people with co-occurring gambling problems and mental health distress. The primary outcome of interest was improvement in gambling outcomes. Secondary analyses also tested for the impact of the combined intervention on depression and anxiety outcomes.

Methods

Participants who were concerned about their gambling were recruited to help evaluate an online intervention for gamblers. Those who met criteria for problem gambling were randomized to receive either the G only or the G + MH intervention. Participants were also assessed for current mental health distress at baseline, with three quarters (n = 214) reporting significant current distress and form the sample for this study. Participants were followed-up at 3- and 6-months to assess changes in gambling status, and improvements in depression and anxiety.

Results

Follow-up rates were poor (47% completed at least one follow-up). While there were significant reductions in gambling outcomes, as well as on measures of current depression and anxiety, there was no significant difference in outcomes between participants receiving the G only versus the G + MH intervention.

Discussion and conclusion

There does not appear to be a benefit to providing access to an additional online mental health intervention to our online gambling intervention, at least among participants who are concerned about their gambling.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.govNCT02800096; Registration date: June 14, 2016.

Keywords: Gambling, Co-occurring disorders, Randomized controlled trial, Internet intervention

Highlights

-

•

Explores the benefits of providing online mental health and gambling interventions to people seeking help for their gambling

-

•

Adding a mental health intervention to an online gambling intervention does not improve gambling or mental health outcomes

1. Introduction

Gambling problems cause the individual and society significant harm (Afifi et al., 2010). Many of those with gambling problems are interested in receiving help for their gambling concerns (Cunningham et al., 2008). However, the large majority do not seek formal help, whether due to a lack of availability, concerns over stigma, or a desire for self-reliance (Cunningham, 2005; Slutske, 2006; Suurvali et al., 2008; Suurvali et al., 2012). Rather than relying solely on face-to-face treatment and grassroots initiatives such as Gamblers Anonymous as the only options for accessing assistance, there is a need to develop alternative means of providing help in order to optimize the chances that people with gambling problems will access care.

The earlier research on self-help interventions for problem gambling involved the development and evaluation of self-help books and telephone helplines (Hodgins et al., 2007; Raylu et al., 2008). More recent efforts have involved Internet interventions and smartphone apps (Hodgins et al., 2013; Luquiens et al., 2016). However, there is only very limited published research in this area to-date. An additional challenge with providing help is that many people with gambling problems have other co-occurring mental health concerns (Bischof et al., 2013; Desai and Potenza, 2008; Kessler et al., 2008; Lorains et al., 2011; Martin et al., 2014; Petry et al., 2005). As with the provision of care in face-to-face settings, an issue of importance to the optimization of positive outcomes from gambling problems is whether interventions for gambling problems should be provided along with the simultaneous provision of help for mental health distress (Dowling et al., 2016; Geisner et al., 2014; Hodgins and el-Guebaly, 2010; Stea and Hodgins, 2011; Toneatto and Ladouceur, 2003; Wynn et al., 2014). A recent randomized controlled trial (RCT) has examined the impact of providing an online depression intervention to problem gamblers and found some improvement in both gambling and depression outcomes at an 8-week follow-up (Bucker et al., 2018).

The present trial sought to evaluate whether providing access to an evidence-based online intervention targeting depression and anxiety concurrently with an Internet intervention for gambling (G + MH) would lead to improved outcomes for problem gamblers with and without co-occurring mental health concerns as compared to just providing an online gambling intervention (G only). The mental health intervention selected was MoodGYM, a pre-existing self-help online intervention which has been shown to effectively reduce depression and anxiety symptoms at the population level (Twomey and O'Reilly, 2017). In brief, this online program uses cognitive behavioural therapy tools interactively via exercises, quizzes, workbooks, and summaries to primarily address anxiety and depression concerns. In addition, the intervention has been shown to have secondary benefits such as improving the general well-being among community users and reducing hazardous alcohol consumption (Powell et al., 2013), however its effectiveness and use among problem gamblers has, not to our knowledge, been evaluated.

The primary hypothesis was that, among problem gamblers with co-occurring mental health symptoms, providing access to the G + MH website would display significantly reduced gambling outcomes at three- and six-month follow-ups as compared to those provided access to the Gonly website. In addition, there were several other hypotheses in the trial (as outlined in the published protocol): that specifically targeted problem gamblers who did not meet cut-off scores for co-occurring mental health distress. However, because only a limited number of participants recruited for the trial did not meet criteria for co-occurring mental health distress (see Results), we will only report the findings from the primary hypothesis here (the results of all hypotheses can be found as part of the Final Report to the funder –available online) (Cunningham et al., 2018).

2. Methods

The study protocol is published elsewhere (Cunningham et al., 2016). Briefly, the trial was a double-blinded randomized controlled trial (RCT) with 3- and 6-month follow-ups.

2.1. Recruitment

The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Institutional Review Boards of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health and the Australian National University approved the study. All participants provided informed consent after being informed about the study. Participants were recruited using online advertisements (Facebook, Google AdWords) as well as a series of offline methods (newspaper, bus advertisements, radio advertisements). While the primary target of recruitment was participants from Manitoba (due to funding agency requirements), online advertisements were also targeted across Canada. The advertisement targeted participants who were concerned about their gambling and were interested in participating in a study that provided online help for their gambling. Recruitment ads that did not restrict word counts also clarified that the trial was designed for gamblers to help evaluate online materials for problem gamblers. Prospective participants who responded to the advertisement completed a brief eligibility survey asking the participant's age and the Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI) (Ferris and Wynne, 2001). Inclusion criteria were being 18 or older, and having a PGSI score of 3 or more.

2.2. Randomization, experimental conditions

Potential participants who met inclusion criteria were provided with an online consent form and were asked for their email address as indication that they consented to participate in the research. These prospective participants were then sent an email that contained a link to complete the remainder of the baseline survey. After completing this survey, prospective participants were asked to log into the intervention portal. Those who logged into the portal were randomized to one of two groups (1:1 ratio). Randomization was automated and stratified by participant sex, age group, and prior use of treatment for gambling problems. All participants were followed-up at three- and six-month post-randomization using an online survey (an email invitation including a unique link was sent to each participant). In order to promote retention, participants completing each of the follow-ups were sent a $20 gift certificate from Amazon.ca (i.e., honorarium of up to $40 total). Research staff involved in the trial were not informed of respondents' group allocation during interventions or at follow-up.

2.2.1. Intervention groups

2.2.1.1. Gambling only group (G only)

The online intervention was an adaptation of the Hodgins et al. self-help booklets for problem gambling (Hodgins and Makarchuk, 2002). These booklets have been subjected to a series of RCTs demonstrating their efficacy (Diskin and Hodgins, 2009; Hodgins et al., 2009; Hodgins et al., 2001). In addition, the booklets have been successfully translated into an online format previously (Hodgins et al., 2013). The content of the booklets (and the website) relies heavily on the tools developed in cognitive behavioural therapy and leads the participant through choosing a goal, making a change, and preventing relapse.

2.2.1.2. Gambling plus Mental Health group (G ± MH)

In addition to the G only online intervention, participants in the G + MH group were also provided access to MoodGYM, an extensively evaluated Internet intervention for mental health distress targeting both depression and anxiety (Christensen et al., 2004; Griffiths et al., 2004; Powell et al., 2013). For these participants, the G and MH interventions were both provided concurrently on their intervention portal home page as two different sets of modules that could be completed at the individual's leisure. Since participants were not recruited for an anxiety and/or depression study, further information for why they were given access to MoodGYM was not provided. Furthermore, while the program's main focus is to target depression and anxiety symptoms, it can and has been used by community samples for managing general psychological distress as noted by the developers (Powell et al., 2013).

2.3. Sample size estimate

As there was no direct evidence to inform a power analysis to test the proposed hypotheses, the estimated sample size was based on the work of Hodgins et al. evaluating self-help booklets (Hodgins et al., 2009; Hodgins et al., 2001). Using the conventions of a two-tailed test with an alpha of 0.05, a power of 0.80, and correlations between baseline and follow-up assessment measures of 0.5, a sample size of 112 participants per group (G-only and G + MH) was needed in order to detect a differential reduction of 2 gambling days per month between groups. A change of <2 gambling days may not be clinically significant. A 20% loss to follow-up by the 6-month follow-up was allowed for, resulting in a planned sample size of 280 participants.

2.4. Data analysis

2.4.1. Outcome variables

Following Hodgins et al. (2013), the primary outcome variables were number of days gambled in the past 30 days, and a past 3-month version of the NORC DSM-IV Screen for Gambling Problems (NODS) which indicates DSM-IV gambling severity (Toce-Gerstein and Volberg, 2004; Wulfert et al., 2005). Secondary outcomes were the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; past 2 weeks) to assess current depression (a score of 10 or more indicates moderate depression) (Kroenke et al., 2001) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7; current experience) was used to assess anxiety (a score of 10 or more indicates moderate anxiety) (Spitzer et al., 2006).

2.4.2. Baseline and follow-up assessments

Participants completed the PGSI (past 12 months) to assess severity of problem gambling. In addition to the outcome variables assessing gambling, the Kessler Distress Scale (K-10) was used to measure current mental health distress (Brooks et al., 2006; Kessler et al., 2002), with a cut-off score of 22 or more indicating current mental health distress. Prior treatment access (e.g. counselling, gamblers anonymous, helplines, self-help) was assessed using a comprehensive set of 10 yes/no items employed in previous research (Hodgins et al., 2009; Hodgins et al., 2001). Finally, demographic characteristics were also assessed. The three- and six-month follow-up surveys contained the same items using a past 3-month timeframe were appropriate (with the exception of demographic variables, which were not repeated).

2.4.3. Analysis plan

Bivariate analyses of baseline demographic and gambling characteristics were conducted. The analysis of the primary and secondary outcome variables employed mixed effect repeated measures models – each examining the fixed effect of time, intervention, and the time by intervention interaction. Missing data were estimated using a maximum likelihood approach. If any baseline characteristics (see Table 1) were found to be significantly different between intervention groups they were to be added to the mixed effect models as covariates.

Table 1.

Differences between G-only and G + MH interventions on baseline demographic and clinical characteristics for gamblers with co-occurring mental health distress.

| Variable | Intervention |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gambling intervention only (n = 102) |

Gambling + MH (n = 112) |

||

| Age, mean years (SD) | 40.2 (12.9) | 40.7 (12.7) | 0.777 |

| Males, % (n) | 42.2 (43) | 43.8 (49) | 0.814 |

| Some post-secondary or greater, % (n) | 62.7 (64) | 51.8 (58) | 0.109 |

| Married/common law, % (n) | 51.0 (52) | 50.9 (57) | 0.990 |

| Full/part-time employed, % (n) | 67.6 (69) | 70.5 (79) | 0.648 |

| Personal income >$30,000, % (n) | 72.0 (72) | 70.9 (78) | 0.861 |

| PGSI, mean (SD) | 16.7 (5.8) | 17.5 (5.4) | 0.280 |

| NODS, mean (SD) | 7.1 (2.3) | 7.0 (2.3) | 0.842 |

| Days gambled in last 30, mean (SD) | 13.6 (7.3) | 13.1 (8.2) | 0.644 |

| Ever attended formal treatment, % (n) | 37.3 (38) | 37.5 (42) | 0.970 |

| PHQ-9, mean (SD) | 14.4 (6.3) | 14.8 (6.4) | 0.643 |

| GAD-7, mean (SD) | 11.1 (5.7) | 11.9 (5.8) | 0.317 |

Note: Group differences were computed using chi-squares and t-tests.

PGSI; Problem Gambling Severity Index.

NODS; NORC DSM-IV Screen for past 3 month Gambling Problems.

PHQ-9; Patient Health Questionnaire.

GAD-7; Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale.

3. Results

Overall, a total of 386 participants met eligibility criteria and were screened into the study. Of those, 284 verified their email address and completed the baseline questionnaire thus enrolling into the study. Due to a programming error, one participant was not randomized at baseline and did not receive an intervention, therefore reducing the final sample to 283 participants. Of these participants, 75.6% (n = 214) scored 22 or above on the K-10, indicating the co-occurrence of clinically significant mental health symptoms. This high occurrence of clinically significant mental health symptoms in a general sample only recruited for gambling concerns did not allow meaningful comparisons to be made to those participants without co-occurring mental health concerns, as was originally proposed in the protocol. Participants who scored <22 on the K-10 were randomized, received access to the interventions, and the appropriate honourariums for follow-up, however, their results were not considered in these analyses. Complete results are available online as part of the Final Report to the funder (Cunningham et al., 2018).

Table 1 displays bivariate comparisons of demographic and gambling characteristics for the 214 participants with co-occurring mental health symptoms between those in the G only condition versus those in the G + MH condition and found no significant differences (p > 0.05) between conditions. A consort chart is provided in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Consort chart.

Of the 214 participants, the mean (SD) PGSI score was 17.2 (5.6), with 95.8% (205) meeting a score of 8 of more on the PGSI (indicating high risk gambling with a substantial level of gambling related problems). The most common types of gambling endorsed by participants as causing them problems were video lottery terminals (58.9%), slot machines (52.8%), instant or scratch tickets (27.6%), tables games in a casino (25.2%), and lottery tickets (19.6%) (video lottery terminals and slot machines are distinct forms of gambling which can be located in different venues, thus are reported separately). A total of 37.4% stated that they had ever attended formal treatment for their gambling concerns. Baseline scores on the PHQ-9 indicating current depression (Mean [SD] of 14.6 [6.3]) and the GAD-7 indicating current anxiety (Mean [SD] of 11.5 [5.7]) confirmed that the sample had significant co-occurring mental health symptoms.

The attrition rate was high, with 47.2% completing at least one follow-up (38.8% completed the 3-month follow-up and 34.1% completed the 6-month follow-up). There were no significant differences in attrition rates between conditions (p > 0.05).

3.1. Impact of the added mental health intervention on improvements in gambling outcomes

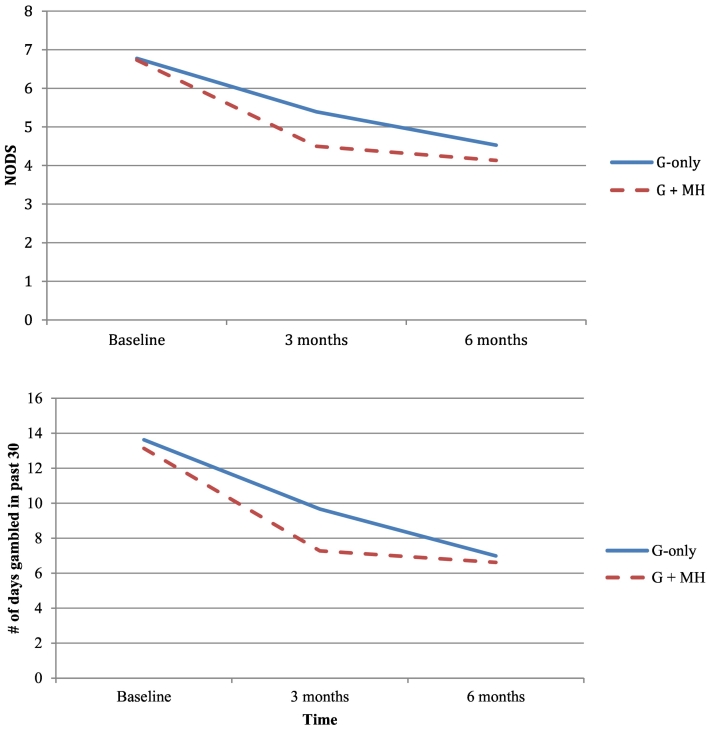

The primary hypothesis was tested using mixed effects models to investigate the effect of the G + MH intervention versus the G-only intervention on gambling changes over time (see Table 2). The two outcome measures were NODS scores and the number of days gambled in the past 30. Overall, both models revealed no significant differences across interventions in gambling at baseline, however both groups experienced significant reductions in their gambling severity (NODS; p ≤0.0001) and frequency (days gambled in the past 30; p ≤0.0001) over time. Neither model supported the hypothesis, as the reductions in gambling severity over time did not differ by intervention groups (NODS: p = 0.211; Number of days gambling in the past month: p = 0.373). Graphs illustrating the changes in gambling severity and gambling frequency over time across both the G-only and the G + MH interventions are presented in Fig. 2.

Table 2.

Mixed-effect model results of time, intervention, and time by intervention for gamblers with co-occurring mental health distress (N = 214).

| Effect | Estimate | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| NODS | |||

| Intercept | 6.73 | 29.74 | <0.0001 |

| Time (Reference: Baseline) | |||

| 3-months | −2.23 | −6.41 | <0.0001 |

| 6-months | −2.60 | −7.21 | <0.0001 |

| Intervention (Reference: G + MH) | |||

| G - only | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.897 |

| F | p | ||

| Time by intervention interaction | 1.57 | 0.211 | |

| Number of days gambled in the last 30 | |||

| Intercept | 13.13 | 18.57 | <0.0001 |

| Time (Reference: Baseline) | |||

| 3-months | −5.86 | −5.54 | <0.0001 |

| 6-months | −6.52 | −5.97 | <0.0001 |

| Intervention (Reference: G + MH) | |||

| G - only | 0.49 | 0.48 | 0.630 |

| F | p | ||

| Time by intervention interaction | 0.99 | 0.373 | |

NODS; NORC DSM-IV Screen for past 3 month Gambling Problems.

Fig. 2.

Gambling severity and frequency across time for gamblers with co-occurring mental health symptoms in the G-only and G + MH intervention (N = 214).

3.2. Impact of the added mental health intervention on improvement in mental health outcomes

In addition to examining changes in gambling over time, we also conducted secondary analyses to examine whether the provision of simultaneous access to online help for gambling problems and mental health symptoms had an impact on depression and anxiety symptoms over time. Two mixed-effects models (same procedure as with testing the primary hypothesis) were fitted to the data to examine these associations separately for depressive (PHQ-9) and anxiety (GAD-7) symptoms among gamblers While gamblers with co-occurring mental health symptoms experienced a significant decrease in both their depressive and anxiety symptoms over time, these decreases were not dependent on whether they received access to the mental health intervention in addition to the gambling intervention (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Mixed-effect model results of time, intervention, and time by intervention on depressive symptoms (PHQ-9) and gambling symptoms (GAD-7) for gamblers with co-occurring mental health distress (N = 214).

| Effect | Estimate | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| PHQ-9 | |||

| Intercept | 14.79 | 25.11 | <0.0001 |

| Time (Reference: Baseline) | |||

| 3-months | −4.31 | −5.27 | <0.0001 |

| 6-months | −5.55 | −6.58 | <0.0001 |

| Intervention (Reference: G + MH) | |||

| G - only | −0.40 | −0.47 | 0.638 |

| F | p | ||

| Time by intervention interaction | 1.25 | 0.288 | |

| GAD-7 | |||

| Intercept | 11.88 | 21.96 | <0.001 |

| Time (Reference: Baseline) | |||

| 3-months | −4.01 | −5.02 | <0.001 |

| 6-months | −4.39 | −5.31 | <0.001 |

| Intervention (Reference: G + MH) | |||

| G - only | −0.79 | −1.00 | 0.317 |

| F | p | ||

| Time by intervention interaction | 1.54 | 0.217 | |

Note: GAD-7; Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale.

PHQ-9; Personal Health Questionnaire.

3.3. Participants' use of interventions

Participants were encouraged to use the online interventions and received three reminder emails to login to the website, and a detailed record of the amount and type of use participants made of the G-only and the G + MH was kept. While both interventions provided access to a self-help online gambling tool comprised of four modules and a workbook, the G + MH intervention included additional access to an online mental health intervention (i.e., MoodGYM) which included an introductory component, five modules and a separate workbook. Furthermore, it is important to note that while participants were able to complete modules of the gambling self-help tool in any order, access to each module within MoodGYM is dependent on the completion of the preceding module. Overall, 46% (n = 98) of the whole sample accessed the gambling self-help tools, and 43% (n = 91) completed at least two modules. Conversely, of the 112 participants randomized to receive access to MoodGYM, only 25% (n = 28) accessed it and 7% (n = 8) completed at least two modules. Given the small proportion of participants accessing MoodGYM, it did not make sense to conduct analyses relating amount of use to outcome. The proportion of participants who used the self-help online gambling tools and MoodGYM, within each of the G-only and G + MH interventions is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Proportion of participants using different components of each online intervention among gamblers with co-occurring mental health distress (N = 214).

| Component of intervention used | % within intervention (n) |

|---|---|

| G – only intervention (N = 102) | |

| Self-help gambling tools | 51.0 (52) |

| G + MH intervention (N = 112) | |

| Self-help gambling tools only | 17.0 (19) |

| MoodGYM only | 0.1 (1) |

| Self-help gambling tools & MoodGYM | 24.1 (27) |

4. Discussion

Gambling problems and mental health concerns often co-occur (Bischof et al., 2013; Desai and Potenza, 2008; Kessler et al., 2008; Lorains et al., 2011; Martin et al., 2014; Petry et al., 2005). There are a number of unanswered questions regarding how best to provide help to people with these combined difficulties. The aim of this RCT was to determine whether there was benefit to adding access to an online intervention for mental health concerns to one for gambling. The prediction was that such a “one-stop shop” for people with combined concerns would lead to improved gambling outcomes as compared to providing just a gambling intervention. However, results from the current trial did not confirm this prediction. While there were large reductions in quantity of gambling in both groups, there was no clear evidence that participants garnered additional benefits from having access to a mental health intervention in addition to an online gambling intervention.

Secondary analyses were also conducted to test for any potential benefits of providing access to an online mental health intervention to the gambling intervention in order to reduce levels of depression and anxiety among this group with both gambling and mental health concerns (but who were concerned solely with their gambling). As with the gambling outcomes, while there were substantial reductions in self-reported measures of depression and anxiety in both groups, the additional provision of the mental health intervention did not appear to result in larger improvements in depression or anxiety as compared to just receiving the gambling intervention, as has generally been found in other gambling intervention trials (Ranta et al., 2018; Yakovenko and Hodgins, 2016). The online mental health intervention chosen for this trial, MoodGYM, has an extensive evidence base regarding its efficacy to promote improvements in anxiety and depression in a variety of different settings. As such, it is unlikely that the lack of findings were because MoodGYM is ineffective. A more likely explanation is that the particular circumstances of this trial - providing a mental health intervention to a group concerned about their gambling but who were unaware that they would also be offered help for mental health concerns - led to the lack of observed effects (i.e., participants were seeking help for their gambling and, in this context, were not motivated to access and use tools for mental health distress). This is the case, even though the participants reported significant mental health distress. Further, there was very limited use of the mental health intervention among those offered it, further emphasizing the lack of interest in these additional resources. It is possible that a more integrated gambling and mental health online intervention would result in more use of the mental health component. Or, a briefer mental health intervention might be more appropriate for the context such as its addition to a website that people are accessing because of gambling concerns.

There were a number of limitations in this trial. Primarily, the attrition rate was high as compared to other follow-up rates the authors of this paper have observed within previous gambling research (Cunningham et al., 2012; Hodgins et al., 2019), leading to the need for caution in interpreting the results. In addition, the trial itself could be regarded as underpowered because it might be more appropriate to expect small effect sizes rather than the medium effect size assumption that was employed in the power analysis. Finally, it is relevant to note that the gambling intervention has not demonstrated efficacy to reduce gambling in an online format (but has in a paper and pencil format) (Diskin and Hodgins, 2009; Hodgins, et al., 2019; Hodgins et al., 2009; Hodgins et al., 2001; Hodgins et al., 2013). Lastly, it should be noted that the authors anticipated only 50% of the sample of gamblers to meet cut-off scores for general psychological distress based on prevalence data. It is unknown why the high prevalence of psychological distress was observed, however it should be explored in future studies. However, despite these limitations, the pattern of results from this trial indicates that combining online interventions for gambling and mental health concerns might not be an effective means of providing additional help among gamblers who also have mental health concerns (or, at least, that the particular interventions employed in the current trial did not provide a combined additional benefit).

While the number of participants who had co-occurring gambling and mental health concerns was striking (even in a sample that was recruited solely because of their gambling concerns), we conclude that the additional provision of a mental health intervention to a website targeting gambling concerns does not appear to improve either gambling or mental health outcomes above that observed by providing the gambling intervention alone.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Manitoba Gambling Research Program of Manitoba Liquor and Lotteries; however, the findings and conclusions of this paper are those solely of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Manitoba Liquor and Lotteries. The funding body has no role or influence on the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript. This research was undertaken in part thanks to funding from the Canada Research Chairs program for support of Dr. Cunningham, the Canada Research Chair in Addictions. Support to CAMH for salary of scientists and infrastructure has been provided by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of the Ministry of Health and Long Term Care.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Afifi T.O., Cox B.J., Martens P.J., Sareen J., Enns M.W. Demographic and social variables associated with problem gambling among men and women in Canada. Psychiatry Res. 2010;178(2):395–400. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischof A., Meyer C., Bischof G., Kastirke N., John U., Rumpf H.J. Comorbid Axis I-disorders among subjects with pathological, problem, or at-risk gambling recruited from the general population in Germany: results of the PAGE study. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210(3):1065–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks R.T., Beard J., Steel Z. Factor structure and interpretation of the K10. Psychol. Assess. 2006;18(1):62–70. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.18.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucker L., Bierbrodt J., Hand I., Wittekind C., Moritz S. Effects of a depression-focused internet intervention in slot machine gamblers: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2018;13(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, H., Griffiths, K. M., & Jorm, A. F. (2004). Delivering interventions for depression by using the internet: randomised controlled trial. British Medical Journal, 328(7434), 265-268A. doi:Doi 10.1136/Bmj.37945.566632.Ee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cunningham J.A. Little use of treatment among problem gamblers. Psychiatr. Serv. 2005;56(8):1024–1025. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.8.1024-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham J.A., Hodgins D.C., Toneatto T. Problem gamblers' interest in self-help services. Psychiatr. Serv. 2008;59(6):695–696. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.6.695a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham J.A., Hodgins D.C., Toneatto T., Murphy M. A randomized controlled trial of a personalized feedback intervention for problem gamblers. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(2):e31586. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham J.A., Hodgins D.C., Bennett K., Bennett A., Talevski M., Mackenzie C.S., Hendershot C.S. Online interventions for problem gamblers with and without co-occurring mental health symptoms: protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:624. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3291-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham J.A., Hodgins D.C., Mackenzie C.S., Godinho A., Schell C., Kushnir V., Hendershot C.S. Retrieved from Winnipeg; Canada: 2018. Final Report: Online Interventions for Problem Gamblers With and without Co-occurring Mental Health Symptoms: Randomized Controlled Trial.https://www.manitobagamblingresearch.com/node/260 [Google Scholar]

- Desai R.A., Potenza M.N. Gender differences in the associations between past-year gambling problems and psychiatric disorders. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2008;43(3):173–183. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0283-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diskin K.M., Hodgins D.C. A randomized controlled trial of a single session motivational intervention for concerned gamblers. Behavioral Research and Therapy. 2009;47(5):382–388. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling N.A., Merkouris S.S., Lorains F.K. Interventions for comorbid problem gambling and psychiatric disorders: advancing a developing field of research. Addict. Behav. 2016;58:21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferris J., Wynne H. 2001. The Canadian Problem Gambling Index: Final Report. (Retrieved from) [Google Scholar]

- Geisner I.M., Bowen S., Lostutter T.W., Cronce J.M., Granato H., Larimer M.E. Gambling-related problems as a mediator between treatment and mental health with at-risk college student gamblers. J. Gambl. Stud. 2014;31:1005–1013. doi: 10.1007/s10899-014-9456-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths K.M., Christensen H., Jorm A.F., Evans K., Groves C. Effect of web-based depression literacy and cognitive-behavioural therapy interventions on stigmatising attitudes to depression - randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2004;185:342–349. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.4.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgins D.C., el-Guebaly N. The influence of substance dependence and mood disorders on outcome from pathological gambling: five-year follow-up. J. Gambl. Stud. 2010;26(1):117–127. doi: 10.1007/s10899-009-9137-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgins D.C., Makarchuk K. 2002. Becoming a Winner. Defeating Problem Gambling. (Retrieved from Edmonton) [Google Scholar]

- Hodgins D.C., Currie S.R., el-Guebaly N. Motivational enhancement and self-help treatments for problem gambling. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2001;69(1):50–57. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgins D.C., Currie S.R., el-Guebaly N., Diskin K.M. Does providing extended relapse prevention bibliotherapy to problem gamblers improve outcome? J. Gambl. Stud. 2007;23(1):41–54. doi: 10.1007/s10899-006-9045-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgins D.C., Currie S.R., Currie G., Fick G.H. Randomized trial of brief motivational treatments for pathological gamblers: more is not necessarily better. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2009;77(5):950–960. doi: 10.1037/a0016318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgins D.C., Fick G.H., Murray R., Cunningham J.A. Internet-based interventions for disordered gamblers: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial of online self-directed cognitive-behavioural motivational therapy. BMC Public Health. 2013;13 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgins D.C., Cunningham J.A., Murray R., Hagopian S. Online self-directed interventions for gambling disorder: Randomized controlled trial. J. Gambl. Stud. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s10899-019-09830-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R.C., Andrews G., Colpe L.J., Hiripi E., Mroczek D.K., Normand S.L.T., Walters E.E., Zaslavsky A.M. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol. Med. 2002;32(6):959–976. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R.C., Hwang I., LaBrie R., Petukhova M., Sampson N.A., Winters K.C., Shaffer H.J. DSM-IV pathological gambling in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychol. Med. 2008;38(9):1351–1360. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708002900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B.W. The PHQ-9 - validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorains F.K., Cowlishaw S., Thomas S.A. Prevalence of comorbid disorders in problem and pathological gambling: systematic review and meta-analysis of population surveys. Addiction. 2011;106(3):490–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luquiens A., Tanguy M.L., Lagadec M., Benyamina A., Aubin H.J., Reynaud M. The efficacy of three modalities of internet-based psychotherapy for non-treatment-seeking online problem gamblers: a randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016;18(2):e36. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin R.J., Usdan S., Cremeens J., Vail-Smith K. Disordered gambling and co-morbidity of psychiatric disorders among college students: an examination of problem drinking, anxiety and depression. J. Gambl. Stud. 2014;30(2):321–333. doi: 10.1007/s10899-013-9367-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry N.M., Stinson F.S., Grant B.F. Comorbidity of DSM-IV pathological gambling and psychiatric disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on alcohol and related conditions. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2005;66(5):564–574. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell J., Hamborg T., Stallard N., Burls A., McSorley J., Bennett K., Griffiths K.M., Christensen H. Effectiveness of a web-based cognitive-behavioral tool to improve mental well-being in the general population: randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2013;15(1):2–18. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranta J., Bellringer M., Garrett N., Abbott M. Can a brief telephone intervention for problem gambling help to reduce co-existing depression? A three-year prospective study in New Zealand. J. Gambl. Stud. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s10899-018-9783-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raylu N., Oei T.P.S., Loo J. The current status and future direction of self-help treatments for problem gamblers. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2008;28(8):1372–1385. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slutske W.S. Natural recovery and treatment-seeking in pathological gambling: results of two U.S. national surveys. Am. J. Psychiatr. 2006;163(2):297–302. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.2.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer R.L., Kroenke K., Williams J.B.W., Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder - the GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006;166(10):1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stea J.N., Hodgins D.C. 2011. A critical review of treatment approaches for gambling disorders. (Current drug abuse reviews) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suurvali H., Hodgins D.C., Toneatto T., Cunningham J.A. Treatment-seeking among Ontario problem gamblers: results of a population survey. Psychiatr. Serv. 2008;59:1343–1346. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.11.1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suurvali H., Hodgins D.C., Toneatto T., Cunningham J.A. Hesitation to seek gambling-related treatment among Ontario problem gamblers. J. Addict. Med. 2012;6(1):39–49. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3182307dbb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toce-Gerstein, M., & Volberg, R. A. (2004). The NODS-CLiP: A new brief screen for pathological gambling. Paper presented at the International Symposium on Problem Gambling and Co-Occurring Disorders, Mystic, CT. mhtml: http://www.gamblingproblem.org/presentations/Volberg.mht!Volberg_files/frame.htm.

- Toneatto T., Ladouceur R. Treatment of pathological gambling: a critical review of the literature. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2003;17(4):284–292. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.4.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twomey C., O'Reilly G. Effectiveness of a freely available computerised cognitive behavioural therapy programme (MoodGYM) for depression: meta-analysis. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2017;51(3):260–269. doi: 10.1177/0004867416656258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wulfert E., Hartley J., Lee M., Wang N., Franco C., Sodano R. Gambling screens: does shortening the time frame affect their psychometric properties. J. Gambl. Stud. 2005;21(4):521–536. doi: 10.1007/s10899-005-5561-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynn J., Hudyma A., Hauptman E., Houston T.N., Faragher J.M. Treatment of problem gambling: development, status, and future. Drugs and Alcohol Today. 2014;14(1):42–50. [Google Scholar]

- Yakovenko I., Hodgins D.C. Latest developments in treatment for disordered gambling: review and critical evaluation of outcome studies. Current Addictions Report. 2016;3:299–306. [Google Scholar]