Abstract

Emerging evidence indicates that cognitive deficits in Alzheimer's disease (AD) are associated with disruptions in brain network. Exploring alterations in the AD brain network is therefore of great importance for understanding and treating the disease. This study employs an integrative functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) – electroencephalography (EEG) analysis approach to explore dynamic, regional alterations in the AD-linked brain network. FNIRS and EEG data were simultaneously recorded from 14 participants (8 healthy controls and 6 patients with mild AD) during a digit verbal span task (DVST). FNIRS-based spatial constraints were used as priors for EEG source localization. Graph-based indices were then calculated from the reconstructed EEG sources to assess regional differences between the groups. Results show that patients with mild AD revealed weaker and suppressed cortical connectivity in the high alpha band and in beta band to the orbitofrontal and parietal regions. AD-induced brain networks, compared to the networks of age-matched healthy controls, were mainly characterized by lower degree, clustering coefficient at the frontal pole and medial orbitofrontal across all frequency ranges. Additionally, the AD group also consistently showed higher index values for these graph-based indices at the superior temporal sulcus. These findings not only validate the feasibility of utilizing the proposed integrated EEG-fNIRS analysis to better understand the spatiotemporal dynamics of brain activity, but also contribute to the development of network-based approaches for understanding the mechanisms that underlie the progression of AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, Brain network, EEG source imaging, Functional near-infrared spectroscopy, Graph theory

Highlights

-

•

Dynamic brain networks of healthy controls and patients with mild AD are documented via an integrative fNIRS-EEG approach.

-

•

FNIRS-based constraints are employed as spatial priors for EEG source localization.

-

•

Mild AD group reveals weaker connectivity to the orbitofrontal and parietal regions in high alpha band and beta band.

-

•

AD-linked brain networks are characterized by lower degree and clustering coefficient at the frontal area.

-

•

AD group also reveals higher index values for these graph-based indices at the superior temporal sulcus.

1. Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is an irreversible, chronic neurodegenerative brain disease that is typically characterized by progressive impairment of cognitive functions, including a marked degradation of memory (Kumar et al., 2015). In recent years, AD has been considered the most common form of dementia, afflicting about 5.7 million people in United States (Association, 2018). AD is physiologically characterized by the pathological presence of amyloid-beta (Aβ) and hyperphosphorylated tau proteins, as well as significant neurodegeneration and deficits within neurotransmitter systems (Cohen and Klunk, 2014; Palmqvist et al., 2015). These alterations often lead to abnormal cortical activity and connectivity that can be detected by noninvasive measurement techniques, such as electroencephalography (EEG), functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS).

EEG presents a number of advantages when exploring neural activity: it is non-invasive, inexpensive, clinically available, and features a very high temporal resolution (millisecond-level) (Li et al., 2017). By applying connectivity analyses to source-localized EEG signals, AD-linked alterations in regional connectivity have been identified (Canuet et al., 2012; Vecchio et al., 2014; Kabbara et al., 2018). In particular, several studies have reported abnormal functional connectivity in the alpha and beta band signals of AD patients (Canuet et al., 2012; Kabbara et al., 2018). Separately, Kabbara et al. have showed that AD networks are characterized by lower global information processing and higher local information processing than those of healthy, age-matched controls (Kabbara et al., 2018). Results also revealed a significant positive correlation between global efficiency, average clustering coefficient and vulnerability in AD network and corresponding Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores, which supports the feasibility of using EEG-based connectivity analyses to monitor the different stages of AD, or even preclinical AD (Hata et al., 2016).

A common technical challenge for EEG source localization is the ill-posed nature of the “inverse problem”; the number of variables that give rise to EEG signals vastly outnumbers the available measurements (He et al., 2018). Conventional source imaging analysis typically makes use of a pseudo-inversion to alleviate this issue (Hamalainen and Ilmoniemi, 1994). This solution, however, relies on a maximized likelihood estimation and consequently suffers from complex calculation and spatial imprecision. Attempts have therefore been made to overcome this challenge by combining EEG data with the results from other neuroimaging modalities, such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) (Nguyen et al., 2016). In general, traditional fMRI/EEG integration approaches, based on Wiener filtration or Bayesian methods (Schmidt et al., 1999; Dale et al., 2000; Phillips et al., 2002; Kajihara et al., 2004), use an fMRI-derived BOLD activation map as spatial prior information to constrain the source space for EEG localization. Mathematically, these constraints are imposed as a part of the source covariance matrix, wherein fMRI-active EEG sources are maintained while fMRI-inactive EEG sources are penalized (Liu et al., 1998; Babiloni et al., 2001; Liu et al., 2006). This produces source localization results with increased spatial precision and reduced error. Beyond this, we have also developed a Dynamic Brain Transition Network (DBTN) approach, which uses time-variant fMRI spatial constraints to optimize fMRI-EEG integration based on a hierarchical Bayesian model (Nguyen et al., 2016).

FMRI-EEG integration approaches achieve highly specific, accurate results. Unfortunately, fMRI techniques face some inherent limitations; fMRI is costly to perform, highly sensitivity to body-motion artifacts, and requires rigorous experimental design (Lee et al., 2013). These factors make fMRI data difficult to obtain and raise the potential for erroneous results or artifacts, limiting the clinical diagnostic potential of EEG-fMRI. To overcome these issues, physicians and researchers may opt to use functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) as supplement to EEG source localization. Functional near-infrared spectroscopy is a noninvasive optical imaging technique that typically utilizes two distinct wavelengths (between 600 and 1000 nm) to measure the changes in cortical oxy- and deoxy-hemoglobin concentrations that are coupled with neuronal metabolic activity (Scholkmann et al., 2014). As they rely on similar cerebrovascular dynamics, the results obtained by fNIRS are roughly analogous to those of fMRI (Ferrari and Quaresima, 2012; Boas et al., 2014), though fNIRS systems are portable and more resilient to motion artifacts. Furthermore, a recent study has tested and validated the use of fNIRS data as a spatial constraint to guide EEG source localization, achieving comparable results to fMRI-constrained EEG (Aihara et al., 2012).

In this study, a dynamic cortical connectivity mapping technique, based on an integrative analysis of concurrently recorded EEG and fNIRS signals, was developed and employed to identify the cortical network changes associated with AD. Specifically, concurrent EEG and fNIRS data were collected from both healthy controls and patients with mild AD (mAD) during a cognitive task. EEG source imaging was then performed using spatial priors derived from fNIRS information, and the reconstructed time-courses of cortical activity were used to generate connectivity networks for mild AD patients and healthy controls. Finally, the resultant networks were compared to identify AD-linked differences in cortical processing. It is hypothesized that the manifestation of AD, even at early stages, alters the neural circuitry of the brain when engaged in cognitive tasks, leading to “network biomarker” that can be identified using the proposed fNIRS-constraint EEG source localization technique (Kabbara et al., 2018).

2. Material and methods

2.1. Participants

Fourteen subjects were recruited as a part of this experiment, including six right-handed patients with mild AD (mAD, 72.5 ± 7.34 years, 2 M/4F) that were recruited from a local hospital and eight right-handed healthy volunteers (HC, 62.75 ± 8.21 years, 6 M/2F) that were recruited from the local community. Subjects were matched for age and gender, and had no history of cerebrovascular lesions or psychiatric disorders. No subject had previous experience with the experimental task. The mental state of each subject was examined using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) in Chinese, which is a 30-point questionnaire that provides a quantitative measure of cognitive status or impairment (Folstein et al., 1975), and scores were recorded. The experiment was approved by the Research Ethics Board of Nanjing Ruihaibo Medical Rehabilitation Center and performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Each subject was fully informed of the research purpose and methods, and provided written, informed consent prior to the start of the experiment.

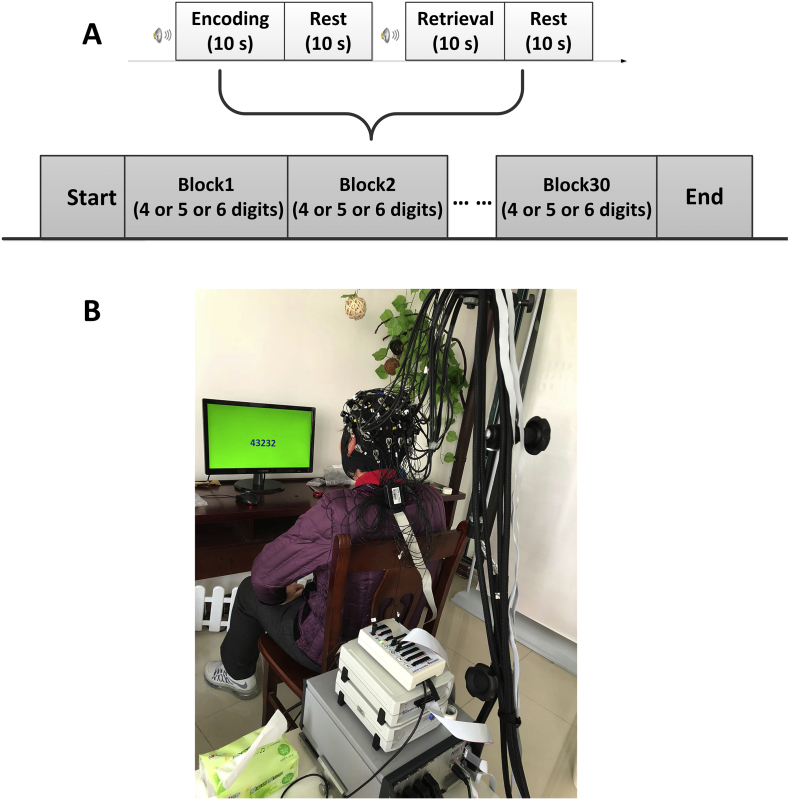

2.2. Experimental paradigm

A digit verbal span task was employed in this study, as shown in Fig. 1A. The task session consisted of 30 blocks, with each block broken down into 4× 10-s sections. Subjects first underwent an 10-s encoding task, in which they were asked to memorize a number sequence that displayed on a computer monitor 1.5 m in front of them (Fig. 1B). After encoding task, the number disappeared from the screen and the subjects were asked to stay relaxed for 10-s. This was followed by the 10-s “retrieval” task, wherein subjects were instructed to verbally recall the memorized number and results were recorded. The final 10 s in each block were set aside as a rest period. To remind the subjects of the beginning of tasks, a 1000 Hz-pure tone with 60 dB SPL-intensity was presented 1-s before each encoding and retrieval task and lasted for 100 ms through a small speaker placed beside the monitor. The background of the screen was set to green to make the subjects, especially the AD patients feel comfortable and relaxed during the experiment (Naz and Epps, 2004). Number sequences varied in length from 4 to 6 digits (each ranging from 1 to 9), and number lengths were varied every 10 blocks without replacement. All 30 sequences were unique and presented randomly to minimize subject-expectancy effects. Prior to the beginning of the experiment, subjects were seated in a comfortable chair and asked to relax for 3 min with eyes closed, during which baseline fNIRS signals were collected. To help the participants get familiar with the experimental procedures, each participant was allowed to practice the task for about 10 min before beginning the experiment.

Fig. 1.

Experimental design. (A) The digit verbal span task used in this study. (B) Illustration of experimental environment.

2.3. Data collection and preprocessing

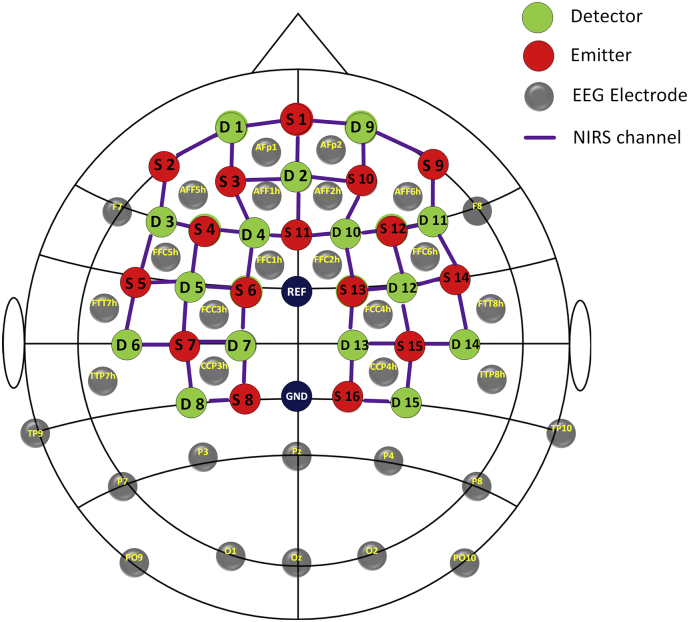

A concurrent EEG and fNIRS measurement setup was employed in this study. EEG data was collected using a BrainAmp DC EEG recording system (Brain Products GmbH, Germany). Electrode placement followed the international 10–20 convention for a 32-channel cap and signals were recorded at a sampling rate of 500 Hz.

A multi-channel NIRScout system (NIRx Medizintechnik GmbH, Germany) was used to measure the fNIRS signals at a sampling rate of 3.91 Hz. The inter-optode distance was fixed at 3 cm and a total of 46 measurement channels were distributed throughout the bilateral frontal and parietal cortices, according to the international 10–20 EEG placement system. The onset of each task was simultaneously recorded by the EEG amplifiers and fNIRS acquisition system, which was used for synchronizing two modalities during the data analysis. A schematic illustration of the EEG and fNIRS channel locations is provided in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The configuration of EEG electrodes and fNIRS optodes. Grey circles denote the EEG electrodes. Red circles denote fNIRS emitters, green circles denote fNIRS detectors, the purple lines and numbers are defined as fNIRS channels.

In this study, considering the EEG signal would be affected by the muscle movement when the subject is speaking in the retrieval task (Uriguen and Garcia-Zapirain, 2015), only the EEG and fNIRS signals recorded during the encoding task were used for analysis. EEG preprocessing was performed using BrainVision Analyzer 2.0 software (Brain Products, Germany). Data was first filtered from 0.5 Hz to 50 Hz, with an extra notch filter at 50 Hz to remove any residual powerline noise. Ocular artifact removal was then performed for each subject using independent component analysis (ICA) and the number of removed IC components was 3 and no >5 on average. Data was then re-referenced to a common-average reference and baseline correction was performed for each trial. Next, EEG data was segmented to form epochs that began 2 s before the onset of the encoding stage and ended 5 s after. Finally, artifact removal and trial rejection were performed through manual inspection. On average, fewer than 10% of the total number of trials were rejected per subject.

Every fNIRS channel was manually inspected and trials with large spikes were considered “noisy” and excluded from further analysis. On average, fewer than 10% of the total trials were rejected per subject. To process the fNIRS signals, a 4th order Butterworth band-pass filter, with cut-off frequencies of 0.01–0.2 Hz, was applied to remove artifacts such as cardiac interference (0.8 Hz) and respiration (0.2–0.3 Hz) (Zhang et al., 2005). The concentration changes of oxy- and deoxy-hemoglobin ([HbO] and [HbR]) were computed according to the Modified Beer-Lambert Law (nirsLAB, NIRx Medizintechnik GmbH, Germany) (Scholkmann et al., 2014). For each channel, fNIRS signal was baseline-corrected by subtracting the mean value of the resting-state signal from the signal during the active task. FNIRS signals from the encoding task period were then segmented from the onset of the task to 20 s afterwards.

2.4. Data analysis framework

2.4.1. The forward problem

In this study, a template brain model obtained from the MNI305 space was used as a common brain model for all subjects. The full segmentation and surface reconstruction of the MNI305 MRI volume was performed using the Freesurfer image analysis suite (publicly available at: http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/), resulting in the generation of a high-definition cortical layer and the brain, skull, and scalp boundary surfaces. These surfaces were then used to construct a three-compartment Boundary Element Method (BEM) model, with appropriate conductivity values assigned to each compartment using the MNE software (Gramfort et al., 2014). The high-density cortical layer mesh was downsampled to ~16,000 vertices per hemisphere and used as the source space, such that each vertex location corresponded to a dipole source oriented perpendicular to the surface. A lead-field matrix G was then computed via a forward calculation using the cortical source space, the 3-layer BEM model. EEG and fNIRS electrode positions were digitized and co-registered to the fiducial points on the template brain.

2.4.2. fNIRS spatial priors

The classical General Linear Model (GLM) (Calhoun et al., 2001; Worsley et al., 2002; Poline and Brett, 2012) was employed for the statistical analysis of preprocessed fNIRS data for each individual subject, and maps of significantly activated channels were obtained by contrasting the encoding task and baseline. Correction for multiple comparisons was performed using a cluster-based method (Woo et al., 2014) to limit the Family-wise error rate (FWER) to a maximum of 0.05. Channels with values in the fNIRS map above the p-value threshold (p-corrected > 0.05) were deemed insignificant and omitted, ensuring that only statistically significant voxels were used as constraints for the subsequent source imaging routine.

The fNIRS scalp activation map was normally projected and interpolated onto the cortical layer. Briefly, this procedure began by assigning the location of each fNIRS channel (defined as the mid-point between the emitter and detector) on the scalp layer. Next, the fNIRS scalp locations were normally projected onto the cortical layer, following the method described in (Okamoto et al., 2004). Finally, the fNIRS activation value at each channel was applied and interpolated to the sources on the cortical layer using method described in (Takeuchi et al., 2009).

In this study, individual fNIRS activation maps were divided into multiple sub-maps based on clusters of neighboring locations and cortical functional regions, allowing for greater spatial flexibility when applying the fNIRS information as a constraint (see more details in Section 3c). Specifically, active voxels were grouped into multiple sub-sets using a connected-component labeling technique (the Dulmage-Mendelsohn decomposition algorithm (Pothen and Fan, 1990)). Subsequently, each cortical patch was divided into smaller patches based on a predefined brain atlas to ensure that individual regions did not cover multiple functional brain regions. The DKT40 atlas was chosen in this protocol to define 68 functional regions of interest (ROIs) using automatic anatomical labeling (Fischl et al., 2004), which were used for source localization and connectivity analyses.

2.4.3. EEG source analysis with DBTN

Our recently developed spatiotemporal fMRI-constrained EEG source imaging approach (DBTN) was employed to perform source analysis, wherein each EEG epoch was analyzed using a sliding-window approach (Nguyen et al., 2016).

Very briefly, the linear mapping between sensor space and source space is described as:

| (1) |

where Y(twindow) ∈ ℝm×d represents the windowed EEG signals consisting of m channels and d measurement samples, G ∈ ℝm×s represents the lead field matrix, and J(twindow) ∈ ℝs×d represents the unknown source activity of s dipole sources in the source space for the corresponding time window. ԑ represents the noise component in the sensor space with its noise covariance matrix C, and R represents the source covariance matrix. The current density J can then be reconstructed according to the equation:

| (2) |

where the regularization parameter, λC, represents the trade-off between model accuracy and complexity, which is traditionally determined using the L-curve method (Hansen, 1992). The source covariance matrix R represents prior knowledge about the distribution of J. Following the framework for spatiotemporal fMRI-constrained EEG source imaging, R assumes the form of a weighted sum of multiple spatial priors, in which each prior is constructed as a sub-map of the fNIRS activation pattern.

| (3) |

R is defined as the sum of N covariance components weighted by an unknown hyperparameter λR. Each covariance component, Qi = qiqiT, is formed from a subset qi of the fNIRS map as explained above. The hyperparameters λR are estimated for each EEG window Y(twindow) using a Restricted Maximum Likelihood algorithm (see more details in (Nguyen et al., 2016)) and the corresponding current density J(twindow) is determined (eq. 2). In this study, the EEG time window was selected to be 200 ms long, with a 50% overlap, designed to provide a temporal resolution suited to the study of evoked response potentials. A time-course of cortical activity for each brain ROI was extracted by averaging the voxel activity within the region.

2.4.4. Functional connectivity analysis

The interaction between any pair-wise set of brain regions can be characterized by the Phase Lag Index (PLI) (Stam et al., 2007). In general, PLI measures the difference between the instantaneous phases of two time-series – this case, the activation time-course of the two ROIs. Weighted PLI extends the concept of PLI by weighting phase differences based on the magnitude of their lag (Vinck et al., 2011). The instantaneous phase of each time-series for every time point is computed by performing a Hilbert transform and isolating the resultant phase component. Given the instantaneous phase difference between the activities of two ROIs, ∆Φ, the wPLI is computed as

| (3) |

In graph-theory terms, each ROI forms a “node” within the graph and the wPLI values calculated between each pair of nodes form the “edges”. Following this approach, a weighted undirected graph was constructed from the obtained wPLI interaction matrix (Hatz et al., 2015).

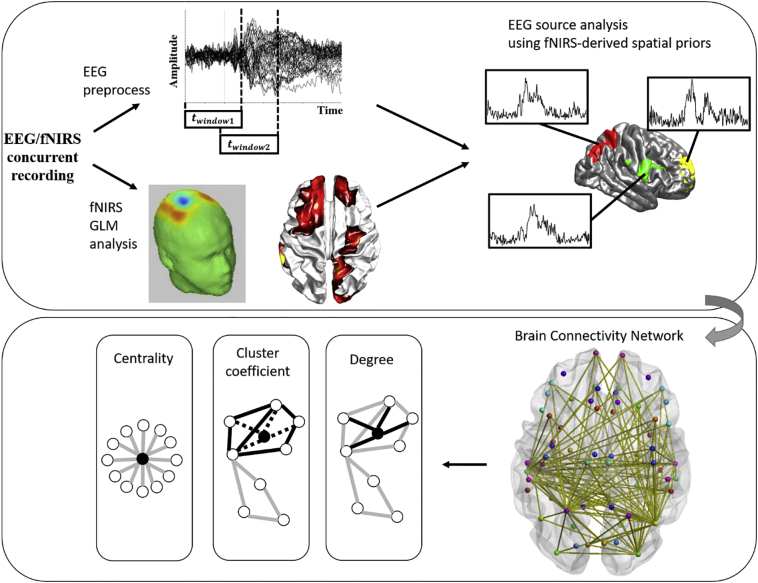

2.4.5. Graph-theory analysis

Based on the obtained weighted, undirected node-edge graph, several graph-theory measures were adopted to characterize the brain connectivity networks in healthy and mild AD patients. The metrics used in this study included degree, clustering coefficient, and centrality index. In general, the degree metric for a particular ROI reflects the number of connections that link the target ROI to the rest of the network. Clustering coefficient represents the ratio of connections that exist between a node and its nearest neighbors to the maximum number of possible connections. This serves as a summary of the local interactions between a particular ROI and its neighboring ROIs. Finally, the centrality index, called betweenness centrality, measures the number of “shortest paths” between the other node pairs that pass through a target node. Cortically, this indicates how influential the target region is as a hub within the brain network. Prior to the calculation of all graph measures, the weighted, undirected node-edge graph for each subject was thresholded by setting the 60% of the weakest edges as 0 to remove trivial connections. All graph measures were then computed using the Brain Connectivity Toolbox (Rubinov and Sporns, 2010). Fig. 3 illustrates the analysis process described above.

Fig. 3.

The overall schematic for EEG source analysis guided by fNRIS spatial priors and subsequent brain connectivity analysis.

Finally, to quantify the differences between healthy and AD networks in terms of graph-theory measures, including frequency and regional measures of degree, clustering coefficient, and centrality, statistical tests were performed using the Mann Whitney U Test also known as Rank-Sum Wilcoxon test.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic, behavior and clinical rating scores

The demographic information for all subjects, including age, gender, education, MMSE scores and performance in the cognitive task, are summarized in Table 1. There were no significant difference between healthy controls and MAD patients in terms of age (p = .072), gender (p = .119), education (p = .9). However, the patient group showed significantly lower scores on the MMSE (p < .001) and performed poorer in the digital verbal span task (p = .014) relative to healthy controls.

Table 1.

The demographic information of all subjects. The “*” indicated a significant difference between two groups. The “+” indicated the result was obtained via Chi-square test.

| Characteristic | HC (n = 8) | Mild AD (n = 6) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ages (years) | 62.75 ± 8.21 | 72.5 ± 7.34 | 0.072 |

| Gender (M/F) | 6 M/2F | 2 M/4F | 0.119+ |

| MMSE | 28.1 ± 1.1 | 19.7 ± 3.0 | <0.001* |

| Education (years) | 11 ± 2.51 | 11.17 ± 2.79 | 0.9 |

| Performance | 30 | 24 ± 5.97 | 0.014* |

3.2. EEG response to cognition task

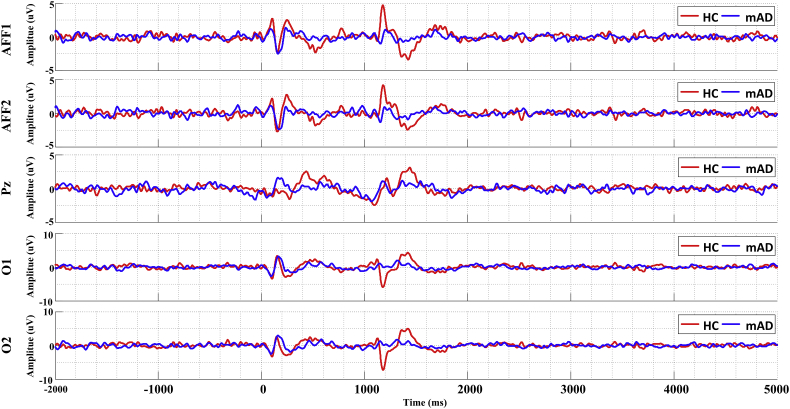

The grand-averaged EEG response to the encoding task in each channel was done by averaging all trials over all subjects in each group and shown in Fig. 4. Traces of EEG activity are presented for the frontal region (channel AFF1 and AFF2), parietal region (channel Pz), and the occipital region (channel O1 and O2).

Fig. 4.

EEG grand-average results for the HC group (red) and mAD group (blue), at the frontal channels (AFF1 and AFF2), parietal channel (Pz), and occipital channels (O1 and O2).

For both HC and mAD groups, brain responses to the auditory alert stimuli (t = 0 ms) were observed at around 200 ms. Minimal differences were observed between the responses of the two groups at this stage. Drastic differences started emerged ~1100 ms after the onset of the encoding task (t = 1100 ms), when the HC group showed a peak in activity at the frontal and occipital regions that was reduced in or absent from the mAD group. We performed two sample t-tests to assess the difference between two groups in terms of the mean amplitude of auditory-evoked response (0–400 ms) and mean amplitude of task-evoked response (1000–2000 ms). The results indicated that, for all selected channels, there was no significant difference in auditory responses (pcorrected > .05) but significant difference in task-evoked response between two groups (pcorrected < .05).

3.3. Current source analysis guided by fNIRS priors

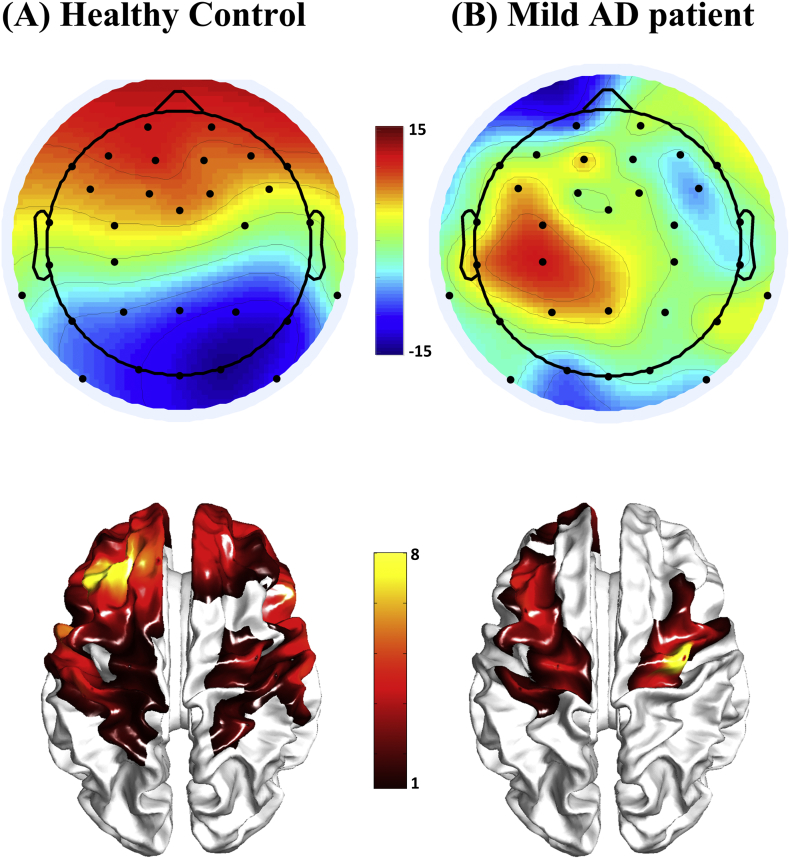

Fig. 5 shows the topographies of EEG signals and the corresponding fNIRS activation maps of a representative healthy subject and an AD patient obtained through GLM analysis and displayed on the cortical surface after undergoing the projection and interpolation procedure. It could be seen that the activation patterns obtained by two modalities were similar in healthy subject and patient. Specifically, the activation pattern of the HC showed an increase in activity at the frontal regions of the brain, and higher bilateral symmetry than that of the AD patient. Commonly activated regions included the bilateral premotor cortex, the orbitofrontal cortex, frontal pole, precentral gyrus and occipital lobe. In general, differences between the activated cortical regions of the healthy and AD brains pertained more to the frontal regions (frontal pole, orbital frontal).

Fig. 5.

Representative EEG topographies (1300 ms) and fNIRS activation maps for the healthy subject (A) and mild AD patient (B) during the encoding task. The fNIRS activation maps were projected and interpolated onto the cortical surface. Color scheme represents the t-statistic (pcorrected < .05).

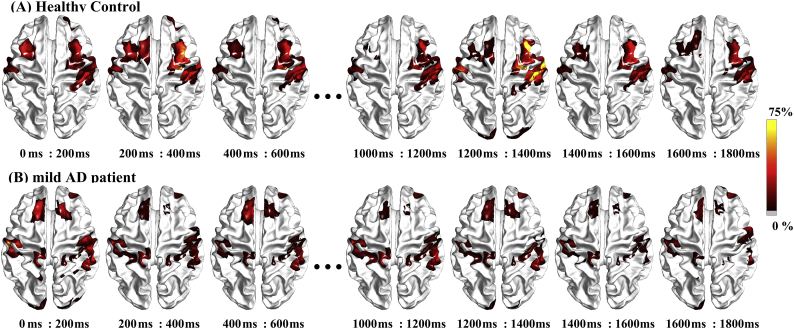

The spatiotemporal patterns of cortical activity associated with the memory-encoding task are depicted in Fig. 6. Overall, the activation pattern showed high similarity between the HC and AD patient groups. Major differences were observed at the activity of the frontal regions from 400 ms to 600 ms, 1200 ms to 1400 ms, and 1400 ms to 1600 ms. The detailed time-courses of cortical activity at the 68 regions of interest were used as a basis for subsequent brain connectivity analysis.

Fig. 6.

Source current activity for a (A) healthy control and (B) mild AD patient associated with the encoding task, averaged for every 200 ms time-step. Color scale reflects the reconstructed current density, normalized to the respective maximum.

3.4. Connectivity and graph theory analysis

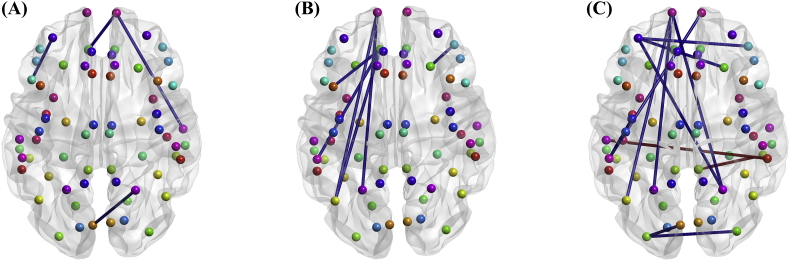

The connectivity analysis for each subject yielded a weighted undirected graph, and two-tailed t-testing was performed to identify which regional connections (edges) were different between the HC and mAD groups. Fig. 7 shows the significant differences in connectivity structure across all frequency bands between both groups. The mAD group consistently showed weaker cortical connectivity to the orbitofrontal and parietal regions. Specifically, weaker connections in the low alpha (8–10 Hz) and high alpha (10–13 Hz) frequency range (Fig. 7A and B) included: parietal ↔ frontal-pole, parietal ↔ orbital-frontal, and frontal ↔ superior-temporal. Connectivity within the beta frequency range (13–30 Hz) showed greater suppression in the mAD group than in the HC group, particularly in the case of inter-hemispheric interactions (Fig. 7C). Specific alterations in the beta range included: parietal ↔ frontal-pole, bilateral occipital lobes, and bilateral orbitofrontal lobes. Noticeably, the mAD group exhibited a bilateral interaction between left and right temporal regions that was significantly stronger than that observed in the HC group. Considering the results across frequency bands, it appears that inter-hemispheric connections were more likely to be weakened in AD patients.

Fig. 7.

Differences in brain connectivity structure between the HC and mAD groups (puncorrected < .05), reflected by wPLI measures in the low alpha band (A), high alpha band (B) and beta band (C). Edges in blue represent a weaker connection strength in the mAD group compared to HC group, and edges in red represent stronger connection strength in mAD group. Note that each dot denotes a node in the network, which is a predefined ROI in the cortex. The color scheme for nodes are arbitrary and used only to aid visualization.

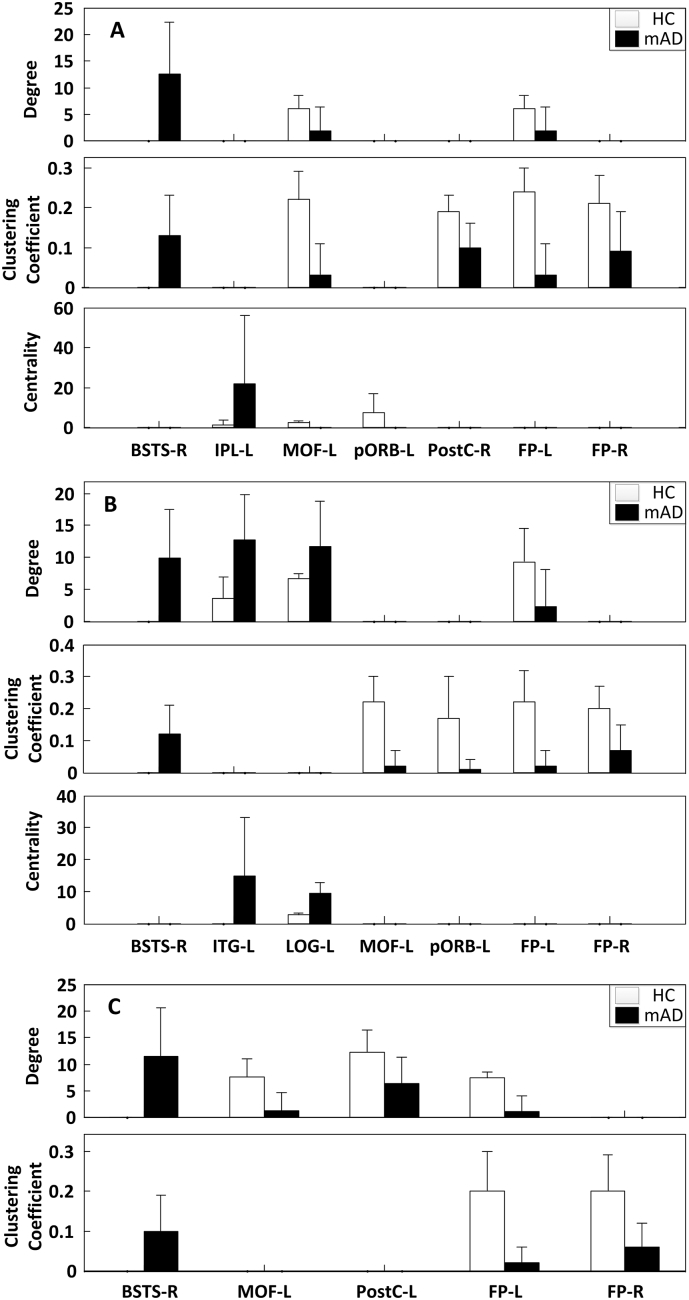

Graph theory was then applied to provide quantitative measure of the revealed network properties. Fig. 8 and the Table 2 show the degree, clustering coefficient, and centrality indices for the brain regions that showed statistically significant differences (puncorrected < .05) between the HC and mAD groups, particularly at frontopolar, orbitofrontal and temporal regions. Due to the small sample size and large number of nodes in this study, we didn't perform multiple comparison correction after the Mann Whitney U Test. As the results indicate, the HC group showed significantly higher index values for degree and clustering coefficient at the frontal pole (FP), medial-orbitofrontal (MOF), and postcentral (PostC) cortices, which were consistent across all frequency ranges. In contrast, the mAD group showed higher degree and clustering coefficient at the superior temporal sulcus (BSTS) across all frequency bands. Significant difference in centrality between two groups was only seen in alpha band, with HC group revealed higher centrality at medial-orbitofrontal (MOF) and pars orbitalis (pORB) in low alpha band and lower index values at inferior parietal (IPL), inferior temporal (ITG) and lateral occipital (LOG) areas in high alpha band. Interestingly, the regional differences regarding graph measures between two groups were more prominent in the left hemisphere (Fig. 8 and Table 2).

Fig. 8.

Regional graph theory measures for the connectivity networks of the HC (blue) and mAD groups (orange). Only regions revealed significant difference between two groups are shown for low alpha band (A), high alpha band (B) and beta band (C) (puncorrected < .05). BSTS: bankssts; IPL: inferior parietal; MOF: medial orbitofrontal; pORB: pars orbitalis; PostC: postcentral; FP: frontal pole; ITG: inferior temporal; LOG: lateral occipital; L: left hemisphere; R: right hemisphere.

Table 2.

Summary of differences among graph measures between healthy and AD networks in different frequency bands. BSTS: bankssts; IPL: inferior parietal; MOF: medial orbitofrontal; pORB: pars orbitalis; PostC: postcentral; FP: frontal pole; ITG: inferior temporal; LOG: lateral occipital; L: left hemisphere; R: right hemisphere.

| Index | Low alpha | High alpha | Beta | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Degree | Regions | p-Value | Regions | p-Value | Regions | p-Value |

| BSTS-R | 0.026 | BSTS-R | 0.026 | BSTS-R | 0.026 | |

| MOF-L | 0.048 | ITG-L | 0.013 | MOF-L | 0.017 | |

| FP-L | 0.048 | LOG-L | 0.022 | PostC_L | 0.048 | |

| FP-L | 0.043 | FP-L | 0.017 | |||

| Clustering coefficient | BSTS-R | 0.026 | BSTS-R | 0.026 | BSTS-R | 0.026 |

| MOF-L | 0.013 | MOF-L | 0.004 | FP-L | 0.013 | |

| PostC_R | 0.009 | pORB-L | 0.030 | FP-R | 0.030 | |

| FP-L | 0.009 | FP-L | 0.009 | |||

| FP-R | 0.047 | FP-R | 0.047 | |||

| Centrality | IPL-L | 0.017 | ITG-L | 0.004 | ||

| MOF-L | 0.004 | LOG-L | 0.030 | |||

| pORB-L | 0.030 | |||||

4. Discussion

Alzheimer's disease, as a form of dementia, presents with a number of cognitive symptoms that disrupt daily life. AD-linked impairments can be complex in nature and typically show progressive deterioration over the course of the disease. While the exact mechanisms that give rise to AD symptoms remain largely unknown, new imaging approaches have advanced our ability to noninvasively detect cortical activity and connections. The research presented here has sought to show the feasibility of DBTN-based EEG-fNIRS integrated imaging to explore cortical dynamics and potential neural biomarkers in AD. By capitalizing on the temporal resolution of EEG and spatial resolution of fNIRS, cortical functional connectivity was investigated in the low alpha, high alpha and beta frequency ranges. Secondary analysis was performed based on the principles of graph theory, which allowed regional network properties to be numerically quantified. Specific interest was paid to the measures of degree, clustering coefficient, and centrality, and results were compared to the networks derived from healthy subjects. The body of results presented here then provides both insight into the functional changes that accompany AD onset and evidence that regional graph-based measures are markedly changed in mild AD.

To perform a full, in-depth investigation of cortical dynamics, it was first necessary to simultaneously collect data from both EEG and fNIRS. Examination of the EEG results revealed two primary peaks of interest; one occurring at ~200–300 ms and a second arising at ~1100 ms (Fig. 4). Based on the experimental paradigm, it is believed that the first peak constitutes an auditory evoked potential, with possible P300 components, while the late peak is believed to represent cognitive task-related potential. Directly comparing how these peaks manifested in the HC and mAD groups presented a noteworthy contrast – the amplitude of the task-based peak (1100 ms) was greatly reduced in AD patients, while the amplitude of the auditory evoked potential (~300 ms) remained largely the same. This indicates that stereotypical, stimulus-linked ERPs are resilient to AD-linked cognitive deficits, while signals linked to encoding stimulus are diminished. These findings align with previous studies that have reported significantly reductions in the signal amplitude of MCI/AD patients when compared to healthy controls in cognitive tasks (Daffner et al., 2001; Saito et al., 2001), exhibiting the functional differences that accompany cognition impairment. In addition to superficial EEG signals, the reconstructed EEG source current activity, with spatial constraint from fNIRS signals, further uncovered a convincing spatiotemporal patterns of cortical activity associated with the memory-encoding task between healthy controls and AD patients. As demonstrated in Fig. 6, compared to healthy controls, AD patients revealed an altered distribution that featured more activity along the central sulcus and frontal area. The result presented here generally aligns with previous studies that identified activity in the middle frontal gyrus, dorsal lateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and inferior parietal cortex during digit verbal span task (Sun et al., 2005; Tian et al., 2014), validating the ability of the proposed fNIRS-EEG integration approach to characterize the spatiotemporal dynamics of AD-linked brain network.

Having effectively completed unimodal analyses, the DBTN framework was adapted and applied to investigate cortical dynamics and connectivity. Weighted phase lag index (wPLI) values were calculated between the time courses at each pair of ROIs, with results effectively indicating the different brain networks between groups. On the whole, the mAD group showed reduced functional connectivity when compared to their healthy counterparts (Fig. 7). The most apparent network alterations were observed in the high alpha and beta bands, with the low alpha connectivity map showing relatively fewer alterations (Fig. 7). Furthermore, changes showed that marked lateralization-significantly reduced connections were observed more often in the left hemisphere than right in high alpha and beta bands (Fig. 7B, C). In particular, the left frontal pole and orbitofrontal cortices appeared to show major reduced connections. The importance of these cortical regions has been suggested by previous literature as well (Johnson et al., 2000; Salat et al., 2001; Babiloni et al., 2009). For example, Johnson reported a significant positive correlation between atrophy and activation in left frontal area in AD patients, which may account for the cognition decline of AD patients (Johnson et al., 2000). Reductions in the bilateral connections of AD patients, such as the connections between the left and right frontal cortices in the beta band (Fig. 7C), provide additional evidence that hemispheric integration is reduced in AD cohort. Similar findings of hemispheric asymmetrical connectivity patterns were also previously reported (Sanz-Arigita et al., 2010; Kabbara et al., 2018). Finally, results from the AD patients found a pair of significantly increased wPLI values in the beta band. These increases were associated with the right temporal lobe and connected with the left temporal and right parietal areas, indicating that AD-linked cognitive impairments do not simply inhibit the global connectivity network. The unique nature of this connection may make it a specific point of interest as a potential biomarker. Previous studies have further identified two marked patterns of cortical properties in AD; temporal lobe atrophy and a reduction in the temporal and occipito-temporal beta power and mean frequency (Jelic et al., 2000; Visser et al., 2002; Pini et al., 2016). As wPLI characterizes the synchronization between regions (and stability thereof), it is reasonable to conclude that the relatively symmetrical degradation of the temporal lobe and the coincident reduction of beta frequency in AD may contribute to an increase in apparent wPLI values. With this in mind, monitoring the wPLI values between the temporal lobes or temporal-parietal lobes may provide advanced warning of the characteristic changes in AD. Furthermore, it should the noted that the interhemispheric nature of these interactions minimizes the chance for crosstalk and volume conduction, making the potential biomarker more resilient and accurate.

The direct measurement of wPLI provides a very detailed perspective of which cortical regions interact during the cognitive task and how these interactions vary in patients with AD. Unfortunately, the large amount of data from pure connectivity results makes it difficult to identify specific, meaningful differences between HC and the AD group. As a result, we applied graph theoretical measures to the identified connectivity structures and generated descriptive summary statistics for the identified networks, easing discrimination and highlighting potential biomarkers for diagnosis of AD. It should be noticed that small-worldness, computed from clustering coefficient and shortest path length of the network, is recently proposed to characterize global properties (high segregation and integration) of a brain network (Watts and Strogatz, 1998; Bassett and Bullmore, 2006, Bassett and Bullmore, 2017) and has been well-explored by previous AD studies using multiple neuroimaging techniques, such as fMRI and EEG (Toussaint et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2016). However, this fNIRS-EEG integration study solely focused on regional analysis using node-based measures to identify regional alterations in particular regions associated with AD, providing more regional information of the brain network compared to the global property conveyed by small-worldness. Node-based measures, including degree, clustering coefficient, and centrality were used as a part of this study, and each exhibited significant differences between the HC and AD groups across frequency ranges, as indicated in Fig. 8 and Table 2. Degree, which indicates the number of connections within a region, showed significant differences in a number of regions, particularly in the right superior temporal sulcus (BSTS-R, low alpha, high alpha and beta bands), left medial orbitofrontal (MOF-L, low alpha and beta bands), and left frontal pole (FP-L, low alpha, high alpha and beta bands) regions. Clustering coefficient showed a greater number of significant differences in all frequency ranges, particularly in the bilateral frontal pole (FP-L and FP-R) and right superior temporal sulcus (BSTS-R). Frequency-specific differences in clustering coefficient were found in the left medial orbitofrontal (MOF-L, low alpha and high alpha), right postcentral (PostC-R) and left pars orbitalis (pORB-L, beta) regions. Finally, centrality showed the most lateralized significance, including differences in the left inferior parietal, medial orbitofrontal, pars orbitalis, inferior temporal and lateral occipital areas within alpha band. Notably, centrality in the low and high alpha bands appeared to be increased in parietal, occipital, and temporal locations, areas that did not show significance in any other comparisons. These results indicate the potential of EEG-fNIRS-based neural biomarkers for the early characterization of AD, with regional indices appearing to be particularly impacted by cognitive decline. In particular, the left frontopolar regions showed significant decreases for degree and clustering coefficient in each frequency band, highlighting it as a particular region with discriminatory potential. On the contrary, the right superior temporal sulcus showed significant increases for these two measures in the each frequency band, making them potential markers of interest as well. These results reinforce the findings that can be observed from synchronization index (such as wPLI) measurements alone (Stam et al., 2009; Engels et al., 2015) and evidence a fundamental shift in network structure as hubs of activity transition from frontal to temporal locations over the course of AD onset. While these studies have focused largely on AD-linked changes within the default mode network, the present feasibility study has focused on cortical networks activated during a memory-based task. Considering that memory deficit is a defining characteristic of AD and that the prefrontal cortices are heavily implicated in memory processing, the regional alterations observed here are considered reasonable and evince the capability of integrated EEG-fNIRS approach in the detection of task-induced network changes.

Though this research has effectively used EEG-fNIRS to uncover potentially impactful dynamics of activity, there are several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the source localization here was performed using a generic head template with default electrode locations. Although the generic model still features a realistic anatomy, the lack of subject-specificity blinds the current method to individual differences in anatomy or cap setup. Considering this, it would be useful for future research to obtain anatomical MRI for the subject, which can be used to customize the model and forward calculation. Second, the fNIRS setup for this study was not able to provide full coverage due to a limited number of optodes. To minimize the effect of insufficient coverage, the cap setup here was designed to cover key regions of interest, and the proposed fNIRS-EEG integration approach was previously demonstrated to be highly robust against “false-positive prior” (i.e. active regions in fNIRS but not in EEG) and “missing prior” (i.e. missing regions from fNIRS activation map but active in EEG) as described in detailed in (Aihara et al., 2012). However, we acknowledge that gaps in coverage may still limit the prior information of fNIRS and reduce source localization accuracy, it is therefore suggested that future research utilize a setup with full coverage when possible. Finally, this study focused solely on evaluating the feasibility of utilizing fNIRS-EEG integration approach to explore dynamic alterations in the AD-linked brain network compared to healthy population. The preliminary results, though achieved based on the limited sample size, are believed to have provided sufficient evidence to support our feasibility evaluation. When attempting early detection of AD, however, it will be important to differentiate between each of these pathological conditions, including MCI or preclinical stage of AD that contribute to the development of AD. It will then be necessary to expand subject base and population in the future if true, defining neural biomarkers are to be obtained.

5. Conclusion

The complimentary properties and easy application of EEG and fNIRS has led to a significant research focus on their multimodal combination. This paper presents a feasibility study for the integration of EEG and fNIRS, using a spatiotemporally accurate integration method first established in EEG-fMRI to explore the alterations of AD networks compared to healthy controls. Following this approach, variations in regional connectivity were assessed and used to uncover frequency-linked differences between healthy controls and mild AD patients. Graph theory measures were then applied and a number of regional and frequency-specific features were identified. While more verifications will be necessary, this study has shown the potential for the inexpensive and portable assessment of possible AD neural biomarkers that are associated with brain connectivity network. With further research and definition, technique proposed in this paper may advance the detection and treatment of AD, improving outcomes and reducing costs for both individuals and healthcare providers.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the University of Houston.

Declaration/conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

References

- Aihara T., Takeda Y., Takeda K., Yasuda W., Sato T., Otaka Y. Cortical current source estimation from electroencephalography in combination with near-infrared spectroscopy as a hierarchical prior. NeuroImage. 2012;59(4):4006–4021. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association, A.S 2018 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(3):367–429. [Google Scholar]

- Babiloni F., Carducci F., Cincotti F., Del Gratta C., Pizzella V., Romani G.L. Linear inverse source estimate of combined EEG and MEG data related to voluntary movements. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2001;14(4):197–209. doi: 10.1002/hbm.1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babiloni C., Frisoni G.B., Pievani M., Vecchio F., Lizio R., Buttiglione M. Hippocampal volume and cortical sources of EEG alpha rhythms in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease. NeuroImage. 2009;44(1):123–135. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett D.S., Bullmore E.T. Small-world brain networks. Neuroscientist. 2006;12(6):512–523. doi: 10.1177/1073858406293182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett D.S., Bullmore E.T. Small-world brain networks revisited. Neuroscientist. 2017;23(5):499–516. doi: 10.1177/1073858416667720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boas D.A., Elwell C.E., Ferrari M., Taga G. Twenty years of functional near-infrared spectroscopy: introduction for the special issue. NeuroImage. 2014;85:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun V.D., Adali T., McGinty V.B., Pekar J.J., Watson T.D., Pearlson G.D. fMRI activation in a visual-perception task: network of areas detected using the general linear model and independent components analysis. NeuroImage. 2001;14(5):1080–1088. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canuet L., Tellado I., Couceiro V., Fraile C., Fernandez-Novoa L., Ishii R. Resting-state network disruption and APOE genotype in Alzheimer's disease: a lagged functional connectivity study. PLoS One. 2012;7(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen A.D., Klunk W.E. Early detection of Alzheimer's disease using PiB and FDG PET. Neurobiol. Dis. 2014;72:117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daffner K.R., Rentz D.M., Scinto L.F.M., Faust R., Budson A.E., Holcomb P.J. Pathophysiology underlying diminished attention to novel events in patients with early AD. Neurology. 2001;56(10):1377–1383. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.10.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale, A.M., Liu, A.K., Fischl, B.R., Buckner, R.L., Belliveau, J.W., Lewine, J.D., et al. (2000). Dynamic statistical parametric mapping: combining fMRI and MEG for high-resolution imaging of cortical activity. Neuron 26(1), 55–67. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81138–1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Engels M.M.A., Stam C.J., van der Flier W.M., Scheltens P., de Waal H., van Straaten E.C.W. Declining functional connectivity and changing hub locations in Alzheimer's disease: an EEG study. BMC Neurol. 2015;15 doi: 10.1186/s12883-015-0400-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari M., Quaresima V. A brief review on the history of human functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) development and fields of application. NeuroImage. 2012;63(2):921–935. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B., van der Kouwe A., Destrieux C., Halgren E., Segonne F., Salat D.H. Automatically parcellating the human cerebral cortex. Cereb. Cortex. 2004;14(1):11–22. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhg087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein M.F., Folstein S.E., McHugh P.R. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gramfort A., Luessi M., Larson E., Engemann D.A., Strohmeier D., Brodbeck C. MNE software for processing MEG and EEG data. NeuroImage. 2014;86:446–460. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamalainen M.S., Ilmoniemi R.J. Interpreting magnetic-fields of the brain - minimum norm estimates. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 1994;32(1):35–42. doi: 10.1007/BF02512476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen P.C. Analysis of discrete ill-posed problems by means of the L-curve. SIAM Rev. 1992;34(4):561–580. [Google Scholar]

- Hata M., Kazui H., Tanaka T., Ishii R., Canuet L., Pascual-Marqui R.D. Functional connectivity assessed by resting state EEG correlates with cognitive decline of Alzheimer's disease - an eLORETA study. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2016;127(2):1269–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2015.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatz F., Hardmeier M., Bousleiman H., Ruegg S., Schindler C., Fuhr P. Reliability of fully automated versus visually controlled pre- and post-processing of resting-state EEG. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2015;126(2):268–274. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2014.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He B., Sohrabpour A., Brown E., Liu Z.M. Electrophysiological source imaging: a noninvasive window to brain dynamics. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2018;20:171–196. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-062117-120853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelic V., Johansson S.E., Almkvist O., Shigeta M., Julin P., Nordberg A. Quantitative electroencephalography in mild cognitive impairment: longitudinal changes and possible prediction of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2000;21(4):533–540. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00153-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S.C., Saykin A.J., Baxter L.C., Flashman L.A., Santulli R.B., McAllister T.W. The relationship between fMRI activation and cerebral atrophy: comparison of normal aging and Alzheimer disease. NeuroImage. 2000;11(3):179–187. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1999.0530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabbara A., Eid H., El Falou W., Khalil M., Wendling F., Hassan M. Reduced integration and improved segregation of functional brain networks in Alzheimer's disease. J. Neural Eng. 2018;15(2) doi: 10.1088/1741-2552/aaaa76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajihara S., Ohtani Y., Goda N., Tanigawa M., Ejima Y., Toyama K. Wiener filter-magnetoencephalography of visual cortical activity. Brain Topogr. 2004;17(1):13–25. doi: 10.1023/b:brat.0000047333.10619.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Singh A., Ekavali A review on Alzheimer's disease pathophysiology and its management: an update. Pharmacol. Rep. 2015;67(2):195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.pharep.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M.H., Smyser C.D., Shimony J.S. Resting-state fMRI: a review of methods and clinical applications. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2013;34(10):1866–1872. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R.H., Potter T., Huang W.T., Zhang Y.C. Enhancing performance of a hybrid EEG-fNIRS system using channel selection and early temporal features. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2017;11 doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2017.00462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu A.K., Belliveau J.W., Dale A.M. Spatiotemporal imaging of human brain activity using functional MRI constrained magnetoencephalography data: Monte Carlo simulations. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95(15):8945–8950. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z.M., Ding L., He B. Integration of EEG/MEG with MRI and fMRI - High-resolution, multimodal neuroimaging. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. 2006;25(4):46–53. doi: 10.1109/memb.2006.1657787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naz K., Epps H. Relationship between color and emotion: a study of college students. Coll. Stud. J. 2004;38(3):396. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T., Potter T., Nguyen T., Karmonik C., Grossman R., Zhang Y.C. EEG source imaging guided by spatiotemporal specific fMRI: toward an understanding of dynamic cognitive processes. Neural Plast. 2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/4182483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto M., Dan H., Sakamoto K., Takeo K., Shimizu K., Kohno S. Three-dimensional probabilistic anatomical cranio-cerebral correlation via the international 10–20 system oriented for transcranial functional brain mapping. NeuroImage. 2004;21(1):99–111. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmqvist S., Zetterberg H., Mattsson N., Johansson P., Minthon L., Blennow K. Detailed comparison of amyloid PET and CSF biomarkers for identifying early Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2015;85(14):1240–1249. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips C., Rugg M.D., Friston K.J. Anatomically informed basis functions for EEG source localization: combining functional and anatomical constraints. NeuroImage. 2002;16(3):678–695. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pini L., Pievani M., Bocchetta M., Altomare D., Bosco P., Cavedo E. Brain atrophy in Alzheimer's disease and aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 2016;30:25–48. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poline J.B., Brett M. The general linear model and fMRI: does love last forever? NeuroImage. 2012;62(2):871–880. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.01.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pothen A., Fan C.-J. Computing the block triangular form of a sparse matrix. ACM Trans. Math. Softw. 1990;16(4):303–324. [Google Scholar]

- Rubinov M., Sporns O. Complex network measures of brain connectivity: Uses and interpretations. NeuroImage. 2010;52(3):1059–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito H., Yamazaki M., Matsuoka M., Matsumoto K., Numachi M., Yoshida S. Visual event-related potential in mild dementia of the Alzheimer's type. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2001;55(4):365–371. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1819.2001.00876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salat D.H., Kaye J.A., Janowsky J.S. Selective preservation and degeneration within the prefrontal cortex in aging and Alzheimer disease. Arch. Neurol. Chicago. 2001;58(9):1403–1408. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.9.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz-Arigita E.J., Schoonheim M.M., Damoiseaux J.S., Rombouts S.A.R.B., Maris E., Barkhof F. Loss of ‘small-world’ networks in Alzheimer's disease: graph analysis of fMRI resting-state functional connectivity. PLoS One. 2010;5(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt D.M., George J.S., Wood C.C. Bayesian inference applied to the electromagnetic inverse problem. Hum. Brain Mapp. 1999;7(3):195–212. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(1999)7:3<195::AID-HBM4>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholkmann F., Kleiser S., Metz A.J., Zimmermann R., Pavia J.M., Wolf U. A review on continuous wave functional near-infrared spectroscopy and imaging instrumentation and methodology. NeuroImage. 2014;85:6–27. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stam C.J., Nolte G., Daffertshofer A. Phase lag index: assessment of functional connectivity from multi channel EEG and MEG with diminished bias from common sources. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2007;28(11):1178–1193. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stam C.J., de Haan W., Daffertshofer A., Jones B.F., Manshanden I., van Walsum A.M.V. Graph theoretical analysis of magnetoencephalographic functional connectivity in Alzheimers disease. Brain. 2009;132:213–224. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X.W., Zhang X.C., Chen X.C., Zhang P., Bao M., Zhang D.R. Age-dependent brain activation during forward and backward digit recall revealed by fMRI. NeuroImage. 2005;26(1):36–47. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi M., Hori E., Takamoto K., Tran A.H., Satoru K., Ishikawa A. Brain cortical mapping by simultaneous recording of functional near infrared spectroscopy and electroencephalograms from the whole brain during right median nerve stimulation. Brain Topogr. 2009;22(3):197–214. doi: 10.1007/s10548-009-0109-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian F.H., Yennu A., Smith-Osborne A., Gonzalez-Lima F., North C.S., Liu H.L. Prefrontal responses to digit span memory phases in patients with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): a functional near infrared spectroscopy study. Neuroimage Clin. 2014;4:808–819. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toussaint P.J., Maiz S., Coynel D., Doyonc J., Messe A., de Souza L.C. Characteristics of the default mode functional connectivity in normal ageing and Alzheimer's disease using resting state fMRI with a combined approach of entropy-based and graph theoretical measurements. NeuroImage. 2014;101:778–786. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uriguen J.A., Garcia-Zapirain B. EEG artifact removal-state-of-the-art and guidelines. J. Neural Eng. 2015;12(3) doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/12/3/031001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vecchio F., Miraglia F., Marra C., Quaranta D., Vita M.G., Bramanti P. Human brain networks in cognitive decline: a graph theoretical analysis of cortical connectivity from EEG data. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2014;41(1):113–127. doi: 10.3233/JAD-132087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinck M., Oostenveld R., van Wingerden M., Battaglia F., Pennartz C.M.A. An improved index of phase-synchronization for electrophysiological data in the presence of volume-conduction, noise and sample-size bias. NeuroImage. 2011;55(4):1548–1565. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser P.J., Verhey F.R.J., Hofman P.A.M., Scheltens P., Jolles J. Medial temporal lobe atrophy predicts Alzheimer's disease in patients with minor cognitive impairment. J. Neurol. Neurosur. Ps. 2002;72(4):491–497. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.72.4.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.Q., Zhang M., Han Y., Song H.Q., Guo R.J., Li K.C. Differentially disrupted functional connectivity of the subregions of the amygdala in Alzheimer's disease. J. X-Ray Sci. Technol. 2016;24(2):329–342. doi: 10.3233/XST-160556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts D.J., Strogatz S.H. Collective dynamics of 'small-world' networks. Nature. 1998;393(6684):440–442. doi: 10.1038/30918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo C.W., Krishnan A., Wager T.D. Cluster-extent based thresholding in fMRI analyses: pitfalls and recommendations. NeuroImage. 2014;91:412–419. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.12.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worsley K.J., Liao C.H., Aston J., Petre V., Duncan G.H., Morales F. A general statistical analysis for fMRI data. NeuroImage. 2002;15(1):1–15. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.H., Brooks D.H., Franceschini M.A., Boas D.A. Eigenvector-based spatial filtering for reduction of physiological interference in diffuse optical imaging. J. Biomed. Opt. 2005;10(1) doi: 10.1117/1.1852552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]