The intestinal epithelium is a highly proliferative tissue comprising several differentiated cell types that originate from multipotent, self-renewing intestinal stem cells. In 1974, Cheng and Leblond1 described crypt-based columnar cells (CBCs), which are self-renewing stem cells that are now thought to fuel day-to-day replenishment of cells within the intestinal epithelium. CBCs, identified by Lgr5 expression, are highly proliferative but are sensitive to damaging insults. Potten2 first identified label-retaining cells at the +4 crypt position as reserve stem cells that can be mobilized in response to damage to CBCs. Thus, evidence has emerged that after elimination or damage to Lgr5+ stem cells, distinct populations of quiescent (eg, Bmi1-, mTert-, Hopx-, or Lrig1-expressing) stem cells can regenerate the appropriate stem and differentiated cell compartments. However, recent studies have supported the concept that differentiated and/or differentiating progenitor cells can regain stem cell abilities to regenerate the entire epithelium in response to various insults.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 In this issue of Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Jones et al8 provide evidence that differentiated protein-secreting cells possess the plasticity to regenerate epithelial cell lineages after severe injury.

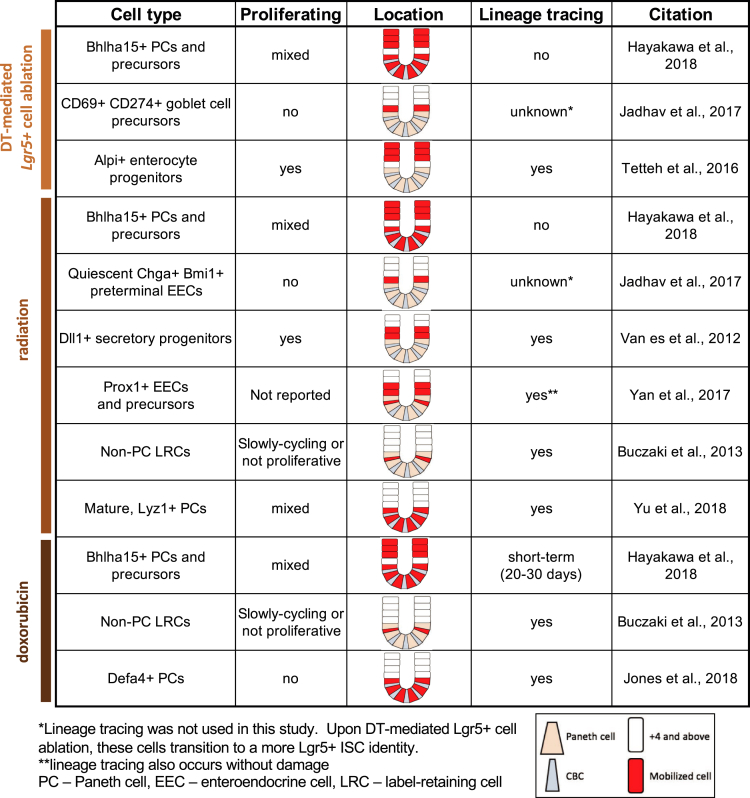

Many of the studies analyzing stem cell function in regeneration use a common set of damage stimuli, including doxorubicin, radiation, and diphtheria toxin (DT)-mediated ablation of Lgr5DTR-expressing CBCs, which differ in both severity and specificity. In turn, the population of mobilized cells and their efficiency in replenishing entire crypts differ in different damage contexts. Among the 3 insults, doxorubicin is most damaging because it induces cell death in all proliferating cells, including active CBCs and proliferating progenitor populations. Radiation is the next most damaging insult and results in cell-cycle arrest and limited apoptosis in fast-cycling CBCs, sparing slower-cycling progenitor populations in a dose-dependent fashion. The least damaging is DT-mediated ablation, which specifically targets Lgr5DTR-expressing CBCs. To interpret the results from the collection of recent studies, the type of damage must be taken into account. We have summarized the results from recent studies in Figure 1 which catalogs the cell type, proliferation status, and type of damage. In addition, Figure 1 shows whether lineage tracing was observed, which suggests dedifferentiation into a multipotent stem cell that can replenish all differentiated cell types in the epithelium. Interestingly, when the results are considered in the context of loss of particular cell populations owing to the type of insult, a distinct hierarchy of mobilized cell populations emerges. In the least damaging insult, DT-mediated Lgr5+ cell ablation, proliferative absorptive cell progenitors have been implicated as sources of stem cells to regenerate the epithelium. Upon irradiation, a more damaging insult that targets highly proliferative cells (including absorptive progenitors), the less proliferative secretory progenitors are mobilized to restore homeostasis. In this issue, Jones et al8 show that with an even more damaging doxorubicin insult, in which all progenitors are potentially eliminated, terminally differentiated Paneth cells are mobilized to replace lost stem cell functionality. Furthermore, Jones et al8 show that this regeneration occurs in a Notch-dependent manner.

Figure 1.

Recent lineage tracing studies from progenitor, precursor, and differentiated cells in response to damage. Large tan wedge, Paneth cell; narrow blue wedge, CBC; white rectangle, þ4 and above; red rectangle, mobilized cell. Lineage tracing was not used in this study by Jadhav et al.8 Upon DT-mediated Lgr5þ cell ablation, these cells transition to a more Lgr5þ ISC Q20 identity. Lineage tracing also occurs without damage (Yan et al4). EEC, enteroendocrine cell; LRC, label-retaining cell; PC, Paneth cell

These studies all rely on lineage tracing methods that are dependent on promoter-Cre constructs specific for non–stem cells, such as Alpi for absorptive cells and progenitors, and Mist1 (Bhlha15) for secretory cells and their progenitors. The existence of minor stem cell populations that activate and express these genes during damage can confuse the interpretation of subsequent lineage tracing results. In this context, Jones et al8 evaluated Lgr5 positivity in Defa4-marked cells and saw only extremely rare co-labeling, supporting the conclusion that Paneth cells specifically initiate lineage tracing and retain plasticity to generate stem cell populations after severe injury.

Together these studies suggest that several safety nets exist in the intestinal epithelium. From the perspective of the Waddington10 landscape, which models cellular differentiation as a ball rolling down a potential energy landscape, dedifferentiation occurs in cell types that require the least amount of energy to travel uphill to assume a Lgr5+ CBC identity. More specifically, we speculate on 2 factors that may modulate cellular plasticity in response to various damage stimuli. First, the differentiation status of a cell may limit the ability of a cell to dedifferentiate. The reversibility of a cellular state depends on the configuration of the chromatin landscape. Studies have shown that the chromatin landscapes between absorptive and secretory progenitors in the gut are similar to that of intestinal stem cells, while differentiated cells have markedly different landscapes.11, 12 These cells may have traveled too far down the Waddington landscape, with a locked-in chromatin configuration that can be reversed only by mobilization of pioneer transcription factors. Second and related, the plasticity response to damage may depend on the proliferation state of the cell. During mitosis, large portions of the chromatin landscape become accessible, allowing for reconfiguration to other states. In this regard, it should be noted that differentiated cells in the intestinal epithelium are nonproliferative, and they do not have access to this mechanism for resetting their landscapes. In the study by Jones et al8 featured in this issue, as well as recent work from Yu et al7 and Hayakawa et al,9 Notch activation is a universal mechanism of reverting Paneth cells into stem cells. Notch signaling in the intestinal epithelium triggers proliferative stem cell activity and is known to direct cells toward the absorptive lineage. These absorptive progenitors have a multifold increased proliferation rate compared with secretory progenitors. Thus, it follows that upon DT-mediated Lgr5+ cell ablation, lineage tracing is observed only from enterocyte progenitors among non–stem cells, as enterocyte progenitors have the most plastic landscapes.5

Together, all of these studies suggest that the intestinal epithelium has developed multiple mechanisms to regenerate the epithelium through both activation of resident stem cell populations as well as mobilization of plasticity within differentiated cell populations to generate reparative stem cell populations. We suggest that a hierarchical organization of cellular dedifferentiation exists in the intestinal epithelium. In response to varying degrees of damages, distinct cell populations are preferentially mobilized depending on their differentiation and proliferative status. It also remains possible, especially in the context of chronic injury, as in Crohn’s disease, that metaplastic lineages may play a critical role in abrogating severe epithelial damage in preparation for stem cell regeneration of a normal epithelium. All of these mechanisms provide a broad repertoire of overlapping mucosal repair mechanisms that can be mobilized based on the severity and chronicity of injury.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors disclose no conflicts.

Contributor Information

Ken S. Lau, Email: ken.s.lau@vanderbilt.edu.

James R. Goldenring, Email: jim.goldenring@vanderbilt.edu.

References

- 1.Cheng H., Leblond C.P. Origin, differentiation and renewal of the four main epithelial cell types in the mouse small intestine V. Unitarian theory of the origin of the four epithelial cell types. Am J Anat. 1974;141:537–561. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001410407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Potten C.S. Stem cells in gastrointestinal epithelium: numbers, characteristics and death. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 1998;353:821–830. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1998.0246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Es J.H., Sato T., Van De Wetering M., Lyubimova A., Nee A.N.Y., Gregorieff A., Martens A.C. Dll1+ secretory progenitor cells revert to stem cells upon crypt damage. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:1099. doi: 10.1038/ncb2581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buczacki S.J., Zecchini H.I., Nicholson A.M., Russell R., Vermeulen L., Kemp R., Winton D.J. Intestinal label-retaining cells are secretory precursors expressing Lgr5. Nature. 2013;495:65. doi: 10.1038/nature11965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tetteh P.W., Basak O., Farin H.F., Wiebrands K., Kretzschmar K., Begthel H., Van Oudenaarden A. Replacement of lost Lgr5-positive stem cells through plasticity of their enterocyte-lineage daughters. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;18:203–213. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yan K.S., Gevaert O., Zheng G.X., Anchang B., Probert C.S., Larkin K.A., Roelf K. Intestinal enteroendocrine lineage cells possess homeostatic and injury-inducible stem cell activity. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;21:78–90. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2017.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu S., Tong K., Zhao Y., Balasubramanian I., Yap G.S., Ferraris R.P., Gao N. Paneth cell multipotency induced by notch activation following injury. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;23:46–59.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones J.C., Brindley C.D., Elder N.H., Myers M.G., Jr., Rajala M.W., Dekaney C.M., McNamee E.N., Frey M.R., Shroyer N.F., Dempsey P.J. Cellular plasticity of Defa4Cre-expressing Paneth cells in response to notch activation and intestinal injury. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;7:533–554. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2018.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayakawa Y., Tsuboi M., Asfaha S., Kinoshita H., Niikura R., Konishi M., Hikiba Y. BHLHA15-positive secretory precursor cells can give rise to tumors in intestine and colon in mice. Gastroenterology. 2018 Nov 15 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waddington CH. The Strategy of the Genes, a Discussion of Some Aspects of Theoretical Biology. Abingdon: Routledge; 1957.

- 11.Jadhav U., Saxena M., O’Neill N.K., Saadatpour A., Yuan G.C., Herbert Z., Shivdasani R.A. Dynamic reorganization of chromatin accessibility signatures during dedifferentiation of secretory precursors into Lgr5+ intestinal stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;21:65–77. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2017.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim T.H., Li F., Ferreiro-Neira I., Ho L.L., Luyten A., Nalapareddy K., Shivdasani R.A. Broadly permissive intestinal chromatin underlies lateral inhibition and cell plasticity. Nature. 2014;506:511. doi: 10.1038/nature12903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]